Abstract

Background: The ageing of the population and the progressive increase in chronic diseases represent a major challenge for healthcare systems. The community nurse case manager (CNCM) is emerging as a key figure to provide comprehensive and continued care for complex and pluripathological chronic patients (CPCPs), especially after hospital discharge. Objective: The aim of this study is to pilot CNCMs in assisting CPCPs and assess their effects on functional capacity, cognitive performance, quality of life, readmissions, clinical parameters, satisfaction with home care, and caregiver overload. Methods: A comparative study will be carried out at two health centres in Salamanca (Spain). In both centres, CPCPs will continue to receive the interventions included in the Castilla y León Health System Portfolio from their primary care (PC) nurses. In the intervention centre, case management provided by a CNCM will be added. We will recruit 212 CPCPs with cardiac or respiratory disease and/or diabetes mellitus who are dependent for basic activities of daily living and have a programmed hospital discharge. An initial assessment will be performed at home after discharge, followed by assessments at 3, 6, and 12 months. Expected results: The intervention is anticipated to improve all study outcomes. Discussion: CNCMs may contribute to more proactive and individualised follow-up care for CPCPs and their caregivers, improving care coordination. Conclusions: This study will help to evaluate the feasibility and clinical relevance of incorporating the CNCM’s role into PC. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT06155591. The date of trial registration was 24 November 2023.

1. Introduction

Population ageing is a growing challenge [1,2]. Spain is the fourth European country with the highest proportion of people aged 65 and over, currently accounting for 17% of the total population, with projections reaching 37% in 2049 [3,4]. This trend will lead to an increased prevalence of chronic diseases and, consequently, a higher healthcare demand and resource consumption [5].

Chronic diseases, characterised by their prolonged course (lasting more than six months), slow progression, and multifactorial origin, significantly affect patients’ quality of life [6,7]. Among the most prevalent conditions are cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as diabetes mellitus (DM), which account for 80% of healthcare demand and 90% of mortality in Europe [8]. Furthermore, they represent the leading cause of disability and healthcare expenditure, posing a challenge for both individuals and healthcare systems [9,10].

Complex and pluripathological chronic patients (CPCPs) often present with multiple comorbidities, frailty, and clinical vulnerability, alongside a progressive decline in functional capacity [11,12,13]. This has a significant impact on healthcare demand, with considerable social and economic repercussions [9,14]. The CRONICOM project [15] revealed that 61% of patients hospitalised in internal medicine units were classified as complex chronic patients, and 40% were pluripathological, showing a deterioration in quality of life and an increased dependency following each hospital admission [16,17]. In this regard, various studies highlight the importance of collaboration and coordination between healthcare levels, as well as of the continuity of care, to prevent prolonged hospital stays, early readmissions, and delays in identifying decompensations [18,19,20].

Managing CPCPs requires a comprehensive, personalised, and holistic approach, with continuous monitoring to mitigate the impact of coexisting diseases. The key lies in a multidisciplinary approach that integrates medical treatment, patient education, and social and psychological support [21]. Internationally, several models have been developed for chronic disease care [22], prioritising the effective management of complex chronic cases [23,24,25]. In Spain, regional health services have implemented various strategies and plans for chronic disease care, following the guidelines of the Ministry of Health and scientific societies [26]. Many of these models have incorporated the figure of the nurse case manager (NCM), although its impact has not yet been systematically evaluated [27,28].

Within this role, two areas of practice can be distinguished: the community NCM (CNCM), responsible for managing highly complex patients, with planning and coordination functions mainly within the primary care (PC) setting [29,30], and the hospital NCM (HNCM), who ensures the continuity of care and oversees resource management across different healthcare levels [31].

Although studies on case management in this patient population remain limited, their findings are consistent with improved health-related quality of life, therapeutic adherence, functional capacity, and a more efficient use of healthcare resources, including fewer avoidable hospitalisations and urgency visits [32,33,34,35,36]. Several studies conducted in Spain have also obtained favourable results with this model [37,38]. Moreover, a positive impact on caregiver overload has been reported in some studies through health education, emotional support, and better coordination of care [39,40]. All these effects appear to be greater when implemented in PC [41].

Based on the above, population ageing and the increasing burden of chronic diseases represent a significant challenge that requires solutions in the coming years. The NCM role could play a crucial part in addressing this issue. However, the available studies are limited by short follow-up periods and methodological heterogeneity due to variability in the indicators used and the patient profiles included. Therefore, further research with greater methodological rigour and longer follow-up periods is required.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective

The aim of the present study is to pilot CNCMs in assisting CPCPs dependent for activities of daily living (ADLs) with cardiac and/or respiratory pathologies and/or diabetes mellitus from PC and assess their effect on functional capacity, cognitive performance, quality of life, readmissions, clinical parameters, satisfaction with home care, and the overload of the main caregiver.

2.2. Design and Setting

A comparative trial will be carried out in the health area of Salamanca (Spain), particularly in the Garrido Sur and Miguel Armijo health centres. Both are urban and have a population with similar characteristics, so they will serve as the intervention and control centre, respectively. The PC nurses at both centres will continue to perform the usual interventions for CPCPs included in the Portfolio of Services of the Castilla y León Health System (SACYL), and case management will be added through a CNCM at the intervention centre.

2.3. Participants

This study will include CPCPs who, after being hospitalised due to decompensation of their underlying pathologies, present home care needs at discharge. To be identified as CPCPs, they must meet the criteria established by the Spanish National Health System, which include the presence of two or more clinical categories of pluripathology and at least one complexity criterion. The detailed list of criteria is provided in Table S1.

2.3.1. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria are CPCPs with associated cardiac and/or respiratory pathologies and/or diabetes mellitus who present frailty criteria (Frail ≥ 1 point), require a main caregiver to perform ADLs (Barthel ≤ 60 points and/or grade II or III dependency recognised by Social Services), require home care and/or social resource management, and agree to sign (themselves or their legal guardians) informed consent to participate in this study.

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

The exclusion criteria are patients with other pathologies associated with complex pluripathology, those with non-habitual caregivers, and those who reside outside the area corresponding to the Garrido Sur and Miguel Armijo health centres, despite being assigned to them.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size was calculated taking into account the main study variables. Specifically, it was estimated to detect a difference equal to or greater than 15 points in the Barthel Index, accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in a bilateral contrast. Furthermore, the common standard deviation was assumed to be 34.8, as shown in the study by García-Fernández et al. [40], and a loss to follow-up rate of 20% was assumed due to the characteristics of the study subjects and the duration of follow-up. Therefore, it will be necessary to include 212 CPCPs (106 in each group) to detect statistically significant differences.

2.5. Variables and Measurement Instruments

Most of the variables will be collected by means of hetero-administered questionnaires, except for those on caregiver overload and user satisfaction, which will be self-administered.

2.5.1. Sociodemographic Variables

Data on age, sex, marital status, type of main caregiver (spouse, children, unpaid caregiver, or paid caregiver), and degree of dependency (II or III) will be collected at the initial assessment.

2.5.2. Primary Outcome Measures

Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)

These will be assessed using the Barthel Index, validated in the Spanish population and showing good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86–0.92), which evaluates a person’s ability to perform ten activities of daily living (eating, dressing and undressing, grooming, using the bathroom, sphincter control, bathing, moving around, and going up and down stairs), assigning up to 15 points to each according to the degree of autonomy. The minimum score is 0 and the maximum is 100. A person is considered totally dependent if their score is ˂20 points; severely dependent if it is between 25 and 60 points; moderately dependent if it is between 65 and 90 points; and mildly dependent if it is equal to 95 points [42].

Quality of Life

This will be assessed using the Spanish version of the COOP-WONCA test, which shows acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.73). This instrument relates the patient’s quality of life to their health during the last four weeks by asking about their physical fitness, feelings, daily activities, social activities, state of health, changes in their state of health, and pain by means of a drawing representing a degree of functioning with a 5-level Likert scale. Higher scores express worse levels of functioning/well-being [43].

Cognitive Performance

This will be explored through the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which consists of 30 items and lasts approximately 10–12 min. It helps to identify mild impairments in cognitive skills (orientation, short-term memory/delayed recall, executive function/visuospatial ability, language, abstraction, identification, and attention). The total score is 30 points; a score of 26 or higher is considered normal. Cronbach’s alpha for the Spanish version was 0.77 [44].

2.5.3. Secondary Outcome Measures

Clinical Variables

To assess some of the clinical variables, the devices listed below will be used and calibrated regularly according to the manufacturer’s recommendations:

- Blood pressure: the measurement will be taken using an OMRON M6 Comfort HEM-7321-E digital blood pressure monitor, taking three readings on the dominant arm with an interval of 1 min between them and using the average of the last two values according to the protocol of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) [45].

- Heart rate and oxygen saturation: it will be determined using an approved Beurer PO 45 portable pulse oximeter.

- Capillary glycosylated haemoglobin: the test will be performed with a validated Abbott Afinion analyser after obtaining a capillary blood sample by finger prick, using a sampling device that is inserted into the test cartridge [46].

- Capillary blood glucose: a capillary fingerstick blood sample will be taken at least 2 h after the last meal. The test will be performed with an approved Freestyle Glucometer.

- Degree of dyspnoea: this will be examined using the modified Medical Research Council Scale (mMRC), which consists of 5 levels. The higher the level, the lower the tolerance to activity due to dyspnoea [47].

- Symptoms attributable to heart disease: these will be assessed using the New York Heart Association (NYHA) Functional Classification. Class I patients have no symptoms, while those in classes II, III and IV have mild, moderate, and severe symptoms, respectively [48].

Number of Hospital Admissions

This will be quantified at all follow-up time points.

Number of Drugs Chronically Prescribed

This will be recorded from the electronic prescription of the CPCPs at discharge and at the end of follow-up.

Therapeutic Adherence

This will be calculated using a scale designed to assess the patient’s skills and knowledge of the prescribed treatment, with items adapted from the DRUGS and Med-Take scales. For each drug, the following criteria are scored with 1 or 0 points: whether the patient correctly identifies it and knows its indication, dosage, and method of administration. The maximum score is 4, multiplied by the total number of medicines. The assessment of overall adherence is made with the sum of the score obtained for each medication divided by the maximum score [49,50,51]. The scale has not been psychometrically validated in the literature, but it was developed and standardised through expert consensus for institutional use within the regional care programme for polymedicated patients.

Primary Caregiver Overload

This will be assessed with the Zarit scale, which consists of 22 questions with answers from 1 to 5 points, with a score ≥ 47 points being considered overburden. High internal consistency was obtained for this questionnaire (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.92) [52].

Frailty

The Frail questionnaire, consisting of 5 simple questions on fatigue, endurance, ambulation, comorbidity, and weight loss, will be used. Patients scoring 1 point or more are considered frail. The inter-rater correlation for this instrument was 0.82, indicating good external consistency [53].

User Satisfaction

This will be measured through the Satisfad Questionnaire 14, an instrument for evaluation by the patient or main caregiver of the home care services provided, which demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85). Each item is scored on a Likert scale, comprising 4 levels ordered categorically from 0 to 3 (where 0 corresponds to the minimum and 3 to the maximum). The resulting range of possible scores is from 0 to 42 points [54].

2.6. Data Collection

Data collection will be carried out by independent evaluators, who will be health professionals from the Salamanca Primary Care Management, with training in the use of the data collection form and the administration of the different tests, which will be paper-based.

The baseline assessment will take place at the patient’s home, and subsequent follow-up assessments will be arranged there or at the health centre depending on their progress:

- Initial assessment: the variables shown in Table 1 will be collected.

Table 1. Diagram of the study schedule. √ denotes the time points at which each procedure will be carried out. SACYL: Castilla y León Health System.

Table 1. Diagram of the study schedule. √ denotes the time points at which each procedure will be carried out. SACYL: Castilla y León Health System. - Three-, six-, and twelve-month assessment: the same variables as in the initial assessment will be collected, adding the number of readmissions and medicines prescribed, as well as the evaluation of the satisfaction of the user and/or main caregiver.

2.7. Intervention

2.7.1. Common to Both Centres

After planning a hospital discharge, the hospital liaison nurse (HLN) will schedule the CPCP in the agenda of the PC nurse corresponding to the patient in both centres, as usual. All of them will have access to the hospital discharge report via the unified hospital and primary care digital medical record and will contact the patient’s main caregiver to assess their existing needs at home. Moreover, they will continue to perform the usual interventions included in the SACYL Portfolio of Services for CPCP (Figure S1).

Likewise, the evaluators will call the family unit upon discharge from hospital, check the inclusion criteria for this study, explain the research project, and request the signature of the informed consent form if they wish to participate. Subsequently, the initial home assessment will be planned by collecting the data described in Table 1 and the next follow-up assessments at 3, 6, and 12 months will be reported.

2.7.2. Specific to the Intervention Centre

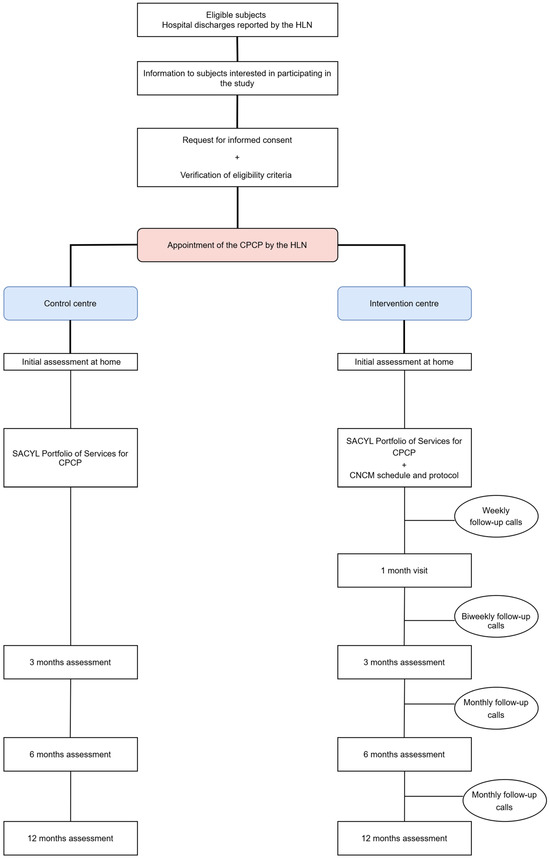

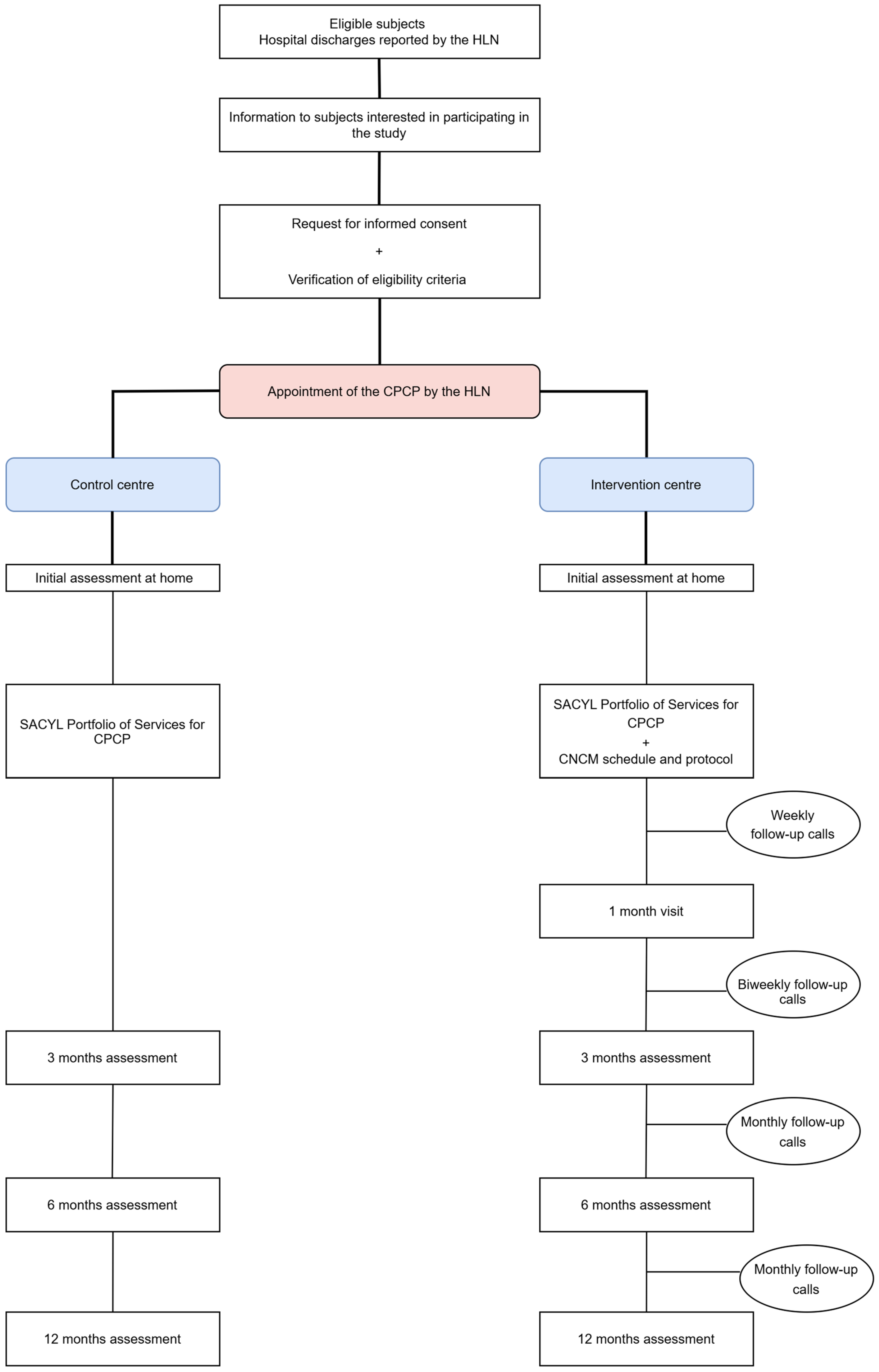

A CNCM action protocol (Figure 1) has been designed to be sequenced according to the circumstances in which the CPCPs find themselves:

- Pre-hospital discharge: The HLN will contact the CNCM to inform them of the imminent hospital discharge.

- Hospital discharge: The HLN will schedule the CPCP on the CNCM’s agenda, and the CNCM will arrange a home visit and carry out a comprehensive nursing assessment based on Marjory Gordon’s functional patterns. The main caregiver will be identified, and health education will be provided to improve home care. An infographic to identify the signs and symptoms of decompensation or exacerbation, as well as a direct-dial phone number, will also be given. The CNCM will then inform the PC team (physician, nurse, and social worker) about the patient’s situation and needs, managing necessary appointments or resources and coordinating care among professionals and levels.

- Post-hospital discharge proactive telephone monitoring: The CNCM will make comfort calls every week during the 1st month, every 15 days until 3 months from recruitment, and every month until 6 and 12 months (Table S2).

- One-month visit: The CNCM will perform a physical examination and assess adherence to treatment, the presence of decompensation/exacerbation of the process, the Barthel Index, and the satisfaction of the user or main caregiver.

- Occurrence of decompensation/exacerbation: If the patients and/or main caregivers report suspicious signs and/or symptoms through the direct dial telephone number, an appointment will be made with their PC physician that same day or, in the event of seriousness, urgency and/or emergency resources will be activated.

- Hospital readmission: The CNCM will be kept informed through the HLN and CPCP’s digital medical record. Once discharged, the process will return to the “hospital discharge” phase, and a new home visit will be scheduled to reassess the current situation.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants’ progress. CPCP: complex and pluripathological chronic patient. CNCM: community nurse case manager. HLN: hospital liaison nurse. SACYL: Castilla y León Health System.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participants’ progress. CPCP: complex and pluripathological chronic patient. CNCM: community nurse case manager. HLN: hospital liaison nurse. SACYL: Castilla y León Health System.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

The normality of the variables will be analysed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous variables will be presented as mean ± standard deviation, or as median and interquartile range in the case of a non-normal distribution. Qualitative variables will be expressed as number and percentage. The association between qualitative variables will be analysed with the chi-square test or Fisher’s test, as appropriate. Comparisons between quantitative variables will be carried out using Student’s t-test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test for independent measurements and paired Student’s t-test for related measurements. A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be performed to assess the effect of the intervention between study centres. Covariates will be included in the model to control for potential confounders such as baseline functional status, comorbidities, or characteristics of the main caregiver. An alpha risk of 0.05 will be set as the limit of statistical significance for bilateral hypothesis testing. Data will be analysed with SPSS statistical software version 28.0.

2.9. Strengths and Methodological Limitations of This Study

Although this study follows all the recommendations for non-randomised interventional studies included in the TREND statement, there is a possibility of confounding factors not considered. As this study will be conducted in CPCPs, the loss rate is expected to be high, because their characteristics may prevent them from completing the follow-up due to institutionalisation or death. Given the nature of this study, subjects will not be blinded to the intervention, but the investigator in charge of analysing the data will not be aware of the centre allocation.

3. Expected Results

Based on the study objectives and the existing literature, we anticipate that patients in the intervention group will show improvements in functional capacity, health-related quality of life, cognitive performance, clinical parameters, and satisfaction with the care received. In addition, a reduction in hospital readmissions and caregiver burden is hypothesised.

The findings will also provide insight into the feasibility and potential impact of this professional profile in PC, with results interpreted in light of the clinical and social complexity of the target population.

4. Discussion

Despite the implementation of different management models and care strategies for patients with multiple chronic conditions, they continue to experience a significant decline in functional capacity, a deterioration in quality of life, delayed detection of signs or symptoms of decompensation, and worsening therapeutic adherence, leading to an increase in hospital readmissions.

Therefore, it is essential to establish health policies that promote comprehensive care based on a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach. These strategies should ensure patient- and family-centred care, fostering shared decision-making. Likewise, it is crucial to actively involve patients in the various processes related to their chronic pathologies, with a particular emphasis on self-care and empowerment. In this context, the NCM emerges as a key figure to lead this model, while PC represents the optimal setting for its implementation, as it is the level of care closest to the community and best positioned to respond to patients’ needs.

In this regard, the incorporation of CNCMs in PC could enhance comprehensive patient and family care. Through home-based monitoring, these professionals would facilitate the early detection of changing needs, favour a prompt response to emerging health issues, and optimise the use of available resources, guaranteeing more coordinated and efficient care. However, despite its potential, experience with this professional role in PC remains limited in Spain. This study aims to generate comparative data that may help assess its applicability in the community context and support decision-making in chronic care planning.

Thus, the recognition of the CNCM as a professional category within the Castilla y León health system, following the results of this project, could contribute to cost reduction and improved quality of care by reducing care fragmentation and ensuring integrated, patient- and environment-centred care. Even so, this study has some limitations, including the non-randomised design and the reduced sample size. Nevertheless, conducting it under real-world conditions will allow for the generation of contextualised evidence.

5. Conclusions

This study might help to determine whether interventions led by CNCMs in PC offer benefits compared to usual follow-up for patients with complex chronic conditions and functional dependence. The resulting evidence may support decisions on the organisation of community-based care, promoting models that enhance care continuity, self-care, and health system efficiency.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep15060191/s1, Figure S1: Interventions for complex pluripathological chronic patients (CPCPs) in the Portfolio of Services of the Castilla y León Health System (SACYL); Table S1: Spanish National Health System criteria to identify complex and pluripathological chronic patients (CPCPs); Table S2: Guidance for proactive telephone follow-up by the community nurse case manager (CNCM).

Author Contributions

V.I.-S., N.S.-A. and R.A.-D. conceived and designed this study. V.I.-S., N.S.-A. and R.A.-D. drafted the study protocol. N.S.-A., R.A.-D., J.I.R.-R. and L.G.-O. provided methodological and statistical expertise. V.I.-S. is responsible for study management, staff training, and supervision. V.I.-S. manages day-to-day study responsibilities, including recruitment monitoring and liaison with recruitment sites. V.I.-S., N.S.-A., R.A.-D., J.I.R.-R., B.S.-S. and L.G.-O. are involved in data collection. V.I.-S., N.S.-A. and R.A.-D. wrote the manuscript. N.S.-A. and R.A.-D. conducted the final revision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by research grants from the Dirección General de Calidad e Infraestructuras Sanitarias de Castilla y León for research projects in biomedicine, health management, and socio-health care (GRS 2490/B/22) within the framework of the 2022 programme for the promotion of research activity in nurses (BOCYL-D-15062022-40). Additional funding was provided by the Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Enfermería de España and the Instituto Español de Investigación Enfermera through the 2022 award for the best research project in the family and community field (PNI22_CGE14), as well as by the Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Salamanca under its intensification programme (INT/ext23/005). Furthermore, it has also been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through RD21/0016/0010 (Network for Research on Chronicity, Primary Care, and Health Promotion—RICAPPS), financed by the European Union—Next Generation EU, Recovery and Resilience Facility (MRR). None of these funders played a role in the study design, data analysis, result reporting, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research with Medicines of the Salamanca Health Area (protocol code, PI 2022 07 1123; date of approval, 11 July 2022). Confidentiality will be guaranteed in accordance with the provisions of Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights, as well as Law 14/2007 on biomedical research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent will be obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets that will be used and/or analysed during the present study will be available upon request from the corresponding author.

Public Involvement Statement

There is no public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the TREND statement for non-randomised interventional studies.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the professionals participating in this study and the members of the research team: V Iglesias-Sierra, N Sánchez-Aguadero, R Alonso-Domínguez, JI Recio-Rodríguez, B Sánchez-Salgado, EM Luengo-Celador, MC García-Rodríguez, B Rodriguez-Martín, T Redondo-Soria, MJ Prieto-Santos, and R Polo Hernández.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADLs | Activities of Daily Living |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| CNCM | Community Nurse Case Manager |

| CPCP | Complex and Pluripathological Chronic Patients |

| DM | Diabetes Mellitus |

| ESH | European Society of Hypertension |

| HLN | Hospital Liaison Nurse |

| HNCM | Hospital Nurse Case Manager |

| mMRC | Medical Research Council Scale |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| NYHA | New York Heart Association |

| NCM | Nurse Case Manager |

| PC | Primary Care |

| SACYL | Castilla y León Health System |

References

- Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/envejecimiento-y-salud (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- United Nations. World Social Report 2023: Leaving No One Behind in An Ageing World; United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2023; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Díaz, J.; Ramiro Fariñas, D.; Aceituno Nieto, P.; Escudero Martínez, J.; Bueno López, C.; Castillo Belmonte, A.B.; De Las Obras-Loscertales Sampériz, J.; Fernández Morales, I.; Villuendas Hijosa, B. Un Perfil de las Personas Mayores en España, 2023. Indicadores Estadísticos Básicos; Informes Envejecimiento en red; Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC): Madrid, Spain, 2023; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Oficina de Ciencia y Tecnología del Congreso de los Diputados. Envejecimiento y Bienestar; Informes C; Oficina de Ciencia y Tecnología del Congreso de los Diputados (Oficina C): Madrid, Spain, 2023; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Nolte, E.; Knai, C.; Saltman, R.B. (Eds.) Assessing Chronic Disease Management in European Health Systems: Concepts and Approaches; European Observatory Health Policy Series; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014; ISBN 978-92-890-5030-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization. Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions: Organizing and Delivering High Quality Care for Chronic Noncommunicable Diseases in the Americas; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-92-75-11738-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (SEMI); Sociedad Española de Medicina de Familia y Comunitaria (semFYC); Federación de Asociaciones de Enfermería Comunitaria y Atención Primaria (FAECAP). Desarrollo de Guías de Práctica Clínica en Pacientes con Comorbilidad y Pluripatología; Sociedad Española de Medicina Interna (SEMI): Madrid, Spain, 2013; ISBN 978-84-695-7582-6. [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen, E. REPORT on Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs); European Parliament. Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Modelling and Prediction of Global Non-Communicable Diseases. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson-Stuttard, J.; Ezzati, M.; Gregg, E.W. Multimorbidity—A Defining Challenge for Health Systems. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4, e599–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Blázquez, M.; Sánchez Gómez, S.; Fuentelsaz Gallego, C. El Cuidado Como Elemento Transversal En La Atención a Pacientes Crónicos Complejos. Enfermería Clínica 2014, 24, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohórquez Colombo, P.; Nieto Martín, M.D.; Pascual de la Pisa, B.; García Lozano, M.J.; Ortiz Camúñez, M.Á.; Bernabéu Wittel, M. Validación de Un Modelo Pronóstico Para Pacientes Pluripatológicos En Atención Primaria: Estudio PROFUND En Atención Primaria. Atención Primaria 2014, 46, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollero Baturone, M.; Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Espinosa Almendro, J.M.; García Estepa, R.; Morilla Herrera, J.C.; Pascual de la Pisa, B.; Rodríguez Fernández, M.D.; Santos Ramos, B.; Sanz Amores, R. Atención a Pacientes Pluripatológicos: Proceso Asistencial Integrado, 3rd ed.; Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Salud: Sevilla, Spain, 2018; ISBN 978-84-947313-4-1. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M.; Lapointe, L.; Hudon, C.; Vanasse, A.; Ntetu, A.L.; Maltais, D. Multimorbidity and Quality of Life in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 2, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez Mancera, R. Impacto de los Pacientes con Enfermedades Crónicas y Necesidades Complejas de Salud en Medicina Interna: Proyecto CRONICOM; Universidad de Sevilla: Sevilla, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Coronado-Vázquez, V.; Casto, M.M.; Martínez, T.; Cortés, I.D.; Galbarro, J.; Ibáñez, C. Evaluation of the Impact of Clinical, Functional and Social Factors on the Readmission of Patients with Pluripathologies. J. Aging Res. Healthc. 2016, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu-Wittel, M.; Ollero-Baturone, M.; Nieto-Martín, D.; García-Morillo, S.; Goicoechea-Salazar, J. Patient-Centered Care for Older Adults with Multiple Chronic Conditions: These Are the Polypathological Patients! J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2013, 61, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J.; Panagioti, M.; Alam, R.; Checkland, K.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S.; Bower, P. Effectiveness of Case Management for “At Risk” Patients in Primary Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo Maroto, I.; Fernández Moyano, A. Continuidad asistencial en el paciente pluripatológico. Med. Clin. 2012, 139, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguélez-Chamorro, A.; Casado-Mora, M.I.; Company-Sancho, M.C.; Balboa-Blanco, E.; Font-Oliver, M.A.; Román-Medina Isabel, I. Enfermería de Práctica Avanzada y gestión de casos: Elementos imprescindibles en el nuevo modelo de atención a la cronicidad compleja en España. Enfermería Clínica 2019, 29, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.; Mercer, S.W. Challenges of Managing People with Multimorbidity in Today’s Healthcare Systems. BMC Fam. Pract. 2015, 16, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodchis, W.P.; Dixon, A.; Anderson, G.M.; Goodwin, N. Integrating Care for Older People with Complex Needs: Key Insights and Lessons from a Seven-Country Cross-Case Analysis. Int. J. Integr. Care 2015, 15, e021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuño Solinís, R. Buenas Prácticas En Gestión Sanitaria: El Caso Kaiser Permanente. Rev. De Adm. Sanit. Siglo XXI 2007, 5, 283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Santaeugènia i Gonzàlez, S.J. Efectivitat d’un Nou Model d’atenció Integrada Geriàtrica En El Marc d’una Organització Sanitària Integral. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, E.H. Chronic Disease Management: What Will It Take to Improve Care for Chronic Illness? Eff. Clin. Pract. 1998, 1, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Minué-Lorenzo, S.; Fernández-Aguilar, C. Visión Crítica y Argumentación Sobre Los Programas de Atención de La Cronicidad En Atención Primaria y Comunitaria. Atención Primaria 2018, 50, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad. Servicios Sociales e Igualdad Estrategia para el Abordaje de la Cronicidad en el Sistema Nacional de Salud; Ministerio de Sanidad: Marid, Spain, 2012.

- Jadad, A.R.; Cabrera León, A.; Lyons, R.F.; Martos Pérez, F.; Smith, R. When People Live with Multiple Chronic Diseases: A Collaborative Approach to an Emerging Global Challenge; Andalusian School of Public Health: Granada, Spain, 2010; ISBN 978-84-693-2470-7. [Google Scholar]

- Carrier, J.; Newbury, G. Managing Long-Term Conditions in Primary and Community Care. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2016, 21, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, A.D.M.; Sandhi, A. Implementation of Nursing Case Management to Improve Community Access to Care: A Scoping Review. Belitung Nurs. J. 2021, 7, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D.D. Case Managers Optimize Patient Safety by Facilitating Effective Care Transitions. Prof. Case Manag. 2007, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatar, D.; Bondmass, M.; Ghitelman, J.; Avitall, B. Outcomes of Chronic Heart Failure. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askerud, A.; Conder, J. Patients’ Experiences of Nurse Case Management in Primary Care: A Meta-Synthesis. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2017, 23, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D.; Hayter, M. Structured Review: Evaluating the Effectiveness of Nurse Case Managers in Improving Health Outcomes in Three Major Chronic Diseases. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 2978–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, P. Telephone Follow-up for Patients Eligible for Cardiac Rehab: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Card. Nurs. 2014, 9, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carswell, P. Te Whiringa Ora: Person-Centred and Integrated Care in the Eastern Bay of Plenty, New Zealand. Int. J. Integr. Care 2015, 15, e014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, G.; Izquierdo, M.D.; Pérez, G.; Artiles, J.; Aguirre, A.; Cueto, M. La Enfermera Comunitaria de Enlace: Una Propuesta de Mejora En Atención Domiciliaria. Bol. Enferm. Comunit 2002, 8, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Asencio, J.; Gonzalo-Jiménez, E.; Martin-Santos, F.; Morilla-Herrera, J.; Celdráan-Mañas, M.; Carrasco, A.M.; García-Arrabal, J.; Toral-López, I. Effectiveness of a Nurse-Led Case Management Home Care Model in Primary Health Care. A Quasi-Experimental, Controlled, Multi-Centre Study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Melgarejo, L.; Carreño Moreno, S.; Chaparro-Diaz, L.; Quintero González, L.A.; Garcia-Quintero, D.; Carrillo-Algarra, A.J.; Castiblanco-Montañez, R.A.; Hernandez-Zambrano, S.M. Effectiveness of a Case Management Model for People with Multimorbidity: Mixed Methods Study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 3830–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, F.P.; Arrabal-Orpez, M.J.; Rodríguez-Torres, M.d.C.; Gila-Selas, C.; Carrascosa-García, I.; Laguna-Parras, J.M. Effect of Hospital Case-Manager Nurses on the Level of Dependence, Satisfaction and Caregiver Burden in Patients with Complex Chronic Disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 2814–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Briz, V.; Gómez Romero, R.; de Miguel-Montoya, I.; Juárez-Vela, R.; Martínez-Riera, J.R.; Mármol-López, M.I.; Verdeguer-Gómez, M.V.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, Á.; Gea-Caballero, V. Results of Nurse Case Management in Primary Heath Care: Bibliographic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 9541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaola-Sagardui, I. Validation of the Barthel Index in the Spanish population. Enferm. Clin. 2018, 28, 210–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizán Tudela, L.; Reig Ferrer, A. La Evaluación de La Calidad de Vida Relacionada Con La Salud En La Consulta: Las Viñetas COOP/WONCA. Atención Primaria 2002, 29, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, C.; Araneda, A.; Behrens, M.I. Validation of the Spanish-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test in adults older than 60 years. Neurologia 2019, 34, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuseppe, M.; Reinhold, K.; Mattias, B.; Michel, B.; Guido, G.; Andrzej, J.; Lorenza, M.M.; Konstantinos, T.; Enrico, A.-R.; Elhady, A.E.A.; et al. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension: Endorsed by the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) and the European Renal Association (ERA): Erratum. J. Hypertens. 2023, 41, 1874–2071. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, W.D.; Kupfer, K.; Little, R.R.; Amar, M.; Horowitz, B.; Godbole, N.; Hvidsten Swensen, M.; Li, Y.; San George, R.C. Accuracy and Precision of a Point-of-Care HbA1c Test. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2020, 14, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunjaya, A.; Poulos, L.; Reddel, H.; Jenkins, C. Qualitative Validation of the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnoea Scale as a Patient-Reported Measure of Breathlessness Severity. Respir. Med. 2022, 203, 106984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamp, K.D.; Prasun, M.A.; McCoy, T.P.; Rathman, L. Providers’ Accuracy in Decision-Making with Assessing NYHA Functional Class of Patients with Heart Failure after Use of a Classification Guide. Heart Lung 2022, 54, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelberg, H.K.; Shallenberger, E.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Wei, J.Y. One-Year Follow-up of Medication Management Capacity in Highly Functioning Older Adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2000, 55, M550–M553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raehl, C.L.; Bond, C.; Woods, T.J.; Patry, R.A.; Sleeper, R.B. Screening Tests for Intended Medication Adherence Among the Elderly. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 888–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio de Salud de Castilla y León Programa del Paciente Polimedicado. Available online: https://www.saludcastillayleon.es/portalmedicamento/es/estrategias-programas/programa-paciente-polimedicado (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Martin-Carrasco, M.; Otermin, P.; Pérez-Camo, V.; Pujol, J.; Agüera, L.; Martín, M.J.; Gobartt, A.L.; Pons, S.; Balañá, M. EDUCA Study: Psychometric Properties of the Spanish Version of the Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale. Aging Ment. Health 2010, 14, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Benito, M.Á.; Martín-Lesende, I. Frailty in primary care: Diagnosis and multidisciplinary management. Aten. Primaria 2022, 54, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales Asencio, J.M.; Bonill de Las Nieves, C.; Celdrán Mañas, M.; Morilla Herrera, J.C.; Martín Santos, F.J.; Contreras Fernández, E.; San Alberto Giraldos, M.; Castilla Soto, J. Design and validation of a home care satisfaction questionnaire: SATISFAD. Gac. Sanit. 2007, 21, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).