Two Rare Cases of Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis in Neonates

Abstract

1. Introduction

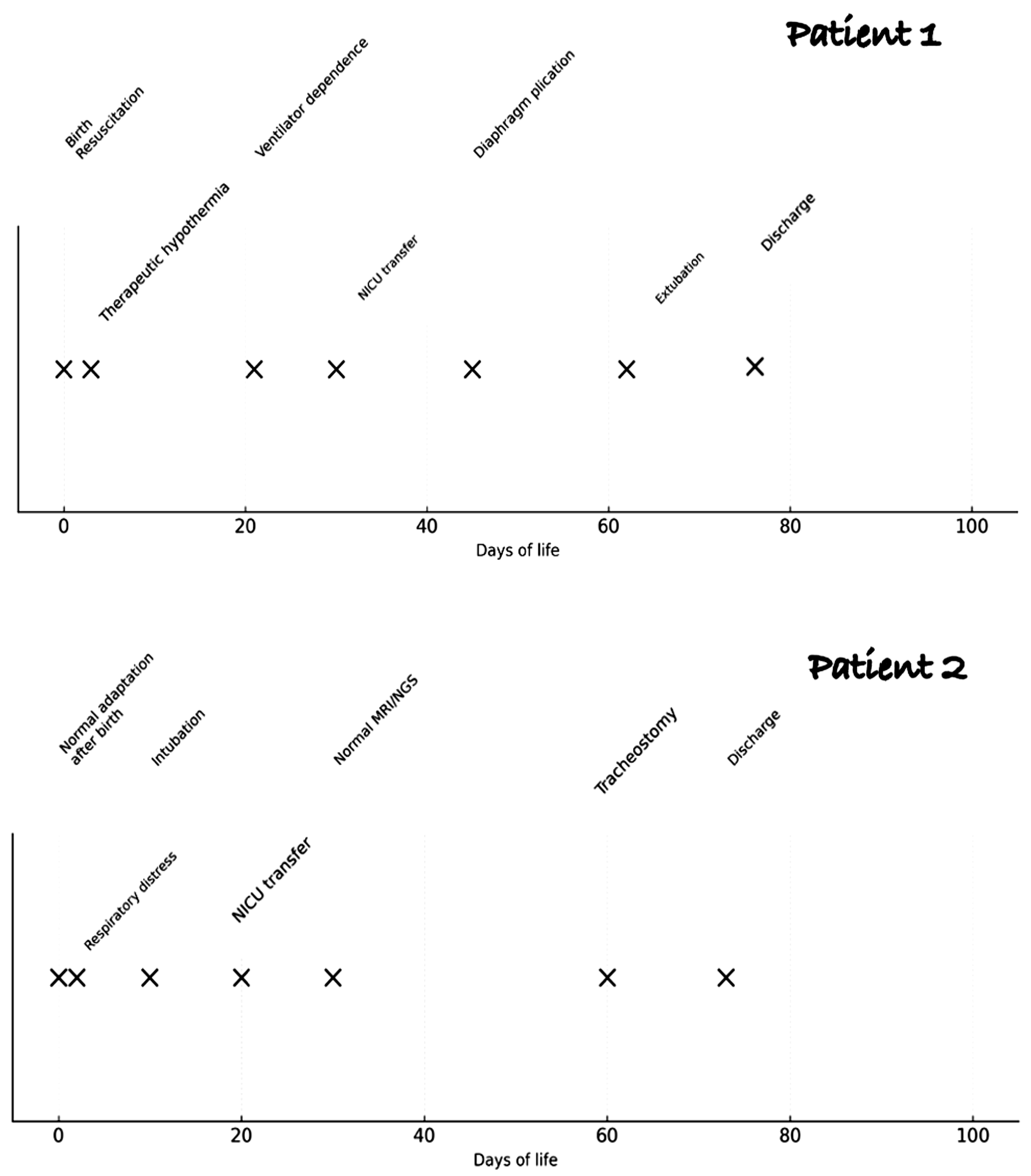

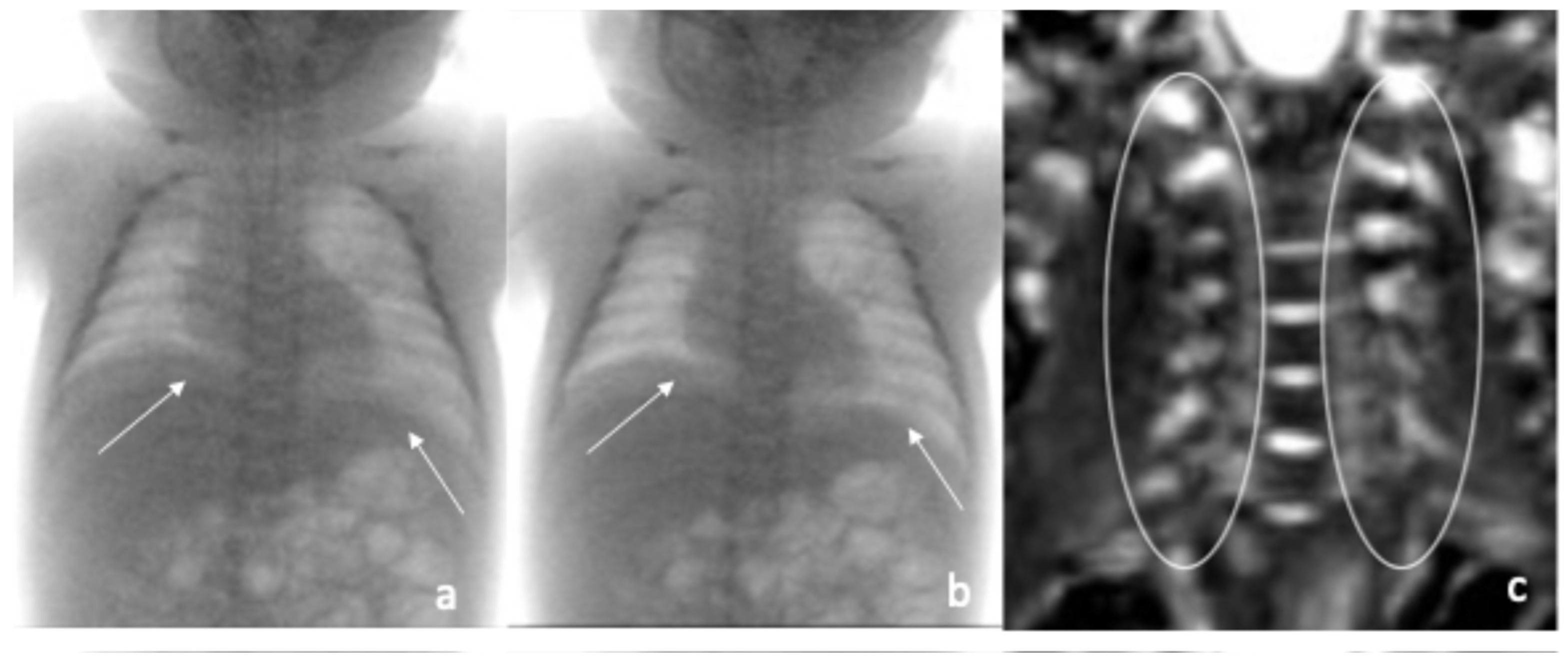

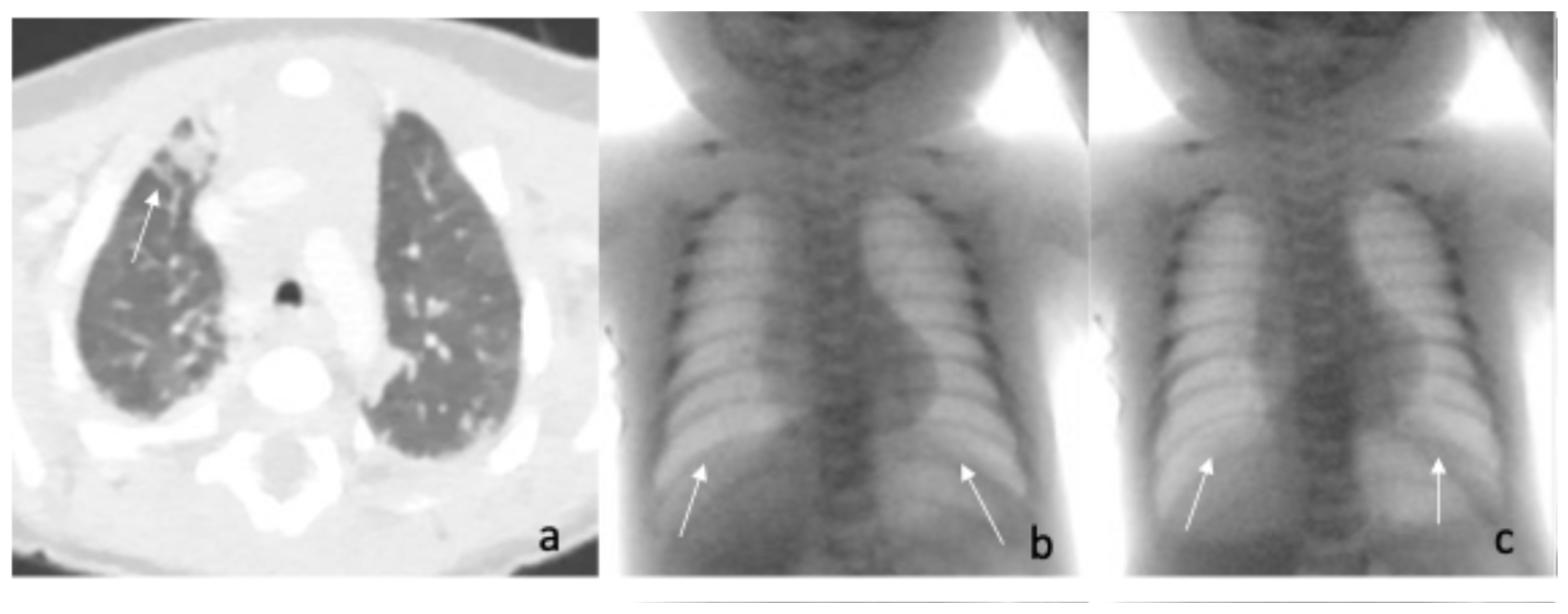

2. Case Reports

3. Discussion

3.1. Diagnostic Approach

3.2. Therapeutic Approach

3.3. Our Clinical Challenges

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DP | Diaphragmatic paralysis |

| PN | Phrenic nerve |

| BP | Brachial plexus |

| BPP | Brachial plexus paralysis |

| CMAP | Compound muscle action potential |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| UPD | Uniparental disomy |

| NICU | Neonatal intensive care unit |

| EEG | Electroencephalogram |

| LGA | Large for gestational age |

| HFNC | High Flow Nasal Cannula |

| nCPAP | Nasal Continuous Positive Airway Pressure |

| LUS | Lung ultrasound |

| NGS | Next generation Sequency |

| SNP-array | Single nucleotide polymorphism-array |

| SMARD1 | Spinal Muscular Atrophy with Respiratory Distress type 1 |

| MD1 | Myotonic Dystrophy type 1 |

| EMARD | Early-onset myopathy, areflexia, dysphagia, and respiratory distress |

References

- Zifko, U.; Hartmann, M.; Girsch, W.; Zoder, G.; Rokitansky, A.; Grisold, W.; Lischka, A. Diaphragmatic paresis in newborns due to phrenic nerve injury. Neuropediatrics 1995, 26, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, T.K.; Herman, J.H.; Rochester, D.F. Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis in the newborn infant. J. Pediatr. 1980, 97, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commare, M.C.; Kurstjens, S.P.; Barois, A. Diaphragmatic paralysis in children: A review of 11 cases. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 1994, 18, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, T.S.; Koens, B.L.; Vos, A. Surgical treatment of diaphragmatic eventration caused by phrenic nerve injury in the newborn. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1998, 33, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akay, T.H.; Ozkan, S.; Gultekin, B.; Uguz, E.; Varan, B.; Sezgin, A.; Tokel, K.; Aslamaci, S. Diaphragmatic paralysis after cardiac surgery in children: Incidence, prognosis and surgical management. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2006, 22, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Kawabata, H. The prognostic value of concurrent phrenic nerve palsy in newborn babies with neonatal brachial plexus palsy. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2015, 40, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowerson, M.; Nelson, V.S.; Yang, L.J.S. Diaphragmatic Paralysis Associated with Neonatal Brachial Plexus Palsy. Pediatr. Neurol. 2010, 42, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.A. Part 2: Birth trauma: Injuries to the intraabdominal organs, peripheral nerves, and skeletal system. Adv. Neonatal Care Off. J. Natl. Assoc. Neonatal Nurses 2006, 6, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard-Castaing, N.; Perrin, T.; Ohlmann, C.; Mainguy, C.; Coutier, L.; Buchs, C.; Reix, P. Diaphragmatic paralysis in young children: A literature review. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2019, 54, 1367–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BOWMAN, E.D.; MURTON, L.J. A case of neonatal bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis requiring surgery. J. Paediatr. Child. Health 1984, 20, 331–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, R.; Nishioka, T.; Fukumasu, H.; Yokota, Y. Bilateral phrenic nerve palsy in the newborn infant. A case report. J. Pediatr. 1976, 89, 986–987. [Google Scholar]

- Stramrood, C.A.I.; Blok, C.A.; van der Zee, D.C.; Gerards, L.J. Neonatal phrenic nerve injury due to traumatic delivery. J. Perinat. Med. 2009, 37, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, Y.; Galvis, A. Early diaphragmatic paralysis. In infants with genetic disorders. Clin. Pediatr. 1990, 29, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, E.; Gadisseux, J.L.; Palmieri, G.; Ricci, E.; Di Capua, M.; Ferriere, G.; Lyon, G. Distal infantile spinal muscular atrophy associated with paralysis of the diaphragm: A variant of infantile spinal muscular atrophy. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1989, 33, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heckmatt, J.Z.; Placzek, M.; Thompson, A.H.; Dubowitz, V.; Watson, G. An unusual case of neonatal myasthenia. J. Child. Neurol. 1987, 2, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, C.E.; Matalon, S.V.; Thompson, T.R.; Demuth, S.; Loew, J.M.; Liu, H.M.; Mastri, A.; Burke, B.; De Reuck, J.; Hooft, C.; et al. A progressive congenital myopathy. Initial involvement of the diaphragm with type I muscle fiber atrophy. Clin. Pediatr. 1978, 29, 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bosman, C.; Bachelet, V.; Boldrini, R.; Bertini, E. Diaphragmatic paralysis due to partial diaphragmatic hypoplasia mimicking a localized muscular dystrophy: A case report. Clin. Neuropathol. 1988, 7, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lv, Y.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, J.; Gao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Gai, Z. Phenotype and genotype analyses of Chinese patients with autosomal dominant mental retardation type 5 caused by SYNGAP1 gene mutations. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 957915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.B. Diaphragmatic paralysis in the newborn. Am. J. Dis. Child. 1945, 70, 253. [Google Scholar]

- Nason, L.K.; Walker, C.M.; McNeeley, M.F.; Burivong, W.; Fligner, C.L.; Godwin, J.D. Imaging of the diaphragm: Anatomy and function. Radiogr. A Rev. Publ. Radiol. Soc. N. Am. Inc. 2012, 32, E51–E70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez De Toledo, J.; Munoz, R.; Landsittel, D.; Shiderly, D.; Yoshida, M.; Komarlu, R.; Wearden, P.; Morell, V.O.; Chrysostomou, C. Diagnosis of abnormal diaphragm motion after cardiothoracic surgery: Ultrasound performed by a cardiac intensivist vs. fluoroscopy. Congenit. Heart Dis. 2010, 5, 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Juanmiquel, L.; Gratacós, M.; Castilla-Fernández, Y.; Piqueras, J.; Baust, T.; Raguer, N.; Balcells, J.; Perez-Hoyos, S.; Abella, R.F.; Sanchez-De-Toledo, J. Bedside Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Abnormal Diaphragmatic Motion in Children After Heart Surgery. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 18, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizeq, Y.K.; Many, B.T.; Vacek, J.C.; Reiter, A.J.; Raval, M.V.; Abdullah, F.; Goldstein, S.D.; Denamur, S.; Chenouard, A.; Lefort, B.; et al. Role of point-of-care ultrasound in the management of congenital diaphragmatic palsy. BMJ Case Rep. 2025, 18, e266951. [Google Scholar]

- Yemisci, O.U.; Cosar, S.N.S.; Karatas, M.; Aslamaci, S.; Tokel, K. A prospective study of temporal course of phrenic nerve palsy in children after cardiac surgery. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2011, 28, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, S.; Hemli, J.A.; Sujov, P.O.; Braun, J. Neonatal bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis caused by brain stem haemorrhage. Arch. Dis. Child. 1989, 64, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimbault, J.; Renault, F.; Laget, P. Technic and results of electromyographic exploration of the diaphragm in the infant and young child. Rev. Electroencephalogr. Neurophysiol. Clin. 1983, 13, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitting, J.W.; Grassino, A. Diagnosis of diaphragmatic dysfunction. Clin. Chest Med. 1987, 8, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waters, P.M. Obstetric Brachial Plexus Injuries: Evaluation and Management. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 1997, 5, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagama, Y.; Kaneko, Y.; Ono, H. Reversible diaphragmatic paralysis caused by a malpositioned chest tube. Cardiol. Young 2015, 25, 1382–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Hari, P.; Bagga, A.; Mehta, S.N. Phrenic nerve palsy: A rare complication of indwelling subclavian vein catheter. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2000, 14, 203–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Netto, M.A.; Bender, J.; Brown, R.T.; Herson, V.C. Unilateral diaphragmatic palsy in association with a subclavian vein thrombus in a very-low- birth-weight infant. Am. J. Perinatol. 2001, 18, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosello, B.; Michel, F.; Merrot, T.; Chaumoître, K.; Hassid, S.; Lagier, P.; Martin, C. Hemidiaphragmatic paralysis in preterm neonates: A rare complication of peripherally inserted central catheter extravasation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, E17–E21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mir, S.; Serdaroglu, E. An Elevated Hemidiaphragm 3 Months After Internal Jugular Vein Hemodialysis Catheter Placement. Semin. Dial. 2003, 16, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foad, S.L.; Mehlman, C.T.; Ying, J. The epidemiology of neonatal brachial plexus palsy in the United States. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2008, 90, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.; Watt, J.; Olson, J.; Van Aerde, J. Perinatal brachial plexus palsy. Paediatr. Child. Health 2006, 11, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostakis, D.; Economou-Mavrou, C.; Moschos, A.; Vlachos, P.; Liakakos, D. Diaphragmatic paralysis in the newborn. Arch. Dis. Child. 1973, 48, 977–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, A.J.; Rizeq, Y.K.; Many, B.T.; Vacek, J.C.; Abdullah, F.; Goldstein, S.D. A Rare Case of Contralateral Diaphragm Paralysis Following Birth Injury with Brachial Plexus Palsy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2020, 2020, 8844029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegu, S.; Deb, B.; Kalapesi, Z. Rare case of a newborn baby with left-sided Erb’s palsy and a contralateral/right-sided paralysis of the diaphragm. BMJ Case Rep. 2018, 2018, bcr-2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladini, M.; Nizzardo, M.; Govoni, A.; Taiana, M.; Bresolin, N.; Comi, G.P.; Corti, S. Spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress type 1: Clinical phenotypes, molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic insights. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Gutiérrez, G.; Díaz-Manera, J.; Almendrote, M.; Azriel, S.; Eulalio Bárcena, J.; Cabezudo García, P.; Camacho Salas, A.; Casanova Rodríguez, C.; Cobo, A.M.; Díaz Guardiola, P.; et al. Clinical guide for the diagnosis and follow-up of myotonic dystrophy type 1, MD1 or Steinert’s disease. Neurología 2020, 35, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croci, C.; Traverso, M.; Baratto, S.; Iacomino, M.; Pedemonte, M.; Caroli, F.; Scala, M.; Bruno, C.; Fiorillo, C. Congenital myopathy associated with a novel mutation in MEGF10 gene, myofibrillar alteration and progressive course. Acta Myol. 2022, 41, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Rose, D.U.; Ronci, S.; Caoci, S.; Maddaloni, C.; Diodato, D.; Catteruccia, M.; Fattori, F.; Bosco, L.; Pro, S.; Savarese, I.; et al. Vocal Cord Paralysis and Feeding Difficulties as Early Diagnostic Clues of Congenital Myasthenic Syndrome with Neonatal Onset: A Case Report and Review of Literature. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajkowski, E.J.; Kravath, R.E. Bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis in the newborn infant: Treatment with nasal continous positive airway pressure. Chest 1979, 75, 392–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, O.; Nimri, R.; Katz, Y.; Birk, E.; Vidne, B. Bilateral diaphragm paralysis following cardiac surgery in children: 10-Years’ experience. Intensive Care Med. 2006, 32, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simansky, D.A.; Paley, M.; Refaely, Y.; Yellin, A. Diaphragm plication following phrenic nerve injury: A comparison of paediatric and adult patients. Thorax 2002, 57, 613–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denamur, S.; Chenouard, A.; Lefort, B.; Baron, O.; Neville, P.; Baruteau, A.; Joram, N.; Chantreuil, J.; Bourgoin, P. Outcome analysis of a conservative approach to diaphragmatic paralysis following congenital cardiac surgery in neonates and infants: A bicentric retrospective study. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2021, 33, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizeq, Y.K.; Many, B.T.; Vacek, J.C.; Reiter, A.J.; Raval, M.V.; Abdullah, F.; Goldstein, S.D. Diaphragmatic paralysis after phrenic nerve injury in newborns. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, S.; Alexson, C.; Manning, J. Bilateral phrenic nerve paralysis after the Mustard procedure. Experience with four cases and recommendations for management. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1986, 92, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, B.C.; Graham, A.S.; Wetzel, R.; Newth, C.J.L. Respiratory inductance plethysmography used to diagnose bilateral diaphragmatic paralysis: A case report. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 5, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, T.S.; Montany, P.F. Thoracoscopic diaphragmatic plication. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. 1998, 8, 319–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.T.; Paterson, H.S. Mini-thoracotomy for diaphragmatic plication with thoracoscopic assistance. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1999, 68, 2364–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, V.V.; Lao, O.B.; Abdessalam, S.F. Laparoscopic transperitoneal repair of pediatric diaphragm eventration using an endostapler device. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2013, 23, 808–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Pan, W.; Zhou, Y. Thoracoscopic and laparoscopic plication of the hemidiaphragm is effective in the management of diaphragmatic eventration. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2014, 30, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, A.L.; Tchoe, H.J.; Shin, H.W.; Shin, C.M.; Lim, C.M. Assisted Breathing with a Diaphragm Pacing System: A Systematic Review. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, C.E.; Matalon, S.V.; Thompson, T.R.; Demuth, S.; Loew, J.M.; Liu, H.M.; Mastri, A.; Burke, B. Central hypoventilation syndrome: Experience with bilateral phrenic nerve pacing in 3 neonates. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1978, 118, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DiMarco, A.F. Diaphragm Pacing. Clin. Chest Med. 2018, 39, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Patient n 1 | Patient n 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M |

| Gestational age | 37 + 5 | 40 + 1 |

| Mode of delivery | Operative delivery due to shoulder dystocia | Vaginal delivery |

| APGAR score | 0, 3, 6 (perinatal asphyxia) | 9, 10 |

| Others features | Left humerus fracture BP involvment | Macrosomic, macrocephalic |

| Fluoroscopic evaluation | Inadequate bilateral diaphragm excursion | Reduced diaphragmatic excursion |

| Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) | Bilateral activity, with reduced left-sided response | Not performed |

| Electromyography (EMG) | Moderate peripheral neurogenic injury, affecting the C5–C6 roots on the right side, with signs of reinnervation but no active denervation | Normal EMG of the diaphragm |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Normal root courses of brachial plexus bilaterally | Normal MRI of the brain and spinal cord |

| Genetic | Exome analysis was negative | Paternal uniparental disomy (UPD) of chromosome 20 + A de novo heterozygous missense variant c.2983C > T in the SYNGAP1 gene |

| Treatment | Bilateral diaphragmatic plication at 45 days of age | Tracheostomy at 2 months of life |

| Follow up | Normal at 2 years, with physiotherapy and speech rehabilitation | Tracheostomy tube occluded at 2 years of life. Mild walking delay |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ronci, S.; Maddaloni, C.; Caoci, S.; Pro, S.; Longo, D.; Conforti, A.; Dotta, A.; Campi, F. Two Rare Cases of Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis in Neonates. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060127

Ronci S, Maddaloni C, Caoci S, Pro S, Longo D, Conforti A, Dotta A, Campi F. Two Rare Cases of Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis in Neonates. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(6):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060127

Chicago/Turabian StyleRonci, Sara, Chiara Maddaloni, Stefano Caoci, Stefano Pro, Daniela Longo, Andrea Conforti, Andrea Dotta, and Francesca Campi. 2025. "Two Rare Cases of Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis in Neonates" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 6: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060127

APA StyleRonci, S., Maddaloni, C., Caoci, S., Pro, S., Longo, D., Conforti, A., Dotta, A., & Campi, F. (2025). Two Rare Cases of Bilateral Diaphragmatic Paralysis in Neonates. Pediatric Reports, 17(6), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17060127