Epidemiological and Clinical Profile of Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemia in Duhok, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Research Design, Population, Setting, and Sampling

2.2. Study Measures

2.3. Vaccination Procedures

2.4. Costs of the Services at Zheen Center

2.5. Hemoglobinopathies Diagnosis

2.6. Statistical Analyses

2.7. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

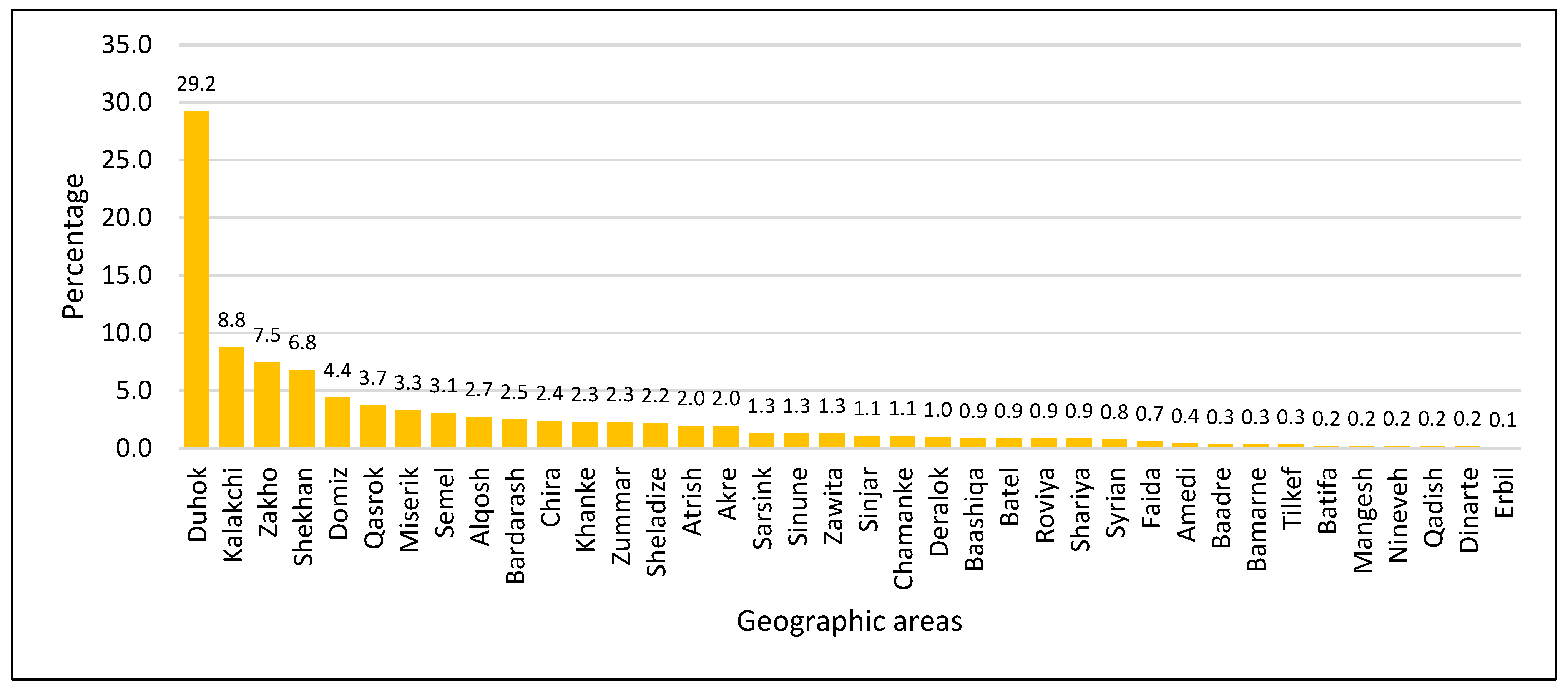

3.1. General, Clinical, and Geographic Characteristics of Thalassemia Patients in Duhok

3.2. Associations Between Thalassemia Diagnoses, Parental Consanguinity, and Residency in Duhok Governorate

3.3. Predictors of Thalassemia in Kurdistan Region

3.4. Vaccination History Among Thalassemia Patients in Duhok Governorate

4. Discussion

4.1. Epidemiological Insights and Socioeconomic Implications of Thalassemia in Duhok

4.2. Geodemographic Patterns and Sociocultural Determinants of Thalassemia in Duhok

4.3. Clinical and Treatment Outcomes of Thalassemia in Duhok

4.4. Vaccination Coverage and Preventive Care in Duhok

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.6. Implications for Policy and Practice and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tuo, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, S.; Jin, J.; He, Z. Global, regional, and national burden of thalassemia, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Eclinicalmedicine 2024, 72, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattamis, A.; Kwiatkowski, J.L.; Aydinok, Y. Thalassaemia. Lancet 2022, 399, 2310–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherall, D.; Stamatoyannopoulos, G.; Neinhuis, A.; Majerus, P.; Varmus, H. The Thalassemias in the Molecular Basis of Blood Diseases; Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Taher, A.T.; Musallam, K.M.; Cappellini, M.D. β-Thalassemias. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, M.; Flight, P.A.; Paramore, L.C.; Tian, L.; Milenković, D.; Sheth, S. Systematic literature review of the burden of disease and treatment for transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia. Clin. Ther. 2020, 42, 322–337.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.M.; Poggi, M.; Russo, R.; Giusti, A.; Forni, G.L. Management of the aging beta-thalassemia transfusion-dependent population–The Italian experience. Blood Rev. 2019, 38, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AB, A.S.; Nour El Huda, A.; Safurah, J. A systematic review on thalassaemia screening and birth reduction initiatives: Cost to success. Med. J. Malays. 2024, 79, 348–359. [Google Scholar]

- Shafie, A.A.; Wong, J.H.Y.; Ibrahim, H.M.; Mohammed, N.S.; Chhabra, I.K. Economic burden in the management of transfusion-dependent thalassaemia patients in Malaysia from a societal perspective. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musallam, K.M.; Lombard, L.; Kistler, K.D.; Arregui, M.; Gilroy, K.S.; Chamberlain, C.; Zagadailov, E.; Ruiz, K.; Taher, A.T. Epidemiology of clinically significant forms of alpha-and beta-thalassemia: A global map of evidence and gaps. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1436–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattamis, A.; Forni, G.L.; Aydinok, Y.; Viprakasit, V. Changing patterns in the epidemiology of β-thalassemia. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020, 105, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gazali, L.; Hamamy, H.; Al-Arrayad, S. Genetic disorders in the Arab world. BMJ 2006, 333, 831–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiry, P.; Al-Attar, S.; Hegele, R. Understanding beta-thalassemia with focus on the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East. Open Hematol. J. 2008, 2, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, B.; Zaher, A. Consanguineous marriages in the middle east: Nature versus nurture. Open Complement. Med. J. 2013, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Old, J. Prevention and Diagnosis of Haemoglobinpathies; Thalassemia International Federation TIF Publication: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Colah, R.; Gorakshakar, A.; Nadkarni, A. Global burden, distribution and prevention of β-thalassemias and hemoglobin E disorders. Expert Rev. Hematol. 2010, 3, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Rhee, T.M.; Jeon, K.; Cho, Y.; Lee, S.W.; Han, K.D.; Seong, M.W.; Park, S.S.; Lee, Y.K. Epidemiologic Trends of Thalassemia, 2006-2018: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, K.A.; Baldawi, K.H.; Lami, F.H. Prevalence, incidence, trend, and complications of thalassemia in Iraq. Hemoglobin 2017, 41, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Jamalian, N.; Yarmohammadi, H.; Askarnejad, A.; Afrasiabi, A.; Hashemi, A. Premarital screening for β-thalassaemia in Southern Iran: Options for improving the programme. J. Med. Screen. 2007, 14, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamy, H.A.; Al-Allawi, N.A. Epidemiological profile of common haemoglobinopathies in Arab countries. J. Community Genet. 2013, 4, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, K.; Huang, G.; Su, L.; He, Y. The prevalence of thalassemia in mainland China: Evidence from epidemiological surveys. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, L.P.W.; Chong, E.T.J.; Lee, P.C. Prevalence of Alpha(α)-Thalassemia in Southeast Asia (2010–2020): A Meta-Analysis Involving 83,674 Subjects. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Martinez, P.; Angastiniotis, M.; Eleftheriou, A.; Gulbis, B.; Mañú Pereira Mdel, M.; Petrova-Benedict, R.; Corrons, J.L. Haemoglobinopathies in Europe: Health & migration policy perspectives. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.K. New trend in the epidemiology of thalassaemia. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2017, 39, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Dom, T.N.; Ayob, R.; Abd Muttalib, K.; Aljunid, S.M. National economic burden associated with management of periodontitis in Malaysia. Int. J. Dent. 2016, 2016, 1891074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafta, R.; Sadiq, R.; Muhammed, Z. Burden of thalassemia in Iraq. Public Health Open Access (PHOA) 2023, 7, 000242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Badawy, S.M. Health-related quality of life with standard and curative therapies in thalassemia: A narrative literature review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1532, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, S.; Hamad, B.; Hamad, H.; Qader, M.; Ali, E.; Muhammed, R.; Shekha, M. Estimation of the prevalence of Hemoglobinopathies in Erbil governorate, Kurdistan region of Iraq. Iraqi J. Hematol. 2022, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Allawi, N.; Al Allawi, S.; Jalal, S.D. Genetic epidemiology of hemoglobinopathies among Iraqi Kurds. J. Community Genet. 2021, 12, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, R.Z.; Hassan, M.K.; Al-Salait, S.K. Microcytosis in children and adolescents with the sickle cell trait in Basra, Iraq. Blood Res. 2019, 54, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebari, S.A. Prevalence of Hemoglobinopathies Among the Kurdish Population in Zakho City, Kurdistan Region, Iraq. Cureus 2025, 17, e78862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husna, N.; Arif, A.; Putri, C.; Leonard, E.; Satuti, N. Prevalence and Distribution of Thalassemia Trait Screening. J. Med. Sci. 2017, 49, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Allawi, N.; Jalal, S.; Ahmed, N.; Faraj, A.; Shalli, A.; Hamamy, H. The first five years of a preventive programme for haemoglobinopathies in Northeastern Iraq. J. Med. Screen. 2013, 20, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Eastern Mediterranean. Republic of Iraq: Iraq Family Health Survey 2006/7. 3 May 2007. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/iraq/iraq-family-health-survey-20067 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Inati, A.; Zeineh, N.; Isma’eel, H.; Koussa, S.; Gharzuddine, W.; Taher, A. Beta-thalassemia: The Lebanese experience. Clin. Lab. Haematol. 2006, 28, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, L.; Sorrentino, F.; Caprari, P.; Taliani, G.; Massimi, S.; Risoluti, R.; Materazzi, S. HCV Infection in Thalassemia Syndromes and Hemoglobinopathies: New Perspectives. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzziello, A.; Loquercio, G.; Sabatino, R.; Balaban, D.V.; Ullah Khan, N.; Piccirillo, M.; Rodrigo, L.; di Capua, L.; Guzzo, A.; Labonia, F.; et al. Prevalence of Hepatitis C virus genotypes in nine selected European countries: A systematic review. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 33, e22876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cario, H.; Stahnke, K.; Sander, S.; Kohne, E. Epidemiological situation and treatment of patients with thalassemia major in Germany: Results of the German multicenter beta-thalassemia study. Ann. Hematol. 2000, 79, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajab, A.G.; Patton, M.A.; Modell, B. Study of hemoglobinopathies in Oman through a national register. Saudi Med. J. 2000, 21, 1168–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Angelucci, E. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in thalassemia. Haematologica 1994, 79, 353–355. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, F.T.; Porter, J.B.; Sadasivam, N.; Kaya, B.; Moon, J.C.; Velangi, M.; Ako, E.; Pancham, S. Guidelines for the monitoring and management of iron overload in patients with haemoglobinopathies and rare anaemias. Br. J. Haematol. 2022, 196, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayani, F.A.; Kwiatkowski, J.L. Increasing prevalence of thalassemia in America: Implications for primary care. Ann. Med. 2015, 47, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algeri, M.; Lodi, M.; Locatelli, F. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in thalassemia. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. 2023, 37, 413–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolghasemi, H.; Amid, A.; Zeinali, S.; Radfar, M.H.; Eshghi, P.; Rahiminejad, M.S.; Ehsani, M.A.; Najmabadi, H.; Akbari, M.T.; Afrasiabi, A.; et al. Thalassemia in Iran: Epidemiology, Prevention, and Management. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2007, 29, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Abbasi, S.-U.-R.; Manzoor, M. Socio-religious Prognosticators of Psychosocial Burden of Beta Thalassemia Major. J. Relig. Health 2020, 59, 2866–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nietert, P.; Silverstein, M.; Abboud, M. Sickle Cell Anaemia: Epidemiology and Cost of Illness. PharmacoEconomics 2002, 20, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riaz, M.; Abbas, M.; Rasool, G.; Baig, I.S.; Mahmood, Z.; Munir, N.; Mahmood Tahir, I.; Ali Shah, S.M.; Akram, M. Prevalence of transfusion-transmitted infections in multiple blood transfusion-dependent thalassemic patients in Asia: A systemic review. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2022, 36, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan: Monitoring, Evaluation and Accountability; Secretariat Annual Report 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Child Vaccines Towards Sustainable Development Goals in Iraq. 2023. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/iraq/stories/child-vaccines-towards-sustainable-development-goals-iraq?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 April 2025).

| General and Clinical Characteristics (n = 910) | Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | ||

| Age (0–57 years) | Neonates (0–28 days) | 4 | 0.44 |

| Infant (29 days-1 year) | 353 | 38.79 | |

| Preschool (2–5 years) | 253 | 27.80 | |

| School Children (6–11 years) | 150 | 16.48 | |

| Adolescent (12–17 years) | 63 | 6.92 | |

| Adult (≥18 years) | 87 | 9.56 | |

| Gender | Male | 425 | 46.70 |

| Female | 485 | 53.30 | |

| Parent Consanguinity | No | 378 | 41.54 |

| Yes | 532 | 58.46 | |

| HCV | Negative | 802 | 88.13 |

| Positive | 108 | 11.87 | |

| Bone marrow transplantation | No | 829 | 91.10 |

| Yes | 81 | 8.90 | |

| Splenectomy | No | 636 | 69.89 |

| Yes | 274 | 30.11 | |

| Blood group | O+ | 330 | 36.26 |

| A+ | 282 | 30.99 | |

| B+ | 168 | 18.46 | |

| AB+ | 67 | 7.36 | |

| A− | 24 | 2.64 | |

| O− | 21 | 2.31 | |

| B− | 14 | 1.54 | |

| AB− | 4 | 0.44 | |

| Deferasirox (Exjade®) * | No | 520 | 57.14 |

| Stopped | 75 | 8.24 | |

| Yes | 315 | 34.62 | |

| Deferoxamine mesylate (Desferal ®) ** | No | 857 | 94.18 |

| Yes | 53 | 5.82 | |

| Hydroxyurea | No | 627 | 68.90 |

| Stopped | 40 | 4.40 | |

| Yes | 243 | 26.70 | |

| Marital status | Child | 109 | 11.98 |

| Single | 704 | 77.36 | |

| Married | 97 | 10.66 | |

| Education | Child | 109 | 11.98 |

| Illiterate | 54 | 5.93 | |

| Read and write | 61 | 6.70 | |

| Primary | 343 | 37.69 | |

| Secondary | 171 | 18.79 | |

| High school | 97 | 10.66 | |

| Institute | 34 | 3.74 | |

| College | 37 | 4.07 | |

| Master of Science | 4 | 0.44 | |

| Occupation | Student | 523 | 57.47 |

| Housewife | 131 | 14.40 | |

| Unemployed | 110 | 12.09 | |

| Child | 109 | 11.98 | |

| Employee | 33 | 3.63 | |

| Peshmerga | 4 | 0.44 | |

| No of patients in family | Range: 1–6 | Mean: 1.79 | SD: 0.90 |

| No of patients in family | 1–2 patients | 757 | 83.19 |

| >2 patients | 153 | 16.81 | |

| Drug allergy | No | 877 | 96.37 |

| Yes | 33 | 3.63 | |

| SES | Low | 672 | 73.85 |

| Middle | 233 | 25.60 | |

| High | 5 | 0.55 | |

| Religion | Muslim | 800 | 87.91 |

| Yazidi | 107 | 11.76 | |

| Christian | 3 | 0.33 | |

| Ethnicity | Kurd | 897 | 98.57 |

| Chaldean | 2 | 0.22 | |

| Arab | 10 | 1.10 | |

| Turkman | 1 | 0.11 | |

| Outcomes (n = 910) | No. (%) | Gender | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | Male | Female | p-Value | ||

| Mortality | No | 904 (99.34) | 423 (99.53) | 481 (99.18) | 0.690 |

| Yes | 6 (0.66) | 2 (0.47) | 4 (0.82) | ||

| Disease duration | <1 year | 262 (30.18) | 129 (31.31) | 133 (29.17) | 0.235 |

| 1–2 years | 381 (43.89) | 164 (39.81) | 217 (47.59) | ||

| 3–5 years | 104 (11.98) | 57 (13.83) | 47 (10.31) | ||

| 6–11 years | 55 (6.34) | 28 (6.80) | 27 (5.92) | ||

| 12–18 years | 38 (4.38) | 19 (4.61) | 19 (4.17) | ||

| 19–21 years | 5 (0.58) | 4 (0.97) | 1 (0.22) | ||

| >21 years | 23 (2.65) | 11 (2.67) | 12 (2.63) | ||

| Disease type | Β thalassemia major | 296 (32.53) | 136 (32.00) | 160 (32.99) | 0.907 |

| sickle cell anemia | 225 (24.73) | 113 (26.59) | 112 (23.09) | ||

| sickle cell β thalassemia | 152 (16.70) | 69 (16.24) | 83 (17.11) | ||

| Β-thalassemia intermedia | 136 (14.95) | 57 (13.41) | 79 (16.29) | ||

| Alpha-thalassemia | 47 (5.17) | 22 (5.18) | 25 (5.15) | ||

| Fanconi anemia | 18 (1.98) | 9 (2.12) | 9 (1.86) | ||

| Aplastic anemia | 16 (1.76) | 9 (2.12) | 7 (1.44) | ||

| chronic non-spherocytic H.A | 7 (0.77) | 3 (0.71) | 4 (0.82) | ||

| Hereditary spherocytosis | 6 (0.66) | 3 (0.71) | 3 (0.62) | ||

| sickle cell alpha thalassemia | 4 (0.44) | 3 (0.71) | 1 (0.21) | ||

| pure red cell aplasia | 2 (0.22) | 1 (0.24) | 1 (0.21) | ||

| Hemochromatosis | 1 (0.11) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.21) | ||

| General and Clinical Characteristics (n = 910) | Diagnosis No (%) Percentage by Row | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-Thalassemia (n = 47) | Aplastic Anaemia (n = 16) | Β Thalassemia Major (n = 296) | Β-Thalassemia Intermedia (n = 136) | Fanconi Anemia (n = 18) | Sickle Cell Anemia (n = 225) | Sickle Cell β-Thalassemia (n = 152) | p-Value | |

| Gender | 0.782 | |||||||

| Male | 22 (5.30) | 9 (2.17) | 136 (32.77) | 57 (13.73) | 9 (2.17) | 113 (27.23) | 69 (16.63) | |

| Female | 25 (5.26) | 7 (1.47) | 160 (33.68) | 79 (16.63) | 9 (1.89) | 112 (23.58) | 83 (17.47) | |

| HCV | 0.005 | |||||||

| Negative | 45 (5.74) | 15 (1.91) | 250 (31.89) | 127 (16.20) | 18 (2.30) | 189 (24.11) | 140 (17.86) | |

| Positive | 2 (1.89) | 1 (0.94) | 46 (43.40) | 9 (8.49) | 0 (0.00) | 36 (33.96) | 12 (11.32) | |

| BMT | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 47 (100) | 15 (93.75) | 231 (78.04) | 134 (98.53) | 14 (77.78) | 220 (97.78) | 148 (97.37) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.00) | 1 (6.25) | 65 (21.96) | 2 (1.47) | 4 (22.22) | 5 (2.22) | 4 (2.63) | |

| Splenectomy | <0.001 | |||||||

| No | 45 (7.20) | 16 (2.56) | 181 (28.96) | 88 (14.08) | 18 (2.88) | 185 (29.60) | 92 (14.72) | |

| Yes | 2 (0.75) | 0 (0.00) | 115 (43.40) | 48 (18.11) | 0 (0.00) | 40 (15.09) | 60 (22.64) | |

| Religion | 0.002 | |||||||

| Muslim | 47 (6.02) | 16 (2.05) | 267 (34.19) | 106 (13.57) | 16 (2.05) | 190 (24.33) | 139 (17.80) | |

| Yazidi | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 28 (26.42) | 28 (26.42) | 2 (1.89) | 35 (33.02) | 13 (12.26) | |

| Christian | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (33.33) | 2 (66.67) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Disease age | <0.001 | |||||||

| <1 year | 6 (2.29) | 2 (0.76) | 135 (51.53) | 25 (9.54) | 0 (0.00) | 64 (24.43) | 26 (9.92) | |

| 1–2 years | 17 (4.46) | 4 (1.05) | 99 (25.98) | 59 (15.49) | 8 (2.10) | 102 (26.77) | 81 (21.26) | |

| 3–5 years | 10 (9.62) | 3 (2.88) | 18 (17.31) | 23 (22.12) | 4 (3.85) | 27 (25.96) | 19 (18.27) | |

| 6–11 years | 3 (5.45) | 2 (3.64) | 16 (29.09) | 7 (12.73) | 4 (7.27) | 11 (20.00) | 11 (20.00) | |

| 12–18 years | 7 (18.42) | 3 (7.89) | 6 (15.79) | 5 (13.16) | 1 (2.63) | 8 (21.05) | 8 (21.05) | |

| 19–21 years | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (20.00) | 2 (40.00) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (20.00) | 1 (20.00) | |

| >21 years | 2 (8.70) | 2 (8.70) | 8 (34.78) | 6 (26.09) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (8.70) | 2 (8.70) | |

| Occupation | <0.001 | |||||||

| Child | 2 (1.83) | 1 (0.92) | 46 (42.20) | 16 (14.68) | 4 (3.67) | 22 (20.18) | 16 (14.68) | |

| Employee | 4 (12.12) | 0 (0.00) | 11 (33.33) | 5 (15.15) | 0 (0.00) | 10 (30.30) | 3 (9.09) | |

| Housewife | 12 (9.16) | 0 (0.00) | 27 (20.61) | 20 (15.27) | 0 (0.00) | 42 (32.06) | 28 (21.37) | |

| peshmerga | 2 (50.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (50.00) | 0 (0.00) | |

| Student | 224.21) | 15 (2.87) | 181 (34.61) | 73 (13.96) | 11 (2.10) | 123 (23.52) | 82 (15.68) | |

| Unemployed | 5 (4.55) | 0 (0.00) | 31 (28.18) | 22 (20.00) | 3 (2.73) | 26 (23.64) | 23 (20.91) | |

| Residency (n = 740) | Parent Consanguinity No (%) The Percentages Are by Total | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No (318, 42.97%) | Yes (422, 57.03%) | ||

| Alqosh | 12 (1.62) | 13 (1.76) | 0.020 |

| Bardarash | 12 (1.62) | 11 (1.49) | |

| Chira | 10 (1.35) | 12 (1.62) | |

| Domiz | 12 (1.62) | 28 (3.78) | |

| Duhok | 128 (17.30) | 138 (18.65) | |

| Kalakchi | 31 (4.19) | 49 (6.62) | |

| Khanke | 6 (0.81) | 15 (2.03) | |

| Miserik | 13 (1.76) | 17 (2.30) | |

| Qasrok | 7 (0.95) | 27 (3.65) | |

| Semel | 17 (2.30) | 11 (1.49) | |

| Shekhan | 30 (4.05) | 32 (4.32) | |

| Sheladize | 11 (1.49) | 9 (1.22) | |

| Zakho | 22 (2.97) | 46 (6.22) | |

| Zummar | 7 (0.95) | 14 (1.89) | |

| Factors (n = 907) * | Outcome: Β Thalassemia Major vs. Other Types | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| HCV; Positive/Negative | 1.60 (1.05–2.42) | 0.027 |

| Religion; Muslim/Yazidi | 1.43 (0.92–2.30) | 0.117 |

| SES | 0.146 | |

| Low/Good | 0.32 (0.04–1.97) | |

| Low/Middle | 1.28 (0.92–1.78) | |

| Parent Consanguinity; Yes/No | 1.20 (0.90–1.60) | 0.207 |

| Gender; Male/Female | 0.92 (0.70–1.22) | 0.575 |

| Factors (n = 907) * | Outcome: sickle cell anemia vs. other types | p-value |

| Parent Consanguinity; Yes/No | 2.71 (1.94–3.83) | <0.001 |

| Religion; Yazidi/Muslim | 1.65 (1.05–2.58) | 0.032 |

| HCV; Positive/Negative | 1.57 (1.00–2.44) | 0.052 |

| SES | ||

| Low/Good | 1.69 (0.24–33.67) | 0.277 |

| Low/Middle | 1.34 (0.93–1.96) | |

| Gender; Male/Female | 1.17 (0.86–1.60) | 0.322 |

| Factors (n = 907) * | Outcome: sickle cell β thalassemia vs. other types | p-value |

| Parent Consanguinity; No/Yes | 3.23 (2.25–4.70) | <0.001 |

| HCV; Positive/Negative | 0.57 (0.29–1.05) | 0.072 |

| Religion; Muslim/Yazidi | 1.68 (0.93–3.26) | 0.088 |

| SES | ||

| Low/Good | 677,622.6 (0.35-.) | 0.321 |

| Low/Middle | 1.20 (0.80–1.84) | |

| Gender; Male/Female | 1.01 (0.71–1.46) | 0.936 |

| Factors (n = 907) * | Outcome: Β-thalassemia intermedia vs, other types | p-value |

| Religion; Yazidi/Muslim | 2.34 (1.42–3.75) | 0.001 |

| HCV; Positive/Negative | 0.53 (0.24–1.03) | 0.060 |

| Parent Consanguinity; Yes/No | 0.76 (0.53–1.11) | 0.160 |

| Gender; Male/Female | 0.83 (0.57–1.20) | 0.323 |

| SES: | ||

| Low/Good | 0.70 (0.10–14.00) | 0.422 |

| Low/Middle | 0.76 (0.51–1.16) |

| Vaccines (n = 1855) | Vaccination History | |

|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |

| Hepatitis B (1st Dose) | 1130 (60.92) | 725 (39.08) |

| Hepatitis B (2nd Dose) | 1192 (64.26) | 663 (35.74) |

| Hepatitis B (3rd Dose) | 1302 (70.19) | 553 (29.81) |

| Meningococcal vaccine (1st Dose) | 1003 (54.07) | 852 (45.93) |

| Meningococcal vaccine (2nd Dose) | 1794 (96.71) | 61 (3.29) |

| Meningococcal vaccine (3rd Dose) | 1846 (99.51) | 9 (0.49) |

| Meningococcal vaccine (B1) | 1855 (100) | 0 (0.0) |

| Meningococcal vaccine (B2) | 1849 (99.68) | 6 (0.32) |

| Pneumococcal vaccines. (1st Dose) | 913 (49.22) | 942 (50.78) |

| Pneumococcal vaccines. (2nd Dose) | 1717 (92.56) | 138 (7.44) |

| Pneumococcal vaccines. (3rd Dose) | 1850 (99.73) | 5 (0.27) |

| Pneumococcal vaccines. (4th Dose) | 1854 (99.95) | 1 (0.05) |

| Influenza vaccine | 969 (52.24) | 886 (47.76) |

| MMR (1st Dose) | 1844 (99.41) | 11 (0.59) |

| MMR (2nd Dose) | 1847 (99.57) | 8 (0.43) |

| OPV (1st Dose) | 1423 (76.71) | 432 (23.29) |

| OPV (2nd Dose) | 1815 (97.84) | 40 (2.16) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaman, B.A.; Mustafa, Z.R.; Mohamed, D.A.; Aswad, H.A.; Abdulah, D.M. Epidemiological and Clinical Profile of Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemia in Duhok, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Retrospective Study. Thalass. Rep. 2025, 15, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040012

Zaman BA, Mustafa ZR, Mohamed DA, Aswad HA, Abdulah DM. Epidemiological and Clinical Profile of Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemia in Duhok, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Retrospective Study. Thalassemia Reports. 2025; 15(4):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040012

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaman, Burhan Abdullah, Zuhair Rushdi Mustafa, Delshad Abdulah Mohamed, Hasan Abdullah Aswad, and Deldar Morad Abdulah. 2025. "Epidemiological and Clinical Profile of Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemia in Duhok, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Retrospective Study" Thalassemia Reports 15, no. 4: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040012

APA StyleZaman, B. A., Mustafa, Z. R., Mohamed, D. A., Aswad, H. A., & Abdulah, D. M. (2025). Epidemiological and Clinical Profile of Hemoglobinopathies and Thalassemia in Duhok, Kurdistan Region of Iraq: A Retrospective Study. Thalassemia Reports, 15(4), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040012