Effects of Magnesium Sulphate Fertilization on Glucosinolate Accumulation in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review Methodology

3. History of Watercress

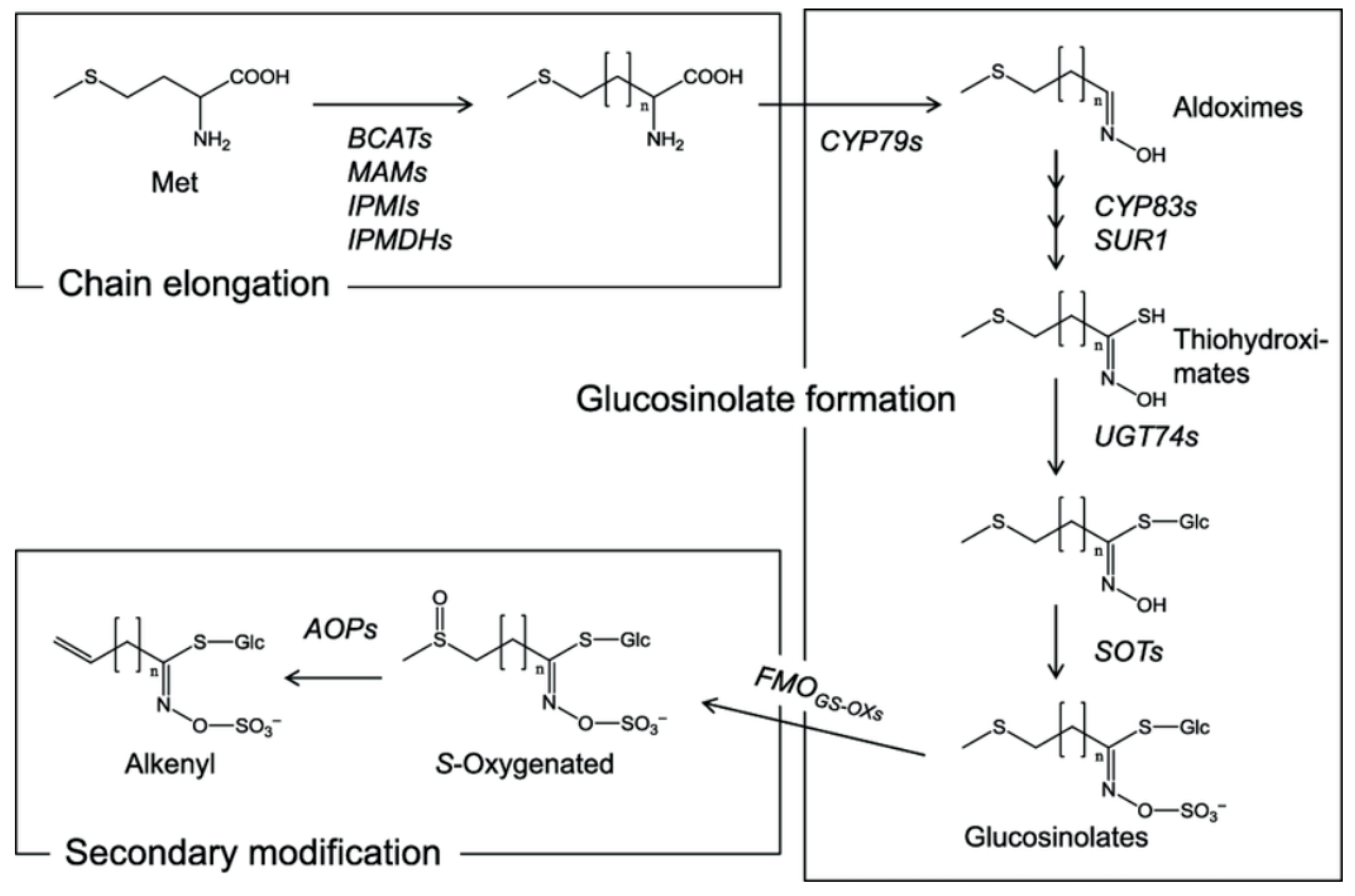

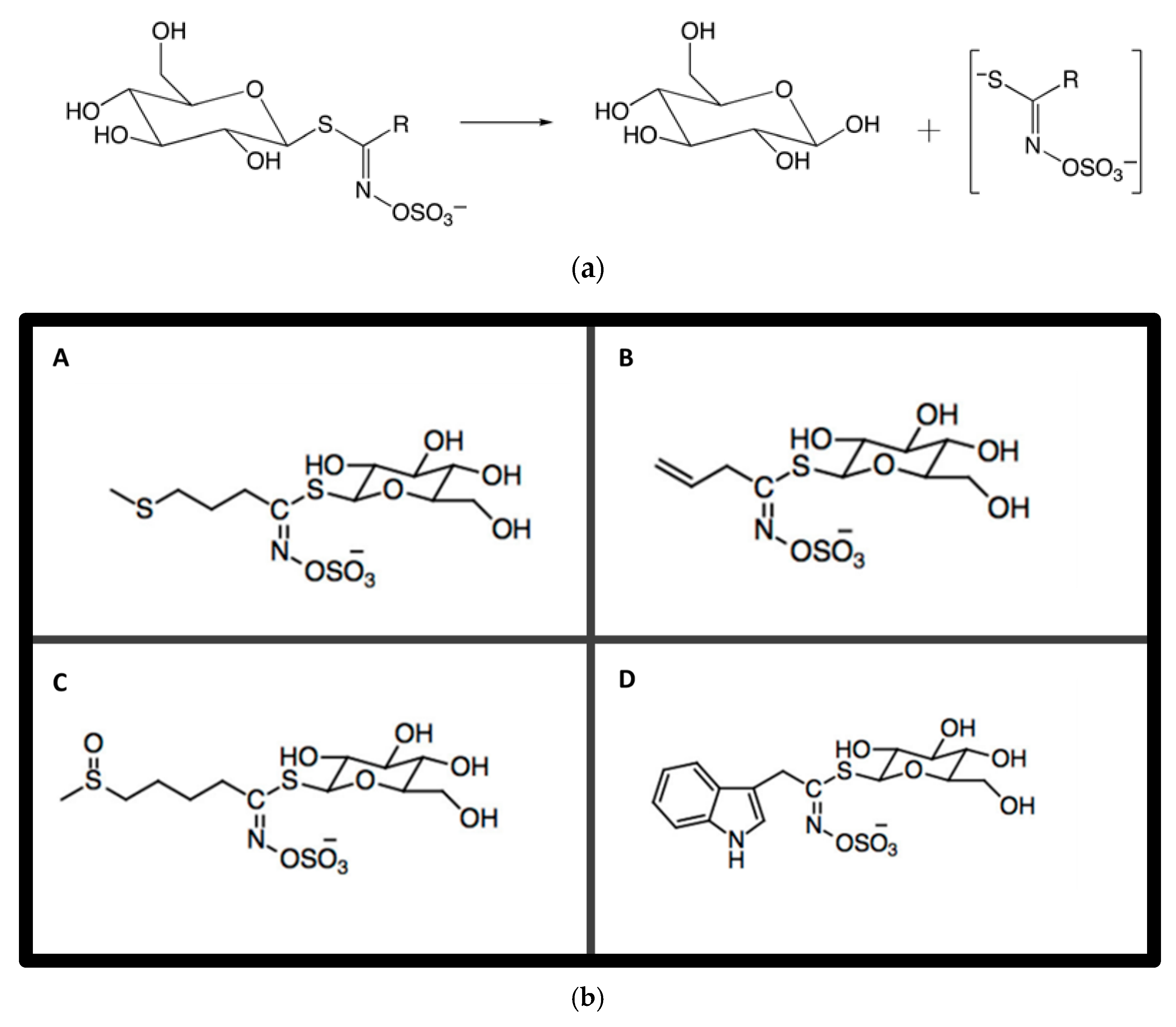

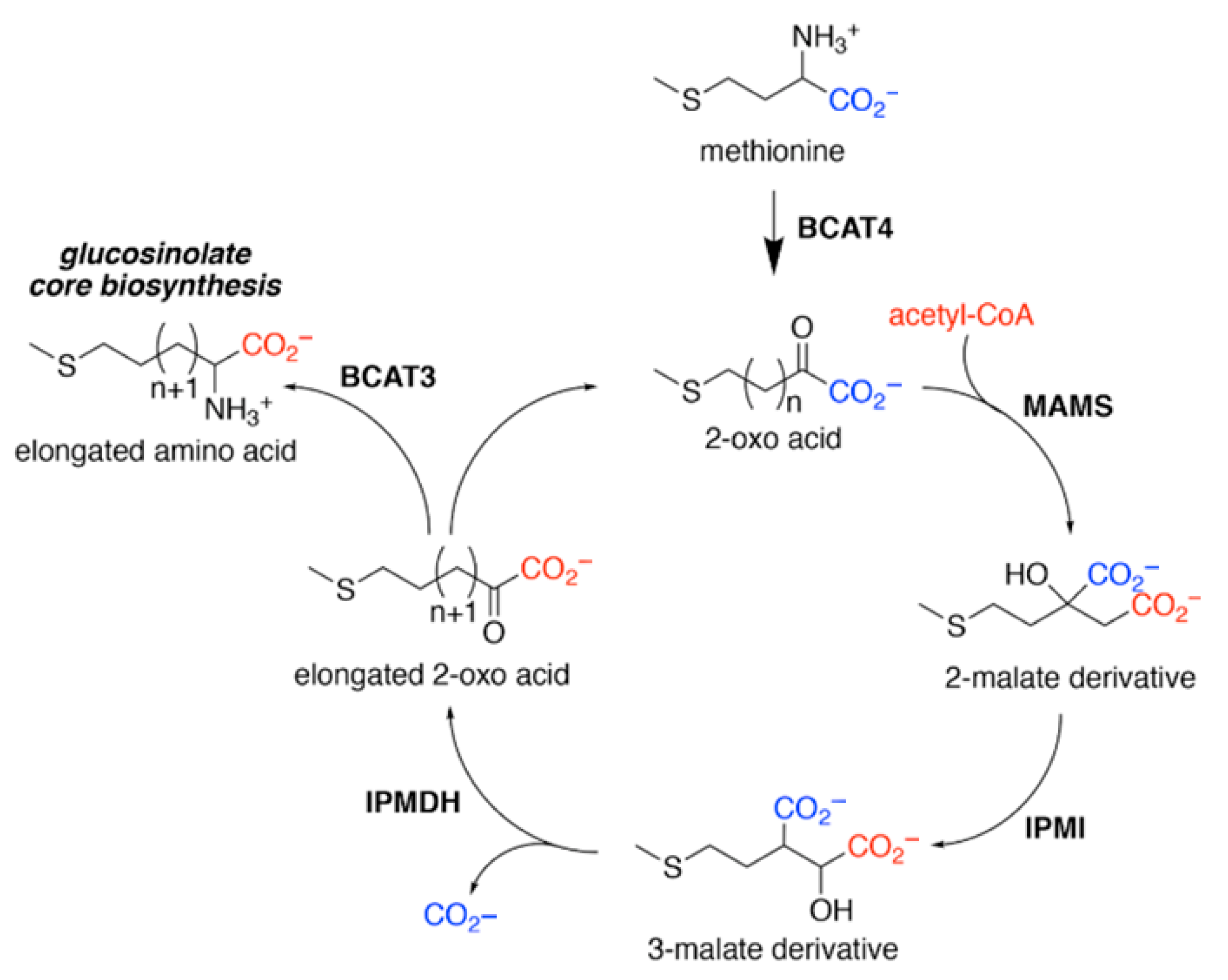

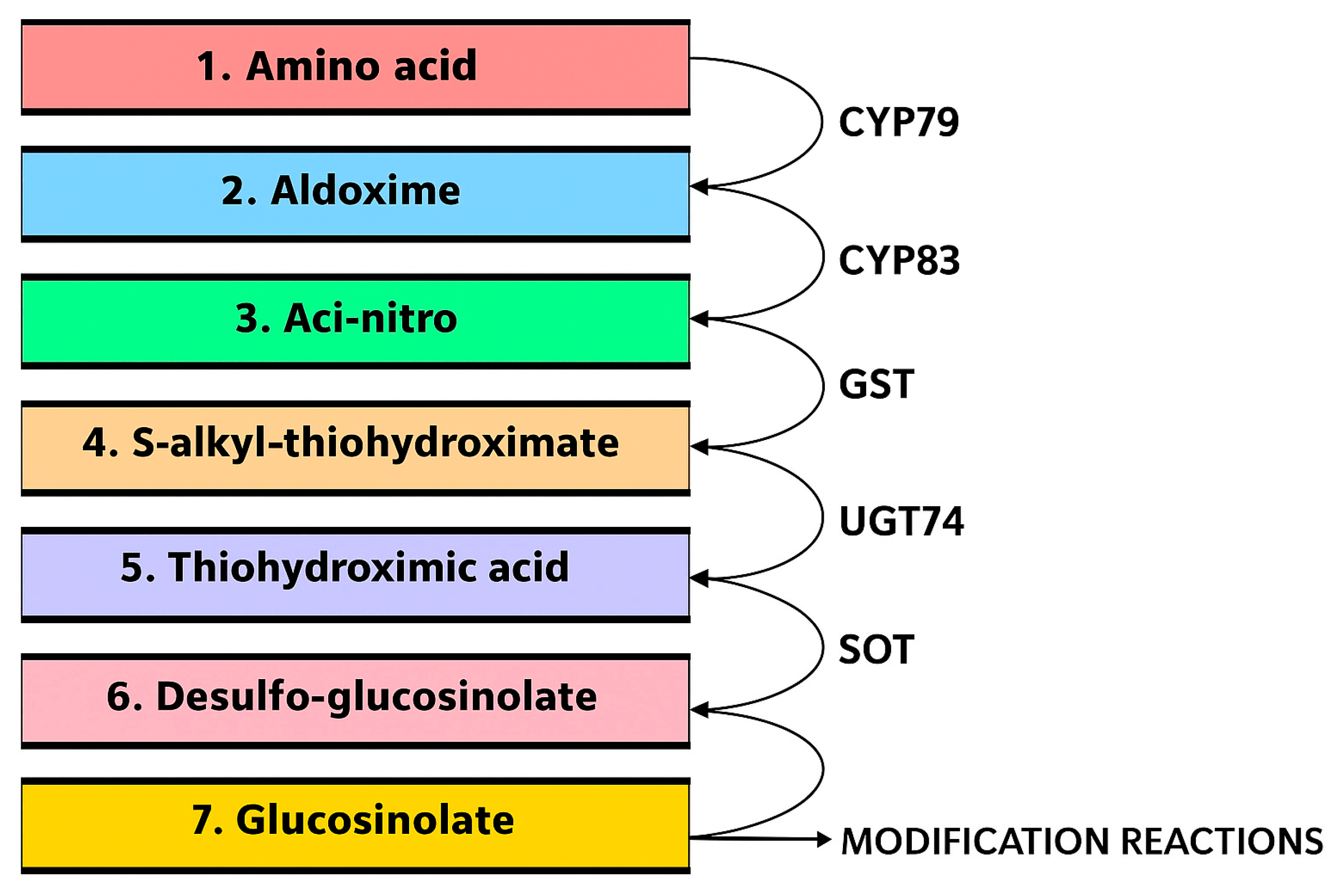

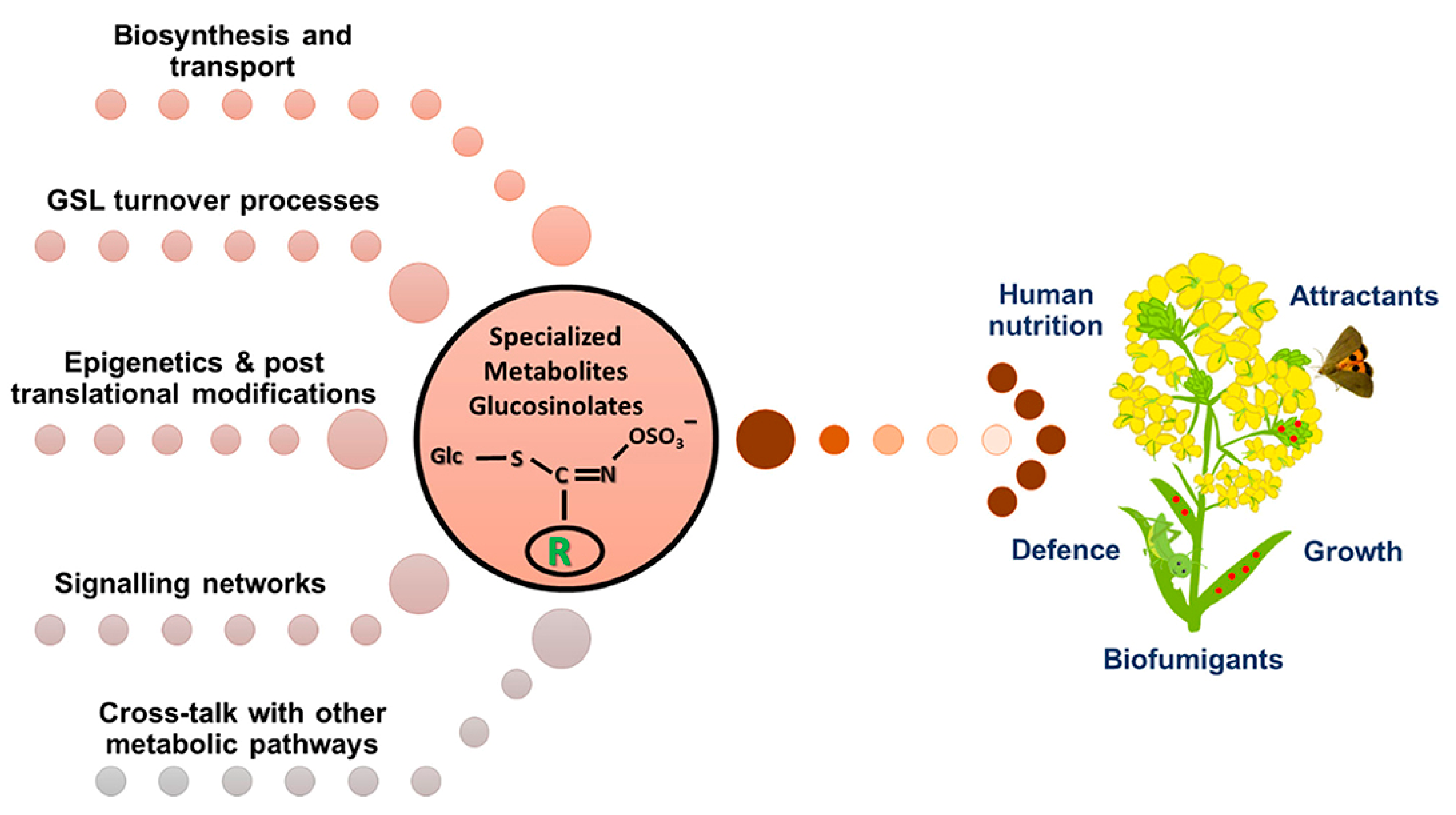

4. The Science Behind Glucosinolates

5. Glucosinolates in Agriculture

6. Glucosinolates in the Human Diet

7. Pharmacological Potential of Watercress

8. Literature Gaps Relevant to Glucosinolates in Watercress

8.1. Glucosinolate Accumulation Under Soilless Conditions

8.2. Impact of Magnesium Sulphate on Glucosinolate Accumulation

8.3. Impact of Magnesium Sulphate on Glucosinate Accumulation in Hydroponically Grown Watercress

9. Factors Influencing Glucosinolate Biosynthesis and Accumulation

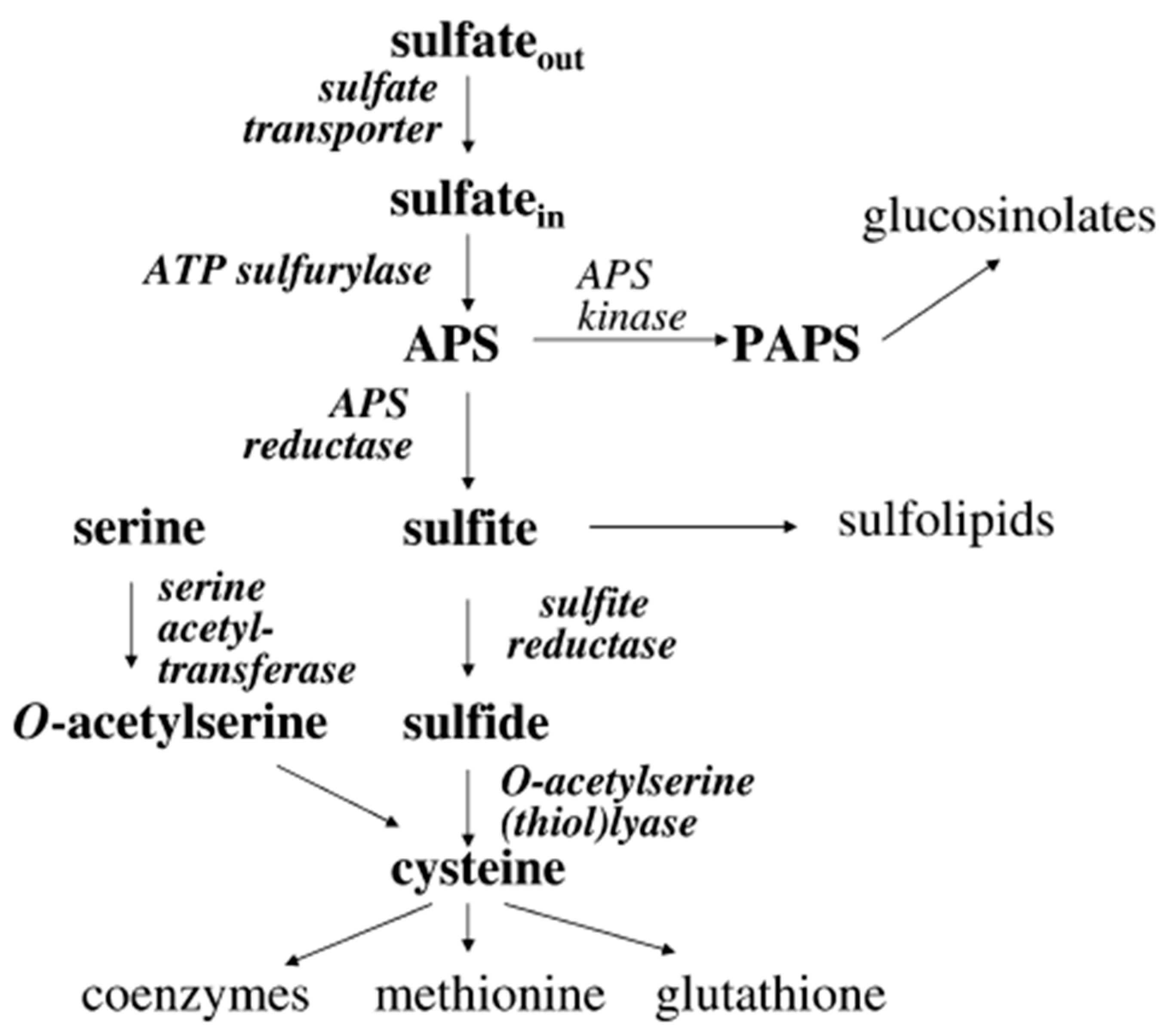

9.1. Effect of Sulphur Fertilization on the Glucosinolate Content

9.2. Effect of Magnesium on Glucosinate Content

9.3. Environmental Factors Affecting Glucosinolate Biosynthesis

9.4. Transcriptomic, Epigenetic and Metabolomic Factors Affecting Glucosinolate Biosynthesis

9.5. Intra-Genic Variation in Glucosinolate Biosynthesis

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSLs | Glucosinolates |

| MAM | Methylthioalkylmalate synthase |

| PAPS | 3′-phosphoadenylyl sulphate |

References

- Balliu, A.; Zheng, Y.; Sallaku, G.; Fernández, J.A.; Gruda, N.S.; Tuzel, Y. Environmental and cultivation factors affect the morphology, architecture and performance of root systems in soilless grown plants. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, K.L.; Tokuhisa, J.G.; Gershenzon, J. The Effect of Sulfur Nutrition on Plant Glucosinolate Content: Physiology and Molecular Mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2007, 9, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenda, T.; Liu, S.; Dong, A.; Duan, H. Revisiting sulphur—The once neglected nutrient: It’s roles in plant growth, metabolism, stress tolerance and crop production. Agriculture 2021, 11, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Zeng, F.; Graciano, C.; Ullah, A.; Sadia, S.; Ahmed, Z.; Murtaza, G.; Ismoilov, K.; Zhang, Z. Regulation of Metabolites by Nutrients in Plants. In Plant Ionomics, Sensing, Signaling, and Regulation; Singh, V.P., Siddiqui, M.H., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bok, G.; Choi, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.; Park, J. Microbubbles increase glucosinolate contents of watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.) grown in hydroponic cultivation. J. Bio-Environ. Control 2019, 28, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.; Amayreh, M.; Sanduka, S.; Salah, Z.; Al-Rimawi, F.; Al-Mazaideh, G.M.; Alanezi, A.A.; Wedian, F.; Alasmari, F.; Shalayel, M.H.F. Assessment of antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities of Sisymbrium officinale plant extract. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, A.A.; Hassanin, S.O.; Hamza, S.; Abdalla, A.; Amin, A. Polyphenolic-enriched olive leaf extract attenuated doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats via suppression of oxidative stress and inflammation. J. Basic Appl. Zool. 2021, 82, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, R.; Zahoor, M.; Shah, A.B.; Majid, F. Determination of antioxidants and antibacterial activities, total phenolic, polyphenol and pigment contents in Nasturtium officinale. Pharmacologyonline 2017, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri, H. Volatile constituents and antioxidant activity of flowers, stems and leaves of Nasturtium officinale R. Br. Nat. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluwa, C.; Zinan’dala, B.; Chuljerm, H.; Parklak, W.; Kulprachakarn, K. Watercress (Nasturtium officinale) as a Functional Food for Non-Communicable Diseases Prevention and Management: A Narrative Review. Life 2025, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilash, A.B.; Jahanbani, J.; Jolehar, M. Effect of nasturtium extract on oral cancer. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2023, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voutsina, N.; Hancock, R.D.; Becerra-Sanchez, F.; Qian, Y.; Taylor, G. Characterization of a new dwarf watercress (Nasturtium officinale R Br.) ‘Boldrewood’ in commercial trials reveals a consistent increase in chemopreventive properties in a longer-grown crop. Euphytica 2024, 220, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Jin, L.; Lin, S. Anticarcinogenic effects of isothiocyanates on hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Hisham, H.; Mohamed, D. A review on phytochemical and pharmacological potential of watercress plant. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, S.; Michailidou, K.; Amery, T.; Stewart, K.; Winyard, P.G.; Trafalis, D.T.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Polyphenolics, glucosinolates and isothiocyanates profiling of aerial parts of Nasturtium officinale (Watercress). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek-Szczykutowicz, M.; Szopa, A.; Ekiert, H. Chemical composition, traditional and professional use in medicine, application in environmental protection, position in food and cosmetics industries, and biotechnological studies of Nasturtium officinale (watercress)—A review. Fitoterapia 2018, 129, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Bhat, S.A.; Narayan, S. Wild edible plants as a food Resource: Traditional Knowledge. Preprint 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; Di Gioia, F.; Leoni, B.; Mininni, C.; Santamaria, P. Culinary Assessment of Self-Produced Microgreens as Basic Ingredients in Sweet and Savory Dishes. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2017, 15, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakou, S.; Potamiti, L.; Demosthenous, N.; Amery, T.; Stewart, K.; Winyard, P.G.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. A naturally derived watercress flower-based phenethyl isothiocyanate-enriched extract induces the activation of intrinsic apoptosis via subcellular ultrastructural and Ca2+ efflux alterations in an in vitro model of human malignant melanoma. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijkuokool, P.; Stepanov, I.; Ounjaijean, S.; Koonyosying, P.; Rerkasem, K.; Chuljerm, H.; Parklak, W.; Kulprachakarn, K. Effects of Drying Methods on the Phytochemical Contents, Antioxidant Properties, and Anti-Diabetic Activity of Nasturtium officinale R. Br. (Betong Watercress) from Southern Thailand. Life 2024, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstock, U.; Burow, M. Glucosinolate breakdown in Arabidopsis: Mechanism, regulation and biological significance. Arab. Book 2010, 8, E0134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noia, J. Defining powerhouse fruits and vegetables: A nutrient density approach. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, E95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, C.D.; Abel, S. Glucosinolate metabolism and its control. Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graser, G.; Oldham, N.J.; Brown, P.D.; Temp, U.; Gershenzon, J. The biosynthesis of benzoic acid glucosinolate esters in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food Balance Sheet 2002; Food and Agriculture Organization of United Nation: Rome, Italy, 2005; Available online: http://faostat.fao.org/faostat (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- NASS. Quick Stats. 2023. Available online: https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/ (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- Howard, H.W.; Lyon, A.G. Nasturtium officinale R. Br. (Rorippa Nasturtium-Aquaticum (L.) Hayek). J. Ecol. 1952, 40, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, M.; Miguel, M.; Gribner, C.; Moura, P.F.; Angelica, A.; Rigoni, R.; Fernandes, L.C.; Miguel, O.G. Watercress, as a functional food, with protective effects on human health against oxidative stress: A review study. Int. J. Med. Plants Nat. Prod. 2019, 5, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, B.A.; Gershenzon, J. Biology and Biochemistry of Glucosinolates. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006, 57, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, S.; Abdullah-Zawawi, M.R.; Goh, H.H.; Mohamed-Hussein, Z.A. A Comprehensive Gene Inventory for Glucosinolate Biosynthetic Pathway in Arabidopsis thali-ana. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 7281–7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigolashvili, T.; Yatusevich, R.; Rollwitz, I.; Humphry, M.; Gershenzon, J.; Flügge, U.I. The plastidic bile acid transporter 5 is required for the biosynthesis of methionine-derived glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 1813–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Textor, S.; De Kraker, J.W.; Hause, B.; Gershenzon, J.; Tokuhisa, J.G. MAM3 catalyzes the formation of all aliphatic glucosinolate chain lengths in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, A.; Hansen, L.G.; Mirza, N.; Crocoll, C.; Mirza, O.; Halkier, B.A. Changing substrate specificity and iteration of amino acid chain elongation in glucosinolate biosynthesis through targeted mutagenesis of Arabidopsis methylthioalkylmalate synthase 1. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, BSR20190446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Chen, B.; Pang, Q.; Strul, J.M.; Chen, S. Functional specification of Arabidopsis isopropylmalate isomerases in glucosinolate and leucine biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knill, T.; Reichelt, M.; Paetz, C.; Gershenzon, J.; Binder, S. Arabidopsis thaliana encodes a bacterial-type heterodimeric isopropylmalate isomerase involved in both Leu biosynthesis and the Met chain elongation pathway of glucosinolate formation. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 71, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravilious, G.E.; Jez, J.M. Structural biology of plant sulfur metabolism: From assimilation to biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012, 29, 1138–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naur, P.; Petersen, B.L.; Mikkelsen, M.D.; Bak, S.; Rasmussen, H.; Olsen, C.E.; Halkier, B.A. CYP83A1 and CYP83B1, two nonredundant cytochrome P450 enzymes metabolizing oximes in the biosynthesis of glucosinolates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, M.D.; Naur, P.; Halkier, B.A. Arabidopsis mutants in the C–S lyase of glucosinolate biosynthesis establish a critical role for indole-3-acetaldoxime in auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 2004, 37, 770–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas Grubb, C.; Zipp, B.J.; Ludwig-Müller, J.; Masuno, M.N.; Molinski, T.F.; Abel, S. Arabidopsis glucosyltransferase UGT74B1 functions in glucosinolate biosynthesis and auxin homeostasis. Plant J. 2004, 40, 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gachon, C.M.; Langlois-Meurinne, M.; Henry, Y.; Saindrenan, P. Transcriptional co-regulation of secondary metabolism enzymes in Arabidopsis: Functional and evolutionary implications. Plant Mol. Biol. 2005, 58, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderby, I.E.; Geu-Flores, F.; Halkier, B.A. Biosynthesis of glucosinolates–gene discovery and beyond. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinte, M.M.; Steenkamp, P.A.; Piater, L.A.; Dubery, I.A. Lipopolysaccharide perception in Arabidopsis thaliana: Diverse LPS chemotypes from Burkholderia cepacia, Pseudomonas syringae and Xanthomonas campestris trigger differential defence-related perturbations in the metabolome. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 156, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tierens, K.F.J.; Thomma, B.P.; Brouwer, M.; Schmidt, J.; Kistner, K.; Porzel, A.; Mauch-Mani, B.; Cammue, B.P.; Broekaert, W.F. Study of the role of antimicrobial glucosinolate-derived isothiocyanates in resistance of Arabidopsis to microbial pathogens. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellam, A.; Dongo, A.; Guillemette, T.; Hudhomme, P.; Simoneau, P. Transcriptional responses to exposure to the brassicaceous defence metabolites camalexin and allyl-isothiocyanate in the necrotrophic fungus Alternaria brassicicola. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2007, 8, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.D.; Morra, M.J. Control of soil-borne plant pests using glucosinolate-containing plants. Adv. Agron. 1997, 61, 167–231. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam, N.M.; Samudrala, D.; Harren, F.J.; Cristescu, S.M. Real-time analysis of sulfur-containing volatiles in Brassica plants infested with root-feeding Delia radicum larvae using proton-transfer reaction mass spectrometry. AoB Plants 2012, 2012, PLS021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Xie, J.; Lv, J.; Zhang, G.; Hu, L.; Luo, S.; Li, L.; Yu, J. The roles of cruciferae glucosinolates in disease and pest resistance. Plants 2021, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aires, A.; Carvalho, R.; Rosa, E.A.; Saavedra, M.J. Phytochemical characterization and antioxidant properties of baby-leaf watercress produced under organic production system. CyTA J. Food 2013, 11, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.; Bong, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Park, Y.K.; Arasu, M.V.; Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Park, S.U. De novo transcriptome analysis and glucosinolate profiling in watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.). BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keum, Y.S.; Jeong, W.S.; Kong, A.T. Chemoprevention by isothiocyanates and their underlying molecular signaling mechanisms. Mutat. Res. /Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2004, 555, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Yoshimoto, M.; Murata, Y.; Shimoishi, Y.; Asai, Y.; Park, E.Y.; Sato, K.; Nakamura, Y. Papaya seed represents a rich source of biologically active isothiocyanate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 4407–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahey, J.W.; Zalcmann, A.T.; Talalay, P. The chemical diversity and distribution of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates among plants. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 5–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartea, M.E.; Velasco, P. Glucosinolates in Brassica foods: Bioavailability in food and significance for human health. Phytochem. Rev. 2001, 7, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Mukherjee, S.; Biswas, J.; Roy, M. Sulphoraphane, a naturally occurring isothiocyanate induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells by targeting heat shock proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 427, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.B. Glucosinolates, structures and analysis in foods. Anal. Methods 2010, 2, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Schoene, N.W.; Milner, J.A.; Kim, Y.S. Broccoli-derived phytochemicals indole-3-carbinol and 3,3′-diindolylmethane exerts concentration-dependent pleiotropic effects on prostate cancer cells: Comparison with other cancer preventive phytochemicals. Mol. Carcinog. 2012, 51, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagraj, G.S.; Chouksey, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Broccoli. In Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Fruits and Vegetables; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherland; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, M.; Chatterjee, S. Strategies to Control Cancer by Chinese Cabbage and Anise Seed. In Seeds: Anti-Proliferative Storehouse for Bioactive Secondary Metabolites; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 707–726. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ammar, H. Epigenetic Regulation of Glucosinolate Biosynthesis: Mechanistic Insights and Breeding Prospects in Brassicaceae. DNA 2025, 5, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, B.; Bisht, N.C. Glucosinolates: Regulation of biosynthesis and hydrolysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 620965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barickman, T.C.; Kopsell, D.A.; Sams, C.E. Impact of nitrogen and sulfur fertilization on the phytochemical concentration in watercress, Nasturtium officinal R. Br. In Proceedings of the II International Symposium on Human Health Effects of Fruits and Vegetables: FAVHEALTH, Houston, TX, USA, 9–13 October 2007; Volume 841, pp. 479–482. [Google Scholar]

- Felker, P.; Bunch, R.; Leung, A.M. Concentrations of thiocyanate and goitrin in human plasma, their precursor concentrations in Brassica vegetables, and associated potential risk for hypothyroidism. Nutr. Rev. 2016, 7, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibrahem, W.; Nguyen, D.H.; Kharrat Helu, N.; Tóth, F.; Nagy, P.T.; Posta, J.; Prokisch, J.; Oláh, C. Health Benefits, Applications, and Analytical Methods of Freshly Produced Allyl Isothiocyanate. Foods 2025, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelen-Eigles, G.; Holden, G.; Cohen, J.D.; Gardner, G. The Effect of Temperature, Photoperiod, and Light Quality on Gluconasturtiin Concentration in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsiogianni, M.; Anestopoulos, I.; Kyriakou, S.; Trafalis, D.T.; Franco, R.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I. Benzyl and phenethyl isothiocyanates as promising epigenetic drug compounds by modulating histone acetylation and methylation marks in malignant melanoma. Investig. New Drugs 2021, 39, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahani, S.; Behzadfar, F.; Jahani, D.; Ghasemi, M.; Shaki, F. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of Nasturtium officinale involved in attenuation of gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2017, 27, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.I.; Haldar, S.; Boyd, L.A.; Bennett, R.; Whiteford, J.; Butler, M.; Pearson, J.R.; Bradbury, I.; Rowland, I.R. Watercress supplementation in diet reduces lymphocyte DNA damage and alters blood antioxidant status in healthy adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanparast, R.; Bahramikia, S.; Ardestani, A. Nasturtium officinale reduces oxidative stress and enhances antioxidant capacity in hypercholesterolaemic rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2008, 172, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klimek-Szczykutowicz, M.; Szopa, A.; Korona-Głowniak, I.; Ekiert, H. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of nasturtium officinale (watercress)–rita® bioreactor grown in vitro cultures and herb extracts. In Proceedings of the 3-rd ICPMS Martin, Kraków, Szeged, 24–26 September 2020; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho-Corona, M.D.R.; Ramírez-Cabrera, M.A.; Santiago, O.G.; Garza-González, E.; Palacios, I.D.P.; Luna-Herrera, J. Activity against drug resistant-tuberculosis strains of plants used in Mexican traditional medicine to treat tuberculosis and other respiratory diseases. Phytother. Res. 2008, 22, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spínola, V.; Pinto, J.; Castilho, P.C. In vitro studies on the effect of watercress juice on digestive enzymes relevant to type 2 diabetes and obesity and antioxidant activity. J. Food Biochem. 2017, 41, E12335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Zinadah, O.A. Using nigella sativa oil to treat and heal chemical induced wound of rabbit skin. JKAU Sci. 2009, 21, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettega, P.V.C.; Johann, A.C.B.R.; Alanis, L.R.A.; Bazei, I.F.; Miguel, O.G. Experimental confirmation of the utility of Nasturtium officinale used empirically as mouth lesion repairing promotor. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. 2016, 5, 1161–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Yaricsha, C.A. ACE inhibitory activity, total phenolic and flavonoid content of watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.) extract. Pharmacogn. J. 2017, 9, 249–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa-Al-Reza Hadjzadeh, Z.R.; Moradi, R.; Ghorbani, A. Effects of hydroalcoholic extract of watercress (Nasturtium officinale) leaves on serum glucose and lipid levels in diabetic rats. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2015, 59, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, R.; Kumar, S.; Malik, J.; Singh, G.; Siroliya, V.K. A Review of the Phytochemical and Pharmacological Potential of the Watercress Plant (Nasturitium Officinale): A Medicinal Plant. Int. J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. Arch. 2023, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed, M.K.; Umar, W.; Razzaq, A.; Aziz, T.; Maqsood, M.A.; Wei, S.; Niu, Q.; Huang, D.; Chang, L. Differential metabolic responses of lettuce grown in soil, substrate and hydroponic cultivation systems under NH4+/NO3− application. Metabolites 2022, 12, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardar, G.; Altıkatoğlu, M.; Ortaç, D.; Cemek, M.; Işıldak, İ. Measuring calcium, potassium, and nitrate in plant nutrient solutions using ion-selective electrodes in hydroponic greenhouse of some vegetables. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2015, 62, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lira, R.M.; Silva, Ê.F.; Silva, G.F.; Soares, H.R.; Willadino, L.G. Growth, water consumption and mineral composition of watercress under hydroponic system with brackish water. Hortic. Bras. 2018, 36, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irhayyim, T.; Fehér, M.; Lelesz, J.; Bercsényi, M.; Bársony, P. Nutrient removal efficiency and growth of watercress (Nasturtium officinale) under different harvesting regimes in integrated recirculating aquaponic systems for rearing common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.). Water 2020, 12, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitrago-Villanueva, I.; Barbosa-Cornelio, R.; Coy-Barrera, E. Specialized Metabolite Profiling-Based Variations of Watercress Leaves (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.) from Hydroponic and Aquaponic Systems. Molecules 2025, 30, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, A.H.; Li, G.; Zelmer, C.D.; McVetty, P.B.; Asif, M.; Goyal, A. Molecular genetics of glucosinolate biosynthesis in Brassicas: Genetic manipulation and application aspect. In Crop Plant; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2012; pp. 189–216. [Google Scholar]

- Kopsell, D.A.; Barickman, T.C.; Sams, C.E.; McElroy, J.S. Influence of Nitrogen and Sulfur on Biomass Production and Carotenoid and Glucosinolate Concentrations in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale R. Br.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10628–10634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu Ting, C.T.; Peng Chang, P.C.; Guo LiPing, G.L. Effect of MgSO4 treatment on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in broccoli sprouts. Food Sci. 2018, 39, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ambawat, S.; Sharma, P.; Yadav, N.R.; Yadav, R.C. MYB transcription factor genes as regulators for plant responses: An overview. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2013, 19, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, P.; Nirasawa, S.; Liu, H. Formation, immunomodulatory activities, and enhancement of glucosinolates and sulforaphane in broccoli sprouts: A review for maximizing the health benefits to human. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 7118–7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Balibrea, S.; Moreno, D.A.; García-Viguera, C. Glucosinolates in broccoli sprouts (Brassica oleracea var. italica) as conditioned by sulphate supply during germination. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C673–C677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Degryse, F.; Wu, J.; Huang, C.; Yu, Y.; Mclaughlin, M.J.; Zhang, F. Slow-and fast-release magnesium-fortified macronutrient fertilizers improve plant growth with lower Mg leaching loss. J. Soils Sediments 2024, 24, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, B.; Kumar, P.; Bisht, N.C. Defense versus growth trade-offs: Insights from glucosinolates and their catabolites. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 2964–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Gautam, P.; Sen, S. Soil Test Crop Response-Based Fertilizer Application Improves Soil Fertility and Wheat (Triticum Aestivum L.) Productivity Grown After Direct-Seeded Rice in Mollisols of Northern India. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2025, 56, 1767–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopriva, S.; Mugford, S.G.; Matthewman, C.; Koprivova, A. Plant sulfate assimilation genes: Redundancy versus specialization. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambo, P.; Nicoletto, C.; Giro, A.; Pii, Y.; Valentinuzzi, F.; Mimmo, T.; Lugli, P.; Orzes, G.; Mazzetto, F.; Astolfi, S.; et al. Hydroponic solutions for soilless production systems: Issues and opportunities in a smart agriculture perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, T.D.; Pinto, J.R.; Davis, A.S. Fertigation-Injecting soluble fertilizers into the irrigation system. In Forest Nursery Notes, Volume 29, Issue 2; Kasten, D.R., Tom, L.D., Eds.; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Natural Resources Conservation Service, National Agroforestry Center: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2009; Volume 4, pp. 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L. Hydroponics and Protected Cultivation: A Practical Guide; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L. Plant nutrition and nutrient formulation. In Hydroponics and Protected Cultivation: A Practical Guide; CABI: Wall-ingford, UK, 2021; pp. 136–169. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Ö. Velocity Analysis and Statics Corrections. In Seismic Data Analysis; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 2001; pp. 271–461. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Z.; Zhou, P.C.; Fan, Z.T.; Wei, F.; Qin, S.S.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Chen, L.Y.; Wei, K.H. Multi-omics analysis uncovers the transcriptional regulatory mechanism of magnesium Ions in the synthesis of active ingredients in Sophora tonkinensis. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reginato, M.; Luna, V.; Papenbrock, J. Current knowledge about Na2SO4 effects on plants: What is different in comparison to NaCl? J. Plant Res. 2021, 134, 1159–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero-Marcos, M.; Lasa, B.; Neves, T.; Zamarreño, Á.M.; García-Mina, J.M.; García-Olaverri, C.; Aparicio-Tejo, P.M.; Cruz, C.; Ariz, I. Plant ammonium sensitivity is associated with external pH adaptation, repertoire of nitrogen transporters, and nitrogen requirement. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 3557–3578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, V.; Faiz, S.; Jamwal, S.; Bhagnyal, D.; Bhasin, S.; Rashid, A.; Vyas, D. Sulfate and chloride ions differentially affect sulfur and glucosinolate metabolism in Lepidium latifolium L. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithen, R. Sulphur-containing compounds. In Plant Secondary Metabolites: Occurrence, Structure and Role in the Human Diet; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, Y.; Maruyama-Nakashita, A. Biosynthesis of sulfur-containing small biomolecules in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haneklaus, S.; Bloem, E.; Schnug, E. History of sulfur deficiency in crops. In Sulfur: A Missing Link between Soils, Crops, and Nutrition; Book and Multimedia Publishing Committee: Singapore, 2008; Volume 50, pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Krumbein, A.; Schonhof, I.; Rühlmann, J.; Widell, S. Influence of sulphur and nitrogen supply on flavour and health-affecting compounds in Brassicaceae. In Plant Nutrition: Food Security and Sustainability of Agro-Ecosystems Through Basic and Applied Research; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 294–295. [Google Scholar]

- Traka, M.H.; Saha, S.; Huseby, S.; Kopriva, S.; Walley, P.G.; Barker, G.C.; Moore, J.; Mero, G.; van den Bosch, F.; Constant, H.; et al. Genetic regulation of glucoraphanin accumulation in Beneforté® broccoli. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Hussain, M.; Anarjan, M.B.; Lee, S. Examination of glucoraphanin content in broccoli seedlings over growth and the impact of hormones and sulfur-containing compounds. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 14, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulc, P.M.; Drozdowska, L.; Kachlicki, P. Effect of sulphur on the yield and content of glucosinolates in spring oilseed rape seeds. Electron. J. Pol. Agric. Univ. 2003, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kacjan Maršić, N.; Može, K.S.; Mihelič, R.; Nečemer, M.; Hudina, M.; Jakopič, J. Nitrogen and sulphur fertilisation for marketable yields of cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. Capitata), leaf nitrate and glucosinolates and nitrogen losses studied in a field experiment in Central Slovenia. Plants 2021, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Han, Y.; Gu, Z. Physiological and biochemical metabolism of germinating broccoli seeds and sprouts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafin-Andrzejewska, M.; Marcin, K.; Kotecki, A. Effect of different sulfur fertilizer doses on the glucosinolate content and profile of white mustard seeds. J. Elem. 2020, 25, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Zhang, B.; Bozdar, B.; Chachar, S.; Rai, M.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Hayat, F.; Chachar, Z.; Tu, P. The power of magnesium: Unlocking the potential for increased yield, quality, and stress tolerance of horticultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1285512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui-xiao, L.A.; Ping, F.A.N.G.; Yi-bo, T.E.N.G.; Ya-juan, L.I.; Xian-yong, L.I.N. Effect of nitrogen level on growth and glucosinolates content of Chinese kale. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 2009, 15, 429–434. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.J.; Zhu, Z.J.; Ni, X.L.; Qian, Q.Q. Effect of nitrogen and sulfur supply on glucosinolates in Brassica campestris ssp. chinensis. Agric. Sci. China 2006, 5, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitainda, V.; Jez, J.M. Kinetic and catalytic mechanisms of the methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis enzyme methylthioalkylmalate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendening, T.M.; Poulton, J.E. Glucosinolate Biosynthesis: Sulfation of Desulfobenzylglucosinolate by Cell-Free Extracts of Cress (Lepidium sativum L.) Seedlings. Plant Physiology. 1988, 86, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Augustyn, A.; Johansson, A.J.; Borowski, T. Mechanism of Sulfate Activation Catalyzed by ATP Sulfurylase—Magnesium Inhibits the Activity. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohinc, T.; Trdan, S. Environmental factors affecting the glucosinolate content in Brassicaceae. J. Food Agric. Env. 2012, 10, 357. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, P.; Di, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Huang, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; Sun, B. Light irradiation maintains the sensory quality, health-promoting phytochemicals, and antioxidant capacity of post-harvest baby mustard. J. Food Sci. 2020, 87, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonious, G.F.; Bomford, M.; Vincelli, P. Screening Brassica species for glucosinolate content. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part B 2009, 44, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huseby, S.; Koprivova, A.; Lee, B.R.; Sahar, S.; Mithen, R.; Wold, A.B.; Bengtsson, G.B.; Kopriva, S. Diurnal and light regulation of sulphur assimilation and glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1039–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hong, S.B.; Yang, B.; Zang, Y. Melatonin elevated Sclerotinia sclerotiorum resistance via modulation of ATP and glucosinolate biosynthesis in Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis. J. Proteom. 2021, 243, 104264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkman, M.; Klingen, I.; Birch, A.N.; Bones, A.M.; Bruce, T.J.; Johansen, T.J.; Meadow, R.; Mølmann, J.; Seljåsen, R.; Smart, L.E.; et al. Phytochemicals of Brassicaceae in plant protection and human health–Influences of climate, environment and agronomic practice. Phytochemistry 2011, 72, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuong, D.M.; Park, C.H.; Bong, S.J.; Kim, N.S.; Kim, J.K.; Park, S.U. Enhancement of glucosinolate production in watercress (Nasturtium officinale) hairy roots by overexpressing cabbage transcription factors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 4860–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaschetto, L.M. DNA Methylation, Histone Modifications, and Non-coding RNA Pathways. In Epigenetics in Crop Improvement: Safeguarding Food Security in an Ever-Changing Climate; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mitreiter, S.; Gigolashvili, T. Regulation of glucosinolate biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittipol, V.; He, Z.; Wang, L.; Doheny-Adams, T.; Langer, S.; Bancroft, I. Genetic architecture of glucosinolate variation in Brassica napus. J. Plant Physiol. 2019, 240, 152988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, A.H.K.; Yi, G.E.; Laila, R.; Yang, K.; Park, J.I.; Kim, H.R.; Nou, I.S. Expression profiling of glucosinolate biosynthetic genes in Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata inbred lines reveals their association with glucosinolate content. Molecules 2016, 21, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Glucosinolate | 1 Chemical Structure | Source | Breakdown Product | Health Relevance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucotropaeolin |  | Red cabbage, mustard | Benzyl isothiocyanate | Neuroprotection and diabetes control agent | [51,52] |

| Papaya seeds | |||||

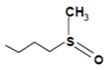

| Glucoerucin |  | Rocket, broccoli | 4-methylthiobutyl isothiocyanate (erucin) | Anticancer | [53] |

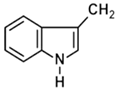

| Neoglucobrassicin |  | Red cabbage, Chinese cabbage | N-methoxyindole-3-carbinol | Anticancer | [54] |

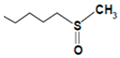

| Glucobrassicanapin |  | Turnip green and swede | 4-methylsulfinylbutyl isothiocyanate | Antimicrobial activity | [55] |

| Glucoraphanin |  | Cauliflower, broccoli, kale | Sulforaphane | Anticancer | [56,57] |

| Glucobrassicin |  | Cabbage, brussels sprout | Indole-3-carbinol | Anticancer | [58] |

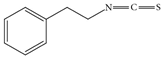

| Gluconasturtiin |  | Watercress, broccoli, turnips | 2-phenylethyl isothiocyanate. | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [59] |

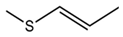

| Glucoraphasatin |  | Radish sprouts | 4-methylsulfanyl-3-butenyl isothiocyanate | Antioxidant and anticancer | [60] |

| Glucoiberin |  | White cauliflower, savoy cabbage | 3-Methylsulfinyl propyl isothiocyanate | Chemo preventive | [61] |

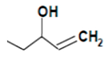

| Progoitrin |  | Mustard greens, turnip, rapeseed | 5-Ethenyl-1,3-oxazolidine-2-thione | Inhibition of thyroid hormone synthesis | [62] |

| Sinigrin |  | Mustard, horseradish | Allyl isothiocyanate | Antimicrobial and pungency | [63] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Makumbe, H.H.; Nzaramyimana, T.; Kabanda, R.; Antonious, G.F. Effects of Magnesium Sulphate Fertilization on Glucosinolate Accumulation in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale). Int. J. Plant Biol. 2025, 16, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040137

Makumbe HH, Nzaramyimana T, Kabanda R, Antonious GF. Effects of Magnesium Sulphate Fertilization on Glucosinolate Accumulation in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale). International Journal of Plant Biology. 2025; 16(4):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040137

Chicago/Turabian StyleMakumbe, Hattie Hope, Theoneste Nzaramyimana, Richard Kabanda, and George Fouad Antonious. 2025. "Effects of Magnesium Sulphate Fertilization on Glucosinolate Accumulation in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale)" International Journal of Plant Biology 16, no. 4: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040137

APA StyleMakumbe, H. H., Nzaramyimana, T., Kabanda, R., & Antonious, G. F. (2025). Effects of Magnesium Sulphate Fertilization on Glucosinolate Accumulation in Watercress (Nasturtium officinale). International Journal of Plant Biology, 16(4), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijpb16040137