Understanding the Impact of the Nurse Manager’s Vocation for Leadership on the Healthcare Workplace Environments in Mexico: A Grounded Theory Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Vocation and Nursing

1.2. Leadership and Nursing

1.3. Workplace Environment and Nursing

1.4. Hypothesis and Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Techniques

2.2. Population, Sample, and Sampling

- -

- Have a minimum of 5 years’ experience as a manager in their working environment.

- -

- Have at least some professional training, specialization, and/or postgraduate degree in nursing.

- -

- Currently holding the position of nurse manager (understood as any formally designated management responsibility).

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5. Rigor and Reliability

- -

- The researcher returned to the informants twice during the data collection process to confirm the findings and review specific data. This was done to verify information that resulted in findings acknowledged by the informants, drawing from their experiences, feelings, and thoughts.

- -

- In the selection of informants, specific criteria were applied, focusing exclusively on nurse managers in the hospital environment. Simultaneously, the literature search was adjusted to the management context.

- -

- The interviews were transcribed word-for-word to maintain the veracity of the answers. The analysis of the information was carried out by the “Principal Investigator” and then shown to two other expert investigators, to assure the same or similar conclusions, who had similar perspectives.

- -

- At the end of the analysis of the information, a triangulation with two expert researchers on the subject was sought, to visualize the reality found in the information, sharing the perspective of the researchers, based on the information.

3. Results

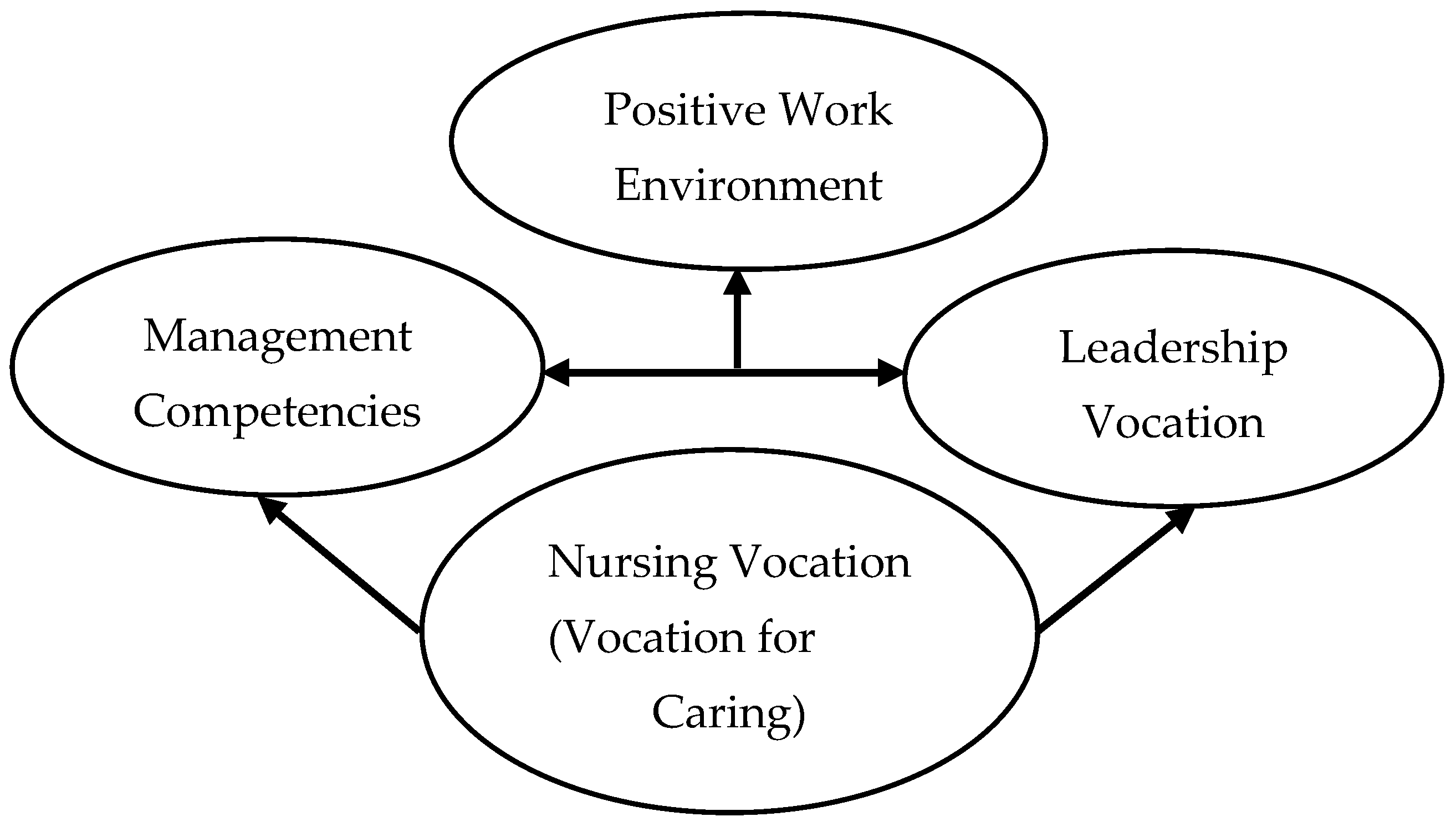

Presentation of the Comprehensive Model

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tello, G.R. Power and Insertion of Nurses in Hospital Management. Las Mercedes Regional Teaching Hospita—Chiclayo 2019. Ph.D. Thesis, Santo Toribio De Mogrovejo Catholic University Graduate School, Lambayeque, Peru, 2023. Available online: https://repositorioslatinoamericanos.uchile.cl/handle/2250/6390947 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Zhang, F.; Peng, X.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; He, J.; Guan, C.; Chang, H.; Chen, Y. A caring leadership model in nursing: A grounded theory approach. J. Nurs. Manag. 2022, 30, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lillo-Crespo, M.; Riquelme-Galindo, J.; De Baetselier, E.; Van Rompaey, B.; Dilles, T. Understanding pharmaceutical care and nurse prescribing in Spain: A grounded theory approach through healthcare professionals’ views and expectations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0260445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. Nursing as a vocation. Nurs. Ethics 2002, 9, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallard Munoz, I.E. Evoking the nursing vocation. Conecta Lib. Mag. 2019, 3, 35–44. Available online: https://revistaitsl.itslibertad.edu.ec/index.php/ITSL/article/view/113 (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Ponton, R.; Brown, T.; McDonnell, B.; Clark, C.; Pepe, J.; Deykerhoff, M. Vocational perce ption: A mixed-method investigation of calling. Psychol.-Manag. J. 2014, 17, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Ortega, R. Nursing Praxis: A Vocation with Axiological and Humanist Sense. Sci. Mag. 2018, 3, 348–361. Available online: http://www.indteca.com/ojs/index.php/Revista_Scientific/article/view/243 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Dobrow, S.R.; Tosti-Kharas, J. Called: The development of a measure of scale. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callio, H.; Kangasniemi, M.; Hult, M. Registered nurses’ perceptions of having a calling to nursing: A mixed method study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1473–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, C.S. The Vocation of Being a Nurse. Vinculando Mag. 2019, 17. Available online: http://vinculando.org/articulos/la-vocacion-de-serenfermera.html (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Antonakis, J.; Day, D. The Nature of Leadership, 3rd ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dongen, L.J.C.; Hafsteinsdóttir, T.B. Leadership of PhD-prepared nurses working in hospitals and its influence on career development: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2022, 31, 3414–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, O. Leadership Style of Directors; San Marcos: Lima, Peru, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, A. Directive Leadership; Lime: Saint Mark, FL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, D.C.Q.; Mansilla, D.C.; Jaque, R.A.L.; Vallejos, G.G.; Nachar, A.L.; Guiñez, D.M. Perception of hospital and primary health care nurses about Nursing leadership. Culture of care. J. Nurs. Humanit. 2020, 58, 67–78. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/111386/1/CultCuid58-67-78.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Bass, B.; Avolio, B.; Jung, D. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the MLQ. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 72, 441–462. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, D.E. Human resource management and industrial relations. J. Manag. Stud. 1987, 24, 503–521. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1987.tb00460.x (accessed on 10 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Cummings, G.G.; Tate, K.; Lee, S.; Wong, C.A.; Paananen, T.; Micaroni, S.P.M.; Chatterjee, G.E. Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 85, 19–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trastek, V.F.; Hamilton, N.W.; Niles, E.E. Leadership models in health care-a case for servant leadership. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bass, B. Two Decades of Research and Development in Transformational Leadership. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 1999, 8, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.P.; Moore, W.M.; Moser, L.R.; Neill, K.K.; Sambamoorthi, U.; Bell, H.S. The Role of Servant Leadership and Transformational Leadership in Academic Pharmacy. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2016, 80, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, Y. Leadership in Organizations; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008; pp. 331–348, 352–354. Available online: http://biblioteca.udgvirtual.udg.mx/jspui/handle/123456789/1965 (accessed on 18 November 2023).

- Castillo Alarcon, M.R. The Organizational Climate of a Commercial Company in the Central Zone of Tamaulipas, Mexico. Case study: MULTI. Ciudad Victoria. Master’s Thesis, Autonomous University of Tamaulipas, Victoria, Mexico, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Segredo Pérez, A.M.; García Milián, A.J.; López Puig, P.; León Cabrera, P.; Perdomo Victoria, I. Systemic approach to organizational climate and its application in public health. Rev. Cub. Sal. Públ. 2015, 41–46. Available online: http://www.revsaludpublica.sld.cu/index.php/spu/article/view/300/307 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Sánchez Jacas, I.; Brea López, I.L.; De La Cruz Castro, M.C.; Matos Fernández, I. Motivation and leadership of the staff of the general services subsystem in two maternity hospitals. Med. Sci. Mail 2017, 1–7. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/pdf/ccm/v21n2/ccm09217.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Thanks, T.J.H. Diagnostic study of transformational leadership in nursing staff working in Mexican public hospitals. Cimexus 2019, 13, 89–109. Available online: https://cimexus.umich.mx/index.php/cim1/article/download/292/231 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Salguero Barba, N.G.; Garcia Salguero, C.P. Influence of leadership on the organizational climate in higher education institutions. Bol. Redipe 2017, 6, 135–149. Available online: https://revista.redipe.org/index.php/1/article/view/230 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Alvarado Limaylla, D.A.; Cafferatta Berru, B.A. Relationship of the Leadership Style of the Bosses with the Organizational Climate of the Administrative Staff in the ANDAHUASI Company. Master’s Thesis, USMP, Santa Anita, Peru, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Argüelles, R.; Cobos-Díaz, P.A.; Figueroa-Varela, M.R. Evaluation of the organizational climate in a rehabilitation and special education center. Rev. Cuba Public Health 2015, 41, 593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Kopelman, R.E.; Brief, A.P.; Guzzo, R.A. The role of climate and culture in productivity. In Organizational Climate and Culture; Schneider, B., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Permarupan, P.Y.; Al-Mamun, A.; Saufi, R.A.; Zainol, N.R.B. Organizational climate on employees’ work passion: A review. Can. Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ángel-Salazar, E.; Fernández-Acosta, C.; Santes-Bastián, M.; Fernández-Sánchez, H.; Zepeta-Hernández, D. Organizational climate and job satisfaction in health workers. Univ. Nurs. 2020, 17, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracamonte, L.M.; Gonzalez-Argote, J. Leadership style in heads of nursing services and its relationship with job satisfaction. Ref. Sci. J. MenteClara Found. 2002, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentin Tuburcio, L.Y. Factors Associated with Nursing Vocation in Students. Bachelor’s Thesis, San Pedro University, Huacho, Peru, 2021. Available online: http://www.repositorio.usanpedro.edu.pe/handle/20.500.129076/19717 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Lozano-González, E.O.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, R. Vocation and teacher training in the area of health: Impulses for transformation. Univ. Teach. Mag. 2022, 23, 23–43. Available online: https://revistas.uis.edu.co/index.php/revistadocencia/article/view/13141 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; Volume 3, pp. 24–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, F.D.; Beck, C.T. Nursing Research Foundations for the Use of Evidence in Nursing Practice, 9th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S.J.; Bogdan, R. Introduction to Qualitative Methods, 1st ed.; Paidos: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1984; Available online: https://asodea.files.wordpress.com/2009/09/taylor-sj-bogdan-r-metodologia-cualitativa.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Ministry of Health [SESA]. Regulations of the General Health Law on Research for Health [Internet]. Mexico. 2014. Available online: http://www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/cdi/nom/compi/rlgsmis.html (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Ndanu, M.C. Mixed Methods Research: The Hidden Cracks of the Triangulation Design. Gen. Educ. J. 2015, 4, 46–67, Erratum in Mt. Meru Univ. Res. 2015, 2, 46–67. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue, T.; Punch, K. Qualitative Educational Research in Action: Doing and Reflecting; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Souza Silva, R. Nursing leadership in palliative care. Electron. Mag. 2021, 2, 27–29. Available online: https://publicacio-nes.unpa.edu.ar/index.php/boletindeenfermeria/article/download/785/817 (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Labrague, L.J.; Al Sabei, S.; Al Rawajfah, O.; AbuAlRub, R.; Burney, I. Authentic leadership and nurses’ motivation to engage in leadership roles: The mediating effects of nurse work environment and leadership self-efficacy. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 2444–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phenomenon | Category |

|---|---|

| Management development | Nursing Vocation (Vocation for Caring) |

| Management Competencies | |

| Leadership and management generation | Leadership Vocation |

| Leadership and the work environment | Positive Work Environment |

| Participant | Gender | Basic Training | Postgraduate Training | Professional Experience | Work Area | Type of Contract |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master of Nursing Services Administration | 16 years | Emergency | Permanent |

| 2 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Public Health | 16 years | Emergency | Permanent |

| 3 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Public Health | 17 years | Operating Theatre | Permanent |

| 4 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing and Midwifery | Master’s Degree in Administration of Health Institutions | 18 years | Intensive Care Unit | Permanent |

| 5 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | ----- | 15 years | Internal Medicine | Permanent |

| 6 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Skill in administration | 37 years | Permanent | |

| 7 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | ----- | 18 years | Intensive Care Unit | Permanent |

| 8 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Surgical Nursing Specialist | 36 years | Internal Medicine | Permanent |

| 9 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Administration of Nursing Services | 27 years | Emergency | Permanent |

| 10 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | ----- | 37 years | Operating Theatre | Permanent |

| 11 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Surgical Nursing Specialist | 30 years | Internal Medicine | Permanent |

| 12 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Administration of Nursing Services | 25 years | Emergency | Permanent |

| 13 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | ----- | 17 years | Operating Theatre | Permanent |

| 14 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Public Health | 16 years | Emergency | Permanent |

| 15 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Public Health | 17 years | Operating Theatre | Permanent |

| 16 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | ----- | 18 years | Intensive Care Unit | Permanent |

| 17 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Surgical Nursing Specialist | 36 years | Internal Medicine | Permanent |

| 18 | Female | Bachelor of Nursing | Master in Administration of Nursing Services | 27 years | Emergency | Permanent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yañez-Lozano, A.; Lillo-Crespo, M. Understanding the Impact of the Nurse Manager’s Vocation for Leadership on the Healthcare Workplace Environments in Mexico: A Grounded Theory Approach. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1224-1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020093

Yañez-Lozano A, Lillo-Crespo M. Understanding the Impact of the Nurse Manager’s Vocation for Leadership on the Healthcare Workplace Environments in Mexico: A Grounded Theory Approach. Nursing Reports. 2024; 14(2):1224-1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020093

Chicago/Turabian StyleYañez-Lozano, Angeles, and Manuel Lillo-Crespo. 2024. "Understanding the Impact of the Nurse Manager’s Vocation for Leadership on the Healthcare Workplace Environments in Mexico: A Grounded Theory Approach" Nursing Reports 14, no. 2: 1224-1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020093

APA StyleYañez-Lozano, A., & Lillo-Crespo, M. (2024). Understanding the Impact of the Nurse Manager’s Vocation for Leadership on the Healthcare Workplace Environments in Mexico: A Grounded Theory Approach. Nursing Reports, 14(2), 1224-1235. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep14020093