An Insight into Role of Auditory Brainstem in Tinnitus: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Assessments

Abstract

1. Introduction

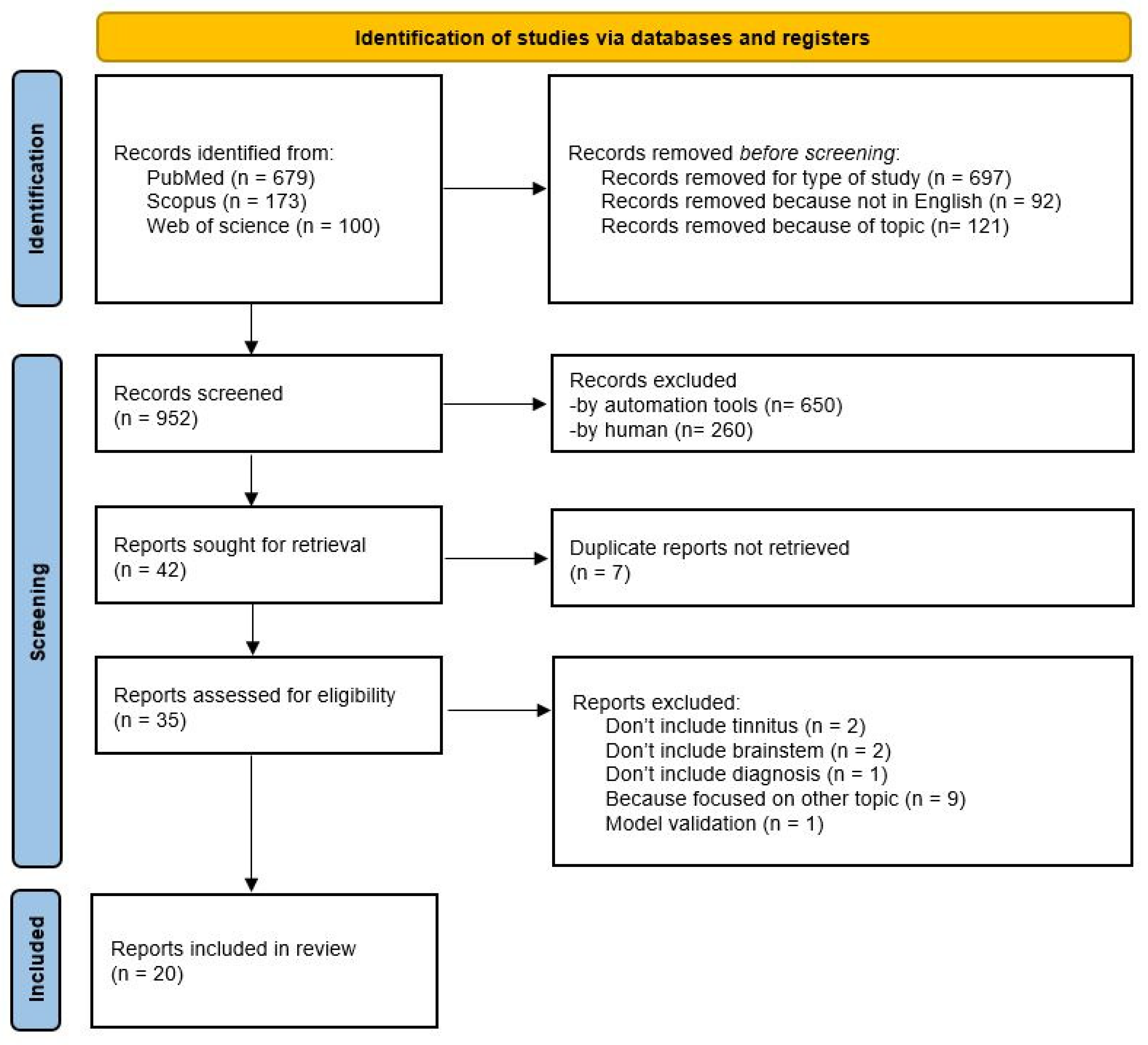

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Eligibility

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

Quality Assessment Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABR | Auditory brainstem response |

| ABRs | Auditory brainstem responses |

| AES | Auditory electrical stimulation |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BTT | Brainstem transmission time |

| CAP | Compound action potential |

| CN | Cochlear nucleus |

| DPOAEs | Distortion product otoacoustic emissions |

| EVAS | Enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome |

| fMRI | Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| GPIAS | Silent gap prepulse inhibition of the auditory startle reflex |

| IC | Inferior colliculus |

| MLAEP | Middle latency auditory evoked potential |

| MML | Minimum masking level |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NTEs | Non-tinnitus ears |

| OAE | Otoacoustic emissions |

| PICA | Posterior inferior cerebellar artery |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| RI | Residual inhibition |

| SIT | Subjective idiopathic tinnitus |

| TEs | Tinnitus ears |

| UCL | Uncomfortable loudness level |

| 3D-FIESTA | Three-dimensional fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition |

References

- Baguley, D.; McFerran, D.; Hall, D. Tinnitus. Lancet 2013, 382, 1600–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetoni, A.R.; Di Cesare, T.; Settimi, S.; Sergi, B.; Rossi, G.; Malesci, R.; Marra, C.; Paludetti, G.; De Corso, E. The evaluation of global cognitive and emotional status of older patients with chronic tinnitus. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e02074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malesci, R.; Brigato, F.; Di Cesare, T.; Del Vecchio, V.; Laria, C.; De Corso, E.; Fetoni, A.R. Tinnitus and Neuropsychological Dysfunction in the Elderly: A Systematic Review on Possible Links. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogeni, P.; Maihoub, S.; Molnár, A. Speech recognition thresholds correlate with tinnitus intensity in individuals with primary subjective tinnitus. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1672762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggermont, J.J.; Roberts, L.E. The neuroscience of tinnitus. Trends Neurosci. 2004, 27, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, L.E.; Eggermont, J.J.; Caspary, D.M.; Shore, S.E.; Melcher, J.R.; Kaltenbach, J.A. Ringing ears: The neuroscience of tinnitus. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 14972–14979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, N.F.; Gao, Y.; Licari, F.; Kaltenbach, J.A. Comparison and contrast of noise-induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus and inferior colliculus. Hear. Res. 2013, 295, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalappa, B.I.; Brozoski, T.J.; Turner, J.G.; Caspary, D.M. Single unit hyperactivity and bursting in the auditory thalamus of awake rats directly correlates with behavioural evidence of tinnitus. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 5065–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gendt, M.J.; Boyen, K.; de Kleine, E.; Langers, D.R.; van Dijk, P. The relation between perception and brain activity in gaze-evoked tinnitus. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 17528–17539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feldmann, H. Time patterns and related parameters in masking of tinnitus. Acta Otolaryngol. 1983, 95, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, M.J. Variability in matches to subjective tinnitus. J. Speech Hear. Res. 1983, 26, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.E.; Moffat, G.; Baumann, M.; Ward, L.M.; Bosnyak, D.J. Residual inhibition functions overlap tinnitus spectra and the region of auditory threshold shift. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2008, 9, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, A.M.; Jones, D.M.; Davis, B.R.; Slater, R. Parametric studies of tinnitus masking and residual inhibition. Br. J. Audiol. 1983, 17, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Anschuetz, L.; Hall, D.A.; Caversaccio, M.; Wimmer, W. Susceptibility to Residual Inhibition Is Associated with Hearing Loss and Tinnitus Chronicity. Trends Hear. 2021, 25, 2331216520986303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulders, W.H.; Seluakumaran, K.; Robertson, D. Efferent pathways modulate hyperactivity in inferior colliculus. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 9578–9587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galazyuk, A.V.; Voytenko, S.V.; Longenecker, R.J. Long-lasting forward suppression of spontaneous firing in auditory neurons: Implication to the residual inhibition of tinnitus. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2017, 18, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, B.R.; Motts, S.D.; Mellott, J.G. Cholinergic cells of the pontomesencephalic tegmentum: Connections with auditory structures from cochlear nucleus to cortex. Hear. Res. 2011, 279, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetoni, A.R.; Lucidi, D.; Corso, E.; Fiorita, A.; Conti, G.; Paludetti, G. Relationship between Subjective Tinnitus Perception and Psychiatric Discomfort. Int. Tinnitus J. 2017, 20, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek, B.; Szczepek, A.J.; Hebert, S. Stress and tinnitus. HNO 2015, 63, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trevis, K.J.; McLachlan, N.M.; Wilson, S.J. Psychological mediators of chronic tinnitus: The critical role of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 204, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasabi, F.; Alosaimi, F.; Corrales-Terrón, M.; Wolters, A.; Strikwerda, D.; Smit, J.V.; Temel, Y.; Janssen, M.L.F.; Jahanshahi, A. Post-Mortem Analysis of Neuropathological Changes in Human Tinnitus. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoroff, S.M.; Kaltenbach, J.A. The Role of the Brainstem in Generating and Modulating Tinnitus. Am. J. Audiol. 2019, 28, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noreña, A.J. An integrative model of tinnitus based on a central gain controlling neural sensitivity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011, 35, 1089–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjamian, P.; Hall, D.A.; Palmer, A.R.; Allan, T.W.; Langers, D.R. Neuroanatomical abnormalities in chronic tinnitus in the human brain. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 45, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Available online: https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool.html (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Mahmoudian, S.; Lenarz, M.; Esser, K.H.; Salamat, B.; Alaeddini, F.; Dengler, R.; Farhadi, M.; Lenarz, T. Alterations in early auditory evoked potentials and brainstem transmission time associated with tinnitus residual inhibition induced by auditory electrical stimulation. Int. Tinnitus J. 2013, 18, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, H.F.; Ribeiro, D.; Ribeiro, S.F.; Trigueiros, N.; Caria, H.; Borrego, L.; Pinto, I.; Papoila, A.L.; Hoare, D.J.; Paço, J. Audiological biomarkers of tinnitus in an older Portuguese population. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 933117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makar, S.K.; Mukundan, G.; Gore, G. Auditory System Synchronization and Cochlear Function in Patients with Normal Hearing with Tinnitus: Comparison of Multiple Feature with Longer Duration and Single Feature with Shorter Duration Tinnitus. Int. Tinnitus J. 2017, 21, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.H.; Chung, J.H.; Min, H.J.; Cho, S.H.; Park, C.W.; Lee, S.H. Clinical Application of 3D-FIESTA Image in Patients with Unilateral Inner Ear Symptom. Korean J. Audiol. 2013, 17, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, S.; Faghih Habibi, A.; Panahi, R.; Pastadast, M. Cochlear and brainstem audiologic findings in normal hearing tinnitus subjects in comparison with non-tinnitus control group. Acta Med. Iran. 2014, 52, 822–826. [Google Scholar]

- Kehrle, H.M.; Granjeiro, R.C.; Sampaio, A.L.; Bezerra, R.; Almeida, V.F.; Oliveira, C.A. Comparison of auditory brainstem response results in normal-hearing patients with and without tinnitus. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008, 134, 647–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagólski, O.; Stręk, P. Comparison of characteristics observed in tinnitus patients with unilateral vs bilateral symptoms, with both normal hearing threshold and distortion-product otoacoustic emissions. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017, 137, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, H.J.; An, Y.H.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, J.E.; Yoon, J.H. Comparisons of auditory brainstem response and sound level tolerance in tinnitus ears and non-tinnitus ears in unilateral tinnitus patients with normal audiograms. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskunoglu, A.; Orenay-Boyacioglu, S.; Deveci, A.; Bayam, M.; Onur, E.; Onan, A.; Cam, F.S. Evidence of associations between brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) serum levels and gene polymorphisms with tinnitus. Noise Health 2017, 19, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanting, C.P.; De Kleine, E.; Bartels, H.; Van Dijk, P. Functional imaging of unilateral tinnitus using fMRI. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008, 128, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Chen, Y.F.; Yang, T.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Liu, J.H.; Lo, T.S.; Cheng, Y.F. Impact of tinnitus on chirp-evoked auditory brainstem response recorded using maximum length sequences. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157, 2180–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, E.C. Is it necessary to differentiate tinnitus from auditory hallucination in schizophrenic patients? J. Laryngol. Otol. 2005, 119, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, B.; Brors, D.; Koch, O.; Schäfers, M.; Kahle, G. Magnetic resonance imaging in patients with sudden hearing loss, tinnitus and vertigo. Otol. Neurotol. 2001, 22, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos Filha, V.A.; Samelli, A.G.; Matas, C.G. Middle Latency Auditory Evoked Potential (MLAEP) in Workers with and without Tinnitus who are Exposed to Occupational Noise. Med. Sci. Monit. 2015, 21, 2701–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussen, C.F.; Pandey, A. Neurootological differentiations in endogenous tinnitus. Int. Tinnitus J. 2009, 15, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Filha, V.A.; Samelli, A.G.; Matas, C.G. Noise-induced tinnitus: Auditory evoked potential in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Clinics 2014, 69, 487–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, L.; Oliver, P.; Mitchell, R.; Sinha, L.; Kearney, J.; Saad, D.; Nodal, F.R.; Bajo, V.M. Optimization of the Operant Silent Gap-in-Noise Detection Paradigm in Humans. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2024, 23, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzalira, R.; Maudonnet, O.A.; Pereira, R.G.; Ninno, J.E. The contribution of otoneurological evaluation to tinnitus diagnosis. Int. Tinnitus J. 2004, 10, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Devolder, P.; Keppler, H.; Keshishzadeh, S.; Taghon, B.; Dhooge, I.; Verhulst, S. The role of hidden hearing loss in tinnitus: Insights from early markers of peripheral hearing damage. Hear. Res. 2024, 450, 109050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanting, C.P.; de Kleine, E.; Langers, D.R.; van Dijk, P. Unilateral tinnitus: Changes in connectivity and response lateralization measured with FMRI. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciello, F.; Pisani, A.; Rinaudo, M.; Cocco, S.; Paludetti, G.; Fetoni, A.R.; Grassi, C. Noise-induced auditory damage affects hippocampus causing memory deficits in a model of early age-related hearing loss. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 178, 106024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramhall, N.F. Use of the auditory brainstem response for assessment of cochlear synaptopathy in humans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2021, 150, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacxsens, L.; De Pauw, J.; Cardon, E.; van der Wal, A.; Jacquemin, L.; Gilles, A.; Michiels, S.; Van Rompaey, V.; Lammers, M.J.W.; De Hertogh, W. Brainstem evoked auditory potentials in tinnitus: A best-evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 941876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, R.; Jiang, H.; Tian, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wu, H. Typewriter Tinnitus: Value of ABR as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Indicator. Ear Hear. 2023, 44, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavusoglu, M.; Cılız, D.S.; Duran, S.; Ozsoy, A.; Elverici, E.; Karaoglanoglu, R.; Sakman, B. Temporal bone MRI with 3D-FIESTA in the evaluation of facial and audiovestibular dysfunction. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2016, 97, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Kawarabayashi, T.; Shibata, M.; Kasahara, H.; Makioka, K.; Sugawara, T.; Oka, H.; Ishizawa, K.; Amari, M.; Ueda, T.; et al. High levels of plasma neurofilament light chain correlated with brainstem and peripheral nerve damage. J. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 463, 123137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galazyuk, A.V.; Wenstrup, J.J.; Hamid, M.A. Tinnitus and underlying brain mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 20, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Strings | Number of Results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“tinnitus”[MeSH Terms] OR “tinnitus”[All Fields]) AND (“brain stem”[MeSH Terms] OR (“brain”[All Fields] AND “stem”[All Fields]) OR “brain stem”[All Fields] OR “brainstem”[All Fields] OR “brainstems”[All Fields] OR “brainstem s”[All Fields]) AND (“diagnosable”[All Fields] OR “diagnosi”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Terms] OR “diagnosis”[All Fields] OR “diagnose”[All Fields] OR “diagnosed”[All Fields] OR “diagnoses”[All Fields] OR “diagnosing”[All Fields] OR “diagnosis”[MeSH Subheading])) AND (2000/1/1:2025/6/30[pdat]) | 679 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (tinnitus) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (brainstem) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (diagnosis)) AND PUBYEAR > 1999 AND PUBYEAR < 2026 | 173 |

| Web of Science | Tinnitus (All Fields) and brainstem (All Fields) and diagnosis (All Fields) | 100 |

| First Author, Title (IT/EN), Journal (Year) | Database | Topic Aim of the Study | Type of Study, Sample Size, Tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Saeid Mahmoudian, Alterations in early auditory evoked potentials and brainstem transmission time associated with tinnitus residual inhibition induced by auditory electrical stimulation. International Tinnitus Journal (2013) [27] | PubMed | The main aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of RI induced by auditory electrical stimulation (AES) in the primary auditory pathways using early auditory-evoked potentials in subjective idiopathic tinnitus subjects. | Type of study: “cross-sectional and randomized, placebo-controlled trial” Sample size: 44 Tools: Electrocochleography, ABR, brainstem transmission time pre/post-AES | Patients with residual inhibition showed significant changes in compound action potential amplitude and in the I/V and III/V amplitude ratios. The brainstem transmission time was reduced after stimulation in those who experienced residual inhibition. |

| (2) Haúla F. Haider, Audiological biomarkers of tinnitus in an older Portuguese population. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. (2022) [28] | Scopus | The main aim of this study was to evaluate the associations between audiological parameters and the presence or severity of tinnitus, to improve tinnitus diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 122 Tools: Audiometry, psychoacoustic evaluation, ABR, DPOAEs, Tinnitus Handicap Inventory | Exposure to noise and hearing loss were associated with a higher risk of tinnitus. An abrupt onset and moderate-to-severe hyperacusis were also related to more severe tinnitus. Increased wave I amplitude appeared protective, while a higher V/I amplitude ratio was linked to a greater likelihood of moderate tinnitus. |

| (3) Sujoy Kumar Makar, Auditory System Synchronization and Cochlear Function in Patients with Normal Hearing With Tinnitus: Comparison of Multiple Feature with Longer Duration and Single Feature with Shorter Duration Tinnitus. International Tinnitus Journal (2017) [29] | PubMed | To observe cochlear and brainstem function in normal hearing ears with tinnitus using DPOAEs and ABR audiometry | Type of study: Case-control study. Sample size: 60 (control group: 30; study group: 30) Tools: Pure tone audiometry, tinnitus matching, DPOAEs, ABR latencies/Inter-peak Latency | Ears with tinnitus showed a reduction of DPOAE signal-to-noise ratio and amplitude, together with prolonged ABR latencies. Abnormalities of the III–V inter-peak latency were particularly associated with longer duration and more complex tinnitus. |

| (4) Jae Ho Oh, Clinical Application of 3D-FIESTA Image in Patients with Unilateral Inner Ear Symptom. Korean J Audiol (2013) [30] | Scopus | The purpose of this study was to introduce the clinical usefulness of three-dimensional fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition (3D-FIESTA) MRI in patients with unilateral ear symptoms. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 253 Tools: 3D-FIESTA MRI temporal bone | Imaging revealed a variety of abnormalities including acoustic neuroma, enlarged vestibular aqueduct syndrome, vascular aneurysms and other cochlear or nerve malformations. The technique proved useful for identifying subtle cochlear and retrocochlear pathologies. |

| (5) Shadman Nemati, Cochlear and Brainstem Audiologic Findings in Normal Hearing Tinnitus Subjects in Comparison with Non-Tinnitus Control Group. Acta Medica Iranica. (2014) [31] | PubMed | Present study was performed in order to better understanding of the probable causes of tinnitus and to investigate possible changes in the cochlear and auditory brainstem function in normal hearing patients with chronic tinnitus. | Type of study: cross-sectional, descriptive and analytic study Sample size: 25 (control group: 6, study group: 19) Tools: TEOAEs, ABR latencies/amplitudes | No significant differences were found in absolute wave latencies or interpeak intervals between tinnitus and control groups. Only the V/I amplitude ratio was significantly higher in tinnitus patients, suggesting a potential marker of altered brainstem function. |

| (6) Helga M. Kehrle, Comparison of Auditory Brainstem Response Results in Normal-Hearing Patients With and Without Tinnitus. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2008) [32] | PubMed | To perform an electrophysiological evaluation of the auditory nerve and the auditory brainstem function of patients with tinnitus and normal-hearing thresholds using the ABR. | Type of study: case-control study Sample size: 75 (control group: 38, study group: 37) Tools: ABR latency & interpeak measures | Almost half of the tinnitus patients showed at least one abnormal ABR parameter. Waves I, III and V were significantly delayed compared with controls, and the V/I amplitude ratio was higher in tinnitus despite being within normal limits. |

| (7) Olaf Zagólski, Comparison of characteristics observed in tinnitus patients with unilateral vs. bilateral symptoms, with both normal hearing threshold and distortion-product otoacoustic emissions. Acta Oto-Laryngologica (2016) [33] | PubMed | The study was to determine the differences between tinnitus characteristics observed in patients with unilateral vs. bilateral symptoms and normal hearing threshold, as well as normal results of DPOAEs. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 380 Tools: Tympanometry, ABR, psychoacoustic tests | Bilateral tinnitus was more often associated with longer symptom duration, greater sound hypersensitivity and higher pitch compared with unilateral cases. Noise exposure was the most frequent reported trigger in bilateral tinnitus. |

| (8) Hyun Joon Shim, Comparisons of auditory brainstem response and sound level tolerance in tinnitus ears and non-tinnitus ears in unilateral tinnitus patients with normal audiograms. PLoS ONE (2017) [34] | PubMed | Recently, “hidden hearing loss” with cochlear synaptopathy has been suggested as a potential pathophysiology of tinnitus in individuals with a normal hearing threshold. Several studies have demonstrated that subjects with tinnitus and normal audiograms show significantly reduced ABR wave I amplitudes compared with control sub- jects, but normal wave V amplitudes, suggesting increased central auditory gain. We aimed to reconfirm the “hidden hearing loss” theory through a within-subject comparison of wave I and wave V amplitudes and UCL, which might be decreased with increased central gain, in TEs and non-TEs. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 61 (control group: 18, study group: 43) Tools: ABR wave I & V, UCL tests | The study did not find conclusive ABR evidence of cochlear synaptopathy. However, patients with tinnitus showed reduced sound tolerance, which may indicate increased central gain even with normal audiograms. |

| (9) Aysun Coskunoglu, Evidence of associations between brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) serum levels and gene polymorphisms with tinnitus. Noise Health (2017) [35] | Scopus | This study aims to investigate whether there is any role of BDNF changes in the pathophysiology of tinnitus. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 94 (control group: 42, study group: 65) Tools: Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, psychiatric interview, BDNF gene & serum analysis | Patients with tinnitus had lower serum BDNF levels compared with controls. No significant association was found between BDNF gene polymorphisms and tinnitus, suggesting that reduced BDNF might play a role in its pathophysiology. |

| (10) C.P. Lanting, Functional imaging of unilateral tinnitus using fMRI. Acta Oto-Laryngologica (2008) [36] | PubMed | The major aim of this study was to determine tinnitus-related neural activity in the central auditory system of unilateral tinnitus subjects and compare this to control subjects without tinnitus. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 22 (control group: 12, study group: 10) Tools: fMRI (IC & auditory cortex) | Functional imaging showed a prominent role of the inferior colliculus in tinnitus-related neural activity, highlighting its importance in central auditory processing of tinnitus. |

| (11) Hsiang-Hung Lee, Impact of tinnitus on chirp-evoked auditory brainstem response recorded using maximum length sequences. Acoustical Society of America (2025) [37] | Scopus | The etiopathogenesis in audiovestibular symptoms can be elusive, despite extensive differential diagnosis. This article addresses the value of MRI in analysis of the complete audiovestibular pathway. | Type of study: retrospective Sample size: 40 (control group: 20, study group: 20) Tools: Chirp ABR amplitudes/latencies at various rates | Tinnitus patients demonstrated larger wave I amplitudes, prolonged wave V latencies and longer interpeak intervals compared with controls, indicating altered brainstem auditory processing. |

| (12) Eui-Cheol Nam, Is it necessary to differentiate tinnitus from auditory hallucination in schizophrenic patients? The Journal of Laryngology & Otology (2005) [38] | Scopus | This study examined whether the differentiation of tinnitus from auditory hallucination is necessary for the proper management of these symptoms in schizophrenic patients. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 15 Tools: Pure tone audiometry, ABR | Auditory brainstem responses were abnormal only in patients with pure auditory hallucinations, supporting the need to distinguish tinnitus from hallucinations in the clinical evaluation of schizophrenia. |

| (13) Bernhard Schick, Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients with Sudden Hearing Loss, Tinnitus and Vertigo. Otology & Neurotology (2001) [39] | Scopus | The etiopathogenesis in audiovestibular symptoms can be elusive, despite extensive differential diagnosis. This article addresses the value of MRI in analysis of the complete audiovestibular pathway. | Type of study: retrospective Sample size: 354 Tools: Contrast-enhanced MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging detected a variety of abnormalities including microangiopathic brain changes, cerebellopontine angle tumors, demyelinating lesions and inflammatory processes, confirming its high diagnostic value in audiovestibular disorders. |

| (14) Valdete Alves Valentins dos Santos Filha, Middle Latency Auditory Evoked Potential (MLAEP) in Workers with and without Tinnitus who are Exposed to Occupational Noise. Med Sci Monit (2015) [40] | PubMed | Tinnitus is an important occupational health concern, but few studies have focused on the central auditory pathways of workers with a history of occupational noise exposure. Thus, we analyzed the central auditory pathways of workers with a history of occupational noise exposure who had normal hearing threshold, and compared MLAEP in those with and without noise-induced tinnitus. | Type of study: cross-sectional Sample size: 60 (control group: 30, study group: 30) Tools: Audiometry, MLAEP | Both tinnitus and non-tinnitus groups had prolonged MLAEP latencies, but tinnitus patients tended to show more amplitude alterations, suggesting subtle central auditory processing impairment due to occupational noise. |

| (15) Claus-F. Claussen, Neurootological Differentiations in Endogenous Tinnitus. International Tinnitus Journal (2009) [41] | Scopus | Vertigo and tinnitus are very frequent complaints. Often, we find multisensory syndromes combined with tinnitus, hearing impairment, vertigo, and nausea. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 757 Tools: Multisensory neuro-otological tests | Results indicated that tinnitus is often part of a complex multisensory and central disorder, with a predominantly central rather than peripheral pathophysiological background. |

| (16) Valdete Alves Valentins dos Santos-Filha, Noise-induced tinnitus: auditory evoked potential in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Clinics (2014) [42] | PubMed | Evaluation of the central auditory pathways in workers with noise- induced tinnitus with normal hearing thresholds, compared the ABR results in groups with and without tinnitus and correlated the tinnitus location to the auditory brainstem response findings in individuals with a history of occupational noise exposure. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 60 Tools: Audiometry, ABR | Although mean ABR latencies did not significantly differ, tinnitus patients showed more frequent qualitative abnormalities in lower brainstem responses, particularly in bilateral tinnitus cases. |

| (17) Louis Negri, Optimization of the Operant Silent Gap-in-Noise Detection Paradigm in Humans. J. Integr. Neurosci. (2024) [43] | PubMed | In the auditory domain, temporal resolution is the ability to respond to rapid changes in the envelope of a sound over time. Silent gap-in-noise detection tests assess temporal resolution. Whether temporal resolution is impaired in tinnitus and whether those tests are useful for identifying the condition is still debated. The aim is to revisit these questions by assessing the silent gap-in-noise detection performance of human participants. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 71 Tools: Gap detection tasks, GPIAS, ABR | Tinnitus participants had higher gap detection thresholds at certain frequencies compared with controls. ABR latencies varied with tinnitus severity, suggesting impaired temporal resolution but limited individual diagnostic value. |

| (18) Raquel Mezzalira, The Contribution of Otoneurological Evaluation to Tinnitus Diagnosis. International Tinnitus Journal (2004) [44] | Scopus | The aim of this study is to analyze the contribution of otoneurological evaluation in the diagnosis of tinnitus. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 195 Tools: Clinical history, audiometry, vestibular tests | Otoneurological evaluation contributed to reaching an etiological diagnosis in most cases, supporting its usefulness in routine tinnitus workup. |

| (19) Pauline Devolder, The role of hidden hearing loss in tinnitus: Insights from early markers of peripheral hearing damage. Hearing Research (2024) [45] | Scopus | This study investigated three potential markers of peripheral hidden hearing loss in subjects with tinnitus: extended high-frequency audiometric thresholds, the ABR, and the envelope following response | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 54 Tools: High-frequency audiometry, ABR, Envelope following response, speech-in-noise | No significant differences in markers of synaptopathy were found between tinnitus and controls. Older tinnitus patients performed better in low-pass filtered speech-in-noise tests, possibly linked to hyperacusis. |

| (20) Cornelis P. Lanting, Unilateral Tinnitus: Changes in Connectivity and Response Lateralization Measured with fMRI. PLoS ONE (2014) [46] | Scopus | Tinnitus is a percept of sound that is not related to an acoustic source outside the body. For many forms of tinnitus, mechanisms in the central nervous system are believed to play a role in the pathology. In this work were specifically assessed possible neural correlates of unilateral tinnitus. | Type of study: not specified Sample size: 30 (control group: 16, study group: 14) Tools: fMRI (auditory network connectivity) | Patients with tinnitus showed reduced lateralization of auditory responses and decreased connectivity between brainstem and cortex. The cerebellar vermis appeared to participate in tinnitus-related plasticity. |

| Author, Year [Ref. Num] | EPHPP Scores | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB | D | C | B | DC | DO | Overall | |||||||

| R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | R1 | R2 | ||

| Saeid Mahmoudian, 2013 [27] | W | W | M | W | W | W | M | M | S | M | W | W | W |

| Haúla F. Haider, 2022 [28] | W | W | W | W | W | M | M | M | S | S | W | W | W |

| Sujoy Kumar Makar, 2017 [29] | W | W | M | W | W | M | S | S | W | W | M | M | W |

| Jae Ho Oh, 2013 [30] | M | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | M | W | M | M | W |

| Shadman Nemati, 2014 [31] | W | W | W | W | W | W | M | M | M | W | M | W | W |

| Helga M. Kehrle, 2008 [32] | S | M | M | S | W | W | W | W | M | W | M | M | W |

| Olaf Zagólski, 2016 [33] | M | M | W | M | W | W | M | W | W | M | n/a | n/a | W |

| Hyun Joon Shim, 2017 [34] | W | W | W | W | W | W | S | M | M | M | M | M | W |

| Aysun Coskunoglu, 2017 [35] | M | M | M | M | M | M | S | M | S | M | M | S | S |

| C.P. Lanting, 2008 [36] | W | W | W | M | W | W | M | M | M | W | M | M | W |

| Hsiang-Hung Lee, 2025 [37] | W | W | M | M | M | M | S | S | S | M | M | M | M |

| Eui-Cheol Nam, 2005 [38] | W | W | n/a | n/a | W | M | S | M | W | W | M | W | W |

| Bernhard Schick, 2001 [39] | M | M | W | M | W | W | W | W | M | W | M | W | W |

| Valdete Alves Valentins dos Santos Filha, 2015 [40] | M | M | W | M | W | W | M | M | M | M | W | W | W |

| Claus-F. Claussen, 2009 [41] | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | M | M | M | S |

| Valdete Alves Valentins dos Santos Filha, 2014 [42] | M | W | W | M | W | W | S | S | W | W | M | M | W |

| Louis Negri, 2024 [43] | M | M | M | M | S | S | S | S | S | S | M | M | S |

| Raquel Mezzalira, 2004 [44] | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | W | W |

| Pauline Devolder, 2024 [45] | W | W | W | W | W | W | M | M | S | S | M | M | W |

| Cornelis P. Lanting, 2014 [46] | W | W | W | M | W | W | S | S | S | M | M | W | W |

| 3D-FIESTA | MRI |

|---|---|

| 1. Acoustic neuroma | 1. Various degrees of subcortical and periventricular microangiopathic gliosis |

| 2. EVAS | 2. Pontine infarctions |

| 3. PICA aneurysm | 3. Loops of the inferior anterior cerebellar artery |

| 4. Inner ear anomaly | 4. Acoustic neuroma |

| 5. Hypoplastic 8th n. | 5. Inflammation of the eight cranial nerve |

| 6. Vertebral a. calcification | 6. Meningioma at the cerebellopontine angle |

| 7. Pons infarction | 7. Cerebellar infarctions |

| 8. Epidermal cyst | 8. Labyrinthine hemorrhage |

| 9. Pachymeningiosis affecting the internal auditory meatus | |

| 10. Cerebral multiple sclerosis | |

| 11. Cerebral venous dysplasia | |

| 12. Parietal meningioma | |

| 13. Cerebral atrophy with ventricular dilatation | |

| 14. Cochlea enhancement | |

| 15. Perilymphatic fistula | |

| 16. Pontine multiple sclerosis | |

| 17. Pontine venous dysplasia | |

| 18. Cerebral sarcoidosis | |

| 19. Cerebral cavernoma | |

| 20. Temporal lobe mucoepidermoid metastasis | |

| 21. Aqueduct stenosis | |

| 22. Ventricular cyst | |

| 23. Subdural hematoma | |

| 24. Posttraumatic cerebral gliosis | |

| 25. Cholesterin granuloma of the petrous bone apex | |

| 26. Chondrosarcoma of the petrous bone apex | |

| 27. Cystadenolymphoma of the parotid gland |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Freda, G.; Ciorba, A.; Serra, N.; Malesci, R.; Stomeo, F.; Bianchini, C.; Pelucchi, S.; Picciotti, P.M.; Maiolino, L.; Asprella Libonati, G.; et al. An Insight into Role of Auditory Brainstem in Tinnitus: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Assessments. Audiol. Res. 2025, 15, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060149

Freda G, Ciorba A, Serra N, Malesci R, Stomeo F, Bianchini C, Pelucchi S, Picciotti PM, Maiolino L, Asprella Libonati G, et al. An Insight into Role of Auditory Brainstem in Tinnitus: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Assessments. Audiology Research. 2025; 15(6):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060149

Chicago/Turabian StyleFreda, Giovanni, Andrea Ciorba, Nicola Serra, Rita Malesci, Francesco Stomeo, Chiara Bianchini, Stefano Pelucchi, Pasqualina Maria Picciotti, Luigi Maiolino, Giacinto Asprella Libonati, and et al. 2025. "An Insight into Role of Auditory Brainstem in Tinnitus: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Assessments" Audiology Research 15, no. 6: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060149

APA StyleFreda, G., Ciorba, A., Serra, N., Malesci, R., Stomeo, F., Bianchini, C., Pelucchi, S., Picciotti, P. M., Maiolino, L., Asprella Libonati, G., & Fetoni, A. R. (2025). An Insight into Role of Auditory Brainstem in Tinnitus: A Systematic Review of Diagnostic Assessments. Audiology Research, 15(6), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres15060149