Parental Knowledge and Acceptance of Pediatric Lumbar Puncture in Northern Saudi Arabia: Implications for Clinical Practice and Education: A Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Sample Size Determination

2.4. Data Collection Tool and Questionnaire Development

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

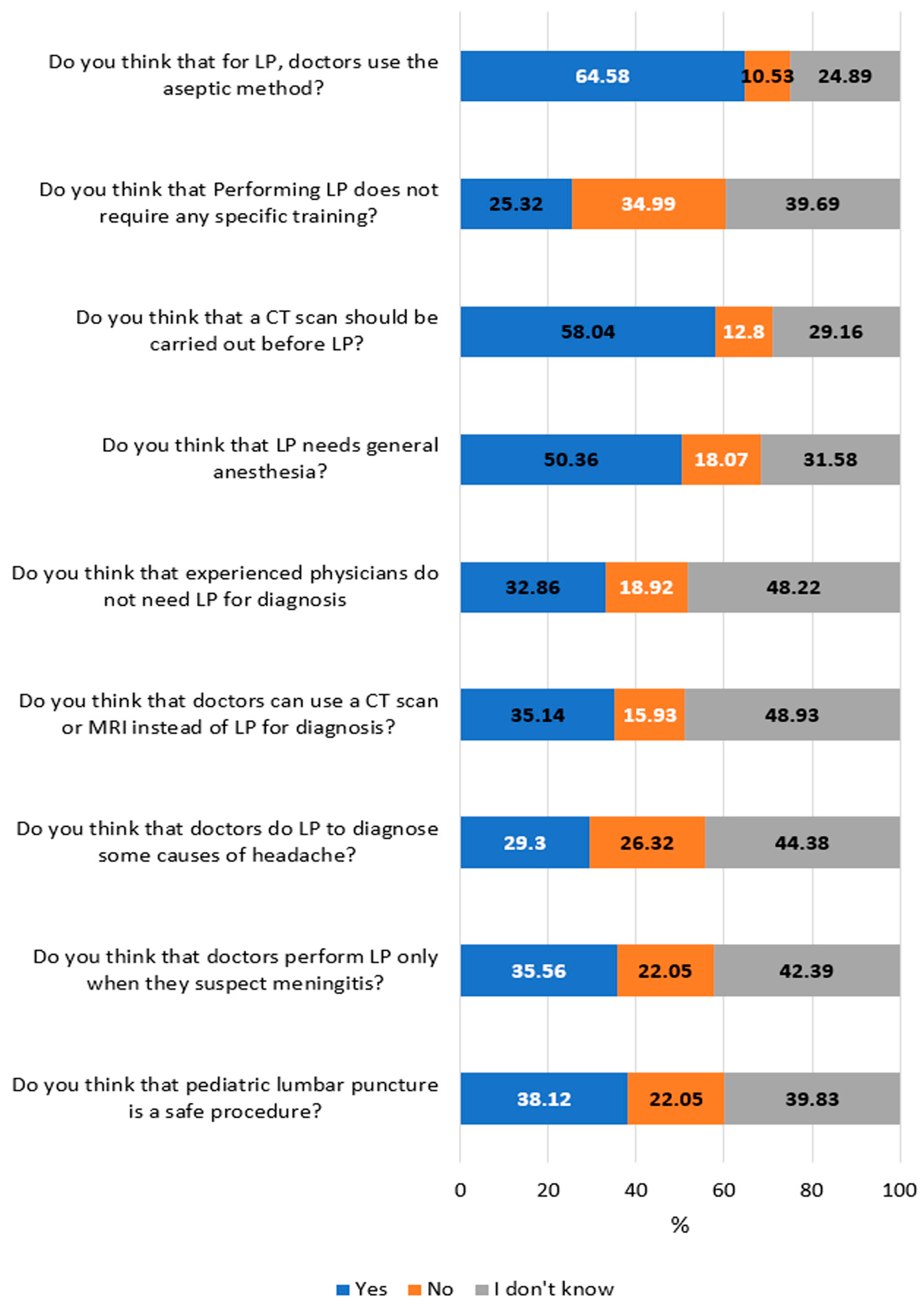

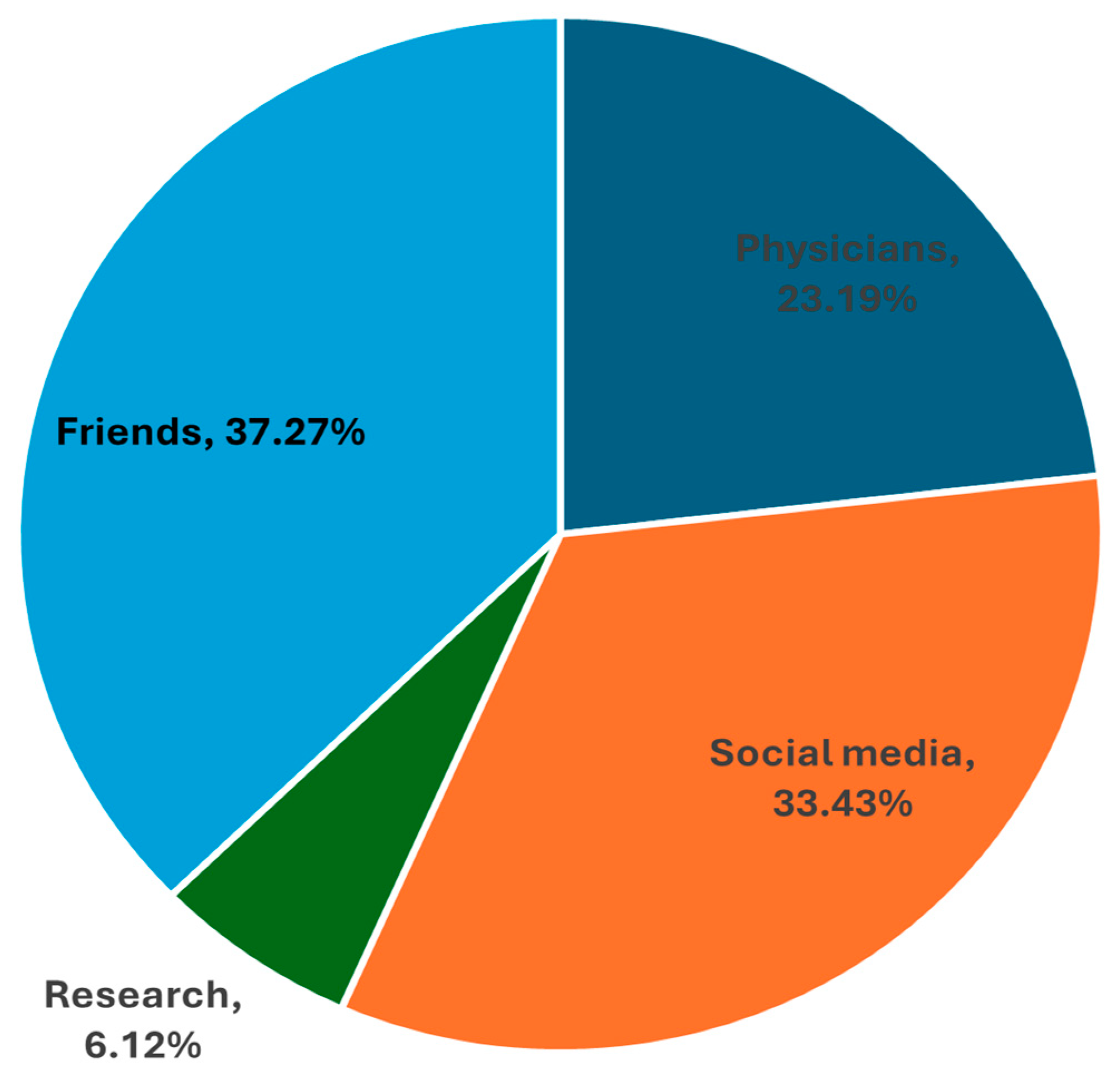

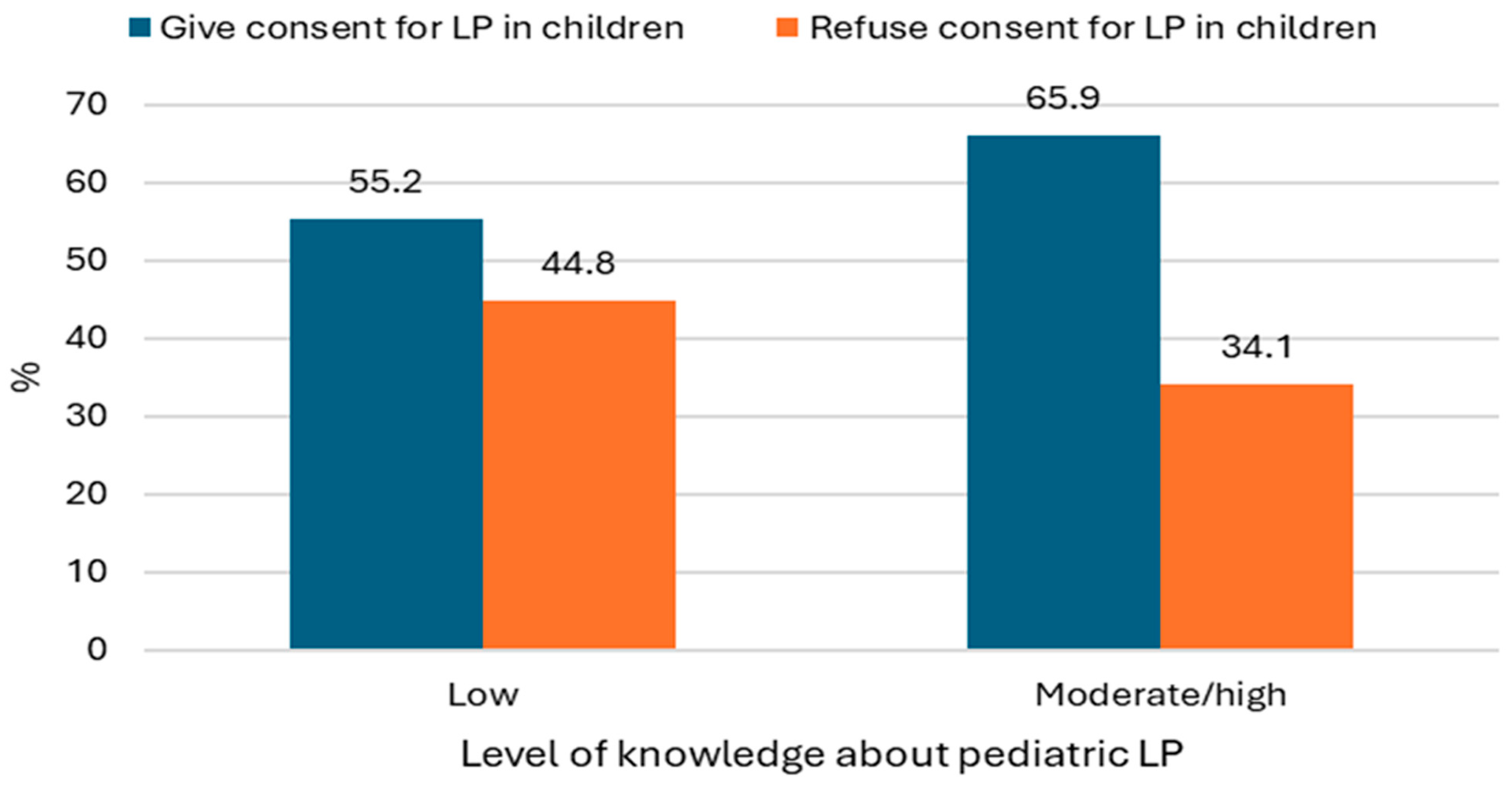

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| FET | Fisher’s exact test |

| LP | Lumbar puncture |

| No | Number |

| OR | Odds ratio |

References

- Yücel, D.; Ülgen, Y. A novel approach to CSF pressure measurement via lumbar puncture that shortens the clinical measurement time with a high level of accuracy. BMC Neurosci. 2023, 24, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, T.G.; Menéndez-González, M.; Schreiner, O.D.; Ciobanu, R.C. Intrathecal Therapies for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Review of Current Approaches and the Urgent Need for Advanced Delivery Systems. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelborghs, S.; Niemantsverdriet, E.; Struyfs, H.; Blennow, K.; Brouns, R.; Comabella, M.; Dujmovic, I.; van der Flier, W.; Frölich, L.; Galimberti, D.; et al. Consensus guidelines for lumbar puncture in patients with neurological diseases. Alzheimer’s Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2017, 8, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaibari, K.S.; Hasan, E.R.; Dammaj, M.Z.; Sharaf Adeen, I.A. Mothers’ Views About Lumbar Puncture for Their Children in a Maternity and Children’s Hospital in Najran, Saudi Arabia. Pediatr. Health Med. Ther. 2021, 12, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisbush, T.R.; Matys, T.; Massoud, T.F.; Hacein-Bey, L. Dural Puncture Complications. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 2025, 35, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Cong, L.; Ma, W. A controlled lumbar puncture procedure improves the safety of lumbar puncture. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1304150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingebrigtsen, S.G.; Eltoft, A.; Kilvaer, T.K. Zeroing in: Achieving zero complications in lumbar puncture—A quality improvement initiative to reduce complications at the University Hospital of North Norway. BMJ Open Qual. 2025, 14, e003327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, K.T.; Mateyo, K.; Hachaambwa, L.; Kayamba, V.; Mallewa, M.; Mallewa, J.; Nwazor, E.O.; Lawal, T.; Mallum, C.B.; Atadzhanov, M. Lumbar puncture refusal in sub-Saharan Africa: A call for further understanding and intervention. Neurology 2015, 84, 1988–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwahbi, Z.M.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Alqhtani, M.M.; Asiri, W.I.; Assiri, M.A. Evaluation of Saudi Arabian parent’s attitude towards lumbar puncture in their children for diagnosis of meningitis. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2018, 70, 1582–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, W.A.W.; Saliluddin, S.M.; Ong, Y.J.; Lim, S.M.S.; Mat, L.N.I.; Hoo, F.K.; Vasudevan, R.; Ching, S.M.; Basri, H.; Mohamed, M.H. A cross sectional study assessing the knowledge and attitudes towards lumbar puncture among the staff of a public university in Malaysia. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2018, 6, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acoglu, E.A.; Oguz, M.M.; Sari, E.; Yucel, H.; Akcaboy, M.; Zorlu, P.; Sahin, S.; Senel, S. Parental Attitudes and Knowledge About Lumbar Puncture in Children. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2021, 37, e380–e383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.; Kara-Aksay, A.; Demir, G.; Ekemen-Keles, Y.; Ustundag, G.; Berksoy, E.; Karadag-Oncel, E.; Yilmaz, D. Parental Attitudes About Lumbar Puncture in Children with Suspected Central Nervous System Infection. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2023, 39, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, N.N.; Sadoon, S.T.; Jaafar, M.M.; Nori, W. Factors affecting parental refusal of lumbar puncture in Iraqi children in COVID-19 era: A cross-sectional study. JPMA J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2024, 74, S219–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, E.S.; Alwabel, A.S.; Algaith, N.K.; Alqarzaee, R.S.; Alharbi, R.H.; Alkuraydis, S.F.; Alrashidi, I.A. Procedure and Treatment Refusal in Pediatric Practice: A Single-Center Experience at a Children’s Hospital in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2025, 17, e80936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, E.; Husain, E.H.; Fathy, H.; Shawky, A. Perceptions and attitudes towards lumbar puncture (LP) among parents in Kuwait. Kuwait Med. J. 2009, 41, 306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Narchi, H.; Ghatasheh, G.; Hassani, N.A.; Reyami, L.A.; Khan, Q. Comparison of underlying factors behind parental refusal or consent for lumbar puncture. World J. Pediatr. WJP 2013, 9, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almatawah, Y.; Busaleh, F.; Alkhars, A.; Almarzooq, W.; Almarzooq, M.; Alkhars, A.; Almarzooq, A.; Albaqshi, A.; Alkhars, F. Knowledge and attitude of parents toward pediatric lumbar puncture and its relationship with demographical factors in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia. Med. Sci. 2020, 24, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar]

- Aldayel, A.Y.; Alharbi, M.M.; Almasri, M.S.; Alkhonezan, S.M. Public knowledge and attitude toward lumbar puncture among adults in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7, 2050312119871066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemri, A.A.; Asiri, S.S.; Mansouri, F.F. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Among Caregivers About Lumbar Puncture in the Pediatric Age Group in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2025, 17, e87925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamaga, A.K.; Alyazidi, A.S.; Almubarak, A.; Almohammal, M.N.; Alharthi, A.S.; Alsehemi, M.A. Pediatric Neurology Workforce in Saudi Arabia: A 5-Year Update. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızıilay, D.Ö.; Kırdök, A.A.; Ertan, P.; Ayça, S.; Polat, M.; Demet, M.M. Bilgi Güçtür: Febril Konvülsiyon Geçiren Çocukların Aileleri Üzerine Müdahaleli Bir Çalışma. J. Pediatr. Res. 2017, 4, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, S.; Farrukh, R.; Naseer, A.; Saqib, M.; Kadri, A.; Shakoor, I.; Mustafa, S.; Mumtaz, H. Factors influencing refusal of lumbar puncture in children under age 10: A cross-sectional study. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 5372–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhebshi, A.; Alrebaiee, S.; Farahat, J. Etiologies of Lumbar Puncture Refusal in Pediatric Patients in Children’s Hospital, Taif City, Saudi Arabia. A Cross-Sectional Study. World Fam. Med. J. Inc. Middle East J. Fam. Med. 2021, 19, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muammar, N.; Rohaimi, N.; Aleid, B.; Harbi, A.; Yousif, A. Level of awareness of parents towards pediatric lumbar punctures in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 1, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.; Donnelly, J.P.; Moore, J.X.; Barnum, S.R.; Schein, T.N.; Wang, H.E. Epidemiology of lumbar punctures in hospitalized patients in the United States. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elafros, M.A.; Belessiotis-Richards, C.; Birbeck, G.L.; Bond, V.; Sikazwe, I.; Kvalsund, M.P. Lumbar Puncture-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices among Patients, Caregivers, Doctors, and Nurses in Zambia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 104, 1925–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashcraft, L.E.; Asato, M.; Houtrow, A.J.; Kavalieratos, D.; Miller, E.; Ray, K.N. Parent Empowerment in Pediatric Healthcare Settings: A Systematic Review of Observational Studies. Patient 2019, 12, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.; Ejaz, M.; Nasir, S.; Mainosh, S.; Jahangeer, A.; Bhatty, M.; Razi, Z. Parental Refusal to Lumbar Puncture: Effects on Treatment, Hospital Stay and Leave Against Medical Advice. Cureus 2020, 12, e7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez Vera, A.; Thomas, K.; Trinh, C.; Nausheen, F. A Case Study of the Impact of Language Concordance on Patient Care, Satisfaction, and Comfort with Sharing Sensitive Information During Medical Care. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2023, 25, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsah, M.H.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Alsohime, F.; Alhasan, K.A.; Bashiri, F.A.; Salleeh, H.B.; Hasan, G.M.; Alhaboob, A.; Al-Sabei, N.; Al-Wehaibi, A.; et al. Effect of lumbar puncture educational video on parental knowledge and self-reported intended practice. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2021, 8, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | No. | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 18–25 | 229 | 32.57 |

| 26–35 | 228 | 32.43 | |

| 36–46 | 163 | 23.19 | |

| >46 | 83 | 11.81 | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 672 | 95.59 |

| Non-Saudi | 31 | 4.41 | |

| Parents | Father | 277 | 39.40 |

| Mother | 426 | 60.60 | |

| Number of children | One child | 254 | 36.13 |

| Two children | 102 | 14.51 | |

| >2 children | 347 | 49.36 | |

| Parents’ educational status | University or higher | 580 | 82.50 |

| Secondary school | 93 | 13.23 | |

| Preparatory school | 12 | 1.71 | |

| Primary school | 11 | 1.56 | |

| No educational certificate | 7 | 1.00 | |

| Parents’ occupation | Governmental employee | 561 | 79.80 |

| Private employee | 78 | 11.10 | |

| Unemployed | 64 | 9.10 | |

| Household income | Low | 94 | 13.37 |

| Medium | 425 | 60.46 | |

| High | 184 | 26.17 | |

| Characteristic | Low Knowledge (n = 442) | Moderate/High Knowledge (n = 261) | OR (95%CI) | χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||||

| Age (year) | 18–25 | 119 | 26.92 | 110 | 42.15 | 1.98 (1.41–2.77) *** | 18.00 | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 151 | 34.16 | 77 | 29.50 | 0.81 (0.57–1.14) | |||

| 36–46 | 114 | 25.79 | 49 | 18.77 | 0.66 (0.45–0.98) * | |||

| >46 | 58 | 13.12 | 25 | 9.58 | 0.70 (0.41–1.18) | |||

| Nationality | Saudi | 425 | 96.15 | 247 | 94.64 | 0.70 (0.32–1.57) | 0.90 | 0.34 |

| Non-Saudi | 17 | 3.85 | 14 | 5.36 | ||||

| Parents | Father | 148 | 33.48 | 129 | 49.43 | 0.51 (0.37–0.71) *** | 17.46 | <0.001 |

| Mother | 294 | 66.52 | 132 | 50.57 | ||||

| Number of children | One child | 108 | 24.43 | 146 | 55.94 | 3.93 (2.79–5.52) *** | 71.39 | <0.001 |

| Two children | 72 | 16.29 | 30 | 11.49 | 0.67 (0.41–1.07) | |||

| >2 children | 262 | 59.28 | 85 | 32.57 | 0.33 (0.24–0.46) *** | |||

| Parents’ educational status | University or higher | 373 | 84.39 | 207 | 79.31 | 0.71 (0.47–1.07) | FET | 0.04 |

| Secondary school | 49 | 11.09 | 44 | 16.86 | 1.63 (1.02–2.58) * | |||

| Preparatory school | 7 | 1.58 | 5 | 1.92 | 1.21 (0.30–4.49) | |||

| Primary school | 6 | 1.36 | 5 | 1.92 | 1.42 (0.34–5.64) | |||

| No educational certificate | 7 | 1.58 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 (0–0.92) * | |||

| Parents’ occupation | Governmental employee | 363 | 82.13 | 198 | 75.86 | 0.68 (0.46–1.01) * | 4.01 | 0.13 |

| Private employee | 43 | 9.73 | 35 | 13.41 | 1.44 (0.86–2.37) | |||

| Unemployed | 36 | 8.14 | 28 | 10.73 | 1.35 (0.77–2.35) | |||

| Household income | Low | 44 | 9.95 | 50 | 19.16 | 2.14 (1.35–3.40) *** | 16.60 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 266 | 60.18 | 159 | 60.92 | 1.03 (0.74–1.43) | |||

| High | 132 | 29.86 | 52 | 19.92 | 0.58 (0.40–0.85) ** | |||

| Accept LP in Children (n = 416; 59.17%) | Refusing LP in Children (n = 287; 40.83%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasons * | No. | % | Reasons * | No. | % |

| Taking the advice of the doctor | 362 | 87.02 | Fear of paralysis | 231 | 80.49 |

| Possibly diagnostic | 141 | 33.89 | Injection site danger | 236 | 82.23 |

| Potentially therapeutic | 176 | 42.31 | Fear of death | 224 | 78.05 |

| Characteristics | Accept (n = 416; 59.17%) | Refusing (n = 287; 40.83%) | OR (95%CI) | χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | |||||

| Age (year) | 18–25 | 140 | 33.65 | 89 | 31.01 | 1.13 (0.81–1.58) | 28.5 | <0.001 |

| 26–35 | 160 | 38.46 | 68 | 23.69 | 2.01 (1.42–2.86) *** | |||

| 36–46 | 82 | 19.71 | 81 | 28.22 | 0.62 (0.43–0.90) ** | |||

| >46 | 34 | 8.17 | 49 | 17.07 | 0.43 (0.26–0.71) *** | |||

| Nationality | Saudi | 398 | 95.67 | 274 | 95.47 | 1.05 (0.46–2.30) | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| Non-Saudi | 18 | 4.33 | 13 | 4.53 | ||||

| Parents | Father | 159 | 38.22 | 118 | 41.11 | 0.89 (0.64–1.22) | 0.59 | 0.44 |

| Mother | 257 | 61.78 | 169 | 58.89 | ||||

| Number of children | One child | 157 | 37.74 | 97 | 33.80 | 1.19 (0.86–1.65) | 2.37 | 0.30 |

| Two children | 54 | 12.98 | 48 | 16.72 | 0.74 (0.48–1.16) | |||

| >2 children | 205 | 49.28 | 142 | 49.48 | 0.99 (0.73–1.35) | |||

| Parents’ educational status | University or higher | 349 | 83.89 | 231 | 80.49 | 1.26 (0.83–1.90) | FET | 0.75 |

| Secondary school | 51 | 12.26 | 42 | 14.63 | 0.81 (0.51–1.30) | |||

| Preparatory school | 7 | 1.68 | 5 | 1.74 | 0.96 (0.26–3.90) | |||

| Primary school | 6 | 1.44 | 5 | 1.74 | 0.82 (0.21–3.45) | |||

| No educational certificate | 3 | 0.72 | 4 | 1.39 | 0.51 (0.07–3.06) | |||

| Parents’ occupation | Governmental employee | 344 | 82.69 | 217 | 75.61 | 1.54 (1.04–2.27) * | 5.99 | 0.05 |

| Private employee | 42 | 10.10 | 36 | 12.54 | 0.78 (0.47–1.29) | |||

| Unemployed | 30 | 7.21 | 34 | 11.85 | 0.58 (0.33–1.00) * | |||

| Household income | Low | 64 | 15.38 | 30 | 10.45 | 1.56 (0.96–2.56) | 30.02 | <0.001 |

| Medium | 217 | 52.16 | 208 | 72.47 | 0.41 (0.29–0.58) *** | |||

| High | 135 | 32.45 | 49 | 17.07 | 2.33 (1.59–3.45) *** | |||

| Characteristic | Level of Knowledge | Attitudes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Logistic Regression | Multiple Logistic Regression | Univariate Logistic Regression | Multiple Logistic Regression | |||||

| OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | OR (95%CI) | p | |

| Age (year) | ||||||||

| 18–25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 26–35 | 0.55 (0.38–0.90) | 0.002 | 0.69 (0.46–1.02) | 0.06 | 1.49 (1.01–2.21) | 0.04 | 1.54 (1.02–2.32) | 0.04 |

| 36–46 | 0.46 (0.30–0.71) | <0.001 | 0.53 (0.34–0.83) | 0.006 | 0.64 (0.43–0.96) | 0.03 | 0.86 (0.56–1.33) | 0.51 |

| >46 | 0.47 (0.27–0.80) | 0.005 | 0.47(0.27–0.81) | 0.006 | 0.44 (0.26–0.73) | 0.002 | 0.51 (0.30–0.86) | 0.01 |

| Nationality | ||||||||

| Saudi vs. non-Saudi | 0.70 (0.34–1.46) | 0.35 | 1.05 (0.50–2.18) | 0.90 | ||||

| Parents | ||||||||

| Mother vs. father | 0.51 (0.38–0.70) | <0.001 | 0.62 (0.44–0.87) | 0.006 | 1.13 (0.83–1.53) | 0.44 | ||

| Number of children | ||||||||

| One child | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Two children | 0.31 (0.19–0.50) | <0.001 | 0.31 (0.19–0.51) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.44–1.10) | 0.12 | ||

| >2 children | 0.24 (0.17–0.34) | <0.001 | 0.26 (0.18–0.37) | <0.001 | 0.89 (0.64–1.24) | 0.50 | ||

| Parents’ educational status | ||||||||

| University or higher | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Secondary school | 1.62 (1.04–2.51) | 0.03 | 0.80 (0.52–1.25) | 0.33 | ||||

| Preparatory school | 1.29 (0.40–4.11) | 0.67 | 0.93 (0.29–2.95) | 0.90 | ||||

| Primary school | 1.50 (0.45–4.98) | 0.51 | 0.79 (0.24–2.63) | 0.71 | ||||

| No educational certificate | Empty | 0.50 (0.11–2.24) | 0.36 | |||||

| Parents’ occupation | ||||||||

| Governmental employee | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Private employee | 0.70 (0.41–1.18) | 0.18 | 1.80 (1.07–3.02) | 0.03 | ||||

| Unemployed | 1.05 (0.54–2.04) | 0.89 | 1.32 (0.68–2.56) | 0.41 | ||||

| Household income | ||||||||

| Low | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Medium | 0.53 (0.33–0.82) | 0.005 | 0.72 (0.45–1.17) | 0.19 | 0.49 (0.30–0.78) | 0.003 | 0.51 (0.31–0.84) | 0.008 |

| High | 0.35 (0.21–0.58) | <0.001 | 0.48 (0.28–0.84) | 0.01 | 1.29 (0.75–2.22) | 0.36 | 1.23 (0.70–2.18) | 0.47 |

| Level of knowledge | ||||||||

| Moderate/high vs. low | 1.57 (1.14–2.15) | 0.005 | 1.60 (1.15–2.23) | 0.006 | ||||

| Author/Year * [Reference] | Study Location | Sample Size | Reported Outcome(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aldayel et al./2019 [18] | Riyadh | 1223 questionnaires | Public ignorance about the LP technique foretells an unacceptably negative attitude toward the method. |

| Almatawah et al./2020 [17] | Al-Ahsa | 466 participants | 90% of participants had poor knowledge of LP, which was associated with a negative attitude towards LP. |

| Alshaibari, et al./2021 [4] | Najran | 202 mothers | Of the respondents, four out of ten (40.6%) had never heard of LP. A significant minority of 89 mothers (44.0%) declined to give their kids LP. |

| Muammar NB et al./2022 [24] | Riyadh | 1276 parents | 56.1% had a bad perception, and 51.1% had poor knowledge of LP |

| Nemri et al./2025 [19] | Western Region of Saudi Arabia | 993 participants | low knowledge in 75.5% of the participants. |

| Solution/Intervention | Key Actors | Implementation Approach | Practical Notes/Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician-Led Parental Education | Physicians, Residents | Use clear pre-procedural counseling, standardized consent/education forms | Requires physician training in risk communication |

| Community Health Campaigns | Health authorities, NGOs | Social media, clinics, schools, culturally adapted leaflets, videos, Q&A events | Must address local language and misconceptions |

| Multidisciplinary Team Involvement | Nurses, Allied health staff | Nurses reinforce counseling, answer questions, and provide emotional support. | Coordination and engagement of non-physician staff are needed |

| Partnering with Local Community Leaders | Faith/community leaders | Include messages in religious gatherings, community events, and trusted influencers. | May facilitate trust and address cultural/religious gaps |

| Monitoring and Evaluation | Policymakers, Researchers | Assess impact, gather feedback, adapt approaches | Needs ongoing funding and stakeholder buy-in |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alenezi, D.F.K.; Alanazi, R.M.T.; Almatrafi, F.F.S.; Alanazi, R.M.O.; Alenezy, N.S.K.; Alanazi, D.A.J.; Alanazi, S.W.A.; Alanazi, R.S.Z.; Alenezi, A.H.; Abu Alsel, B.; et al. Parental Knowledge and Acceptance of Pediatric Lumbar Puncture in Northern Saudi Arabia: Implications for Clinical Practice and Education: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060129

Alenezi DFK, Alanazi RMT, Almatrafi FFS, Alanazi RMO, Alenezy NSK, Alanazi DAJ, Alanazi SWA, Alanazi RSZ, Alenezi AH, Abu Alsel B, et al. Parental Knowledge and Acceptance of Pediatric Lumbar Puncture in Northern Saudi Arabia: Implications for Clinical Practice and Education: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(6):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060129

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlenezi, Dana Faez K., Rahaf Maqil T. Alanazi, Fai Fihat S. Almatrafi, Reema Mubarak O. Alanazi, Nouf Swilim K. Alenezy, Dalia Aqeel J. Alanazi, Shahad Wadi A. Alanazi, Rahaf Salman Z. Alanazi, Ayman Hamed Alenezi, Baraah Abu Alsel, and et al. 2025. "Parental Knowledge and Acceptance of Pediatric Lumbar Puncture in Northern Saudi Arabia: Implications for Clinical Practice and Education: A Cross-Sectional Study" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 6: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060129

APA StyleAlenezi, D. F. K., Alanazi, R. M. T., Almatrafi, F. F. S., Alanazi, R. M. O., Alenezy, N. S. K., Alanazi, D. A. J., Alanazi, S. W. A., Alanazi, R. S. Z., Alenezi, A. H., Abu Alsel, B., Bayomy, H. E., Esmaeel, S. E., & Fawzy, M. S. (2025). Parental Knowledge and Acceptance of Pediatric Lumbar Puncture in Northern Saudi Arabia: Implications for Clinical Practice and Education: A Cross-Sectional Study. Pediatric Reports, 17(6), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060129