Nurses’ Attitudes and Clinical Judgment on Skin Disinfection Before Subcutaneous Injection: Impact of Setting, Experience, and Normative Beliefs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Investigate whether different healthcare settings influence nurses’ attitudes, practices, and professional norms concerning skin disinfection prior to subcutaneous injections.

- Examine the influence of professional experience on nurses’ attitudes regarding skin disinfection before subcutaneous injection.

- Identify the specific factors (e.g., workplace setting, professional experience, and normative beliefs) that most significantly impact nurses’ attitudes regarding skin disinfection before subcutaneous injection.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Questionnaire Development

2.4. Demographic Characteristics

2.5. Practice and Awareness of Subcutaneous Injection and Disinfection

2.6. Norms Regarding the Practice of Skin Disinfection Before Subcutaneous Injection

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Qualitative Analysis

2.9. Ethics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

References

- Cook, I.F. Sepsis, parenteral vaccination, and skin disinfection. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2016, 12, 2546–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Best Practices for Injections and Related Procedures Toolkit. Safe Injection Global Network (SIGN). 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-best-practices-for-injections-and-related-procedures-toolkit (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Government of Canada. Vaccine Administration Practices: Canadian Immunization Guide. 2023. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-1-key-immunization-information/page-8-vaccine-administration-practices.html (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Forum for Injection Technique UK. The UK Injection and Infusion Technique Recommendations, 4th ed.; Forum for Injection Technique UK (FIT UK): Winnersh, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.diabetesincontrol.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/FIT-UK-Forum.SMALL_.pdf (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Australian Immunisation Handbook; Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care: Canberra, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://immunisationhandbook.health.gov.au/ (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Tandon, N.; Kalra, S.; Balhara, Y.P.S.; Baruah, M.P.; Chadha, M.; Chandalia, H.B.; Prasanna Kumar, K.M.; Madhu, S.V.; Mithal, A.; Sahay, R.; et al. Forum for Injection Technique and Therapy Expert Recommendations, India: The Indian Recommendations for Best Practice in Insulin Injection Technique, 2017. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 21, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, L.J.; Strauss, K.W. The injection technique factor: What you don’t know or teach can make a difference. Clin. Diabetes 2019, 37, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Sumikawa, M.; Sugimori, H.; Yano, R. Factors that affect symptoms of injection site infection among Japanese patients who self-inject insulin for diabetes. Healthcare 2021, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofanidis, D. In-hospital administration of insulin by nurses in Northern Greece: An observational study. Diabetes Spectr. 2017, 30, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, Ö.; Şanlialp Zeyrek, A.; Arslan, S. Subcutaneous injections: A cross-sectional study of knowledge and practice preferences of nurses. Contemp. Nurse 2023, 59, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Takashima, R.; Yano, R. Is skin disinfection before subcutaneous injection necessary? The reasoning of Certified Nurses in Infection Control in Japan. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.; Vostroknutov, A. Why do people follow social norms? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 44, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bicchieri, C.; Lindemans, J.W.; Jiang, T. A structured approach to a diagnostic of collective practices. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingenheimer, J.B. Veering from a Narrow Path: The Second Decade of Social Norms Research. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, S1–S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdurahman, D.; Assefa, N.; Berhane, Y. Parents’ intention toward early marriage of their adolescent girls in eastern Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study from a social norms perspective. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 911648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, J.; Dixit, A.; Green, C.; Akinola, M.; Shaw, B.; Lundgren, R. Addressing social norms for adolescent timing and spacing of pregnancy in low and middle-income countries: Developing a global research agenda. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiGuiseppi, G.T.; Davis, J.P.; Meisel, M.K.; Clark, M.A.; Roberson, M.L.; Ott, M.Q.; Barnett, N.P. The influence of peer and parental norms on first-generation college students’ binge drinking trajectories. Addict. Behav. 2020, 103, 106227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sands, M.; Aunger, R. Determinants of hand hygiene compliance among nurses in US hospitals: A formative research study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J.P. Quality of life and its influence on clinical competence among nurses: A self-reported study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinnick, M.A.; Cabrera-Mino, C. Predictors of Nursing Clinical Judgment in Simulation. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2021, 42, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhaus, M.; Hinson, L.; Rizzo, A.T.; Gregowski, A. Measuring social norms related to child marriage among adult decision-makers of young girls in Phalombe and Thyolo, Malawi. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, S37–S44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Balasi, L.R.; Hazrati, M.; Ashouri, A.; Ebadi, A.; Elahi, N. The status of professional autonomy and its predictors in clinical nurses in Iran. Nurs. Open 2024, 11, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganchuluun, S.; Kondo, A.; Ukuda, M.; Hirai, H.; Wen, J. Factors Related to Nurses’ Professional Autonomy When Caring for Patients with COVID-19 in a University Hospital: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2023, 2023, 1741721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, P. From novice to expert. Am. J. Nurs. 1982, 82, 402–407. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay, M.; Rowbotham, S.; Lim, R.; Peters, S.; Yates, K.; Chater, A. Examining influences on antibiotic prescribing by nurse and pharmacist prescribers: A qualitative study using the Theoretical Domains Framework and COM-B. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.; Hoffman, P.; Robb, F. The need for skin preparation prior to injection: Point—counterpoint. Br. J. Infect. Control 2005, 6, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Watanabe, S. Skin disinfection using hygiene swabs for self-injection of diabetes medications: An overview of the current best practices. Diabetol. Int. 2022, 14, 115–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Burton, C.; Williams, L.; Bucknall, T.; Edwards, S.; Fisher, D.; Hall, B.; Harris, G.; Jones, P.; Makin, M.; McBride, A.; et al. Understanding how and why de-implementation works in health and care: Research protocol for a realist synthesis of evidence. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Bodegom-Vos, L.; Davidoff, F.; de Mheen, P.J.M.-V. Implementation and de-implementation: Two sides of the same coin? BMJ Qual. Saf. 2017, 26, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkerk, E.W.; Tanke, M.A.C.; Kool, R.B.; van Dulmen, S.A.; Westert, G.P. Limit, lean or listen? A typology of low-value care that gives direction in de-implementation. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2018, 30, 736–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K.; Strimling, P.; Gelfand, M.; Wu, J.; Abernathy, J.; Akotia, C.S.; Aldashev, A.; Andersson, P.A.; Andrighetto, G.; Anum, A.; et al. Perceptions of the appropriate response to norm violation in 57 societies. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1481, Erratum in Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gelfand, M.J.; Harrington, J.R.; Jackson, J.C. The Strength of Social Norms Across Human Groups. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 12, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakash, R.A.; Hutton, J.L.; Jørstad-Stein, E.C.; Gates, S.; Lamb, S.E. Maximising response to postal questionnaires—A systematic review of randomised trials in health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | All (n = 992) | Ward Nurse (n = 323) | Outpatient Nurse (n = 328) | Visiting Home Health Nurse (n = 341) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

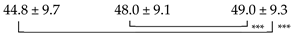

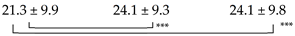

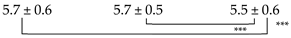

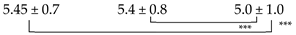

| Age, years | 47.3 ± 9.5 |  | <0.001 *** | ||

| Nursing experience, years | 23.2 ± 9.8 |  | <0.001 *** | ||

| Education | 0.020 *** | ||||

| Professional training college | 822 (83.1%) | 282 (87.3%) | 274 (83.8%) | 266 (78.5%) | |

| Junior college | 55 (5.6%) | 12 (3.7%) | 18 (5.5%) | 25 (7.4%) | |

| Bachelor | 65 (6.6%) | 17 (5.3%) | 16 (4.9%) | 32 (9.4%) | |

| Master or above | 11 (1.1%) | 2 (0.6%) | 1 (0.3%) | 8 (2.4%) | |

| No answer | 36 (3.6%) | 10 (3.1%) | 18 (5.5%) | 8 (2.4%) | |

| Frequency of subcutaneous injection practice | <0.001 *** | ||||

| More than twice a week | 348 (35.1%) | 116 (35.9%) | 177 (54.0%) | 55 (16.1%) | |

| More than once a week | 244 (24.6%) | 91 (28.2%) | 54 (16.5%) | 99 (29.0%) | |

| More than once a month | 164 (16.5%) | 53 (16.4%) | 43 (13.1%) | 68 (19.9%) | |

| More than half a year | 103 (10.4%) | 39 (12.1%) | 19 (5.8%) | 45 (13.2%) | |

| About once a year | 74 (7.5%) | 19 (5.9%) | 22 (6.7%) | 33 (9.7%) | |

| None | 59 (5.9%) | 5 (1.5%) | 13 (4.0%) | 41 (12.0%) | |

| Whether skin disinfection is subcutaneous injection performed before | 0.408 | ||||

| Always | 987 (99.6%) | 321 (99.4%) | 328 (100%) | 338 (99.4%) | |

| Often | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Sometimes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Almost never | 3 (0.3%) | 2 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | |

| Not at all | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Norms | |||||

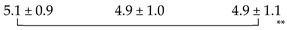

| Personal normative beliefs | 5.0 ± 1.0 |  | 0.045 * | ||

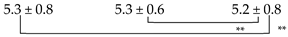

| Normative expectations | 5.3 ± 0.7 |  | 0.045 * | ||

| Empirical expectations | 5.6 ± 0.5 |  | <0.001 *** | ||

| Sanctions (normative expectations) | 5.3 ± 0.9 |  | <0.001 *** | ||

| Category | Description of Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Habituation/Self-Styled Routine | Skipping steps due to over-familiarity with the procedure from long-term self-injection, or establishing a personal, non-standard routine. | 92 | 29.5 |

| 2. Cognitive Impairment | Forgetting or being unable to understand the disinfection procedure due to dementia or age-related cognitive decline. | 70 | 22.4 |

| 3. Perceived Burden/Hassle | Omitting disinfection because the process is perceived as bothersome, troublesome, or a burden in a busy lifestyle. | 50 | 16.0 |

| 4. Lack of Skill or Understanding | Not having yet mastered the self-injection technique or not fully understanding/accepting the necessity of disinfection. | 34 | 10.9 |

| 5. Instructions from Other Healthcare Providers | Being previously instructed by a physician or nurse at another facility that disinfection is unnecessary. | 24 | 7.7 |

| 6. Lack of Supplies/Physical Barriers | Inability to perform disinfection due to physical reasons, such as running out of alcohol swabs, forgetting to prepare them, cost issues, or not having them on hand when outside the home. | 18 | 5.8 |

| 7. Specific Situations/Environments | Omitting disinfection in specific non-hospital settings, such as at home, outdoors, or at the workplace. | 8 | 2.6 |

| 8. Injecting Through Clothing | Injecting directly through clothing to avoid the hassle of exposing the skin. | 6 | 1.9 |

| 9. Impact of Mental Illness | Difficulty performing self-care behaviors due to mental health conditions such as schizophrenia or depression. | 5 | 1.6 |

| 10. Skin Problems/Allergies | Avoiding disinfection to prevent skin irritation, redness, or allergic reactions caused by alcohol swabs. | 5 | 1.6 |

| Total | 312 | 100 |

| CI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | Wald | p-Value | OR | Lower | Upper |

| Clinical Setting | |||||||

| Workplace (Reference: Hospital Ward) | |||||||

| Outpatient Settings | −0.21 | 0.15 | 1.91 | 0.168 | 0.81 | 0.60 | 1.090 |

| Home Care Setting | −0.09 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.574 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 1.24 |

| Professional Experience | |||||||

| Years of Experience | −0.02 | 0.01 | 14.23 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Normative Beliefs | |||||||

| Normative Expectations | 1.06 | 0.11 | 93.45 | <0.001 | 2.88 | 2.32 | 3.56 |

| Empirical Expectations | −0.12 | 0.15 | 0.7 | 0.403 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 1.18 |

| Normative Expectations (Sanctions) | 0.31 | 0.09 | 12.63 | <0.001 | 1.36 | 1.15 | 1.62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoshida, Y.; Ikeno, K.; Takashima, R. Nurses’ Attitudes and Clinical Judgment on Skin Disinfection Before Subcutaneous Injection: Impact of Setting, Experience, and Normative Beliefs. Nurs. Rep. 2025, 15, 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110393

Yoshida Y, Ikeno K, Takashima R. Nurses’ Attitudes and Clinical Judgment on Skin Disinfection Before Subcutaneous Injection: Impact of Setting, Experience, and Normative Beliefs. Nursing Reports. 2025; 15(11):393. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110393

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoshida, Yuko, Kohei Ikeno, and Risa Takashima. 2025. "Nurses’ Attitudes and Clinical Judgment on Skin Disinfection Before Subcutaneous Injection: Impact of Setting, Experience, and Normative Beliefs" Nursing Reports 15, no. 11: 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110393

APA StyleYoshida, Y., Ikeno, K., & Takashima, R. (2025). Nurses’ Attitudes and Clinical Judgment on Skin Disinfection Before Subcutaneous Injection: Impact of Setting, Experience, and Normative Beliefs. Nursing Reports, 15(11), 393. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15110393