Racial Inequities Influencing Admission, Disposition and Hospital Outcomes for Sickle Cell Anemia Patients: Insights from the National Inpatient Sample Database

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Database—The National Inpatient Sample 2016–2020

2.2. Study Population and Study Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient- and Hospital-Level Characteristics

3.2. Primary Outcomes

3.3. In-Hospital Complications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SCD | Sickle Cell Disease |

| NIS | National Inpatient Sample |

| AOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| HCUP | Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project |

| ICD-10 | International Classification of Disease-Tenth Edition-Clinical Modification |

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| DVT | Deep Vein Thrombosis |

| PHTN | Pulmonary Hypertension |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| RBCs | Red Blood Cells |

References

- Ehsan, M.; Maruvada, S. Sickle Cell Anemia. Nih.gov. StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482164/ (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Naoum, P.C. Sickle cell disease. Rev. Bras. Hematol. Hemoter. 2011, 33, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Sickle Cell Disease—What Is Sickle Cell Disease? 2023. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sickle-cell-disease (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Therrell, B.L.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.A.; Eckman, J.R.; Mann, M.Y. Newborn screening for sickle cell diseases in the United States: A review of data spanning 2 decades. Semin. Perinatol. 2015, 39, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, A.; Cong, Z.; Agodoa, I.; Song, X.; Martinez, D.J.; Black, D.; Lew, C.R.; Varker, H.; Chan, C.; Lanzkron, S. The Economic Burden of End-Organ Damage Among Medicaid Patients with Sickle Cell Disease in the United States: A Population-Based Longitudinal Claims Study. J. Manag. Care Spec. Pharm. 2020, 26, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraf, S.L.; Molokie, R.E.; Nouraie, M.; Sable, C.A.; Luchtman-Jones, L.; Ensing, G.J.; Campbell, A.D.; Rana, S.R.; Niu, X.M.; Machado, R.F.; et al. Differences in the clinical and genotypic presentation of sickle cell disease around the world. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2014, 15, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenton, J.J.; Jerant, A.F.; Franks, P. Influence of Elective versus Emergent Hospital Admission on Patient Satisfaction. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2014, 27, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundararajan, V.; Henderson, T.; Perry, C.; Muggivan, A.; Quan, H.; Ghali, W.A. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2004, 57, 1288–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, A.; Olayemi, A.; Ogbonda, S.; Nair, K.; Wang, J.C. Racial and ethnic differences in sickle cell disease within the United States: From demographics to outcomes. Eur. J. Haematol. 2023, 110, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzkron, S.; Carroll, C.P.; Haywood, C., Jr. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979–2005. Public Health Rep. 2013, 128, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiao, B.; Johnson, K.M.; Ramsey, S.D.; Bender, M.A.; Devine, B.; Basu, A. Long-Term Survival with Sickle Cell Disease: A Nationwide Cohort Study of Medicare and Medicaid Beneficiaries. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 3276–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, H.; Perraillon, M.C.; Werner, R.M.; Grabowski, D.C.; Konetzka, R.T. Medicaid and Nursing Home Choice: Why Do Duals End Up in Low-Quality Facilities? J. Appl. Gerontol. 2019, 39, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukamel, D.B.; Ladd, H.; Li, Y.; Temkin-Greener, H.; Ngo-Metzger, Q. Have Racial Disparities in Ambulatory Care Sensitive Admissions Abated over Time? Med. Care 2015, 53, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haywood, C.; Tanabe, P.; Naik, R.; Beach, M.C.; Lanzkron, S. The impact of race and disease on sickle cell patient wait times in the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2013, 31, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haywood, C.; Diener-West, M.; Strouse, J.; Carroll, C.P.; Bediako, S.; Lanzkron, S.; Haythornthwaite, J.; Onojobi, G.; Beach, M.C.; Woodson, T.; et al. Perceived Discrimination in Health Care Is Associated with a Greater Burden of Pain in Sickle Cell Disease. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 934–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medrek, S.K.; Sahay, S. Ethnicity in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Chest 2018, 153, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Acker, J.P. Immunological impact of the CD71+ RBCs: A potential immune mediator in transfusion. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2023, 62, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | White [22,710] (%) | African American [981,759] (%) | Hispanic [52,176] (%) | Others [32,569] (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||

| Less than 65 years | 63.78 | 82.93 | 87.72 | 85.06 | <0.001 |

| Greater than 65 years | 36.22 | 17.07 | 12.28 | 14.94 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 33.02 | 35.15 | 29.18 | 30.85 | <0.001 |

| Female | 66.98 | 64.85 | 70.82 | 69.15 | |

| Median household income national quartiles | |||||

| Quartile 1 (0–25th percentile) | 31.58 | 51.74 | 45.91 | 37.91 | <0.001 |

| Quartile 2 (26–50th percentile) | 24.37 | 22.41 | 23.45 | 20.84 | |

| Quartile 3 (51–75th percentile) | 23.51 | 16.1 | 18.7 | 20.79 | |

| Quartile 4 (76–100th percentile) | 20.54 | 9.75 | 11.94 | 20.46 | |

| Insurance Type | |||||

| Medicare | 31.24 | 29.11 | 17.3 | 16.98 | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 28.75 | 44.75 | 53.21 | 45.74 | |

| Private | 33.14 | 19.88 | 21.66 | 29.5 | |

| Other | 6.88 | 6.27 | 7.83 | 7.77 | |

| Hospital Region | |||||

| Northeast | 23.15 | 18.54 | 45.73 | 45.36 | <0.001 |

| Midwest | 18.34 | 19.92 | 4.8 | 9.02 | |

| South | 42.63 | 53.39 | 38.34 | 36.05 | |

| West | 15.89 | 8.15 | 11.12 | 9.17 | |

| Hospital Location | |||||

| Rural | 3.8 | 3.67 | 1.13 | 2.33 | <0.001 |

| Urban non-teaching | 19.93 | 14.04 | 12.33 | 11.49 | |

| Urban teaching | 76.27 | 82.29 | 86.55 | 85.17 | |

| Hospital bed size | |||||

| Small | 20.04 | 16.35 | 16.14 | 14.27 | 0.1864 |

| Medium | 25.37 | 26.75 | 27.49 | 26.84 | |

| Large | 54.58 | 56.89 | 56.37 | 58.89 | |

| Outcomes | White [22,710] (%) | African American [981,759] (%) | Hispanic [52,176] (%) | Others [32,569] (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient disposition | |||||

| Routine | 78.11 | 88.11 | 89.21 | 87.16 | <0.001 |

| Transfer to facility/home healthcare | 21.09 | 11.24 | 9.97 | 12.3 | |

| Died | 0.8 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.54 | |

| Admission Type | |||||

| Non-Elective | 77.81 | 87.7 | 83.3 | 81.74 | <0.001 |

| Elective | 22.19 | 12.3 | 16.7 | 18.26 | |

| Length of stay | |||||

| Less than 7 days | 80.13 | 78.09 | 81.16 | 78.8 | <0.001 |

| More than 7 days | 19.87 | 21.91 | 18.84 | 21.2 | |

| Elective vs. Non-Elective Admission AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Facility/Home Health vs. Routine AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Died vs. Routine AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Length of Stay > 7 Days AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White [22,710] | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| African American [981,759] | 0.5 (0.45–0.56, <0.001) | 0.88 (0.69–1.14, 0.352) | 1.53 (0.61–3.85, 0.362) | 1.3 (1.17–1.42, <0.001) |

| Hispanic [52,176] | 0.75 (0.65–0.84, <0.001) | 0.79 (0.57–1.09, 0.159) | 2.29 (0.71–7.37, 0.165) | 1.06 (0.94–1.2, 0.289) |

| Other [32,569] | 0.8 (0.69–0.93, 0.003) | 0.86 (0.61–1.2, 0.387) | 1.35 (0.37–4.95, 0.648) | 1.2 (1.05–1.37, 0.006) |

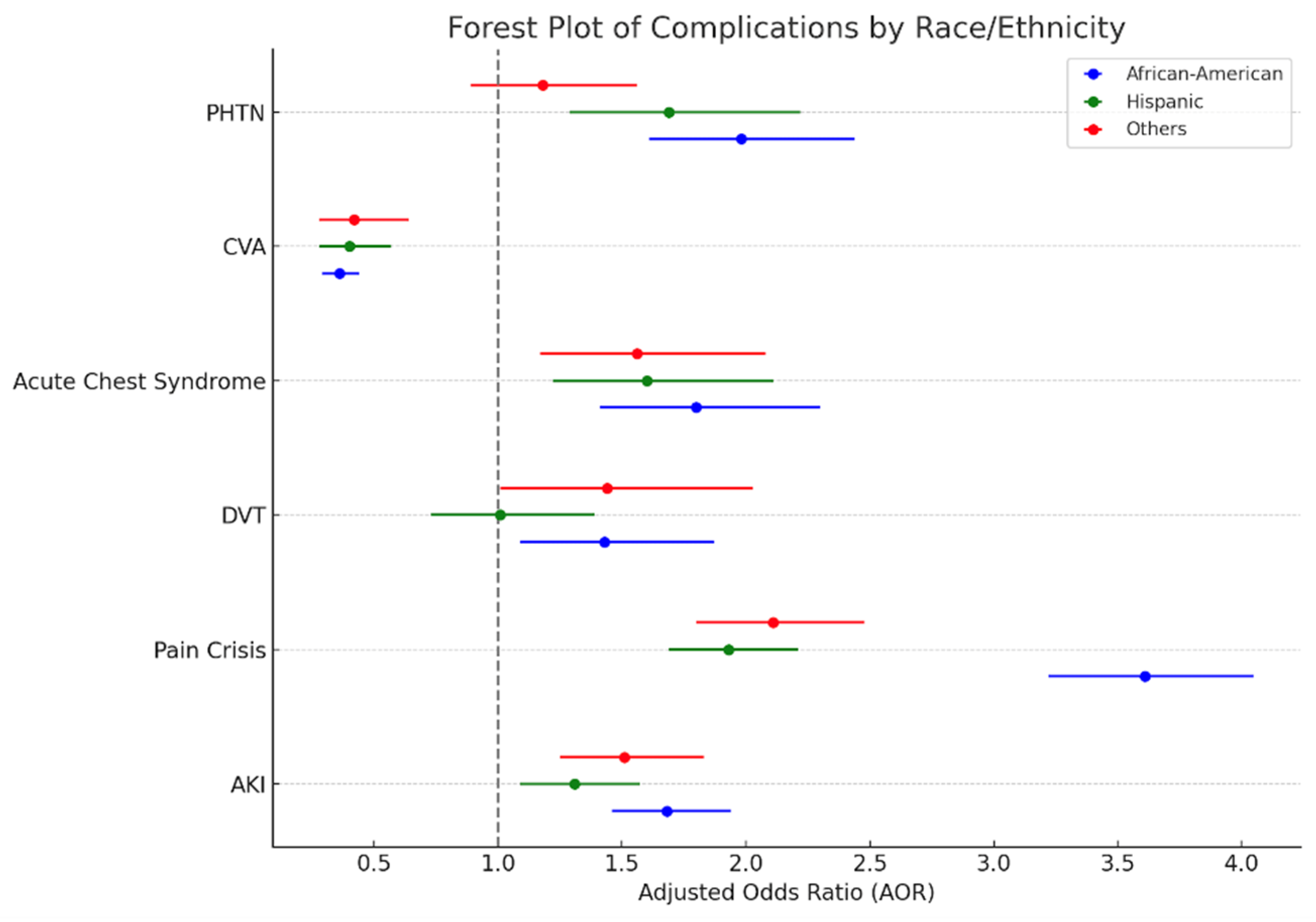

| Complications | White [22,710] | African American [981,759] AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Hispanic [52,176] AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] | Others [32,569] AOR * [95% CI, p-Value] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI | Reference | 1.68 (1.46–1.94, 0.001) | 1.31 (1.09–1.57, 0.003) | 1.51 (1.25–1.83, 0.001) |

| Pain Crisis | Reference | 3.61 (3.22–4.05, 0.001) | 1.93 (1.69–2.21, 0.001) | 2.11 (1.8–2.48, 0.001) |

| DVT | Reference | 1.43 (1.09–1.87, 0.011) | 1.01 (0.73–1.39, 0.949) | 1.44 (1.01–2.03, 0.041) |

| Acute Chest Syndrome | Reference | 1.8 (1.41–2.3, 0.001) | 1.6 (1.22–2.11, 0.001) | 1.56 (1.17–2.08, 0.002) |

| CVA | Reference | 0.36 (0.29–0.44, 0.001) | 0.4 (0.28–0.57, 0.001) | 0.42 (0.28–0.64, 0.001) |

| PHTN | Reference | 1.98 (1.61–2.44, 0.001) | 1.69 (1.29–2.22, 0.001) | 1.18 (0.89–1.56, 0.241) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jayakumar, J.; Vojjala, N.; Ginjupalli, M.; Khan, F.; Ayyazuddin, M.; Turku, D.; Babu, K.; Rajarajan, S.; Bhanushali, C.; Mathew, T.A.; et al. Racial Inequities Influencing Admission, Disposition and Hospital Outcomes for Sickle Cell Anemia Patients: Insights from the National Inpatient Sample Database. Hematol. Rep. 2025, 17, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17030027

Jayakumar J, Vojjala N, Ginjupalli M, Khan F, Ayyazuddin M, Turku D, Babu K, Rajarajan S, Bhanushali C, Mathew TA, et al. Racial Inequities Influencing Admission, Disposition and Hospital Outcomes for Sickle Cell Anemia Patients: Insights from the National Inpatient Sample Database. Hematology Reports. 2025; 17(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleJayakumar, Jayalekshmi, Nikhil Vojjala, Manasa Ginjupalli, Fiqe Khan, Meher Ayyazuddin, Davin Turku, Kalaivani Babu, Srinishant Rajarajan, Charmi Bhanushali, Tijin Ann Mathew, and et al. 2025. "Racial Inequities Influencing Admission, Disposition and Hospital Outcomes for Sickle Cell Anemia Patients: Insights from the National Inpatient Sample Database" Hematology Reports 17, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17030027

APA StyleJayakumar, J., Vojjala, N., Ginjupalli, M., Khan, F., Ayyazuddin, M., Turku, D., Babu, K., Rajarajan, S., Bhanushali, C., Mathew, T. A., Ramadas, P., & Krishnamoorty, G. (2025). Racial Inequities Influencing Admission, Disposition and Hospital Outcomes for Sickle Cell Anemia Patients: Insights from the National Inpatient Sample Database. Hematology Reports, 17(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/hematolrep17030027