Lessons Learned from Governance and Management of Virtual Hospital Initiatives: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction and Qualitative Analysis

2.3. Quality Assessment

3. Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications for Healthcare Organizations

5.2. Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leff, B.; DeCherrie, L.V.; Montalto, M.; Levine, D.M. A research agenda for hospital at home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 1060–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.Y.; West, D.J., Jr. Hospital at home: An evolving model for comprehensive healthcare. Glob. J. Qual. Saf. Healthc. 2021, 4, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detollenaere, J.; Van Ingelghem, I.; Van den Heede, K.; Vlayen, J. Systematic literature review on the effectiveness and safety of paediatric hospital-at-home care as a substitute for hospital care. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2023, 182, 2735–2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentur, N. Hospital at home: What is its place in the health system? Health Policy 2001, 55, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagala, S.G.; Gupta, V.; Kumawat, S.; Anamika, F.; McGillen, B.; Jain, R. Hospital at home: Emergence of a high-value model of care delivery. Egypt. J. Intern. Med. 2023, 35, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, M.Q.; Lim, C.W.; Lai, Y.F. Comparison of Hospital-at-Home models: A systematic review of reviews. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e043285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaddoura, A.; Yazdan-Ashoori, P.; Kabali, C.; Thabane, L.; Haynes, R.B.; Connolly, S.J.; Van Spall, H.G.C. Efficacy of hospital at home in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, J.; Weiland, T.J.; Jelinek, G. Efficacy of hospital in the home services providing care for patients admitted from emergency departments: An integrative review. JBI Evid. Implement. 2014, 12, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichitvanichphong, S.; Kerr, D.; Talaei-Khoei, A.; Ghapanchi, A.H. Analysis of research in adoption of assistive technologies for aged care. In Proceedings of the 24th Australasian Conference on Information Systems, Melbourne, Australia, 4–6 December 2013; RMIT University: Melbourne, Australia, 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ghapanchi, A.H.; Aurum, A.; Daneshgar, F. The impact of process effectiveness on user interest in contributing to the open source software projects. J. Softw. 2012, 7, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purarjomandlangrudi, A.; Chen, D.; Nguyen, A. A systematic review approach to technologies used for learning and education. Int. J. Learn. Change 2015, 8, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghapanchi, A.H.; Jafarzadeh, M.H.; Khakbaz, M.H. An Application of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) for ERP system selection: Case of a petrochemical company. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems, Paris, France, 14–17 December 2008; Association for Information Systems: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ghapanchi, A.H.; Aurum, A. The impact of project licence and operating system on the effectiveness of the defect-fixing process in open source software projects. Int. J. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2011, 8, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.R.; Young, B.A.; Fox, S.J.; Cleland, C.J.; Walker, R.J.; Masakane, I.; Herold, A.M. The home hemodialysis hub: Physical infrastructure and integrated governance structure. Hemodial. Int. 2015, 19, S8–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, P. Hospital-at-Home: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Popul. Health Manag. 2023, 26, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson, M.R.; Shulman, E.P.; Dunn, A.N.; Fazio, J.R.; Habermann, E.B.; Matcha, G.V.; McCoy, R.G.; Pagan, R.J.; Maniaci, M.J. Implementation of a virtual and in-person hybrid hospital-at-home model in two geographically separate regions utilizing a single command center: A descriptive cohort study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2023, 23, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mader, S.L.; Medcraft, M.C.; Joseph, C.; Jenkins, K.L.; Benton, N.; Chapman, K.; Donius, M.A.; Baird, C.; Harper, R.; Ansari, Y. Program at home: A Veterans Affairs Healthcare Program to deliver hospital care in the home. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benz, C.; Middleton, A.; Elliott, A.; Harvey, A. Physiotherapy via telehealth for acute respiratory exacerbations in paediatric cystic fibrosis. J. Telemed. Telecare 2023, 29, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Barahimi, H.; Rosengaus, L.; Findikaki, H.; Williams, E.; Ribeira, R.; Matheson, L.; Westphal, C.; Qureshi, L.; Festus, N. Transforming the ED Fast Track to a Virtual Visit Track to Reduce Emergency Department Length of Stay Stanford Medicine. 2023. Available online: https://maryland.himss.org/sites/hde/files/media/file/2023/08/11/stanford-medicine-himss-davies-2023-telehealth-in-the-ed-final.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Lim, S.M.; Island, L.; Horsburgh, A.; Maier, A.B. Home first! identification of hospitalized patients for home-based models of care. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 413–417.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, D.; Conley, J. The next frontier of remote patient monitoring: Hospital at home. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e42335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.J.; Edwards, B.; Langelier, D.M.; Chang, E.K.; Chafranskaia, A.; Jones, J.M. Delivering virtual cancer rehabilitation programming during the first 90 days of the COVID-19 pandemic: A multimethod study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzitari, M.; Arnal, C.; Ribera, A.; Hendry, A.; Cesari, M.; Roca, S.; Pérez, L.M. Comprehensive Geriatric hospital at home: Adaptation to referral and case-mix changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2023, 24, 3–9.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toles, M.; Leeman, J.; McKay, M.H.; Covington, J.; Hanson, L.C. Adapting the Connect-Home transitional care intervention for the unique needs of people with dementia and their caregivers: A feasibility study. Geriatr. Nurs. 2022, 48, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, A.T.; Vognar, L.; Stuck, A.R.; McBride, C.; Scott, R.; Crowley, C. Integra at Home: A flexible continuum of in-home medical care for older adults with complex needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2024, 72, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Thoracic Society Guideline Development Group. Intermediate care—Hospital-at-Home in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: British Thoracic Society guideline. Thorax 2007, 62, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzosa, E.; Gorbenko, K.; Brody, A.A.; Leff, B.; Ritchie, C.S.; Kinosian, B.; Ornstein, K.A.; Federman, A.D. “At home, with care”: Lessons from New York City home-based primary care practices managing COVID-19. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2021, 69, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.M.; Rotteau, L.; Feldman, S.; Lamb, M.; Liang, K.; Moser, A.; Mukerji, G.; Pariser, P.; Pus, L.; Razak, F. A novel collaborative care program to augment nursing home care during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23, 304–307.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchener, K.; Coombs, L.A.; Dumas, K.; Beck, A.C.; Ward, J.H.; Mooney, K. Huntsman at Home, an oncology hospital at home program. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2021, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightwood, R.; Brimblecombe, F.; Reinhold, J.; Burnard, E.; Davis, J. A London trial of home care for sick children. Lancet 1957, 269, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Country | Study Design | HITH Program Type | Primary Focus Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paulson et al. (2023) [19] | USA | Descriptive cohort | Hybrid virtual/in-person acute care | Patient selection, governance structure |

| Mader et al. (2008) [20] | USA | Program evaluation | Hospital substitution (CAP, CHF, COPD, cellulitis) | Care delivery model, financial sustainability |

| Benz et al. (2023) [21] | Australia | Case study | Pediatric telehealth physiotherapy | Technology integration, hybrid care model |

| Nair et al. (2023) [22] | USA | Implementation study | Virtual visit track for ED patients | Technology integration, care coordination |

| Lim et al. (2024) [23] | Singapore | Implementation study | General acute HITH | Patient selection, remote monitoring |

| Whitehead & Conley (2023) [24] | USA | Review/commentary | Remote patient monitoring in HITH | Technology integration, patient outcomes |

| Lopez et al. (2021) [25] | Canada | Program evaluation | Virtual cancer rehabilitation | Technology adaptation, pandemic response |

| Inzitari et al. (2021) [26] | Spain | Observational study | Geriatric HITH during COVID-19 | Care model adaptation, patient outcomes |

| Toles et al. (2023) [27] | USA | Implementation study | Transitional care for dementia patients | Care coordination, patient-centered approaches |

| Fulton et al. (2022) [28] | USA | Program description | Comprehensive in-home care for complex needs | Governance, financial sustainability, partnerships |

| Marshall et al. (2015) [14] | New Zealand | Program evaluation | Home hemodialysis | Governance structure, training, infrastructure |

| BTS Guidelines (2007) [29] | UK | Clinical guideline | COPD hospital-at-home | Clinical responsibility, team leadership |

| Franzosa et al. (2021) [30] | USA | Qualitative study | Home-based primary care during COVID-19 | Pandemic adaptation, care delivery |

| Wong et al. (2022) [31] | Canada | Program description | Collaborative nursing home care | Cross-sector collaboration, pandemic response |

| Titchener et al. (2021) [32] | USA | Program description | Oncology hospital-at-home | Patient selection, external partnerships |

| Lightwood et al. (1957) [33] | UK | Historical trial | Pediatric home care | Early home care model, outcomes |

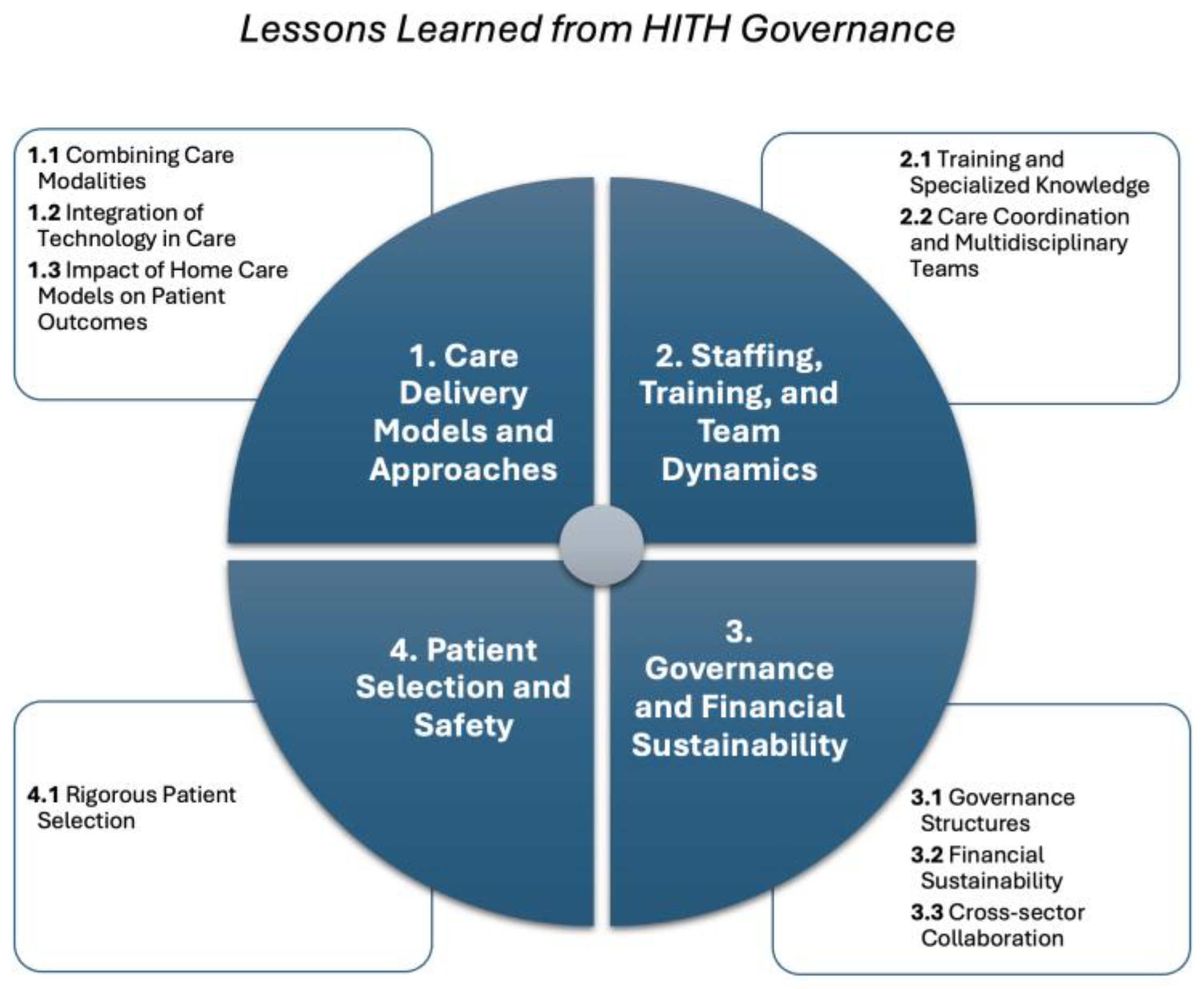

| Theme | Category | Lessons Learned * | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Care Delivery Models and Approaches | 1. Combining care modalities | 1.1.1. Combining virtual physicians with bedside nurses and vendor-managed supply chains can deliver acute care outside traditional hospital settings. | Paulson et al. [19] |

| 1.1.2. Combining virtual and in-person care increased patient volume, lowered costs, and enhanced scalability by using external vendors. | [19] | ||

| 1.1.3. The admission process is easier and less urgent for patients transitioning from an inpatient bed compared to those coming from the emergency department or clinic. Mader et al. [9] demonstrated this in their Veterans Affairs program treating community-acquired pneumonia, congestive heart failure, COPD, and cellulitis, where inpatient transfers showed smoother care transitions. | [20] | ||

| 1.1.4. Employing a hybrid telehealth physiotherapy model increased staff flexibility to accommodate physiotherapy sessions before and after school, as additional travel time during these peak traffic periods makes home visits inaccessible. | [21] | ||

| 2. Integration of technology in care | 1.2.1. Digital technologies allowed physicians to extend their reach, especially valuable in rural areas. | [22] | |

| 1.2.2. Leveraging telemedicine technologies, like remote monitoring and consultations, reduces geographical barriers and clinical uncertainty. | [23] | ||

| 1.2.3. Remote Patient Monitoring enhances economies of scale, reduces costs by expanding patient eligibility, and should be closely monitored for cost efficiency. | [24] | ||

| 1.2.4. Virtual care faced limitations in physical assessments like musculoskeletal and neurologic exams, leading to in-person waitlists. | [25] | ||

| 1.2.5. Telehealth hybrid models for paediatric physiotherapy showed no significant increase in adverse events and high acceptability. | [21] | ||

| 1.2.6. Video-based appointments provide a greater sense of confidence with the examination and care plan than telephone visits. | [25] | ||

| 1.2.7. Using vital sign remote patient monitoring in the HITH model could align with standard practice of checking vital signs every 4-8 h, allowing for safe care of moderate-acuity patients who usually aren’t included in HITH. Whitehead and Conley [13] specifically identified this as a mechanism to expand patient eligibility while maintaining safety standards | [24] | ||

| 1.2.8. Having a fully integrated electronic medical record system that connects inpatient, outpatient, and home care data can significantly enhance care coordination and information sharing among all providers. | [20] | ||

| 3. Impact of home care models on patient outcomes | 1.3.1. The HITH model can lower the need for emergency readmissions by offering post-discharge restorative care. | [19] | |

| 1.3.2. The HITH model has been shown to reduce the length of stay compared to traditional hospital care, particularly in stroke rehabilitation, and provides flexibility to adapt to different patient needs and health crises. | [26] | ||

| 1.3.3. Pre-discharge planning combined with telephone-based support reduced readmissions, supporting dementia caregivers. | [27] | ||

| 1.3.4. Shifting focus from “readiness for discharge” to “readiness for home care” helped improve transitions for dementia patients. | [27] | ||

| 2. Staffing, Training, and Team Dynamics | 1. Training and specialized knowledge | 2.1.1. A central point person is necessary for coordinating resources and triaging patient calls in complex care scenarios. | [28] |

| 2.1.2. Staffing for home-based care should prioritize providers with experience in caring for medically vulnerable populations. | [28] | ||

| 2.1.3. Clinicians experienced in home-based care are more likely to identify suitable patients compared to hospital ward clinicians. | [23] | ||

| 2.1.4. Centralizing training at regional hubs while managing routine follow-ups locally can enhance care quality. | [14] | ||

| 2.1.5. The lead clinician should be a consultant respiratory physician, supported by trainee junior medical staff. | [29] | ||

| 2.1.6. The home care team should be led by a specialist respiratory nurse, physiotherapist, or appropriately qualified health professional. | [29] | ||

| 2. Care coordination and multidisciplinary teams | 2.2.1. Daily “huddles” and case reviews keep multidisciplinary teams engaged and responsive to patient needs. | [30] | |

| 2.2.2. Proactive review of patients in hospital wards and regular communication with clinicians facilitated appropriate referrals for home-based care. This approach helps identify the right candidates for home-based treatments effectively. | [23] | ||

| 2.2.3. Having a fully integrated electronic medical record system that connects inpatient, outpatient, and home care data can significantly enhance care coordination and information sharing among all providers. | [20] | ||

| 2.2.4. Using an in-house home care team familiar with patient needs and experienced in collaborating with physicians can lead to better care coordination and lower complication rates. | [20] | ||

| 3. Governance and Financial Sustainability | 1. Governance structures | 3.1.1. Formalized governance structures ensure transparent accountability and effective process management. | [14] |

| 3.1.2. Collaboration between management governance (focused on business compliance) and clinical governance (focused on patient care) is essential for ensuring patient-centred decisions. | [14] | ||

| 3.1.3. A centralized command centre allowed for consistent patient volumes and outcomes across geographically separate regions. Paulson et al. [8] demonstrated this in their hybrid hospital-at-home model implemented across two different geographical regions using a single command centre, achieving consistent outcomes in both locations. | [19] | ||

| 3.1.4. After recruitment to HITH, clinical responsibility and out-of-hours cover should be undertaken by the acute trust. | [29] | ||

| 3.1.5. When the patient is discharged from HITH program, clinical responsibility should be formally transferred back to primary care either by fax or by email. | [29] | ||

| 2. Financial sustainability | 3.2.1. Balancing long-term savings with the immediate costs of expanding home-based acute care services was challenging, requiring financial planning. | [28] | |

| 3.2.2. Securing reimbursement for services like nurse practitioner visits helped mitigate cash flow challenges. | [28] | ||

| 3.2.3. Early-discharge models might be easier to develop and implement and provide higher patient throughput. However, hospital substitution models offer more significant cost savings and reduced iatrogenic events. | [20] | ||

| 3. Cross-sector collaboration | 3.3.1. Cross-sector collaboration between hospitals, nursing homes, and community providers fostered care continuity, enhancing long-term care models. | [31] | |

| 3.3.2. Partnership with community paramedicine allows for faster response times and provides us with more treatment tools. | [28] | ||

| 3.3.3. Establishing a solid relationship with external clinical partners is crucial. Clearly define expectations during the contracting phase and conduct regular check-ins to resolve any emerging issues. | [32] | ||

| 4. Patient Selection and Safety | 1. Rigorous patient selection | 4.1.1. Effective patient selection for home-based care reduces emergency readmissions. | [19] |

| 4.1.2. Using validated and explicit criteria for patient selection helps in managing patient risk, reducing complications, and potentially decreasing the overall length of stay at home. | [20] | ||

| 4.1.3. Rigorous patient selection and restorative care options enabled the program to achieve significantly better outcomes. | [19] | ||

| 4.1.4. Providing home care to a patient depends on factors such as the requirement for fixed hospital equipment, comprehensive environmental safety assessment of the living environment (including physical safety features, utility availability, infection control capability, and emergency access), and the readiness of involved parties (family members, the family doctor, and the hospital team leader) to take on additional responsibilities | [33] | ||

| 4.1.5. Oncology toxicities issues such as pain, nausea and vomiting, neutropenic fever, and infections can be effectively managed with acute-level care at home. An escalation protocol should employ to return patients to the emergency department or ambulatory care centre if they could not be stabilized at home. | [32] |

| Study | HITH Program Context | Primary Findings Reported | Lessons Extracted (Code) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paulson et al. (2023) [19] | Hybrid virtual/in-person acute care across two regions | Centralized command center maintained consistent outcomes across geographically separate hospitals; effective patient selection reduced ED readmissions | 3.1.3, 4.1.1 |

| Mader et al. (2008) [20] | Hospital substitution for CAP, CHF, COPD, cellulitis | Admission easier from inpatient beds vs. ED; substitution models offer greater cost savings than early discharge; validated patient criteria reduced LOS | 1.1.3, 3.2.3, 4.1.2 |

| Benz et al. (2023) [21] | Pediatric telehealth physiotherapy for CF | Hybrid model increased staff scheduling flexibility; reduced travel time during peak traffic | 1.1.4, 1.2.4 |

| Nair et al. (2023) [22] | Virtual ED fast track | Digital technologies extended physician reach, especially valuable in rural areas | 1.2.1 |

| Lim et al. (2024) [23] | General acute HITH | Active ward review and clinician communication improved patient identification; remote monitoring reduced geographical barriers | 1.2.2, 4.1.3 |

| Whitehead & Conley (2023) [24] | Remote patient monitoring overview | Technology integration enhances HITH outcomes and enables program expansion | 1.2.3, 1.3.1 |

| Lopez et al. (2021) [25] | Virtual cancer rehabilitation during COVID-19 | Rapid technology adaptation maintained service continuity; virtual delivery achieved comparable outcomes | 1.3.3, 2.2.2 |

| Inzitari et al. (2021) [26] | Geriatric HITH during COVID-19 | At-home model reduced LOS in stroke rehabilitation; flexibility to adapt to health crises | 1.3.2 |

| Toles et al. (2023) [27] | Transitional care for dementia patients | Shifting focus from ‘discharge readiness’ to ‘home readiness’ improved transitions; caregiver engagement critical | 1.3.4, 2.2.4 |

| Fulton et al. (2022) [28] | Comprehensive in-home care for complex needs | Central coordinator essential for resource management; partnership with paramedicine improved response times; balancing immediate costs with long-term savings challenging | 2.1.1, 3.2.1, 3.3.2 |

| Marshall et al. (2015) [14] | Home hemodialysis | Formalized governance ensured transparency and accountability; centralized training with local follow-up enhanced quality; management-clinical governance collaboration improved decisions | 2.1.4, 3.1.1, 3.1.2 |

| BTS Guidelines (2007) [29] | COPD hospital-at-home | Specialist nurse/physiotherapist leadership required; formal transfer of clinical responsibility at discharge; acute trust maintains out-of-hours responsibility | 2.1.6, 2.2.1, 2.2.3 |

| Franzosa et al. (2021) [30] | Home-based primary care during COVID-19 | Pandemic accelerated technology adoption; interprofessional coordination essential for complex patients | 2.1.2, 2.2.5 |

| Wong et al. (2022) [31] | Collaborative nursing home care during COVID-19 | Cross-sector collaboration (hospitals, nursing homes, community) ensured care continuity | 3.3.1 |

| Titchener et al. (2021) [32] | Oncology hospital-at-home | Clearly defined partner expectations critical; regular check-ins addressed emerging issues; oncology toxicities manageable at home with escalation protocols | 3.3.3, 4.1.5 |

| Lightwood et al. (1957) [33] | Pediatric home care trial | Early evidence of home care feasibility for pediatric populations | 1.1.1, 1.1.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Purarjomandlangrudi, A.; Ghapanchi, A.H.; Stevens, J.; Ahmadi Eftekhari, N.; Barnes, K. Lessons Learned from Governance and Management of Virtual Hospital Initiatives: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120451

Purarjomandlangrudi A, Ghapanchi AH, Stevens J, Ahmadi Eftekhari N, Barnes K. Lessons Learned from Governance and Management of Virtual Hospital Initiatives: A Systematic Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):451. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120451

Chicago/Turabian StylePurarjomandlangrudi, Afrooz, Amir Hossein Ghapanchi, Josephine Stevens, Navid Ahmadi Eftekhari, and Kirsty Barnes. 2025. "Lessons Learned from Governance and Management of Virtual Hospital Initiatives: A Systematic Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120451

APA StylePurarjomandlangrudi, A., Ghapanchi, A. H., Stevens, J., Ahmadi Eftekhari, N., & Barnes, K. (2025). Lessons Learned from Governance and Management of Virtual Hospital Initiatives: A Systematic Review. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 451. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120451