Measuring Vitality and Depletion During Adolescence: Validation of the Subjective Vitality/Subjective Depletion Scale in a Sample of Italian Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

| Original Version | Italian Version | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Vitality | Item 1 | I feel alive and vital | Mi sento pieno/a di vita |

| Item 2 | I have a lot of positive energy and initiative | Ho molta energia positiva e iniziativa | |

| Item 3 | I feel a sense of liveliness and spark | Mi sento vivo/a e attivo/a | |

| Subjective Depletion | Item 4 | I seem to have lost my “get up and go” | Mi sento di aver perso la mia “voglia di fare” |

| Item 5 | I feel drained | Mi sento svuotato/a | |

| Item 6 | I feel lifeless and unenthused | Mi sento spento/a e senza entusiasmo |

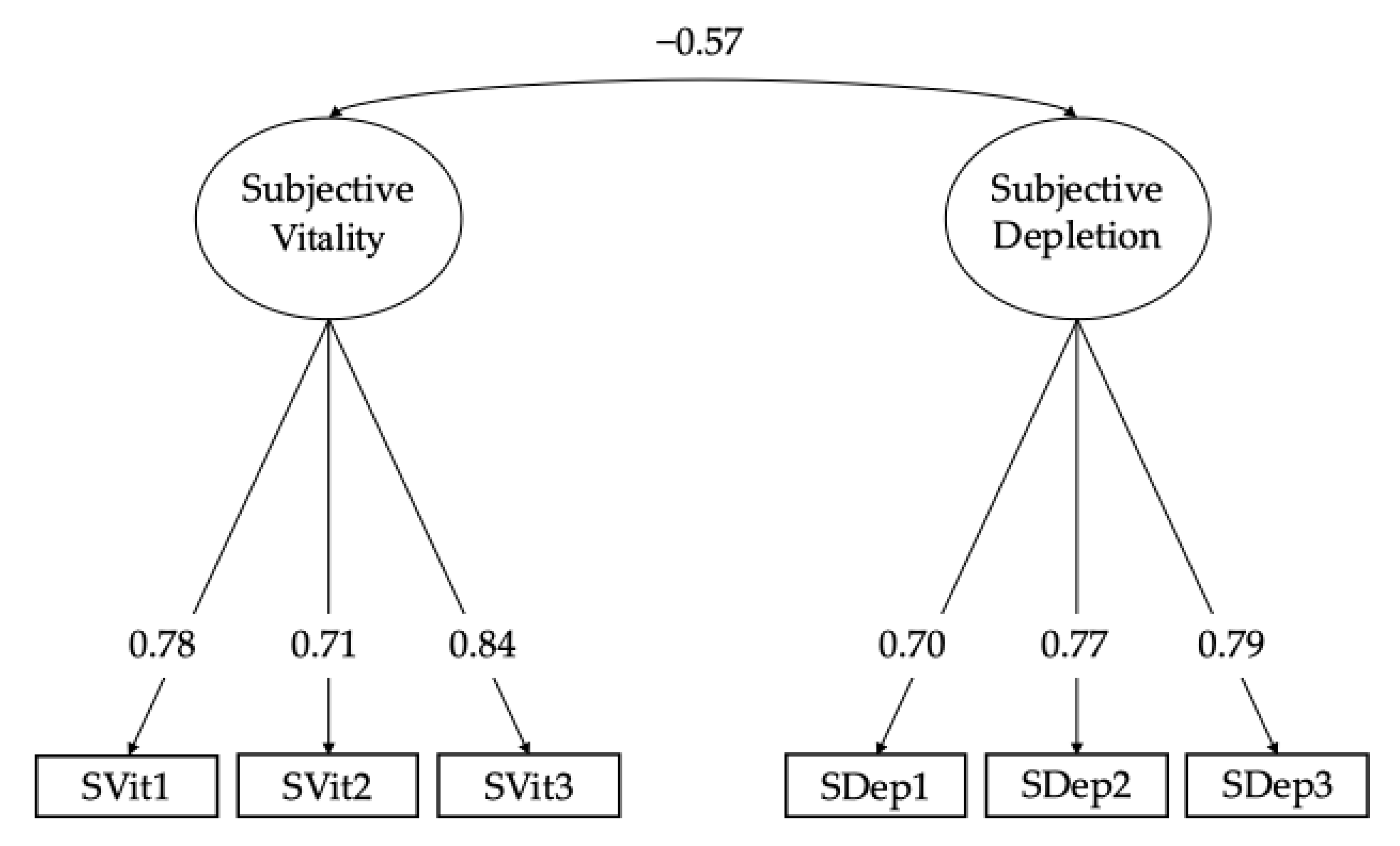

| Factor Loadings 95% CI | Standard Error | Residual Variance (95% CIs) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Vitality | Item 1 | 0.74–0.82 | 0.021 | 0.39 (0.33–0.45) |

| Item 2 | 0.67–0.75 | 0.024 | 0.49 (0.43–0.56) | |

| Item 3 | 0.81–0.87 | 0.018 | 0.29 (0.23–0.35) | |

| Subjective Depletion | Item 4 | 0.66–0.74 | 0.024 | 0.51 (0.44–0.57) |

| Item 5 | 0.72–0.81 | 0.026 | 0.42 (0.34–0.50) | |

| Item 6 | 0.74–0.83 | 0.027 | 0.38 (0.29–0.46) | |

| Factor correlation 95% CI | Standard error | |||

| SV with SD | −0.65–−0.49 | 0.041 |

| Subjective Vitality | Subjective Depletion | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median | IRQ | 25° | 75° | Mean (SD) | Median | IRQ | 25° | 75° | |

| Males | 3.58 (0.93) | 3.67 | 1.33 | 3.00 | 4.33 | 2.02 (0.98) | 2.00 | 1.67 | 1.00 | 2.67 |

| Females | 3.19 (0.93) | 3.00 | 1.33 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 2.16 (0.94) | 2.00 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 2.67 |

| Early adolescents | 3.50 (0.93) | 3.33 | 1.33 | 3.00 | 4.33 | 1.99 (0.91) | 1.67 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 2.67 |

| Adolescents | 3.36 (0.96) | 3.33 | 1.33 | 2.67 | 4.00 | 2.16 (1.00) | 2.00 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 2.67 |

References

- Steinberg, L. Cognitive and Affective Development in Adolescence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005, 9, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, R.A. Adolescent Psychosocial, Social, and Cognitive Development. Pediatr. Rev. 2013, 34, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sales, J.M.; Irwin, C.E., Jr. A Biopsychosocial Perspective of Adolescent Health and Disease. In Handbook of Adolescent Health Psychology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 13–29. ISBN 9781461466338. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C. On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-Being. J. Pers. 1997, 65, 529–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frederick, C.; Ryan, R.M. The Energy behind Human Flourishing: Theory and Research on Subjective Vitality. In The Oxford Handbook of Self-Determination Theory; Ryan, R.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, T.; Vaylay, S.; Kracke-Bock, J. Subjective Vitality: A Benefit of Self-Directed, Leisure Time Physical Activity. J. Happiness Stud. 2022, 23, 2903–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturan-Ilker, G. Psychological Well-Being and Motivation in a Turkish Physical Education Context. Educ. Psychol. Pract. 2014, 30, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Cutre, D.; Sicilia, Á. The Importance of Novelty Satisfaction for Multiple Positive Outcomes in Physical Education. Eur. Phys Educ. Rev. 2019, 25, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, P.L.; Hirsch, J.K.; Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.; Moynihan, J.A. Components of Sleep Quality as Mediators of the Relation Between Mindfulness and Subjective Vitality Among Older Adults. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.E.; DiPlacido, J. Vitality as a Mediator Between Diet Quality and Subjective Wellbeing Among College Students. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 1617–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Monagas, E.; Núñez, J.L.; Loro, J.F.; Moreno-Murcia, J.A.; León, J. What Makes a Student Feel Vital? Links between Teacher-Student Relatedness and Teachers’ Engaging Messages. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2023, 38, 1201–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinek, D.; Zumbach, J.; Carmignola, M. How Much Pressure Do Students Need to Achieve Good Grades?—The Relevance of Autonomy Support and School-Related Pressure for Vitality, Contentment with, and Performance in School. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, P.; Paixão, P.; Lens, W.; Lacante, M.; Luyckx, K. The Portuguese Validation of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale: Concurrent and Longitudinal Relations to Well-Being and Ill-Being. Psychol. Belg. 2016, 56, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Torres, A.P.; Tristán, J.; López-Walle, J.M.; González-Gallegos, A.; Pappous, A.; Tomás, I. Students’ Perceptions of Teachers’ Corrective Feedback, Basic Psychological Needs and Subjective Vitality: A Multilevel Approach. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 558954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, J.; Liew, J. Profiles of Adolescents’ Peer and Teacher Relatedness: Differences in Well-Being and Academic Achievement across Latent Groups. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2017, 54, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saricam, H. Mediating Role of Self Efficacy on the Relationship between Subjective Vitality and School Burnout in Turkish Adolescents. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2015, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Koçak, A.; Hepdarcan, I.; Mumcu, Y.; Apuhan, S.; Şensöz, B. The Mediating Role of Needs Frustration in Relation between Adolescent Triangulation and Adjustment. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 9432–9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, F.; Nunes, L.D.; Deng, Y.; Levesque-Bristol, C. Basic Psychological Needs as a Predictor of Positive Affects: A Look at Peace of Mind and Vitality in Chinese and American College Students. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020, 15, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, A.; Michou, A.; Vassiou, A. Adolescents’ Autonomous Functioning and Implicit Theories of Ability as Predictors of Their School Achievement and Week-to-Week Study Regulation and Well-Being. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 48, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Muraven, M.; Tice, D.M. Ego Depletion: Is the Active Self a Limited Resource? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moller, A.C.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Choice and Ego-Depletion: The Moderating Role of Autonomy. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2006, 32, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.D.; Chung, P.K. Factor Structure and Measurement Invariance of the Subjective Vitality Scale: Evidence from Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; Guilford Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata, M.; Yamazaki, F.; Guo, D.W.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D. Advancement of the Subjective Vitality Scale: Examination of Alternative Measurement Models for Japanese and Singaporeans. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, P.; Paixão, P.; Lens, W.; Lacante, M.; Sheldon, K. Factor Structure and Dimensionality of the Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs among Portuguese High School Students. Relations to Well-Being and Ill-Being. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2016, 47, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Monagas, E.; Núñez, J.L. Predicting Students’ Basic Psychological Need Profiles through Motivational Appeals: Relations with Grit and Well-Being. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2022, 97, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alivernini, F. An Exploration of the Gap between Highest and Lowest Ability Readers across 20 Countries. Educ. Stud. 2013, 39, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.J.; Mills, K.L. Is Adolescence a Sensitive Period for Sociocultural Processing? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steare, T.; Gutiérrez Muñoz, C.; Sullivan, A.; Lewis, G. The Association between Academic Pressure and Adolescent Mental Health Problems: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 339, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Bianchi, D.; Biasi, V.; Lucidi, F.; Girelli, L.; Cozzolino, M.; Alivernini, F. Social Inclusion of Immigrant Children at School: The Impact of Group, Family and Individual Characteristics, and the Role of Proficiency in the National Language. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2023, 27, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratelle, C.F.; Duchesne, S. Trajectories of Psychological Need Satisfaction from Early to Late Adolescence as a Predictor of Adjustment in School. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 39, 388–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletta, A.; Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S. Leadership for Learning: The Relationships between School Context, Principal Leadership and Mediating Variables. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2017, 31, 98–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Kang, Q.; Bi, C.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Wu, D. Are Fathers More Important? The Positive Association Between the Parent-Child Relationship and Left-Behind Adolescents’ Subjective Vitality. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2023, 32, 3612–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanski, A. The Pursuit of Health: A Vitality Based Perspective. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2023, 77, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. From Ego Depletion to Vitality: Theory and Findings Concerning the Facilitation of Energy Available to the Self. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadieh, H.; Khamesan, A. A Serial Mediation Model of Perceived Social Class and Cyberbullying: The Role of Subjective Vitality in Friendship Relations and Psychological Distress. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2025, 20, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, K.S.; Kim, S.; Korpela, K.M.; Song, M.K.; Lee, G.; Jeong, Y. Evaluating the Reliability and Validity of the Children’s Vitality-Relaxation Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Sharma, A.; Rani, R. Effect of Age and Gender on Subjective Vitality of Adults. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 11, 214–218. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz, H. Estimation and Comparison of Latent Means Across Cultures. In Cross-Cultural Analysis: Methods and Applications; Schmidt, P., Davidov, E., Billiet, J., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 85–116. [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, W. Measurement Invariance, Factor Analysis and Factorial Invariance. Psychometrika 1993, 58, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) PISA 2012 Technical Report. Programme for International Student Assessment. OECD Publishing. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/PISA-2012-technical-report-final.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Dawe, J.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Palombi, T.; Frederick, C.M.; Chirico, A.; Lucidi, F.; Alivernini, F. Measuring Subjective Vitality and Depletion in Older People from a Self-Determination Theory Perspective: A Dual Country Study. Exp. Aging Res. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Test Commission International Guidelines for Test Use. Int. J. Test. 2001, 1, 93–114. [CrossRef]

- Eccles, D.W. The Think Aloud Method: What Is It and How Do I Use It? Qual. Res. Sport. Exerc. Health 2017, 9, 514–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchiolo, E.; Manganelli, S.; Lucidi, F.; Alivernini, F. Measuring Emotional Well-Being at School Among Students With Different Characteristics: A Population Study. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalanobis, P.C. On the Generalised Distance in Statistics. Proc. Natl. Inst. Sci. India 1936, 2, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Daat Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education International: Upper saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mardia, K.V. Measures of Multivariate Skewness and Kurtosis with Applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P. A Scaled Difference Chi-Square Test Statistic for Moment Structure Analysis. Psychometrika 2001, 66, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structure Models. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.Y. Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes; University of California, Los Angeles: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, D.R.; Sauer, P.L.; Young, M. Composite Reliability in Structural Equations Modeling. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1995, 55, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R.M. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 09, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. Likert Scales, Levels of Measurement and the “Laws” of Statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.K.; Muthén, B.O. Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Mplus: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2019.

- Olivoto, T.; Lúcio, A.D.C. Metan: An R Package for Multi-Environment Trial Analysis. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Enviroment for Statistical Computing.; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Bertrams, A.; Dyllick, T.H.; Englert, C.; Krispenz, A. German Adaptation of the Subjective Vitality Scales (SVS-G). Open Psychol. 2020, 2, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbeck, F.; Hautzinger, M.; Wolkenstein, L. Validation of the German Version of the Subjective Vitality Scale—A Cross-Sectional Study and a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Well-Being Assess. 2019, 3, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M.; Ryan, R.M.; Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A.; Antolín-Suárez, L.; Brenning, K.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Oliva, A. On Psychological Growth and Vulnerability: Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration as a Unifying Principle. J. Psychother. Integr. 2020, 23, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, S.R.; Taylor, I.M.; Meijen, C.; Passfield, L. Young Adolescent Psychological Need Profiles: Associations with Classroom Achievement and Well-Being. Psychol. Sch. 2019, 56, 1004–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavilidi, M.F.; Mason, C.; Leahy, A.A.; Kennedy, S.G.; Eather, N.; Hillman, C.H.; Morgan, P.J.; Lonsdale, C.; Wade, L.; Riley, N.; et al. Effect of a Time-Efficient Physical Activity Intervention on Senior School Students’ On-Task Behaviour and Subjective Vitality: The ‘Burn 2 Learn’ Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 299–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canby, N.K.; Cameron, I.M.; Calhoun, A.T.; Buchanan, G.M. A Brief Mindfulness Intervention for Healthy College Students and Its Effects on Psychological Distress, Self-Control, Meta-Mood, and Subjective Vitality. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D.J.; Kim, L.E.; Glandorf, H.L. Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2024, 39, 931–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarkar, Z.M.; Ghasemi, M.B.; Manesh, E.M.M.; Sarvestani, M.M.M.; Moghbeli, N.M.; Rostamipoor, N.M.; Seifi, Z.; Ardakani, M.M.B. The Effectiveness of Adolescent-Oriented Mindfulness Training on Academic Burnout and Social Anxiety Symptoms in Students: Experimental Research. Ann. Med. Surg. 2023, 85, 2683–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalipay, M.J.N.; King, R.B.; Cai, Y. Autonomy Is Equally Important across East and West: Testing the Cross-Cultural Universality of Self-Determination Theory. J. Adolesc. 2020, 78, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Levesque-Bristol, C.; Maeda, Y. General Need for Autonomy and Subjective Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis of Studies in the US and East Asia. J. Happiness Stud. 2018, 19, 1863–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.B.; Haw, J.Y.; Wang, Y. Need-Support Facilitates Well-Being across Cultural, Economic, and Political Contexts: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Learn. Instr. 2024, 93, 101978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Lehmus-Sun, A.; Parker, P.D.; Pessi, A.B.; Ryan, R.M. Needs and Well-Being Across Europe: Basic Psychological Needs Are Closely Connected with Well-Being, Meaning, and Symptoms of Depression in 27 European Countries. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2023, 14, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item Content | Mean | SD | Sk | Ku |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel alive and vital (SVit) | 3.32 | 1.13 | −0.16 | −0.67 |

| 2. I have a lot of positive energy and initiative (SVit) | 3.29 | 1.13 | −0.18 | −0.67 |

| 3. I feel a sense of liveliness and spark (SVit) | 3.47 | 1.12 | −0.26 | −0.71 |

| 4. I seem to have lost my “get up and go” (SDep) | 2.32 | 1.19 | 0.66 | −0.45 |

| 5. I feel drained (SDep) | 1.98 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 0.40 |

| 6. I feel lifeless and unenthused (SDep) | 2.04 | 1.12 | 0.99 | 0.29 |

| Biological sex 1 | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | Δχ2 | ΔRMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔSRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configural model | 9.899 | 16 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.011 | - | - | - | - |

| Metric model | 14.859 | 20 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.022 | 5.198 | 0 | 0 | -0.01 |

| Scalar model | 30,901 | 26 | 0.018 | 0.997 | 0.036 | 17.679 | −0.018 | −0.003 | −0.014 |

| Age groups 2 | χ2 | df | RMSEA | CFI | SRMR | Δχ2 | ΔRMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔSRMR |

| Configural model | 10.002 | 16 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.013 | - | - | - | - |

| Metric model | 15.733 | 20 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.025 | 6.255 | 0 | 0 | −0.012 |

| Scalar model | 27.914 | 26 | 0.012 | 0.999 | 0.048 | 14.015 | −0.012 | −0.001 | −0.023 |

| Subjective Vitality (95%CIs) | Subjective Depletion (95%CIs) | Cohen’s d Vitality | Cohen’s d Depletion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Sex | ||||

| Female a vs. Male | 0.393 *** (0.264–0.501) | −0.116 (−0.240–0.009) | 0.46 | - |

| Age groups | ||||

| Early adolescents b vs. Adolescents | −0.202 ** (−0.324–−0.080) | 0.166 ** (0.043–0.289) | −0.23 | 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raimondi, G.; Zacchilli, M.; Frederick, C.M.; Alivernini, F.; Manganelli, S.; Cavicchiolo, E.; Lucidi, F.; Palombi, T.; Chirico, A.; Dawe, J. Measuring Vitality and Depletion During Adolescence: Validation of the Subjective Vitality/Subjective Depletion Scale in a Sample of Italian Students. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050098

Raimondi G, Zacchilli M, Frederick CM, Alivernini F, Manganelli S, Cavicchiolo E, Lucidi F, Palombi T, Chirico A, Dawe J. Measuring Vitality and Depletion During Adolescence: Validation of the Subjective Vitality/Subjective Depletion Scale in a Sample of Italian Students. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(5):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050098

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaimondi, Giulia, Michele Zacchilli, Christina M. Frederick, Fabio Alivernini, Sara Manganelli, Elisa Cavicchiolo, Fabio Lucidi, Tommaso Palombi, Andrea Chirico, and James Dawe. 2025. "Measuring Vitality and Depletion During Adolescence: Validation of the Subjective Vitality/Subjective Depletion Scale in a Sample of Italian Students" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 5: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050098

APA StyleRaimondi, G., Zacchilli, M., Frederick, C. M., Alivernini, F., Manganelli, S., Cavicchiolo, E., Lucidi, F., Palombi, T., Chirico, A., & Dawe, J. (2025). Measuring Vitality and Depletion During Adolescence: Validation of the Subjective Vitality/Subjective Depletion Scale in a Sample of Italian Students. Pediatric Reports, 17(5), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050098