Effects of a Cluster Randomized Educational Intervention on Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Women’s Trafficking Among Undergraduate Nursing Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

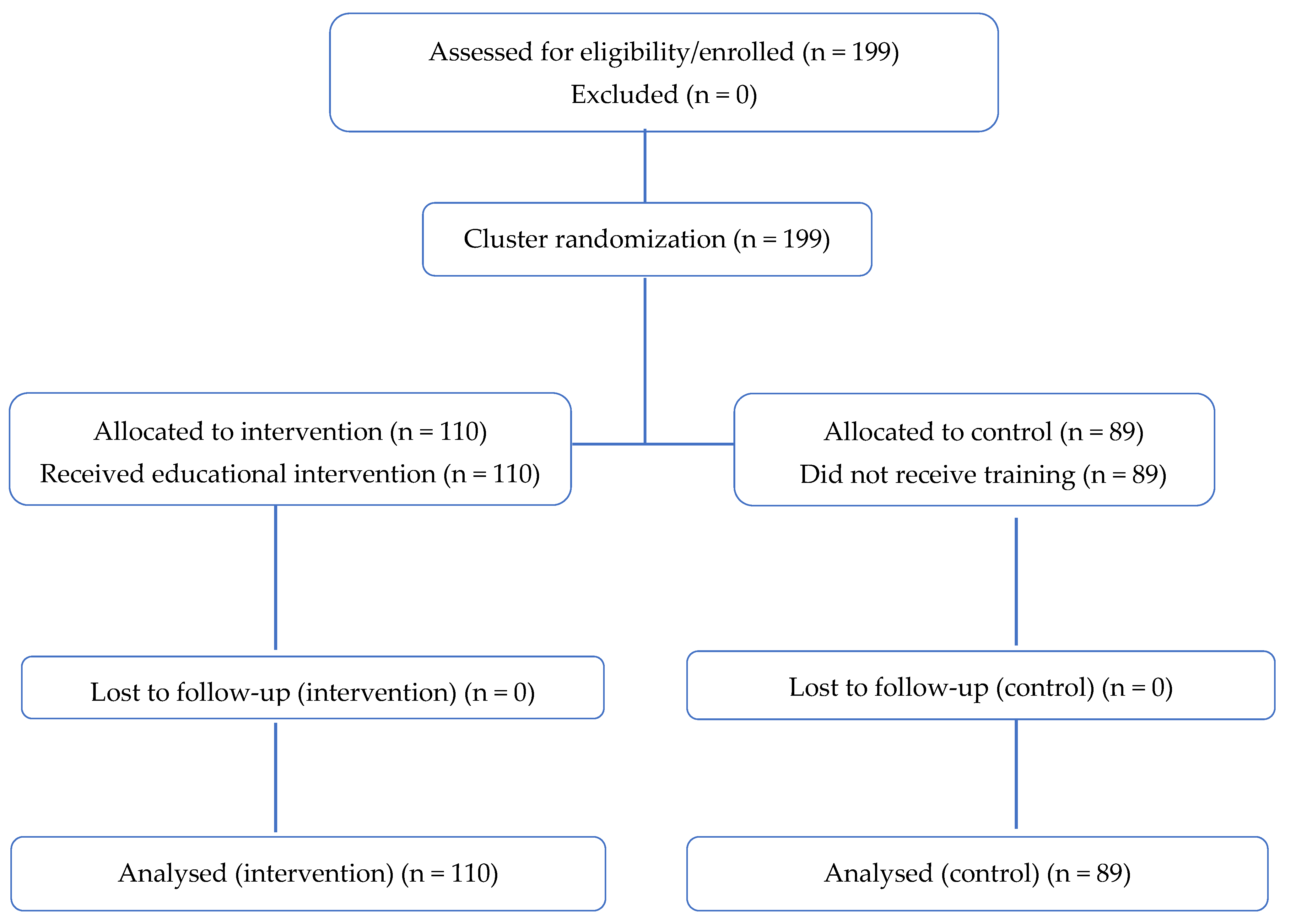

2.1. Design

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Measures

- “Have you ever met a victim of sex trafficking?” (Yes/No)

- “Are you familiar with statistics on human trafficking?” (Yes/No)

- “Have you received any training on how to identify victims of human trafficking?” (Yes/No)

- “Do you consider training on human trafficking for the purpose of sexual exploitation to be practical for your professional development?” (Yes/No)

- “How would you describe your current knowledge regarding the identification of individuals who may be victims of sex trafficking?” (Very low/Below average/Average/Above average/Very high)

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Intervention

- The session started with an activity designed to promote awareness and sensitization, through the screening of the short film Miente (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mqSLUTWmvfo, accessed on 27 May 2024), which lasted 15 min. After the screening, students were asked what they imagined to be the life of a female victim of sex trafficking.

- Secondly, the instructor delivered a presentation on the concepts of human trafficking and other forms of exploitation. To this end, the Palermo Protocol was introduced as a key instrument of international legislation, and Article 177 bis of the Spanish Criminal Code was discussed to illustrate how human trafficking is legally defined as a criminal offense in Spain. Finally, the Spanish covenant for the elimination of violence against women (Pacto de Estado contra la Violencia de Género) was explained, as well as the different types of violence experienced by victims. Intervention continued with the differentiation between migrant smuggling and trafficking. Thirdly, human trafficking was explained as a process of recruitment in an originating country, smuggling and transfer of individuals for their exploitation. Instructors explained to the students how criminal networks and mafias operate to recruit women in their countries of origin, as well as the emerging methods of recruitment in contexts such as armed conflicts, delocalized prostitution, and domestic trafficking.

- After this, an activity of awareness and sensitization was conducted through the projection of the 15 min short film Puta Vida (https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x4xrdnp, accessed on 27 May 2024). Students were then asked about the impact of prostitution and trafficking on women’s health.

- The following 30 min section addressed the healthcare response to trafficking for sexual exploitation, with a focus on the standardized protocol used within the Spanish National Health System to address gender-based violence. The prevention of trafficking for purposes of sexual exploitation within the health sector and the importance of the response of health professionals towards trafficking were particularly highlighted. Detection of victims, the impact and consequences of trafficking on women’s health, as the intervention of health professionals in case of suspicion of a potential case were explained according to three different scenarios: (a) the victim is not aware of her situation; (b) the victim is aware of her situation; (c) the victim is aware of her situation and declares she is willing to receive support. In addition, participants were instructed on how to report a potential case, and on which are the resources available and the victim’s rights.

- Finally, a group debate was conducted to discuss the causes of trafficking of women for sexual exploitation and the possible solutions to abolish this crime.

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CRCT | Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial |

| df | Degrees of Freedom |

| EC | Ethics Committee |

| HCP | Health Care Professionals |

| HT | Human Trafficking |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| ST | Sex Trafficking |

| US | University of Seville |

| χ2 | Chi-Square |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| STAS | Sex Trafficking Attitudes Scale |

| ICMJE | International Committee of Medical Journal Editors |

| EATS | Scale of Attitudes towards Sex Trafficking of Women and Girls |

| CONSORT | Consolitadated Standards of Reporting Trials |

References

- Sanchez, R.V.; Speck, P.M.; Patrician, P.A. Trauma coercive bonding. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2019, 46, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2024; United Nations: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.unodc.org/ropan/es/Noticias/2024_11diciembre_reporte_global_trata_2024.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Centro de Inteligencia contra el Terrorismo y el Crimen Organizado (CITCO). Balance Estadístico 2018–2022: Trata y Explotación de Seres Humanos en España; Ministerio del Interior: Madrid, Spain, 2023. Available online: https://www.interior.gob.es/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). ILO Global Estimate of Forced Labour: Results and Methodology; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://respect.international/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Cobo Bedia, R. La Prostitución en el Corazón del Capitalismo; Catarata: Madrid, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maus, E. Trata de personas y derechos humanos. Cotidiano 2018, 209, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ranea, B. Feminización de la Supervivencia y Prostitución Ocasional; Federación de Mujeres Progresistas: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://bit.ly/3tHcShp (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Macias-Konstantopoulos, W. Human trafficking: The role of medicine. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lederer, L.J.; Wetzel, C.A. The health consequences of sex trafficking. Ann. Health Law 2014, 23, 61–91. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.L.; Chisolm-Straker, M.; Duke, G.; Stoklosa, H. Recommendations for healthcare provider education programs. J. Hum. Traff. 2019, 6, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederson, A.C.; Gerassi, L.B. Healthcare providers’ perspectives. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Dimitrova, S.; Howard, L.M.; Dewey, M.; Zimmerman, C.; Oram, S. Human trafficking and health. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, S.O.; Hughes, D.R. Clinical nurse leaders address a call to action on human trafficking. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2020, 35, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAmis, N.E.; Mirabella, A.C.; McCarthy, E.M.; Cama, C.A.; Fogarasi, M.C.; Thomas, L.A.; Feinn, R.S.; Rivera-Godreau, I. Assessing healthcare provider knowledge. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264338. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.R.; Furr, S.B. Integration of human trafficking education within nursing curricula. J. Prof. Nurs. 2023, 47, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Geynisman-Tan, J.; Hofer, S.; Anderson, E.; Caravan, S.; Titchen, K. The impact of human trafficking training. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2021, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, C.; Dickins, K.; Stoklosa, H. Training US healthcare professionals. Med. Educ. Online 2017, 22, 1267980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eger, H.; Chacko, S.; El-Gamal, S.; Gerlinger, T.; Kaasch, A.; Meudec, M.; Munshi, S.; Naghipour, A.; Rhule, E.; Sandhya, Y.K.; et al. Towards a feminist global health policy: Power, intersectionality, and transformation. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2024, 4, e0002959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, R.M. Human trafficking education for nurse practitioners. Nurs. Educ. Today 2018, 61, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerassi, L.B.; Nichols, A.J. Social Work Education that Addresses Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation: An Intersectional, Anti-Oppressive Practice Framework. Anti-Traffick. Rev. 2021, 17, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaño, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Theory of reasoned action. In Health Behavior: Theory, Research and Practice; Glanz, K., Rimer, B.K., Viswanath, K., Eds.; Jossey-Bass/Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, C.; McAllister, M.; Batty, C.; Vanderburg, R.; Cattoni, J. Using films in nursing educator workshops. Educ. Action Res. 2023, 32, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Villoria, C.; Picornell-Lucas, A.; Patino-Alonso, C. Cultural adaptation and validation. Violence Against Women 2022, 28, 3242–3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisolm-Straker, M.; Baldwin, S.; Gaïgbé-Togbé, B.; Ndukwe, N.; Johnson, P.N.; Richardson, L.D. Health care and human trafficking: We are seeing the unseen. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2016, 27, 1220–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.E.; Lineer, M.M.; Melzer-Lange, M.; Simpson, P.; Nugent, M.; Rabbitt, A. Medical providers’ understanding of sex trafficking and their experience with at-risk patients. Pediatrics 2015, 135, e895–e902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, R.; Alpert, E.; Purcell, G.; Macias-Konstantopoulos, W.; McGahan, A.; Cafferty, E.; Eckardt, M.; Conn, K.; Cappetta, K.; Burke, T. Human trafficking: Review of educational resources for health professionals. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoklosa, H.; Baldwin, S. Health professional education on trafficking. Lancet 2017, 390, 1641–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, D.; Cornell, G.; Bono-Neri, F. Outcomes of Simulation-Based Education on Prelicensure Nursing Students’ Preparedness in Identifying a Victim of Human Trafficking. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, E.J.F.M. Long-term retention of basic science knowledge: A review study. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havig, K.; Mahapatra, N. Health-care providers’ knowledge of human trafficking. J. Hum. Traff. 2020, 7, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono-Neri, F.; Toney-Butler, T.J. Nursing Students’ Knowledge of and Exposure to Human Trafficking Content in Undergraduate Curricula. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 125, 105799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.C.; Hong, J.; Leung, P.; Yin, P.; Stewart, D.E. Canadian medical students’ awareness. Educ. Health 2011, 24, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, P.; Steele, S. UK medical education on human trafficking: Assessing uptake of the opportunity to shape awareness, safeguarding and referral in the curriculum. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, R.; Recknor, F.; Bruder, R.; Quayyum, F.; Montemurro, F.; Mont, J.D. Health Care Providers Describe the Education They Need to Care for Sex-Trafficked Patients. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastor-Moreno, G.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Sordo, L. Barreras y Propuestas para el Abordaje Sanitario de la Trata con Fines de Explotación Sexual. Gac. Sanit. 2023, 37, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chisolm-Straker, M.; Richardson, L.D.; Cossio, T. Combating slavery in the 21st century: The role of emergency medicine. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2012, 23, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ 2025, 388, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sociodemographic Factors | Control Group (n = 89) n (%) | Experimental Group (n = 110) n (%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.19 | |||

| Female | 79 (88.8) | 90 (81.1) | ||

| Male | 10 (11.2) | 21 (18.9) | ||

| Age | 0.08 | |||

| Under 20 years old | 47 (52.8) | 39 (35.1) | ||

| 20–25 years | 38 (42.7) | 62 (55.9) | ||

| 26–30 years | 1 (1.1) | 2 (1.8) | ||

| Over 30 years old | 3 (3.4) | 8 (7.2) | ||

| Previous training on human trafficking (yes) | 24 (27) | 28 (25.2) | 0.937 | |

| Are you familiar with human trafficking statistics? (yes) | 2 (2.2) | 9 (8.1) | 0.116 | |

| Would you benefit from training on human trafficking? (yes) | 89 (100) | 110 (100) | - | |

| Items | Level | Control n (%) | Experimental Pre n (%) | Experimental Post n (%) | p (C-Pre) | p (Pre–Post) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge to identify a victim of sex trafficking | Very low | 8 (9) | 10 (9) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 19 (21.3) a | 41 (36.9) ab | 4 (3.6) b | |||

| Average | 55 (61.8) b | 45 (40.5) bb | 21 (19.1) b | |||

| Above average | 6 (6.7) | 15 (13.5) b | 75 (68.2) b | |||

| Very high | 1 (1.1) | 0 (8.2) b | 9 (8.2) b | |||

| Knowledge of your role, as future health professional, in the identification of victims of trafficking and your response | Very low | 9 (10.1) | 12(10.8) b | 1(0.9) b | 0.596 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 24 (27) | 39 (35.1) b | 3 (2.7) b | |||

| Average | 42 (47.2) | 40 (36) | 29 (26.4) | |||

| Above average | 10 (11.2) | 15 (13.5) b | 64 (58.2) b | |||

| Very high | 4 (4.5) | 5 (4.5) a | 13 (11.8) a | |||

| Knowledge on the indicators or red flags of sex trafficking | Very low | 8 (9) | 11(9.9) b | 1(0.9) b | 0.767 | 0.001 |

| Below average | 25 (28.1) | 34 (30.6) b | 3 (2.7) b | |||

| Average | 45 (50.6) | 48 (43.2) b | 22 (20) b | |||

| Above average | 11 (12.4) | 17 (15.3) b | 68 (61.8) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) b | 16 (14.5) b | |||

| Knowledge on the practices in which sex trafficking victims are usually involved | Very low | 9 (10.1) | 16 (14.4) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.494 | 0.001 |

| Below average | 24 (27) | 36 (32.4) b | 3 (2.7) b | |||

| Average | 47 (52.8) | 47 (42.3) b | 29 (26.4) b | |||

| Above average | 9 (10.1) | 12 (10.8) b | 60 (54.5) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) a | 17 (15.5) a | |||

| Knowledge on which are the right questions to identify a victim of sex trafficking | Very low | 12 (13.5) | 17 (15.3) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.726 | 0.001 |

| Below average | 31 (34.8) | 43 (38.7) b | 6 (5.5) b | |||

| Average | 39 (43.8) | 46 (41.4) a | 30 (27.3) a | |||

| Above average | 7 (7.9) | 5 (4.5) b | 62 (56.4) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) b | 11 (10) b | |||

| Knowledge on what are the major demands of victims of sex trafficking | Very low | 14 (15.7) | 16 (14.4) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.875 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 35 (39.3) | 42 (37.8) b | 4 (3.6) b | |||

| Average | 36 (40.4) | 45 (40.5) | 33 (30) | |||

| Above average | 4 (4.5) | 8 (7.2) b | 60 (54.5) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) b | 12 (10.9) b | |||

| Knowledge on what are the major health problems of the victims of sex trafficking | Very low | 5 (5.6) | 8 (7.2) a | 1 (0.9) a | 0.702 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 17 (19.1) | 22 (19.8) b | 2 (1.8) b | |||

| Average | 44 (49.4) | 55 (49.5) b | 23 (20.9) b | |||

| Above average | 23 (25.8) | 24 (21.6) b | 65 (59.1) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 2 (1.8) b | 19 (17.3) b | |||

| Knowledge on the documentation available in the current health policy when we suspect someone is a victim of sex trafficking | Very low | 25 (28.1) | 28 (25.2) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.557 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 30 (33.7) | 48 (43.2) b | 8 (7.3) b | |||

| Average | 27 (30.3) | 29 (26.1) | 36 (32.7) | |||

| Above average | 7 (7.9) | 6 (5.4) b | 56 (50.9) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) b | 9 (8.2) b | |||

| Knowledge on the local and/or national support regarding sex trafficking | Very low | 18 (20.2) | 26 (23.4) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.285 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 38 (42.7) | 35 (31.5) b | 6 (5.5) b | |||

| Average | 27 (30.3) | 45 (40.5) | 37 (33.6) | |||

| Above average | 6 (6.7) | 5 (4.5) b | 54 (49.1) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) b | 12 (10.9) b | |||

| Knowledge on the local and/or national policies in relation to sex trafficking | Very low | 24 (27) | 29 (26.1) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.605 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 40 (44.9) | 44 (39.6) b | 7 (6.4) b | |||

| Average | 22 (24.7) | 36 (32.4) | 48 (43.6) | |||

| Above average | 3 (3.4) | 2 (1.8) b | 47 (42.7) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) b | 7 (6.4) b | |||

| Knowledge on the resources and/or appropriate references to advise a victim of sex trafficking | Very low | 19 (21.3) | 24 (21.6) b | 1 (0.9) b | 0.400 | <0.001 |

| Below average | 35(39.3) | 33 (29.7) b | 5 (4.5) b | |||

| Average | 29 (32.6) | 48 (43.2) b | 28 (25.5) b | |||

| Above average | 6 (6.7) | 6 (5.4) b | 68 (61.8) b | |||

| Very high | 0 (0) | 0 (0) b | 8 (7.3) b |

| Items | Pretest | Post-Test | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Sex Trafficking Attitudes Scale (STAS) | 119.57 | 9.00 | 128.24 | 10.61 | <0.0001 |

| Possibility of escaping sex trafficking | 25.71 | 3.80 | 25.71 | 4.10 | 0.7832 |

| Empathetic reactions towards sex trafficking | 28.51 | 2.18 | 29.26 | 1.42 | 0.0011 |

| Attitudes of support towards survivors | 10.95 | 3.61 | 14.58 | 3.72 | <0.0001 |

| Awareness of sex trafficking | 15.63 | 4.16 | 17.06 | 4.57 | 0.0155 |

| Knowledge on sex trafficking | 22.21 | 2.85 | 22.98 | 1.85 | 0.0656 |

| Efficacy to reduce sex trafficking | 16.57 | 3.47 | 18.64 | 3.34 | <0.0001 |

| Control (n = 89) | Post Intervention (n = 110) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p Value |

| Sex Trafficking Attitudes Scale (STAS) | 118.47 (11.02) | 128.24 (10.61) | p < 0.001 |

| Possibility of escaping sex trafficking | 25.57 (3.35) | 25.71 (4.10) | p = 0.801 |

| Empathetic reactions towards sex trafficking | 27.23 (3.57) | 29.26 (1.42) | p < 0.001 |

| Attitudes of support towards survivors | 12.14 (3.60) | 14.58 (3.72) | p < 0.001 |

| Awareness of sex trafficking | 15.20 (4.38) | 17.06 (4.57) | p = 0.004 |

| Knowledge on sex trafficking | 22.09 (3.74) | 22.98 (1.85) | p = 0.042 |

| Efficacy to reduce sex trafficking | 16.25 (3.36) | 18.64 (3.34) | p < 0.001 |

| Control Pretest (n = 89) | Follow-Up Control (n = 81) | Intervention Pretest (n = 111) | Intervention Posttest (n = 110) | Follow-Up Intervention (n = 107) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Items | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p Value |

| Sex Trafficking Attitudes Scale (STAS) | 118.47 (11.02) | 113.63 (12.85) | 119.57 (9) | 128.24 (10.61) | 116.89 (14.10) | p < 0.001 |

| Possibility of scaping sex trafficking | 25.57 (3.35) | 25.44 (3.4) | 25.71(3.8) | 25.71 (4.10) | 25.54(4.9) | p = 0.625 |

| Empathetic reactions towards sex trafficking | 27.23 (3.57) | 26.43 (3.78) | 28.50 (2.18) | 29.26 (1.42) | 27.51 (4.1) | p < 0.001 |

| Attitudes of support towards survivors | 12.14 (3.60) | 12.07(3.56) | 10.95 (3,61) | 14.58 (3.72) | 11.37 (3.87) | p < 0.001 |

| Awareness of sex trafficking | 15.20 (4.38) | 14.33 (5.47) | 15.63 (4.16) | 17.06 (4.57) | 15.47 (4.76) | p < 0.001 |

| Knowledge on sex trafficking | 22.09 (3.74) | 20.94 (4.33) | 22.21 (2.85) | 22.98 (1.85) | 21.09 (4.09) | p < 0.001 |

| Efficacy to reduce sex trafficking | 16.25 (3.36) | 14.41 (4.23) | 16.57 (3.47) | 18.64 (3.34) | 15.90 (3.86) | p < 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ramírez-Zambrana, C.; Leon-Larios, F.; Ruiz-Ferron, C.; Casado-Mejía, R. Effects of a Cluster Randomized Educational Intervention on Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Women’s Trafficking Among Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120450

Ramírez-Zambrana C, Leon-Larios F, Ruiz-Ferron C, Casado-Mejía R. Effects of a Cluster Randomized Educational Intervention on Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Women’s Trafficking Among Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120450

Chicago/Turabian StyleRamírez-Zambrana, Cristina, Fátima Leon-Larios, Cecilia Ruiz-Ferron, and Rosa Casado-Mejía. 2025. "Effects of a Cluster Randomized Educational Intervention on Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Women’s Trafficking Among Undergraduate Nursing Students" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120450

APA StyleRamírez-Zambrana, C., Leon-Larios, F., Ruiz-Ferron, C., & Casado-Mejía, R. (2025). Effects of a Cluster Randomized Educational Intervention on Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Women’s Trafficking Among Undergraduate Nursing Students. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 450. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120450