Fetal Safety of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose in Pregnancy: A Cardiotocography Study from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Italy

Abstract

1. Background

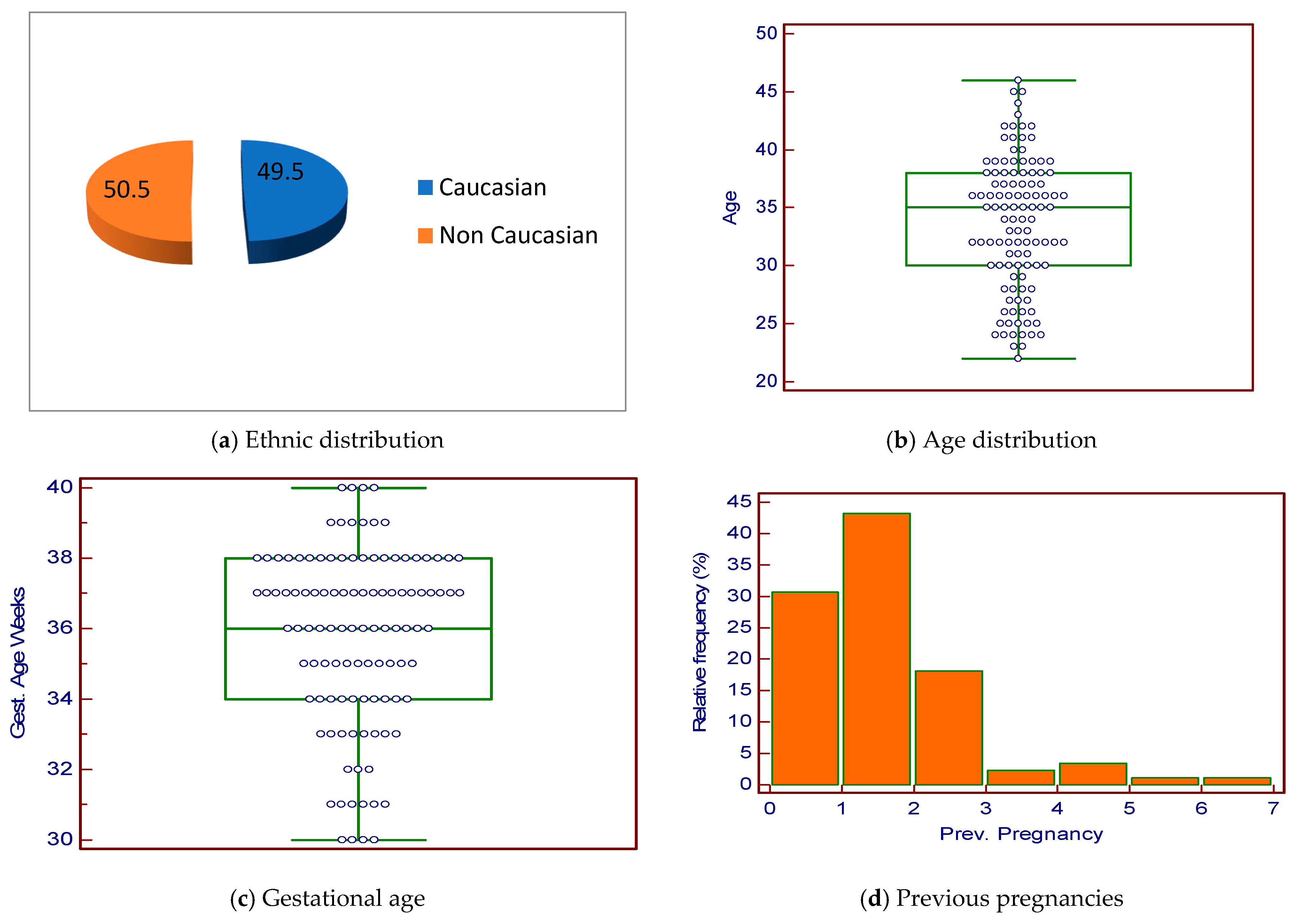

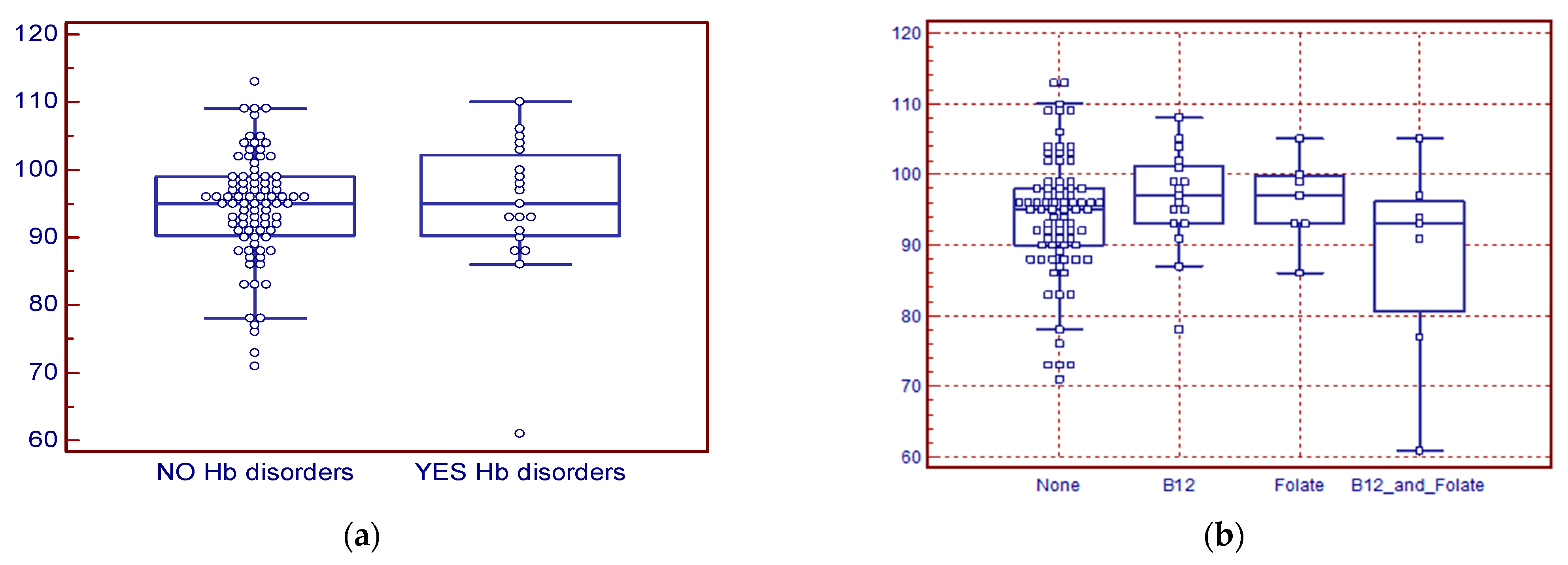

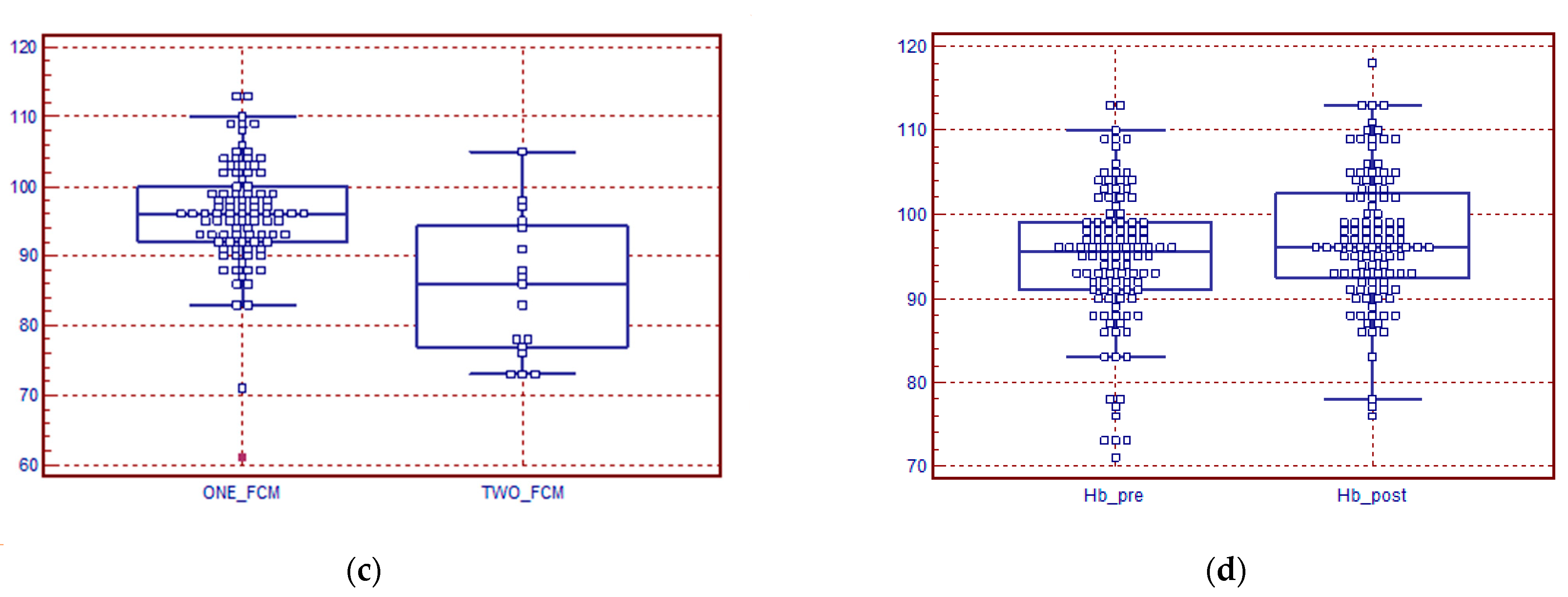

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017, 390, 1211–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, G.A.; Finucane, M.M.; De-Regil, L.M.; Paciorek, C.J.; Flaxman, S.R.; Branca, F.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Ezzati, M.; on behalf of Nutrition Impact Model Study Group (Anaemia). Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: A systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob. Health 2013, 1, e16–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daru, J.; Cooper, N.A.; Khan, K.S. Systematic review of randomized trials of the effect of iron supplementation on iron stores and oxygen carrying capacity in pregnancy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2016, 95, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Churchill, D.; Robinson, S.; Nelson-Percy, C.; Stanworth, S.J.; Knight, M. Association between maternal haemoglobin and stillbirth: A cohort study among a multi-ethnic population in England. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 179, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Abe, S.K.; Rahman, S.; Kanda, M.; Narita, S.; Bilano, V.; Ota, E.; Gilmour, S.; Shibuya, K. Maternal anemia and risk of adverse birth and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.F. Maternal anaemia and risk of mortality: A call for action. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e479–e480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Choudhury, M.K.; Choudhury, S.S.; Kakoty, S.D.; Sarma, U.C.; Webster, P.; Knight, M. Association between maternal anaemia and pregnancy outcomes: A cohort study in Assam, India. BMJ Glob. Health 2016, 1, e000026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirthan, J.P.A.; Somannavar, M.S. Pathophysiology and management of iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy: A review. Ann. Hematol. 2023, 3, 2637–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Shahid, S.; Noorani, S.; Fatima, I.; Jaffar, A.; Kashif, M.; Yazdani, N.; Khan, U.; Rizvi, A.; Nisar, M.I.; et al. Management of iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy: A midwife-led continuity of care model. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1400174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfalasi, H.A.; Kausar, S. Efficacy of Intravenous Iron Infusion in Gestational Iron Deficiency Anemia in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, During 2018–2019: A Retrospective Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e60185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dazelle, W.D.H.; Ebner, M.K.; Potarazu, S.; Kazma, J.; Ahmadzia, H. Oral versus intravenous iron for anemia in pregnancy: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Am. J. Perinatol. 2024, 43, 001–014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupte, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Puri, M.; Gopinath, P.M.; Wani, R.; Sharma, J.B.; Swami, O.C. A meta-analysis of ferric carboxymaltose versus other intravenous iron preparations for the management of iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2024, 46, e-rbgo21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Upadhyay, J.; Nandave, M.; Alsayari, A.; Alshehri, S.A.; Pukale, S.; Wahab, S.; Ahmad, W.; Rashid, S.; Ansari, M.N. Exploring progress in iron supplement formulation approaches for treating iron deficiency anemia through bibliometric and thematic analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wright, A.; Rahim, A.M.; Tan, K.H.; Tagore, S. Retrospective Study Comparing Treatment Outcomes in Obstetric Patients With Iron Deficiency Anemia Treated with and Without Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose. Cureus 2024, 16, e55713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimathi, G.; Revathy, R.; Bagepally, B.S.; Joshi, B. Clinical effectiveness of ferric carboxymaltose (iv) versus iron sucrose (iv) in treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Indian J. Med Res. 2024, 159, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral-Moreira, C.F.A.; Redezuk, G.; Pereira, B.G.; Borovac-Pinheiro, A.; Rehder, P.M. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy after Bariatric Surgery: Etiology, Risk Factors, and How to Manage It. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2023, 45, e562–e567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, R.P.; Lanzkron, S. Baby on board: What you need to know about pregnancy in the hemoglobin pathies. Hematol.-Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2012, 2012, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, V.M.; Cima, R.; Di Maggio, R.; Alga, M.L.; Gigante, A.; Longo, F.; Pasanisi, A.M.; Venturelli, D.; Cassinerio, E.; Casale, M.; et al. Thalassemias and Sickle Cell Diseases in Pregnancy: SITE Good Practice. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 948–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhide, A.; Meroni, A.; Frick, A.; Thilaganathan, B. The significance of meeting Dawes–Redman criteria in computerised antenatal fetal heart rate assessment. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 131, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampalija, T.; Bhide, A.; Heazell, A.; Sharp, A.; Lees, C. Computerized cardiotocography and Dawes–Redman criteria: How should we interpret criteria not met? Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 31, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandraharan, E.; Pereira, S.; Ghi, T.; Perez-Bonfils, A.G.; Fieni, S.; Jia, Y.-J.; Griffiths, K.; Sukumaran, S.; Ingram, C.; Reeves, K.; et al. International expert consensus statement on physiological interpretation of cardiotocograph (CTG): First revision (2024). Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 302, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, L.V.; Shah, M.; Bragg, B.N. APGAR Score. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470569/ (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Montgomery, K.S. Apgar Scores: Examining the Long-term Significance. J. Perinat. Educ. 2000, 9, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veneto Accesso Febbraio 2025. Available online: https://www.tuttitalia.it/veneto/statistiche/cittadini-stranieri-2024/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Trivedi, P.; Chitra, S.; Natarajan, S.; Amin, V.; Sud, S.; Vyas, P.; Singla, M.; Rodge, A.; Swami, O.C. Ferric Carboxymaltose in the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy: A Subgroup Analysis of a Multicenter Real-World Study Involving 1191 Pregnant Women. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2022, 2022, 5759740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.K.; Gautam, D.; Tolani, H.; Neogi, S.B. Clinical outcome post treatment of anemia in pregnancy with intravenous versus oral iron therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devalia, V.; Hamilton, M.S.; Molloy, A.M.; British Committee for Standards in Hematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorders. Br. J. Haematol. 2014, 166, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, R.; Moya, E.; Ataíde, R.; Truwah, Z.; Mzembe, G.; Mhango, G.; Demir, A.V.; Stones, W.; Randall, L.; Seal, M.; et al. Protocol and statistical analysis plan for a randomized controlled trial of the effect of intravenous iron on anemia in Malawian pregnant women in their third trimester (REVAMP—TT). Gates Open Res. 2023, 7, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, S.; Raval, D.; Shah, K.; Saxena, D. Cost-effectiveness analysis of parenteral iron therapy compared to oral iron supplements in managing iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women. Health Econ. Rev. 2024, 14, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmila, A.; Natarajan, S.; Chitra, T.V.; Pawar, N.; Kinjawadekar, S.; Firke, Y.; Murugesan, U.; Yadav, P.; Ohri, N.; Modgil, V.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Ferric Carboxymaltose in the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Multi- Center Real-World Study from India. J. Blood Med. 2022, 13, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.W.; Go, D.Y.; Lee, S.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Ko, E.J.; You, H.S.; Jang, Y.K. Comparative efficacy and safety of intravenous ferric carboxymaltose and iron sucrose for iron deficiency anemia in obstetric and gynecologic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2021, 100, e24571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasricha, S.-R.; Moya, E.; Ataíde, R.; Mzembe, G.; Harding, R.; Mwangi, M.N.; Zinenani, T.; Prang, K.-H.; Kaunda, J.; Mtambo, O.P.L.; et al. Ferric carboxymaltose for anemia in late pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, S.-R.; Mwangi, M.N.; Moya, E.; Ataide, R.; Mzembe, G.; Harding, R.; Zinenani, T.; Larson, L.M.; Demir, A.Y.; Nkhono, W.; et al. Ferric carboxymaltose versus standard-of-care oral iron to treat second-trimester anaemia in Malawian pregnant women: A randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1595–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khezri, R.; Rezaei, F.; Jahanfar, S.; Ebrahimi, K. Association between maternal anemia during pregnancy with low birth weight their infants. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busnelli, A.; Fabiani, C.; Acerboni, S.; Montefusco, S.M.; Di Simone, N.; Setti, P.E.L.; Bulfoni, A. Efficacy of ferric carboxymaltose for treatment of iron deficiency anemia diagnosed in the third trimester of pregnancy: A case-control study. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2023, 49, 1161–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langer, A.L.; Goggins, B.B.; Esrick, E.B.; Fell, G.; Berliner, N.; Economy, K.E. β-Thalassemia minor is associated with high rates of worsening anemia in pregnancy. Blood 2025, 145, 648–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, A.-d.-C.; Sabaratnam, A. FIGO Intrapartum Fetal Monitoring Expert Consensus Panel. Figo consensus guidelines on Intrapartum fetal monitoring. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2015, 131, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Intrapartum Fetal Surveillance Clinical Guideline, 4th ed.; Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: Victoria, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lovers, A.; Daumer, M.; Frasch, M.G.; Ugwumadu, A.; Warrick, P.; Vullings, R.; Pini, N.; Tolladay, J.; Petersen, O.B.; Lederer, C.; et al. Advancements in Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring: A Report on Opportunities and Strategic Initiatives for Better Intrapartum Care. Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2025, 132, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, I.; Hirono, Y.; Shima, E.; Yamamoto, H.; Yoshihara, K.; Kai, C.; Yoshida, A.; Uchida, F.; Kodama, N.; Kasai, S. Comparison and verification of detection accuracy for late deceleration with and without uterine contractions signals using convolutional neural networks. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1525266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis Jones, G.; Albert, B.; Cooke, W.; Vatish, M. Performance evaluation of computerized antepartum fetal heart rate monitoring: Dawes-Redman algorithm at term. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 65, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neri, S.; Zegarra, R.R.; Dininno, M.; Di Pasquo, E.; Tagliaferri, S.; Ghi, T. Interobserver agreement of intrapartum cardiotocography interpretation by midwives using current FIGO and physiology-based guidelines. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2024, 37, 2425758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.-S.; Choi, E.S.; Nam, Y.J.; Liu, N.W.; Yang, Y.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Ahn, K.H.; Hong, S.C. Real-time Classification of Fetal Status Based on Deep Learning and Cardiotocography Data. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magdoud, K.; Karoui, A.; Abouda, H.S.; Menjli, S.; Aloui, H.; Chanoufi, M.B. Decreased fetal movement: Maternal characteristics and pregnancy outcome. Tunis. Med. 2023, 101, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Watanabe, M.; Watanabe, N.; Fukase, M.; Yamanouchi, K.; Nagase, S. Correlation between the 5-tier fetal heart rate pattern classification at delivery and Apgar scores. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2025, 51, e16199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Condition | Condition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 14 (13.3%) | Tuberculosis | 2 (1.9%) |

| Hypotiroidism | 12 (11.4%) | Pulmonary thromboembolism | 1 (0.9%) |

| Hypertension | 8 (7.6%) | Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (0.9%) |

| Multiple Abortions | 4 (3.8%) | Severe asthma | 1 (0.9%) |

| CNS disease | 3 (2.9%) | Previous Fallot tetralogy | 1 (0.9%) |

| Tyroiditis | 3 (2.9%) | Sleeve gastrectomy | 1 (0.9%) |

| Drug | Drug | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral iron | 37 (35.2%) | Antibiotics | 10 (6.5%) |

| Folates supplementation | 35 (33.3%) | Antihypertensives | 8 (7.6%) |

| B12 supplementation | 31 (29.5) | Anti-inflammatories | 8 (7.6%) |

| Insulin | 14 (13.3%) | Tapazole | 3 (2.9%) |

| Eutirox | 12 (11.4%) | Corticosteroids | 2 (1.9%) |

| Symptom | Results | Symptom | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthenia | 87 (82.9%) | Fatigability | 75 (71.4%) |

| Mucocutaneous pallor | 52 (49.8%) | Hypotension | 31 (29.5%) |

| Tachycardya | 11 (10.5%) | Dyspnea | 7 (6.7%) |

| Edema of the legs | 7 (6.7%) | Irritability | 1 (1.9%) |

| Parameter | Results | Parameter | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hb before FCM (g/L) | MED 95 (IQR 8.5) | Vitamin B12 deficiency | N° 24 (22.8%) |

| MCV (fL) | MED 78 (IQR 13) | Folate deficiency | N° 14 (13.3%) |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | MED 8 (IQR 11) | Hb disorders (total) | N° 18 (17.1%) |

| Transf Sat % | MED 10 (11 IQR) | B thalessemia Het | N° 13 (12.4%) |

| Iron μg/dL | MED 42 (IQR 58) | HbE | N° 3 (2.9%) |

| Hb after FCM (g/L) | MED 117 (IQR 1.5) | HbS | N° 2 (1.9%) |

| High CRP | N° 8 (7.6%) | Impaired EGFR | N° 3 (2.9%) |

| Hypophosphatemia | N° 6 (5.7%) |

| Parameter | Expected Values | Observed Values MED (IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Signal loss | <30% | 4% (9%) |

| Basal heart rate | 110–160 beats/min | 137 (10) beats/min |

| Heart rate accelerations > 10 beats/min | ≥1 episode | 3 (1.8) episodes |

| Heart rate accelerations > 20 beats/min | ≥1 episode | 3 (2.0) episodes |

| Heart rate decelerations > 10 beats/min | <2 episodes | 0 (1) episodes |

| Heart rate decelerations > 20 beats/min | <1 episode | 0 (0) episodes |

| Short-term variations | >4 ms | 12.9 (5.9) ms |

| High variability | ≥1 episode | 10 (4) episodes |

| Low variability | <1 in 50 min | 0 (0) episodes |

| Sinusoidal pattern | Absent | 0 (0) sinusoidal pattern |

| Fetal movements | Not Applicable | 5 (11) movements |

| Uterine contractions | Not Applicable | 2 (1) contractions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Polese, F.; Pesce, C.; De Fusco, G.; Tidore, G.; Coluccia, E.; Battista, R.; Gessoni, G. Fetal Safety of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose in Pregnancy: A Cardiotocography Study from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Italy. Hematol. Rep. 2026, 18, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010007

Polese F, Pesce C, De Fusco G, Tidore G, Coluccia E, Battista R, Gessoni G. Fetal Safety of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose in Pregnancy: A Cardiotocography Study from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Italy. Hematology Reports. 2026; 18(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010007

Chicago/Turabian StylePolese, Francesca, Chiara Pesce, Giulia De Fusco, Gianni Tidore, Enza Coluccia, Raffaele Battista, and Gianluca Gessoni. 2026. "Fetal Safety of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose in Pregnancy: A Cardiotocography Study from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Italy" Hematology Reports 18, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010007

APA StylePolese, F., Pesce, C., De Fusco, G., Tidore, G., Coluccia, E., Battista, R., & Gessoni, G. (2026). Fetal Safety of Intravenous Ferric Carboxymaltose in Pregnancy: A Cardiotocography Study from a Tertiary Care Hospital in Italy. Hematology Reports, 18(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010007