Facilitators, Barriers, and Educational Preparedness of Early-Career Nursing Graduates Entering Practice in Rural and Remote Areas: A Mixed-Method Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

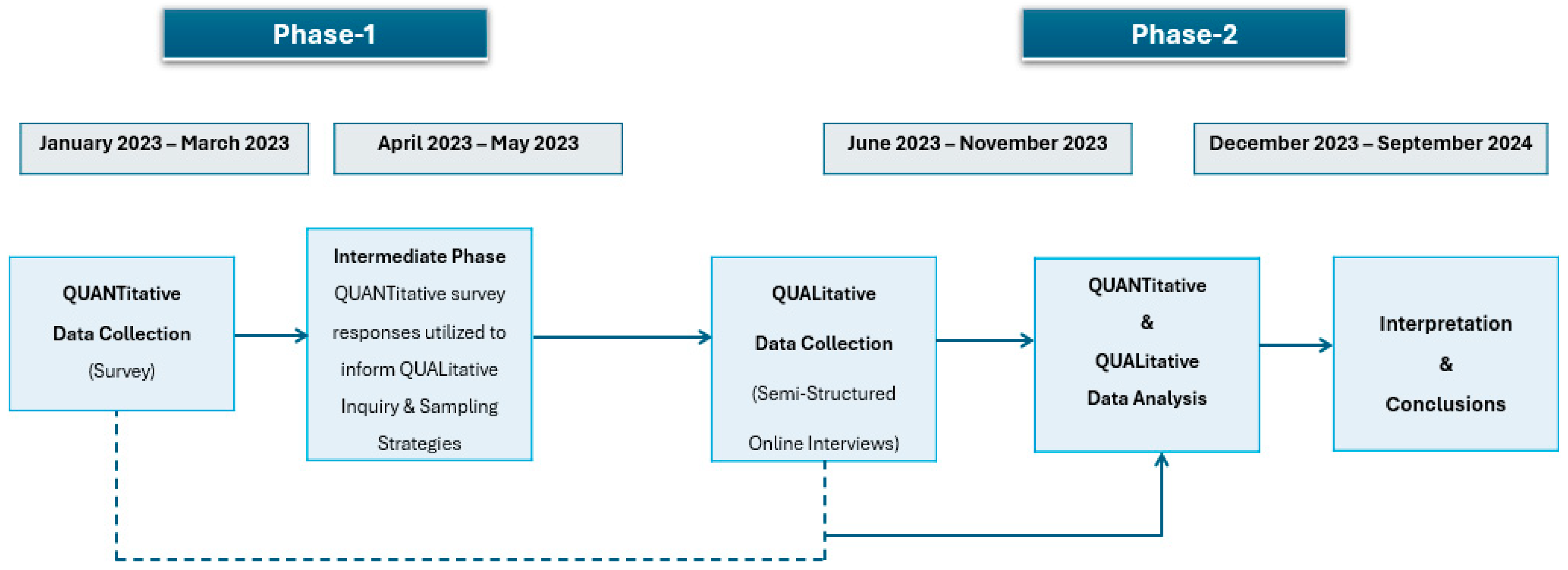

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Participant Recruitment

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Phase

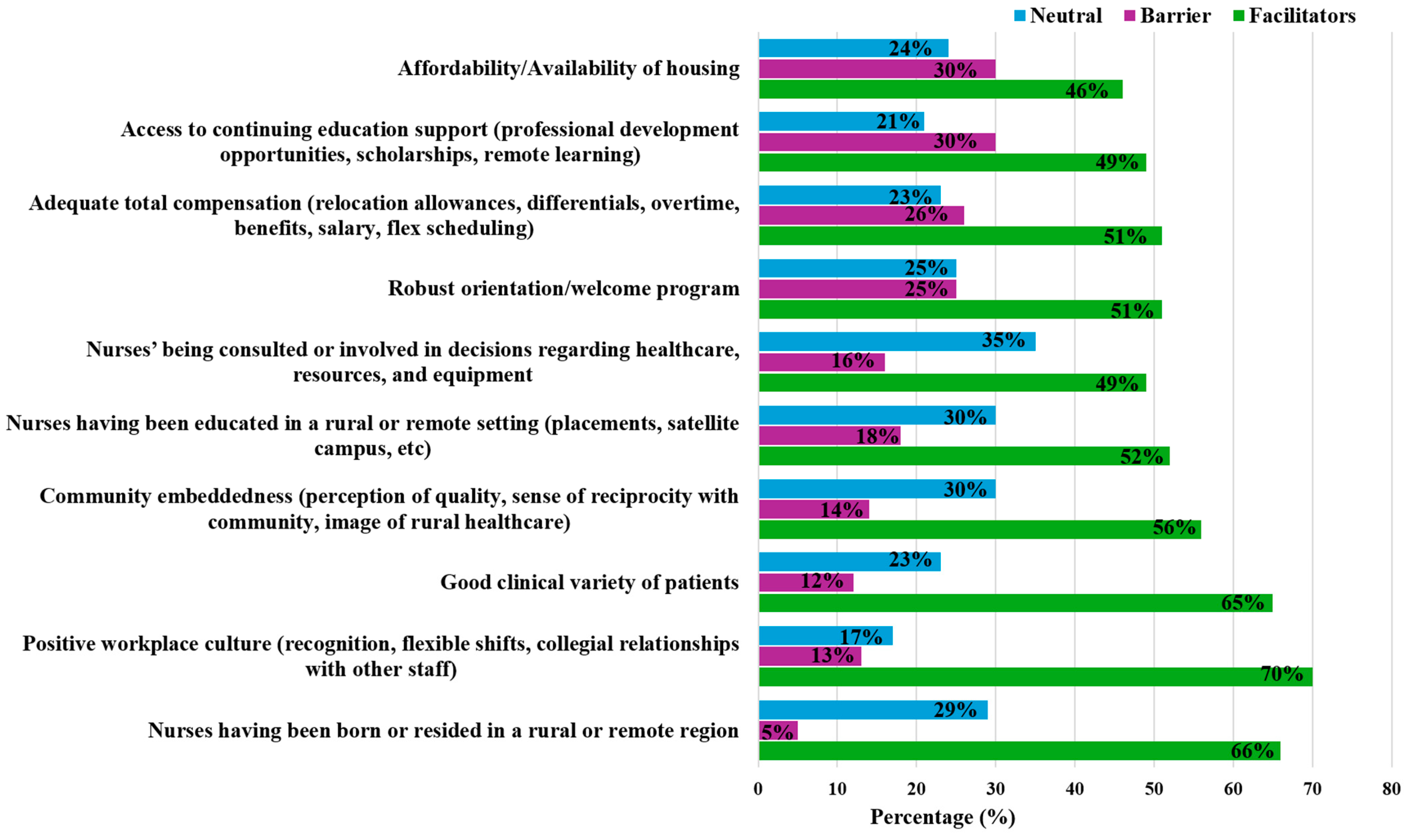

3.2. Facilitators and Barriers

3.3. Qualitative Phase

3.4. Qualitative Interpretive Descriptions and Themes

3.5. Barriers

3.5.1. Resources

“I realized I am really on my own up here and I need to get creative with how I do things … No doctor on site, limited labs, and diagnostics…”RN Northern Regional Health Authority

“It does not usually end in a great outcome for the patient. If we don’t have the resources to help them, they can’t get out. It can be very scary.”RN Prairie Mountain Regional Health Authority

3.5.2. Staffing

“Trying to get staff to come to the rural area is a big challenge not only for nurses but for the whole care team. Having all those staffing issues comes with having to work doubles and being mandated.”RN Prairie Mountain Regional Health Authority

“Our observation unit is closed in the E.R. because we don’t have the staff to keep the four beds open. So, I feel like it’s kind of domino effect and just overall not very good for the patients seeking care.”RN Southern Regional Health Authority

“I think it’s a great thing that these agency nurses come and help us out … But it’s like you’re orienting a new person every single day. They don’t understand the same policies …or they don’t know where stuff is … So sometimes you’re better doing things yourself and that can get frustrating.”RN Prairie Mountain Regional Health Authority

3.5.3. Geography

“Geography is always a challenge; we still get quite severe storms and that shuts the highways down … and you have to stabilize a patient for 48 h before the roads open back up so you can get them out.”RN Prairie Mountain Regional Health Authority

“When there’s weather and things that you can’t predict, patients don’t get to go to their appointments … which is the last step for them going home, it’s very frustrating.”RN Northern Regional Health Authority

3.5.4. Expanded Role

“If we’re going to see a patient in the ER after 4, for and emergency, the nurse would do the EKG, and we would draw lab work as well.”RN Southern Regional Health Authority

“It felt horrible being in charge … I was there for 8 months and there were no RNs on shift, and I was the most senior LPN so I was charge by default and it’s stressful to manage everything … I was not prepared.”LPN Interlake Eastern Regional Health Authority

3.6. Facilitators

3.6.1. Generalist Role

“I do like the opportunity to see a lot of different things … the medicine unit is combined palliative care … I think that’s cool that I can kind of practice two specialties and being able to see so many different … Systems, like cardiac GI, GU, on the same medicine unit.”RN Southern Regional Health Authority

“I like the diversity of patients … it’s ever changing. There’s always something new going on. I feel like I’m always learning every day. And I think it’s been fantastic … I wouldn’t necessarily be doing that if I was in Winnipeg unless I was in a float position.”RN Northern Regional Health Authority

3.6.2. Autonomy

“I do love the autonomy of rural nursing. I feel like I’m very close with the doctors. They trust our nursing judgment. We create plans together, and they respect our opinions.”RN Prairie Mountain Regional Health Authority

“The physicians are eager to kind of teach and you can ask any questions. I feel like the relationship is pretty good with the physicians.”LPN Southern Regional Health Authority

3.6.3. Rural Life

“Rural nursing is for me. I like it. Because it’s a small community, and I like it because it’s peaceful and quiet. It is less stressful than living in the city. Our cost of living is not that so expensive so I can work less.”RN Southern Regional Health Authority

3.6.4. Organizational Culture

“I would say that the overall kind of teamwork and camaraderie much better in the North.”RN Northern Regional Health Authority

“I worked 2 days in Winnipeg, and I am exhausted and drained. They appreciate us so much more Northern and I’m on day 5 of 7 and feeling like I still have so much energy.”RN Northern Regional Health Authority

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Rural Nursing Practice

4.2. Barriers to Rural Nursing Practice

4.3. Facilitators to Rural Nursing Practice

4.4. Transition into Nursing Practice

4.5. Educational Preparedness of Newly Graduated Nurse

4.6. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

4.7. Recommendations

- Undergraduate Nursing Curriculum:

- Increase capacity for rural placements in all clinical courses;

- Increase the threading of R&R content throughout theory courses;

- Consider the creation of a dedicated rural nursing elective to provide more exposure to R&R complexities in nursing;

- Facilitate R&R tours or rural clinical placements for nursing students who may wish to consider this career choice;

- Expand satellite nursing campuses so nurses can learn where they live and will eventually practice;

- Expand opportunities for final practicum placements in R&R settings;

- Increase partnerships with First Nations Communities and consider clinical opportunities in these settings.

- Practice:

- Extend monetary and housing incentives for remote nurses;

- Improve retention bonuses for nurses seeking employment in these settings;

- Expand the provincial nursing float pool system;

- Develop more robust orientation and preceptorship programs for new graduates;

- Consider self-scheduling and increase flexibility in work life for staff;

- Create a positive workplace culture that encourages new graduates to work in these settings;

- Expanding continuing education opportunities and subsidizing the cost of additional training in an urban setting.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

References

- Government of Canada SC. Population Growth in Canada’s Rural Areas, 2016 to 2021. 2022. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-x/2021002/98-200-x2021002-eng.cfm (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Registered Nurses. 2020. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/registered-nurses (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Canadian Nurses Association. Nursing Statistics. 2025. Available online: https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/nursing/regulated-nursing-in-canada/nursing-statistics (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. The State of the Health Workforce in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/en/the-state-of-the-health-workforce-in-canada-2022 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Pavloff, M.; Edge, D.S.; Kulig, J. A framework for nursing practice in rural and remote Canada. Rural Remote Health 2022, 22, 7545. [Google Scholar]

- AbdELhay, E.S.; Taha, S.M.; El-Sayed, M.M.; Helaly, S.H.; AbdELhay, I.S. Nurses retention: The impact of transformational leadership, career growth, work well-being, and work-life Balance. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, V.; Anderson, J.; West, S.; Cleary, M. Does the COVID-19 Pandemic Further Impact Nursing Shortages? Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 43, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Sapiro, N.; Martens, R.; Harmon, M.; Risling, T.; Eastwood, C. Trends and indicators of nursing workforce shortages in Canada: A retrospective ecological study, 2015–2022. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e092114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada SC. Profile Table, Census Profile, 2021 Census of Population—Manitoba [Province]; Winnipeg [Census Metropolitan Area], Manitoba. 2022. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Kulig, J.C. Health in Rural Canada, 1st ed.; Vancouver, B.C., Ed.; UBC Press: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2012; Available online: https://www.ubcpress.ca/asset/9079/1/9780774821728.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Manitoba Bureau of Statistics. Annual Population Statistics Regional Analysis. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.mb.ca/mbs/publications/mbs506_pop_region_2024_a01.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Canadian Association of Rural and Remote Nursing. Rural and Remote Nursing Practice in Canada: An Updated Discussion Document. 2020. Available online: https://carrn.com/images/pdf/CARRN_RR_discussion_doc_final_LR-2.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Canadian Association of Rural and Remote Nursing. Knowing the Rural Community: A Framework for Nursing Practice in Rural and Remote Canada. 2021. Available online: https://carrn.com/images/pdf/CARRN_RR_framework_doc_final_LR-2_1.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- MacKay, S.C.; Smith, A.; Kyle, R.G.; Beattie, M. What influences nurses’ decisions to work in rural and remote settings? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Rural Remote Health 2021, 21, 6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- du Plessis, V.; Beshiri, R.; Bollman, R.D.; Clemenson, M. Definitions of “Rural”, Agriculture and Rural Working Paper Series 28031; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters, M.D. A Comprehensive Taxonomy of Research Designs, a Scaffolded Design Figure for Depicting Essential Dimensions, and Recommendations for Achieving Design Naming Conventions in the Field of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2022, 16, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prengaman, M.P.; Bigbee, J.L.; Baker, E.; Schmitz, D.F. Development of the Nursing Community Apgar Questionnaire (NCAQ): A rural nurse recruitment and retention tool. Rural Remote Health 2014, 14, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qualtrics. Provo, Utah, USA: Qualtrics. 2020. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Thorne, S. Interpretive Description: Qualitative Research for Applied Practice, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; 336p. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Nursing in Canada, 2018: A Lens on Supply and Workforce. 2019. Available online: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/regulated-nurses-2018-report-en-web.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Canadian Association of Rural and Remote Nursing. Canadian Rural and Remote Nursing Practice. 2020. Available online: https://carrn.com/images/pdf/By_the_numbers_CARRN_Infographic.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Graf, A.C.; Nattabi, B.; Jacob, E.; Twigg, D. Experiences of Western Australian rural nursing graduates: A mixed method analysis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2021, 30, 3466–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.G. Rural nursing health services research: A strategy to improve rural health outcomes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, e97–e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulig, J.C.; Kilpatrick, K.; Moffitt, P.; Zimmer, L. Recruitment and Retention in Rural Nursing: It’s Still an Issue! Nurs. Leadersh. Tor. Ont. 2015, 28, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Argent, J.; Lenthall, S.; Hines, S.; Rissel, C. Perceptions of Australian remote area nurses about why they stay or leave: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, M.L.P.; Stewart, N.J.; Kulig, J.C.; Anguish, P.; Andrews, M.E.; Banner, D.; Garraway, L.; Hanlon, N.; Karunanayake, C.; Kilpatrick, K.; et al. Nurses who work in rural and remote communities in Canada: A national survey. Human Resour. Health 2017, 15, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.M.; Hughes, L.S.; Conway, P. A Path to Sustain Rural Hospitals. JAMA 2018, 319, 1193–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Manitoba Sector Profile: Health Care-Job Bank. 2023. Available online: http://www.jobbank.gc.ca/contentjmr.xhtml (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Fleet, R.; Turgeon-Pelchat, C.; Smithman, M.A.; Alami, H.; Fortin, J.P.; Poitras, J.; Ouellet, J.; Gravel, J.; Renaud, M.-P.; Dupuis, G.; et al. Improving delivery of care in rural emergency departments: A qualitative pilot study mobilizing health professionals, decision-makers and citizens in Baie-Saint-Paul and the Magdalen Islands, Québec, Canada. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 62. [Google Scholar]

- McElroy, M.; Wicking, K.; Harvey, N.; Yates, K. What challenges and enablers elicit job satisfaction in rural and remote nursing in Australia: An Integrative review. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2022, 64, 103454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbemba, G.; Gagnon, M.P.; Paré, G.; Côté, J. Interventions for supporting nurse retention in rural and remote areas: An umbrella review. Human Resour. Health 2013, 11, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, H.; Skaczkowski, G.; Gunn, K.M. Addressing the challenges of early career rural nursing to improve job satisfaction and retention: Strategies new nurses think would help. J. Adv. Nurs. 2023, 79, 3299–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchscher, J.E. From Surviving to Thriving: Navigating the First Year of Professional Nursing Practice; Nursing the Future: Saskatoon, SK, Canada, 2012; 288p. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, E.; Plunkett, R.; Goldsmith-Milne, D. Clinical education models in rural practice settings: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pr. 2024, 75, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, D.; Peck, B.; Baker, E.; Schmitz, D. The Rural Nursing Workforce Hierarchy of Needs: Decision-Making concerning Future Rural Healthcare Employment. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, C.; Collett, M.; Thompson, S.C. Tracks to Postgraduate Rural Practice: Longitudinal Qualitative Follow-Up of Nursing Students Who Undertook a Rural Placement in Western Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barry, R.; Kernaghan, L.; Green, E.; Seaman, C.E. The Influence of Connection on Early Career Nurses’ Rural Experiences: A Descriptive Phenomenological Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 8867213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrave, C.; Maple, M.; Hussain, R. An explanation of turnover intention among early-career nursing and allied health professionals working in rural and remote Australia—Findings from a grounded theory study. Rural Remote Health 2018, 18, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, C.; Malatzky, C.; Pardosi, J. What do nurses practising in rural, remote and isolated locations consider important for attraction and retention? A scoping review. Rural Remote Health 2024, 24, 8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Towner, E.C.; Lea, J.; East, L.S. Exploring Experiences of the New Graduate Registered Nurse in Caring for the Deteriorating Patient in Rural Areas: A Qualitative Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2025, 34, 3316–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, E.; Seaman, C.E.; Barry, R.; Lawrence, J.; Skipworth, A.; Sinclair, M. Early career nurses’ self-reported influences and drawbacks for undertaking a rural graduate nursing program. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, K.; Cope, V.; Murray, M. Practice readiness in very remote hospitals: Perceptions of early career and later career registered nurses. Collegian 2023, 30, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Quantitative Survey (N = 77) | Qualitative Interviews (N = 16) |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Current Residence Urban Rural Remote | 4 (5.2%) 53 (68.8%) 20 (26.0%) | 2 (12.5%) 12 (75.0%) 2 (12.5%) |

| Marital Status Single Married/Partnered Divorced/Widowed | 32 (41.6%) 44 (57.1%) 1 (1.3%) | 8 (50.0%) 8 (50.0%) - |

| Years Living in Rural/Remote 5 or less 6–10 11–15 More than 15 Other | 28 (36.4%) 5 (6.4%) 6 (7.9%) 37 (48.0%) 1 (1.3%) | 4 (25.0%) - 1 (6.3%) 10 (62.5%) - |

| Employment Setting Hospital Long Term Care Community Others | 50 (64.9%) 4 (5.2%) 7 (9.1%) 16 (20.8%) | 13 (81.2%) 1 (6.3%) 1 (6.3%) 1 (6.3%) |

| Educational Level LPN Diploma RN Degree Others | 21 (27.3%) 56 (72.7%) - | 5 (31.3%) 10 (62.5%) 1 (6.3%) |

| Health Region Northern Interlake Prairie Mountain Southern Winnipeg Others | 18 (23.4%) 18 (23.4%) 13 (16.8%) 23 (29.9%) 2 (2.6%) 3 (3.9%) | 4 (25.0%) 4 (25.0%) 4 (25.0%) 4 (25.0%) - - |

| Length of License Less than 12 months 13–24 months 25–36 months More than 36 months | 23 (29.9%) 23 (29.9%) 22 (28.5%) 9 (11.7%) | 3 (18.7%) 5 (31.3%) 5 (31.3%) 3 (18.7%) |

| Educational Facility Red River College Polytech Brandon University St. Boniface College University of Manitoba: Fort Gary University College of the North: University of Manitoba University College of the North: LPN Assiniboine Community College: LPN Other | 14 (18.2%) 9 (11.7%) 3 (3.9%) 12 (15.6%) 10 (13.0%) 4 (5.2%) 12 (15.6%) 13 (16.8%) | 3 (18.7%) 2 (12.5%) - 2 (12.5%) 1 (6.3%) - 3 (18.7%) 5 (31.3%) |

| Rank | Variable | Observed Responses (n = 77) | p-Value | χ2 (df = 4) | α-FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | |||||

| 1 | Q9: Having a Positive Workplace Culture | 54 | 0.001 * | 42.73 | 0.003 |

| 2 | Q1: Being Born & Raised in Rural/Remote areas | 51 | 0.001 * | 42.03 | 0.007 |

| 3 | Q12: Having Variety of Clinical Patients | 50 | 0.001 * | 35.27 | 0.011 |

| 4 | Q14: Community Embeddedness | 43 | 0.001 * | 22.45 | 0.014 |

| 5 | Q2: Having Education in Remote/Rural areas | 40 | 0.002 * | 16.68 | 0.018 |

| 6 | Q8: Being Involved in Health Decisions | 39 | 0.002 * | 16.53 | 0.021 |

| 7 | Q11: Having Robust Welcome/Orientation | 39 | 0.004 * | 15.13 | 0.025 |

| 8 | Q4: Having Adequate Compensation | 38 | 0.006 * | 14.56 | 0.029 |

| 9 | Q6: Having Access to Educational Support | 38 | 0.008 * | 13.72 | 0.032 |

| 13 | Q3: Having Affordable/Available Housing | 32 | 0.261 NS | 5.27 | 0.036 |

| Barriers | |||||

| 10 | Q10: Having Unmanageable Workloads | 38 | 0.008 * | 13.72 | 0.036 |

| 11 | Q5: Having Limited Opportunities for Nurse Families | 35 | 0.028 * | 10.91 | 0.039 |

| 12 | Q7: Having Limited Social & Recreational Activities | 35 | 0.037 * | 10.20 | 0.049 |

| 14 | Q13: Having Inadequate Infrastructure | 32 | 0.261 NS | 5.27 | 0.05 |

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Supporting Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Facilitators | ||

| Generalist Role | Patient Variety Being Versatile | “I think being rural, you really are like the jack of all trades.” RNPMRHA-1 “I like the diversity of patients, and I do like the acuity of my unit … it’s ever-changing. There’s always something new going on. I feel like I’m always learning every day.” RNNRHA-2 “I liked being able to come on to a shift and not knowing if we were going to have trauma or if we were going to have just minor treatment stuff all day.” RNNRHA-3 |

| Autonomy | Independent Decision Making Increased Critical Thinking Skills Stabilizing Critical Patients | “The nurses will make a decision and then just update the doctor … 99% of the time they are good with it … send a fax, and great that works. Continue with a treatment plan. We have more autonomy.” LPNIERHA-1 “If someone comes in with an emergency, you as the nurse will have to either find the correct standing orders to go by or make decisions that need to be made even when the doctor is not there.” RNSHRHA-1 |

| Rural Life | Rural Experiences Close Knit Community | “It’s fun living rurally. We’re all generally from the same area. One person’s doing something after work. We can all just go to their house to have like a bonfire or something.” RNSHRHA-4 “I am a rural person. I love being in the middle of nowhere. The great outdoors” RNPMRHA-3 |

| Organizational Culture | Teamwork Tight Knit Hospital Atmosphere Supportive Management | “I feel like we are a tighter-knit community. You get to know the doctors a lot more. It’s a smaller team.” RNSHRHA-3 “I enjoy working with rural doctors, they’re a lot more friendly. Everyone is so friendly there. You felt very welcome. You were supported by your other colleagues.” RNPMHRHA-4 “Everywhere I’ve gone in the North has had such amazing managers that do what they can with what they have it really makes a difference.” RNNHRHA-4 |

| I. Barriers | ||

| Resources | Interdisciplinary Support Diagnostics, Labs, Imaging, Technology | “We have less resources, diagnostics and support in the North. We are always waiting for results from bigger centers.” RNNHRHA-2 “We don’t have healthcare aides or dietary.” RNSHRHA-2 “Like in rural sites, depending on how rural you go, I mean you could be the pharmacist, you could be the lab tech, you could be anything.” RNPMHRHA-3 “We do a lot of communicating via fax, which can be frustrating. Sometimes, it takes days to get a response from a doctor.” LPNIERHA-1 |

| Staffing | Staffing Challenges Use of Agency Nursing | “Having staffing … working double time … being mandated it’s a major challenge of working in a rural site.” RNPMRHA-4 “We are short-staffed we always use agency nurses.” RNSHRHA-3 “The entire nursing team in a remote area is an agency.” RNNHRHA-4 “It does help with staffing. But I would say that there are probably more negatives than positives to using the agency … non-regular staff don’t know what the resident likes, they don’t know how their routines work, they do treatments and meds only.” RNPMRHA-3 |

| Geography | Transport Challenges Weather Distance | “One major barrier right now in rural is transferring people to the city … EMS transport right now is so backlogged.” RNSHRHA-1 “I mean, specifically during the winter, there’s lots of issues even with just staffing, getting nurses to the hospitals can sometimes be very challenging … trying to transport anybody out EMS isn’t going to run in the middle of a snowstorm to an appointment.” RNSHRHA-2 “We are always waiting for flights out, and patients are not always stable.” RNNRHA-3 |

| Expanded Role | Independent Decisions Leadership Roles | “One of the biggest barriers would just be having physicians on-site … putting us into those situations where we sometimes have to do things without them around or make decisions about what they need.” RNSHRHA-2 “I think I was in charge three months out of school or three months past when I got my license, and yeah, it felt very soon. The thing about that is at that time we had barebones staff, we barely had an RN cover each shift and our charge nurses are only our RN’s. So, um, yeah, I felt uncomfortable with being put in that situation.” RNNRHA-2 “You do more in rural. You have a larger scope; you need to take charge of your own learning. It is a huge learning curve.” RNPMRHA-3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Loughery, J.; Gudi, S.K.; Harrigan, T.; Duff, E. Facilitators, Barriers, and Educational Preparedness of Early-Career Nursing Graduates Entering Practice in Rural and Remote Areas: A Mixed-Method Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110410

Loughery J, Gudi SK, Harrigan T, Duff E. Facilitators, Barriers, and Educational Preparedness of Early-Career Nursing Graduates Entering Practice in Rural and Remote Areas: A Mixed-Method Study. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):410. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110410

Chicago/Turabian StyleLoughery, Joanne, Sai Krishna Gudi, Tom Harrigan, and Elsie Duff. 2025. "Facilitators, Barriers, and Educational Preparedness of Early-Career Nursing Graduates Entering Practice in Rural and Remote Areas: A Mixed-Method Study" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110410

APA StyleLoughery, J., Gudi, S. K., Harrigan, T., & Duff, E. (2025). Facilitators, Barriers, and Educational Preparedness of Early-Career Nursing Graduates Entering Practice in Rural and Remote Areas: A Mixed-Method Study. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 410. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110410