Abstract

Picea jezoensis (Siebold & Zucc.) Carrière forests are distributed in Korea and China and are crucial for phytogeographical research. Implementing conservation policies encompassing multiple species is necessary to conserve endangered species, particularly monitoring coexisting species and their interactions within an ecological network. Here, we identified plants within P. jezoensis forests in East Asia as generalist species to contribute foundational data for biodiversity conservation. We examined 91 standardized sites through the Braun-Blanquet method, while generalist indices were calculated using Levin’s method. The top 5% of generalists in the P. jezoensis forests were Acer komarovii (0.7409), Betula ermanii (0.7214), Asarum sieboldii (0.7002), Lepisorus ussuriensis (0.6977), Acer pseudosieboldianum (0.6915), Tripterygium regelii (0.6876), Thelypteris phegopteris (0.6771), Dryopteris expansa (0.6745), Sorbus commixta (0.6642), and Rhododendron schlippenbachii (0.6625). Correlation analysis between ecological factors and generalist species revealed that the coverage of Abies spp., Acer spp., and Rhododendron spp. and the species diversity index were influenced by altitude. Convex hull analysis revealed that pteridophytes and broad-leaved plants regenerated through stump sprouts occupy ecological niche spaces, indicating diverse habitats within P. jezoensis forests. This study highlights the importance of the simultaneous monitoring of multiple species to conserve ecosystem health and offers broader implications for ecological understanding.

1. Introduction

An ecological niche refers to the physical space where an organism survives and lives, influencing its function and role as an organism in the ecosystem. It is closely associated with the distribution and scope of organisms [1,2] and serves as a shelter for plants, providing them with limited resources for their growth and survival. Various factors significantly influence the distribution of plant species in an ecosystem. Among these, topographic features play a crucial role in changing the complexity of the structure and function of vegetation [3].

Rapoport’s rule is a representative hypothesis related to species distribution, which suggests that the species diversity and ecological niche increase when moving from the equator toward the poles [1]. This evidence suggests that physical distance, such as topographical differences among species, influences the availability of resources necessary for survival. Ecologists have thus shown interest in understanding the changes in ecological niche mechanisms associated with species’ physical distance and topographic features’ variations. For instance, environmental factors (such as soil physicochemical properties, air temperature, and relative humidity) differ depending on topographic features such as elevation and latitude), suggesting that these variations could influence species distribution [4,5]. Environmental changes also affect the composition of vegetation species in a particular area, leading to interspecific competition [6]. In topographies with diverse features, various species appear and are considered generalists owing to their wide range of available resources within a particular vegetation. They are defined as abundant species and well-adapted to environments owing to their wide range of tolerance limits and widespread distribution [7]. They also serve as indicator species within specific ecosystems and play a crucial role in maintaining the stability of ecosystem networks. Thus, the observation of generalists in specific ecosystems is important to assess and confirm the overall health of ecosystems.

Meanwhile, alpine conifer species are experiencing rapid declines in population and habitat due to the ongoing climate crisis. The alpine region has a harsh ecological environment for plant species, characterized by moisture stress, strong winds, and soil erosion [8,9,10,11,12,13].

Picea jezoensis (Siebold & Zucc.) Carrière, an endangered conifer species, is listed as Least Concern on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. It is predominantly found in alpine areas above 1300 m above sea level [14,15]. P. jezoensis is the most widely distributed species in the sub-alpine forests of Northeast Asia, specifically in Korea, Manchuria, China, Russia, and Japan. Although it has recently maintained good populations in relatively cold habitats at high latitudes, populations are declining in low-latitude areas, such as Korea and the Changbai Mountain areas in China [14,16,17,18,19,20]. Therefore, identifying the ecosystem structures of P. jezoensis in South Korea and China (areas near Changbai Mountain) is crucial for observing the southern limit lines of this vegetation. On a global scale, changes in the distribution of P. jezoensis forests are observed in these areas, which are worthy of conservation from a phytogeographical perspective [12,20]. By formulating proactive national and international conservation strategies, the implementation of ecosystem management through the maintenance and enhancement of biodiversity should be prioritized [21].

Complex interrelationships exist between biotic and abiotic factors in ecosystems, and effective conservation of a particular species requires the simultaneous monitoring of neighboring species that share the same spatial extent. To conserve endangered species, it is necessary to implement conservation policies encompassing multiple species rather than a single species [22,23]. In short, active vegetation dynamics, facilitated by spatially flexible relationships, are crucial in maintaining healthy biodiversity within ecosystems. Thus, investigating the dynamics of co-occurring plant species in P. jezoensis communities is essential for conserving P. jezoensis, which first requires the selection of generalists based on species distribution.

This study aimed to select generalist plant species based on their ecological niche and analyze correlations between environmental factors and the topography. This study focused on the plants in Korea and parts of China that correspond to the southern limit line of the P. jezoensis forest in East Asia. The study results can provide basic data for conserving the P. jezoensis forest in East Asia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Target Site

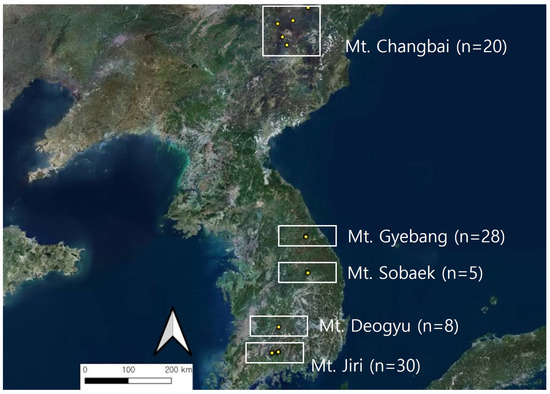

This study investigated 91 standardized sites in five P. jezoensis habitats located in Gyebang (n = 28), Sobaek (n = 5), Deogyu (n = 8), and Jiri Mountains (n = 30) in South Korea, and Baekdu Mountain (n = 20) in China (Figure 1). Ninety-one circular sample plots, each covering an area of 400 m2, were set up in standardized sites. The study targeted overstory and understory vegetation within a radius of 11.3 m.

Figure 1.

Survey plots of Picea jezoensis habitat in East Asia.

The geographical distribution of the standardized survey plots is as follows: latitude 35°18′42″–42°30′6″ and longitude 127°33′53″–128°38′55″; the average elevation was 1492.5 ± 22.9 m and average slope was 24.0 ± 1.0°. Azimuth slopes were as follows: north at 27.6%, east at 18.4%, south at 14.9%, and west at 39.1%.

We analyzed meteorological data considering the 30-year climate characteristics (1991–2020) from the Korea Meteorological Administration for South Korea and the Changbai Mountain area in China. The data from the closest meteorological stations in the five regions per habitat were utilized: the data from the Hongcheon Meteorological Station for Gyebang Mountain, the Yeongju Meteorological Station for Sobaek Mountain, the Geochang Meteorological Station for Deogyu Mountain, the Sancheong Meteorological Station for Jiri Mountain, and the Samjiyeon Meteorological Station for Changbai Mountain [24]. South Korea is in a mid-latitude temperate climate zone characterized by four distinct seasons: sunny and dry in spring and fall, hot and humid in summer owing to the influence of the North Pacific anticyclone, and cold and dry in winter. The Changbai Mountain area in China has a cooler and drier continental climate than South Korea, with an annual temperature of approximately 36 °C. The average maximum monthly temperatures are as follows: 25.0 °C at Gyebang Mountain, 24.5 °C at Sobaek Mountain, 18.8 °C at Deogyu Mountain, 25.7 °C at Jiri Mountain, and 7.7 °C at Changbai Mountain. The average monthly temperatures are as follows: 11.5 °C at Gyebang Mountain, 11.8 °C at Sobaek Mountain, 12.2 °C at Deogyu Mountain, 13.3 °C at Jiri Mountain, and 10.0 °C at Changbai Mountain. The average monthly minimum temperatures are as follows: −0.8 °C at Gyebang Mountain, −0.2 °C at Sobaek Mountain, 6.5 °C at Deogyu Mountain, 2.0 °C at Jiri Mountain, and –5.3 °C at Changbai Mountain. Deogyu and Jiri Mountains show relatively mild temperatures. The annual precipitation is as follows: 1134.5 mm at Gyebang Mountain, 1274.7 mm at Sobaek Mountain, 1226.1 mm at Deogyu Mountain, 1551.7 mm at Jiri Mountain, and 950.8 mm at Changbai Mountain, and Jiri Mountain has the highest precipitation.

2.2. Field Survey Method

To conduct the vegetation survey in the target site, the layered structure of vegetation within the survey sites was classified into four distinct layers: tree layer, low-tree layer, shrub layer, and herbaceous layer. After identifying the plant species in each layer, we utilized the Braun-Blanquet phytosociological method [25] to assess the coverage and dominance. And we analyzed the median values of these classes as referenced below. The identification of plants was conducted based on the Colored Flora of Korea [26] for plant classification, and the identification of pteridophytes was conducted using the illustrated guide to Korean pteridophytes [27]. Scientific names and species names in Korean followed the Korean Plant Name Index [28], as the Korea National Arboretum and the Korean Society of Plant Taxonomists recommended. The survey was conducted from September 2019 to October 2022.

2.3. Statistical and Analytical Methods

Before analyzing the indicator species in this study, we examined species-area curves to confirm whether the appropriate number of standardized survey plots for the analysis was met [29]. We estimated the species number by randomly selecting the order of the cumulative survey sites in the species-area curves using a table of random sampling numbers, assigning serial numbers for 91 survey sites using the Chao1 estimator [30]. The ecological niche index was calculated using the following formula suggested by Levins [31]:

where E is Levin’s ecological niche breadth, Pik is the relative species composition of a given species (i) to the whole gradient in realized gradient ‘S’, and S is the total number of gradients.

The environmental gradients used in the analysis were divided into vertical and horizontal distributions, and they were grouped as shown in Table 1, considering the minimum and maximum values of the topographical data.

Table 1.

Environmental factors for analyzing ecological niche breadth.

The data used for relative species composition were analyzed based on two parameters: coverage and dominance. Moreover, topographic characteristics determined five environmental gradient factors: vertical distribution (elevation) and horizontal distribution (e.g., latitude, habitat, slope, and azimuth). According to the environmental gradient factor, the ecological niche index ranges between 0 and 1, and a value closer to 1 indicates a species widely distributed according to topographic characteristics.

We also conducted a non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMS) analysis to examine the environmental impact factors of generalist species and assess interspecific correlations. This approach is primarily applied to vegetation data, specifically ecosystem data, exhibiting a non-parametric pattern, and the interpretation can be made by representing correlations between biotic and abiotic factors in two dimensions [32]. We utilized the mean values of coverage and dominance of each plant species within the survey plots, and the Sørenson distance was used as the distance scale. Convex hull measurements were conducted to confirm the two-dimensional spatial range of each generalist according to species composition within the survey sites of the P. jezoensis forests. Convex hull can identify the correlations of ecological niches among species by visualizing measured values on spatial distribution after filtering out specific species’ habitats within a community [33]. We used PC-ORD (ver. 7.0) as the analysis program [32]. The statistical analysis of topographical conditions was conducted using ANOVA, and post hoc testing was performed using Tukey’s method. The topographical survey utilized a clinometer manufactured by Suunto (Tandem/360PC/360R DG CLINO/COMPASS) to measure the slope and azimuth. Rock exposure was assessed by investigating the rock ratio within a circular area with a radius of 11.3 m. Elevation was recorded using the numerical values from a GPS receiver (Table 2), the plant coverage values were determined using the Median Value according to the Braun-Blanquet method as presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Information on the Picea jezoensis forest survey areas from South Korea to China (a, b, and c indicate different delimiters in the ANOVA post hoc test (Tukey’s post hoc), * p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Braun-Blanquet cover-dominance scale.

3. Results

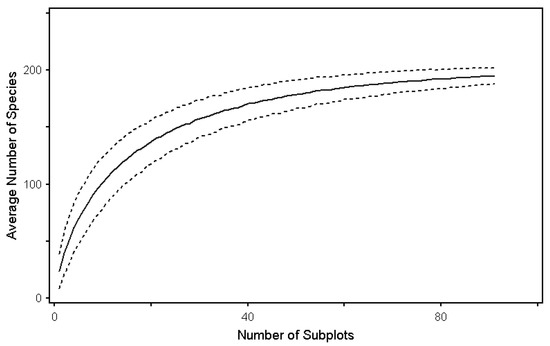

3.1. Species-Area Curves

To examine whether the appropriate quadrats were installed in the target sites, species-area curves were analyzed by estimating the number of species per level after dividing them into crown and understory vegetation (Figure 2). Consequently, based on the number of survey plots, the slope for species richness converged to 0, suggesting that an appropriate number of quadrats was installed for the vegetation analysis in the target site.

Figure 2.

Species-area curves of forest layers by estimating species richness using the Chao1 estimator. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

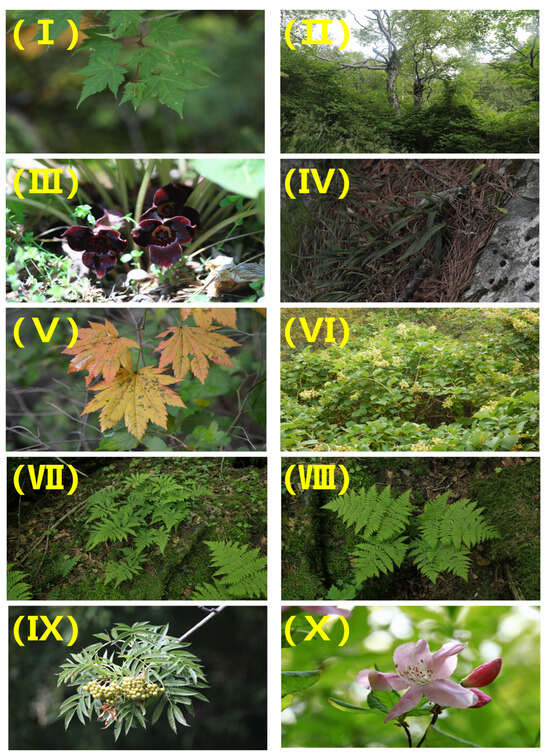

3.2. Selection of Generalist Species

The list of vascular plant species found in the 91 survey sites is presented in Table 4. In total, 202 taxa were identified, including 59 families, 127 genera, 171 species, 2 subspecies, 26 varieties, and 3 forms. The results of selecting generalist species of the P. jezoensis forests in East Asia are presented in Table 5. The identified generalists are the top 10 species in the ecological niche index, representing 5% of the plant species found. After calculating the ecological niche index for each species based on five topographic characteristics, we selected the final generalists based on their average values. The ecological niche index of P. jezoensis, the target species in this study, was 0.7411, and the top 10 generalists were as follows (Figure 3): Acer komarovii Pojark. (0.7409), Betula ermanii Cham. (0.7214), Asarum sieboldii Miq. (0.7002), Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching (0.6977), Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom. (0.6915), Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda (0.6876), Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss. (0.6771), Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy (0.6745), Sorbus commixta Hedl. (0.6642), and Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim. (0.6625).

Table 4.

List of plant species in the Picea jezoensis forest.

Table 5.

List of generalists in Picea jezoensis habitats in East Asia (above 5% in total species [202 taxa], ×1: altitude, ×2: latitude. ×3: habitat, ×4: slope, and ×5: azimuth, Refer to Appendix A for the niche breathe of plant species observed).

Figure 3.

Pictures of generalists ((I) Acer komarovii Pojark; (II) Betula ermanii Cham; (III) Asarum sieboldii Miq; (IV) Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching; (V) Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom.; (VI) Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda; (VII) Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss.; (VIII) Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy; (IX) Sorbus commixta Hedl.; (X) Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim.).

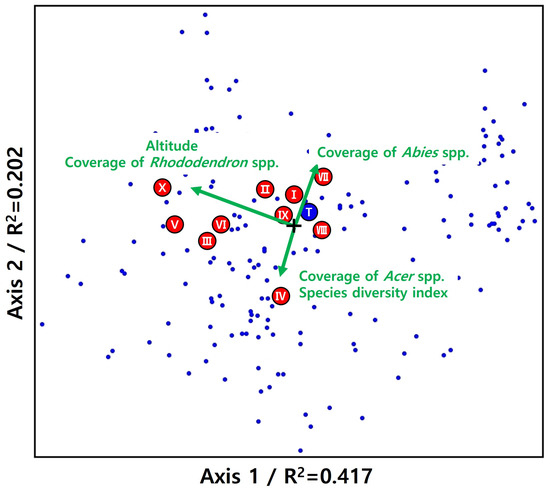

3.3. Correlations between Environmental Factors

The results of the correlation analysis between environmental factors of generalist plant species within the P. jezoensis forests are presented in Figure 4. The explanatory power of the NMS ordination was 0.417 and 0.202 for the first and second axes, respectively, resulting in a total explanatory power of 0.619. The correlation factors were elevation, Rhododendron spp. coverage, Abies spp. coverage, Acer spp. coverage, and the species diversity index. The correlation between Abies spp. coverage and Acer spp. coverage was heterogeneous. The generalist species correlated with the coverage of the genus of Abies were Acer komarovii Pojark., Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss., and P. jezoensis. The one species that showed correlations with Acer spp. coverage and species diversity index was Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching. The species that were correlated with elevation and Rhododendron spp. were Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim., Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom., Asarum sieboldii Miq., and Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda.

Figure 4.

The distribution of the 10 generalists in two-dimensional space and correlation with environmental factors (NMS ordination was used, Total R2 = 0.619, cut off = 0.3). Blue dots represent the two-dimensional spatial distribution of emerging species (I, Acer komarovii Pojark; II, Betula ermanii Cham; III, Asarum sieboldii Miq; IV, Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching; V, Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom.; VI, Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda; VII, Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss.; VIII, Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy; IX, Sorbus commixta Hedl.; X, Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim.).

The habitat of P. jezoensis in Korea reportedly has the same habitat status as that of sub-alpine conifers, such as Abies nephrolepis (Trautv. Ex Maxim.) Maxim. and Abies koreana E. H. Wilson [12,13]; our study yielded the same results. Notably, Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim. is a species that typically thrives at high altitudes, frequently appearing in habitats where the Rhododendron spp. is prevalent [12].

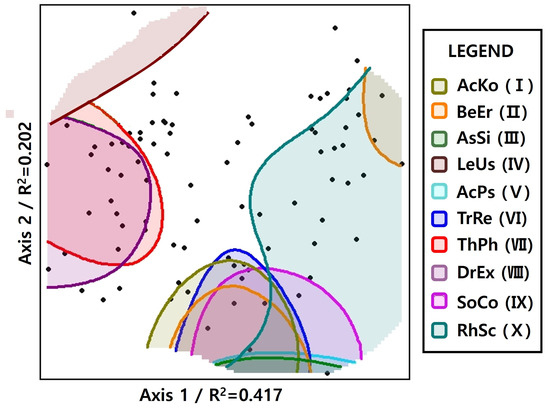

3.4. Convex Hull

A two-dimensional representation of the ecological niche range of generalists as determined through convex hull analysis is shown in Figure 5. The area shown in the convex hull result indicates the diversity of species composition and complexity of vegetation structure in the survey plot to which the generalist belongs. Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim. was found in various vegetation structure types. In addition, Acer komarovii Pojark., Betula ermanii Cham., Asarum sieboldii Miq., Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching, Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom., Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda, and Sorbus commixta Hedl. were identified with ecological niches distributed within similar species composition structures. Meanwhile, pteridophytes or epiphytes such as Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss., Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy, and Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching exhibited a heterogeneous spatial distribution.

Figure 5.

The convex hull graph shows the ecological niche of 10 generalists in the Picea jezoensis habitat from South Korea to China (black dots represent survey plots by calculating the species composition value on a two-dimensional axis, AcKo (I), Acer komarovii Pojark; BeEr (II), Betula ermanii Cham.; AsSi (III), Asarum sieboldii Miq.; LeUs (IV), Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching; AcPs (V), Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom.; TrRe (VI), Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda; Th Ph (VII), Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss.; DrEx (VIII), Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy; SoCo (IX), Sorbus commixta Hedl.; RhSc (X), Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim).

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecological Characteristics of Generalist Species

The generalists along the southern limit line of P. jezoensis were identified as the genus Acer and the genus Betula, which are widely distributed plant species. The species of Acer or Betula are noticeable as they are woody plants with the potential to evolve into woody species in sub-alpine ecosystems in the future [20]. These species are widely distributed in sub-alpine coniferous forest zones, including Abies nephrolepis (Trautv. ex Maxim.) Maxim. and Abies koreana E. H. Wilson in Korea. Betula ermanii Cham. was analyzed as a generalist species with the highest vertical range.

P. jezoensis forests in Korea and China are characterized by highly complex and diverse vegetation structures owing to secondary forests. The generalists that exhibit such characteristics are Acer spp. and Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda. In Korea, Acer spp. maintain their ecological niche through sprout regeneration; as the Acer spp. is highly affected by pests in seeds within natural forests, approximately 30% of the seeds produced by an individual are perforated by pests. Approximately 70% of the seeds undergo advanced seed decay, making it difficult to naturally regenerate through seeds [34]. Therefore, most grow by branching out from the root-sucker, forming populations. These growth patterns of broad-leaved species are characteristic of the typical vegetation structure of a secondary forest in Korea. Secondary forests occur in frequent disturbances, leading to the predominant regeneration of vegetation primarily through stump saplings for broad-leaved trees; this forest structure is predominantly found in sub-alpine coniferous forests in Korea [20].

Meanwhile, Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda vigorously reproduces after the occurrence of a forest gap, making it a major species for confirming disturbance frequencies within forest stands [13,20]. After the occurrence of forest gaps, secondary forests undergo dynamic transitions, experiencing frequent disturbances until the crown layer within the forest become stable [35]. Regarding Betula ermanii Cham., Asarum sieboldii Miq., Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom., Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda, and Sorbus commixta Hedl., multiple generalists have the same ecological niche ranges, indicating that they are simultaneously found in similar vegetation structures. This phenomenon is speculated to be the result of a highly dynamic response to changes in vegetation structure caused by frequent disturbances, particularly forest gaps; these disturbances, involving the repeated opening and closing of canopies, affect species richness within the vegetation, contributing to the complexity in vegetation structure [20,36,37]. This is assumed to result from natural disturbances driven by conditions such as wind damage and moisture deficit in the sub-alpine zone of the P. jezoensis forests [8,9,11,12].

In addition, pteridophyte species, such as Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss. and Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy, and the epiphyte Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching, exhibited spatial arrangements different from those of other generalists. Epiphytes are plant species that generally thrive in areas with poorly developed soils; they show a unique ecological life history by growing on the surface of other plants and absorbing water and nutrients from the atmosphere and soil through their roots. Furthermore, epiphytes exhibit adaptability to various habitats, including rainforests, deserts, and alpine areas, indicating their ability to survive in diverse environments without being significantly influenced by host specificity [38,39,40]. Our study also revealed their ability to survive in barren environments, such as the habitat for P. jezoensis, indicating adaptation to various stresses.

Pteridophytes, such as Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy and Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss., thrive in environments with abundant moisture in the air and soil and grow in shaded areas or rocky crevices within forests. Pteridophytes also exhibit ecological features, including reproduction via spores and the ability of individuals to thrive in habitats with low moisture stress [41,42,43,44]. Undisturbed areas in the P. jezoensis forests within the southern limit line are expected to have high aerial humidity, and it is assumed that the P. jezoensis forests, where these pteridophytes thrive, have not experienced significant and frequent disturbances. In the future, if natural disturbances occur, forest gaps will form, and the resultant drop in atmospheric humidity can provide a dry environment in the forest, contributing to a decline in pteridophytes; considering this, these species are considered indicator plants that provide insights into disturbance levels.

Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim. belongs to the Rhododendron spp., a shrubby tree species and a plant species with a wide vertical range that can grow above the tree line. The Rhododendron spp., which grows in sub-alpine regions, is widely distributed in East Asia, including Korea and China, and is considered the genus representing the vegetation in Korea [45]. The Rhododendron spp. is an important indicator plant for monitoring, which confirms the shrinkage and expansion of sub-alpine ecosystems in response to global environmental changes [46]. In an analysis of indicator species based on elevation in East Asia, the Rhododendron spp. was identified as an indicator species at high elevations [46]; in this study, the species was the second highest generalist species in terms of elevation, demonstrating a broad vertical range and highlighting its adaptability across diverse elevations.

The selection of generalists within coniferous forests is crucial for predicting future changes in vegetation structures driven by long-term transitions, and such plant species evolve owing to the interrelations among them [47]. The findings of this study will provide a basis for understanding the vegetation structure of climax forests during the transition from coniferous to broadleaf forests.

4.2. Correlations between Generalist Species and Ecological Niche Distribution

Generalist species with equivalent ecological niches demonstrate the same environmental adaptability in the ecosystem [48]. Variations in the ecological niches of plant species within vegetation ultimately reflect differences in their habitats, and plant species with overlapped ecological niches have similar habitats [49].

Examining the ten generalist species in P. jezoensis forests in East Asia found that each species does not have the same habitat type. This study categorized the ecological niche range into two groups: woody broad-leaved species and pteridophytes. This result suggests that the same woody community can consist of different habitats. The most significant difference between the two groups lies in the moisture environment within the vegetation. The broad-leaved tree species group is characterized by irregularities due to frequent disturbances, whereas the pteridophyte group is considered relatively stable. As the broadly distributed pteridophyte group is more sensitive to other environmental factors and occupies a smaller habitat than the woody plant species [50], it is identified as a vegetation structure that should be intensively monitored within P. jezoensis forests.

Seasonal winds are a crucial factor influencing East Asia’s diverse vegetation structure of sub-alpine coniferous forests. The climatic requirement in East Asia is monsoonal winds, vital in determining the vegetation structure. Monsoonal winds are dry and create diverse vegetation types along the vertical range within mountains [51]. This complexity causes diverse habitats, and Picea forests, forming part of the remnant population, are predominantly found in small numbers in areas with frequent disturbances, such as cliffs and rocky terrain [52,53,54,55]. The analysis identified broad-leaved species, such as Acer spp. or Betula spp., as generalists, favoring regeneration through sprouts within secondary forests after frequent disturbance; this observation aligns with the complexity of sub-alpine ecosystems observed in previous studies. The diverse distribution of ecological niches of generalists in P. jezoensis forests at the southern limit line in East Asia, as revealed through convex hull analysis, can be considered an indirect example of the dynamics and diversity of habitats [46].

As the fluctuations in bioclimatic factors increase, the residual community species experiencing unstable climate conditions gradually decline [51]. Therefore, the stability of climatic factors is a prerequisite for protecting specific plant species, and long-term, stable remnant populations, characterized by rich gene pools and species diversity, have the potential for new speciation over time [56,57,58,59,60].

For the sub-alpine remnant populations, unstable climatic requirements disadvantage the in situ survival of specific species. Within forest ecosystems, the complex habitat mosaic suggests that P. jezoensis forests persist as remnant populations within sub-alpine vegetation owing to rising temperatures, with the high dynamics of forest ecosystems rendering it difficult to maintain a stable ecosystem structure [12,14].

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to obtain scientific evidence for conservation policy recommendations to maintain and enhance biodiversity by selecting generalist plant species in P. jezoensis forests in Korea and China. Identifying generalist plant species influenced by topographic features is crucial in formulating effective conservation strategies. However, this study has limitations in quantitative analysis based on short-term vegetation survey data. Thus, it is necessary to clarify changes and patterns through continuous and long-term monitoring of P. jezoensis forests in Northeast Asia, including Korea.

Remnant populations in sub-alpine ecosystems face considerable challenges in directly collecting data on environmental factors owing to the harsh and barren nature of the ecosystems. Therefore, co-occurring species refer to species that naturally appear together with a specific organism or in a particular habitat. These species coexist in a specific environment and can influence or interact with each other. From a conservation perspective, investigating and understanding co-occurring species is essential for comprehending the ecosystem of a specific habitat and designing conservation strategies. Conservation efforts for a particular species require understanding not only the environment in which the species exists but also the roles of other organisms coexisting in that environment. This understanding can provide insights into inter-species interactions and the stability of the habitat ecosystem. This is the ultimate purpose of this study, and the results can provide essential foundational data that can be instrumental in formulating ecosystem conservation policies in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.-J.P. and K.-I.C.; software, B.-J.P.; formal analysis, B.-J.P. and K.-I.C.; investigation, B.-J.P., T.-I.H. and K.-I.C.; writing—original draft, B.-J.P. and T.-I.H.; writing—review and editing, K.-I.C.; data curation, B.-J.P.; visualization, B.-J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Baekdudagan National Arboretum (Project No. 2023-01-01-02) and the National Institution of Ecology (Project No. NIE-B-2024-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted as part of the Baekdudagan National Arboretum’s research project, “Research on the Target Plant Species in Baekdudaegan for Conservation Status Assessments and Strategies (Project No. 2023-01-01-02)” and the National Institution of Ecology’s research project, “Development of Policy Decision Support System Base on Ecosystem Services Assessment (Project No. NIE-B-2024-03)”, and the Korea Environmental Industry & Technology Institute project, “Development of decision support integrated impact assessment model for climate change, adaptation: ecosystem (Project No. 2022003570001)” in Republic of Korea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

List of niche breadth for plants on P. jezoensis habitats (×1: altitude, ×2: latitude, ×3: habitat, ×4: slope, ×5: azimuth).

| Scientific Name | ×1 | ×2 | ×3 | ×4 | ×5 | Mean |

| Abies koreana Wilson | 0.3210 | 0.2000 | 0.2467 | 0.9516 | 0.5379 | 0.4514 |

| Abies nephrolepis (Trautv.) Maxim. | 0.2409 | 0.6784 | 0.4601 | 0.7196 | 0.8919 | 0.5982 |

| Acer barbinerve Maxim. | 0.3842 | 0.7315 | 0.6249 | 0.4055 | 0.4471 | 0.5186 |

| Acer komarovii Pojark. | 0.5506 | 0.6751 | 0.6935 | 0.9049 | 0.8802 | 0.7409 |

| Acer mandshuricum Maxim. | 0.1825 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3702 | 0.3497 | 0.2605 |

| Acer pictum subsp. mono (Maxim.) Ohashi | 0.5180 | 0.5519 | 0.5901 | 0.6604 | 0.5332 | 0.5707 |

| Acer pseudosieboldianum (Pax) Kom. | 0.6544 | 0.4904 | 0.6903 | 0.9025 | 0.7197 | 0.6915 |

| Acer tegmentosum Maxim. | 0.2722 | 0.4916 | 0.4916 | 0.7416 | 0.7063 | 0.5406 |

| Acer ukurunduense Trautv. & C.A.Mey. | 0.2805 | 0.4640 | 0.4600 | 0.5489 | 0.9036 | 0.5314 |

| Aconitum jaluense Kom. | 0.3542 | 0.4565 | 0.4565 | 0.7059 | 0.5415 | 0.5029 |

| Aconitum pseudolaeve Nakai | 0.1429 | 0.3291 | 0.2533 | 0.2953 | 0.2524 | 0.2546 |

| Actaea asiatica H. Hara | 0.1920 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3456 | 0.4253 | 0.2726 |

| Actinidia arguta (Siebold & Zucc.) Planch. ex Miq. | 0.3094 | 0.2443 | 0.2443 | 0.6333 | 0.5115 | 0.3885 |

| Actinidia polygama (Siebold & Zucc.) Planch. ex Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.3812 | 0.2000 | 0.3812 | 0.2383 | 0.2687 |

| Adenophora remotiflora (Siebold & Zucc.) Miq. | 0.2593 | 0.2649 | 0.2649 | 0.4667 | 0.4712 | 0.3454 |

| Agastache rugosa (Fisch. & Mey.) Kuntze | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.8000 | 0.5000 | 0.4771 |

| Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb. | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.3471 |

| Ainsliaea acerifolia Sch.Bip. | 0.5001 | 0.3253 | 0.3645 | 0.8053 | 0.6956 | 0.5382 |

| Angelica amurensis Schischk. | 0.4244 | 0.2477 | 0.4701 | 0.6709 | 0.4193 | 0.4465 |

| Angelica gigas Nakai | 0.3295 | 0.2535 | 0.2559 | 0.6213 | 0.7163 | 0.4353 |

| Anthriscus sylvestris (L.) Hoffm. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3171 | 0.2359 | 0.2192 |

| Aralia elata (Miq.) Seem. | 0.4947 | 0.4241 | 0.6421 | 0.6679 | 0.3174 | 0.5092 |

| Arisaema amurense Maxim. | 0.2062 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.3700 | 0.2752 |

| Arisaema peninsulae Nakai | 0.2339 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3274 | 0.3456 | 0.2614 |

| Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus (Maxim.) H. Hara | 0.6377 | 0.6558 | 0.5829 | 0.5185 | 0.4685 | 0.5727 |

| Asarum sieboldii Miq. | 0.5411 | 0.5381 | 0.8826 | 0.8952 | 0.6440 | 0.7002 |

| Asplenium yokoscense (Franch. & Sav.) H.Christ | 0.4049 | 0.2115 | 0.3624 | 0.8239 | 0.6195 | 0.4844 |

| Aster scaber Thunb. | 0.5762 | 0.4822 | 0.6155 | 0.6368 | 0.3750 | 0.5371 |

| Astilbe rubra Hook.f. & Thomson | 0.5751 | 0.5410 | 0.5410 | 0.7512 | 0.7401 | 0.6297 |

| Athyrium brevifrons Kodama ex Nakai | 0.2404 | 0.8458 | 0.6476 | 0.4577 | 0.6951 | 0.5773 |

| Athyrium niponicum (Mett.) Hance | 0.3673 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.7200 | 0.3750 | 0.4525 |

| Berberis amurensis var. brevifolia Nakai | 0.3737 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.5232 | 0.2400 | 0.3874 |

| Betula costata Trautv. | 0.2822 | 0.3951 | 0.2000 | 0.3340 | 0.2088 | 0.2840 |

| Betula davurica Pall. | 0.2125 | 0.2974 | 0.2974 | 0.5324 | 0.3328 | 0.3345 |

| Betula ermanii Cham. | 0.7720 | 0.4972 | 0.7275 | 0.8812 | 0.7288 | 0.7214 |

| Betula platyphylla var. japonica (Miq.) H. Hara | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3028 | 0.3012 | 0.2294 |

| Betula schmidtii Regel | 0.1429 | 0.2830 | 0.2830 | 0.2830 | 0.1769 | 0.2338 |

| Bistorta manshuriensis (Petrov ex Kom.) Kom. | 0.2407 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3370 | 0.2106 | 0.2377 |

| Calamagrostis arundinacea (L.) Roth | 0.5561 | 0.4203 | 0.4645 | 0.8610 | 0.8218 | 0.6247 |

| Cardamine komarovii Nakai | 0.1429 | 0.5556 | 0.5556 | 0.7143 | 0.2404 | 0.4417 |

| Cardamine leucantha (Tausch) O.E.Schulz | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2386 |

| Carex biwensis Franch. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2386 |

| Carex erythrobasis H.Lév. & Vaniot | 0.3136 | 0.5651 | 0.2915 | 0.5525 | 0.5679 | 0.4581 |

| Carex glabrescens Ohwi | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.1736 |

| Carex hakonensis Franch. & Sav. | 0.5190 | 0.5685 | 0.5685 | 0.5310 | 0.3566 | 0.5087 |

| Carex humilis var. nana (H.Lév. & Vaniot) Ohwi | 0.5708 | 0.4575 | 0.7294 | 0.4922 | 0.5746 | 0.5649 |

| Carex lanceolata Boott | 0.5135 | 0.3155 | 0.5780 | 0.8294 | 0.2812 | 0.5035 |

| Carex okamotoi Ohwi | 0.2056 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.6939 | 0.3745 | 0.3348 |

| Carex siderosticta Hance | 0.2676 | 0.3567 | 0.3625 | 0.6276 | 0.6413 | 0.4511 |

| Caulophyllum robustum Maxim. | 0.2857 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2671 |

| Chrysosplenium flagelliferum F.Schmidt | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3621 | 0.2210 |

| Cimicifuga dahurica (Turcz. ex Fisch. & C.A.Mey.) Maxim. | 0.3155 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.6055 | 0.6106 | 0.3863 |

| Cimicifuga simplex (DC.) Turcz. | 0.1429 | 0.3340 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.2004 |

| Circaea alpina L. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.5155 | 0.3222 | 0.2761 |

| Clematis fusca var. violacea Maxim. | 0.3452 | 0.3951 | 0.3951 | 0.3951 | 0.2469 | 0.3555 |

| Clematis koreana Kom. | 0.1977 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.5686 | 0.4820 | 0.3296 |

| Clintonia udensis Trautv. & C.A.Mey. | 0.3632 | 0.5168 | 0.4404 | 0.7506 | 0.6750 | 0.5492 |

| Cornus controversa Hemsl. | 0.1429 | 0.3514 | 0.3514 | 0.5070 | 0.2394 | 0.3184 |

| Corylus heterophylla Fisch. ex Trautv. | 0.2163 | 0.4820 | 0.4820 | 0.4820 | 0.1892 | 0.3703 |

| Corylus sieboldiana var. mandshurica (Maxim. & Rupr.) | 0.2657 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3797 | 0.5552 | 0.3201 |

| Cymopterus melanotilingia (H.Boissieu) C.Y.Yoon | 0.5352 | 0.3951 | 0.5686 | 0.8695 | 0.5091 | 0.5755 |

| Deutzia glabrata Kom. | 0.2740 | 0.2883 | 0.2883 | 0.5640 | 0.6025 | 0.4034 |

| Deutzia parviflora Bunge | 0.2723 | 0.2000 | 0.3812 | 0.3812 | 0.2383 | 0.2946 |

| Diarrhena fauriei (Hack.) Ohwi | 0.2723 | 0.3812 | 0.3812 | 0.3812 | 0.2383 | 0.3308 |

| Diarrhena mandshurica Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.5684 | 0.2088 | 0.2640 |

| Disporum smilacinum A.Gray | 0.4861 | 0.3836 | 0.5893 | 0.4836 | 0.4253 | 0.4736 |

| Disporum viridescens (Maxim.) Nakai | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.3471 |

| Dryopteris chinensis (Baker) Koidz. | 0.4060 | 0.3951 | 0.5685 | 0.2000 | 0.2469 | 0.3633 |

| Dryopteris crassirhizoma Nakai | 0.4039 | 0.5375 | 0.5402 | 0.6442 | 0.8201 | 0.5892 |

| Dryopteris expansa (C.Presl) Fraser-Jenk. & Jermy | 0.4433 | 0.6492 | 0.6102 | 0.8299 | 0.8398 | 0.6745 |

| Eleutherococcus senticosus (Rupr. & Maxim.) Maxim. | 0.2820 | 0.2621 | 0.2000 | 0.4077 | 0.2956 | 0.2895 |

| Epilobium angustifolium L. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.1736 |

| Equisetum hyemale L. | 0.2336 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4891 | 0.5294 | 0.3304 |

| Euonymus macropterus Rupr. | 0.6096 | 0.6037 | 0.6617 | 0.5648 | 0.7545 | 0.6389 |

| Euonymus oxyphyllus Miq. | 0.3333 | 0.3379 | 0.3379 | 0.3920 | 0.3224 | 0.3447 |

| Euonymus pauciflorus Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3774 | 0.3621 | 0.2565 |

| Euonymus sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) Maxim. | 0.2682 | 0.4977 | 0.5555 | 0.4468 | 0.3472 | 0.4231 |

| Filipendula glaberrima Nakai | 0.4622 | 0.5253 | 0.5253 | 0.5285 | 0.5873 | 0.5257 |

| Fraxinus rhynchophylla Hance | 0.3774 | 0.5440 | 0.5440 | 0.5173 | 0.4327 | 0.4831 |

| Fraxinus sieboldiana Blume | 0.4412 | 0.2000 | 0.2600 | 0.7338 | 0.6768 | 0.4624 |

| Galium kamtschaticum Steller ex (Roem. & Schult.) | 0.1429 | 0.4000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2500 | 0.2386 |

| Gentiana triflora var. japonica (Kusn.) H. Hara | 0.2286 | 0.3200 | 0.3200 | 0.3200 | 0.5000 | 0.3377 |

| Geranium koreanum Kom. | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.3471 |

| Hemerocallis hakuunensis Nakai | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2826 | 0.2613 | 0.2173 |

| Hosta capitata (Koidz.) Nakai | 0.3507 | 0.2000 | 0.3951 | 0.4910 | 0.2470 | 0.3368 |

| Hosta plantaginea (Lam.) Asch. | 0.1429 | 0.3340 | 0.2000 | 0.3340 | 0.3553 | 0.2732 |

| Hydrangea serrata f. acuminata (Siebold & Zucc.) E.H.Wilson | 0.3280 | 0.3995 | 0.4592 | 0.2352 | 0.3512 | 0.3546 |

| Hydrocotyle sibthorpioides Lam. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3812 | 0.2382 | 0.2325 |

| Hypericum ascyron L. | 0.2857 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2671 |

| Impatiens nolitangere L. | 0.2101 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3600 | 0.4767 | 0.2894 |

| Isodon excisus (Maxim.) Kudo | 0.3321 | 0.2231 | 0.2231 | 0.7402 | 0.6529 | 0.4343 |

| Juglans mandshurica Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.2536 |

| Kalopanax septemlobus (Thunb.) Koidz. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2386 |

| Larix olgensis var. koreana (Nakai) Nakai | 0.2723 | 0.3812 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2382 | 0.2583 |

| Lepisorus ussuriensis (Regel & Maack) Ching | 0.5054 | 0.6760 | 0.8921 | 0.6043 | 0.8108 | 0.6977 |

| Ligularia fischeri (Ledeb.) Turcz. | 0.5812 | 0.5502 | 0.6168 | 0.6845 | 0.5974 | 0.6060 |

| Lilium distichum Nakai ex Kamib. | 0.4083 | 0.3802 | 0.3802 | 0.5716 | 0.3573 | 0.4195 |

| Lilium tsingtauense Gilg | 0.2339 | 0.3274 | 0.3274 | 0.5529 | 0.1250 | 0.3133 |

| Lonicera caerulea var. edulis Turcz. ex Herder | 0.1429 | 0.3456 | 0.2000 | 0.3456 | 0.2160 | 0.2500 |

| Lonicera chrysantha Turcz. | 0.3982 | 0.2999 | 0.2999 | 0.6506 | 0.7263 | 0.4750 |

| Lonicera maackii (Rupr.) Maxim. | 0.2463 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2155 | 0.2124 |

| Lonicera sachalinensis (F.Schmidt) Nakai | 0.2302 | 0.3223 | 0.3223 | 0.3486 | 0.5614 | 0.3570 |

| Lonicera tatarinowii var. leptantha (Rehder) Nakai | 0.1429 | 0.2912 | 0.2000 | 0.2722 | 0.4045 | 0.2622 |

| Lychnis cognata Maxim. | 0.4286 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3600 | 0.3750 | 0.3127 |

| Lycopodium chinense H.Christ | 0.2368 | 0.4954 | 0.2972 | 0.5843 | 0.5630 | 0.4353 |

| Lycopodium obscurum L. | 0.2021 | 0.3618 | 0.2829 | 0.5528 | 0.4579 | 0.3715 |

| Lycopodium serratum Thunb. | 0.2923 | 0.6467 | 0.7273 | 0.6845 | 0.6056 | 0.5913 |

| Magnolia sieboldii K.Koch | 0.3708 | 0.3328 | 0.3382 | 0.5491 | 0.5104 | 0.4202 |

| Maianthemum bifolium (L.) F.W.Schmidt | 0.2482 | 0.3474 | 0.3474 | 0.3474 | 0.4765 | 0.3534 |

| Maianthemum dilatatum (Wood) A.Nelson & J.F.Macbr. | 0.1637 | 0.3969 | 0.2000 | 0.5218 | 0.5680 | 0.3701 |

| Malus baccata (L.) Borkh. | 0.2723 | 0.3812 | 0.3812 | 0.3812 | 0.2382 | 0.3308 |

| Meehania urticifolia (Miq.) Makino | 0.2740 | 0.4657 | 0.4657 | 0.7925 | 0.7707 | 0.5537 |

| Oplopanax elatus (Nakai) Nakai | 0.2405 | 0.3367 | 0.3367 | 0.7484 | 0.4458 | 0.4216 |

| Osmunda cinnamomea var. forkiensis Copel. | 0.2772 | 0.3881 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3371 | 0.2805 |

| Ostericum grosseserratum (Maxim.) Kitag. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.5104 | 0.4301 | 0.2967 |

| Oxalis acetosella L. | 0.2175 | 0.7986 | 0.4526 | 0.5912 | 0.6992 | 0.5518 |

| Oxalis corniculata L. | 0.1429 | 0.3812 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2383 | 0.2325 |

| Paeonia japonica (Makino) Miyabe & Takeda | 0.2571 | 0.3600 | 0.3600 | 0.3600 | 0.3750 | 0.3424 |

| Parasenecio adenostyloides (Franch. & Sav. ex Maxim.) H.Koyama | 0.1798 | 0.3513 | 0.2456 | 0.5639 | 0.4906 | 0.3663 |

| Parasenecio auriculata var. kamtschatica (Maxim.) H.Koyama | 0.2608 | 0.4296 | 0.4296 | 0.4391 | 0.5727 | 0.4263 |

| Parasenecio auriculata var. matsumurana Nakai | 0.3567 | 0.3858 | 0.4486 | 0.5101 | 0.3188 | 0.4040 |

| Paris verticillata M.Bieb. | 0.4595 | 0.3701 | 0.3701 | 0.7476 | 0.5360 | 0.4966 |

| Patrinia saniculaefolia Hemsl. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2386 |

| Pedicularis resupinata L. | 0.6221 | 0.4593 | 0.4995 | 0.6834 | 0.7320 | 0.5993 |

| Philadelphus tenuifolius Rupr. & Maxim. | 0.3506 | 0.4194 | 0.4194 | 0.9324 | 0.4525 | 0.5149 |

| Picea jezoensis (Siebold & Zucc.) Carrière | 0.5357 | 0.7221 | 0.7366 | 0.8844 | 0.8267 | 0.7411 |

| Pilea mongolica Wedd. | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.3471 |

| Pinus densiflora Siebold & Zucc. | 0.2265 | 0.3171 | 0.3171 | 0.3171 | 0.1982 | 0.2752 |

| Pinus koraiensis Siebold & Zucc. | 0.4197 | 0.4702 | 0.5293 | 0.8479 | 0.8306 | 0.6195 |

| Polygonatum odoratum var. pluriflorum (Miq.) Ohwi | 0.2131 | 0.2983 | 0.2983 | 0.2983 | 0.4611 | 0.3138 |

| Polystichum braunii (Spenn.) Fee | 0.1429 | 0.2601 | 0.2601 | 0.3982 | 0.3388 | 0.2800 |

| Polystichum tripteron (Kunze) C.Presl | 0.3690 | 0.4297 | 0.4497 | 0.7268 | 0.7183 | 0.5387 |

| Populus maximowiczii A.Henry | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.3471 |

| Potentilla fragarioides var. major Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.3449 | 0.3449 | 0.3449 | 0.2155 | 0.2786 |

| Primula jesoana Miq. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.1736 |

| Prunus maximowiczii Rupr. | 0.2844 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3982 | 0.3451 | 0.2856 |

| Prunus padus L. | 0.2524 | 0.2490 | 0.2490 | 0.6954 | 0.8644 | 0.4620 |

| Prunus sargentii Rehder | 0.2266 | 0.3172 | 0.3172 | 0.3172 | 0.1982 | 0.2753 |

| Pseudostellaria heterophylla (Miq.) Pax ex Pax & Hoffm. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.1736 |

| Pseudostellaria palibiniana (Takeda) Ohwi | 0.2725 | 0.3048 | 0.3048 | 0.6185 | 0.5527 | 0.4106 |

| Pseudostellaria setulosa Ohwi | 0.3092 | 0.3821 | 0.3821 | 0.5302 | 0.4278 | 0.4063 |

| Pyrola renifolia Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4910 | 0.3069 | 0.2681 |

| Quercus mongolica Fisch. ex Ledeb. | 0.4982 | 0.5348 | 0.7782 | 0.8367 | 0.5108 | 0.6317 |

| Rhododendron mucronulatum var. ciliatum Nakai | 0.5280 | 0.2886 | 0.3532 | 0.9478 | 0.6356 | 0.5506 |

| Rhododendron schlippenbachii Maxim. | 0.7110 | 0.3748 | 0.5172 | 0.9672 | 0.7425 | 0.6625 |

| Rhododendron tschonoskii Maxim. | 0.4209 | 0.2000 | 0.3664 | 0.4504 | 0.3246 | 0.3525 |

| Ribes mandshuricum (Maxim.) Kom. | 0.4083 | 0.3802 | 0.3802 | 0.3802 | 0.3573 | 0.3812 |

| Ribes maximowiczianum Kom. | 0.5241 | 0.4558 | 0.5432 | 0.5498 | 0.5126 | 0.5171 |

| Rodgersia podophylla A.Gray | 0.3456 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.6989 | 0.3943 | 0.3678 |

| Rosa davurica Pall. | 0.2766 | 0.3990 | 0.3990 | 0.2517 | 0.2494 | 0.3151 |

| Rosa suavis Willd. | 0.3412 | 0.4040 | 0.3675 | 0.8889 | 0.7396 | 0.5482 |

| Rubia akane Nakai | 0.2920 | 0.3662 | 0.3662 | 0.5598 | 0.2555 | 0.3680 |

| Rubia chinensis Regel & Maack | 0.2206 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1930 | 0.2027 |

| Rubia cordifolia var. pratensis Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.1250 | 0.1736 |

| Rubus crataegifolius Bunge | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.3471 |

| Rubus idaeus var. microphyllus Turcz. | 0.1429 | 0.3028 | 0.2000 | 0.4820 | 0.4747 | 0.3205 |

| Salix caprea L. | 0.5149 | 0.3581 | 0.5453 | 0.5453 | 0.2531 | 0.4433 |

| Sambucus sieboldiana var. miquelii (Nakai) Hara | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3812 | 0.2383 | 0.2325 |

| Sambucus williamsii var. coreana (Nakai) Nakai | 0.6465 | 0.4043 | 0.6774 | 0.6108 | 0.4971 | 0.5672 |

| Sasa borealis (Hack.) Makino | 0.2206 | 0.2000 | 0.2363 | 0.3989 | 0.2432 | 0.2598 |

| Saussurea gracilis Maxim. | 0.4791 | 0.2324 | 0.2324 | 0.7460 | 0.4339 | 0.4248 |

| Saussurea grandifolia Maxim. | 0.4591 | 0.6427 | 0.5334 | 0.5334 | 0.3334 | 0.5004 |

| Saxifraga fortunei var. incisolobata (Engl. & Irmsch.) Nakai | 0.2986 | 0.5322 | 0.5322 | 0.2826 | 0.2612 | 0.3814 |

| Saxifraga oblongifolia Nakai | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.1250 | 0.2136 |

| Saxifraga octopetala Nakai | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4000 | 0.2500 | 0.2386 |

| Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. | 0.3810 | 0.3200 | 0.3200 | 0.4000 | 0.3333 | 0.3509 |

| Sedum polytrichoides Hemsl. | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.2000 | 0.2500 | 0.3071 |

| Smilacina japonica A.Gray | 0.2774 | 0.5764 | 0.5764 | 0.5007 | 0.3966 | 0.4655 |

| Solidago virgaurea subsp. asiatica Kitam. ex Hara | 0.7979 | 0.3458 | 0.4939 | 0.8644 | 0.7344 | 0.6473 |

| Sorbus alnifolia (Siebold & Zucc.) K.Koch | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3600 | 0.1250 | 0.2056 |

| Sorbus commixta Hedl. | 0.4706 | 0.5892 | 0.6250 | 0.8114 | 0.8250 | 0.6642 |

| Spiraea chamaedryfolia L. | 0.2286 | 0.3200 | 0.3200 | 0.3200 | 0.5000 | 0.3377 |

| Spiraea fritschiana C.K.Schneid. | 0.2131 | 0.2983 | 0.2983 | 0.3891 | 0.2355 | 0.2868 |

| Spodipogon cotulifer (Thunb.) Hack. | 0.2286 | 0.2000 | 0.3200 | 0.3200 | 0.5000 | 0.3137 |

| Streptopus amplexifolius var. papillatus Ohwi | 0.1429 | 0.3340 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2088 | 0.2171 |

| Streptopus koreanus (Kom.) Ohwi | 0.1429 | 0.3787 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.4479 | 0.2739 |

| Streptopus ovalis (Ohwi) F.T.Wang & Y.C.Tang | 0.2571 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.6000 | 0.3750 | 0.3264 |

| Symplocos chinensis f. pilosa (Nakai) Ohwi | 0.3902 | 0.3999 | 0.4704 | 0.7879 | 0.4843 | 0.5065 |

| Synurus deltoides (Aiton) Nakai | 0.5387 | 0.2689 | 0.2689 | 0.6805 | 0.5690 | 0.4652 |

| Syringa patula (Palib.) Nakai | 0.3301 | 0.2638 | 0.2638 | 0.3359 | 0.2249 | 0.2837 |

| Taxus cuspidata Siebold & Zucc. | 0.4287 | 0.3665 | 0.3824 | 0.7177 | 0.7628 | 0.5316 |

| Thalictrum aquilegifolium var. sibiricum Regel & Tiling | 0.2183 | 0.3057 | 0.3057 | 0.3057 | 0.1911 | 0.2653 |

| Thalictrum filamentosum var. tenerum (Huth) Ohwi | 0.1978 | 0.3948 | 0.3255 | 0.3255 | 0.2868 | 0.3061 |

| Thelypteris japonica (Baker) Ching | 0.2857 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.3333 | 0.3638 |

| Thelypteris phegopteris (L.) Sloss. | 0.6597 | 0.5766 | 0.5351 | 0.8358 | 0.7782 | 0.6771 |

| Thuja koraiensis Nakai | 0.1947 | 0.2726 | 0.2726 | 0.3554 | 0.3136 | 0.2818 |

| Tilia amurensis Rupr. | 0.2034 | 0.5254 | 0.4835 | 0.6196 | 0.5732 | 0.4810 |

| Trillium kamtschaticum Pall. ex Pursh | 0.1429 | 0.4996 | 0.4996 | 0.5331 | 0.4579 | 0.4266 |

| Trillium tschonoskii Maxim. | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2332 | 0.1952 |

| Tripterygium regelii Sprague & Takeda | 0.7049 | 0.4501 | 0.5921 | 0.8652 | 0.8255 | 0.6876 |

| Ulmus laciniata (Trautv.) Mayr | 0.2445 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.3689 | 0.1590 | 0.2345 |

| Vaccinium hirtum var. koreanum (Nakai) Kitam. | 0.4794 | 0.5267 | 0.5267 | 0.4585 | 0.3246 | 0.4632 |

| Veratrum maackii var. japonicum (Baker) T.Schmizu | 0.1429 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.4000 | 0.1250 | 0.2936 |

| Veratrum oxysepalum Turcz. | 0.2822 | 0.3951 | 0.3951 | 0.5685 | 0.3553 | 0.3992 |

| Viburnum opulus var. calvescens (Rehder) H. Hara | 0.1997 | 0.2795 | 0.2795 | 0.2795 | 0.1747 | 0.2426 |

| Viola selkirkii Pursh ex Goldie | 0.3487 | 0.5919 | 0.5919 | 0.5222 | 0.3264 | 0.4762 |

| Viola verecunda A.Gray | 0.1429 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2000 | 0.2500 | 0.1986 |

| Weigela florida (Bunge) A.DC. | 0.7171 | 0.4287 | 0.5220 | 0.6481 | 0.6917 | 0.6015 |

| Woodsia polystichoides D.C.Eaton | 0.3810 | 0.2000 | 0.3200 | 0.5333 | 0.3333 | 0.3535 |

References

- Rapoport, E.H. Areography: Geographical Strategies of Species; Elsevier: London, UK, 2013; Volume 1, pp. 225–230. ISBN 9780080289144. [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker, R.H.; Levin, S.A.; Root, R.B. Niche, Habitat, and Ecotope. Am. Nat. 1973, 107, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, L.; Homeier, J.; Kessler, M.; Abrahamczyk, S.; Lehnert, M.; Krömer, T.; Kluge, J. Diversity patterns of ferns along elevational gradients in andean tropical forests. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2015, 8, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.C. The elevational gradient in altitudinal range: An extension of Rapoport’s latitudinal rule to altitude. Am. Nat. 1992, 140, 893–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, B.A.; Diniz-Filho, J.A.F.; Jaramillo, C.A.; Soeller, S.A. Post-Eocene climate change, niche conservatism, and the latitudinal diversity gradient of New World birds. J. Biogeogr. 2006, 33, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manor, A.; Shnerb, N.M. Facilitation, competition, and vegetation patchiness: From scale free distribution to patterns. J. Theor. Biol. 2008, 253, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeocheon Ecological Research Association. Modern Ecological Experiment; Gyomunsa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005; pp. 166–179. ISBN 9788936307516. [Google Scholar]

- Germino, M.J.; Smith, W.K.; Resor, A.C. Conifer seedling distribution and survival in an alpine-treeline ecotone. Plant Ecol. 2002, 162, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, A.; Mizumachi, E.; Osono, T.; Doi, Y. Substrate-associated seedling recruitment and establishment of major conifer species in an old-growth subalpine forest in central Japan. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 196, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, U.; Brang, P. Microsite patterns of conifer seedling establishment and growth in a mixed stand in the southern Alps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 210, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, S.F.; Mori, A. Structural characteristics of Abies mariesii saplings in a snowy subalpine parkland in central Japan. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Han, A.R.; Lee, S.K.; Suh, G.U.; Park, Y.; Park, P.S. Wind and topography influence the crown growth of Picea jezoensis in a subalpine forest on Mt. Deogyu, Korea. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2012, 166–167, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Lee, H.Y.; Lee, N.Y.; Lee, H.; Song, J.Y. Survey on the distribution of Evergreen Conifers in the Major national Park—A case Study on Seoraksan, Odaesan, Taebaeksan, Sobaaeksan, Doegyusan, Jirisan National Park. J. Nat. Park. Res. 2019, 10, 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, W.S. Species composition and distribution of Korean Alpine Plants. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2002, 37, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- The Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Nakagawa, M.; Kurahashi, A.; Hogetsu, T. The regeneration characteristics of Picea jezoensis and Abies sachalinensis on cut stumps in the sub-boreal forests of Hokkaido Tokyo University Forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 180, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, M.; Yoshimaru, H.; Saito, H.; Katsuki, T.; Kawahara, T.; Kitamura, K.; Shi, F.; Sabirov, R.; Kaji, M. Range-wide genetic structure in a north-east Asian spruce (Picea jezoensis) determined using nuclear microsatellite markers. J. Biogeogr. 2009, 36, 996–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J. Generality and Specificity of Landforms of the Korean Peninsula, and Its Sustainability. J. Korean Geogr. Soc. 2014, 49, 656–674. [Google Scholar]

- Park, G.E.; Kim, E.S.; Jung, S.C.; Yun, C.W.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.D.; Kim, J.B.; Lim, J.H. Distribution and Stand Dynamics of Subalpine Conifer Species (Abies nephrolepis, A. koreana, and Picea jezoensis) in Baekdudaegan Protected Area. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2022, 111, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Byeon, J.G.; Heo, T.I.; Cheon, K.; Yang, J.C.; Oh, S.H. Comparison of species composition among Picea jezoensis (Siebold & Zucc.) carrière forests in Northeast Asia (from China to South Korea). J. Asia-Pac. Biodivers. 2023, 16, 272–281. [Google Scholar]

- Odion, D.C.; Sarr, D.A. Managing disturbance regimes to maintain diversity in forested ecosystems of the Pacific Northwest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 246, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, T.A.; Sullivan, J.E. The Selection and Design of Multiple Species Preserves. Environ. Manag. 2000, 26, S37–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrows, C.W.; Swartz, M.B.; Hodges, W.L.; Allen, M.F.; Rotenberry, J.T.; Li, B.L.; Scott, T.A.; Chen, X. A Framework for Monitoring Multiple-species Conservation Plans. J. Wildl. Manag. 2005, 69, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Services of Climatic Data Portal of Korea Meteorological Administration. Available online: https://data.kma.go.kr/cmmn/main.do (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Pflanzensoziologie, Grundzfige der Vegetationskunde, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1965; pp. 7–16. ISBN 9783540034789. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.B. Coloured Flora of Korea; Hyangmoonsa: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 1–916. ISBN 9788971871959. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Fern Society. Ferns and Fern Allies of Korea; Geobook: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2005; pp. 1–399. ISBN 9788995504925. [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge System of National Species in Korea. Available online: http://www.nature.go.kr/kpni/ (accessed on 16 August 2022).

- Newton, A.C. Forest Ecology and Conservation: A Handbook of Techniques; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 85–146. ISBN 9780198567455. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, A. Nonparametric Estimation of the Number of Class in Population. Scand. J. Stat. 1984, 11, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Levins, R. Evolution in Changing Environments; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1968; pp. 2–120. ISBN 9780691079592. [Google Scholar]

- PC-Ord Specifications. Available online: https://www.wildblueberrymedia.net/pc-ord-specifications/ (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Cornwell, W.K.; Schwilk, D.W.; Ackerly, D.D. A trait-based test for habitat filtering: Convex hull volume. Ecology 2006, 87, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.T.; Kim, H.J. Studies on the Seed Characteristics and Viabilities of Six Acer species in Relation to Natural Regeneration in Korea. Korea J. Environ. Ecol. 2011, 25, 358–364. [Google Scholar]

- Edward, E.C.C.; Richard, T.B. Secondary Succession, Gap Dynamics, and Community Structure in a Southern Appalachian Cove Forest. Ecology 1989, 70, 728–735. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, J.R. Gap phase replacement in maple-basswood forest. Ecology 1956, 37, 598–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmins, J.P. Forest Ecology: A Foundation for Sustainable Management; Prentice-Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997; p. 596. ISBN 9780023640711. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing, D.H. Vascular Epiphytes: General Biology and Related Biota; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 210–271. ISBN 9780521048958. [Google Scholar]

- Zotz, G.; Hietz, P. The physiological ecology of vascular epiphytes: Current knowledge, open questions. J. Exp. Bot. 2001, 52, 2067–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadkarni, N.M.; Matelson, T.J. Biomass and nutrient dynamics of epiphytic litterfall in a neotropical cloud forest, Costa Rica. Biotropica 1991, 23, 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, K.U.; Green, P.S. The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants; Kubitzki, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 1–14. ISBN 9780947643430. [Google Scholar]

- Page, C.N. Ecological strategies in fern evolution: A neopteridological overview. Bot. Rev. 2002, 68, 345–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.R.; Pryer, K.M.; Schuettpelz, E.; Korall, P.; Schneider, H.; Wolf, P.G. A classification for extant ferns. Taxon 2006, 55, 705–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams-Linera, G.; Palacios-Rios, M.; Hernández-Gómez, R. Fern richness, tree species surrogacy, and fragment complementarity in a Mexican tropical montane cloud forest. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, Y.G. Classification and Assessment of Plant Communities. World Science: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2006; pp. 1–240. ISBN 9788958810605. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Heo, T.I.; Byeon, J.G.; Cheon, K. Study on Plant Indicator Species of Picea jezoensis (Siebold & Zucc.) Carrière Forest by Topographic Characters—From China (Baekdu-san) to South Korea. J. Environ. Impact Assess. 2022, 31, 388–408. [Google Scholar]

- Langford, A.N.; Buell, M.F. Integration, identity, and stability in the plant association. Adv. Ecol. Res. 1969, 6, 83–135. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Gong, Z.; Li, W. Niches and Interspecifc Associations of Dominant Populations in Three Changed Stages of Natural Secondary Forests on Loess Plateau, P.R. China. Nature 2017, 7, 6604. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, S.T.A. Population patterns through twenty years of old-field succession. Vegetatio 1982, 19, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C.D.; Larson, B.C. Forest Stand Dynamics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 9–38. ISBN 9780070478299. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.Q.; Matsui, T.; Ohashi, H.; Dong, Y.F.; Momohara, A.; Herrando-Moraira, S.; Qian, S.; Yang, Y.; Ohsawa, M.; Luu, H.T.; et al. Identifying long-term stable refugia for relict plant species in East Asia. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.Q.; Ohsawa, M. Tertiary relic deciduous forests on a subtropical mountain, Mt. Emei, Sichuan, China. Folia Geobot. 2002, 37, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulch, A.; Chamberlain, C.P. The rise and growth of Tibet. Nature 2006, 439, 670–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C.Q.; Yang, Y.; Ohsawa, M.; Momohara, A.; Hara, M.; Cheng, S.; Fan, S. Population structure of relict Metasequoia glyptostroboides and its habitat fragmentation and degradation in south-central China. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Y.; Tang, C.Q.; Wu, Z.L.; Wang, H.C.; Ohsawa, M.; Yan, K. Forest structure and regeneration of the Tertiary relict Taiwania cryptomerioides in the Gaoligong Mountains, Yunnan, southwestern China. Phytocoenologia 2015, 45, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzedakis, P.C.; Lawson, I.T.; Frogley, M.R.; Hewitt, G.M.; Preece, R.C. Buffered tree population changes in a Quaternary refugium: Evolutionary implications. Science 2002, 297, 2044–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, H.J.B.; Willis, K.J. Alpines, trees, and refugia in Europe. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2008, 1, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppel, G.; Van Niel, K.P.; Wardell-Johnson, G.W.; Yates, C.J.; Byrne, M.; Mucina, L.; Schut, A.G.; Hopper, S.D.; Franklin, S.E. Refugia: Identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012, 21, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, T.L.; Daly, C.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Dulen, D.M.; Ebersole, J.L.; Jackson, S.T.; Lundquist, J.D.; Millar, C.I.; Maher, S.P.; Monahan, W.B.; et al. Managing climate change refugia for climate adaptation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.; Noss, R. Viewpoint: Part of a special issue on endemics hotspots, endemism hotspots are linked to stable climatic refugia. Ann. Bot. 2017, 119, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).