1. Introduction

Like many other countries, the Netherlands faces an increasing shortage of nurses. There are many reasons for this discrepancy between the supply and demand for nurses. One important reason is that nurses frequently leave the profession to work in another profession or industry. This creates a hidden reserve of nurses, i.e., workers with a diploma as a (registered) nurse who are not employed as a nurse or are not working in the healthcare sector. This hidden reserve can take different forms. It includes workers with a nursing diploma who are employed in another occupation in another industry, those who work fewer hours as a nurse than their full potential (part-time workers), and those who are not employed either because they are unemployed or out of the labor force (for example because they are in education). In the Netherlands, this hidden reserve of nurses is substantial [

1]. Employment opportunities may vary between regions resulting in differences in pull factors that may tempt nurses to switch to a different industry or profession. The effect of push factors (for example job conditions in healthcare that are considered poor by nurses) interact with pull factors. If both factors are strong, the tendency to leave the healthcare sector will be large. Furthermore, regional differences in cost of living, mostly due to differences in housing prices, may cause nurses to be less likely to reside in some high-cost areas. Consequently, regional differences in the size of the hidden reserve of nurses may emerge.

Prior research has shown that the labor market of nurses is indeed very local [

2,

3,

4]. According to Kovner et al. [

4], both mobility and commuting among nurses are limited. The area of living, school, and the prospective workplace are typically within the same geographical area and at distances that are commutable [

3,

4]. These observations entail important policy consequences for training, attracting, and retaining nurses. Kovner et al. [

4] emphasize the critical role of geographic positioning and the capacity of nursing schools. Similarly, Dahal et al. [

3] argue that gaining insight into the distribution of nurses and their residential patterns is crucial for effective policymaking and strategic workforce planning.

There is limited evidence on the magnitude and the regional variance in the hidden reserve of nurses. Most of the evidence focuses on the available reserve of military and civilian nurses [

5], emergency nurses [

6], and on the potential of migrant nurses [

7]. One study using a survey of registered nurses in the US found that in 2017, 61% of the registered nurses worked full-time as a nurse, while 17.3% were not working in nursing [

8]. This study also found geographical variation in the hidden reserve of nurses, with more nurses working in other professions in more populous states.

In the Netherlands, the projected shortage of bachelor-trained nurses for 2023 was estimated to range between 5800 and 6000 full-time equivalents (fte) [

9]. For vocationally trained nurses, the estimated shortage was between 8300 and 8700 fte, and between 9700 and 10,100 fte for nurse assistants [

9]. Somers et al. (2023) found that the hidden reserve of trained nurses who do not work in the healthcare sector exceeds these shortages. For bachelor-trained nurses, the hidden reserve comprises more than 15,000 persons (20.3 percent of all trained nurses), for vocationally trained nurses almost 9000 persons (14 percent), and more than 16,000 (17.4 percent) for nurse assistants [

1]. The hidden reserve of part-time working nurses is also substantial and exceeds the total shortage. Increasing all part-time contracts to full-time (36 h in the Netherlands) would result in 11,000 fte for both bachelor- and vocational-trained nurses and 22,000 fte for nurse assistants [

1].

One of the reasons for this large hidden reserve could be the perceived working conditions in nursing occupations. In 2013, Aiken et al. [

10] published a study on the working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe, including the Netherlands. Nurses in all countries report that they are dissatisfied with important working conditions and many of them consider leaving their jobs [

10]. However, significant variations exist between countries. The Netherlands has a relatively low percentage of dissatisfied nurses [

10]. Similar to nurses in other countries, Dutch nurses experience limited opportunities for professional development, strained relations with management, and a lack of nurse leadership at the top of healthcare organizations [

10]. Although the staff mix and the nurse-to-patient ratios vary substantially between countries, nurses in all countries are dissatisfied with their work conditions and the consequences this has for the quality of patient care [

10]. Work conditions also vary within countries. Previous research in the Netherlands, for example, shows differences in autonomy and social support between intensive and non-intensive care nurses [

11]. Moreover, this variation between non-intensive and intensive care departments within hospitals is larger than the variation between intensive care departments of different hospitals. Variations may also occur in other healthcare sectors. For example, specialized (diabetes) nurses experience relatively high levels of autonomy compared to nurses in other healthcare settings [

12]. Variations may also exist within a country between regions. Dissatisfaction about work conditions appears to be a structural problem as a recent study shows that the work conditions have not changed very much [

13].

In this study, we are especially interested in differences in the volume and composition of hidden reserves across regions. Available capacity influences work conditions and quality of care both directly and indirectly. The direct influence concerns the capacity available to get the “work done”. Indirectly, it concerns the amount of slack available to coordinate activities by the nurses themselves and to absorb uncertainty about the amount of work [

14,

15].

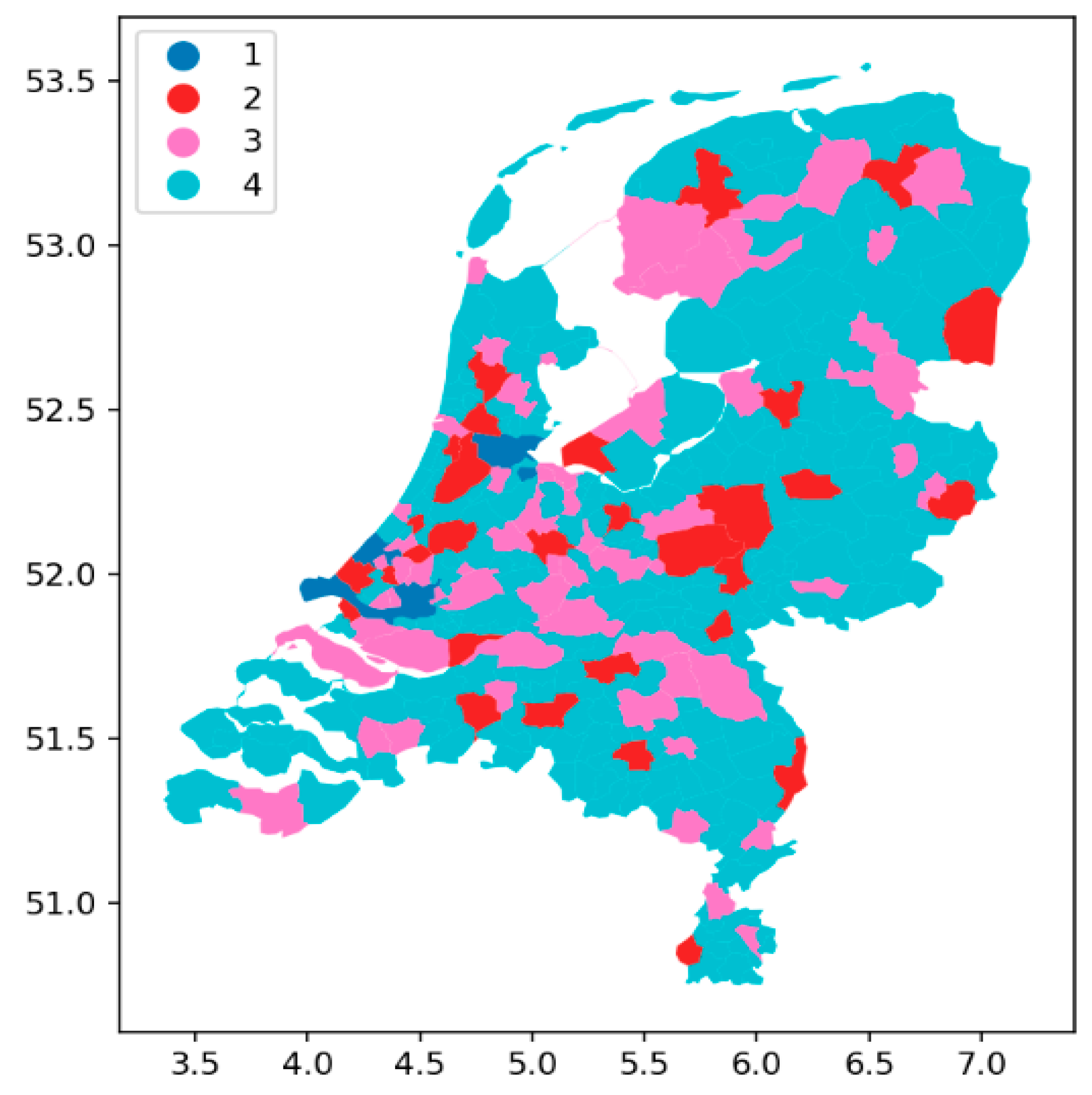

In this study, we analyze the extent of spatial variations in hidden reserves across different categories of nurses in the Netherlands. If geographic disparities in hidden reserves are present, it is important to understand these differences. Policies aimed at incentivizing nurses to re-enter or remain in the healthcare sector need to take the regional context into account. Implementing regionally tailored policies alongside national initiatives is essential for mitigating nurse shortages. We focus on the hidden reserve in the Netherlands and examine how different push and pull factors relate to the spatial distribution of the hidden reserve. We define the hidden reserve of nurses as the number of nurses who are trained as a nurse, nurse assistant, or healthcare assistant, but are not employed in the healthcare sector (anymore). We use registry data from the Netherlands to estimate the size of the hidden reserve at the municipality level in the Netherlands. The Dutch registry data distinguishes between four types of nursing degrees:

Bachelor-trained nurse (BN), EQF level 6;

Vocational-trained nurse (VN), EQF level 4;

Nurse assistant (NA), EQF level 3;

Healthcare assistant (HA), EQF level 2.

(The Dutch program names are: (1). hbo verpleegkundige, (2). mbo verpleegkundige, (3). verzorgende mbo niveau 3, (4). helpende mbo niveau 2.)

EQF levels refer to the European Qualification Framework (EQF), established by the Bologna Process to ensure transparency and transferability of qualifications in Europe [

16]. In the Netherlands, there are no nurses registered at the EQF levels 1 and 5. EQF level 1 refers to workers who support a patient and/or have experience as a patient. In The Netherlands, these support staff are not considered healthcare professionals. EQF level 5 nurse degrees do not exist in the Netherlands, although nurses are offered courses where they in fact attain this level. However, to manage the complexity of the national nurse function system from which the salary scales are derived the EQF level 5 is not a formally distinguished level. However, employers have the flexibility to reward nurses who succeed in obtaining extra diplomas on top of what is formally required for a certain level. In the Dutch case, and in our study, this means that EQF 5 nurses are included as EQF 4.

We describe how the size of the hidden reserve within municipalities or regions relates to different push and pull factors. Pull factors attract nurses to other occupations or to work as a nurse outside their own municipality or region. We expect that more outside career options increase the likelihood that individuals choose professions outside nursing. Pull factors related to outside career options include the availability of jobs with higher salaries or better career prospects. Pull factors also include circumstances associated with big city problems, like high housing costs. As proxies for these pull factors, we use the population size, the average income level of municipalities, and the distance to a region with a shortage of nurses. High hidden reserves and low shares of nurses in the population signal the effect of pull factors.

Push factors include nurse- and/or employer-related work, salary, and career conditions. If these are not considered favorable, these factors “push” nurses out of their jobs or out of healthcare. Even if nurses do not leave healthcare, push factors result in high turnover costs if nurses frequently change employers, especially in big cities [

2]. A high turnover can be considered as a symptom that work conditions for nurses are dissatisfying [

2].

This paper is structured as follows. First, we discuss the data and methods that we use to describe the spatial characteristics of trained nurses. Next, we present national-level results and figures at the municipal level. Given that many nurses work in municipalities different from where they reside but within a commutable distance, we also describe the regional situation. Specifically, we focus on the three largest cities in the Netherlands (Amsterdam, The Hague, and Rotterdam) and their surrounding areas, defined by the commutable distance. In the discussion section, we interpret the results and address the limitations of our methodological approach.

4. Discussion

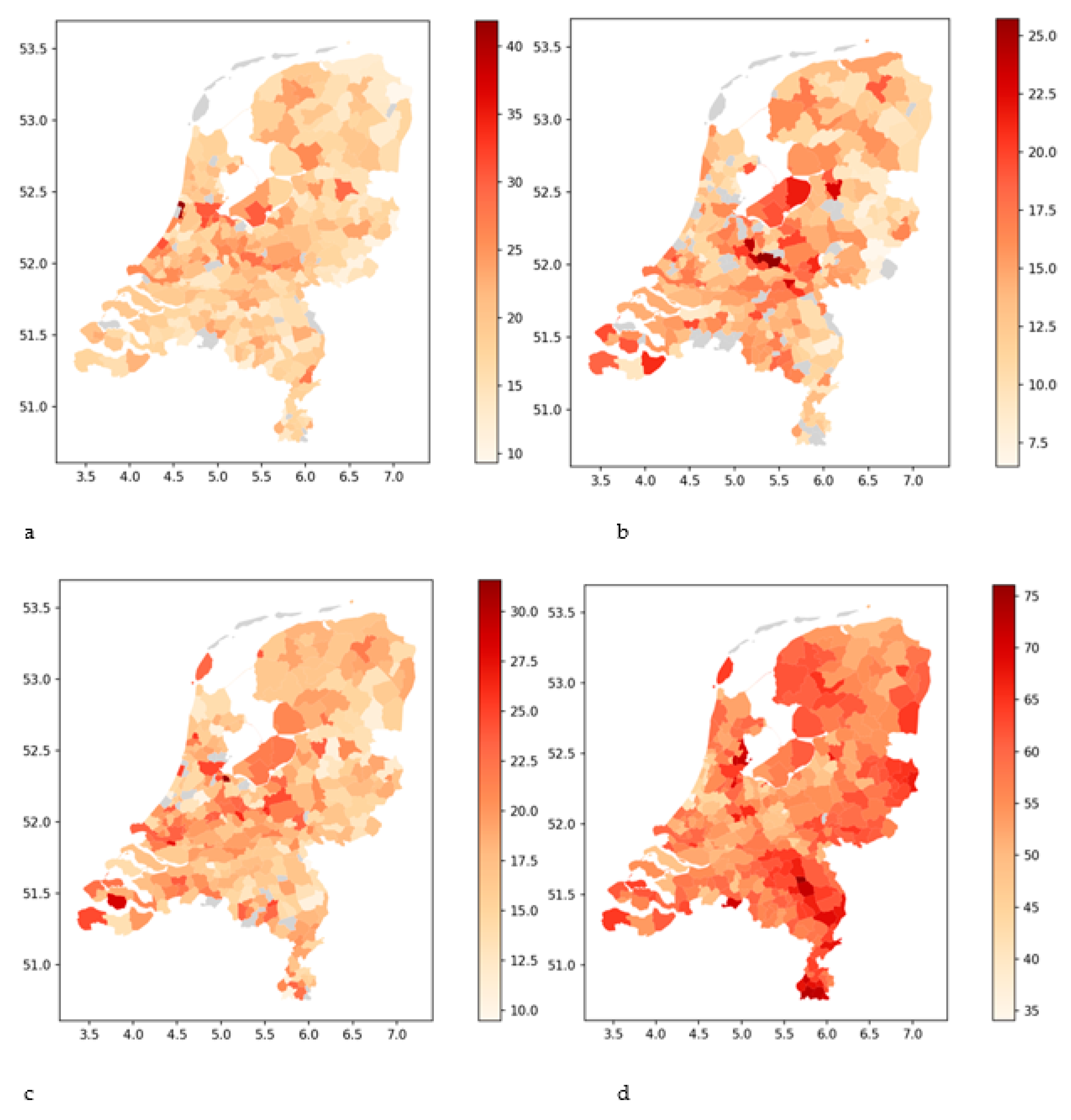

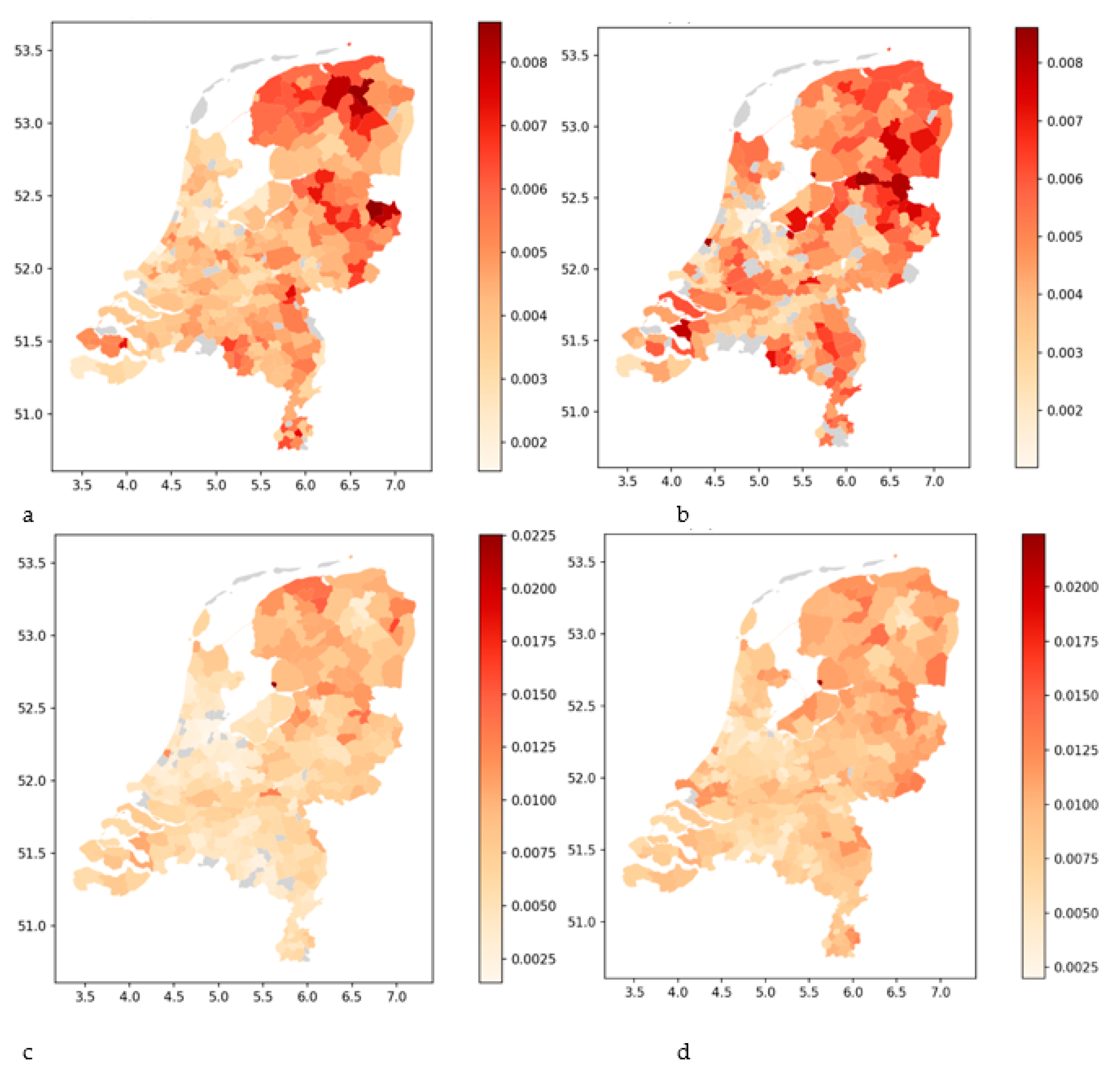

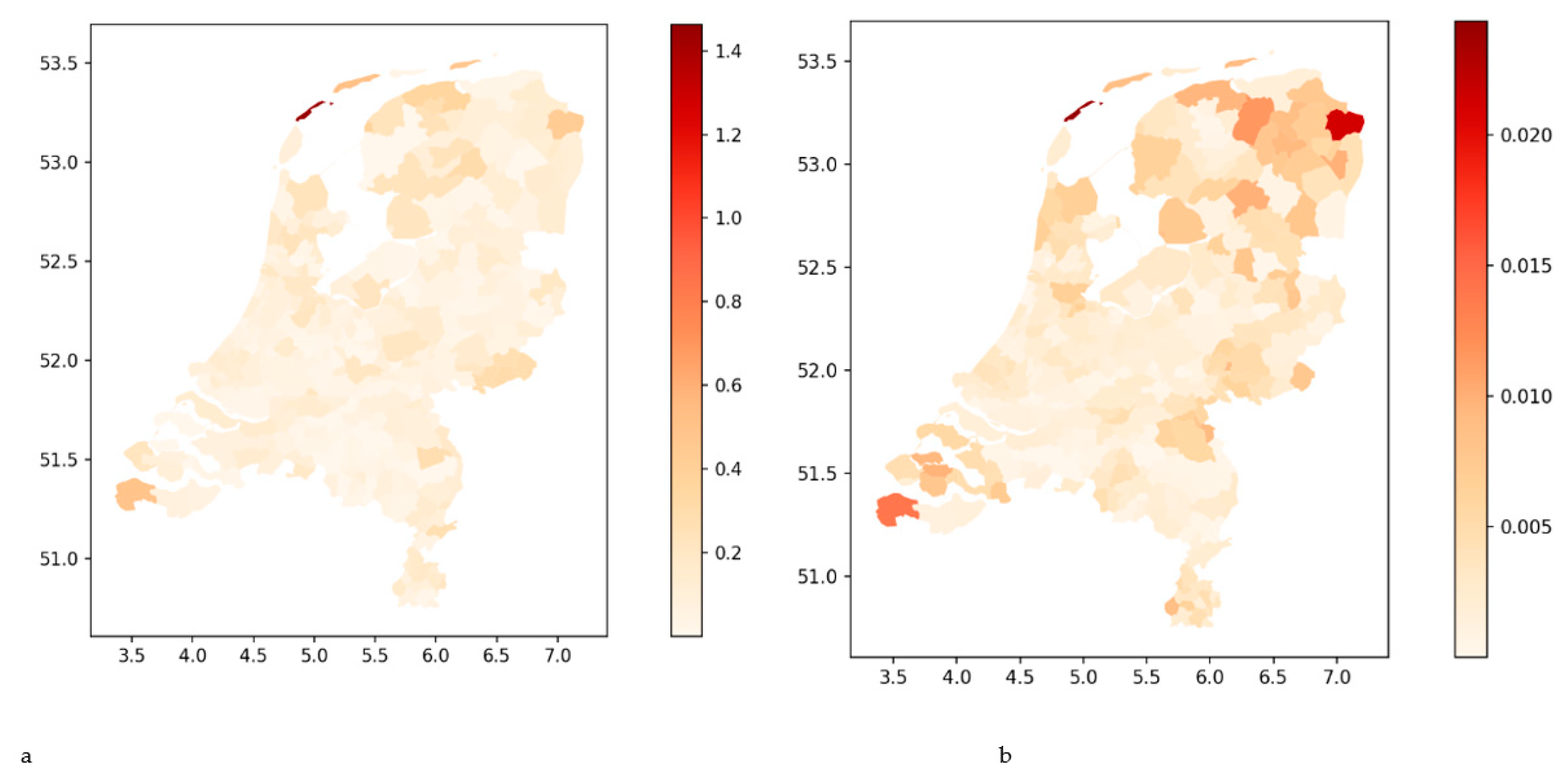

Our analysis showed that there is a significant geographic variation in the size of hidden reserves and the share of trained nurses relative to the total population size of a municipality. In addition to the geographic variation, there is also variation across the different nurse categories.

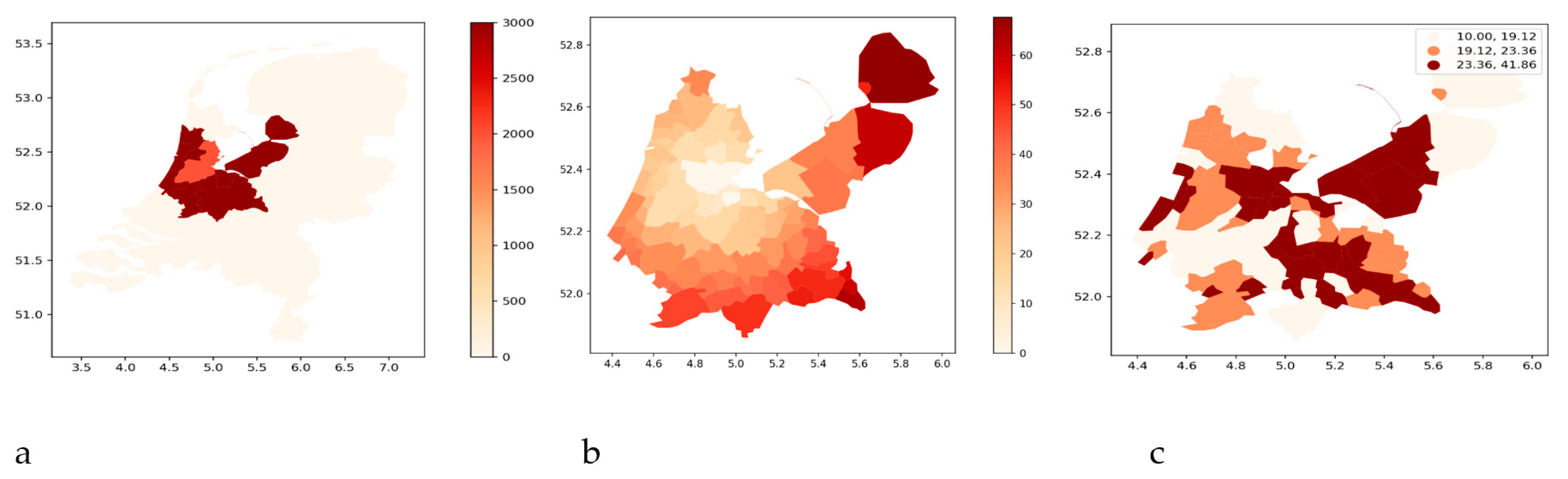

The western region of the Netherlands, including cities such as Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam, and several 2nd tier municipalities, known as the “Randstad” or the Dutch metropolitan area, exhibits varying levels of hidden reserves across all nurse categories. However, predominantly among healthcare assistants, there are high hidden reserves. Despite being highly urbanized, this area has a low proportion of trained nurses relative to the total population, across all nurse categories. The only exception is some areas in the west, which have a medium proportion of vocationally trained nurses. In the Dutch metropolitan area, there is segregation between first-tier municipalities and several second-tier municipalities and their surroundings. The same phenomenon is visible in a number of 2nd tier municipalities outside the metropolitan west, but less prominently. This suggests that the 1st tier and some 2nd tier municipalities depend on nurses from surrounding municipalities which have higher shares of trained nurses relative to the population compared to the 1st tier municipalities, but lower compared to the rest of the Netherlands. Because nurse labor markets are local [

2,

3,

4], longer commuting distances are unlikely. Pulling nurses to metropolitan areas from surrounding areas would likely require significant incentives.

Our findings also clearly show a negative association between the hidden reserve and the distance from the metropolitan centers. The hidden reserves are larger within metropolitan areas than outside them. Furthermore, we observe a negative association between the hidden reserve and the mean individual income in an area. These findings suggest that individuals with a nurse qualification, who earn an average income, are more likely to be pushed out of the metropolitan areas where the cost of living—and especially the cost of housing—is higher. Workers with a nurse qualification who remain in the metropolitan area are more inclined to leave the nursing profession for better-paying jobs in other industries, thereby contributing to the hidden reserve. Additionally, the relatively smaller hidden reserve outside metropolitan areas suggests that it may be more challenging to incentivize nurses from these areas to relocate to metropolitan areas with higher living costs.

Our findings raise questions about the feasibility of policies aimed at encouraging nurses to reside and work, particularly in first municipalities. The spatial associations presented in this paper do not permit causal inferences or definitive conclusions about the push and pull factors that may explain them. Nurses may be pushed out of a healthcare organization, for example, because of work conditions. If there are numerous local opportunities to work in other healthcare organizations, turnover rates will increase, resulting in higher concentrations of nurses in these local and nearby organizations. This will lead to extra costs for organizations in metropolitan areas to attract nurses and retain them. Alternatively, nurses may choose to leave the healthcare sector and seek employment in other industries. Notably, the hidden reserve of bachelor-trained nurses in the three major cities is significant compared to the surrounding municipalities. As all these municipalities are part of a metropolitan area, and if working as a nurse in a big city is considered less attractive, nurses have enough alternatives to work in the surrounding cities. When there are not many options to work in healthcare locally, push factors will result in nurses leaving the healthcare sector or opting out by an accumulation of dissatisfaction, stress, and sickness absence. Hence, the effects of push factors may vary between metropolitan and rural areas.

However, do the big cities have the same push and pull factors? The hidden reserves, especially those of bachelor-trained nurses and healthcare assistants, differ between the three major cities. It is challenging to speculate about the differences in push factors between these cities based on the existing literature and our findings. However, insights from the urban geography literature suggest that pull factors are closely tied to the size and function of a city, where the number and variety of job opportunities generally increase with the size of the city [

19]. This is also the rationale for dividing Dutch municipalities into a hierarchy of four tiers, with tier 1 cities offering not only more jobs but also a greater diversity of job types. The number of job types in these cities increases the likelihood of attracting nurses to alternative employment opportunities, potentially explaining the differences in hidden reserves between the three major cities and the rest of the Netherlands. Nonetheless, this explanation falls short of explaining the differences among these three cities, unless we delve deeper into their specific functions and job markets.

In addition to job opportunities, the three cities also differ in other factors, especially in average personal income and their relationship with hidden reserves in the surrounding municipalities. According to data from Statistics Netherlands, the average personal incomes (in 2020) vary substantially and are as follows: Amsterdam: EUR 32,400, The Hague: EUR 27,800, and Rotterdam: EUR 26,000 [

18]. The Pearson correlation coefficients presented in

Table 4 indicate that these differences align with variations in the hidden reserves for nursing professions. However, it is important to interpret these patterns with caution as these correlations are based on data from all municipalities.

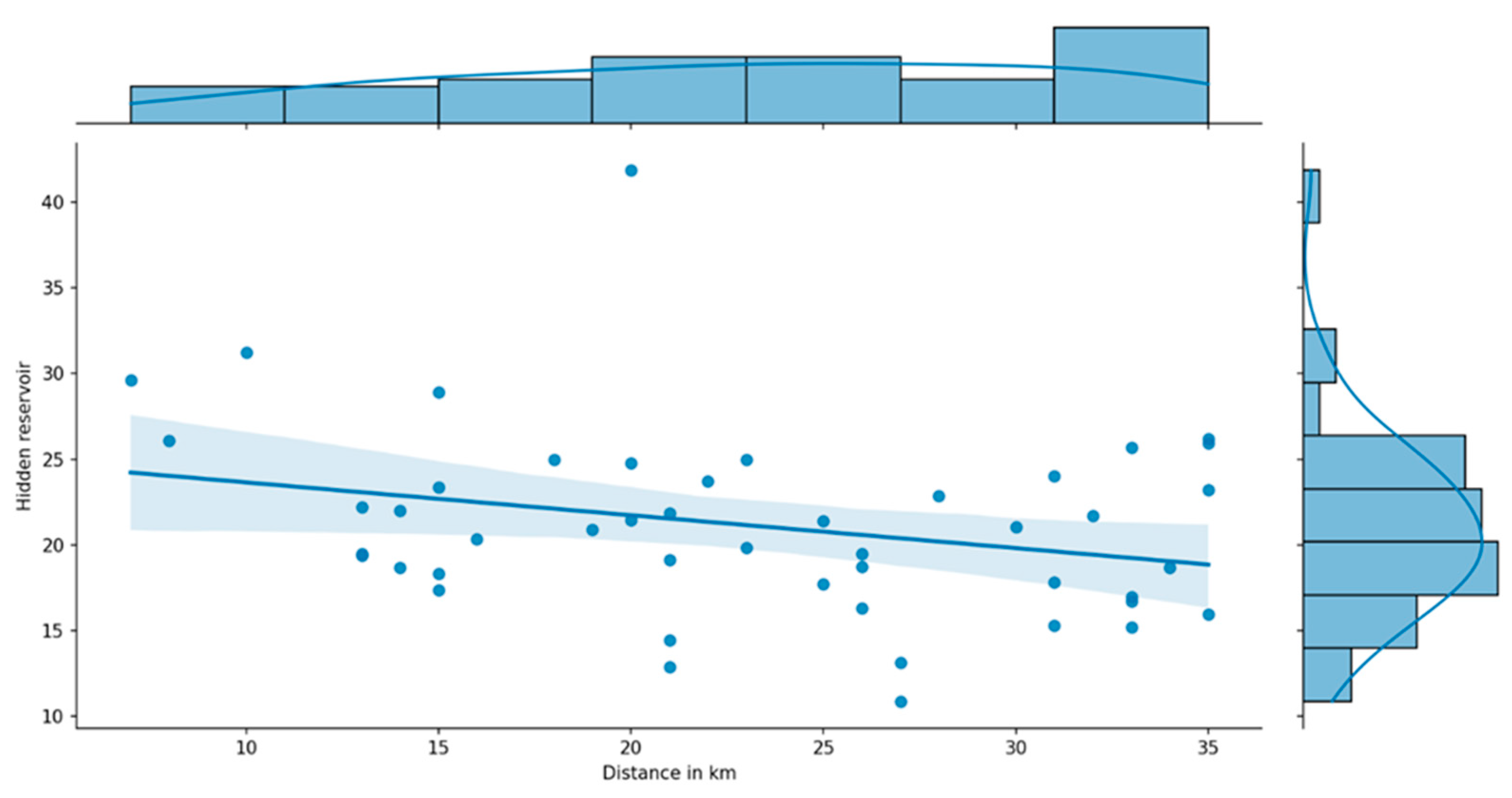

Apart from average personal income, differences in hidden reserves between Tier 1 cities and their surrounding municipalities are also evident. This is reflected in the distance slopes shown in

Table 7. Amsterdam exhibits distance slopes for bachelor nurses that are more than twice as large as those of Rotterdam and The Hague. For healthcare assistants the patterns are different (

Table 7), Amsterdam has the highest hidden reserve with substantially lower hidden reserves in the surrounding municipalities. Rotterdam shows a similar trend, albeit to a lesser degree, while The Hague’s hidden reserve is relatively low, with a slope of almost 0. Considering the small differences in hidden reserves of healthcare assistants (

Table 4) between tiers of municipalities, significant big city effects are unlikely. The largest big city effects are observed for bachelor-trained nurses, whose proportion relative to the total nursing staff is considered a significant contributor to the quality of care. Therefore, stimulating the bachelor-trained hidden reserve is of utmost importance.

Pull factors are attractive options outside the healthcare sector. Especially working conditions, salaries, and career prospects in other economic sectors might lead nurses to decide to work elsewhere. These pull factors will especially operate in metropolitan areas where employment opportunities are high and there are enough alternative jobs. In rural areas with fewer options to work in other healthcare organizations or other economic sectors, pull factors are probably less important.

The fact that the labor market of nurses is local also has consequences for the distinction between rural and urban areas. In the Netherlands, the distinction between rural and non-rural is relative, as it is a densely populated country. Consequently, there are 2nd, 3rd or even 4th tier cities in close proximity to metropolitan areas with economic sectors that are attractive for nurses.

The shortages are substantial in all regions for all professional groups, although the extent of the shortage differs between regions. The shortages may affect the size of the hidden reserve, but as there is a general shortage, we do not expect it to influence the distribution of the hidden reserves. This could be different if there were regions or professional groups with no shortages. Given the local nature of nurse labor markets, there is an even greater imperative to design policies targeting particular regions. For example, giving priority to assigning houses to essential professionals such as nurses in big cities, paying a regional bonus, and extending the nursing school capacity in areas with high shortages. Based on our findings, we also expect that workers in major cities are more sensitive to wage increases than nurses in other areas in the Netherlands. Healthcare organizations in major cities could also attract (former) nurses from surrounding municipalities by offering sufficient financial compensation for longer commuting times.

More generally, activating the hidden reserve could involve strategies such as reducing work pressure and providing greater control over working hours, salary, and autonomy. Many healthcare organizations provide training programs to support former nurses in returning to the profession and renewing their nurse qualification, which may expire if they have been out of practice for a certain period. It is important to note that the hidden reserve of nurses not only includes former nurses working in other sectors but also a significant portion of inactive workers who are currently unemployed [

1]. Therefore, different groups of inactive nurses may require different incentives to re-enter the nursing profession. An important avenue for further research is to examine the effectiveness of different interventions in stimulating inactive nurses to re-enter the profession.

Although all these measures to mitigate nurse shortages could be considered, evidence of their impact is lacking not only on the reduction in nurse shortages but also on the externalities. For example, giving priority to nurses when assigning affordable housing does not improve the push factors, but only reduces the pull of other sectors. As other sectors may also have problems with shortages of staff, this priority policy goes at the expense of these other industries.

Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the Netherlands about the size and composition of the hidden reserve of nurses analyzed from a spatial perspective. In general, the literature about hidden reserves is limited. However, registry data make it possible to analyze the regional differences in the hidden reserve. This is possibly also the case in other countries, and we suggest that more research should be conducted on the spatial aspects of the hidden reserves.

Although we think that our spatial analysis of the hidden reserve provides useful evidence, not all important regional aspects are captured. For instance, the Netherlands is surrounded by a lengthy border with Germany and Belgium. In some areas, Belgian nurses work in Dutch healthcare. In other areas, Dutch nurses work in German healthcare. The geographic distribution of the nurse workforce might be path-dependent and influenced by historical developments. For example, in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, austerity policies within the public sector, including healthcare, restricted the inflow of nurses in nursing schools and health institutions. The impact of these measures may be long-lasting. As nurse education takes a few years, recovery from a temporary drop takes at least this time. Moreover, due to the deliberately caused shortage of nurses, push factors may have become stronger. The effect of these push factors also depends on the role of the municipalities. Our analyses are conducted at the level of municipalities. In urban geography, see, e.g., [

19], these distinctions are often used to distinguish cities not only on the basis of their population size but also to specify their function in the region. Depending on the functions of the city, the regions may vary. A municipality is not the same as a city, but it may cover a region with numerous villages and small towns and be part of an agglomeration. For privacy reasons, we were restricted from performing our analyses at the municipality level and could not perform analyses at the village or town quarter level.

Another limitation of our study is that bachelor-trained nurses who obtained their last degree/diploma before 2000 are not included in this study. Other categories of nurses were excluded if they finished their nursing training before 2004. The number of trained nurses included in the analyses is high enough to be representative of the pattern of spatial distribution, but not of the absolute number. However, we do not know if older nurses (who graduated before 2000) have other mobility or commuting patterns.

Because we did not observe the actual occupation of trained nurses, we categorized all those employed within healthcare as actively contributing to the nursing field. Consequently, our study underestimates the true magnitude of the hidden reserve, as some individuals may hold positions in healthcare management or other related fields. This limitation notwithstanding, nurses engaged in health-related roles both within and beyond traditional healthcare settings play a vital role in shaping the quality and advancement of nursing practice. We recommend expanding nurse registries to encompass roles beyond the confines of the healthcare sector.