Nursing Practice Environment in the Armed Forces: Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

- The Population (P) included nurses (either military or civilian) working in military healthcare settings.

- The Concept (C) referred to the nursing practice environment, encompassing studies that describe NPE characteristics or programs for developing healthy NPEs.

- The context was restricted to military healthcare settings, including primary care, hospital, training, pre-hospital, and combat environments. Studies conducted in a civilian context were excluded.

2.2. Types of Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

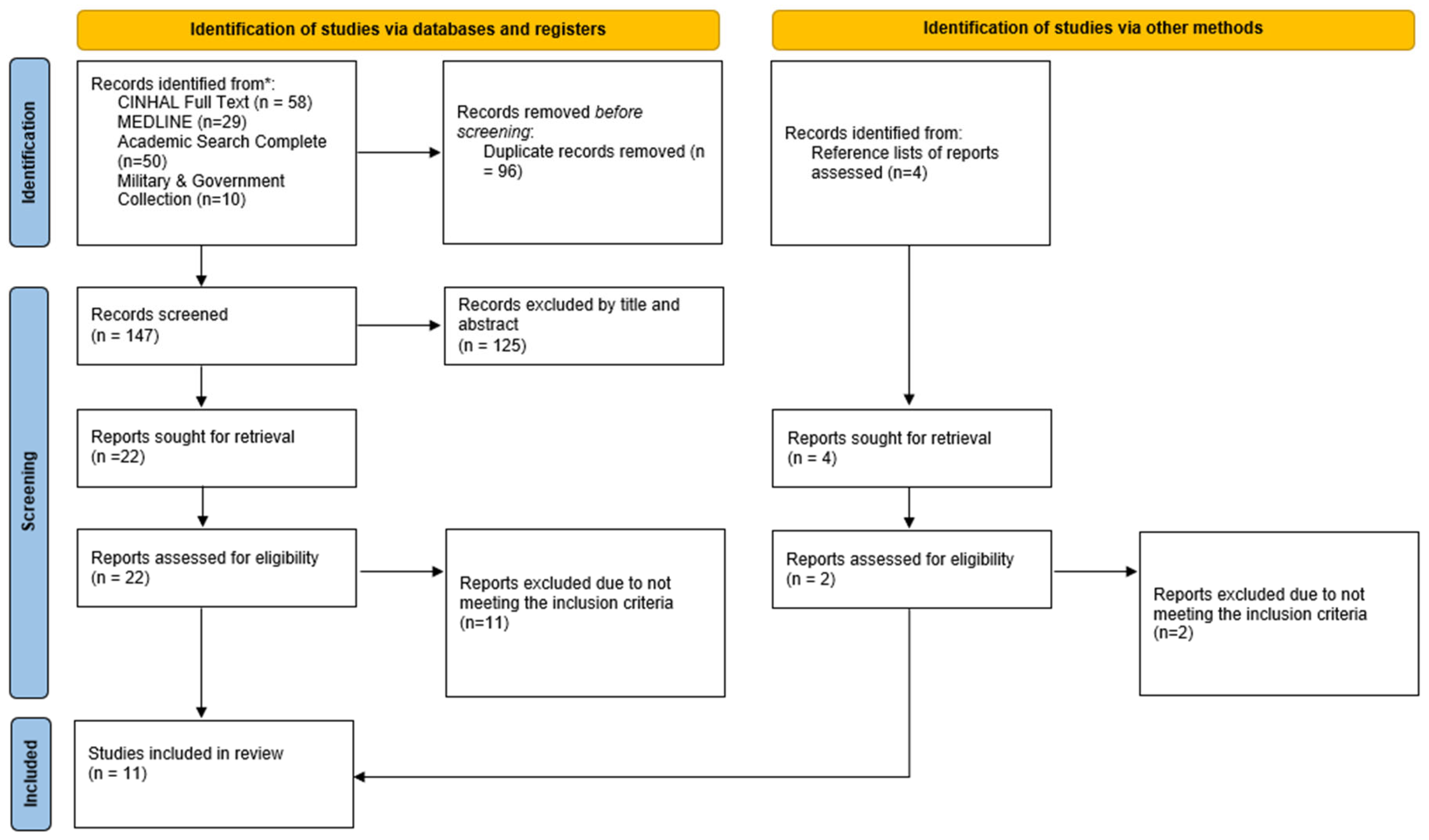

3.1. Source Inclusion

3.2. Characteristics of Included Sources

3.3. Review Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Structural Components

4.1.1. Leadership and Management

4.1.2. Professional Development and Career Progression

4.1.3. Staffing and Resources

4.2. Relational Components

4.2.1. Collaborative Practices

4.2.2. Conflict Management

4.3. Outcome Components

4.3.1. Nurse Well-Being and Job Satisfaction

4.3.2. Nurse Retention

4.3.3. Patient Safety and Quality of Care

4.3.4. Prevention of Complications and Improvements in Health Outcomes

5. Limitations

6. Implications and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paiva-Santos, F.M.; Neves, T.M.A.; Ventura, F.I.Q.S.; Tavares, J.P.d.A.; Amaral, A.F.S. The Influence of the Nursing Practice Environment on Missed Care and Individualized Care. Rev. Enferm. Ref. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H.; Clarke, S.P.; Sloane, D.M.; Lake, E.T.; Cheney, T. Effects of Hospital Care Environment on Patient Mortality and Nurse Outcomes. J. Nurs. Adm. 2008, 38, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrician, P.A.; Shang, J.; Lake, E.T. Organizational Determinants of Work Outcomes and Quality Care Ratings among Army Medical Department Registered Nurses. Res. Nurs. Health 2010, 33, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nightingale, F. Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not; Lusociência: Loures, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lake, E.T. Development of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index. Res. Nurs. Health 2002, 25, 176–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.A.; Laschinger, H.K.S. Authentic Leadership, Performance, and Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Empowerment. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 947–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, M. Magnet Hospitals: Attraction and Retention of Professional Nurses. AORN J. 1983, 38, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.H. Hospital Nurse Staffing and Patient Mortality, Nurse Burnout, and Job Dissatisfaction. JAMA 2002, 288, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, P.; Jesus, É.; Almeida, S.; Costa, P.; Cruchinho, P.; Teixeira, G.; Araújo, B. The Nursing Practice Environment and Job Satisfaction, Intention to Leave, and Burnout Among Primary Healthcare Nurses: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, E.T. The Nursing Practice Environment. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2007, 64, 104S–122S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, I. The Nursing Practice Environment. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013, 50, 1577–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.M.d.; Barbosa, R.L.; Andolhe, R.; Eiras, F.R.C.d.; Padilha, K.G. Nursing Practice Environment and Professional Satisfaction in Critical Care Units. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2017, 70, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Capezuti, E.; Boltz, M.; Fairchild, S. The Nursing Practice Environment and Nurse-Perceived Quality of Geriatric Care in Hospitals. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2009, 31, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutney-Lee, A.; Lake, E.T.; Aiken, L.H. Development of the Hospital Nurse Surveillance Capacity Profile. Res. Nurs. Health 2009, 32, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tei-Tominaga, M.; Sato, F. Effect of Nurses’ Work Environment on Patient Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study of Four Hospitals in Japan. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 13, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiger, P.A.; Raju, D.; Breckenridge-Sproat, S.; Patrician, P.A. Adaptation of the Practice Environment Scale for Military Nurses: A Psychometric Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2219–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrician, P.A.; Olds, D.M.; Breckenridge-Sproat, S.; Taylor-Clark, T.; Swiger, P.A.; Loan, L.A. Comparing the Nurse Work Environment, Job Satisfaction, and Intent to Leave Among Military, Magnet®, Magnet-Aspiring, and Non-Magnet Civilian Hospitals. JONA J. Nurs. Adm. 2022, 52, 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorneles, A.J.A.; Dalmolin, G.d.L.; Andolhe, R.; Magnago, T.S.B.d.S.; Lunardi, V.L. Sociodemographic and Occupational Aspects Associated with Burnout in Military Nursing Workers. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20180350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chihava, T.N.; Fu, J.; Zhang, S.; Lei, L.; Tan, J.; Lin, L.; Luo, Y. Competencies of Military Nurse Managers: A Scoping Review and Unifying Framework. J. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, jonm.13068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, J.; Lu, Y.; Luo, Y. Development and Validation of Professional Competency Scale for Military Nurses: An Instrument Design Study. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.O. Assessing Nurse Manager Competencies in a Military Hospital. Ph.D. Thesis, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Huang, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, F.; Yang, Y.; Luo, Y. Deployment Experiences of Military Nurses: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, P. Military Nursing: Ethical Considerations About Its Statute and Characteristics. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Patrician, P.A.; Loan, L.A.; McCarthy, M.S.; Swiger, P.; Breckenridge-Sproat, S.; Brosch, L.R.; Jennings, B.M. Twenty Years of Staffing, Practice Environment, and Outcomes Research in Military Nursing. Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, S120–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhaan, A.; Brown, M.; McLaughlin, D. Registered Nurses’ Views and Experiences of Delivering Care in War and Conflict Areas: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caggianelli, G.; Cangelosi, G.; Iacono, I.D.; Petrelli, F.; Fiorda, M.; Pettinari, S.; Palomares, S.M.; Marfella, F.; Mancin, S. The Experience of Volunteer Nurses Providing Health and Social Support to Refugees during the War in Ukraine: A Phenomenological Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2025, 8, 100352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, A.; Rizek, J. Caring for Women in an Active War Zone. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 50, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, N. The Humanitarian Crisis in Ukraine. Nurses around the World Can and Should Unite to Help. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2022, 30, e3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama, L.; Amit, I.; Itzhaki, M. Nurses during War: Profiles-Based Risk and Protective Factors. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2025, 57, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Wang, J.; Du, J.; Shi, R. Association Between Psychological Empowerment and Intent to Stay Among Military Hospital Nurses: The Mediating Effects of the Practice Environment and Burnout. J. Adv. Nurs. 2025, 81, 3060–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.M.; Campbell, C.M.; House, S.; Hodson, P.; Swiger, P.A.; Orina, J.; Javed, M.; Pierce, T.; Patrician, P.A. Healthy Work Environment: A Systematic Review Informing a Nursing Professional Practice Model in the US Military Health System. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 80, 3565–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raju, D.; Su, X.; Patrician, P.A. Using Item Response Theory Models to Evaluate the Practice Environment Scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 2014, 22, 323–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiger, P.A.; Loan, L.A.; Raju, D.; Breckenridge-Sproat, S.T.; Miltner, R.S.; Patrician, P.A. Relationships between Army Nursing Practice Environments and Patient Outcomes. Res. Nurs. Health 2018, 41, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangaro, G.A.; Kelley, P.A.W. Job Satisfaction and Retention of Military Nurses: A Review of the Literature. Annu. Rev. Nurs. Res. 2010, 28, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivers, F.; Gordon, S. Military Nurse Deployments: Similarities, Differences, and Resulting Issues. Nurs. Outlook 2017, 65, S100–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, M.A.; Shay, A.; Harris, J.I.; Faller, N.; Usset, T.J.; Simmons, A. Moral Distress and Moral Injury in Military Healthcare Clinicians: A Scoping Review. AJPM Focus. 2024, 3, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, G.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. International Portuguese Nurse Leaders’ Insights for Multicultural Nursing. Int. J. Env. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 12144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P.; Teixeira, G.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. Evaluating the Methodological Approaches of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Bedside Handover Attitudes and Behaviours Questionnaire into Portuguese. J. Health Leadersh. 2023, 15, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G.; Cruchinho, P.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. Transcultural Nursing Leadership: A Concept Analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. Adv. 2023, 5, 100161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.; Sousa, J.P.; Nascimento, T.; Cruchinho, P.; Nunes, E.; Gaspar, F.; Lucas, P. Leadership Development in Undergraduate Nursing Students: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.; Martins, V.; Tomás, M.; Sousa, L.; Nascimento, T.; Costa, P.; Quaresma, G.; Lucas, P. Psychiatric Home Hospitalization: The Role of Mental Health Nurses—A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbut, N.; Miller, M.; Cartwright, J.; Agazio, J.; AmadorGarcia, L. Cultivating Retention: Exploring Transformational Leadership Dynamics in Military Nursing through Qualitative Inquiry. J. Character Leadersh. Dev. 2024, 11, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidenblad, A.; Jansson, J.; Andersson, S.O. Physicians and Nurse’s Perceptions of Leadership in Military Pre-Hospital Emergency Care. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2023, 66, 101237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulat, L.; Cruz, D. Nursing Leadership Styles and Job Satisfaction in a Military Hospital. Int. J. Nov. Res. Dev. 2025, 10, b340–b375. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Thawabiya, A.; Singh, K.; Al-Lenjawi, B.A.; Alomari, A. Leadership Styles and Transformational Leadership Skills among Nurse Leaders in Qatar, a Cross-Sectional Study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 3440–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, C.D.; O’very, D.I.; Bsn, M.A. Leadership Learned Through Action: The Prism of Military Nurse Leadership. Nurse Lead. 2025, 23, 102429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.I.; Cervero, R.M.; Melton, J.L.; Clemons, M.A.; Sims, B.W.; Ma, T.L. Adaptive Leadership and Burnout in Military Healthcare Workers During a Global Health Pandemic. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Z.; Li, B.; Liang, Q.; Liao, S.; Liu, M. Situational Leadership Theory in Nursing Management: A Scoping Review. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, G.M.; Patrician, P.; Steele, N. Comparison of Nurse Burnout Across Army Hospital Practice Environments. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2012, 44, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Healthy Workplaces: A Model for Action: For Employers, Workers, Policy-Makers and Practitioners; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; ISBN 9789241599313. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckenridge-Sproat, S.; Johantgen, M.; Patrician, P. Influence of Unit-Level Staffing on Medication Errors and Falls in Military Hospitals. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2012, 34, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, S.J.; Richter, J.P.; Beauvais, B. The Effects of Nursing Satisfaction and Turnover Cognitions on Patient Attitudes and Outcomes: A Three-Level Multisource Study. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 4943–4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambani, Z.; Kutney-Lee, A.; Lake, E.T. The Nursing Practice Environment and Nurse Job Outcomes: A Path Analysis of Survey Data. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2602–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koesnell, A.; Bester, P.; Niesing, C. Conflict Pressure Cooker: Nurse Managers’ Conflict Management Experiences in a Diverse South African Workplace. Health SA Gesondheid 2019, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Colquhoun, H.; Garritty, C.M.; Hempel, S.; Horsley, T.; Langlois, E.V.; Lillie, E.; O’Brien, K.K.; Tunçalp, Ö.; et al. Scoping Reviews: Reinforcing and Advancing the Methodology and Application. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Khalil, H.; McInerney, P.; Alexander, L.; Tricco, A.C.; Evans, C.; de Moraes, É.B.; Godfrey, C.M.; Pieper, D.; et al. Recommendations for the Extraction, Analysis, and Presentation of Results in Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2023, 21, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vie, L.L.; Whittaker, K.S.; Lathrop, A.D.; Hawkins, J.N. Examining Retention Sentiments and Attrition Among Active Duty Army Medical Officers. Mil. Med. 2024, 189, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structural components | |

| Leadership and management | Supportive [3,31,34,49], transformational [19,31,42] and adaptive leadership [31,42] foster engagement [3,31], teamwork [31,49], and resilience [19]. Ineffective or authoritarian styles increase conflict and dissatisfaction [3,49]. In high-pressure or deployment contexts, situational or autocratic leadership may be required [19]. |

| Professional development and career progression | Career progression, mentorship, and ethical support mechanisms enhance motivation [31,34,57]. |

| Staffing and resources | Adequate nurse-to-patient ratios and resource availability reduce burnout, turnover, and adverse events [16,55,57]. |

| Relational components | |

| Collaborative practices | Interprofessional collaboration and collegial trust improve communication, safety, and morale [3,16,31]. Hierarchical rank structures may constrain dialogue, but structured teamwork mitigates this [19,22]. |

| Conflict management | Multicultural and hierarchical military teams frequently experience conflict, which can be transformed into team learning through reflective and emotionally intelligent leadership [31,58]. Transparent communication and shared mission awareness reinforce followership and role clarity during deployments or readiness exercises [22]. |

| Outcome components | |

| Nurse well-being and job satisfaction | Empowerment, recognition, and supportive supervision reduce burnout and emotional exhaustion, improving engagement and job satisfaction [31,49,57]. |

| Retention and intent to stay | Favorable NPEs and ethical leadership improve retention [30,34,42,57]. However, turnover intentions may not always result in actual exits due to constraints such as deployment cycles and permanent change in station limitations [31,57]. |

| Patient safety and quality of care | Favorable NPEs correlate with lower incidence of falls and medication errors [16,55]. Collaboration, adequate staffing, and moral commitment sustain safe and compassionate care even under crisis or war conditions [31]. |

| Prevention of complications and health gains | Strengthening the nursing practice environment reduces adverse events and promotes measurable health gains for patients, including fewer falls, pressure injuries, and medication errors, as well as improved recovery trajectories and care continuity [16,30,31,56]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inácio, M.; Carvalho, M.; Paulino, A.; Costa, P.; Figueiredo, A.R.; Nunes, E.; Cruchinho, P.; Lucas, P. Nursing Practice Environment in the Armed Forces: Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110394

Inácio M, Carvalho M, Paulino A, Costa P, Figueiredo AR, Nunes E, Cruchinho P, Lucas P. Nursing Practice Environment in the Armed Forces: Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110394

Chicago/Turabian StyleInácio, Mafalda, Maria Carvalho, Ana Paulino, Patrícia Costa, Ana Rita Figueiredo, Elisabete Nunes, Paulo Cruchinho, and Pedro Lucas. 2025. "Nursing Practice Environment in the Armed Forces: Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110394

APA StyleInácio, M., Carvalho, M., Paulino, A., Costa, P., Figueiredo, A. R., Nunes, E., Cruchinho, P., & Lucas, P. (2025). Nursing Practice Environment in the Armed Forces: Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110394