Temporal Changes in Quality of Life and Psychological Burden of Patients with Thalassemia: A Comparative Data Analysis from 2018 to 2025

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Sample and Participants

2.2. Research Tools

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waheed, F. Thalassaemia Prevention in Maldives: Effectiveness of Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Prevention Interventions. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pangalou, E.; Meletis, G. Honor Tome of Professor Meletis; Archives of Hellenic Medicine: Lefkosia, Cyprus, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, S.; Jin, J.; He, Z. Global, regional, and national burden of thalassemia, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. eClinicalMedicine 2024, 72, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonizakis, P.; Roy, N.; Papatsouma, I.; Mainou, M.; Christodoulou, I.; Pantelidou, D.; Kokkota, S.; Diamantidis, M.; Kourakli, A.; Lazaris, V.; et al. A Cross-Sectional, Multicentric, Disease-Specific, Health-Related Quality of Life Study in Greek Transfusion Dependent Thalassemia Patients. Healthcare 2024, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Taher, A.T.; Piga, A.; Shah, F.; Voskaridou, E.; Viprakasit, V.; Porter, J.B.; Hermine, O.; Neufeld, E.J.; Thompson, A.A.; et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with β-thalassemia: Data from the phase 3 BELIEVE trial of luspatercept. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 111, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutelekos, I.; Haliasos, N. Thalassaemia. Perioper. Nurs. 2013, 2, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Eleftheriou, A.; Cannon, L.; Angastiniotis, M. Thalassaemia Prior and Consequent to COVID-19 Pandemic. The Perspective of Thalassaemia International Federation (TIF). Thalass. Rep. 2020, 10, 9138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmakis, D.; Giakoumis, A.; Cannon, L.; Angastiniotis, M.; Eleftheriou, A. COVID-19 and thalassaemia: A position statement of the Thalassaemia International Federation. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020, 105, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rikos, N.; Giannadaki, G.; Spontidaki, A.; Tzagkaraki, M.; Linardakis, M. Health status, anxiety, depression, and quality of life of patients with thalassemia. J. Public Health 2021, 29, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.F. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Occup. Med. 2014, 64, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontodimopoulos, N.; Pappa, E.; Niakas, D.; Yfantopoulos, J.; Dimitrakaki, C.; Tountas, Y. Validity of the EuroQoL (EQ-5D) instrument in a Greek general population. Value Health 2008, 11, 1162–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michopoulos, I.; Douzenis, A.; Kalkavoura, C.; Christodoulou, C.; Michalopoulou, P.; Kalemi, G.; Fineti, K.; Patapis, P.; Protopapas, K.; Lykouras, L. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): Validation in a Greek general hospital sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2008, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, A.; Ikonomakis, E.; Kontodimopoulos, N.; Frydas, A.; Niakas, D. Assessment of health-related quality of life for diabetic patients type 2. Arch. Hell. Med. 2007, 24 (Suppl. S1), 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rushaidi, A.; Al-Hinai, S.; Al-Sumri, H. Health-related Quality of Life of Omani Adult Patients with β-Thalassemia Major at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital. Oman Med. J. 2024, 39, e613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drahos, J.; Boateng-Kuffour, A.; Calvert, M.; Levine, L.; Dongha, N.; Li, N.; Pakbaz, Z.; Shah, F.; Martin, A.P. Health-Related Quality-of-Life Impacts Associated with Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassemia in the USA and UK: A Qualitative Assessment. Patient 2024, 17, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoth, R.L.; Gupta, S.; Perkowski, K.; Costantino, H.; Inyart, B.; Ashka, L.; Clapp, K. Understanding the Association between Red Blood Cell Transfusion Utilization and Humanistic and Economic Burden in Patients with β-Thalassemia from the Patients’ Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohlbry, P.; Al-Karmi, B.; Yamashita, R. Quality-of-life of patients living with thalassaemia in the West Bank and Gaza. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2023, 29, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poormansouri, S.; Ahmadi, M.; Shariati, A.A.; Keikhaei, B. Quality of life, depression, anxiety and stress in over-18-year-old patients with beta-Thalassemia major. J. Iran. Blood Transfus. 2016, 13, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Luo, B.; Ming, J.; Zhang, X.; Weng, J.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Y. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among children with Transfusion-dependent β-thalassaemia: A cross-sectional study in Guangxi Province. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2024, 22, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedone, F.; Lamendola, P.; Lopatriello, S.; Cafiero, D.; Piovani, D.; Forni, G.L. Quality of Life and Burden of Disease in Italian Patients with Transfusion-Dependent Beta-Thalassemia. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foong, W.C.; Chean, K.Y.; Rahim, F.F.; Goh, A.S.; Yeoh, S.L.; Yeoh, A.A.C. Quality of life and challenges experienced by the surviving adults with transfusion dependent thalassaemia in Malaysia: A cross sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yengil, E.; Acipayam, C.; Kokacya, M.H.; Kurhan, F.; Oktay, G.; Ozer, C. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in patients with beta thalassemia major and their caregivers. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar]

- Maheri, A.; Sadeghi, R.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Tol, A.; Yaseri, M.; Rohban, A. Depression, Anxiety, and Perceived Social Support among Adults with Beta-Thalassemia Major: Cross-Sectional Study. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2018, 39, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Ahmadi, M.; S, P. Health Related Quality of Life, Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Patients with Beta-Thalassemia Major. Iran. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2015, 5, 193–205. [Google Scholar]

- Bizri, M.; Koleilat, R.; Akiki, N.; Dergham, R.; Mihailescu, A.M.; Bou-Fakhredin, R.; Musallam, K.M.; Taher, A.T. Quality of life, mood disorders, and cognitive impairment in adults with β-thalassemia. Blood Rev. 2024, 65, 101181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangi, K.; Shaleha, R.; Wijaya, E.; Birriel, B. Psychosocial Problems in People Living with Thalassemia: A Systematic Review. SAGE Open Nurs. 2025, 11, 23779608251323811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnaiyan, S.; Sylvia, J.; Kothandaraman, S.; Palanisamy, B. Quality of life and thalassemia in India: A scoping review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodashenas, M.; Mardi, P.; Taherzadeh-Ghahfarokhi, N.; Tavakoli-Far, B.; Jamee, M.; Ghodrati, N. Quality of Life and Related Paraclinical Factors in Iranian Patients with Transfusion-Dependent Thalassemia. J. Environ. Public. Health 2021, 2021, 2849163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, R.; Badawy, S.M. Health-related quality of life with standard and curative therapies in thalassemia: A narrative literature review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2024, 1532, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 236) | Study Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (n = 119) | 2025 (n = 117) | |||||

| n | % | % | p-Value | |||

| Gender | male | 102 | 43.2 | 47.1 | 39.3 | 0.230 |

| female | 134 | 56.8 | 52.9 | 60.7 | ||

| Age, years | mean (stand. dev.) | 43.3 (8.7) | 39.7 (8.5) | 46.9 (7.9) | <0.001 | |

| Family status | married | 184 | 78.0 | 47.1 | 59.8 | <0.001 |

| unmarried, divorced | 52 | 22.0 | 52.9 | 40.2 | ||

| Children | no | 77 | 32.6 | 11.8 | 53.8 | <0.001 |

| yes | 159 | 67.4 | 88.2 | 46.2 | ||

| Education level | minimum/no education | 21 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 9.4 | |

| secondary | 93 | 39.4 | 41.2 | 37.6 | 0.847 | |

| higher | 122 | 51.7 | 50.4 | 53.0 | ||

| Occupation | employed | 96 | 40.7 | 47.1 | 34.2 | 0.044 |

| unemployed (retired, student, etc.) | 140 | 59.3 | 52.9 | 65.8 | ||

| Body Mass Index | underweight | 9 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 5.1 | |

| normal | 165 | 69.9 | 73.1 | 66.7 | 0.421 | |

| overweight, obese | 62 | 26.3 | 24.4 | 28.2 | ||

| Family income, € | <1000 | 3 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.9 | |

| 1000–5000 | 50 | 21.2 | 21.0 | 21.4 | ||

| 5001–10,000 | 63 | 26.7 | 29.4 | 23.9 | 0.832 | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 96 | 40.7 | 37.8 | 43.6 | ||

| >20,000 | 24 | 10.2 | 10.1 | 10.3 | ||

| Thalassemia | α | 11 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 5.1 | 0.137 |

| β | 202 | 85.6 | 87.4 | 83.8 | ||

| microdrepanocytic anemia | 15 | 6.4 | 3.4 | 9.4 | ||

| other | 8 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 1.7 | ||

| Study Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 (n = 119) | 2025 (n = 117) | ||

| Scale | Mean ± Stand. Dev. | p-Value | |

| EQ-5D-3L Quality of Life (higher score ⇨ better QoL) | 0.85 ± 0.16 | 0.84 ± 0.15 | 0.791 |

| lower (score < 1.00) | 66.1% | 67.5% | 0.817 |

| excellent (score = 1.00) | 33.9% | 32.5% | |

| HADS, anxiety (higher score ⇨ high symptomatology) | 4.94 ± 4.13 | 5.07 ± 3.99 | 0.640 |

| normal (<8) | 75.6% | 74.4% | 0.961 |

| mild (8–10) | 13.4% | 15.4% | |

| moderate (10–14) | 7.6% | 7.7% | |

| severe (15–21) | 3.4% | 2.6% | |

| HADS, depression (higher score ⇨ high symptomatology) | 3.28 ± 3.54 | 4.14 ± 4.06 | 0.041 |

| normal (<8) | 87.4% | 83.8% | 0.491 |

| mild (8–10) | 8.4% | 7.7% | |

| moderate (10–14) | 3.4% | 5.1% | |

| severe (15–21) | 0.8% | 3.4% | |

| HADS, total (higher scale ⇨ high symptomatology) | 8.22 ± 7.16 | 9.21 ± 7.30 | 0.194 |

| normal (up to 16) | 85.7% | 86.3% | 0.892 |

| mild, moderate, severe (16+) | 14.3% | 13.7% | |

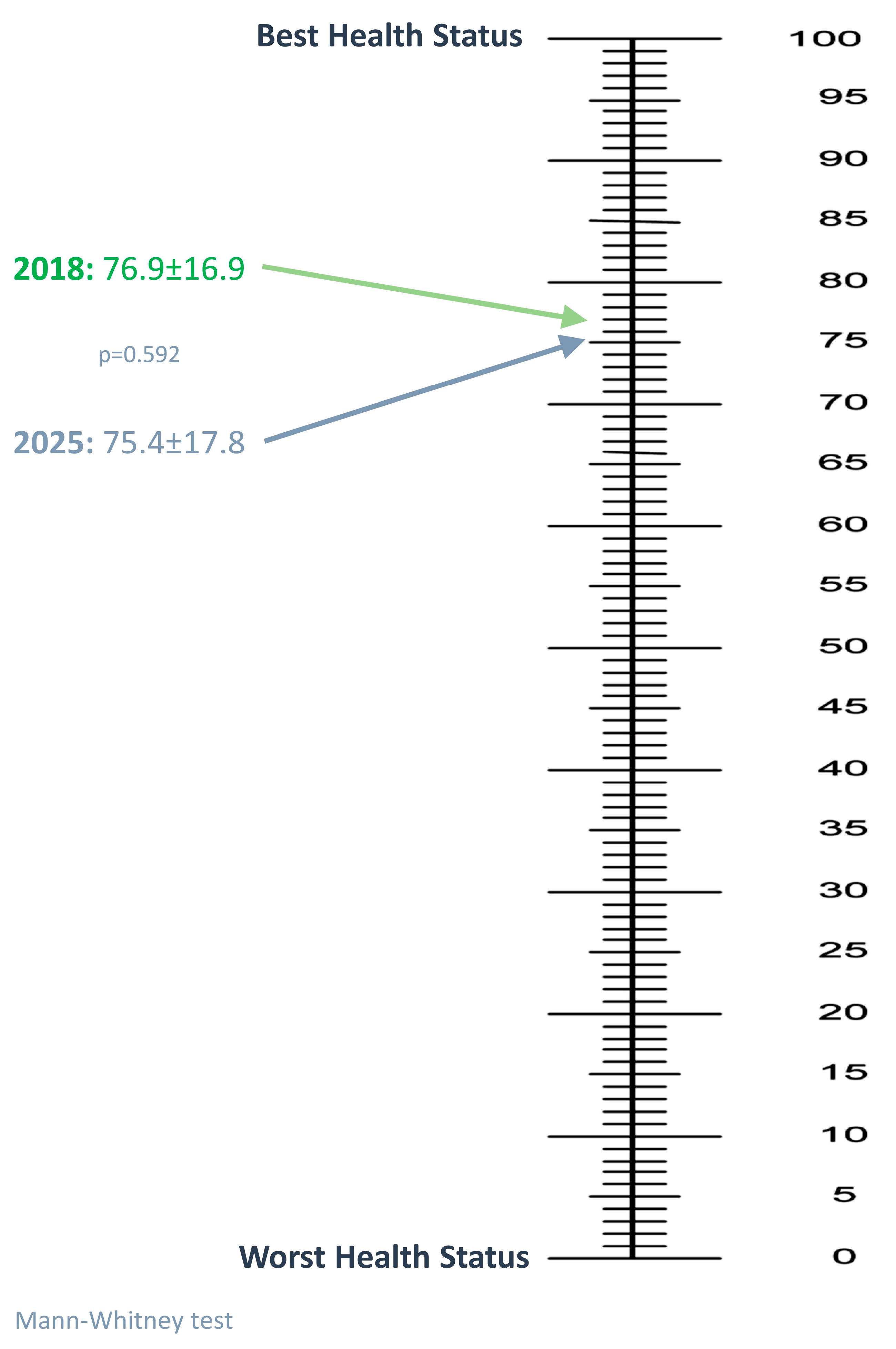

| EQ-VAS Score (Health Status) (Higher Score ⇨ Better Health Status) | EQ-5D-3L Quality of Life (Higher Score ⇨ Better QoL) | HADS, Anxiety (Higher Score ⇨ High Symptomatology) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| rho-Spearman | |||

| EQ-5D-3L Quality of Life (higher score ⇨ better QoL) | 0.520 * | ||

| HADS, anxiety (higher score ⇨ high symptomatology) | −0.497 * | −0.567 * | |

| HADS, depression (higher score ⇨ high symptomatology) | −0.474 * | −0.556 * | 0.668 * |

| HADS, total (higher scale ⇨ high symptomatology) | −0.538 * | −0.616 * | - |

| Patients with Lower QoL (Score < 1.00) Compared to Excellent QoL (Score = 1.00) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Model | 2nd Model | |||

| Odds Ratio (95% CIs) | p-Value | Odds Ratio (95% CIs) | p-Value | |

| Gender (females vs. males) | 1.22 (0.69–2.18) | 0.497 | 1.36 (0.68–2.74) | 0.387 |

| Age (by decade) | 1.15 (0.80–1.66) | 0.454 | 1.19 (0.76–1.87) | 0.457 |

| Family status (unmarried and divorced vs. married) | 0.92 (0.40–2.12) | 0.835 | 1.00 (0.38–2.65) | 0.995 |

| Children (yes vs. no) | 0.51 (0.24–1.06) | 0.071 | 0.40 (0.17–0.96) | 0.040 |

| Education level (by education level: minimum/no education, secondary, higher) | 0.96 (0.60–1.56) | 0.877 | 0.99 (0.57–1.72) | 0.970 |

| Occupation (unemployed vs. employed) | 1.86 (1.01–3.43) | 0.048 | 1.94 (0.94–3.98) | 0.072 |

| Body Mass Index (by category: underweight, normal, overweight/obese) | 1.16 (0.65–2.07) | 0.621 | 1.11 (0.57–2.18) | 0.753 |

| Family income (by level) | 0.80 (0.58–1.11) | 0.182 | 0.92 (0.64–1.33) | 0.656 |

| Years of study (2025 vs. 2018) | 0.90 (0.80–1.02) | 0.108 | ||

| HADS, anxiety score (by unit) | 1.26 (1.09–1.45) | 0.002 | ||

| HADS, depression score (by unit) | 1.11 (0.95–1.31) | 0.199 | ||

| EQ-5D-3L Quality of Life (by unit) | 0.97 (0.94–0.99) | 0.009 | ||

| Pseudo R2Nagelkerke | 0.082 | 0.392 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rikos, N.; Tzagkaraki, M.; Linardaki, A.; Moloudaki, M.; Linardakis, M. Temporal Changes in Quality of Life and Psychological Burden of Patients with Thalassemia: A Comparative Data Analysis from 2018 to 2025. Thalass. Rep. 2025, 15, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040011

Rikos N, Tzagkaraki M, Linardaki A, Moloudaki M, Linardakis M. Temporal Changes in Quality of Life and Psychological Burden of Patients with Thalassemia: A Comparative Data Analysis from 2018 to 2025. Thalassemia Reports. 2025; 15(4):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040011

Chicago/Turabian StyleRikos, Nikos, Marilena Tzagkaraki, Antigoni Linardaki, Maria Moloudaki, and Manolis Linardakis. 2025. "Temporal Changes in Quality of Life and Psychological Burden of Patients with Thalassemia: A Comparative Data Analysis from 2018 to 2025" Thalassemia Reports 15, no. 4: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040011

APA StyleRikos, N., Tzagkaraki, M., Linardaki, A., Moloudaki, M., & Linardakis, M. (2025). Temporal Changes in Quality of Life and Psychological Burden of Patients with Thalassemia: A Comparative Data Analysis from 2018 to 2025. Thalassemia Reports, 15(4), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/thalassrep15040011