Factors Affecting Long-Term Outcomes for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Cross-Sectional Design

Abstract

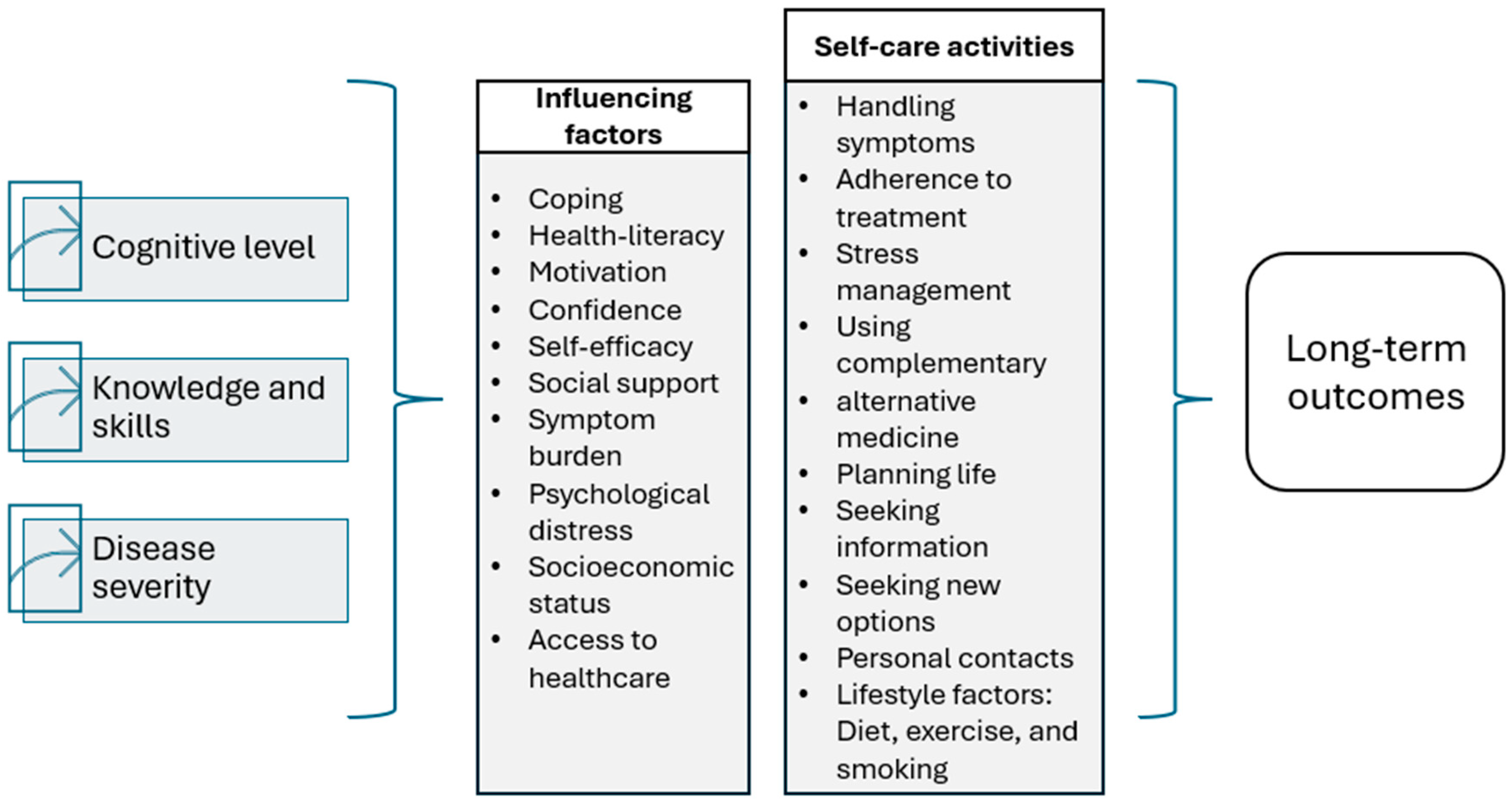

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sample and Setting

2.3. Data Collection and Measurement

2.3.1. The Brief Cope

2.3.2. Social Support

2.3.3. The Short Health Scale

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Social Support

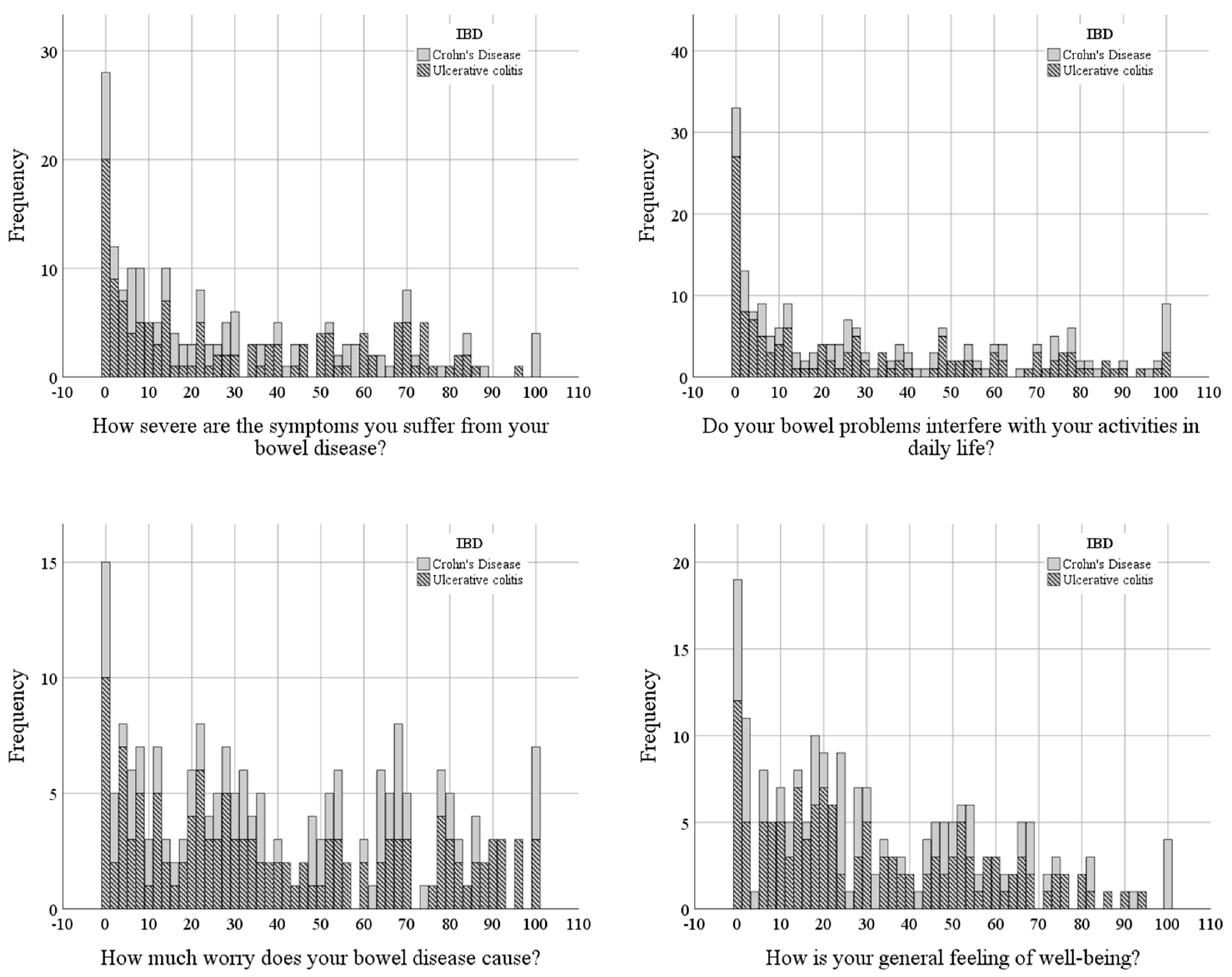

3.3. Health-Related Quality of Life

3.4. Coping Strategies Among Patients with IBD

3.5. Associations Between Patient Characteristics, Coping, Social Support, and Health-Related Quality of Life

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Clinical Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

| UC | Ulcerative Colitis |

| CD | Crohn´s Disease |

References

- Alatab, S.; Sepanlou, S.G.; Ikuta, K.; Vahedi, H.; Bisignano, C.; Safiri, S.; Sadeghi, A.; Nixon, M.R.; Abdoli, A.; Abolhassani, H.; et al. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, C.; Vadhariya, A.; Bires, N.; Brady, B.; Creveling, T.; Evans, K.; Panni, T.; Chan-Diehl, F.W.; McGinnis, K. Real-World Dosing Patterns of Biologics in Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis: A Retrospective Observational Study. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2025, 31, S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, K.; Dudley-Brown, S.; Heitkemper, M.; Wyatt, G.; Given, B. Symptoms among emerging adults with inflammatory bowel disease: A descriptive study. Res. Nurs. Health 2020, 43, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eugenicos, M.P.; Ferreira, N.B. Psychological factors associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 138, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, D.; McCarthy, G.; Savage, E. Self-reported Symptom Burden in Individuals with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Saikam, V.; Skrada, K.A.; Merlin, D.; Iyer, S.S. Inflammatory bowel disease biomarkers. Med. Res. Rev. 2022, 42, 1856–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, S.; Jackson, D.; Aveyard, H. Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A review of qualitative research studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 87, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapwong, P.; Norton, C.; Rowland, E.; Farah, N.; Czuber-Dochan, W. A systematic review of the impact of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on family members. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 2228–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Strömberg, A. A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2012, 35, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Dunbar, S.B.; Fitzsimons, D.; Freedland, K.E.; Lee, C.S.; Middleton, S.; Stromberg, A.; Vellone, E.; Webber, D.E.; Jaarsma, T. Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 116, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; DiClemente, C.C.; Norcross, J.C. In search of how people change. Applications to addictive behaviors. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovén Wickman, U.; Yngman-Uhlin, P.; Hjortswang, H.; Riegel, B.; Stjernman, H.; Hollman Frisman, G. Self-Care Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Interview Study. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 2016, 39, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, D.; Vellone, E.; Iovino, P.; Scaldaferri, F.; Cocchieri, A. Self-care in patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease and caregiver contribution to self-care (IBD-SELF): A protocol for a longitudinal observational study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2024, 11, e001510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, J.L.; Greene-Higgs, L.; Swanson, L.; Higgins, P.D.R.; Krein, S.L.; Waljee, A.K.; Saini, S.D.; Berinstein, J.A.; Mellinger, J.L.; Piette, J.D.; et al. Self-Efficacy and the Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Patients’ Daily Lives. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, J.L.; Greene-Higgs, L.; Resnicow, K.; Patel, M.R.; Barnes, E.L.; Waljee, A.K.; Higgins, P.D.R.; Cohen-Mekelburg, S. Self-Efficacy, Patient Activation, and the Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Patients’ Daily Lives. Dig Dis Sci. 2024, 69, 4089–4097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keil, R.M. Coping and stress: A conceptual analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 45, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ta, N.; Yi, S.; Xiong, H. Intolerance of uncertainty and mental health in patients with IBD: The mediating role of maladaptive coping. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Popa, S.L.; Fadgyas Stanculete, M.; Grad, S.; Brata, V.D.; Duse, T.A.; Badulescu, A.V.; Dragan, R.V.; Bottalico, P.; Pop, C.; Ismaiel, A.; et al. Coping Strategies and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Narrative Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarchuck, O.; Balakhtar, V.; Pinchuk, N.; Pustovalov, I.; Pavlenok, K. Coping with stressfull situations using coping strategies and their impact on mental health. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 7, 2024spe2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene-Higgs, L.; Jordan, A.; Sheehan, J.; Berinstein, J.; Admon, A.J.; Waljee, A.K.; Riehl, M.; Piette, J.; Resnicow, K.; Higgins, P.D.; et al. Social Network Diversity and the Daily Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2023, 14, e00572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urstad, K.H.; Andersen, M.H.; Larsen, M.H.; Borge, C.R.; Helseth, S.; Wahl, A.K. Definitions and measurement of health literacy in health and medicine research: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovén Wickman, U.; Ågren, S. Health Literacy: A Pathway to Better Health for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease-An Integrative Literature Review. Int. J. Nurs. Health Care Res. 2025, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velonias, G.; Conway, G.; Andrews, E.; Garber, J.J.; Khalili, H.; Yajnik, V.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Older Age- and Health-related Quality of Life in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min Ho, P.Y.; Hu, W.; Lee, Y.Y.; Gao, C.; Tan, Y.Z.; Cheen, H.H.; Wee, H.L.; Lim, T.G.; Ong, W.C. Health-related quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Singapore. Intest. Res. 2019, 17, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, D. The WHO Definition of “Health”, The Roots of Bioethics: Health, Progress, Technology, Death; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, F. The Definition of Health: Towards New Perspectives. Int. J. Health Serv. 2018, 48, 735–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W. Definitions of quality of life: What has happened and how to move on. Top. Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2014, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Sebastian, S.A.; Parmar, M.P.; Ghadge, N.; Padda, I.; Keshta, A.S.; Minhaz, N.; Patel, A. Factors influencing the quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease: A comprehensive review. Dis Mon. 2024, 70, 101672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- STROBE. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Carver, C.S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’ too long: Consider the brief cope. Int. J. Behav. Med. 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S.; Scheier, M.F.; Weintraub, J.K. Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. J. Personal. Social. Psychol. 1989, 56, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulus, D.; Coulter, T.J.; Trotter, M.G.; Polman, R. Stress and Coping in Esports and the Influence of Mental Toughness. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhonen, T.; Torkelson, E. Kortversioner av frågeformulär inom arbets- och hälsopsykologi. Nord. Psykol. Teor. Forsk. Praksis 2005, 57, 288–297. [Google Scholar]

- Undén, A.L.; Orth-Gomér, K. Development of a social support instrument for use in population surveys. Soc. Sci. Med. 1989, 29, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortswang, H.; Järnerot, G.; Curman, B.; Sandberg-Gertzén, H.; Tysk, C.; Blomberg, B.; Almer, S.; Ström, M. The Short Health Scale: A valid measure of subjective health in ulcerative colitis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 41, 1196–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenstock, I. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Education Monographs. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, B.; Jaarsma, T.; Lee, C.S.; Strömberg, A. Integrating Symptoms Into the Middle-Range Theory of Self-Care of Chronic Illness. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2019, 42, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCombie, A.M.; Mulder, R.T.; Gearry, R.B. How IBD patients cope with IBD: A systematic review. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2013, 7, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iizawa, M.; Hirose, L.; Nunotani, M.; Nakashoji, M.; Tairaka, A.; Fernandez, J.L. A Systematic Review of Self-Management Interventions for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Intest. Dis. 2023, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Manser, C.; Pittet, V.; Vavricka, S.R.; Biedermann, L. Gender Differences in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestion 2020, 101 (Suppl. 1), 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz González, E.; Durantez-Fernández, C.; Pérez-Pérez, L.; de Dios-Duarte, M.J. Influence of Coping and Self-Efficacy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Y.; Artan, Y.; Unal, N.G. Relationship Between Social Isolation, Loneliness and Psychological Well-Being in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: The Mediating Role of Disease Activity Social Isolation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severs, M.; Spekhorst, L.M.; Mangen, M.-J.J.; Dijkstra, G.; Löwenberg, M.; Hoentjen, F.; van der Meulen-de Jong, A.E.; Pierik, M.; Ponsioen, C.Y.; Bouma, G.; et al. Sex-Related Differences in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results of 2 Prospective Cohort Studies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2018, 24, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, G.G.; Ng, S.C. Understanding and Preventing the Global Increase of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2017, 152, 313–321.e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurud, S.; Lunde, L.; Moen, A.; Opheim, R. Mapping conditional health literacy and digital health literacy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease to optimise availability of digital health information: A cross-sectional study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 60, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.-J.; Zhao, K.; Fils-Aime, F. Response rates of online surveys in published research: A meta-analysis. Comput. Human. Behav. Rep. 2022, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| - Active coping, (Problem-Focused) - Use of informational support, (Problem-Focused) - Positive reframing, (Problem-Focused) - Planning, (Problem-Focused) - Emotional support, (Emotion-Focused) - Venting, (Emotion-Focused) - Humor, (Emotion-Focused) - Acceptance, (Emotion-Focused) - Religion, (Emotion-Focused) - Self-blame, (Emotion-Focused) - Self-distraction, (Avoidant) - Denial, (Avoidant) - Substance use, (Avoidant) - Behavioral disengagement, (Avoidant) |

| Variables | Response |

|---|---|

| No/yes, but I don’t need/yes |

| no/not sure/yes |

| no/yes |

| no/yes |

| no/yes |

| Yes, not enough, not at all |

| none/1–2/3–5/6–10/11–15/more than 15 |

| Variables | CD | UC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients, n (%) | 77 (37.4) | 129 (62.6) | 206 |

| Age, median (years/range) | 49 (19–87) | 48 (20–83) | 48 (19–87) |

| Time since diagnosis, median (years/range) | 14 (0–50) | 10 (0–50) | 12 (0–50) |

| Female/male ratio | 40:37 | 70:59 | 110:96 |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | 42 (54.5) | 13 (10) | 55 (27%) |

| Missing data age (n = 9), time since diagnosis (n = 4) | |||

| Items in Short Health Scale | CD | UC |

| How severe symptoms do you suffer from your bowel disease? | 23 (48) | 22 (39.5) |

| Does your bowel disease interfere with your activities in daily life? | 29 (58.2) | 19 (50.5) |

| How much worry does your bowel disease cause? | 36 (51.7) | 31.5 (54.5) |

| What is your general sense of well-being? | 28 (42.2) | 22.5 (41.2) |

| Item | M* | SD** | Md*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Item 2. I’ve been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I’m in. | 2.63 | 0.84 | 3.00 |

| Item 5. I’ve been getting emotional support from others. | 2.63 | 0.88 | 3.00 |

| Item 7 I’ve been taking action to try to make the situation better. | 2.76 | 0.87 | 3.00 |

| Item 12. I’ve been trying to see it in a different light, to make it seem more positive. | 2.42 | 0.82 | 2.00 |

| Item 14. I’ve been trying to come up with a strategy about what to do. | 2.78 | 0.86 | 3.00 |

| Item 15. I’ve been getting comfort and understanding from someone. | 2.62 | 0.84 | 2.00 |

| Item 17. I’ve been looking for something good in what is happening. | 2.63 | 0.82 | 3.00 |

| Item 23. I’ve been trying to get advice or help from other people about what to do. | 2.33 | 0.75 | 3.00 |

| Item 24. I’ve been learning to live with it. | 2.95 | 0.82 | 3.00 |

| Item 25. I’ve been thinking hard about what steps to take. | 2.62 | 0.86 | 3.00 |

| Coping Variables | Well-Being (Rho) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| I use alcohol or other drugs to feel better | 0.167 | 0.018 |

| I use alcohol or other drugs to help me get through it | 0.149 | 0.035 |

| I try to look at it in a different light to make it seem more positive | 0.188 | 0.008 |

| I try to come up with a strategy for what I should do | 0.192 | 0.009 |

| I joke about it | 0.152 | 0.033 |

| Negative emotions | 0.182 | 0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lovén Wickman, U. Factors Affecting Long-Term Outcomes for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Cross-Sectional Design. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070231

Lovén Wickman U. Factors Affecting Long-Term Outcomes for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Cross-Sectional Design. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070231

Chicago/Turabian StyleLovén Wickman, Ulrica. 2025. "Factors Affecting Long-Term Outcomes for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Cross-Sectional Design" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070231

APA StyleLovén Wickman, U. (2025). Factors Affecting Long-Term Outcomes for Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease—A Cross-Sectional Design. Nursing Reports, 15(7), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070231