Strategies Used by Nurses to Maintain Person–Family Communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

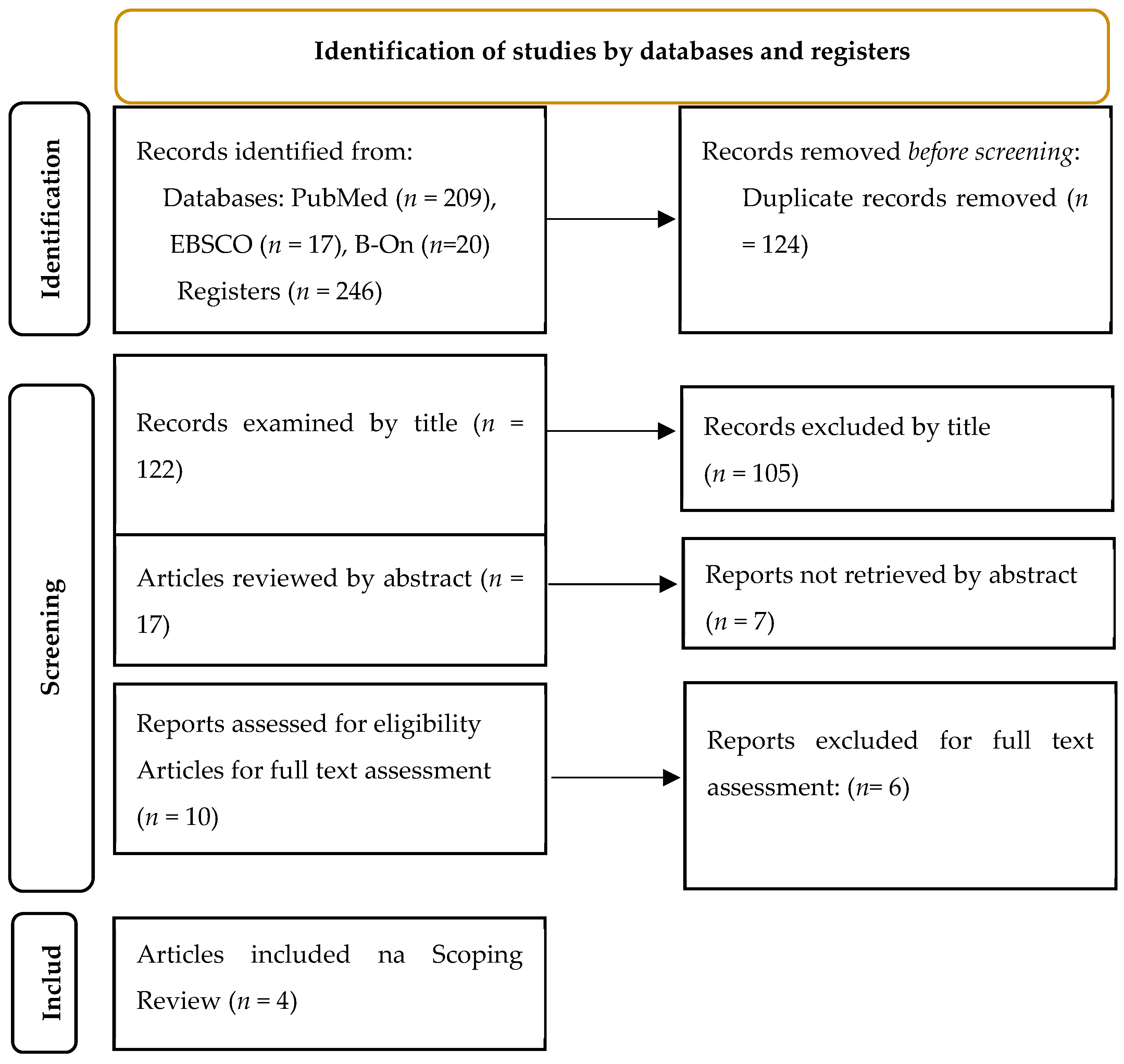

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Direção-Geral da Saúde. Orientação n o 038/2020 de 17/12/2020 2/5. Available online: https://www.hospitaldeguimaraes.min-saude.pt/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2021/03/orientacao-38_2020_dgs.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2023).

- Hollander, J.E.; Carr, B.G. Virtually Perfect? Telemedicine for COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, L.; Yu, L.; Casey, J.; Cook, A.; Metaxa, V.; Pattison, N.; Rafferty, A.M.; Ramsay, P.; Saha, S.; Xyrichis, A.; et al. Communication and virtual visiting for families of patients in intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK national survey. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 1685–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, S.H.; Imanipour, M.; Emamzadeh Ghasemi, H.S.; Razaghi, Z. Effect of Programmed Family Presence in Coronary Care Units on Patients’ and Families’ Anxiety. J. Caring Sci. 2020, 9, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Truong, M.; Watterson, J.R.; Burrell, A.; Wong, P. The impact of the intensive care unit family liaison nurse role on communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study of healthcare professionals’ perspectives. Aust. Crit. Care 2023, 36, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krewulak, K.D.; Jaworska, N.; Spence, K.L.; Mizen, S.J.; Kupsch, S.; Stelfox, H.T.; Parsons Leigh, J.; Fiest, K. Impact of Restricted Visitation Policies during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Communication between Critically Ill Patients, Families, and Clinicians: A Qualitative Interview Study. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2022, 19, 1169–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maaskant, J.M.; Jongerden, I.P.; Bik, J.; Joosten, M.; Musters, S.; Storm-Versloot, M.N.; Wielenga, J.; Eskes, A.; FAM-Corona Group. Strict isolation requires a different approach to the family of hospitalised patients with COVID-19: A rapid qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021, 117, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isidori, V.; Diamanti, F.; Gios, L.; Malfatti, G.; Perini, F.; Nicolini, A.; Longhini, J.; Forti, S.; Fraschini, F.; Bizzarri, G. Digital Technologies and the Role of Health Care Professionals: Scoping Review Exploring Nurses’ Skills in the Digital Era and in the Light of the COVID-19 Pandemic. JMIR Nurs. 2022, 5, e37631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, L.; Mizen, S.; Moss, S.; Brundin-Mather, R.; de Grood, C.; Honarmand, K.; Sumesh, S.; Sangeeta Mehta, S. A qualitative descriptive study of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on staff in a Canadian intensive care unit. Can. J. Anesth. J. Can. 2023, 70, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raftery, C.; Lewis, E.; Cardona, M. The Crucial Role of Nurses and Social Workers in Initiating End-of-Life Communication to Reduce Overtreatment in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Gerontology 2020, 66, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellaneda-Martínez, S.; Jiménez-Mayoral, A.; Humada-Calderón, P.; Redondo-Pérez, N.; del Río-García, I.; Martín-Santos, A.; Maté-Espeso, A.; Fernández-Castro, M. Gestión de la comunicación de los pacientes hospitalizados, aislados con sus familias por la COVID-19. J. Healthc. Qual. Res. 2021, 36, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellaneda-Martínez, S.; Barrios-Díez, E.; Rodríguez-Alcázar, F.; Redondo-Pérez, N.; del Río-García, I.; Martín-Gil, B. Sistema de Alerta Temprana Covid-19 en la historia electrónica de pacientes hospitalizados. Ene 2020, 14, e14312. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1988-348X2020000300012&lng=pt (accessed on 15 May 2023). [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, A.E.; Chessare, C.M.; Coffin, R.K.; Needham, D.M. A brief intervention for preparing ICU families to be proxies: A phase I study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, 0185483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.A.S.; O’Brien, B.F.; Fryday, A.T.; Robinson, E.C.; Hales, M.J.L.; Karipidis, S.; Chadwick, A.; Fleming, K.; Davey-Quinn, A. Developing an Innovative System of Open and Flexible, Patient-Family-Centered, Virtual Visiting in ICU during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Collaboration of Staff, Patients, Families, and Technology Companies. J. Intensive Care Med. 2021, 36, 1130–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xyrichis, A.; Pattison, N.; Ramsay, P.; Saha, S.; Cook, A.; Metaxa, V.; Meyer, J.; Rose, L. Virtual visiting in intensive care during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study with ICU clinicians and non-ICU family team liaison members. BMJ Open 2022, 12, 055679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dainty, K.N.; Seaton, M.B.; Molloy, S.; Robinson, S.; Haberman, S. “I don’t know how we would have coped without it.” Understanding the Importance of a Virtual Hospital Visiting Program during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Patient Exp. 2023, 10, 23743735231155808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Patient and Family-Centered Care. “Facts and Figures” about Family Presence and Participation. 2021. Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Digby, R.; Manias, E.; Haines, K.J.; Orosz, J.; Ihle, J.; Bucknall, T.K. Family experiences and perceptions of intensive care unit care and communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. Crit. Care. 2023, 36, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nº | Author(s) Year/Country | Title | Design | Aim | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Avellaneda-Martínez, et al. 2020, Espain [12] | Management of communication between inpatients isolated due to COVID-19 and their families | Qualitative with action research methodology | Describe the process designed to facilitate communication between patients hospitalized and isolated due to COVID-19 with their families, within the hospital’s quality and humanization plan. | The nursing team, in collaboration with the nursing management, proposed the creation of a group of managers to carry out communication between the hospitalized person and the family. Draft and share consensus statements to enable the healthcare team to provide, via telephone or video calls, an optimal level of communication with patients’ families in circumstances of total isolation. Communication aims to inform the patient’s clinical status and respond to the expectations of families. |

| 2 | Rose, L., Yu, L., Casey, J., Cook, A., Metaxa, V., Pattison, N., Rafferty, A.M., Ramsay, P., Saha, S., Xyrichis, A., Meyer, J., UK [9] | Communication and Virtual Visiting for Families of Patients in Intensive Care during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A UK National Survey | Multicêntric Study | Understand how communication between families, patients, and the ICU team was possible during the pandemic. Understand the strategies used to facilitate virtual visits and the benefits and barriers associated with this methodology. | Videoconferencing technology, and the challenges associated with family members’ ability to use videoconferencing technology or access a device. The most used platforms were the personalized version of the virtual visit platform, TouchAway, developed by the LifeLines team (43, 41%), followed by Skype (27, 25%), and FaceTime (24, 23%). All hospitals started the family visit to the patient in a virtual format. Commonly reported benefits of virtual visits were a reduction of patients’ psychological distress (78%), improved staff morale (68%), and reorientation of patients with delirium (47%). |

| 3 | Chen, R.T., Truong, M., Watterson, J.R., Burrell, A., and Wong, P. 2023, Australia [13] | The impact of the intensive care unit family liaison nurse role on communication during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative descriptive study of healthcare professionals | A qualitative descriptive study | This study aimed to explore the impact of the role of the ICU Family Liaison Nurse on communicating with patients and their families during the COVID-19 pandemic, from the perspective of ICU healthcare professionals. | Participants felt that telehealth was a great help and played an important role in facilitating communication between patients and their families. It was relatively easy and less time-consuming to organize a telehealth meeting than an in-person meeting. Telehealth allowed families to see the faces of their loved ones and what is happening in the ICU, which was especially important during the closure. They again reported that communication was more regular and organized during the pandemic with the use of telehealth. A reservation system was implemented to schedule calls and meetings with family members, healthcare providers, and interpreters. Family liaison nurses were created to facilitate communication between the hospitalized patient and the family. |

| 4 | Maaskant, I.P. Jongerde, J. Bik, M. Joosten, S. Musters, M.N. Storm-Versloot, J. Wielenga, A.M. Eskes, on behalf of the FAM-Corona Group 2021, the Netherlands [7] | Strict isolation requires a different approach to the family of hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A rapid qualitative study | Qualitative study, using a retrospective review of patient records and semi-structured focus group interviews. | Investigate how family involvement had occurred, and explore nurses’ experiences with family involvement during the COVID-19 outbreak; formulate recommendations for family involvement. | The contact between the family and the health professionals was done mainly through video or telephone calls. An important precondition for contact between patients, their families, and/or healthcare professionals was the availability of telephones and the ability to use them. Most units had unstructured communication with the family, often depending on individual family or bedside nurse actions. In the focus groups, nurses explained that contact with families was much less than before the COVID-19 outbreak. the restricted visitation policy resulted in the absence of family, and (informal) communication stopped. |

| Communication Strategies | Creation of a group of managers to carry out the communication: 1; 4. |

| Draft and share consensus statements to enable the healthcare team to provide an optimal level of communication with patients’ families in circumstances of total isolation: 1. | |

| Phone calls to try to meet the expectations of families: 1; 2; 3; 4. | |

| Visita virtual—Os hospitais iniciaram a visita da família ao doente em formato virtual: 1; 2; 3; 4. | |

| Organizar visitas de telehealth foi uma grande ajuda e desempenhou um papel importante na facilitação da comunicação entre doentes e familiares: 3. | |

| Implementing a reservation system to schedule calls and meetings with family members, healthcare providers, and interpreters: 3. | |

| Family liaison nurses were created to facilitate communication between the hospitalized patient and the family: 3. | |

| Phone calls with unstructured communication with the family, often depending on individual actions by the family or the nurse responsible for the patient: 1; 2; 3; 4. | |

| Communication Tools | O telefone ou videochamadas, foram as tecnologias para manter a comunicação com os familiares dos doentes em circunstâncias de isolamento total 1; 4. |

| Videoconferencing technology or accessing a device. The most used platforms for the virtual tour were TouchAway, developed by the LifeLines team, followed by Skype and FaceTime: 2. | |

| Telehealth was a great help and played an important role in facilitating communication between patients and their families: 3. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teixeira, D.; Costa, S.; Branco, A.; Silva, A.; Polo, P.; Nogueira, M.J. Strategies Used by Nurses to Maintain Person–Family Communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Nurs. Rep. 2023, 13, 1138-1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030098

Teixeira D, Costa S, Branco A, Silva A, Polo P, Nogueira MJ. Strategies Used by Nurses to Maintain Person–Family Communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports. 2023; 13(3):1138-1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030098

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeixeira, Delfina, Sandra Costa, Ana Branco, Ana Silva, Pablo Polo, and Maria José Nogueira. 2023. "Strategies Used by Nurses to Maintain Person–Family Communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review" Nursing Reports 13, no. 3: 1138-1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030098

APA StyleTeixeira, D., Costa, S., Branco, A., Silva, A., Polo, P., & Nogueira, M. J. (2023). Strategies Used by Nurses to Maintain Person–Family Communication during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review. Nursing Reports, 13(3), 1138-1147. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep13030098