Peer-Assisted Learning for First-Year Nursing Student Success and Retention: Findings from a Regional Australian Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. First-Year Participants

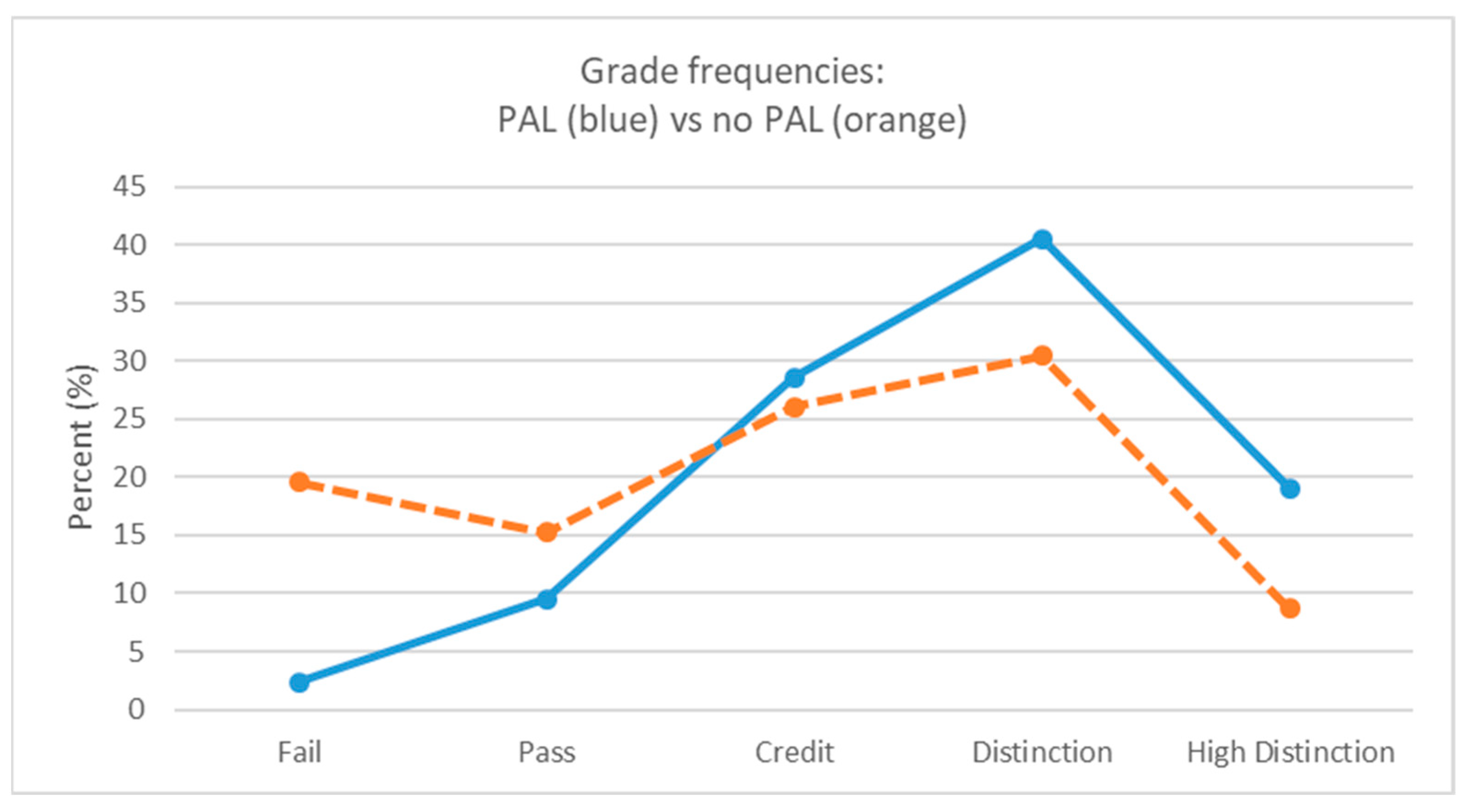

3.1.1. First Year BN Attrition and Retention Data

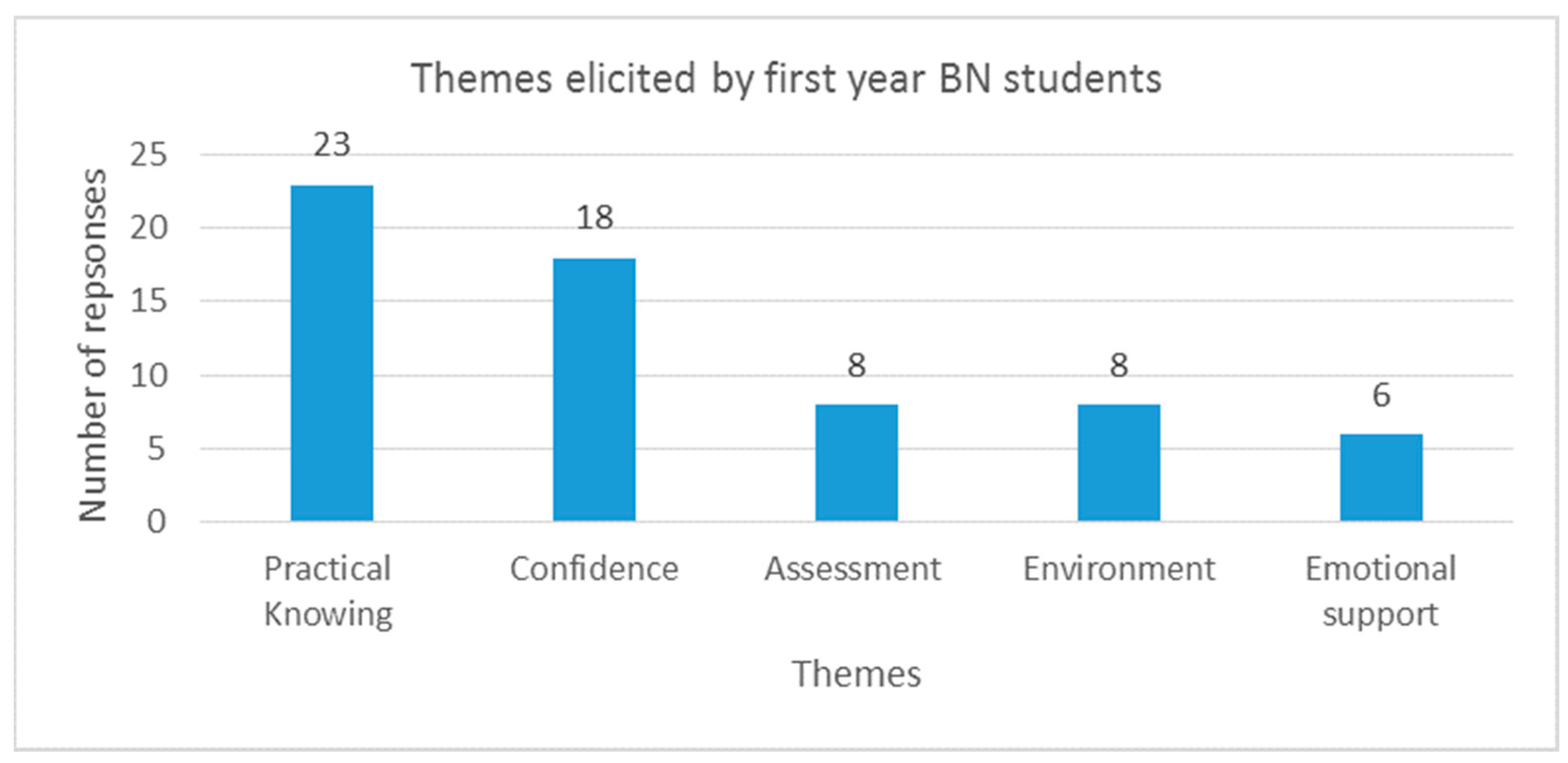

3.1.2. First-Year Qualitative Responses

Practical Knowing

PAL sessions were absolutely beneficial to my learning. Having an opportunity to go over skills learnt in class and being guided by third-year students definitely helped me to refine skills learnt and to turn theory into practical knowledge and skills. Knowing third-year students had learnt these skills & passed the same assessments less than 2 years ago was very encouraging in the “if they can do it” sense.

Confidence

Extremely beneficial to my learning as I could book into numerous PAL sessions and practice until I was confident.

Helped me feel more confident in my assessments.

Gave me confidence and knowledge that impacted my ability to get a good grade by empowering me to practice and learn more.

Confidence in my skills that others had done it with added “life pressure” like myself and succeeded.

Assessment

It allowed us to work on our scenarios, which overall helped when the assessments were on.

Helped me to feel more confident in my assessments for when I go on my professional experience placement.

Environment and Emotional Support

Made me feel a part of the student nurse community.

Third-year students were supportive.

Talking to third years also allowed us to see what it would be like if we continued in our studies.

Third-year students were encouraging & excited about the course which promoted drive to study and positivity around a career in nursing.

Showed me what my pathway looked like.

Third-year students I encountered were exceptional in their communication and instruction. Observing them speak & conduct themselves like qualified nurses made me realise that over the course of time the 3rd years had gained all the skills needed to communicate like a professional and complete clinical tasks with competence, even though they too struggled at the beginning. This in itself was a huge boost of encouragement and confidence.

3.2. Third-Year Student LabPALs

3.2.1. LabPAL Qualitative Responses

Professional Development

I thought the project was really beneficial—it helped me cement my own knowledge and made me realise how far I’d come in terms of my own clinical knowledge and experience… It made me wish that I’d had a similar thing happening when I was a first-year student.

As a third-year student the program provided me with a unique opportunity to develop my skills as a clinician and provided me with a competitive edge for graduate employment.

Confidence

I now have confidence in myself that I am able to help future nurses develop their skills and knowledge.

I believe this experience has given me the confidence to take on a preceptor role in the future.

This program has given me more confidence to work alone without support.

Mentoring

This program has reminded me of a number of things regarding nursing and mentoring. To me this closely involves culture and having an attitude that is gentle but sure and as least intimidating as possible.

I found it challenging at times to remember that you are not their teacher, but more of a guide to point them in the right direction.

Learning Philosophy

It also reinforced that as adults, we learn differently and at different rates.

The new students find the answers with their own reasoning.

I did find the role beneficial to my own learning as it highlighted that to effectively guide a learning experience, as the guide, you had to adapt a variety of communication styles that conveyed the message or experience that you were sharing with the student.

Leadership Skills

The leadership unit that ran this session aligned very well with the project as I was able to practice leadership styles I was learning.

The program allowed me to enhance and develop my leadership skills in a comfortable yet professional environment.

Transformational leadership as a key element reminded me to be inspirational, positive and encouraging.

More than one person assisting is needed as it was difficult to give everyone attention

I would have preferred it to not have clashed with a fairly intense semester.

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PAL | Peer-assisted learning |

| LabPAL | Laboratory-based PAL |

| PASS | Peer-assisted study sessions |

| SES | Socio-economic status |

References

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, L.; Williams, B. The hidden curriculum in near-peer learning: An exploratory qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 50, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Meer, J.; Scott, C. Students’ Experiences and Perceptions of Peer Assisted Study Sessions: Towards Ongoing Improvement. Australasian. J. Peer Learn. 2009, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2024; United Nations: New York City, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild, A.; Butler, C. Building the foundations for academic success: Learning from the experiences of part-time students in their first semester of study. Widening Particip. Lifelong Learn. 2020, 22, 135–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, R.; Swanson, V.; Watkins, R. The impact of peer mentoring on levels of student wellbeing, integration and retention: A controlled comparative evaluation of residential students in UK higher education. High. Educ. 2014, 68, 927–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NMBA. Registered Nurse Standards for Practice; Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- NMBA. Code of Conduct for Nurses; Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia: Melbourne, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Health Workforce Australia Health. In Workforce 2025. Doctors, Nurses and Midwives; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2012; Volume 1. Available online: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2021/03/nurses-australia-s-future-health-workforce-reports-detailed-report.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Schwartz, S. Educating the Nurse of the Future; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, M.; Jolly, R. The Crisis in the Caring Workforce; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2024. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/about_parliament/parliamentary_departments/parliamentary_library/pubs/briefingbook44p/caringworkforce (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Tower, M.; Walker, R.; Wilson, K.; Watson, B.; Tronoff, G. Engaging, supporting and retaining academic at-risk students in a Bachelor of Nursing: Setting risk markers, interventions and outcomes. Stud. Success 2015, 6, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sheikoleslami, R.L.; Princeton, D.M.; Mihaila Hansen, L.I.; Kisa, S.; Goyal, A.R. Examining Factors Associated with Attrition, Strategies for Retention Among Undergraduate Nursing Students, and Identified Research Gaps: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Z.C.Y.; Cheng, W.Y.; Fong, M.K.; Fung, Y.S.; Ki, Y.M.; Li, Y.L.; Wong, H.T.; Wong, T.L.; Tsoi, W.F. Curriculum design and attrition among undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 74, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, A.; Hunt, L.; Lord, H.; Halcomb, E.; Fernandez, R.; Middleton, R.; Moxham, L. Understanding the support needs of Australian nursing students during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Contemp. Nurse: J. Aust. Nurs. Prof. 2021, 57, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-L.; Wang, T.; Bressington, D.; Nic Giolla Easpaig, B.; Wikander, L.; Tan, J.-Y. Factors Influencing Retention among Regional, Rural and Remote Undergraduate Nursing Students in Australia: A Systematic Review of Current Research Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, M.; Chapman, Y.; Ralph, N.; McPherson, C.; Eliot, M.; Coyle, M. Undergraduate nursing studies: The first-year experience. J. Institutional Res. 2013, 18, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, L. ‘Go boldly, dream large!’: The challenges confronting non-traditional students at university. Aust. J. Educ. 2011, 55, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N.A.; Preschel, S.; Martinez, D. Does Supplemental Instruction Improve Grades and Retention? A Propensity Score Analysis Approach. J. Exp. Educ. 2023, 91, 205–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambas, S.I.; Dutch, S.; Gerrard, D. Factors influencing Māori student nurse retention and success: An integrative literature review. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 91, 104477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, C.; Ellis, L.; Reid, E.R. Peer-assisted learning in medical education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2022, 56, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Reddy, P. Does peer-assisted learning improve academic performance? A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 42, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, M.; Stewart, L.; Ferguson, L. Peer learning partnership: An innovative strategy to enhance skill acquisition in nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2006, 26, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.P.; Gainey, K.L.; Kershner, S.H.; Weaver, D.L.; Hucks, J.M. Junior and Senior Nursing Students: A Near-Peer Simulation Experience. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 59, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.Y.; Kim, B.Y. Differences in The Effects of Core Nursing Skills Education According to the Use of Peer-Assisted Learning (PAL) Among Nursing Students. Int. J. Contents 2019, 15, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hamarash, M.Q.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Yaas, M.H.; Almushhadany, O.I.; Al Mukhtar, S.H. Using Peer-Assisted Learning to Enhance Clinical Reasoning Skills in Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Study in Iraq. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2025, 16, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, S.; D’Amore, A.; Thomas, T. Learning preferences of first year nursing and midwifery students: Utilising VARK. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldseid, C.; Friberg, F.; Aase, K. Nursing students’ perceptions of factors influencing their learning environment in a clinical skills laboratory: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2015, 35, e1–e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.; Markauskaite, L. Examining the role of authenticity in supporting the development of professional identity: An example from teacher education. High. Educ. 2012, 64, 747–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smedley, A.; Morey, P. Improving learning in the clinical nursing environment: Perceptions of senior Australian bachelor of nursing students. J. Res. Nurs. 2010, 15, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, A.; Bell, A. Peer learning partnerships: Exploring the experience of pre-registration nursing students. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, S.; Williams, B.; McKenna, L. Near-peer teaching in undergraduate nurse education: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 70, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brannagan, K.B.; Dellinger, A.; Thomas, J.; Mitchell, D.; Lewis-Trabeaux, S.; Dupre, S. Impact of peer teaching on nursing students: Perceptions of learning environment, self-efficacy, and knowledge. Nurse Educ. Today 2013, 33, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flott, E.; Ball, S.; Hanks, J.; Minnich, M.; Kirkpatrick, A.; Rusch, L.; Koziol, D.; Laughlin, A.; Williams, J. Fostering collaborative learning and leadership through near-peer mentorship among undergraduate nursing students. Nurs. Forum 2022, 57, 750–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, A.J.T.Y.; Chow, F.L.W. Learning partnership—The experience of peer tutoring among nursing students: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegram, A.; Fordham-Clarke, C. Implementing peer learning to prepare students for OSCEs. Br. J. Nurs. 2015, 24, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenau, P.A.; Lisella, R.F.; Clancy, T.L.; Nowell, L.S. Developing future nurse educators through peer mentoring. Nurs. Res. Rev. 2015, 2015, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Beattie, M.; Kyle, R.G. Stepping up, stepping back, stepping forward: Student nurses’ experiences as peer mentors in a pre-nursing scholarship. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2015, 15, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfadenhauer, M.; Knoblauch, H. Social Constructivism as Paradigm? The Legacy of the Social Construction of Reality; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. Focus on research methods. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V.; Hayfield, N.; Terry, G. Thematic analysis. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The Use of Triangulation in Qualitative Research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.T.; Allen, T.D.; Evans, S.C.; Ng, T.; DuBois, D.L. Does mentoring matter? A multidisciplinary meta-analysis comparing mentored and non-mentored individuals. J. Vocat. Behav. 2008, 72, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, S. Peer mentoring: Untapped potential. J. Nurs. Educ. 2010, 49, 340–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.; Cooper, S.; Cant, R.; Funnell, M.M.; Beebe, L.H. The Value of Peer Learning in Undergraduate Nursing Education: A Systematic Review. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelwati Abdullah, K.L.; Chan, C.M. A systematic review of qualitative studies exploring peer learning experiences of undergraduate nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 71, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, B. The zone of proximal development as an overarching concept: A framework for synthesizing Vygotsky’s theories. Educ. Philos. Theory 2019, 51, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edge, D.; Gladstone, N. Exploring support strategies for improving nursing student retention. Nurs. Stand. 2022, 37, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.-L.; Nic Giolla Easpaig, B.; Garti, I.; Bressington, D.; Wang, T.; Wikander, L.; Tan, J.Y. Improving success and retention of undergraduate nursing students from rural and remote Australia: A multimethod study protocol. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2024, 75, 103876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynter, K.; Redley, B.; Holton, S.; Manias, E.; McDonall, J.; McTier, L.; Hutchinson, A.M.; Kerr, D.; Lowe, G.; Phillips, N.N.; et al. Depression, anxiety and stress among Australian nursing and midwifery undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Educ. Scholarsh. 2021, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewertsson, M.; Allvin, R.; Holmström, I.K.; Blomberg, K. Walking the bridge: Nursing students’ learning in clinical skill laboratories. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2015, 15, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P.; Sutphen, M.; Leonard, V.; Day, L. Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, B.R.; Drenkard, K.; Esposito-Herr, M.B.; Romano, C.; Tom, S.; Valentine, N. Educating nurses for leadership roles. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2004, 35, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) 1 | 17–20 | 6 | 23 |

| 21–25 | 7 | 27 | |

| 26–35 | 7 | 27 | |

| 36–45 | 4 | 15 | |

| >45 | 2 | 8 | |

| First in family | 14 | 52 | |

| Low SES background 2 | 8 | 30 | |

| Previous PAL | PASS | 3 | 11 |

| Other 3 | 5 | 18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Woods, A.; Lotherington, F.; Steffensen, P.; Theophilos, T. Peer-Assisted Learning for First-Year Nursing Student Success and Retention: Findings from a Regional Australian Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070252

Woods A, Lotherington F, Steffensen P, Theophilos T. Peer-Assisted Learning for First-Year Nursing Student Success and Retention: Findings from a Regional Australian Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):252. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070252

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoods, Andrew, Fiona Lotherington, Paula Steffensen, and Theane Theophilos. 2025. "Peer-Assisted Learning for First-Year Nursing Student Success and Retention: Findings from a Regional Australian Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070252

APA StyleWoods, A., Lotherington, F., Steffensen, P., & Theophilos, T. (2025). Peer-Assisted Learning for First-Year Nursing Student Success and Retention: Findings from a Regional Australian Study. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 252. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070252