Abstract

Background: Hip fractures represent a major clinical challenge, particularly in elderly and frail patients, where postoperative pain control must balance effective analgesia with motor preservation to facilitate early mobilization. Various regional anesthesia techniques are used in this setting, including the pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block, fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB), femoral nerve block (FNB), and quadratus lumborum block (QLB), yet optimal strategies remain debated. Objectives: To systematically review the efficacy, safety, and clinical applicability of major regional anesthesia techniques for pain management in hip fractures, including considerations of fracture type, surgical approach, and functional outcomes. Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and the virtual library of the Hospital Central de la Defensa “Gómez Ulla” up to March 2025. Inclusion criteria were RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses evaluating regional anesthesia for hip surgery in adults. Risk of bias in RCTs was assessed using RoB 2.0, and certainty of evidence was evaluated using the GRADE approach. Results: Twenty-nine studies were included, comprising RCTs, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. PENG block demonstrated superior motor preservation and reduced opioid consumption compared to FICB and FNB, particularly in intracapsular fractures and anterior surgical approaches. FICB and combination strategies (PENG+LFCN or sciatic block) may provide broader analgesic coverage in extracapsular fractures or posterior approaches. The overall risk of bias across RCTs was predominantly low, and certainty of evidence ranged from moderate to high for key outcomes. No significant safety concerns were identified across techniques, although reporting of adverse events was inconsistent. Conclusions: PENG block appears to offer a favorable balance of analgesia and motor preservation in hip fracture surgery, particularly for intracapsular fractures. For extracapsular fractures or posterior approaches, combination strategies may enhance analgesic coverage. Selection of block technique should be tailored to fracture type, surgical approach, and patient-specific functional goals.

Keywords:

pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block; hip fracture regional analgesia; motor-sparing regional anesthesia; multimodal pain management in orthopedic surgery; fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB); intracapsular vs. extracapsular fractures; lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) block; opioid-sparing techniques 1. Introduction

Hip fractures are one of the most common causes of hospital admission, especially when the patients are elderly, clinically frail, or both. Their management requires agile and well-coordinated intervention across different specialties, with the anesthesiologist’s work being a fundamental pillar of perioperative management. Early analgesia not only significantly reduces pain but also directly influences the patient’s clinical and functional outcomes in the immediate postoperative period and over time [1,2].

In this context, regional anesthesia techniques have been gaining prominence and are now frequently used in daily clinical practice. It is not only about controlling pain, but also doing so without compromising motor function, avoiding the excessive use of opioids and allowing for faster recovery. Among the most commonly used techniques are femoral nerve block (FNB), fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB), and in recent years, pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block, which has aroused a keen interest in offering focused analgesia with significantly less muscle involvement [3].

However, the choice between these options is not simple. Each technique has its indications, limitations, and nuances. Factors such as the location of the fracture—whether intracapsular or extracapsular—the type of surgical approach intended, or even the experience of the anesthesiologist are all factors that could inevitably affect its effectiveness. The literature is extensive; however, the conclusions require a critical reading, as the results are not always comparable across studies [4].

This paper seeks to provide a reasoned review of the most current evidence on the main nerve blocks used in the management of patients with hip fractures.

Pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block and fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB) are regional anesthesia techniques routinely used for pain management in hip fractures and arthroplasties. Other blocks such as the femoral nerve block (FNB) or the femoralcutaneous block have also been options to be applied in the reviewed literature, although with less clinical frequency and lower impact and degree of recommendation (the femoralcutaneous block is of limited efficacy when performed in isolation) [5].

Another block is the quadratus lumborum nerve block, which has also been shown to be effective in reducing postoperative pain and opioid consumption. Periarticular local anesthetic infiltration has also been shown to be effective in reducing pain and opioid use. Although this is not a nerve block per se, it is a frequently used technique and has been shown to be comparable in efficacy to some nerve blocks, with the advantage of not causing significant motor weakness [6].

From the orthopedic surgeon’s perspective, the choice of regional anesthesia technique has a direct impact on surgical timing, patient mobility, and the incidence of perioperative complications such as delirium and falls. A well-selected block can reduce opioid burden, facilitate early rehabilitation, and support the goals of enhanced recovery pathways. Therefore, a deeper understanding of block selection is not only essential for anesthesiologists but also for orthopedic teams involved in perioperative planning and patient outcomes.

In this manuscript, these blocks will be compared in terms of effectiveness, risks, indications, pain control, opioid use, and recommendations, and potential combinations of techniques that could provide additional benefits are discussed.

The ultimate goal is to provide clarity in a field where clinical decisions must balance elements such as technical precision, individualization, and realistic functional outcomes.

2. Methodology

2.1. Design and Analysis

A systematic literature review was conducted, following the guidelines established by the PRISMA methodology for systematic reviews, with findings up to March 2025 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Search process (databases), filter points, and results obtained (2 researchers per database).

Search Terms: “Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) block”, “Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block (FICB)”, “Femoral nerve block”, “Lumbar Plexus block”, “Quadratus Lumborum block”, “Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block”, “Hip arthroplasty”, “Hip replacement surgery”, “Regional anesthesia for hip surgery”, “Postoperative pain management in hip arthroplasty”, “Analgesia regional selectiva en cadera”, “Ultrasound-guided hip nerve blocks”, “Anterior approach to hip analgesia”, “Posterior innervation of the hip”, “Obturator nerve block”, “Sciatic nerve block in hip procedures”, “Multimodal analgesia in orthopedic surgery”, “Minimizing opioid use in orthopedic patients”, “Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) hip protocols”, “Reduction of postoperative opioid consumption”, “Quadriceps motor-sparing techniques”, “Preservation of mobility after hip surgery”, “Functional recovery in elderly patients after arthroplasty”, “Delirium prevention in hip fracture surgery”, “Peripheral nerve block combinations in hip surgery”, “Pain scales in postoperative orthopedic care”, “Comparative effectiveness of PENG vs. FICB”, “Adverse effects of hip nerve blocks”, “Nausea and vomiting in postoperative period”, “Complications of femoral nerve block”, “Hemodynamic stability during hip surgery”, “Patient satisfaction after regional anesthesia”, “Mobilization time after hip surgery”, “Safety profile of PENG block”, “Indications for combining PENG with sciatic nerve block”, “Fascia iliaca vs. PENG block in hip fracture”, “Selective sensory block in hip analgesia”.

Search sources: A systematic search of scientific articles was carried out in high-impact databases such as PubMed.gov (U.S. National Library of Medicine—National Center for Biotechnology Information), ClinicalKey publications, the Scopus and Web of Science databases, and the virtual library of the HCD “Gómez Ulla CSDVE”.

Search topics: Clinical and experimental studies (randomized, prospective and/or retrospective studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses) on regional anesthesia to be used in clinical practice for effective pain control and comprehensive patient management in hip surgeries and arthroplasties.

2.2. Regulated Search and Selection Process

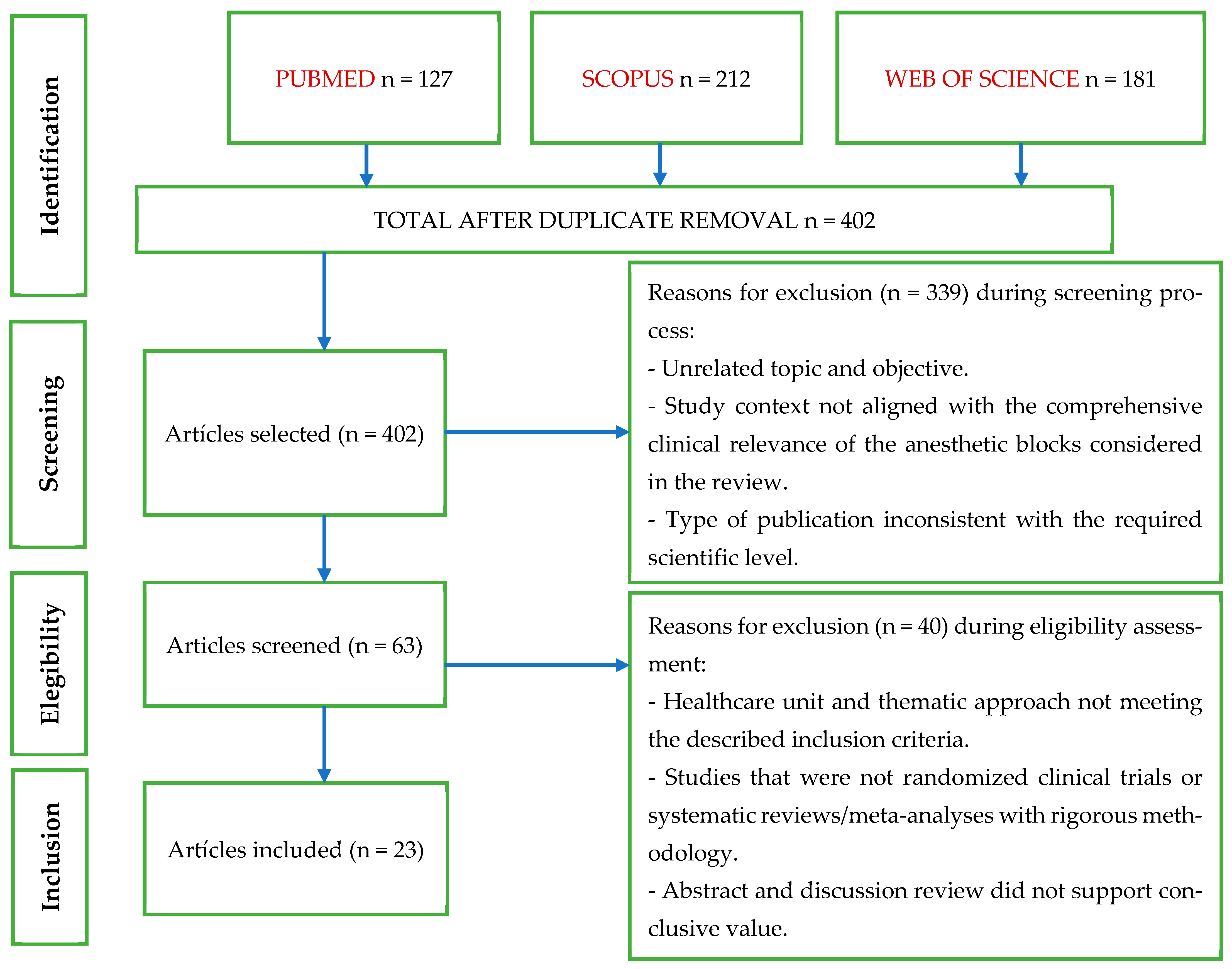

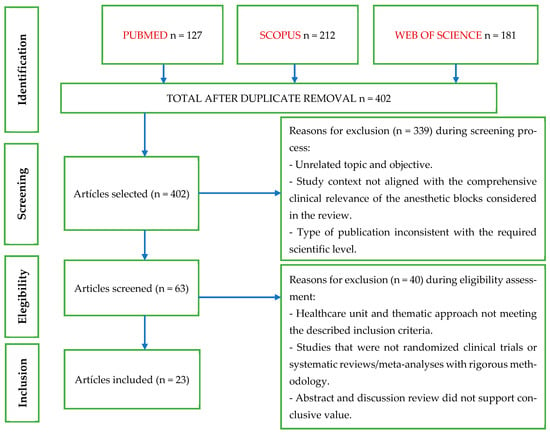

The study selection process was conducted according to PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Figure 1 summarizes the flow of records through the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion phases.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the bibliographic selection process.

2.3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Table 2 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied.

Table 2.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

2.4. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias of the included randomized controlled trials was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2) tool (Table 3), which assesses five domains of potential bias (for systematic reviews and meta-analyses included in the synthesis, no formal bias assessment was performed).

Table 3.

Risk of bias analysis (RCTs).

- 1.

- Bias arising from the randomization process,

- 2.

- Bias due to deviations from intended interventions,

- 3.

- Bias due to missing outcome data,

- 4.

- Bias in the measurement of the outcome,

- 5.

- Bias in the selection of the reported result.

Each study was independently reviewed, and risk of bias was categorized as low risk, some concerns, or high risk across each domain, with an overall risk rating derived accordingly.

Most of the included studies were rated as low risk of bias across all domains. A few studies presented some concerns related to randomization procedures or outcome reporting. However, no study was found to have a high risk of bias.

2.5. Certainty of Evidence Assessment (GRADE)

The certainty of evidence for each key outcome in this systematic review was assessed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations) framework. The outcomes evaluated included postoperative pain reduction, opioid consumption, motor preservation (quadriceps strength), time to ambulation or functional recovery, and adverse effects such as falls and postoperative nausea.

For each outcome, the following five domains were systematically considered:

- Risk of bias (based on the Cochrane RoB 2.0 tool),

- Inconsistency (heterogeneity across study results),

- Indirectness (applicability of the evidence to the target population and setting),

- Imprecision (precision of estimates, including confidence intervals and sample size considerations),

- Publication bias (suspected or detected through available data).

The certainty of the evidence was categorized as high, moderate, low, or very low, following the GRADE approach. The assessment was performed by two authors independently, with discrepancies resolved through discussion.

2.6. Forest Plots

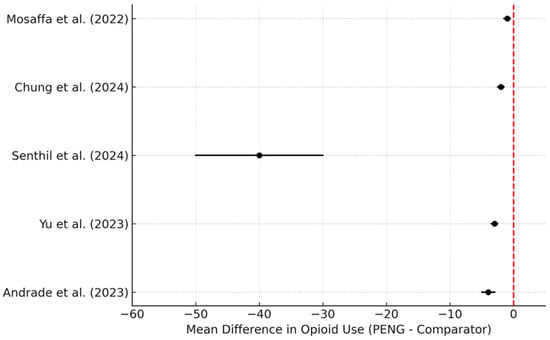

2.6.1. Forest Plot—24-Hour Opioid Consumption

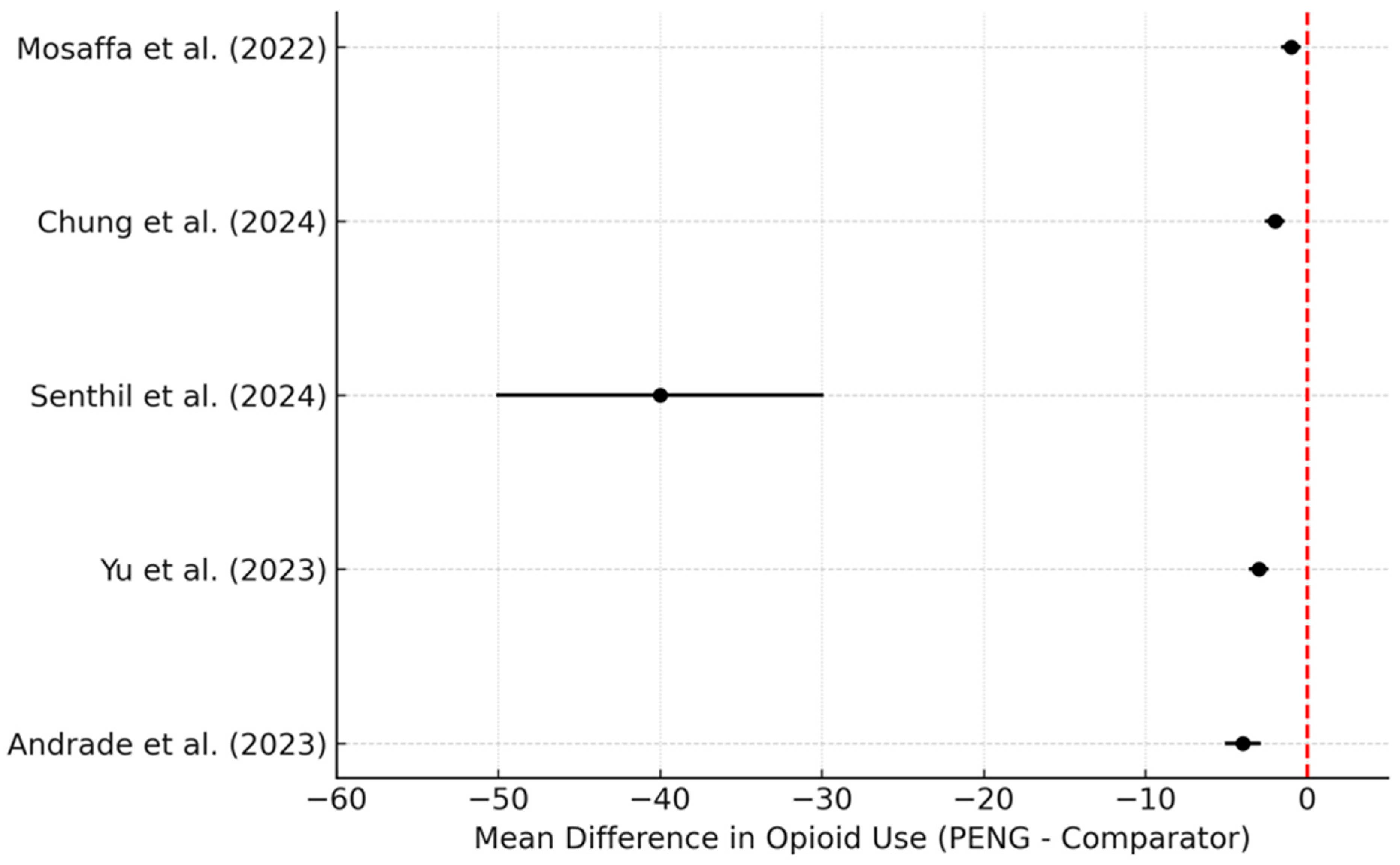

The use of PENG blocks has been consistently associated with lower opioid requirements in the first 24 h after hip fracture surgery compared to traditional blocks. For instance, Mosaffa et al. [11] found a significant reduction in morphine consumption in the PENG group compared to the fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB). Similarly, Chung et al. [9] reported lower fentanyl use (0.441 mg vs. 0.611 mg, p < 0.05) in the PENG group versus no block. Senthil et al., and Chaudhary K et al. [16] confirmed that patients receiving a PENG block required 213 µg of fentanyl on average, versus 255 µg in the FICB group. Yu et al. [24] and Andrade et al. [25] also showed statistically significant reductions in opioid use in favor of the PENG block.

The forest plot below (Figure 2) illustrates the mean differences in 24 h opioid consumption (in morphine or fentanyl equivalents), with all five studies favoring the PENG block over comparators.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of 24 h opioid consumption. Mean differences (PENG–comparator) with 95% confidence intervals. Negative values (red dotted line) favor the PENG block [9,11,16,24,25].

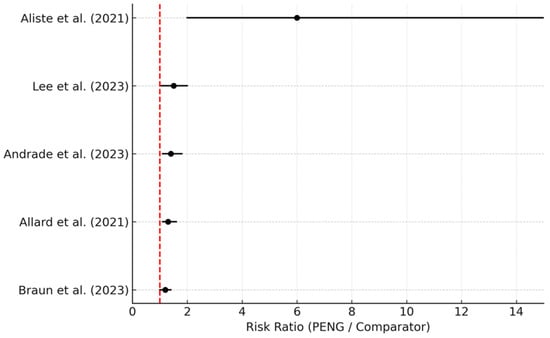

2.6.2. Forest Plot—Quadriceps Strength Preservation:

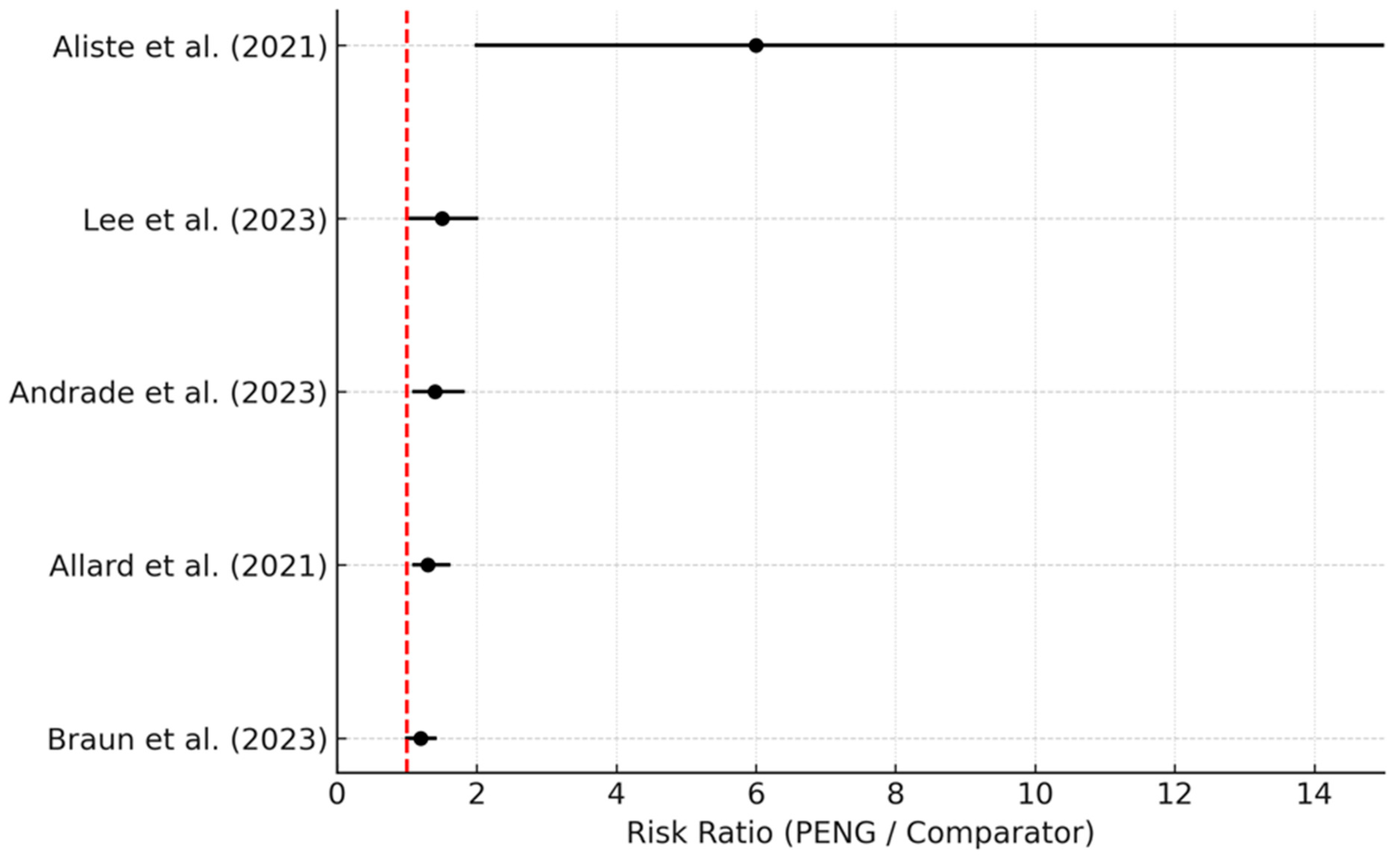

An important clinical advantage of the PENG block is motor sparing, which allows for better preservation of quadriceps muscle strength. Aliste et al. [8] demonstrated that 75% of patients maintained quadriceps strength with PENG blocks versus only 15% with suprainguinal FICBs. Similarly, Lee et al. [9] found 80% motor preservation with PENG blocks compared to 43% with lumbar plexus blocks. Andrade et al. [25], Allard et al. [18], and Aslan et al. [26] also supported superior quadriceps preservation with PENG blocks, improving the potential for early mobilization and reduced postoperative falls.

The forest plot below (Figure 3) shows the risk ratios for preserved quadriceps strength, with all included studies indicating a benefit of the PENG block over comparator techniques.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of preserved quadriceps strength. Risk ratios (PENG/comparator) with 95% confidence intervals. Values above 1 (red dotted line) favor the PENG block [8,9,18,20,25].

2.7. Study Selection and Data Presentation

The selection of studies for inclusion was based on predefined eligibility criteria. Each included study was reviewed in detail, and data were extracted into structured tables that summarize key characteristics, interventions, outcomes, and conclusions. Quantitative results are reported in Section 3, and qualitative conclusions are drawn in the Discussion based on the extracted data.

2.8. Effect Measures and Data Synthesis

For each outcome (e.g., postoperative pain, opioid consumption, quadriceps strength, time to ambulation, and adverse events), we extracted effect measures such as mean difference (MD), risk ratio (RR), or percentage differences, as reported in the primary studies. These effect measures were tabulated and summarized descriptively in Section 3.

No formal meta-analysis was performed in this review, as the heterogeneity of study designs, outcomes, and methodologies precluded statistical pooling. Consequently, no statistical models, measures of heterogeneity (e.g., I2), or assessments of publication bias (e.g., funnel plots) were conducted. Sensitivity analyses and meta-regression were not applicable to this synthesis.

2.9. Aditional Methodological Information

This systematic review was not prospectively registered in a protocol repository (e.g., PROSPERO), and no formal protocol was prepared prior to its initiation. This limitation is acknowledged in Section 2.

While prospective registration in platforms such as PROSPERO is encouraged for systematic reviews, our study did not undergo this process due to its exploratory nature and the absence of meta-analytic synthesis at the time of design. Given that our aim was to perform a qualitative synthesis of existing literature on regional anesthesia techniques in hip fracture management—with a focus on clinical applicability rather than statistical pooling of outcomes—we prioritized methodological rigor and adherence to PRISMA guidelines throughout the review process. Furthermore, the evolving clinical relevance of the topic and the rapid emergence of new techniques warranted timely analysis and dissemination without delay. Nonetheless, we acknowledge this limitation and have ensured full transparency in our methodology and inclusion criteria.

As no protocol was registered, no amendments were applicable or necessary during the course of this review.

This review received no financial support, sponsorship, or funding from any external organizations, academic institutions, or industry partners. All authors conducted this research independently, and there were no financial or non-financial influences on the research process or conclusions.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to this research.

2.10. Data Availability

- Template data collection forms: Not applicable; data extraction was performed manually based on predefined eligibility criteria.

- Data extracted from included studies: Available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

- Data used for all analyses: Available upon reasonable request.

- Analytic code: Not applicable, as no meta-analyses or statistical code were generated.

- Other materials: No additional materials beyond those included in the manuscript and supplementary files are available.

3. Results

A total of 29 studies were included in this systematic review, comprising randomized controlled trials (RCTs), meta-analyses, and systematic reviews.

The majority of studies compared the pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block with other regional techniques such as the fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB), femoral nerve block (FNB), lumbar plexus block (LPB), and quadratus lumborum block (QLB).

In this section, each study selected from the reviewed literature is presented individually (Table 4), in order to subsequently use the available information in the ensuing discussion.

Table 4.

Grouping and description of the publications analyzed in the review.

PENG blocks demonstrated a consistent reduction in quadriceps weakness compared to FICBs and FNBs, with studies reporting significantly lower rates of motor block at 3 and 6 h postoperatively. Several RCTs and meta-analyses showed that PENG blocks reduced opioid consumption in the first 24 h compared to FICBs, although results for pain scores were more variable, with some studies reporting comparable analgesia between techniques.

Combination strategies, such as PENG+LFCN or PENG+sciatic nerve blocks, were associated with improved analgesic coverage and better motor preservation in specific surgical contexts, such as total hip arthroplasty. In contrast, studies comparing PENG blocks with QLBs yielded mixed results, with QLBs showing marginally lower opioid consumption in some cases but no clear advantage in motor preservation.

Regarding fracture type, limited data suggest that PENG blocks may be particularly beneficial for intracapsular fractures, while a combination of PENG blocks and additional blocks may be needed for extracapsular fractures.

No study reported a significant increase in major adverse events associated with PENG blocks, although the reporting of adverse effects was inconsistent across studies.

A methodological quality assessment of the included studies was performed following PRISMA criteria, and the results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Methodological analysis of the reviewed literature (PRISMA methodology).

The final GRADE ratings are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

GRADE Assessment—certainty of evidence.

4. Discussion

Proper postoperative pain management in patients undergoing hip surgery is a challenge in regional anesthesiology. Three techniques were extensively studied in recent literature: femoral nerve block (FNB), pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block, and fascia iliaca block (FICB) [7,8,27]. Selecting the appropriate block not only impacts pain control but also early functional recovery, opioid requirements, and potential postoperative complications. Other techniques, such as quadratus lumborum block or lumbar plexus block, are reported in the literature; however, they are not as common in clinical practice [22,23].

Regarding effectiveness and perioperative pain control, PENG block has been shown to be more effective in controlling postoperative pain compared to FICB and femoral block [8,9,10,11,27,28,29], particularly when early mobilization, reduced quadriceps weakness, and improved positioning for spinal anesthesia are quantitatively assessed [28]. In patients with intertrochanteric fractures, PENG blocks showed lower pain scores during exercise at 6 h postoperatively compared to FICBs and a lower consumption of fentanyl and remifentanil [19]. Furthermore, in total hip arthroplasty surgeries, PENG block combined with lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) block provided better pain control and lower opioid consumption compared to FICB [10].

Several studies have shown that PENG blocks provide effective analgesia in the immediate and mid-term postoperative period, comparable to or superior to FICBs and FNBs. A recent meta-analysis [28] demonstrated that PENG block significantly reduces opioid consumption in the first 24 h compared to FICB (p = 0.008) [15]. Similarly, in a randomized study, PENG block reduced dynamic pain at 6 h postoperatively compared to FICB (p < 0.001) [8]. However, some clinical trials found no significant differences in pain scores at 12 and 24 h between PENG block and FICB [14,17].

Femoral block, on the other hand, is a technique widely supported in the literature but has the limitation of producing significant motor weakness. In a comparative trial, patients with FNBs had a higher incidence of quadriceps weakness compared to those receiving PENG blocks (90% vs. 50%, p = 0.004) [16].

There is literature supporting the trend that PENG block prolongs the time to analgesia request by approximately 3/4 h compared to no block (3.82 h, p = 0.05) [12].

Regarding risks and preservation of hip function and mobility, PENG block is associated with a lower incidence of quadriceps weakness compared to FICB and femoral block. It also showed significant preservation of quadriceps strength compared to FICB. Additionally, it preserves motor function better than femoral block, facilitating early postoperative rehabilitation [10,27,28].

A key aspect of PENG block is its ability to preserve motor function, unlike FNB and, to a lesser extent, FICB. In a clinical trial, 60% of PENG block patients maintained intact quadriceps strength, compared to 0% in the FNB group (p < 0.001). This is highly relevant in frail patients or in accelerated recovery protocols (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery, ERAS), where early mobilization is a priority [12,13,15].

FICB, on the other hand, can affect mobility in a variable manner depending on the spread of the anesthetic. Although the suprainguinal technique improves the spread of the block to the lumbar plexus, the risk of transient motor weakness persists [11,13].

PENG block has been shown to significantly reduce postoperative opioid consumption compared to FICB and femoral block. Several studies support the fact that patients receiving PENG blocks required fewer rescue opioids [13,24,25] compared to those receiving FICBs.

PENG block has been shown to be superior to FICB and FNB in reducing opioid consumption. In a systematic review, the PENG block group decreased morphine requirements by 50% compared to the control group (p < 0.001). This effect is crucial for reducing adverse effects such as postoperative delirium, nausea, and respiratory depression in elderly patients [12,15].

Regarding adverse effects and complications, the three most studied blocks (PENG block, FICB, and FNB) have a favorable safety profile. However, FNB is associated with an increased risk of falls due to quadriceps weakness, especially in geriatric patients [12]. In contrast, PENG block and FICB have less motor impairment, although the latter may be unpredictable in its anatomical propagation. PENG block has shown a lower incidence of adverse effects such as postoperative nausea and vomiting, with rates of 3% versus 10% in the non-blockade group, respectively (p < 0.05) [12,27].

Other blocks considered in the literature but less frequently applied in daily clinical practice include quadratus lumborum block (QLB) and lumbar plexus block (LPB), which are established as regional anesthesia techniques used for postoperative pain management in hip surgery [21].

These techniques have been compared with PENG blocks, and the findings under review have been conclusive. As previously stated, the PENG block is known to provide effective analgesia while preserving motor function, which facilitates early mobilization.

On the other hand, the quadratus lumborum (QLB) presents tangible advantages such as effective analgesia with relative preservation of muscle strength, which may facilitate early mobilization. There are manuscripts that have demonstrated that QLB reduces opioid consumption and postoperative pain scores. However, the technique can be more complex and requires a learning curve for proper execution. Furthermore, some studies have found no significant differences in opioid consumption compared to other blocks [22]. Regarding lumbar plexus block (LPB), despite achieving good perioperative analgesic efficacy, a significant and unavoidable disadvantage of LPB is the motor weakness it can induce, which can delay early mobilization and increase the risk of falls [20,21].

In addition to the above, the PENG block and QLB are effective options for postoperative analgesia in hip surgery, with the PENG block standing out for its ability to preserve motor function. The LPB, although effective in pain control, may limit early mobilization due to induced motor weakness [23,26].

Regarding block combinations, given that the PENG block does not fully cover the lateral innervation of the hip, some studies have proposed combining it with the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (LFCN) block. Liang et al. [24] compared PENG+LFCN with the suprainguinal FICB and found that the combination allowed for earlier ambulation (19.6 h vs. 26.5 h, p < 0.01) and a greater degree of hip flexion in the first 48 h. On the other hand, the combination of PENG block with sciatic block has been explored in posterior hip surgery, since PENG does not block the posterior innervation of the joint. This strategy could optimize analgesia without compromising motor function [29].

Finally, the precise indication for the use of the appropriate block in intra vs. extracapsular fractures will be addressed based on the reviewed literature; in patients with intracapsular fractures [28] scheduled for early surgery, a PENG block should be the first choice due to its selectivity and motor preservation. In extracapsular fractures, FICB may be more beneficial, although in fragile patients or those at high risk of falls, PENG block combined with another block should be considered to optimize analgesia without compromising mobility. In conclusion, the combination of PENG with sciatic block or LFCN block has been shown to improve analgesia in extracapsular fractures, being a valid option for surgeries with posterior approach or in patients with hypersensitivity in the lateral region of the thigh [8,27,29], always taking into consideration the possible motor block associated with blocks such as the sciatic block; this is something that, as the literature shows, does not present clinical significance with the performance of PENG blocks.

Table 7 presents recommended regional anesthesia techniques for hip fracture surgery based on key clinical variables, including fracture type, patient fragility, and surgical approach. Recommendations are based on the current evidence reviewed in the systematic analysis.

Table 7.

Block recommendation and rationale—evidence and clinical variables.

Limitations of the Study

A key limitation of this systematic review is the lack of stratification by surgical approach (arthroplasty vs. internal fixation) in the majority of the included studies. The anatomical differences between these procedures—particularly the involvement of posterior innervation in osteosynthesis cases—may impact the effectiveness of different regional blocks. While some studies suggest that PENG block provides effective analgesia for anterior procedures like total hip arthroplasty, its efficacy in posterior approaches or extracapsular fracture fixation may be limited without adjunctive blocks (e.g., sciatic or lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block).

This variability introduces a potential confounding factor that could not be fully accounted for in our synthesis. Future research should prioritize stratifying results by surgical approach to provide clearer guidance for tailored analgesic strategies.

Although this systematic review includes not only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) but also systematic reviews and meta-analyses, particular attention was paid to the potential duplication of primary studies. Careful cross-checking of the included studies was conducted to ensure that individual trials were not counted more than once in the synthesis or the discussion of results. This approach aimed to avoid introducing bias and ensure the integrity and accuracy of the qualitative conclusions drawn from the reviewed literature.

One important limitation of this review lies in the limited capacity to explore sources of clinical heterogeneity among studies. Although general patterns were identified, important variables such as local anesthetic volume and concentration, specific needle approach, ultrasound guidance technique, and practitioner experience were inconsistently reported across trials. These factors likely influenced both analgesic outcomes and motor blockade profiles. Consequently, while the directionality of effect estimates was consistent across blocks, variations in technique and drug regimens may have contributed to observed differences in efficacy. Future trials should aim to standardize and explicitly report these procedural variables to allow for more accurate subgroup analyses and clinical comparisons.

Furthermore, the reporting of adverse events and complications was inconsistent across studies. While most studies did not report serious complications, the lack of standardized definitions and systematic reporting limits our ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding the safety profiles of the various regional blocks. This underscores the need for future trials with rigorous adverse event monitoring and standardized outcome reporting.

This systematic review was not prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database, and this has been acknowledged as a limitation.

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- The reviewed studies suggest that PENG block offers significant advantages over femoral and fascia iliaca blocks in terms of effective analgesia, motor preservation, and reduction of opioid consumption.

- If the primary goal is early mobility preservation, PENG block is superior to FNB and FICB.

- For more extensive analgesia, the combination of PENG+LFCN or PENG+sciatic block may be ideal in certain surgical scenarios.

- FICB remains a valid option, especially in surgeries with a wide lateral approach.

- FNB should be reserved for patients where motor weakness is not a concern, given its impact on the quadriceps

- 2.

- PENG block is associated with less muscle weakness and better postoperative pain control compared to fascia iliaca block, without significantly increasing the risk of complications.

- 3.

- The literature suggests that PENG is the block of choice for intracapsular fractures, while for extracapsular fractures, FICB may be more appropriate, or PENG may be complemented with additional blocks such as LFCN or sciatic block to improve the analgesic coverage provided to the patient. The choice should be individualized ac-cording to the type of fracture, the surgical approach, and the patient’s functional needs, always taking into consideration the motor limitations caused by exposed blocks, which have a lesser impact when PENG block is used.

- 4.

- Regarding the comparison of PENG with other less common blocks in clinical practice, there is little or no consensus, but some publications conclude that QLB may offer better postoperative analgesia in terms of lower opioid consumption, while PENG block may be superior in preserving motor function, facilitating early mobilization. The choice between these blocks should be based on the patient’s specific analgesia and motor preservation needs.

- 5.

- Individualization of treatment based on the type of fracture, surgical approach, and rehabilitation goals remains key in selecting the optimal analgesic strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.G.M. and I.A.V.; methodology, E.G.M.; software, E.G.M.; validation, E.G.M., R.A.P. and I.A.V.; formal analysis, E.G.M.; investigation, E.G.M. and D.R.M.; resources, E.G.M. and C.G.D.L.; data curation, E.G.M. and A.R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.M. and A.D.V.; writing—review and editing, E.G.M., J.M.M. and R.A.P.; visualization, E.G.M. and I.A.V.; supervision, E.G.M., A.R.M., I.A.V., A.D.V. and A.J.G.S.; project administration, E.G.M., A.J.G.S. and A.R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, S.L.; Zhang, S.Y.; Si, H.B.; Shen, B. Regional versus general anesthesia in older patients for hip fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2023, 18, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cunningham, D.J.; Paniagua, A.; LaRose, M.; Kim, B.; MacAlpine, E.; Wixted, C.; Gage, M.J. Hip Fracture Surgery: Regional Anesthesia and Opioid Demand. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2022, 30, e979–e988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guay, J.; Kopp, S. Peripheral nerve blocks for hip fractures in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 11, CD001159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Scala, V.A.; Lee, L.S.K.; Atkinson, R.E. Implementing Regional Nerve Blocks in Hip Fracture Programs: A Review of Regional Nerve Blocks, Protocols in the Literature, and the Current Protocol at The Queen’s Medical Center in Honolulu, HI. Hawaii J. Health Soc. Welf. 2019, 78 (11 Suppl. S2), 11–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garlich, J.M.; Pujari, A.; Moak, Z.; Debbi, E.; Yalamanchili, R.; Stephenson, S.; Stephan, S.; Polakof, L.; Little, M.; Moon, C.; et al. Pain Management with Early Regional Anesthesia in Geriatric Hip Fracture Patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 2043–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.R.; Ma, T.; Hu, J.; Yang, J.; Kang, P.D. Comparison between ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve group block and anterio quadratus lumborum block for total hip arthroplasty: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 7523–7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behrends, M.; Yap, E.N.; Zhang, A.L.; Kolodzie, K.; Kinjo, S.; Harbell, M.W.; Aleshi, P. Preoperative fascia iliaca block does not improve analgesia after arthroscopic hip surgery, but causes quadriceps muscle weakness: A randomized, double-blind trial. Anesthesiology 2018, 129, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliste, J.; Layera, S.; Bravo, D.; Jara, Á.; Muñoz, G.; Barrientos, C.; Wulf, R.; Brañez, J.; Finlayson, R.J.; Tran, Q. Randomized comparison between pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block and suprainguinal fascia iliaca block for total hip arthroplasty. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2021, 46, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.Y.; Chung, C.J.; Park, S.Y. Comparing the pericapsular nerve group block and the lumbar plexus block for hip fracture surgery: A single-center randomized double-blinded study. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrone, F.; Saglietti, F.; Galimberti, A.; Pezzi, A.; Umbrello, M.; Cuttone, G.; La Via, L.; Vetrugno, L.; Deana, C.; Girombelli, A. Pericapsular nerve group block plus lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block vs. fascia iliaca compartment block in hip replacement surgery. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosaffa, F.; Ramazani, M.; Salimi, A.; Samadpour, H.; Memary, E.; Mirkheshti, A. Comparison of Pericapsular Nerve Group Block and Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block in Patients With Hip Fracture: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Anesth. 2022, 76, 110582. [Google Scholar]

- Jeevendiran, A.; Suganya, S.; Sujatha, C.; Rajaraman, J.; Surya, R.; Asokan, A.; Radhakrishnan, A. Comparison of pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block with femoral nerve block for positioning during spinal anesthesia in hip fracture surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Cureus 2024, 16, e67196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavithra, B.; Balaji, R.; Kumaran, D.; Gayathri, B.; Kumaran, D.; Balasubramaniam, G. Anatomical landmark-guided PENG block versus fascia iliaca block for positioning patients with hip fractures: A randomized controlled study. Cureus 2024, 16, e56270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Wang, Q.; Hu, J.; Kang, P.; Yang, J. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block combined with local infiltration analgesia on postoperative pain after total hip arthroplasty: A prospective, double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Arthroplasty. 2023, 38, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natrajan, P.; Bhat, R.R.; Remadevi, R.; Joseph, I.R.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Paulose, T.D. Comparative Study to Evaluate the Effect of Ultrasound-Guided Pericapsular Nerve Group Block Versus Fascia Iliaca Compartment Block on the Postoperative Analgesic Effect in Patients Undergoing Surgeries for Hip Fracture under Spinal Anesthesia. Anesth. Essays Res. 2021, 15, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chaudhary, K.; Bose, N.; Tanna, D.; Chandnani, A. Ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block versus femoral nerve block for positioning during spinal anesthesia in proximal femur fractures: A randomized comparative study. Indian J. Anaesth. 2023, 67, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nuthep, L.; Klanarong, S.; Tangwiwat, S. The analgesic effect of adding ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve group block to suprainguinal fascia iliaca compartment block for hip fracture surgery: A prospective randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2023, 102, e35649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, C.; Pardo, E.; de la Jonquière, C.; Wynieck, A.; Soulier, A.; Faddoul, A.; Tsai, E.S.; Bonnet, F.; Verdonk, F. Comparison between femoral block and PENG block in femoral neck fractures: A cohort study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.; Tang, Y.; Tong, F.; Guo, H.; Zhang, X.L.; Zhou, L.; Ni, H.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J. The analgesic efficacy of pericapsular nerve group block in patients with intertrochanteric femur fracture: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Braun, A.S.; Peabody Lever, J.E.; Kalagara, H.; Piennette, P.D.; Arumugam, S.; Mabry, S.; Thurston, K.; Naranje, S.; Feinstein, J.; Kukreja, P. Comparison of Pericapsular Nerve Group (PENG) Block Versus Quadratus Lumborum (QL) Block for Analgesia After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty Under Spinal Anesthesia: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e50119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Et, T.; Korkusuz, M. Comparison of the pericapsular nerve group block with the intra-articular and quadratus lumborum blocks in primary total hip arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 2023, 76, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, E.; Kelly, T.; Wolf, B.J.; Hansen, E.; Brown, A.; Lautenschlager, C.; Wilson, S.H. Comparison of pericapsular nerve group and lateral quadratus lumborum blocks on cumulative opioid consumption after primary total hip arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Huang, H.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y. Is pericapsular nerve group block superior to other regional analgesia techniques in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. A systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2024, 24, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Shen, X.; Liu, H. The efficacy of pericapsular nerve group block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing hip surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1084532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andrade, P.P.; Lombardi, R.A.; Marques, I.R.; Braga, A.C.D.N.A.E.; Isaias, B.R.; Heiser, N.E. Pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block versus fascia iliaca compartment block for hip surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 2023, 73, 794–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, M.; Kilicaslan, A.; Gök, F.; Kekec, A.F.; Colak, T.S. Comparison of Pericapsular Nerve Group Block Combined with Lateral Femoral Cutaneous Nerve Block versus Anterior Quadratus Lumborum Block for Analgesia in Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Prospective, Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Braz. J. Anesthesiol. 2025, 75, 844643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yi, S.; Li, D.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Kong, M. Ultrasound-guided pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block for early analgesia in elderly patients with hip fractures: A single-center prospective randomized controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023, 23, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; An, J.; Qian, C.; Wang, Z. Efficacy and Safety of Pericapsular Nerve Group Block for Hip Fracture Surgery under Spinal Anesthesia: A Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2024, 2024, 6896066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santis, A.D.; Suhr, B.; Irizaga, G. What do we know about the PENG block for hip surgery? A narrative review. Colomb. J. Anestesiol. 2024, 52, e1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).