Iron Therapy in Pediatric Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Efficacy, Safety, and Formulation-Specific Trade-Offs—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Diagnosis

3.2. Neurodevelopment, Behaviour, and Growth

3.3. Therapeutic Goals, Dosing Strategies, and Pharmacological Considerations

3.3.1. Goals

3.3.2. Standard Pediatric Dosing

- Ferric complexes (iron polymaltose/iron polysaccharide): somewhat higher elemental Fe3+ iron (i.e., dose at 3–5 mg/kg/day in one or two doses with meals) because of lower bioavailability.

- Ferrous bisglycinate (FBC; amino-acid chelate): where used clinically, dosing generally aligns with 0.45 mg/kg/day, because of higher absorption [16].

- Vesicular/Encapsulated Liposomal/Sucrosomial Ferric Pyrophosphate: 1.4 mg/kg/day (cap around 29–30 mg/day) has been used in children [17].

3.3.3. Safety and Tolerability

3.3.4. Pitfalls

3.3.5. Daily vs. Alternate-Day

3.3.6. Oral Iron Pharmacology and Absorption: Why Dose, Timing, and Meals Matter

3.4. Monitoring

3.5. Prophylaxis Versus Therapeutic Supplementation

3.6. Oral Iron Formulation-Specific Evidence: Advantages and Drawbacks

3.6.1. Ferrous Salts (Sulfate, Fumarate, Gluconate)

Efficacy

Tolerability

Practical

3.6.2. Ferric Polymaltose/Iron Polymaltose Complex (IPC)

Efficacy

Tolerability

Practical

3.6.3. Amino-Acid Chelate: Ferrous Bisglycinate

Mechanism

Efficacy

Tolerability

Practical

3.6.4. Co-Processed Ferrous Bisglycinate with Sodium Alginate (Feralgine™; FBC-A)

Mechanism

Efficacy

Tolerability

Practical

3.6.5. Vesicular/Encapsulated Liposomal/Sucrosomial Ferric Pyrophosphate

Mechanism

Efficacy

Tolerability

Practical

3.6.6. Ferric Citrate Hydrate

Efficacy

Tolerability

3.7. Synoptical View

3.8. When (and Which) Intravenous Iron?

3.8.1. Indications

3.8.2. Agents

3.8.3. Dosages

3.8.4. Safety

3.8.5. Transfusion

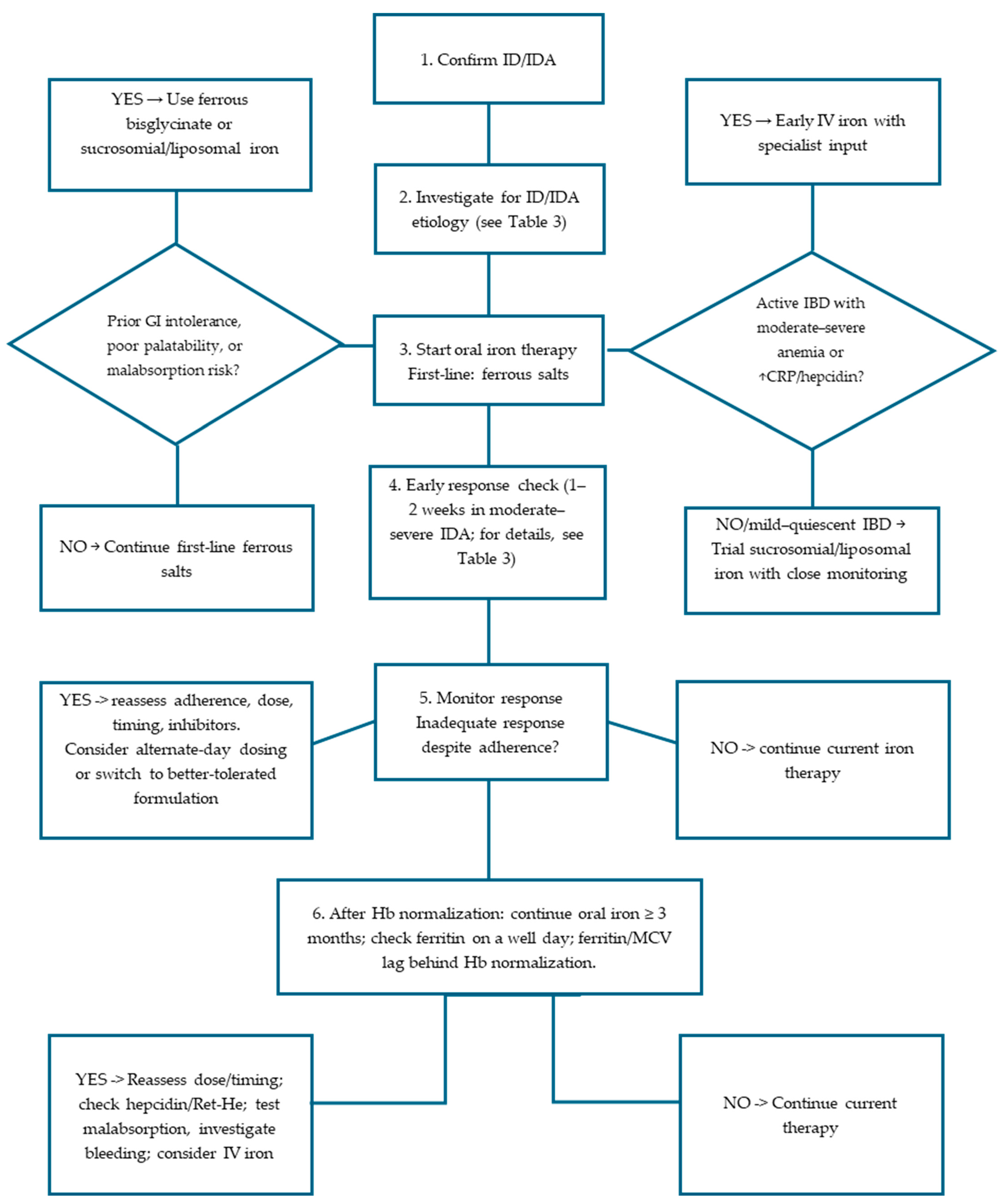

3.9. Practical Pediatric Algorithm (Figure 2, Table 3)

- 1

- Confirm ID/IDA with CBC, ferritin ± TSAT; consider Ret-He and sTfR if inflammation is present [2].

- 2

- If there are the following conditions:

- Age between 6 months and 2 years

- Prematurity

- Puberty

- Blood donors

- Pregnancy

- Gastro-intestinal diseases

- 3.

- Start oral ferrous salt (ferrous sulfate, fumarate, gluconate) at 2 mg/kg/day elemental iron for ID, once daily in the morning (preferred way); dosing of 2 mg/kg/day has been proposed for IDA as a still efficacious and better-tolerated schedule [15]. Provide clear adherence and diet counselling [2].

- Recommend lower elemental iron dosing, once-daily morning administration, away from meals; avoid tea/coffee/cocoa (inhibitors) around dosing; pair with modest vitamin C (fruit/juice) rather than very high pharmacologic doses. Provide age-tailored diet guidance (iron-rich foods, limit cow milk) [18].

- 4.

- Early check (1–2 weeks) in moderate–severe IDA to verify Hb trajectory and adherence; if Hb ↑ < 1 g/dL or intolerance:

- 5.

- Monitor during therapy to assess response and adherence; expect reticulocytosis by ~1 week, Hb rise by ~2–4 weeks [4,25]. If inadequate response and adherence is confirmed, reassess dose, formulation, administration timing, inhibitors, and consider hepcidin/Ret-He or inflammatory markers; in case of non-response after verified adherence, re-evaluate for malabsorption (celiac serology, Helicobacter pylori research in stool), and occult bleeding (including capsule endoscopy if indicated) [2,4,7,20]. consider IV iron [35,36].

- 6.

| Step | Key Action | Details/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Confirm ID/IDA | Diagnostic tests |

|

| 2. Investigate for ID/IDA etiology | If there are any of the following:

| Common etiologies:

|

| 3. Start oral iron therapy | First-line iron |

|

| Counselling |

| |

| If prior GI intolerance, poor palatability, or malabsorption risk |

| |

| If active IBD with moderate–severe anemia or ↑ CRP/hepcidin |

| |

| 4. Early response check | At 1–2 weeks in moderate–severe IDA | If Hb increase < 1 g/dL or intolerance:

|

| 5. Monitor therapy and evaluate non-response | Expected timeline |

|

| If poor response despite adherence |

| |

| 6. Continue treatment after Hb recovery | Iron store repletion |

|

3.10. Special Populations

3.10.1. Infants with Dietary Risks

3.10.2. Non-Anemic Iron Deficiency (NAID)

3.10.3. IBD/Celiac Disease/Malabsorption

3.10.4. Adolescents (e.g., Heavy Menstrual Bleeding)

3.10.5. Chronic Infections and Inflammatory States

3.11. Cost-Effectiveness and Health-System Considerations

3.12. Gaps and Future Directions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nutritional Anaemias: Tools for Effective Prevention and Control; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513067 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Iolascon, A.; Andolfo, I.; Russo, R.; Sanchez, M.; Busti, F.; Swinkels, D.; Aguilar Martinez, P.; Bou-Fakhredin, R.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Unal, S.; et al. Recommendations for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Hemasphere 2024, 8, e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Donker, A.E.; van der Staaij, H.; Swinkels, D.W. The critical roles of iron during the journey from fetus to adolescent: Developmental aspects of iron homeostasis. Blood Rev. 2021, 50, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscheo, C.; Licciardello, M.; Samperi, P.; La Spina, M.; Di Cataldo, A.; Russo, G. New Insights into Iron Deficiency Anemia in Children: A Practical Review. Metabolites 2022, 12, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mattiello, V.; Schmugge, M.; Hengartner, H.; von der Weid, N.; Renella, R.; SPOG Pediatric Hematology Working Group. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency in children with or without anemia: Consensus recommendations of the SPOG Pediatric Hematology Working Group. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2020, 179, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svenson, N.; Bailey, J.; Durairaj, S.; Dempsey-Hibbert, N. A simplified diagnostic pathway for the differential diagnosis of iron deficiency anaemia and anaemia of chronic disease. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 2021, 43, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camaschella, C. New insights into iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Blood Rev. 2017, 31, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, E.Y.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, S.K. Iron deficiency anemia in infants and toddlers. Blood Res. 2016, 51, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baker, R.D.; Greer, F.R.; Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics 2010, 126, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozoff, B.; Georgieff, M.K. Iron deficiency and brain development. Semin. Pediatr. Neurol. 2006, 13, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, A.; Cacoub, P.; Macdougall, I.C.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Iron deficiency anaemia. Lancet 2016, 387, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Song, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Yang, H.R. Serum hepcidin levels and iron parameters in children with iron deficiency. Korean J. Hematol. 2012, 47, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pasricha, S.R.; Hasan, M.I.; Braat, S.; Larson, L.M.; Tipu, S.M.M.; Hossain, S.J.; Shiraji, S.; Baldi, A.; Bhuiyan, M.S.A.; Tofail, F.; et al. Benefits and Risks of Iron Interventions in Infants in Rural Bangladesh. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 982–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahbah, W.A.; Omar, Z.A.; El-Shafie, A.M.; Mahrous, K.S.; El Zefzaf, H.M.S. Interventional impact of liposomal iron on iron-deficient children developmental outcome: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr. Res. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, E.; Giraudo, M.T.; Davitto, M.; Ansaldi, G.; Mondino, A.; Garbarini, L.; Franzil, A.; Mazzone, R.; Russo, G.; Ramenghi, U. Reticulocyte parameters: Markers of early response to oral treatment in children with severe iron-deficiency anemia. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2012, 34, e249–e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pineda, O.; Ashmead, H.D. Effectiveness of treatment of iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children with ferrous bis-glycinate chelate. Nutrition 2001, 17, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexiadou, S.; Tsigalou, C.; Kourkouni, E.; Tsalkidis, A.; Mantadakis, E. Oral Iron-Hydroxide Polymaltose Complex Versus Sucrosomial Iron for Children with Iron Deficiency with or without Anemia: A Clinical Trial with Emphasis on Intestinal Inflammation. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect Dis. 2024, 16, e2024075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cancelo-Hidalgo, M.J.; Castelo-Branco, C.; Palacios, S.; Haya-Palazuelos, J.; Ciria-Recasens, M.; Manasanch, J.; Pérez-Edo, L. Tolerability of different oral iron supplements: A systematic review. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2013, 29, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolkien, Z.; Stecher, L.; Mander, A.P.; Pereira, D.I.; Powell, J.J. Ferrous sulfate supplementation causes significant gastrointestinal side-effects in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zullo, A.; De Francesco, V.; Gatta, L.; Scaccianoce, G.; Colombo, M.; Bringiotti, R.; Azzarone, A.; Rago, A.; Corti, F.; Repici, A.; et al. Small bowel lesions in patients with iron deficiency anaemia without overt bleeding: A multicentre study. Ann. Hematol. 2024, 103, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niriella, M.A.; Jayasena, H.; Withanachchi, A.; Premawardhena, A. Mistakes in the management of iron deficiency anaemia: A narrative review. Hematology 2024, 29, 2387987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moretti, D.; Goede, J.S.; Zeder, C.; Jiskra, M.; Chatzinakou, V.; Tjalsma, H.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Brittenham, G.; Swinkels, D.W.; Zimmermann, M.B. Oral iron supplements increase hepcidin and decrease iron absorption from daily or twice-daily doses in iron-depleted young women. Blood 2015, 126, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, P.; Abhilasha, S. Efficacy of alternate day versus daily oral iron therapy in children with iron deficiency anemia: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Hematol. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Siebenthal, H.K.; Moretti, D.; Zimmermann, M.B.; Stoffel, N.U. Effect of dietary factors and time of day on iron absorption from oral iron supplements in iron deficient women. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, G.; Guardabasso, V.; Romano, F.; Corti, P.; Samperi, P.; Condorelli, A.; Sainati, L.; Maruzzi, M.; Facchini, E.; Fasoli, S.; et al. Monitoring oral iron therapy in children with iron deficiency anemia: An observational, prospective, multicenter study of AIEOP patients (Associazione Italiana Emato-Oncologia Pediatrica). Ann. Hematol. 2020, 99, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkin, P.C.; Borkhoff, C.M.; Macarthur, C.; Abdullah, K.; Birken, C.S.; Fehlings, D.; Koroshegyi, C.; Maguire, J.L.; Mamak, E.; Mamdani, M.; et al. Randomized Trial of Oral Iron and Diet Advice versus Diet Advice Alone in Young Children with Nonanemic Iron Deficiency. J. Pediatr. 2021, 233, 233–240.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiliç, B.O.; Konuksever, D.; Özbek, N.Y. Comparative Efficacy of Ferrous, Ferric and Liposomal Iron Preparations for Prophylaxis in Infants. Indian Pediatr. 2024, 61, 621–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Rosli, R.R.; Norhayati, M.N.; Ismail, S.B. Effectiveness of iron polymaltose complex in treatment and prevention of iron deficiency anemia in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chandra, J.; Sangeeta. Iron Supplementation in Infancy: Which Preparation and at What age to Begin? Indian Pediatr. 2024, 61, 616–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppsen, R.B.; Borzelleca, J.F. Safety evaluation of ferrous bisglycinate chelate. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1999, 37, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talarico, V.; Giancotti, L.; Mazza, G.A.; Marrazzo, S.; Miniero, R.; Bertini, M. FERALGINE™ a New Oral Iron Compound. In Iron Metabolism: A Double-Edged Sword; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momoeda, M.; Ito, K.; Inoue, S.; Shibahara, H.; Mitobe, Y.; Komatsu, N. Cost-effectiveness of ferric citrate hydrate in patients with iron deficiency anemia. Int. J. Hematol. 2025, 121, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giordano, G.; Napolitano, M.; Di Battista, V.; Lucchesi, A. Oral high-dose sucrosomial iron vs. intravenous iron in sideropenic anemia patients intolerant/refractory to iron sulfate: A multicentric randomized study. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pisani, A.; Riccio, E.; Sabbatini, M.; Andreucci, M.; Del Rio, A.; Visciano, B. Effect of oral liposomal iron versus intravenous iron for treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in CKD patients: A randomized trial. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2015, 30, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, M.; Ballard, H. Clinical use of intravenous iron: Administration, efficacy, and safety. Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2010, 2010, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantadakis, E. Parenteral iron therapy in children with iron deficiency anemia. World J. Pediatr. 2016, 12, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dignass, A.U.; Gasche, C.; Bettenworth, D.; Birgegård, G.; Danese, S.; Gisbert, J.P.; Gomollon, F.; Iqbal, T.; Katsanos, K.; Koutroubakis, I.; et al. European consensus on the diagnosis and management of iron deficiency and anaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2015, 9, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Iron Formulation | Recommended Dosage | Advantages | Drawbacks | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrous salts | 2–6 mg/kg/day in 1–3 doses | Standard treatment Good absorption Low cost | Frequent gastro-intestinal side effects Metallic taste Dental staining Stool discoloration | Dosage of 2 mg/kg/day has been proposed as still being an efficacious and better-tolerated schedule; prefer once-daily morning dose; alternate-day dosing is supported by a recent RCT [23]. |

| Ferric polymaltose/Iron polymaltose complex | 3–5 mg/kg/day in 1–2 doses | Better gastro-intestinal tolerability than ferrous salts | Less effective than ferrous salts | |

| Ferrous bysglicinate | 0.45 mg/kg/day in 1–2 doses | Good intestinal absorption Limited side effects | Higher cost than ferrous salts | |

| Liposomal/sucrosomial ferric pyrophosphate | 1.4 mg/kg/day in 1–2 doses | Excellent palatability Limited side effects | Possible less prompt response to therapy Less effective in prophylaxis than ferrous salts Higher cost than ferrous salts | Sparse prophylaxis data on tolerability |

| Iron Formulation | Recommended Dosage | Advantages | Drawbacks | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron sucrose | 5 mg/kg/dose, on alternate days, up to 3×/week (until iron deficit is replaced); single-day dose ≤ 300 mg, infused ≥ 90 min | Hospitalization required Multiple infusions | ||

| Ferric gluconate | Total dose to be calculated based on initial Hb and weight | Effectiveness independent of gastro-intestinal absorption Very low gastro-enteric side effects | Hospitalization required Multiple infusions | |

| Ferric carboxymaltose (FCM) | 15 mg/kg per infusion (up to 750 mg) on day 0 and day 7 (total 1500 mg) in children ≥ 1 year | Effectiveness independent of gastro-intestinal absorption Once-weekly administration | Hospitalization required Higher risk of hypophosphatemia compared to other formulations | Phase-2 pediatric data explored 7.5 mg/kg per infusion dosing |

| Iron isomaltoside/Ferric derisomaltose (IIM) | 10–20 mg/kg (max 1000 mg) in children < 18 years | Effectiveness independent of gastro-intestinal absorption Single administration | Hospitalization required |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leone, G.; Arrabito, M.; Russo, G.; La Spina, M. Iron Therapy in Pediatric Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Efficacy, Safety, and Formulation-Specific Trade-Offs—A Narrative Review. Hematol. Rep. 2026, 18, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010006

Leone G, Arrabito M, Russo G, La Spina M. Iron Therapy in Pediatric Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Efficacy, Safety, and Formulation-Specific Trade-Offs—A Narrative Review. Hematology Reports. 2026; 18(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeone, Guido, Marta Arrabito, Giovanna Russo, and Milena La Spina. 2026. "Iron Therapy in Pediatric Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Efficacy, Safety, and Formulation-Specific Trade-Offs—A Narrative Review" Hematology Reports 18, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010006

APA StyleLeone, G., Arrabito, M., Russo, G., & La Spina, M. (2026). Iron Therapy in Pediatric Iron Deficiency and Iron-Deficiency Anemia: Efficacy, Safety, and Formulation-Specific Trade-Offs—A Narrative Review. Hematology Reports, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep18010006