Moving4notfrail®: A Rehabilitation Nursing Programme for Older Adults with Frailty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

2.3.1. First Round

2.3.2. Second Round

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

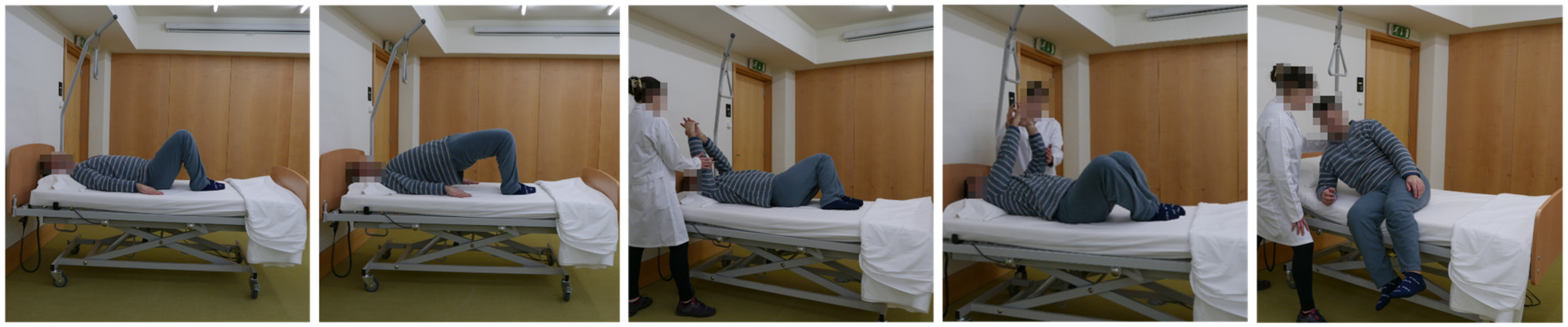

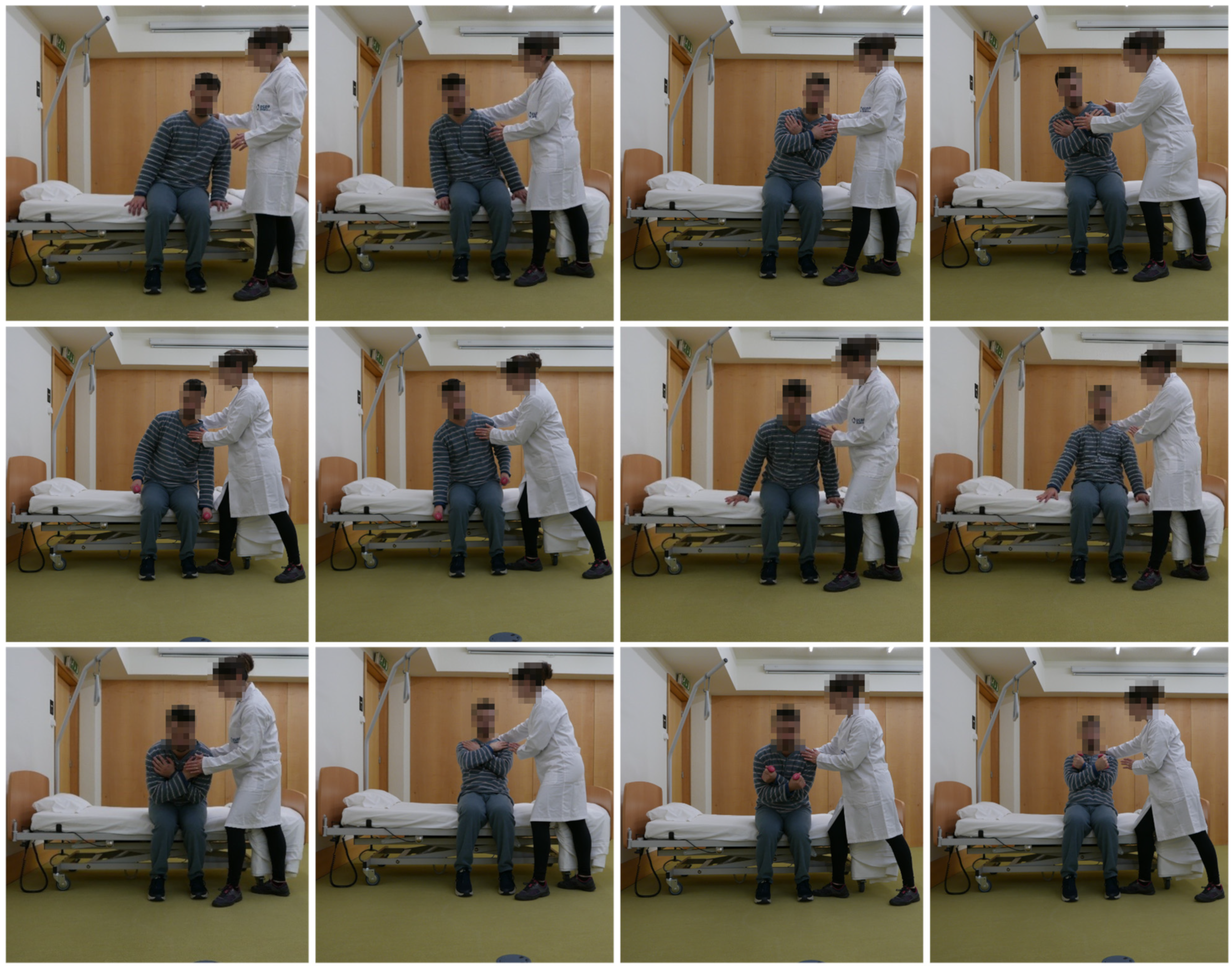

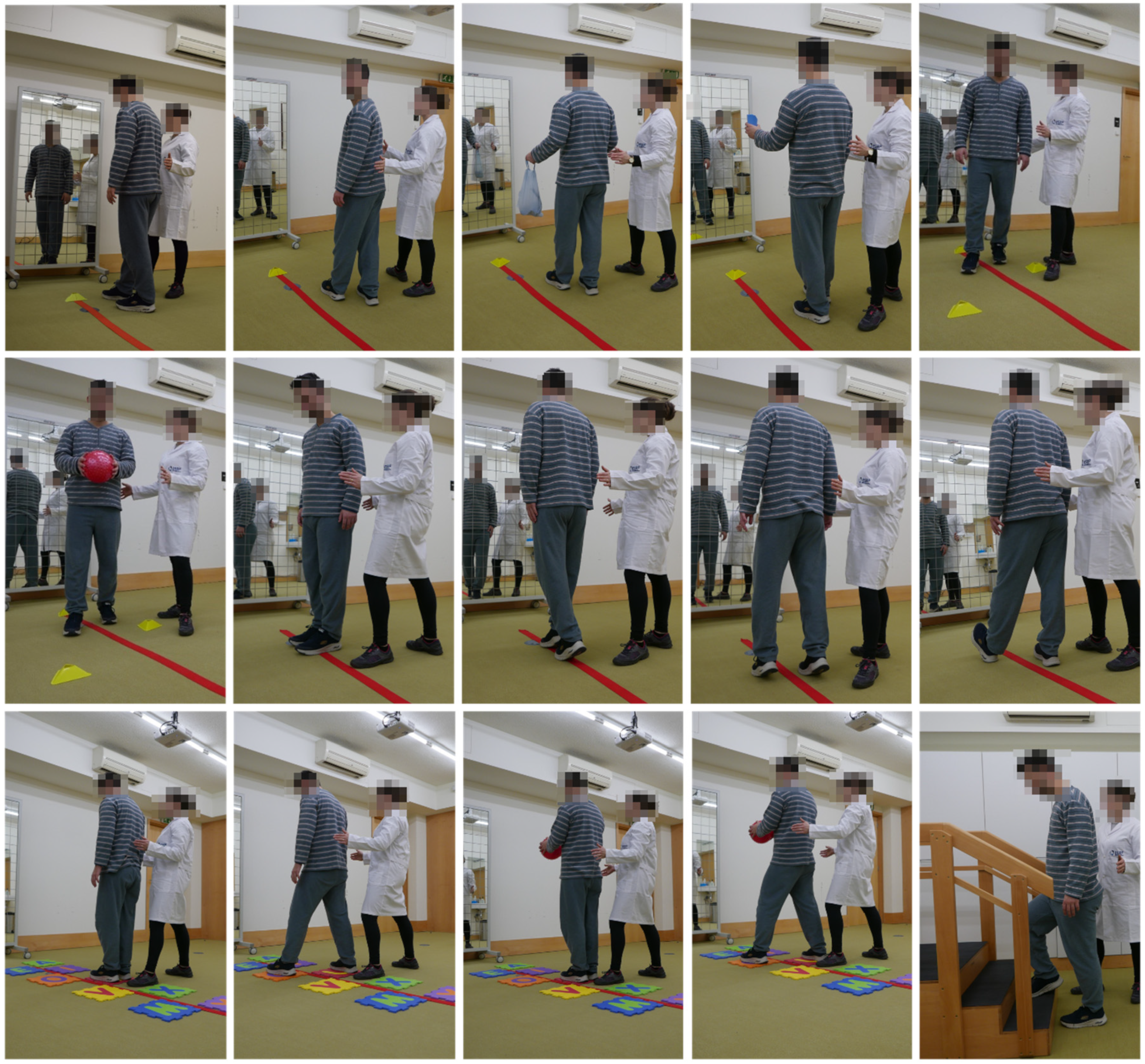

3.1. Phase I—Development of the Rehabilitation Nursing Programme for Older Adults with Physical Frailty Admitted to Hospital

3.2. Phase II—Content Validation of the “Moving for Not Frail: Rehabilitation Nursing Programme”

3.3. Development of the Final Prototype of the “Moving for Not Frail: Rehabilitation Nursing Programme”

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Practice

4.2. Limitations and Future Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SNRN | Specialist Nurses in Rehabilitation Nursing |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CVI | Content Validity Index |

References

- PORDATA. Retrato de Portugal. Available online: https://www.pordata.pt/europa/anos+de+vida+saudavel+a+nascenca+total+e+por+sexo-3654 (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Lopes, D.G.; Mendonça, N.; Henriques, A.R.; Branco, J.; Canhão, H.; Rodrigues, A.M. Trajectories and Determinants of Ageing in Portugal: Insights from EpiDoC, a Nationwide Population-Based Cohort. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing 2022: Report of Consortium Meeting, 5–6 December 2022; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, O.M.; Pinto, C.; Regadas, S.C. People Dependent in Self-Care: Implications for Nursing. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2014, 4, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, N. A Research Framework for the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing (2021–2030). Eur. J. Ageing 2022, 19, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobbens, R.J.; Vermeiren, S.; Van Hoof, A.; van der Ploeg, T. Nurses’ Opinions on Frailty. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, M.; Damanti, S.; Germini, F.; Apostolo, J.; Bobrowicz-Campos, E.; Gwyther, H.; Holland, C.; Kurpas, D.; Bujnowska-Fedak, M.; Szwamel, K.; et al. Interventions to prevent, delay or reverse frailty in older people: A journey towards clinical guidelines. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Morley, J.E.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Woodhouse, L.; Rodríguez-Mañas, L.; Fried, L.P.; Woo, J.; Aprahamian, I.; Sanford, A.; Lundy, J.; et al. Physical Frailty: ICFSR International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Identification and Management. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Clinical Consortium on Healthy Ageing. Topic Focus: Frailty and Intrinsic Capacity. Report of Consortium Meeting, 1–2 December 2016 in Geneva, Switzerland; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-FWC-ALC-17.2 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Antoniadou, E.; Giusti, E.; Capodaglio, P.; Han, D.S.; Gimigliano, F.; Guzman, J.M.; Oh-Park, M.; Frontera, W.; Expert Panel. Frailty recommendations and guidelines: An evaluation of the implementability and a critical appraisal of clinical applicability by the ISPRM Frailty Focus Group. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 60, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, M.W.; Mallery, K.; Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. Impact of Hospitalization on Patients’ Ability to Perform Basic Activities of Daily Living. Can. Geriatr. J. 2023, 26, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Mendes, M.E.; Santos, L.; Preto, L.; Azevedo, A. Declínio Funcional em Idosos Durante a Hospitalização. Rev. Port. Enferm. Reabil. 2023, 6, e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation No. 392/2019, 3 May; Diário da República; Série II; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

- Gil, A.; Sousa, F.; and Martins, M.M. Implementation of a Rehabilitation Nursing Program in Elderly People with Fragility/Disuse Syndrome-Case Study. Rev. Port. Enferm. Reabilitação 2020, 3, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 10th ed.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Faria, A.d.C.A.; Martins, M.M.F.P.S.; Ribeiro, O.M.P.L.; Ventura-Silva, J.M.A.; Fonseca, E.F.; Ferreira, L.J.M.; Teles, P.J.F.C.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A. Multidimensional Frailty and Lifestyles of Community-Dwelling Older Portuguese Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, A.d.C.A.; Martins, M.M.; Laredo-Aguilera, J.A.; Ventura-Silva, J.M.A.; Ribeiro, O.M.P.L. Development and Validation of a Game for Older Adults on Lifestyles and Frailty. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 2499–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation No. 140/2019, 2 February; Diário da República, No. 26; Série II; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2019.

- Regulation No. 350/2015, 22 June; Diário da República, No. 119; Série II; Ministério da Saúde: Lisbon, Portugal, 2015.

- Jünger, S.; Payne, S.A.; Brine, J.; Radbruch, L.; Brearley, S.G. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagesch, M.; Chocano-Bedoya, P.O.; Abderhalden, L.A.; Freystaetter, G.; Sadlon, A.; Kanis, J.A.; Kressig, R.W.; Guyonnet, S.; DaSilva, J.A.P.; Felsenberg, D.; et al. Prevalence of Physical Frailty: Results from the DO-HEALTH Study. J. Frailty Aging 2021, 11, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfredi, G.; Midão, L.; Paúl, C.; Cena, C.; Duarte, M.; Costa, E. Prevalence of Frailty Status among the European Elderly Population: Findings from the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitter, J.G.; Zemplényi, A.; Babarczy, B.; Németh, B.; Kaló, Z.; Vokó, Z. Frailty prevalence in 42 European countries by age and gender: Development of the SHARE Frailty Atlas for Europe. Geroscience 2024, 46, 1807–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, T.; Kinsman, L.; James, E.; Machotta, A.; Gothe, H.; Willis, J.; Snow, P.; Kugler, J. Clinical Pathways: Effects on Professional Practice, Patient Outcomes, Length of Stay and Hospital Costs. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 7, CD006632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, R.B.; Hommel, K.; van Dulmen, S. Effects of Clinical Pathways in Hospital-Based Care: A Systematic Review. J. Public Health 2024, 32, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, K.; Crotty, M.; Kurrle, S.E.; Cameron, I.D.; Lane, R.; Lockwood, K.; Block, H.; Sherrington, C.; Pond, D.; Nguyen, T.A.; et al. Hospital-Based Health Professionals’ Perceptions of Frailty in Older People. Gerontologist 2024, 64, gnae041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prommaban, A.; Moonkayaow, S.; Phinyo, P.; Siviroj, P.; Sirikul, W.; Lerttrakarnnon, P. The Effect of Exercise Program Interventions on Frailty, Clinical Outcomes, and Biomarkers in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International exercise recommendations in older adults (ICFSR): Expert consensus guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caicedo-Pareja, M.; Espinosa, D.; Jaramillo-Losada, J.; Ordoñez-Mora, L.T. Physical Exercise Intervention Characteristics and Outcomes in Frail and Pre-Frail Older Adults. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, J.; Ren, J.; Wang, J.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, S.; Wu, S.; Xie, L. Combining motivational and exercise intervention components to reverse pre-frailty and promote self-efficacy among community-dwelling pre-frail older adults: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porto, M.; Lorenzi, L.J.; Marson, M.A.G.; Belo, L.F.; da Silva Sobrinho, A.C.; Bet, P.; Delinocente, M.L.B.; de Oliveira Gomes, G.A. Characteristics of frailty prevention interventions addressed to robust and pre-frail older adults: A scope review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2025, 65, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Cadore, E.L. Multicomponent Exercise with Power Training: A Vital Intervention for Frail Older Adults. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2024, 28, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Song, X.; Bao, J.; Liao, S.; Xi, Y.; Guo, G. Effects of multicomponent exercise on frailty status and physical function in frail older adults: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 197, 112604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y.; Samsudin, S.A.; Lim, Y.J. Older patients’ perception of engagement in functional self-care during hospitalization. Geriatr. Nurs. 2020, 41, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zepeda, M.U.; Martínez-Velilla, N.; Kehler, D.S.; Izquierdo, M.; Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. The impact of an exercise intervention on frailty levels in hospitalised older adults. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falvey, J.R.; Ye, J.Z.; Parker, E.A.; Beamer, B.A.; Addison, O. Rehabilitation outcomes among frail older adults in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Herrero, A.; Anton-Rodrigo, I.; Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Sáez de Asteasu, M.L.; Martinez-Velilla, N.; Elexpuru-Estomba, J.; Marin-Epelde, I.; Ramon-Espinoza, F.; Petidier-Torregrosa, R.; Sanchez-Sanchez, J.L.; et al. Effect of a multicomponent exercise programme (VIVIFRAIL) on functional capacity in frail community elders with cognitive decline: Study protocol for a randomized multicentre controlled trial. Trials 2019, 20, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription, 11th ed.; Liguori, G., Feito, Y., Fountaine, C., Roy, B.A., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Health: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fragala, M.S.; Cadore, E.L.; Dorgo, S.; Izquierdo, M.; Kraemer, W.J.; Peterson, M.D.; Ryan, E.D. Resistance training for older adults: Position statement from the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33, 2019–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.; Menegyi, Ç. Effects of exercise-cognitive dual-task training on elderly patients with cognitive frailty and depression. World J. Psychiatry 2022, 15, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhong, L. Assessing the impact of frailty interventions on older patients with frailty. Curr. Ther. Res. 2024, 102, 100769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradell, A.; Iguacel, I.; Navarrete-Villanueva, D.; Fernández-García, Á.I.; González-Gross, M.; Pérez-Gómez, J.; Ara, I.; Casajús, J.A.; Gómez-Cabello, A.; Vicente-Rodríguez, G. Effects of a multicomponent training and a detraining period on cognitive and functional performance of older adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2025, 37, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; de Souto Barreto, P.; Arai, H.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; Chen, L.-K.; Coen, P.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Duque, G.; et al. Global consensus on optimal exercise recommendations for enhancing healthy longevity in older adults (ICFSR). J. Nutr. Health Aging 2025, 29, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.; Yao, J.; Lu, Y. The effects of Vivifrail-based multicomponent training on physical and cognitive function in frail older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1646833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlima, S.D.; Hall, A.; Aminu, A.Q.; Akpan, A.; Todd, C.; Vardy, E.R. Frailty: A global health challenge in need of local action. BMJ Glob. Health 2024, 9, e015173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.; Martins, M.M.; Tronchin, D. Nursing care quality: A study carried out in Portuguese hospitals. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2017, 4, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic and Professional Characteristics | First and Second Rounds (n = 18) |

|---|---|

| Gender n (%) | |

| Female | 11 (61.1%) |

| Male | 7 (38.9%) |

| Age (years) Mean; Std. Dev. | 38.7; ±7.7 |

| Education n (%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 7 (38.9%) |

| Master’s degree | 11 (61.1%) |

| Job Title n (%) | |

| Nurse | 5 (27.8%) |

| Nurse Specialist | 13 (72.2%) |

| Area of specialization in Nursing n (%) | |

| Rehabilitation nursing | 18 (100%) |

| Time of professional practice (years) Mean; Std. Dev. | 15.8; ±7.8 |

| Time of professional practice as a rehabilitation nursing specialist (years) Mean; Std. Dev. | 7.9; ±3.6 |

| Programme Components | CVI First Round | CVI Second Round |

|---|---|---|

| Programme steps | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Resources used in the programme | 0.89 | 1.00 |

| Session frequency | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Session duration | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Variety of exercises | 0.89 | 1.00 |

| Exercise progression | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, A.I.T.M.; Faria, A.d.C.A.; Gomes da Rocha, C.; Fernandes, A.; Gonçalves, M.F.M.; Quintas, J.I.A.; Gonçalves, M.N.d.C.; Ribeiro, O.M.P.L. Moving4notfrail®: A Rehabilitation Nursing Programme for Older Adults with Frailty. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120419

Santos AITM, Faria AdCA, Gomes da Rocha C, Fernandes A, Gonçalves MFM, Quintas JIA, Gonçalves MNdC, Ribeiro OMPL. Moving4notfrail®: A Rehabilitation Nursing Programme for Older Adults with Frailty. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(12):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120419

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Ana Isilda Torres Martins, Ana da Conceição Alves Faria, Carla Gomes da Rocha, Abel Fernandes, Mariana Filipa Mendes Gonçalves, Joana Isabel Alves Quintas, Maria Narcisa da Costa Gonçalves, and Olga Maria Pimenta Lopes Ribeiro. 2025. "Moving4notfrail®: A Rehabilitation Nursing Programme for Older Adults with Frailty" Nursing Reports 15, no. 12: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120419

APA StyleSantos, A. I. T. M., Faria, A. d. C. A., Gomes da Rocha, C., Fernandes, A., Gonçalves, M. F. M., Quintas, J. I. A., Gonçalves, M. N. d. C., & Ribeiro, O. M. P. L. (2025). Moving4notfrail®: A Rehabilitation Nursing Programme for Older Adults with Frailty. Nursing Reports, 15(12), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15120419