Development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Web Application (Psychosocial Rehab App)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Theoretical Foundation of the Web App Psychosocial Rehab App

2.2. Prototyping Requirements Survey

2.3. Prototyping

2.4. Development with Alpha Testing

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

Narrative Summary of the Findings in Table 3

4. Discussion

4.1. Constructing and Improving the Instructional Design for the Development of the Psychosocial Rehab App

4.2. Exchange of Knowledge and Collaborative Work in the Construction of the Instructional Design and Development of the Psychosocial Rehab App

4.3. Development of the Psychosocial Rehab App with Testing and Feedback from the Lead Researcher

4.3.1. Use of the Psychosocial Rehab App

4.3.2. Potentialities, Future Directions, and Limitations of the Psychosocial Rehab App

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khademian, F.; Aslani, A.; Bastani, P. The effects of mobile apps on stress, anxiety, and depression: Overview of systematic reviews. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 2021, 37, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinengo, L.; Stona, A.C.; Griva, K.; Dazzan, P.; Pariante, C.M.; von Wangenheim, F.; Car, J. Self-guided Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Apps for Depression: Systematic Assessment of Features, Functionality, and Congruence with Evidence. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denecke, K.; Schmid, N.; Nüssli, S. Implementation of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in e–Mental Health Apps: Literature Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e27791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschitz, J.M.; Van Boxtel, R.; Torous, J.; Firth, J.; Lebovitz, J.G.; Burdick, K.E.; Hogan, T.P. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression: Scoping Review of User Engagement. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e39204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.P.; Barroso, B.; Deusdado, L.; Novo, A.; Guimarães, M.; Teixeira, J.P.; Leitão, P. Digital Technologies for Innovative Mental Health Rehabilitation. Electronics 2021, 10, 2260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, E.A.; Lyman, C.; Roberts, J.E. Development of an mHealth App–Based Intervention for Depressive Rumination (RuminAid): Mixed Methods Focus Group Evaluation. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e40045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.; da Silva, J.C.B.; de Almeida, J.M.; Feitosa, F.B. Reabilitação Psicossocial: O Relato de um Caso na Amazônia. Saúde Em Redes 2021, 7 (Suppl. S2), 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.; García, J.C.S.; Feitosa, F.B.; de Oliveira Reis, I.; Caritá, E.C.; Moll, M.F.; Ventura, C.A.A. Fundamentos teóricos e bioéticos para o desenvolvimento do aplicativo de projeto de reabilitação psicossocial. Saúde Redes 2025, 11, 4430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acebal, J.S.; Barbosa, G.C.; Domingos, T.D.S.; Bocchi, S.C.M.; Paiva, A.T.U. O habitar na reabilitação psicossocial: Análise entre dois Serviços Residenciais Terapêuticos. Saúde Debate 2020, 44, 1120–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.F.L.; Mendes, A.M.P. Reabilitação psicossocial e cidadania: O trabalho e a geração de renda no contexto da oficina de panificação do Caps Grão-Pará. Cad. Bras. Saúde Ment. 2020, 12, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- de Melo Zubiaurre, P.; Wasum, F.D.; Tisott, Z.L.; de Andrade, T.M.M.D.; de Oliveira, M.A.F.; de Siqueira, D.F. O desenvolvimento do projeto terapêutico singular na saúde mental: Revisão integrativa. Arq. Ciênc. Da Saúde Da UNIPAR 2023, 27, 2788–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.M.C. Reabilitação psicossocial no campo da reforma psiquiátrica: Uma reflexão sobre o controverso conceito e seus possíveis paradigmas. Rev. Latinoam. Psicopatol. Fundam. 2004, 7, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.; García, J.C.S.; Feitosa, F.B.; Moll, M.F.; Rodriguez, T.D.M.; Ventura, C.A.A. Construction and validation of the content and appearance of the application prototype of a Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project. Enferm. Glob. 2025, 24, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, I.C.S.; de Galiza, D.D.F.; Júnior, A.R.F.; Cavalcante, A.S.P.; do Nascimento, C.E.M.; Sampaio, J.J.C. Produção de práticas de saúde mental integradas em rede de atenção à saúde. Diálogos Interdiscip. Em Psiquiatr. Saúde Ment. 2023, 2, e10863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Martinengo, L.; Jabir, A.I.; Ho, A.H.Y.; Car, J.; Atun, R.; Car, L.T. Scope, Characteristics, Behavior Change Techniques, and Quality of Conversational Agents for Mental Health and Well-Being: Systematic Assessment of Apps. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e45984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, E.A.d.A.C.; Ferreira, A.A.; Bezerra, S.A.C.; da Cruz Portela, L.; Júnior, S.A.C.B. Desenvolvimento de um protótipo móvel para auxiliar enfermeiros: Diagnóstico de enfermagem em saúde mental. Rev. Contemp. 2023, 3, 11228–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrell, L.; Furneaux-Bate, A.; Debenham, J.; Spallek, S.; Newton, N.; Chapman, C. Development of a Peer Support Mobile App and Web-Based Lesson for Adolescent Mental Health (Mind Your Mate): User-Centered Design Approach. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e36068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, J.A.; Jacob, J.D.; Siegle, G.J.; Dey, A.; Thase, M.E.; Dabbs, A.D.; Kazantzis, N.; Rotondi, A.; Tamres, L.; Van Slyke, A.; et al. CBT MobileWork: User-Centered Development and Testing of a Mobile Mental Health Application for Depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2021, 45, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, L.P.C.; dos Reis, P.L.C.; Casarin, R.G.; Caritá, E.; Silva, S.S. Desenvolvimento de aplicativo móvel como estratégia de educação para o matriciamento em saúde mental. Debates Em Educ. Cient. Tecnol. 2023, 13, 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel, P.; Karmacharya, R.; Salisbury, T.T.; Carswell, K.; Kohrt, B.A.; Jordans, M.J.D.; Lempp, H.; Thornicroft, G.; Luitel, N.P. Perception of healthcare workers on mobile app-based clinical guideline for the detection and treatment of mental health problems in primary care: A qualitative study in Nepal. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armando Cobo Campo, L.; Ignacio Pérez-Uribe, R. Proyecto Anamnesis-Desarrollo de una aplicación web y móvil para la gestión de una Historia Clínica Unificada de los colombianos. Revista EAN 2016, 80, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sturm, R.; Pollard, C.; Craig, J. Managing Web-Based Applications. In Application Performance Management (APM) in the Digital Enterprise; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 83–93. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, L.S.; Oliveira, E.N.; Vasconcelos, M.I.O.; Fernandes, C.A.R.; Dutra, M.C.X.; de Almeida, P.C. Desenvolvimento e validação de um jogo educativo sobre uso abusivo de drogas e o risco de suicídio. SMAD Rev. Eletrônica Saúde Ment. Álcool E Drog. (Edição Em Port.) 2023, 19, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, R.A.S. Desenvolvimento de Protótipo de Tecnologia Digital para Apoio aos Profissionais de Enfermagem Frente ao Estresse Ocupacional: Proposta de Intervenção. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Quinderé, P.H.D.; Jorge, M.S.B.; Franco, T.B. Rede de Atenção Psicossocial: Qual o lugar da saúde mental? Physis Rev. De Saúde Coletiva 2014, 24, 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagan, S.; Emerson, M.R.; King, D.; Matwin, S.; Chan, S.R.; Proctor, S.; Tartaglia, J.; Fortuna, K.L.; Aquino, P.; Walker, R.; et al. Mental Health App Evaluation: Updating the American Psychiatric Association’s Framework Through a Stakeholder-Engaged Workshop. Psychiatr. Serv. 2021, 72, 1095–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, N.; Greely, H.T.; Cho, M.K. Ethical development of digital phenotyping tools for mental health applications: Delphi study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2021, 9, e27343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, D.M.; Peixoto Junior, C.A. Clínica em movimento: A cidade como cenário do acompanhamento terapêutico. Fractal 2019, 31, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huckvale, K.; Nicholas, J.; Torous, J.; Larsen, M.E. Smartphone apps for the treatment of mental health conditions: Status and considerations. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 36, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, N.E.; Armstrong, C.M.; Hoyt, T.V. Smartphone apps for psychological health: A brief state of the science review. Psychol. Serv. 2019, 16, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.G.F.; da Rocha, D.J.L.; Melo, G.A.A.; Jaques, R.M.P.L.; Formiga, L.M.F. Building and validating a digital application for the teaching of surgical instrumentation. Cogitare Enferm. 2019, 24, e58334. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, D.F.; Carmona, E.V.; de Moraes Lopes, M.H.B. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the System Usability Scale to Brazilian Portuguese. Aquichan 2022, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, M.; José, O. Usabilidade da Interface de Dispositivos Móveis: Heurísticas e Diretrizes para o Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kruzan, K.P.; Reddy, M.; Washburn, J.J.; Mohr, D.C. Developing a Mobile App for Young Adults with Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: A Prototype Feedback Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 16163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemon, C.; Huckvale, K.; Carswell, K.; Torous, J. A Narrative Review of Methods for Applying User Experience in the Design and Assessment of Mental Health Smartphone Interventions. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 2020, 36, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordgreen, T.; Rabbi, F.; Torresen, J.; Skar, Y.S.; Guribye, F.; Inal, Y.; Flobakk, E.; Wake, J.D.; Mukhiya, S.K.; Aminifar, A.; et al. Challenges and possible solutions in cross-disciplinary and cross-sectoral research teams within the domain of e-mental health. J. Enabling Technol. 2021, 15, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.; Ponting, C.; Labao, J.P.; Sobowale, K. Considerations of diversity, equity, and inclusion in mental health apps: A scoping review of evaluation frameworks. Behav. Res. Ther. 2021, 147, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.A.A.C.; García, J.C.S.; Feitosa, F.B.M.; Caritá, E.C.; Ventura, C.A.A. Requisitos para a criação de um prototipo da webapp “App Projeto de Reabilitação Psicossocial”: Estudo de grupo focal. Rev. Port. Enferm. Saúde Ment. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Alfredo Ardisson Cirino Campos, F.; Feitosa, F.B.; Moll, M.F.; Reis, I.d.O.; Sánchez García, J.C.; Ventura, C.A.A. Initial Requirements for the Prototyping of an App for a Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, S.; Boudhraâ, S.; Dumont, M.; Tremblay, M.; Riendeau, S. Developing A Mobile App with a Human-Centered Design Lens to Improve Access to Mental Health Care (Mentallys Project): Protocol for an Initial Co-Design Process. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2023, 12, e47220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, K. As Percepções de Estudantes Universitários com Deficiência Visual Sobre a Acessibilidade aos Materiais Acadêmicos e as Repercussões Desse Acesso Sobre suas Trajetórias Acadêmicas; UNISUL: Santa Catarina, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klüber, T.E. Atlas/t.i como instrumento de análise em pesquisa qualitativa de abordagem fenomenológica. ETD—Educ. Temát. Digit. 2014, 16, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romualdo, J.F. Formação do Médico de Família e Comunidade no Contexto da Pandemia da COVID-19. Specialization Dissertation, Unifesp, São Paulo, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. Int. J. Transgend. Health. 2023, 24, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karine De Souza, L. Pesquisa com análise qualitativa de dados: Conhecendo a Análise Temática. Arq. Bras. Psicol. 2019, 71, 51–67. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, M.A.D.S.; Silva, M.R.D.; Nunes, M.S.C. Pesquisa qualitativa no campo estudos organizacionais: Explorando a análise temática. In Encontro da Associação Nacional de Pós—Graduação e Pesquisa em Administração; Universidade Federal de Sergipe: São Paulo, Brazil, 2017; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- da Rosa, L.S.; Mackedanz, L.F. Análise temática como metodologia na pesquisa qualitativa em educação em ciências. Atos De Pesqui. Em Educ. 2021, 16, e8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, M.R.; Barbosa, M.A.d. S, Lima, L.G.B. Usos e possibilidades metodológicas para os estudos qualitativos em Administração: Explorando a análise temática. Rev. Pensamento Contemp. Em Adm. 2020, 14, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, M.M.; Firth, J.; Minen, M.; Torous, J. User engagement in mental health apps: A review of measurement, reporting, and validity. Psychiatr. Serv. 2019, 70, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, H.; Jo, M.; Lee, C.; Kim, D. Development and Evaluation: A Behavioral Activation Mobile Application for Self-Management of Stress for College Students. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burn, A.M.; Ford, T.J.; Stochl, J.; Jones, P.B.; Perez, J.; Anderson, J.K. Developing a Web-Based App to Assess Mental Health Difficulties in Secondary School Pupils: Qualitative User-Centered Design Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2022, 6, e30565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, A.; Karver, T.S.; Roundfield, K.D.; Woodruff, S.; Wierzba, C.; Wolny, J.; Kaufman, M.R. The Appa Health App for Youth Mental Health: Development and Usability Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e49998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushniruk, A.W.; Turner, P. Who’s users? Participation and empowerment in socio-technical approaches to health IT developments. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M.; Aarts, J.; Van Der Lei, J. ICT in Health Care: Sociotechnical Approaches. Methods Inf. Med. 2003, 42, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.C. Aconchego: Construção e Validação de Aplicativo para Apoio à Saúde Mental. Master’s Dissertation, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Torous, J.; Roberts, L.W. The Ethical Use of Mobile Health Technology in Clinical Psychiatry. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017, 205, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Queiroz, G. Second Mind: Considerações Ético-Legais sobre a Digitalização em Saúde Mental no Contexto Português. Rev. Port. De Psiquiatr. E Saúde Ment. 2022, 8, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Honey, M.L.L. User perceptions of mobile digital apps for mental health: Acceptability and usability—An integrative review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.R.; Ribeiro, A.L.P. Revisão sistemática e meta-análise de estudos de diagnóstico e prognóstico: Um tutorial. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2009, 92, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakob, R.; Harperink, S.; Rudolf, A.M.; Fleisch, E.; Haug, S.; Mair, J.L.; Salamanca-Sanabria, A.; Kowatsch, T. Factors Influencing Adherence to mHealth Apps for Prevention or Management of Noncommunicable Diseases: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e35371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prefeitura de São Paulo. Instrução de Alinhamento e Registros dos Dados do Farmacêutico no Sistemas de Informação em Centros de Atenção Psicossocial. Nota Técnica; Prefeitura de São Paulo: São Paulo, Brazil, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ministério da Saúde Brazil. Instrutivo Técnico da Rede de Atenção Psicossocial-Raps-no Sistema Único de Saúde-SUS [Internet]. Ministério da Saúde. 2022. Available online: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/instrutivo_tecnico_raps_sus.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Lopes Lima, O.J.; Lima, Â.R.A. Realização da evolução de enfermagem em âmbito hospitalar: Uma revisão sistemática. J. Nurs. Health 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.G.F.; Ramos, R.M.; Bitsch, J.Á.; Jonas, S.M.; Ix, T.; See, P.L.Q.; Wehrle, K. Psychologist in a Pocket: Lexicon Development and Content Validation of a Mobile-Based App for Depression Screening. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016, 4, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardisson Cirino Campos, F.A.; Arena Ventura, C.A.; Zanardo Mion, A.B.; Menéndez Rodríguez, T.D.; Biasotto Feitosa, F. Validação do protocolo de terapia familiar aplicado à saúde mental (PTF-SM1). J. Health NPEPS 2023, 8, e11095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minen, M.T.; Torous, J.; Raynowska, J.; Piazza, A.; Grudzen, C.; Powers, S.; Lipton, R.; Sevick, M.A. Electronic behavioral interventions for headache: A systematic review. J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| APA Guidelines | Psychosocial Rehab App | Recommendations from the Study by Martinez-Martin, Greely, and Cho (2021) [27] |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation of Evidence | Psychosocial rehabilitation project theory and principles of psychosocial rehabilitation theory [7,8,28]. | Evidence and Validity |

| Psychosocial Rehabilitation Theory [8] | A process that provides opportunities and/or facilitates (as well as supports and/or develops) psychiatric patients to achieve autonomy, independence, social functionality, a sense of purpose, social (re)insertion, and exercise of citizenship. This process utilizes individual and collective resources to benefit patients without violating their human rights. | |

| Assumptions of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Theory [8] |

| |

| Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project [8] | It is a systematized method of managing care and providing assistance for users of mental health services. Based on the psychosocial rehabilitation process, mental health professionals can diagnose problems, psychosocial needs, and demands of psychiatric patients. It enables professionals to plan and manage care, intervene, and mobilize resources within the psychosocial care network and/or community. Professionals can also make agreements and take responsibility for the care provided to the patients. They can monitor, (re)evaluate, and provide personalized, comprehensive, and humanistic assistance that focuses on full citizenship. | |

| Assumptions of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project [8] |

| |

| Risk Assessment, Privacy, and Security | Security and Privacy | |

| Transparency | ||

| Responsibility | ||

| Evaluation of ease of use | Validation of content, appearance, and usability with mental health professionals [31,32]. | |

| Interoperability/Interface | Usability inspection (validation) using Nielsen heuristics with technology and information professionals [33]. | |

| Clear, objective, and stigma-free language and functionalities adaptable to the user’s device [27,34,35,36,37]. | Social Justice | |

| Capacity to gather basic information/data | The Psychosocial Rehab App adapts the stages of the psychosocial rehabilitation project, allowing mental health professionals to collect information and data from psychiatric patients [7,28]. |

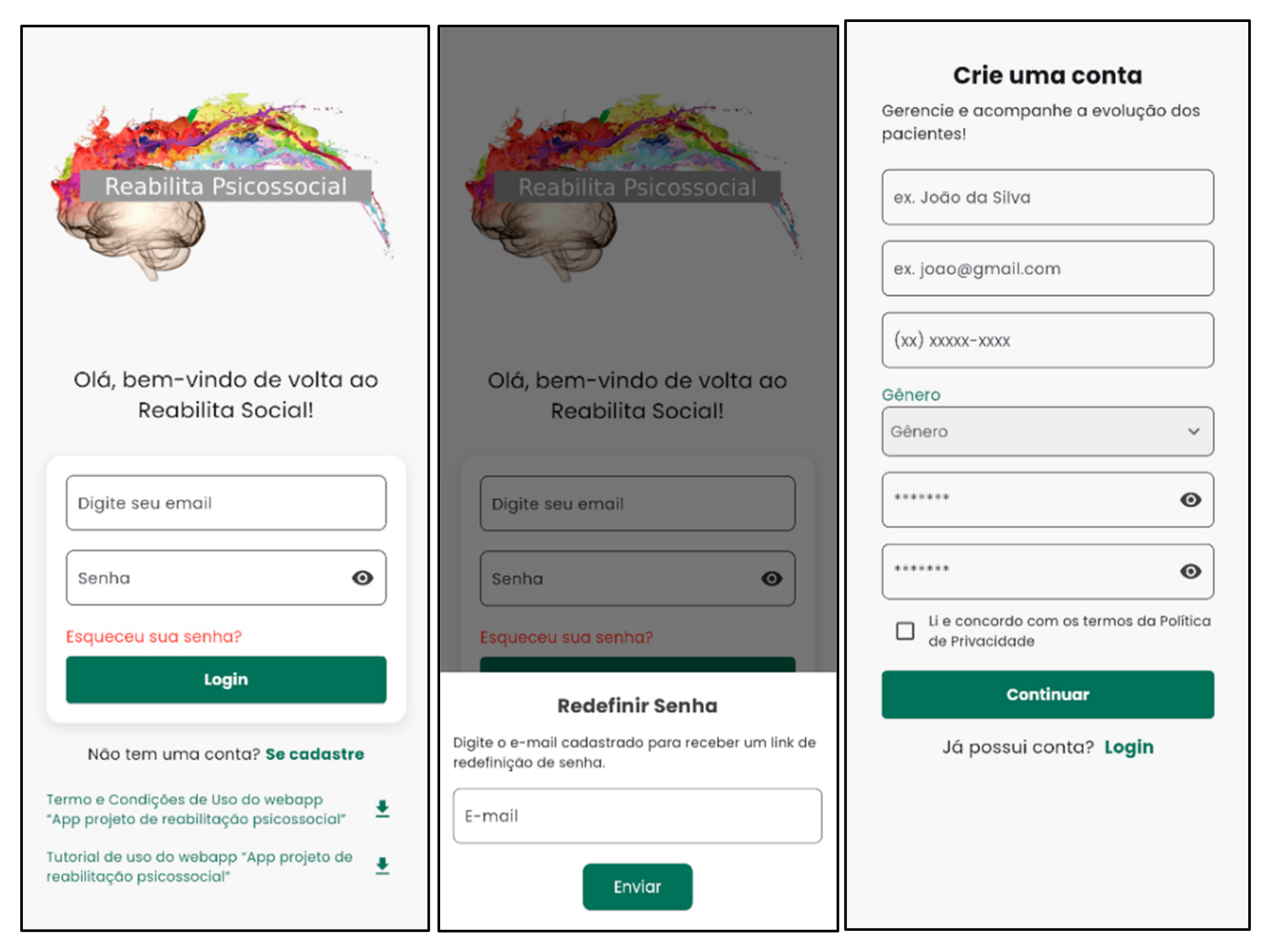

| Screens | Start with user registration by accepting the Terms and Conditions of Use of the Psychosocial Rehab App | Mental health professional | |||||

| Tutorial on how to use the Psychosocial Rehab App | |||||||

| Home | Short video about the psychosocial rehabilitation project (PRP) | ||||||

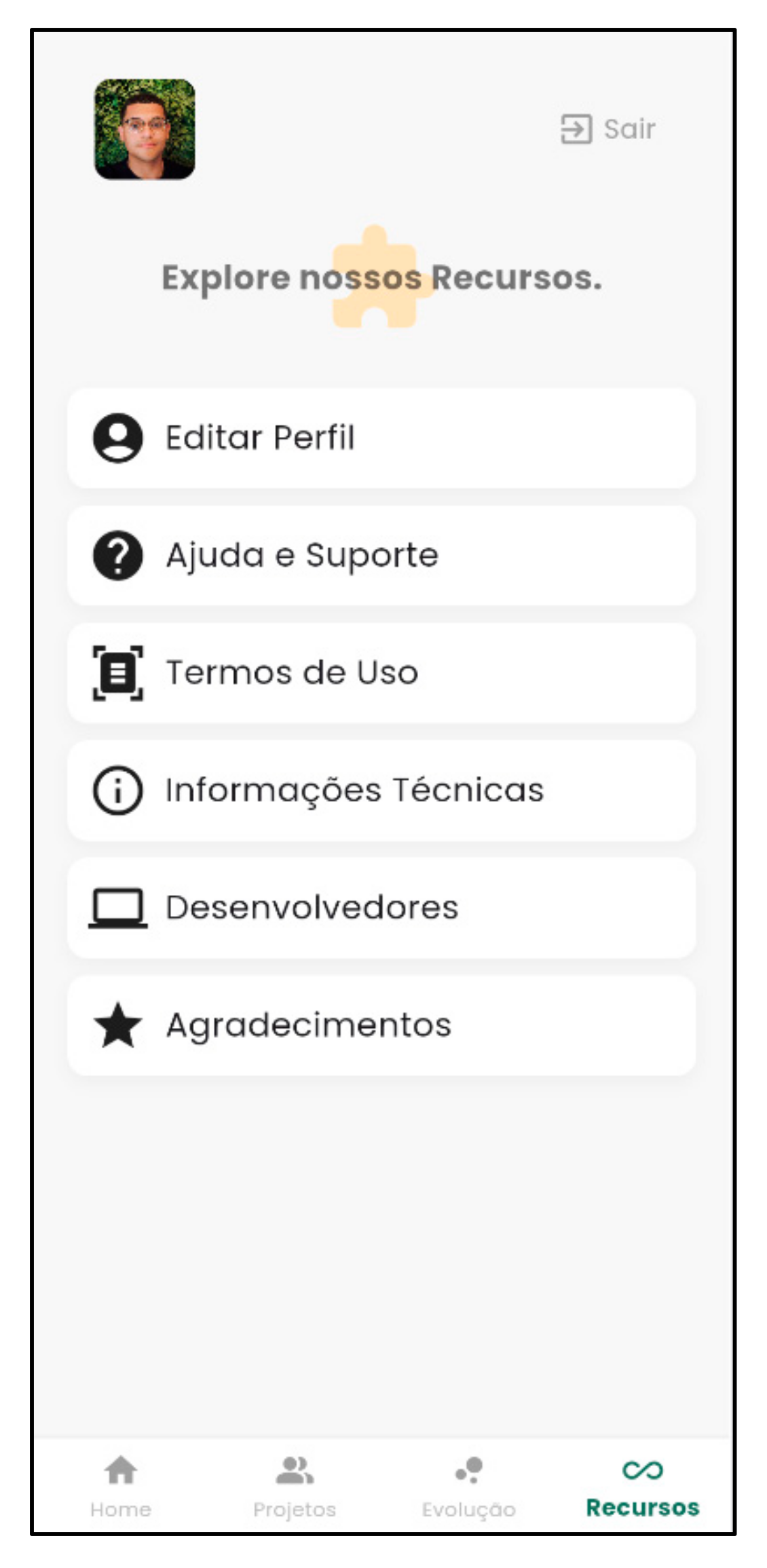

| Features | Edit Profile | Help and Support | Terms of Use | Technical Information | Developers | Acknowledgements | |

| Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project (See “add or search” function) | Patient Data (Registration) | Main Description | |||||

| Name, age, address, profession, income, support network, and reference technician. | |||||||

| Situational Diagnosis in Mental Health | Case history and multidisciplinary mental health diagnoses; individual resources and skills; potential, desires, and dreams; personal, collective, and structural difficulties; medications in use; clinical diseases; and other relevant information and identified problems. | ||||||

| Mental Health Care Goals | Short-term goals (less than 2 months), medium-term goals (6 to 12 months), and long-term goals (more than 12 months). | ||||||

| Mental Health Interventions | Problems, interventions, responsible parties, goals, and deadlines. | ||||||

| Agreements | Patient, family, reference technician, RAPS, others, interventions, and deadlines. | ||||||

| Case Study Agenda | Meeting date and time, agenda, and who is required to attend. | ||||||

| PRP Scheduled Assessment | Intervention/agreement, responsible party, compliance status, and observations. | ||||||

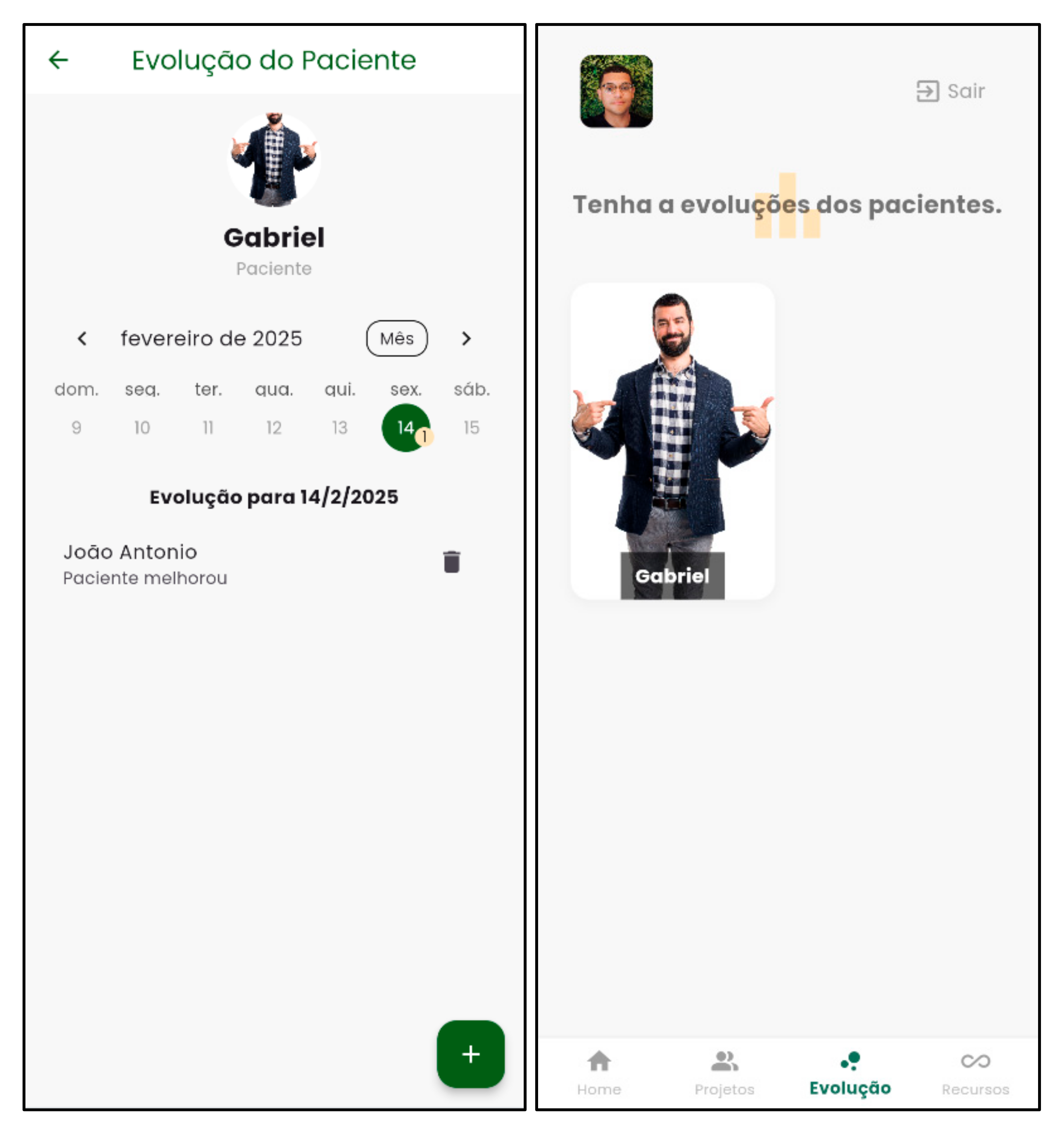

| Progression | Date and progression (spaces for inserting the progression text). | ||||||

| Functions | Share | Through the links, generate a PDF (print or save on hardware/cloud) or share via WhatsApp, email, etc. | |||||

| Mental Health Support Services | Search for RAPS services using the patient’s address. | ||||||

| Add New Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project | Add a “New Psychosocial Rehabilitation Project” using patient data. | ||||||

| Search Patient/Project | Search for a patient’s project by name to easily find it among several other projects. | ||||||

| Database | Firebase (offers a set of tools that simplify app development. These tools allow developers to focus on the logic and design of their apps, instead of worrying about their infrastructure). | ||||||

| Themes | Codes | Extracts |

|---|---|---|

| Constructing and improving the instructional design for the development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation App | Code:“Translation” and clarification of the prototypecarried out by the lead researcher to technology professionals | (…)-That’s my question. In “inserting the new psychosocial rehab project”, are the psychosocial rehabilitation projects patients? (ICT Professional 1).-Yes, they are patients. But in the sense (…) that for example, when a psychosocial rehab project is being created, when “inserting the new psychosocial rehab project” (…), the mental health professional inserts this project that is about the patient, and the idea is that the patient, their name and the project that is under construction or completed will appear (Lead Researcher).-Okay! Let’s examine if I understand this. So, the patient represents a psychosocial rehab project? (ICT Professional 1). (…)-This is a psychosocial rehab project for each patient, (…), so each patient will have a psychosocial rehab project, (…), which (…) (has) this structure (…): patient data, situational diagnosis, goals, interventions, agreements, case study, and evaluation agenda (Lead Researcher). |

| Code:Improvements made by developers to the prototype in a collaborative context | (…)-If we change the design, but keep all the features, is that okay? (ICT Professional 1).(…)-No problem! (Lead Researcher).-Perfect, then. So, we can leave the home page as a presentation of the app (…). This Start button here; would it be a kind of Start for the videos?!-(ICT Professional 1).-This part; it was just to show that this part of starting the Start… Now I realize that it doesn’t make sense… (…). Go back to the home page. (which) (…) was really cool. Let’s just keep it short. Let’s leave just one video. That way we won’t leave much information… (Lead Researcher). | |

| Code:Instructional Design for the Development of the Psychosocial Rehab App | (…)-We create the screen; we create its function. And then, for example, this one here, which is a screen that is under construction, we now start by taking so many details of it, we will first make it work, (…) then, you can use it as if it were really the app. What you can’t do, for example, is a field; you can’t write in it, precisely because it is a prototype, you know, it doesn’t have that type of function. For example, profile, exit, you can see the flow, what it is like, (…) here we already have a shadow of things; we have the cards (ICT Professional 1). | |

| Exchange of experience and collaborative work in the construction of the instructional design and development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation App | Code:Exchange of knowledge about mental health and technology | - (…) That’s why we’re talking about it, you know?! Because we’re really going to, we know that it’s not your responsibility, but the technology part, and that you’re more in that area. We’re going to take your idea and we’re going to bring it to technology. (…) (For example) This little screen here (calls the name of the lead researcher), it’s called Drawer. What’s Drawer? Drawer is when the person or the health professional clicks on their photo. And then this screen appears, it scrolls vertically, and the user’s profile information appears (…). (ICT Professional 1). (…) (Then the psychosocial rehab project is explained) it’s not limited to just what’s happening; it also considers the macro level, in establishing goals and interventions for the psychosocial rehab and quality of life of the patient (Lead Researcher). |

| Code:Collaborative work | (…)-This is also something about the image (design) that we didn’t think about at the beginning. We think about it as we go along. For example, you didn’t see a need for this at first. I saw a different need, so now we’re combining the two into something that makes sense. This will also happen during development (…) (ICT Professional 1).-And that will make things easier, right?! (Lead Researcher). (…)-Going back to the other screens, I think we’ve finished addressing the design issue, right?!… (…). (ICT Professional 1).-Yes! (Lead Researcher). (…) --It’s a part of the patient’s progression, which I think is a more differentiated part. Here it will be like a timeline showing the days of the publications… (…) (ICT Professional 1).-Great, and that was the real meaning of the progression. But remember that here it can’t be a mix of progression from all patients, just from this specific patient (…) (Lead Researcher). | |

| Development of the Psychosocial Rehab App with testing and feedback from the lead researcher | Code:Development, testing, and feedback from the lead researcher | (…)-That’s it, that’s good, that’s cool, okay? That’s what waiting means. Do you have any questions? (Lead Researcher).-Not yet, but in a little while. It’s coming up, it’s coming up (ICT Professional 1). (…) (It’s necessary to) Test it too, I’ve already uploaded it (the Psychosocial Rehab App) to the cloud. So, you can come in here and test it. It’ll be better for us (ICT Professional 2). (…)-Cool, cool. I’ll go in, but there’s not much. We just need to align what’s (here)… (Lead Researcher). (…)-(You) can look around (ICT Professional 2).-I’ll look around… just send me the link and my login information on WhatsApp… (…) We’re fixing it. It looks okay… The idea was cool, it is perfect (Lead Researcher). |

| Code:Operational difficulty of making the Psychosocial Rehab App usable | (…)-I might not link the project because there might not be any registrations yet. However, I would link the patients (…) together with the healthcare professional (ICT Professional 1).-Okay, but here, for example, if no one has the patient’s initial contact information, who will enter the CPF first? (…), And then we might have a problem with not being able to register…. (LeadResearcher).-You can leave that there. To (…) do it later, right, maybe… (ICT Professional 2). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cirino Campos, F.A.A.; Sánches García, J.C.; Galdino da Silva, G.L.; Araújo, J.A.L.; Farfán Ulloa, I.; Caritá, E.C.; Feitosa, F.B.; Moll, M.F.; Rodriguez, T.D.M.; Ventura, C.A.A. Development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Web Application (Psychosocial Rehab App). Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070228

Cirino Campos FAA, Sánches García JC, Galdino da Silva GL, Araújo JAL, Farfán Ulloa I, Caritá EC, Feitosa FB, Moll MF, Rodriguez TDM, Ventura CAA. Development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Web Application (Psychosocial Rehab App). Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(7):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070228

Chicago/Turabian StyleCirino Campos, Fagner Alfredo Ardisson, José Carlos Sánches García, Gabriel Lamarca Galdino da Silva, João Antônio Lemos Araújo, Ines Farfán Ulloa, Edilson Carlos Caritá, Fabio Biasotto Feitosa, Marciana Fernandes Moll, Tomás Daniel Menendez Rodriguez, and Carla Aparecida Arena Ventura. 2025. "Development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Web Application (Psychosocial Rehab App)" Nursing Reports 15, no. 7: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070228

APA StyleCirino Campos, F. A. A., Sánches García, J. C., Galdino da Silva, G. L., Araújo, J. A. L., Farfán Ulloa, I., Caritá, E. C., Feitosa, F. B., Moll, M. F., Rodriguez, T. D. M., & Ventura, C. A. A. (2025). Development of the Psychosocial Rehabilitation Web Application (Psychosocial Rehab App). Nursing Reports, 15(7), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15070228