Parent but Not Peer Attachment Mediates the Relations Between Childhood Poverty and Rural Adolescents’ Internalizing Problem Behaviors

Abstract

1. Introduction

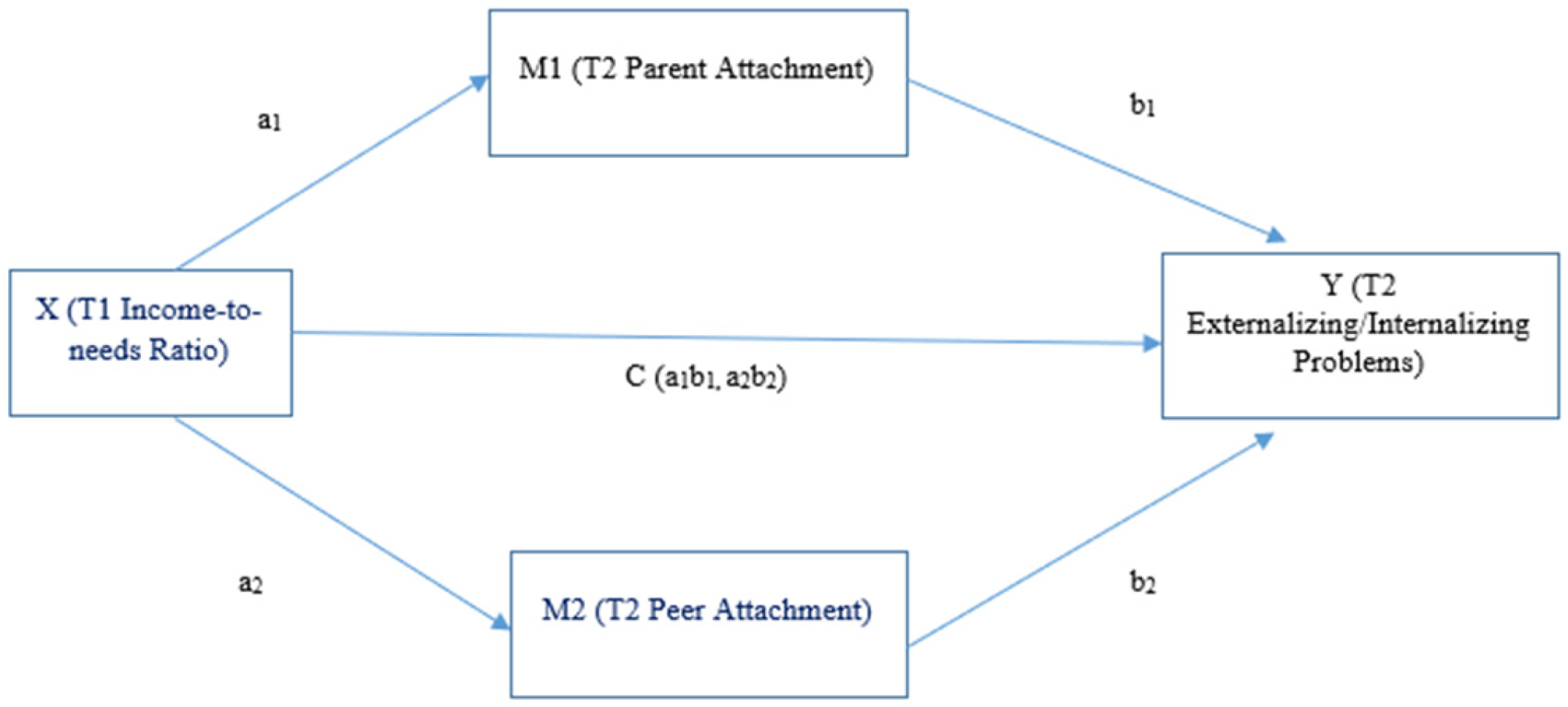

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.2. Relationship Processes: Family Poverty, Attachment Security, and Youth Behavior

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Measures

3. Results

3.1. Data Analysis Plan

3.2. Primary Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Creamer, J.; Shrider, E.A.; Burns, K.; Chen, F. Poverty in the United States: 2021. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2022/demo/p60-277.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, H.; Aber, J.L.; Beardslee, W.R. The effects of poverty on the mental, emotional, and behavioral health of children and youth: Implications for prevention. Am. Psychol. 2012, 67, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, G.W. Childhood poverty and adult psychological well-being. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14949–14952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robinson, L.R.; Holbrook, J.R.; Bitsko, R.H.; Hartwig, S.A.; Kaminski, J.W.; Ghandour, R.M.; Peacock, G.; Heggs, A.; Boyle, C.A. Differences in health care, family, and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders among children aged 2–8 years in rural and urban areas—United States, 2011–2012. Surveill. Summ. 2017, 66, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazza, J.R.; Pingault, J.-B.; Booij, L.; Boivin, M.; Tremblay, R.; Lambert, J.; Zunzunegui, M.V.; Côté, S. Poverty and behavior problems during early childhood: The mediating role of maternal depression symptoms and parenting. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2016, 41, 670–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Placa, V.; Corlyon, J. Unpacking the Relationship between Parenting and Poverty: Theory, Evidence and Policy. Soc. Policy Soc. 2016, 15, 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth, M.E.; Evans, G.W.; Grant, K.; Carter, J.S.; Duffy, S. Poverty and the development of psychopathology. In Developmental Psychopathology, 3rd ed.; Cicchetti, D., Ed.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan, C.; Zeifman, D. Sex and the psychological tether. In Attachment Processes in Adulthood; Bartholomew, K., Perlman, D., Eds.; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1994; pp. 151–178. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, L.; Morris, A.S. Adolescent development. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J. Resilience in midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Negrão, M.; Soares, I.; Mesman, J. Predicting harsh discipline in at-risk mothers: The moderating effect of socioeconomic deprivation severity. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 725–733. [Google Scholar]

- Cuartas, J.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.; Ma, J.; Castillo, B. Civil conflict, domestic violence, and poverty as predictors of corporal punishment in Colombia. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 90, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highlander, A.; Zachary, C.; Jenkins, K.; Loiselle, R.; McCall, M.; Youngstrom, J.; McKee, L.G.; Forehand, R.; Jones, D.J. Clinical Presentation and Treatment of Early-Onset Behavior Disorders: The Role of Parent Emotion Regulation, Emotion Socialization, and Family Income. Behav. Modif. 2021, 46, 1047–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nievar, M.A.; Luster, T. Developmental processes in African American families: An application of McLoyd’s theoretical model. J. Marriage Fam. 2006, 68, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Elder, G.H., Jr. Families in Trouble Times: Adapting to Change in Rural America; de Gruyter: Hawthorne, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, E. The economic side of social relations: Household poverty, adolescents’ own resources and peer relations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 23, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmiedeberg, C.; Schumann, N. Poverty and adverse peer relationships among children in Germany: A longitudinal study. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 1717–1733. [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W.M.; Dirks, M.; Infantino, E.; Delay, D. Principles for studying contextual variations in peer experiences: Rules for peer radicals. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.K.; Wang, Z.; Wong, H.; Tang, V. Child deprivation as a mediator of the relationship between family poverty, bullying victimization, and psychological distress. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 2001–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-K.; Wang, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-W. Social relationships as mediators of material deprivation, school bullying victimization, and subjective well-being among children across 25 countries: A global and cross-national perspective. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 2415–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S. Psychological well-being and distress in adolescents: An investigation into associations with poverty, peer victimization, and self-esteem. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 194824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss. Vol. 1: Attachment; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, L.; Goldberg, S.; Vaishali, R.; Pederson, D.; Benoit, D.; Moran, G.; Poulton, L.; Myhal, N.; Zwiers, M.; Gleason, K.; et al. On the relation between maternal state of mind and sensitivity in the prediction of infant attachment security. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wolff, M.S.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Sensitivity and attachment: A meta-analysis on parental antecedents of infant attachment. Child Dev. 1997, 68, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumariu, L.E. Parent-child attachment and emotion regulation. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2015, 148, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P. Structure and functions of internal working models of attachment and their role in emotion regulation. Attach. Hum. Dev. 1999, 1, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hazan, C.; Campa, M. (Eds.) Human Bonding: The Science of Affectional Ties; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. The emerging field of adolescent romantic relationships. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 11, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, C.; Zeifman, D. Pair bonds as attachments: Evaluating the evidence. In Handbook of Attachment: Theory, Research, and Clinical Application; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P.R., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 336–354. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, N.L.; Kobak, R. Assessing adolescents’ attachment hierarchies: Differences across developmental periods and associations with individual adaptation. J. Res. Adolesc. 2010, 20, 678–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laible, D. Attachment with parents and peers in late adolescence: Links with emotional competence and social behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Khan, W.; Amin, F.; Khan, M.F. Influence of Parenting Styles and Peer Attachment on Life Satisfaction Among Adolescents: Mediating Role of Self-Esteem. Fam. J. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.H.; Heinzer, J.E.; Miller, A.L.; Zimmerman, M.A. Transitions in friendship attachment during adolescence are associated with developmental trajectories of depression through adulthood. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; Tan, J. The multiple facts of attachment in adolescence. In Handbook of Attachment, 3rd ed.; Cassidy, J., Shaver, P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield, J.; Humphrey, N.; Hebron, J. The role of parental and peer attachment relationships and school connectedness in predicting adolescent mental health outcomes. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2016, 21, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawatlal, N.; Pillay, B.J.; Kliewer, W. Socioeconomic status, family-related variables, and caregiver-adolescent attachment. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2015, 45, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wambua, G.N.; Obondo, A.; Bifulco, A.; Kumar, M. The role of attachment relationship in adolescents’ problem behavior development: A cross-sectional study of Kenyan adolescents in Nairobi city. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2018, 12, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.P.; McElhaney, K.B.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Jodl, K.M. Stability and change in attachment security across adolescence. Child Dev. 2004, 75, 1792–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armsden, G.C.; Greenberg, M.T. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 1987, 16, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, C.S.; Martini, P.S.; Zavattini, G.C. The factor structure of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA): A survey of Italian adolescents. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T. Child Behavior Checklist; University Medical Education Associates: Burlington, VT, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, H.; Liu, S.; Miao, D.; Yuan, Y. Sample size determination of mediation analysis of longitudinal data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Ansari, A.; Peng, P. Reconsidering the relation between parental functioning and child externalizing behaviors: A meta-analysis on child-driven effects. J. Fam. Psychol. 2021, 35, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van IJzendoorn, M.; Schuengel, C.; Wang, Q.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. Improving parenting, child attachment, and externalizing behaviors: Meta-analysis of the first 25 randomized controlled trials on the effects of Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting and Sensitive Discipline. Dev. Psychopathol. 2023, 35, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongers, I.L.; Koot, H.M.; Der Ende, J.V.; Verhulst, F.C. Developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 2024, 75, 1523–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholte, R.H.; Van Aken, M.A. Peer relations in adolescence. In Handbook of Adolescent Development; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2020; pp. 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gorrese, A.; Ruggieri, R. Peer attachment: A meta-analytic review of gender and age differences and associations with parent attachment. J. Youth Adolesc. 2012, 41, 650–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nickerson, A.; Nagle, R.J. The influence of parent and peer attachments on life satisfaction in middle childhood and early adolescence. In Quality-of-Life Research on Children and Adolescents; Dannerbeck, A., Casas, F., Sadurni, M., Coenders, G., Eds.; Social indicators Research Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, J.P.; Grande, L.; Tan, J.; Loeb, E. Parent and peer predictors of change in attachment security from adolescence to adulthood. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupéré, V.; Goulet, M.; Archambault, I.; Dion, E.; Leventhal, T.; Crosnoe, R. Circumstances preceding dropout among rural high school students: A comparison with urban peers. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2019, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Gristy, C. The central importance of peer relationships for student engagement and well being in a rural secondary school. Pastor. Care Educ. 2012, 30, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sherman, J.; Sage, R. Sending off all your good treasures: Rural Schools, brain-drain, and community survival in the wake of economic collapse. J. Res. Rural Educ. 2011, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Millings, A.; Buck, R.; Montgomery, A.; Spears, M.; Stallard, P. School connectedness, peer attachment, and self-esteem as predictors of adolescent depression. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, R.; Williams, S.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Martin, J.; Kawachi, I. Participation in clubs and groups from childhood to adolescence and its effects on attachment and self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2006, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksek, D.A.; Solakoglu, O. The relative influence of parental attachment, peer attachment, school attachment, and school alienation on delinquency among high school students in Turkey. Deviant Behav. 2016, 37, 723–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.B. Best friend attachment versus peer attachment in the prediction of adolescent psychological adjustment. J. Adolesc. 2010, 33, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar, A.B.; Sutton, T.E.; Simons, L.G.; Wickrama, K.A.S. Romantic relationship transitions and changes in health among rural, White young adults. J. Fam. Psychol. 2016, 30, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, G.R.; Bolin, J.N.; Gamm, L.D. Rural health people 2010, 2020, and beyond: The need goes on. Fam. Community Health 2011, 34, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiser, R.; Helmerhorst, K.O.W.; Gelderen, L.v.R. Perceived quality of the mother-adolescent and father-adolescent attachment relationship and adolescents’ self-esteem. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | |||||||||

| 2. Ethnicity | −0.10 | - | ||||||||

| 3. Age T1 | −0.07 | 0.10 | - | |||||||

| 4. Externalizing Problems T1 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.10 | - | ||||||

| 5. Internalizing Problems T1 | 0.13 † | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.69 *** | - | |||||

| 6. Income-to-needs T1 | 0.00 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.26 *** | −0.19 *** | - | ||||

| 7. Parent Attachment T2 | −0.18 ** | 0.16 * | −0.02 | −0.32 *** | −0.33 *** | 0.23 ** | - | |||

| 8. Peer Attachment T2 | 0.22 ** | 0.02 | −0.12 | −0.30 *** | −0.25 *** | 0.09 | 0.42 *** | - | ||

| 9. Externalizing Problems T2 | 0.09 | −0.04 | 0.07 | 0.59 *** | 0.33 *** | −0.19 ** | −0.32 *** | −0.29 *** | - | |

| 10. Internalizing Problems T2 | 0.30 *** | −0.12 † | −0.00 | 0.39 *** | 0.41 *** | −0.03 | −0.45 *** | −0.28 *** | 0.55 *** | - |

| M | 0.49 | 0.86 | 13.37 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 2.34 | 103.64 | 96.97 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| SD | 0.50 | 0.35 | 1.00 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 1.44 | 17.82 | 15.96 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Consequent | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Effect IV on M1-PA | Effect IV on M2-PR | Direct Effect on Y | Indirect Effect on Y | ||||||

| β | p | Β | p | β | p | Boot B | Boot SE | CI Lower | CI Upper | |

| Y = T2 externalizing, R2 = 0.42 | ||||||||||

| X (T1 income-to-needs ratio) | 1.51 | 0.096 | 0.19 | 0.817 | −0.001 | 0.599 | ||||

| M1-PA | - | - | - | - | −0.002 | 0.029 | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.058 | 0.001 |

| M1-PR | - | - | - | - | −0.002 | 0.172 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.020 | 0.016 |

| Gender | −5.99 | 0.016 | 7.53 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.567 | ||||

| Ethnicity | −0.03 | 0.781 | −0.10 | 0.269 | −0.00 | 0.647 | ||||

| Age | 9.64 | 0.039 | 3.01 | 0.474 | −0.07 | 0.215 | ||||

| T1 externalizing | −20.40 | <0.001 | −19.18 | <0.001 | 0.50 | <0.001 | ||||

| Y = T2 internalizing, R2 = 0.35 | ||||||||||

| X (T1 income-to-needs ratio) | 1.79 | 0.044 | 0.51 | 0.527 | 0.01 | 0.228 | ||||

| M1-PA | - | - | - | - | −0.004 | <0.001 | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.097 | −0.003 |

| M1-PR | - | - | - | - | −0.002 | 0.057 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.034 | 0.016 |

| Gender | −4.81 | 0.057 | 8.53 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.017 | ||||

| Ethnicity | −0.05 | 0.657 | −0.12 | 0.196 | −0.00 | 0.682 | ||||

| Age | 10.08 | 0.031 | 3.30 | 0.436 | −0.08 | 0.172 | ||||

| T1 internalizing | −20.22 | <0.001 | −17.47 | <0.001 | 0.31 | <0.001 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Song, Q.; Whipple, S.S.; Doan, S.N.; Cassells, R.C.; Evans, G.W. Parent but Not Peer Attachment Mediates the Relations Between Childhood Poverty and Rural Adolescents’ Internalizing Problem Behaviors. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050097

Song Q, Whipple SS, Doan SN, Cassells RC, Evans GW. Parent but Not Peer Attachment Mediates the Relations Between Childhood Poverty and Rural Adolescents’ Internalizing Problem Behaviors. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(5):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050097

Chicago/Turabian StyleSong, Qingfang, Sara S. Whipple, Stacey N. Doan, Rochelle C. Cassells, and Gary W. Evans. 2025. "Parent but Not Peer Attachment Mediates the Relations Between Childhood Poverty and Rural Adolescents’ Internalizing Problem Behaviors" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 5: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050097

APA StyleSong, Q., Whipple, S. S., Doan, S. N., Cassells, R. C., & Evans, G. W. (2025). Parent but Not Peer Attachment Mediates the Relations Between Childhood Poverty and Rural Adolescents’ Internalizing Problem Behaviors. Pediatric Reports, 17(5), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17050097