Immunological Profile in Atypical Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report Highlighting the Diagnostic Utility of Cytokine Analysis by qRT-PCR

Abstract

1. Introduction

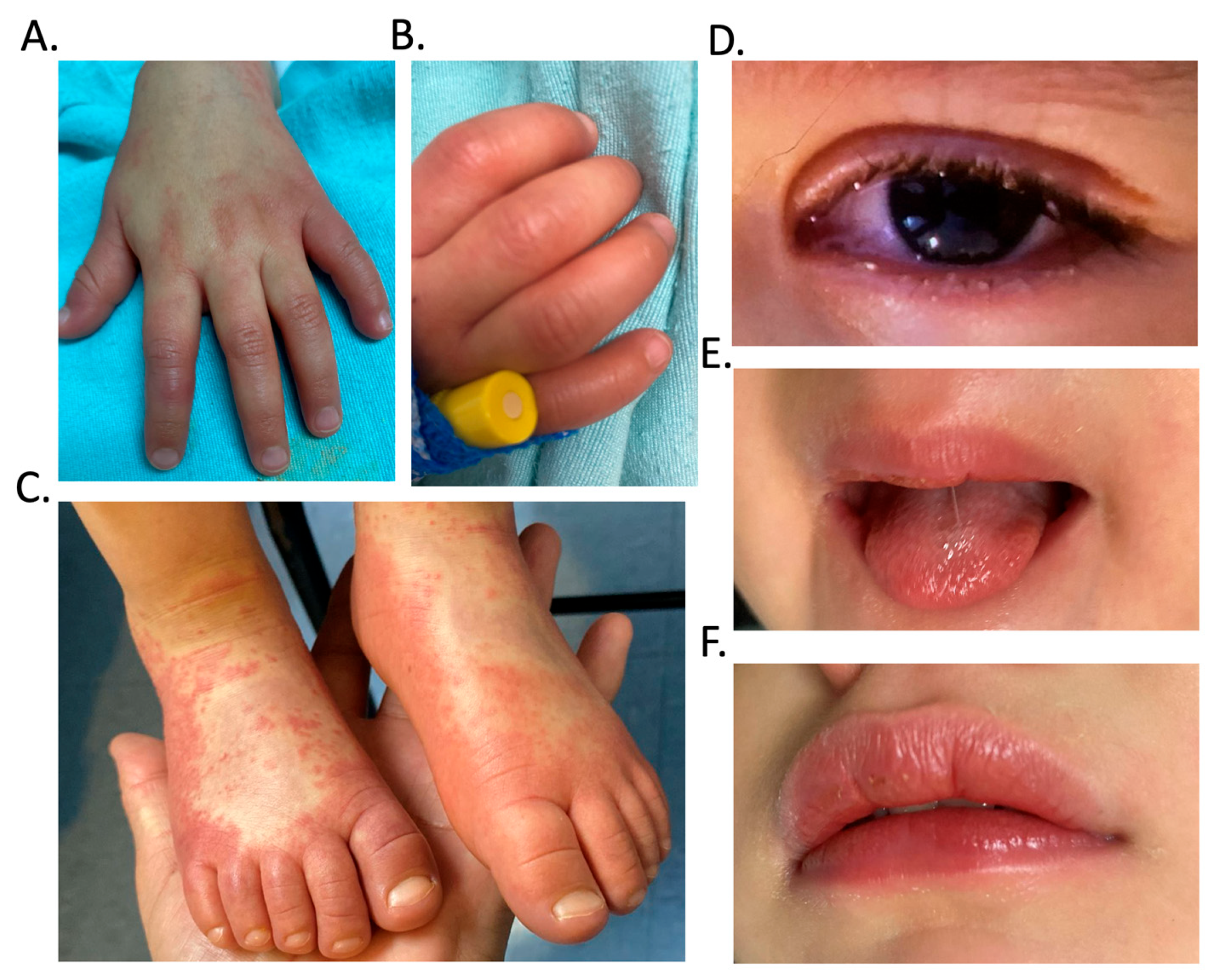

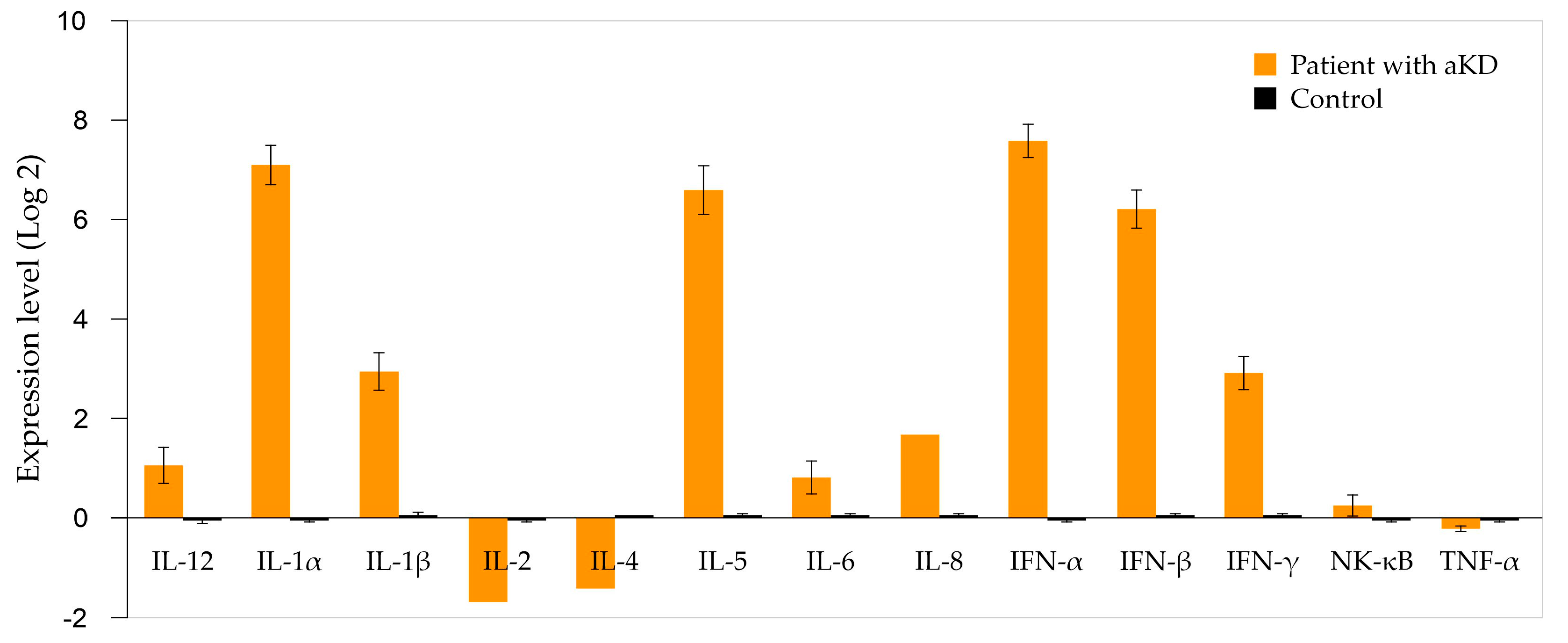

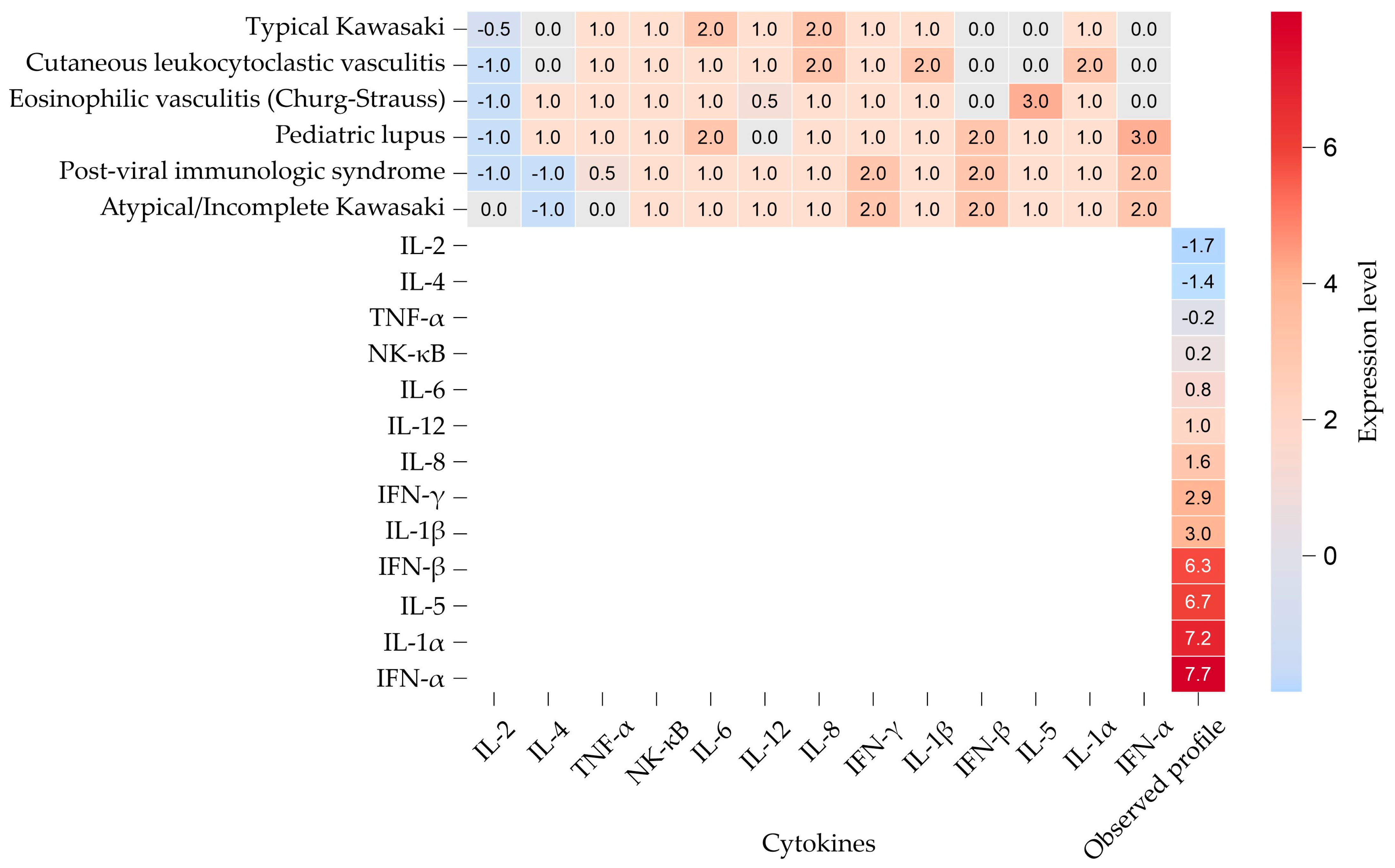

2. Case Description

Outcome

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ASA | acetylsalicylic acid |

| BH | hematological biometrics |

| CA | coronary arteries |

| c-ANCA | Cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| DAMPs | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| ESR | erythrocyte sedimentation rate |

| Hb | Hemoglobin |

| HD | Hospital discharge |

| HS | Hospital stays |

| IFN-α or INF-a | Interferon alpha |

| IFN-β or INF-b | Interferon beta |

| IFN-γ or INF-g | Interferon gamma |

| IGIV | Intravenous immunoglobulin |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IL-1α | Interleukin 1-alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 beta |

| KD | Kawasaki disease |

| KDSS | Kawasaki disease shock syndrome |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| MIS-C | Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children |

| NF-κB | Factor nuclear kappa B |

| NETs | Neutrophil extracellular trap |

| p-ANCA | Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies |

| PAMPs | pathogen-associated molecular pattern |

| Plt | Platelets |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RDW-CV | Red Cell Distribution Width Coefficient of Variation |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

References

- Jone, P.N.; Tremoulet, A.; Choueiter, N.; Dominguez, S.R.; Harahsheh, A.S.; Mitani, Y.; Zimmerman, M.; Lin, M.T.; Friedman, K.G.; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, E.; et al. Update on Diagnosis and Management of Kawasaki Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 150, e481–e500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Vignesh, P.; Burgner, D. The epidemiology of Kawasaki disease: A global update. Arch. Dis. Child. 2015, 100, 1084–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newburger, J.W.; Takahashi, M.; Burns, J.C. Kawasaki Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1738–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kainth, R.; Shah, P. Kawasaki disease: Origins and evolution. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.C. Diagnosis, Progress, and Treatment Update of Kawasaki Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.C.; Corsello, G. Atypical and incomplete Kawasaki disease. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2015, 41 (Suppl. 2), A45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.J. Diagnosis of incomplete Kawasaki disease. Korean J. Pediatr. 2012, 55, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonobe, T.; Kiyosawa, N.; Tsuchiya, K.; Aso, S.; Imada, Y.; Imai, Y.; Yashiro, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Yanagawa, H. Prevalence of coronary artery abnormality in incomplete Kawasaki disease. Pediatr. Int. 2007, 49, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozois, C.M.; Oswald, E.; Gautier, N.; Serthelon, J.P.; Fairbrother, J.M.; Oswald, I.P. A reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction method to analyze porcine cytokine gene expression. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1997, 58, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berti, R.; Williams, A.J.; Moffett, J.R.; Hale, S.L.; Velarde, L.C.; Elliott, P.J.; Yao, C.; Dave, J.R.; Tortella, F.C. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of inflammatory gene expression associated with ischemia-reperfusion brain injury. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2002, 22, 1068–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, L.; Campbell, M.J.; Wu, E.Y. Multisystemic Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Kawasaki Disease: Parallels in Pathogenesis and Treatment. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2023, 23, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, R.; Wright, V.J.; Habgood-Coote, D.; Shimizu, C.; Huigh, D.; Tremoulet, A.H.; van Keulen, D.; Hoggart, C.J.; Rodriguez-Manzano, J.; Herberg, J.A.; et al. Bridging a diagnostic Kawasaki disease classifier from a microarray platform to a qRT-PCR assay. Pediatr. Res. 2023, 93, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zou, L.; Wu, J.; Guo, L.; Teng, L.; Zheng, R.; Jung, L.K.L.; Lu, M. Kawasaki disease shock syndrome: Clinical characteristics and possible use of IL-6, IL-10 and IFN-gamma as biomarkers for early recognition. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2019, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Ganigara, M.; Galeotti, C.; Burns, J.; Berganza, F.M.; Hayes, D.A.; Singh-Grewal, D.; Bharath, S.; Sajjan, S.; Bayry, J. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and Kawasaki disease: A critical comparison. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2021, 17, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordea, M.A.; Costache, C.; Grama, A.; Florian, A.I.; Lupan, I.; Samasca, G.; Deleanu, D.; Makovicky, P.; Makovicky, P.; Rimarova, K. Cytokine cascade in Kawasaki disease versus Kawasaki-like syndrome. Physiol. Res. 2022, 71, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.B.; Kim, Y.H.; Hyun, M.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, Y.H. T-Helper Cytokine Profiles in Patients with Kawasaki Disease. Korean Circ. J. 2015, 45, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, B.A.; Andersson, U.; Laxer, R.M.; Rose, V.; Silverman, E.D. Evaluation of the cytokine response in Kawasaki disease. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 1995, 14, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Yang, J.; Zu, Y. The T helper type 17/regulatory T cell imbalance in patients with acute Kawasaki disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010, 162, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, H.A. Hematología Práctica: Interpretación del Hemograma y de las Pruebas de Coagulación, AEPap, Ed.; Congreso de Actualización Pediatría: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 507–528. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, Y.G. Valores de Referencia en Pediatría; Universidad Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, A.H. Anemias en la infancia y adolescencia. Clasificación y diagnóstico. Pediatr. Integral 2012, 5, 357–365. [Google Scholar]

- Dossybayeva, K.; Bexeitov, Y.; Mukusheva, Z.; Almukhamedova, Z.; Assylbekova, M.; Abdukhakimova, D.; Rakhimzhanova, M.; Poddighe, D. Analysis of Peripheral Blood Basophils in Pediatric Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.C.; Sunaina, K.; Mark Tiffany, E. The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Doven, S.S.; Tezol, O.; Yesil, E.; Durak, F.; Misirlioglu, M.; Alakaya, M.; Karahan, F.; Killi, I.; Akca, M.; Erdogan, S.; et al. The 2023 Turkiye-Syria earthquakes: Analysis of pediatric victims with crush syndrome and acute kidney Injury. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 2209–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J.W.; Wang, D.; Brady, T.; Tang, O.; Ndumele, C.E.; Coresh, J.; Christenson, R.H.; Selvin, E. Myocardial Injury Thresholds for 4 High-Sensitivity Troponin Assays in a Population-Based Sample of US Children and Adolescents. Circulation 2023, 148, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, T.E. Diagnosis and treatment: Some syndromes, diseases, and conditions associated with abnormal coloration of the urine or diaper: A Clinician’s Viewpoint. Pediatrics 1968, 41, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marutani, K.; Murata, K.; Mizuno, Y.; Onoyama, S.; Hoshina, T.; Yamamura, K.; Furuno, K.; Sakai, Y.; Kishimoto, J.; Kusuhura, K. Respiratory viral infections and Kawasaki disease: A molecular epidemiological analysis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2024, 57, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnier, J.L.; Anderson, M.S.; Heizer, H.R.; Jone, P.-N.; Glodé, M.P.; Dominguez, S.R. Concurrent respiratory viruses and Kawasaki disease. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e609–e614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menikou, S.; Langford, P.R.; Levin, M. Kawasaki disease: The role of immune complexes revisited. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Wu, S.; Cao, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S. Neutrophil-Derived Semaphorin 4D Induces Inflammatory Cytokine Production of Endothelial Cells via Different Plexin Receptors in Kawasaki Disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 6663291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macchia, I.; La Sorsa, V.; Urbani, F.; Moretti, S.; Antonucci, C.; Afferni, C.; Schiavoni, G. Eosinophils as potential biomarkers in respiratory viral infections. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1170035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Li, H.; Lee, M.H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, J.S.; Han, Y.J.; Cho, K.; Ha, B.; Kim, S.J.; Jacob, L. Clinical characteristics and treatments of multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 3342–3350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.-C.; Kuo, H.-C.; Yu, H.-R.; Huang, H.-C.; Chang, J.-C.; Lin, I.-C.; Chen, I.-L. Profile of urinary cytokines in Kawasaki disease: Non-invasive markers. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Yang, H.-W.; Lin, T.-Y.; Yang, K.D. Perspective of immunopathogenesis and immunotherapies for Kawasaki disease. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 697632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadig, P.L.; Joshi, V.; Pilania, R.K.; Kumrah, R.; Kabeerdoss, J.; Sharma, S.; Suri, D.; Rawat, A.; Singh, S. Intravenous immunoglobulin in Kawasaki Disease—Evolution and pathogenic mechanisms. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrindle, B.W.; Rowley, A.H.; Newburger, J.W.; Burns, J.C.; Bolger, A.F.; Gewitz, M.; Baker, A.L.; Jackson, M.A.; Takahashi, M.; Shah, P.B. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: A scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e927–e999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguil, A.; Fargo, M.; Grogan, S. Diagnosis and management of Kawasaki disease. Am. Fam. Physician 2015, 91, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siraj, S.; Parra, C.S.; Jordan, J.; Shah, A.; Amankwah, E.; Fadrowski, J. Clinical Utility of Follow-up Echocardiograms in Uncomplicated Kawasaki Disease. Sci. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H. Diagnosis of coronary artery abnormalities in Kawasaki disease: Recent guidelines and z score systems. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 65, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Graeff, N.; Groot, N.; Ozen, S.; Eleftheriou, D.; Avcin, T.; Bader-Meunier, B.; Dolezalova, P.; Feldman, B.M.; Kone-Paut, I.; Lahdenne, P. European consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of Kawasaki disease–the SHARE initiative. Rheumatology 2019, 58, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo-Sánchez, V.; Anda-Gómez, M.; García-Campos, J.; Lazcano-Bautista, S.; Mendiola-Ramírez, K.; Valenzuela-Flores, A. Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de la Enfermedad de Kawasaki en el Primero, Segundo y Tercer Nivel de Atención PL México, DF; IMSS: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, E.; Song, E.J. Considerations and suggestions for the reliable analysis of miRNA in plasma using qRT-PCR. Genes 2022, 13, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Ming, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, D.; Zheng, L. Advances in nucleic acid assays for infectious disease: The role of microfluidic technology. Molecules 2024, 29, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolen, C.R.; Uduman, M.; Kleinstein, S.H. Cell subset prediction for blood genomic studies. BMC Bioinform. 2011, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhuang, W.; Li, Y.; Deng, C.; Xuan, J.; Sun, Y.; He, Y. Bioinformatic analysis and experimental verification reveal expansion of monocyte subsets with an interferon signature in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2025, 27, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Biochemical Variable | Reference Values | Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Admission | Day 3 (HS) | Day 8 (HD) | ||

| Erythrocytes (×106 g/dL) | 3.9–4.6 | 4.18 | 4.30 | 4.19 |

| Hemoglobin (gr/dL) | 11.5–12.5 | 10.9 * | 11.2 * | 11 * |

| Hematocrit (%) | 34–37 | 32.70 * | 33.4 * | 32.2 * |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) | 75–81 | 78.3 | 77.6 | 76.9 |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (pg) | 25–31 | 26.1 | 26 | 26.3 |

| RDW-CV | 12–14 | 14.3 * | 14.2 * | 14.7 * |

| Platelets (×103/µL) | 150–350 | 278 | 332 | 495 * |

| Leukocytes (K/µL) | 6–17 | 11.8 | 16.9 | 4.5 |

| Neutrophils (×103/µL) | 1.5–8.5 | 9.2 * | 11.1 * | 2.8 |

| Lymphocytes (×103/mm3) | 3–9.5 | 1.7 * | 4.9 | 1.6 * |

| Monocytes (×103/mm3) | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Eosinophils (×103/mm3) | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Basophiles (×103/µL) | 0.001–0.005 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0–0.5 | 11.10 * | 9.59 * | 5.39 * |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 4–20 | 45 * | 24 * | NT |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 12.1–14.5 | 13.1 | NT | NT |

| Partial thromboplastin time (s) | 33.6–43.8 | 66.2 * | NT | NT |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 162–401 | 468 * | 553 * | 376 |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) | 90–530 | 484 | 2988 * | 1507 * |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 60–100 | 101 * | NT | NT |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 15–38 | 30.6 | NT | NT |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 5–18 | 14.3 | NT | NT |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.3–0.7 | 0.35 | NT | NT |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0 < 0.2 | 0.139 | 0.122 | 0.10 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0–1 | 0.21 * | 0.18 | 0.04 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.3–1.2 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.14 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.6–5.2 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 3.8 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.6–7.5 | 6.9 | 6.5 | 8.2 |

| Globulins (g/dL) | 2–3 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 4.4 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 100–320 | 343.5 * | 212.9 | 194.4 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 5–30 | 35 * | 8.7 | 9.4 |

| Lactic dehydrogenase (U/L) | 110–295 | 290 | 294 | 238 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 13–35 | 35 | 23 | 29 |

| Creatine kinase (U/L) | 20–180 | 82.5 | NT | 29.2 |

| Creatine kinase MB fraction (U/L) | 23–95 | 22.79 | NT | 27.58 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 135–147 | 137 | NT | NT |

| Chlorine (mEq/L) | 97–107 | 106.36 | NT | NT |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.4–4.7 | 4.37 | NT | NT |

| Magnesium (mg/dL) | 1.6–2.4 | 2.02 | NT | NT |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4–6.5 | 3.6 | NT | NT |

| Serum calcium (mg/dL) | 8.8–10.8 | 9.29 | NT | NT |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 7–140 | 74.98 | NT | 149.06 * |

| c-ANCA (U/L) | Negative: <20 Positive: >20 | 12.5 | NT | NT |

| p-ANCA (U/L) | Negative: <20 Positive: >20 | <3.20 | NT | NT |

| E-Selectin (ng/mL) | 18.5–35 | 33.5 | NT | NT |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/mL) | 0.0–7.0 | 2.19 | NT | NT |

| Interleukin 5 (pg/mL) | 2.0–10.0 | 8.24 | NT | NT |

| Immunoglobulin E (U/mL) | 0.31–29.5 | 39.4 * | NT | NT |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 0.5–1.40 | 0.88 | NT | NT |

| Myoglobin (ng/mL) | 11.8–30.43 | 14.1 | NT | 17.2 |

| Troponin I (ng/mL) | 0.004–0.021 | 0.03 | NT | NT |

| Urine Test | Result | Reference Value |

|---|---|---|

| Physical-chemical test | ||

| Color | Yellow | Amber/Yellow |

| Appearance | Slightly cloudy | Translucent |

| pH | 6 | 5–6.5 |

| Density | 1.015 | 1.002–1.030 |

| Erythrocytes | Negative | Negative |

| Leukocytes | Negative | Negative |

| Nitrites | Negative | Negative |

| Proteins | Negative | Negative |

| Bilirubin | Negative | Negative |

| Ketones | 20 mg/dL * | <8 mg/dL |

| Glucose | Negative | Negative |

| Urobilinogen | Negative | 1 mg/dL |

| Microscopic examination | ||

| Leukocytes (per field) | 3–5 | 0–5 |

| Erythrocytes (per field) | 0–1 | 0–2 |

| Bacteria (per field) | Scarce | Negative |

| Mucoid filament | Scarce | Negative |

| Yeasts (per field) | Negative | Negative |

| Cylinders (per field) | Negative | 0–1 |

| Crystals (per field) | Negative | Negative |

| Gene | Expression Level (This Study) | Kawasaki Disease | Cutaneous Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis | Eosinophilic Vasculitis (Churg–Strauss) | Childhood-onset SLE | Viral Infection with Post-Immune Phenomenon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2 | −1.69 | ↓/↔ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| IL-4 | −1.41 | ↔ | ↔ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ |

| TNF-α | −0.22 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔/↑ |

| NF-κB | 0.21 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| IL-6 | 0.77 | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ |

| IL-12 | 1.03 | ↑ | ↑ | ↔/↑ | ↔ | ↑ |

| IL-8 | 1.64 | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| IFN-γ | 2.94 | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ |

| IL-1β | 2.96 | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| IFN-β | 6.3 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| IL-5 | 6.68 | ↔ | ↔ | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| IL-1α | 7.19 | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| IFN-α | 7.71 | ↔ | ↔ | ↔ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Pathogen | Day Result | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Human parainfluenza virus type 2 (HPIV-2) | Day 4 | Negative |

| Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV-3) | Day 4 | Negative |

| Human parainfluenza virus type 4 (HPIV-4) | Day 4 | Negative |

| Human adenovirus (HAdV) | Day 4 | Negative |

| Human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) | Day 4 | Negative |

| Human rhinovirus (HRV) | Day 4 | Positive |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez-Fierro, M.L.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Marrufo-Garcia, F.D.; Gonzalez-Plascencia, M.; Calderon-Zamora, R.C.; Sifuentes-Franco, C.; Rodriguez-Borroel, M. Immunological Profile in Atypical Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report Highlighting the Diagnostic Utility of Cytokine Analysis by qRT-PCR. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060128

Martinez-Fierro ML, Garza-Veloz I, Marrufo-Garcia FD, Gonzalez-Plascencia M, Calderon-Zamora RC, Sifuentes-Franco C, Rodriguez-Borroel M. Immunological Profile in Atypical Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report Highlighting the Diagnostic Utility of Cytokine Analysis by qRT-PCR. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(6):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060128

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez-Fierro, Margarita L., Idalia Garza-Veloz, Felipe D. Marrufo-Garcia, Manuel Gonzalez-Plascencia, Rocio C. Calderon-Zamora, Claudia Sifuentes-Franco, and Monica Rodriguez-Borroel. 2025. "Immunological Profile in Atypical Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report Highlighting the Diagnostic Utility of Cytokine Analysis by qRT-PCR" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 6: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060128

APA StyleMartinez-Fierro, M. L., Garza-Veloz, I., Marrufo-Garcia, F. D., Gonzalez-Plascencia, M., Calderon-Zamora, R. C., Sifuentes-Franco, C., & Rodriguez-Borroel, M. (2025). Immunological Profile in Atypical Kawasaki Disease: A Case Report Highlighting the Diagnostic Utility of Cytokine Analysis by qRT-PCR. Pediatric Reports, 17(6), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060128