An Action Plan to Facilitate the Transfer of Pain Management Competencies Among Nurses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aim and Objectives

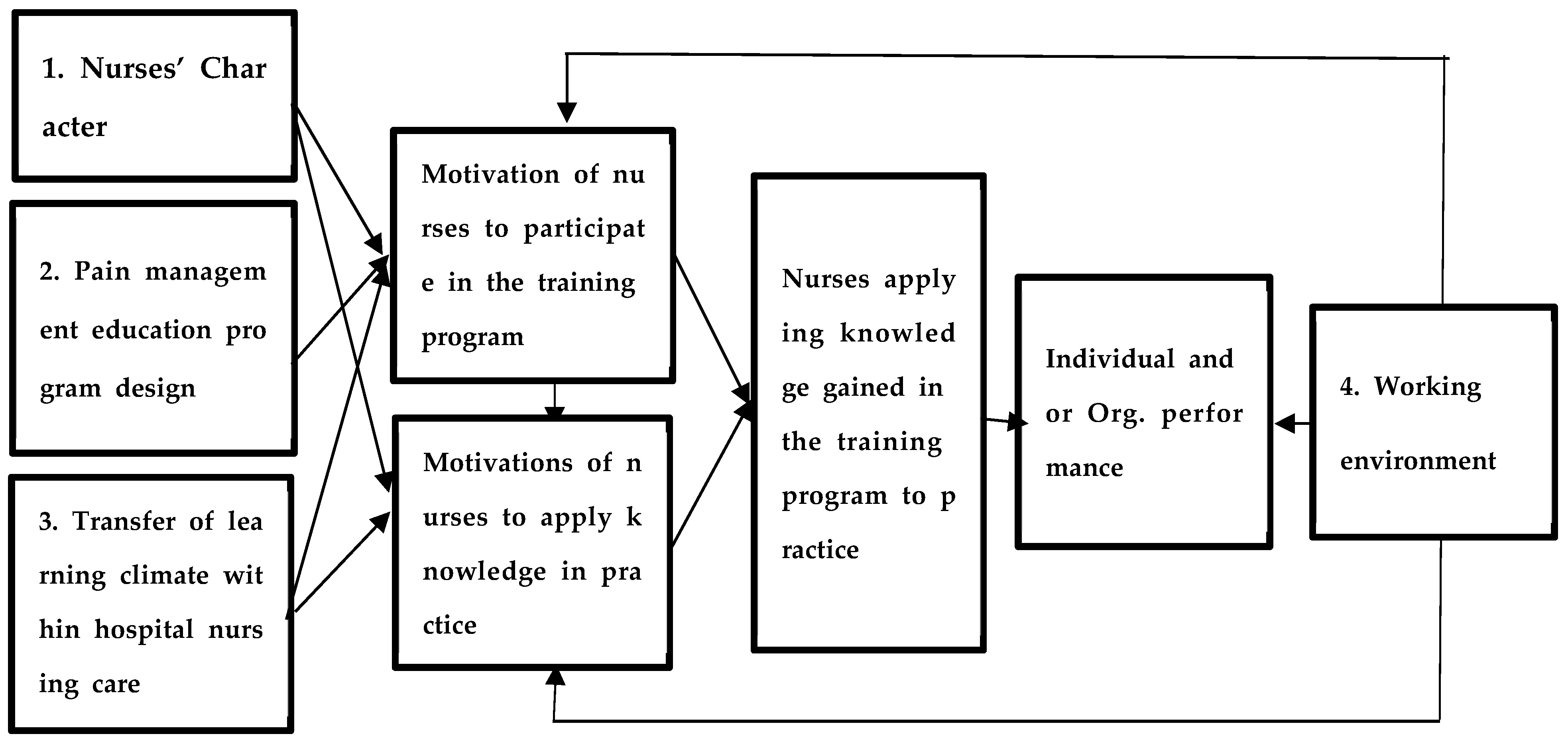

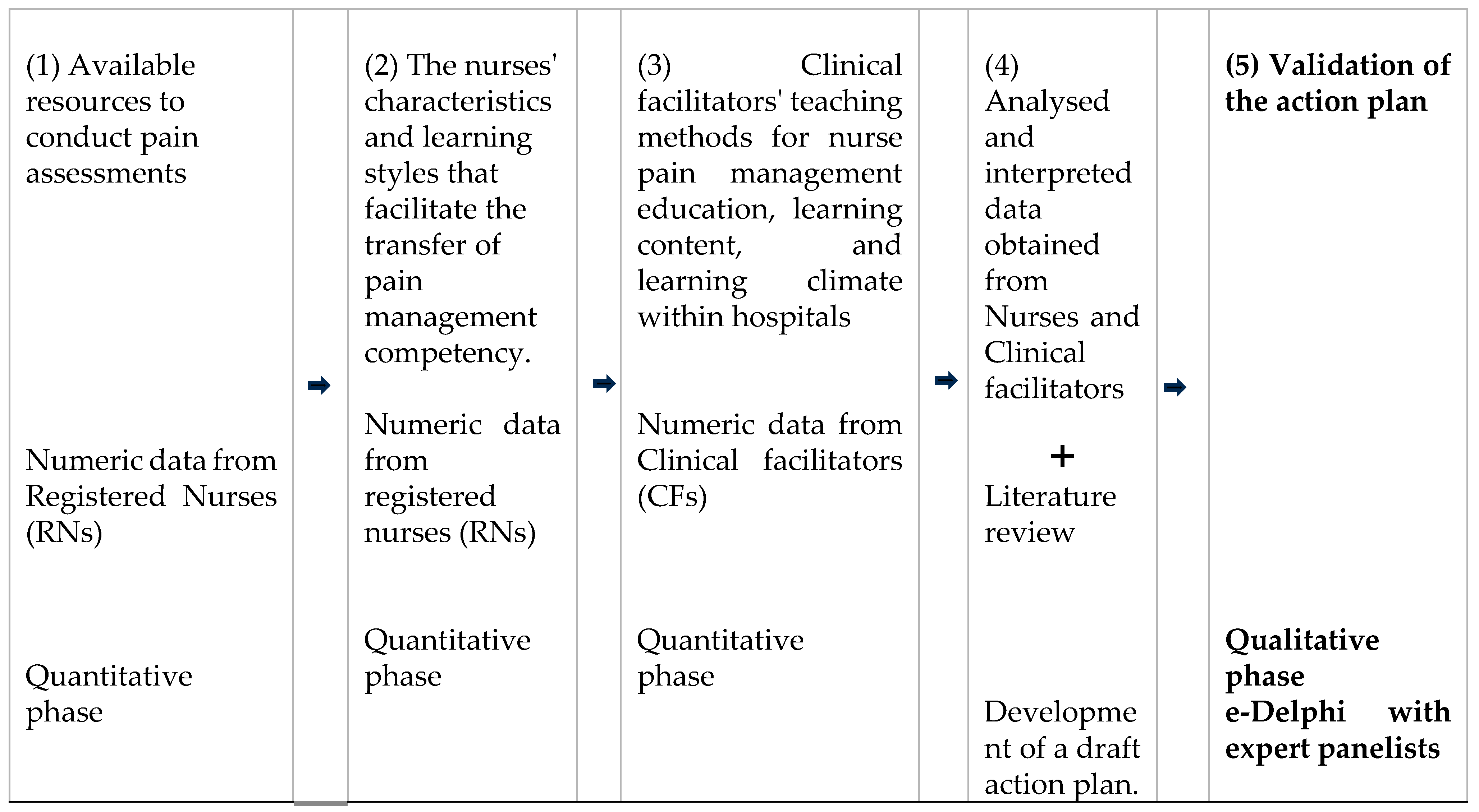

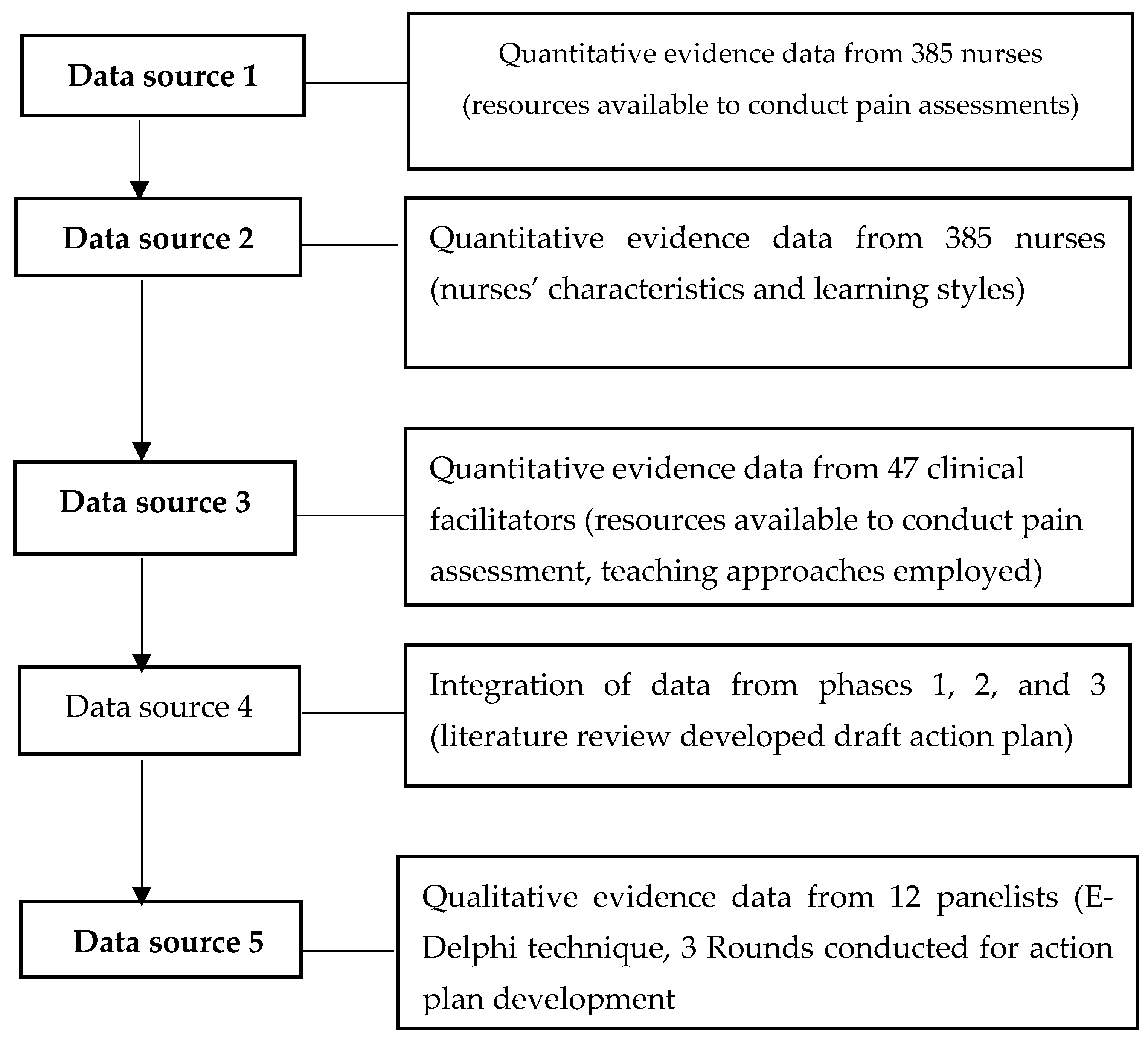

2.2. Design

2.3. Setting

2.4. Population and Sampling

- Attendance at a pain management workshop within the last three years.

- Receipt of in-service pain management training within the past year.

- Training in pain management by clinical facilitators for nurses in the five nursing care divisions.

- Comfort with being interviewed in English.

- Demonstrated enthusiasm for pain management.

- Registered nurses who have had at least one pain management training course within the past two years.

- Registered nurses who received pain management in-service training within the last year.

- Clinical facilitators who are responsible for instructing nurses in pain management within the nursing care divisions.

- Willing to participate in a minimum of three Delphi rounds.

2.5. Ethical Considerations and Data Collection

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Validity and Reliability Pre-Testing of the Delphi Validation Tool

2.8. Trustworthiness

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biographic Data

3.2. The Final Validated Action Plan

4. Discussion

4.1. Motivating Nurses to Further Their Studies

4.2. Pain Management Tools to Be Accessible to the Nursing Team in Every Clinical Area

4.3. Developing a Short, Practice-Based Pain Management Training Program

4.4. Developing a Short Pain Management Program for All Learners

4.5. Incorporating Different Teaching Approaches in Pain Management Training

4.6. Developing Strategies to Motivate Nurses to Attend Short Training Programs

4.7. Motivating Nurses to Apply Their Training to Practice

4.8. Implications

4.9. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CFs | Clinical Facilitators |

| CNE | Center of Nursing Education |

| CREDES | Conducting and reporting DELphi Studies |

| CRIES | Crying, Required oxygen, Increased vital signs, Expression, Sleeplessness |

| CSPMS | Core Standards for Pain Management Service |

| IASP | International Association for the Study of Pain |

| KAIMRC | King Abdullah International Medical Research Committee |

| MNGHA | Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs |

| PQRST | Provocation and palliation symptoms, Quality of pain, Region and radiation of pain, Severity of pain, and Timing |

| RNs | Registered nurses |

| SLR | Self-regulated learning theory |

| SMART | Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic, and Time-bound goals |

References

- Nabizadeh-Gharghozar, Z.; Alavi, N.M.; Ajorpaz, N.M. Clinical competence in nursing: A hybrid concept analysis. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 97, 104728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, S. Learning in the Workplace: Strategies for Effective Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wubalem, A.Y. Assessing learning transfer and constraining issues in EAP writing practices. Asian-Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 2021, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.H.; Johnson, J.; Heyhoe, J.; Watt, I.; Anderson, K.; O’Connor, D.B. Exploring the impact of primary care physician burnout and well-being on patient care: A focus group study. J. Patient Saf. 2020, 16, e278–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldland, E.; Botti, M.; Hutchinson, A.M.; Redley, B. A framework of nurses’ responsibilities for quality healthcare—Exploration of content validity. Collegian 2020, 27, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Vogelsang, A.C.; Swenne, C.L.; Gustafsson, B.Å.; Falk Brynhildsen, K. Operating theatre nurse specialist competence to ensure patient safety in the operating theatre: A discursive paper. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, K.; Coyne, P.J.; Ely, E.; Gélinas, C.; Manworren, R.C. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: Clinical practice recommendations in support of the ASPMN 2019 position statement. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2019, 20, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, O.M.; Al-Bashaireh, A.M.; Khafajeh, R.; Alqudah, O. Neonatal palliative care: Assessing the nurses educational needs for terminally ill patients. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0280081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, J.; Manser, T. Nurses’ knowledge, behavior and compliance concerning infection prevention in nursing homes: Individual and organizational influences. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sayaghi, K.M.; Fadlalmola, H.A.; Aljohani, W.A.; Alenezi, A.M.; Aljohani, D.T.; Aljohani, T.A.; Alsaleh, S.A.; Aljohani, K.A.; Aljohani, M.S.; Alzahrani, N.S.; et al. Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding pain assessment and management in Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarkandi, O.A. The factors affecting nurses’ assessments toward pain management in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2021, 15, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, K.; Higgins, I.; Chan, S. Nurses’ knowledge and attitude toward pediatric pain management: A cross-sectional study. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2019, 20, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, E.; Boud, D.; Henderson, M. Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, T.E.; Lee, S.Y. College students’ experience of emergency remote teaching due to COVID-19. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, P.; Darcy, D.P. Learning transfer: The views of practitioners in Ireland. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2011, 15, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botma, Y.; Van Rensburg, G.H.; Coetzee, I.M.; Heyns, T. A conceptual framework for educational design at modular level to promote transfer of learning. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2015, 52, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botma, Y.; MacKenzie, M.J. Perspectives on transfer of learning by nursing students in primary healthcare facilities. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2016, 6, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compton, P.; Blacher, S. Nursing education in the midst of the opioid crisis. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2020, 21, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.J. A Comparison Between Unit-Based Education and Centralized Education Among Staff Nurses; Teachers College, Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Germossa, G.N.; Hellesø, R.; Sjetne, I.S. Hospitalized patients’ pain experience before and after the introduction of a nurse-based pain management programme: A separate sample pre and post study. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emergency Nurses Association. Sheehy’s Manual of Emergency Care-E-Book; Elsevier Health Sciences: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Welch-Coltrane, J.L.; Wachnik, A.A.; Adams, M.C.; Avants, C.R.; Blumstein, H.A.; Brooks, A.K.; Farland, A.M.; Johnson, J.B.; Pariyadath, M.; Summers, E.C.; et al. Implementation of individualized pain care plans decreases length of stay and hospital admission rates for high utilizing adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauw, D.J.; Essex, M.N.; Pitman, V.; Jones, K.D. Reframing chronic pain as a disease, not a symptom: Rationale and implications for pain management. Postgrad. Med. 2019, 131, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, A.P.; Adriana, P.N.; Laura, G.G.; Edith, M.C.; Emma, V.A. Reality, Delays, and Challenges within Pain Prevalence and Treatment in Palliative Care Patients: A Survey of First-Time Patients at the National Cancer Institute in Mexico. J. Palliat. Care 2021, 36, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkamani, A.M.; Atherton, R.; Dunbar, M.; McLeod, H.J. Development and testing of a checklist to assess compliance with the faculty of pain medicine’s core standards for pain management services: Experience in a new national tertiary pain service. Br. J. Pain 2020, 14, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.S.; Bashir, U. Teamwork in chronic pain management and the way forward in low and middle-income countries. Anaesth. Pain Intensive Care 2021, 25, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo-Van Dyk, L.; Botma, Y.; Ndhlovu, M.; Nyoni, C.N. A concept analysis on the transfer climate in health sciences education. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolobe, L.E. An Action Plan to Enhance the Transfer of Learning of Pain Management Competencies of Nurses in Saudi Arabian Teaching Hospitals. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2024; pp. 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Worth, M.J. Nonprofit Management: Principles and Practice; CQ Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research; SAGE publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bolarinwa, O.A. Sample size estimation for health and social science researchers: The principles and considerations for different study designs. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 27, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zizile, T.; Tendai, C. The importance of entrepreneurial competencies on the performance of women entrepreneurs in South Africa. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2018, 34, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizazu, M.A.; Asefa, E.Y.; Muluneh, M.A.; Haile, A.B. Utilizing a minimum of four antenatal care visits and associated factors in Debre Berhan town, North Shewa, Amhara, Ethiopia 2020. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2020, 13, 2783–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGurk SRMueser, K.T. Cognitive Remediation for Successful Employment and Psychiatric Recovery: The Thinking Skills for Work Program; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Niederberger, M.; Renn, O. Delphi Methods in the Social and Health Sciences; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2023; Volume 10, p. 978-3. [Google Scholar]

- Demissie, F.; Ereso, K.; Paulos, G. Self-medication practice with antibiotics and its associated factors among community of Bule-Hora Town, South West Ethiopia. Drug, Health Patient Saf. 2022, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice; Lippincott Williams Wilkins: Ambler, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, R.K.; Thomas, R.K. Strategic planning. In Health Services Planning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baljoon, R.A.; Banjar, H.E.; Banakhar, M.A. Nurses’ work motivation and the factors affecting It: A scoping review. Int. J. Nurs. Clin. Pract. 2018, 5, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, S.; Elwell, J.; Rigolosi, R.; Proto, M. Barriers and motivating factors for licensed practical nurses to pursue a bachelor’s degree in nursing. J. Prof. Nurs. 2024, 51, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahsay, D.T.; Pitkäjärvi, M. Emergency nurses knowledge, attitude and perceived barriers regarding pain Management in Resource-Limited Settings: Cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaie, N.; Vasli, P.; Sedighi, L.; Sadeghi, B. Comparing the effect of lecture and Jigsaw teaching strategies on the nursing students’ self-regulated learning and academic motivation: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 79, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.L. Introducing mesocredentials: Connecting MOOC achievement with academic credit. Distance Educ. 2022, 43, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, M.; Zvacek, S.M.; Smaldino, S. Teaching and Learning at a Distance: Foundations of Distance Education, 7th ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M. Strategizing information systems: An empirical analysis of IT alignment and success in SMEs. Computers 2019, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, J.; Hamilton, P.M. Pain Management for Oregon Nurses and Other Healthcare Professionals; Medical Education Inc.: Irwin, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore, S.J.; Rincon, M.A.; Buzaglo, J.S.; Golant, M.; Lieberman, M.A.; Bauerle Bass, S.; Chambers, S. Digital literacy linked to engagement and psychological benefits among breast cancer survivors in Internet-based peer support groups. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2019, 28, e13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, E.; Saha, S.; Allum, L.; Rose, L. An environmental scan of online resources for informal family caregivers of ICU survivors. J. Crit. Care 2024, 80, 154499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer-Macaulay, C.B.; Graham, R.J.; Williams, D.; Dorste, A.; Teele, S.A. “New Trach Mom Here…”: A qualitative study of internet-based resources by caregivers of children with tracheostomy. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadsell, R.; Rao, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Pascanu, R. Embracing change: Continual learning in deep neural networks. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovasi, O.; Lám, J.; Frank, K.; Schutzmann, R.; Gaál, P. The first comprehensive survey of the practice of postoperative pain management in Hungarian hospitals: A descriptive study. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2023, 24, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengyel, P.S. Learning in Online Environment: Let’s Focus on Emotional Awareness. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2023, 18, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleta, A.; Teshome, Z.; Zewdie, M. EFL Teachers’ Awareness and Accommodations of Learners’ Different Learning Styles in ELT Context: Two Colleges of Teachers’ Education in Oromia, Ethiopia. J. Sci. Technol. Arts Res. 2022, 11, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deocampo, M.F. Issues and challenges of English language teacher-trainees’ teaching practicum performance: Looking back and going forward. LEARN J. Lang. Educ. Acquis. Res. Netw. 2020, 13, 486–503. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Feng, G.; Wang, C.; Yang, D.; Hu, L.; Ming, W.K.; Chen, W. Nurses’ job preferences on the internet plus nursing service program: A discrete choice experiment. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, R.M.; Johnson, C.E.; Worsham, J.W. Development of an e-learning module to facilitate student learning and outcomes. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, L.; Østergaard, D. A qualitative study of the value of simulation-based training for nursing students in primary care. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiviniitty, N.; Kamau, S.; Mikkonen, K.; Hammaren, M.; Koskenranta, M.; Kuivila, H.M.; Kanste, O. Nurse leaders’ perceptions of competence-based management of culturally and linguistically diverse nurses: A descriptive qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6479–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Majumdar, R.; Chen, M.R.A.; Ogata, H. Goal-oriented active learning (GOAL) system to promote reading engagement, self-directed learning behavior, and motivation in extensive reading. Comput. Educ. 2021, 171, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, F.; Kibwana, S.; Shawula, S.; Misganaw, E.; Abosse, Z.; Van Roosmalen, J.; Mariam, D.W. Understanding job satisfaction and motivation among nurses in public health facilities of Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2019, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Wards | Medical | Surgical | Paediatric | Cardiac | Obs-Gynae | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B |

| Population RNs | 459 | 135 | 282 | 35 | 20 | 216 | 166 | 0 | 114 | 35 | 1041 | 421 |

| Sample size RNs | 210 | 101 | 163 | 33 | 20 | 139 | 117 | 0 | 89 | 33 | 281 | 202 |

| Population of CFs | 14 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 32 | 15 |

| Sample size of CFs | 14 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 30 | 15 |

| Round 1 (N = 12; f = 100%) Consensus reached Yes/No = (≥75%) | Round 2 (N = 12; f = 100%) Consensus reached Yes/No = (≥75%) | Round 3 (N = 10; f = 100%) Consensus reached Yes/No = (≥75%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.1 Action Statement:Motivate nurses to pursue further studies | 100% consensus reached that nurses must be motivated to further their studies (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 1.2 Methods | 100% consensus that a policy must be developed to motivate nurses to improve their nursing qualifications. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| Items to be included in the policy to motivate nurses were: 100% of respondents agreed that a certificate should be issued as an acknowledgement 83.3% agreed that one day off to attend a one-day pain management program 75% indicated that a monetary incentive after completion of the pain management program | Yes | Yes | ||

| 91.7% (n = 11) consensus reached that the policy should be presented and negotiated for the implementation to motivate nurses in their nursing qualifications (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 100% consensus was reached to include the policy as part of the hospitals’ polices after approval. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1.3 Responsible persons | 83.3% (n = 10; N = 12) agreed that the clinical director of nursing operations and the director of nursing education should be persons to develop the policy to motivate nurses to improve their qualifications. (No) | Only 41.7% (n = 5) of panelists indicated that a nursing policy committee representative should be responsible. (No) | 100% (N = 10) of panelists agreed that the nursing policy committee representative should be responsible for developing the policy that motivates nurses to further their nursing qualifications | |

| 75% (n = 9; N = 12) agreed that the nursing policy committee representatives. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 83.3% (n = 10) agreed that clinical directors of nursing operations and nurse managers in all nursing care areas to be responsible for including the policy in all hospitals’ policies. (No) | 66.7% panelists indicated nurse managers in all nursing care areas to include the policy in all hospitals’ polices to motivate nurses to improve their nursing qualifications (No) | 90% of panel members agreed that Clinical directors of nursing operations in every facility are responsible for including the policy in all hospitals’ policies | ||

| 1.4 Time frame | 75% (n = 9; N = 12) agreed that 4–6 months was needed for policy development. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| No consensus reached by panelists on the time frame to present the policy and for its implementation (No) | 66.7% of the panelists indicated the time frame to present the policy and for its implementation within 6 months (No) | 90% consensus was reached that 6 months is a required time frame to present the policy and negotiate for the implementation (Yes) | ||

| No consensus reached as panelists had diverse opinions on the time frame to include the policy in all hospitals’ policies after approval by the hospitals (No) | 75% (n = 9) of panelists reached consensus to include the policy within 3 months after approval of the action plan (Yes) | Yes | ||

| Quotes | “When there’s a policy, the organization will encourage nurses by giving them a day off or an education day.” “A policy must specify that an employee should have worked for the organization for at least two years.” P1 “A policy must specify that an employee should have worked for the organization for at least two years before he or she can apply for this course.” P2 | None | None | |

| 2 | 2.1 Action statement: Provide the nursing team with appropriate pain management tools | 91.7% consensus reached that an appropriate and relevant pain management tool must be made available (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 2.2 Methods | No consensus was reached as the panelists had diverse views on including pain assessment tools in an electronic patient record system (No) | Yes | 90% (n = 9) of panelists agreed that the pain assessment tools should be included in the electronic patient record system (Yes) | |

| Tools to be accessible on the electronic were: 66.7% selected the PQRST guide assessment tool 66.7% panelists chose the CRIES pain scale (No) | ||||

| 83.3% consensus was reached to involve nurse supervisors with pain management training and supervisory support. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 91.7% of paternalists reached consensus that internet-based resources should be accessible to the patients and family members (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 91.7% consensus was reached that the hospital’s intern-based resources on pain management publications should be accessible to nursing staff (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Internet-based resources that should be included were: 83.3% of panelists agreed that patient pain management websites and support groups should be accessible (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 100% consensus was reached that hospitals’ internet-based resources on pain management publications and electronic materials should be accessible to nursing staff (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Internet-based resources to be accessible were: 83.3% selected pain toolkits 75% agreed to be videos on pain management and clinical updates (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2.3 Responsible persons | 91.7% panelists indicated that the associate director of informatics to include pain assessment tools in the electronic patient record system 75% agreed on one pain nurse specialist to include pain assessment tools in the electronic patient record system (No) | 75% panelists agreed that one pain nurse specialist should be appointed in every facility to ensure that the electronic format on pain assessment tools is included in the electronic patient record system (Yes) | Yes | |

| 75% indicated the clinical directors of nursing operations and clinical facilitators in all nursing care areas as responsible persons to involve nurse supervisors with pain management training to provide supervisory support to the nursing staff (No) | 50% (n = 6) of the panelists selected the persons to be clinical directors of nursing operations and clinical facilitators in all nursing care areas, to involve nurse supervisors to provide supervisory support to nursing staff. (No) | 90% indicated that clinical directors of operations to involve nurse supervisors to provide supervisory support to nursing staff (Yes) | ||

| No consensus reached as the panelists indicated diverse views about persons to ensure internet-based resources on pain management should be accessible to the nursing staff in all nursing care areas (No) | 58.3% indicated one pain nurse specialist in every facility to ensure internet-based resources on pain management (No) | 90% agreed that clinical directors of nursing operations are responsible for ensuring internet-based resources on pain management publications are accessible to nursing staff in all areas (Yes) | ||

| 2.4 Time frame | 58.3% indicated a 4–6-month timeframe to include the pain assessment tools in the electronic patient record system (No) | 58.3% of panelists indicated the time frame of 1 to 3 months within which pain assessment tools should be available in the electronic patient record system. (No) | 90% consensus was reached that 1 to 3 months should be the time frame within which pain assessment tools should be available (Yes) | |

| 66.7% selected that every patient round should be done when needed as a time frame, to involve a nurse supervisor (No) | No consensus reached on time frame as panelists gave diverse opinions | 100% agreed that every shift, when need arises, as a time frame that nurse supervisors should be involved in providing pain management training and supervisory support. (Yes) | ||

| 75% panelists agreed that 24 h access 7 days a week, a time frame to make the hospital’s internet-based resources accessible to support patients and family about pain management. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 75% panelists agreed that the hospital’s internet-based resources should be continuously available to the nursing team (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Quotes | None | None | ||

| 3 | 3.1 Action statement:Develop a practice-oriented, content-specific short training program for pain management | 100% of panelists agreed that a practice-oriented, content-specific short pain management training must be developed. (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 3.2 Methods | 100% agreed to include specific practice-oriented pain management training content for all nursing care areas (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| Specific methods were: 91.7% agreed that the assessment of patients as important content 83.3% panelists agreed that the selection of appropriate pain strategies based on pain levels should be assessed. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 3.3 Responsible persons | 91.7% (n = 11) agreed that on pain nurse specialist should be in every facility (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| 3.3 Time frame | Only 66.7% agreed on 1 month before the due date of the training program (No) | 83.3% consensus was reached that specific practice-oriented pain management content should be included in the program. (Yes) | Yes | |

| Quotes | None | None | Yes | |

| 4 | 4.1 Action statement: Develop a short pain management program that accommodates all learning types. | 100% (N = 12) of the panelists were in agreement. (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 4.2 Methods | 100% (N = 12) consensus was reached that different learners should be incorporated during training sessions (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| Specific different learner types of nurses were: 100%(n = 12) agreed on creative learners 91.7% agreed to include creative learners 75% (n = 9) agreement on organized thinkers | Yes | Yes | ||

| Specific different learning types to incorporate during pain management training were: 100% (N = 12) agreed to be creative ideas in groups 66.7% (n = 8) of panelists agreed that it should be listening to the information actively, solving different real problems | ||||

| 4.3 Responsible persons | 75% (n = 9) of the panelists agreed that one pain nurse specialist should be responsible (Yes) | Yes | ||

| 4.4 Time frame | No consensus. All panelists had diverse views | 83.3% agreed that 3 months before the due date of the training program, to ensure learning types are incorporated within the training program (Yes) | Yes | |

| Quotes | None | None | None | |

| 5 | 5.1 Incorporate different teaching approaches to accommodate diverse learners and facilitators in the training of pain management. | 100% (N = 12) panelists agreed that various teaching approaches should be included during the training program. (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 5.2 Methods | 100% (N = 12) of panelists agreed on the inclusion of different teaching strategies during training (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| Specific teaching strategies to be utilised include: 75% selected engagement in focus groups 66.7% agreed on the use of role-play activities (Yes) | Yes | Yes | ||

| 5.3 Responsible persons | 75% (N-12) consensus selected one pain nurse specialist in every facility. (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| 5.4 Time frame | No consensus reached, panelists had diverse opinions (No) | 75% consensus reached that different teaching strategies to be included to be part of the training program | ||

| Quotes | None | None | None | |

| 6 | 6.1 Action statement: Develop strategies to motivate nurses to participate in the short training program | 100% of panelists agreed that strategies to motivate nurses to participate in the short training program should be developed. (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 6.2 Methods | 83.3% consensus to involve nurses in the development of learning goals and outcomes for pain management 75% agreed on the involvement of nurses in developing the content of the training (Yes) | (Yes) | Yes | |

| 6.3 Responsible persons | 83.3% (n = 10) agreed that one pain nurse specialist should be appointed. 75% (n = 9) believed the in all areas of nursing care areas (No) | 75% agreed that one pain nurse specialist in every facility to develop the mentioned strategies, motivating nurses’ participation (Yes) | Yes | |

| 6.4 Time frame | 75% (n = 9) panelists agreed that 1 month before the training program starts was appropriate (Yes) | No consensus on time frame was reached as all panelists had different views | ||

| Quotes | None | None | None | |

| 7 | 7.1 Action Statement: Motivate nurses to apply the knowledge gained in the training program into practice | 100% (N = 12) consensus was reached that nurses must be motivated to apply their knowledge gained in the training program into practice (Yes) | Yes | Yes |

| 7.2 Methods | Several methods were agreed upon to motivate nurses: 100% (N = 12) of nurses should be offered the opportunity to take on the role of pain management. 75% (n = 9) agreed on supporting nurses’ SMART goals and pain management learning 75% (n = 9) agreed that aspects that drive individual nurses to apply what they have learned should be supported (Yes) | Yes | Yes | |

| 7.3 Responsible persons | 91.7% (n = 11) panelists chose nurse managers in all nursing care areas, 75% (n = 9) of the panelists agreed that clinical directors of nursing operations to be responsible (No) | 75% agreed that clinical directors of nursing operations should facilitate the implementation of the methods to motivate nurses to apply their knowledge in practice. (Yes) | Yes | |

| 7.4 Time frame | No consensus reached as most panelists had diverse views. (No) | Panelists did not reach an agreement (No) | 90% consensus was reached on 1 to 3 months after the training program as a time frame | |

| Quotes | None | None | None |

| Characteristics | Registered Nurses (RNs) | Clinical Facilitators (CFs) | Cumulative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=) | %= | (n=) | % | (N=) | %= | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 10 | 83.3 | 2 | 16.7 | 12 | 100 |

| Males | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Education | ||||||

| Master’s degree | 2 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 18.7 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 | 58.3 | 2 | 16.7 | 9 | 75 |

| Diploma in Nursing | 3 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 100 |

| Nationality | ||||||

| Filipino | 5 | 41.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 6 | 50 |

| South African | 2 | 16.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 9 | 75 |

| Malaysian | 2 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 11 | 91.6 |

| Saudi | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 100 |

| Action statements | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Action Statements | Motivate Nurses to Further Their Studies. | Provide the Nursing Team with Appropriate Pain Management Tools | Develop a Practice-Oriented, Content-Specific Pain Management Short Training | Develop a Short Pain Management Program That Accommodates All Learning Types. | Incorporate Different Teaching Approaches to Accommodate Diverse Learners and Facilitators in the Training of Pain Management. | Develop Strategies to Motivate Nurses to Participate in the Short Training Program. | Motivate Nurses to Apply the Knowledge Gained in the Training Program into Practice. |

| Methods suggested to achieve the action goal and expected outcomes | Develop a policy to motivate nurses. | Integrate all pain assessment instruments in an electronic patient record system. | Provide pain management training content that focuses on practical application. | Develop a training program that is flexible enough to accommodate a variety of learning types and learning styles used by nurse trainees. | Ensure the training program includes a variety of teaching methods, such as focus groups and role-play. | Include practice-oriented pain management content | Accommodate different learning types and learning styles. |

| Propose and advocate for the adoption of the policy to (MNGHA) | Engage nurse supervisors in pain management training. | ||||||

| Incorporate the policy into the policies of all hospitals | Ensure that all internet-based resources of hospitals are easily accessible | ||||||

| Provide the nursing team with access to all hospitals’ internet-based resources | |||||||

| Responsible person to implement | Representatives of the nursing policy committee Directors of nursing operations | Clinical Directors | Pain nurse specialist | Pain nurse specialist | Pain nurse specialist | Pain nurse specialist | Nurse managers |

| Time frame | Four to six months after the MNGHA approves the action plan | To be incorporated into the electronic patient record system within 2–3 months | Three months before the training program’s deadline | Three months before the training program’s deadline | Three months before the date on which the training program is to be executed | One month before the training program’s launch | Within one to three months following the training program |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolobe, L.E.; Roets, L. An Action Plan to Facilitate the Transfer of Pain Management Competencies Among Nurses. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120442

Kolobe LE, Roets L. An Action Plan to Facilitate the Transfer of Pain Management Competencies Among Nurses. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120442

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolobe, Litaba Efraim, and Lizeth Roets. 2025. "An Action Plan to Facilitate the Transfer of Pain Management Competencies Among Nurses" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120442

APA StyleKolobe, L. E., & Roets, L. (2025). An Action Plan to Facilitate the Transfer of Pain Management Competencies Among Nurses. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120442