Validation of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS)-Related Pediatric Treatment Evaluation Checklist (PTEC)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Validation

2.3. Test–Retest Reliability

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Measurements

2.6. Compliance with Ethical Standards

3. Results

3.1. Participants

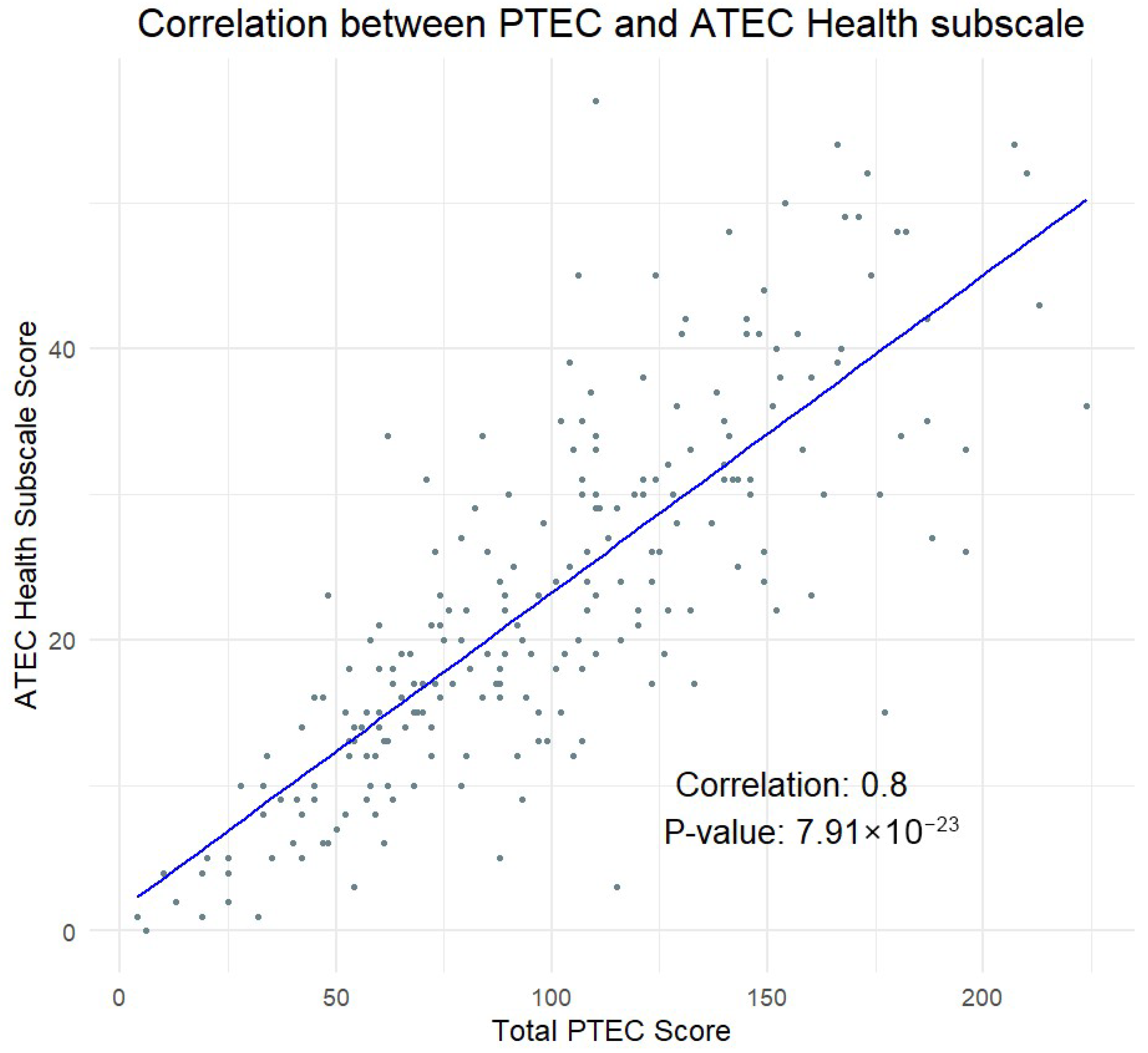

3.2. Validity

3.3. Reliability

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gagliano, A.; Carta, A.; Tanca, M.G.; Sotgiu, S. Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Current Perspectives. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2023, 19, 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.K.; Gerardi, D.M.; Leckman, J.F. Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome. Psychiatr. Clin. 2014, 37, 353–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thienemann, M.; Murphy, T.; Leckman, J.; Shaw, R.; Williams, K.; Kapphahn, C.; Frankovich, J.; Geller, D.; Bernstein, G.; Chang, K.; et al. Clinical Management of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Part I—Psychiatric and Behavioral Interventions. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2017, 27, 566–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedo, S.E.; Leckman, J.F.; Rose, N.R. From research subgroup to clinical syndrome: Modifying the PANDAS criteria to describe PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome). Pediatr Ther. 2012, 2, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankovich, J.; Thienemann, M.; Pearlstein, J.; Crable, A.; Brown, K.; Chang, K. Multidisciplinary Clinic Dedicated to Treating Youth with Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome: Presenting Characteristics of the First 47 Consecutive Patients. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swedo, S.E. Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS). Mol. Psychiatry 2002, 7, S24–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, M.S.C.; de Sousa Filho, L.F.; Rabello, P.M.; Santiago, B.M. International Classification of Diseases–11th revision: From design to implementation. Rev. Saúde Pública 2020, 54, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallanti, S.; Di Ponzio, M. PANDAS/PANS in the COVID-19 age: Autoimmunity and Epstein–Barr virus reactivation as trigger agents? Children 2023, 10, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarello, F.; Spitoni, S.; Hollander, E.; Matucci Cerinic, M.; Pallanti, S. An expert opinion on PANDAS/PANS: Highlights and controversies. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2017, 21, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.E.; Rincon, N.; McCarty, P.J.; Brister, D.; Scheck, A.C.; Rossignol, D.A. Biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 197, 106520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanca, M.G. Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS): New Insights. 2021. Available online: https://tesidottorato.depositolegale.it/handle/20.500.14242/71125 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Scahill, L.; Riddle, M.A.; McSwiggin-Hardin, M.; Ort, S.I.; King, R.A.; Goodman, W.K.; Cicchetti, D.; Leckman, J.F. Children’s Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: Reliability and validity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, M.; Jakubovski, E.; Fremer, C.; Dietrich, A.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Jäger, B.; Müller-Vahl, K.R.; Group, E.C. Yale global tic severity scale (YGTSS): Psychometric quality of the gold standard for tic assessment based on the large-scale EMTICS study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 626459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimland, B.; Edelson, S.M. Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC); Autism Research Institute: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; Available online: http://www.autism.com (accessed on 1 January 2014).

- Vreeland, A.; Calaprice, D.; Or-Geva, N.; Frye, R.E.; Agalliu, D.; Lachman, H.M.; Pittenger, C.; Pallanti, S.; Williams, K.; Ma, M.; et al. Postinfectious Inflammation, Autoimmunity, and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Sydenham Chorea, Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infection, and Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Disorder. Dev. Neurosci. 2023, 45, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Backer, N.B. Correlation between Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) and Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) in the evaluation of autism spectrum disorder. Sudan. J. Paediatr. 2016, 16, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Geier, D.A.; Kern, J.K.; Geier, M.R. A comparison of the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) and the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) for the quantitative evaluation of autism. J. Ment. Health Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2013, 6, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarusiewicz, B. Efficacy of Neurofeedback for Children in the Autistic Spectrum: A Pilot Study. J. Neurother. 2002, 6, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Vyshedksy, D.; Martinez, S.; Kannel, B.; Braverman, J.; Edelson, S.M.; Vyshedskiy, A. Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) norms: A “growth chart” for ATEC score changes as a function of age. Children 2018, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Khokhlovich, E.; Martinez, S.; Kannel, B.; Edelson, S.M.; Vyshedskiy, A. Epidemiological Study of Autism Subgroups Using Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC) Score. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2020, 50, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netson, R.; Schmiedel Fucks, A.; Schmiedel Sanches Santos, A.; Poloni, L.E.P.; Nacano, N.N.; Fucks, E.; Radi, K.; Strong, W.E.; Carnaval, A.A.; Russo, M. A Comparison of Parent Reports, the Mental Synthesis Evaluation Checklist (MSEC) and the Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist (ATEC), with the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, J.; Dunn, R.; Vyshedskiy, A. Development of the Mental Synthesis Evaluation Checklist (MSEC): A Parent-Report Tool for Mental Synthesis Ability Assessment in Children with Language Delay. Children 2018, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, S.; Phung, D.; Duong, T.; Greenhill, S.; Adams, B. TOBY: Early intervention in autism through technology. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LO, USA, 26 April–1 May 2025; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 3187–3196. Available online: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2466437 (accessed on 1 March 2017).

- Vyshedskiy, A.; Khokhlovich, E.; Dunn, R.; Faisman, A.; Elgart, J.; Lokshina, L.; Gankin, Y.; Ostrovsky, S.; deTorres, L.; Edelson, S.M. Novel prefrontal synthesis intervention improves language in children with autism. Healthcare 2020, 8, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.K.; Patel, P.D.; McGuire, J.F.; Kennel, A.; Mutch, P.J.; Parker-Athill, E.C.; Hanks, C.E.; Lewin, A.B.; Storch, E.A.; Toufexis, M.D.; et al. Characterization of the Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Phenotype. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromark, C.; Harris, R.A.; Wickström, R.; Horne, A.; Silverberg-Mörse, M.; Serlachius, E.; Mataix-Cols, D. Establishing a Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Clinic: Baseline Clinical Features of the Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Cohort at Karolinska Institutet. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 625–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Fernell, E.; Preda, I.; Wallin, L.; Fasth, A.; Gillberg, C.; Gillberg, C. Paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome in children and adolescents: An observational cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2019, 3, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankovich, J.; Leibold, C.M.; Farmer, C.; Sainani, K.; Kamalani, G.; Farhadian, B.; Willett, T.; Park, J.M.; Sidell, D.; Ahmed, S. The burden of caring for a child or adolescent with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS): An observational longitudinal study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2018, 80, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromark, C.; Hesselmark, E.; Djupedal, I.G.; Silverberg, M.; Horne, A.; Harris, R.A.; Serlachius, E.; Mataix-Cols, D. A Two-to-Five Year Follow-Up of a Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome Cohort. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2022, 53, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, E.E.; Miles, K.; Schlenk, N.; Manko, C.; Ma, M.; Farhadian, B.; Chang, K.; Silverman, M.; Thienemann, M.; Frankovich, J. Defining clinical course of patients evaluated for pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome (PANS): Phenotypic classification based on 10 years of clinical data. Dev. Neurosci. 2025, 47, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Visscher, C.; Hesselmark, E.; Rautio, D.; Djupedal, I.G.; Silverberg, M.; Nordström, S.I.; Serlachius, E.; Mataix-Cols, D. Measuring clinical outcomes in children with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome: Data from a 2–5 year follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Subscale/Item | |

|---|---|---|

| I. Behavior/Mood | ||

| 1 | 1 | Rages |

| 2 | 2 | School refusal |

| 3 | 3 | Uncooperative or resistant |

| 4 | 4 | Oppositional behavior |

| 5 | 5 | Disagreeable/non-compliant |

| 6 | 6 | Temper tantrums |

| 7 | 7 | Shouts or screams |

| 8 | 8 | Insensitive to others’ feelings |

| 9 | 9 | Inappropriate laughing/crying |

| 10 | 10 | Disinhibited/impulsive |

| 11 | 11 | Avoids contact with others |

| 12 | 12 | Harms self |

| 13 | 13 | Irritable/agitated |

| 14 | 14 | Destructive to property |

| 15 | 15 | Verbal aggression |

| 16 | 16 | Physical aggression |

| 17 | 17 | Unhappy/crying |

| 18 | 18 | Depressed mood |

| 19 | 19 | No motivation/joy |

| 20 | 20 | Mood swings |

| II. OCD | ||

| 21 | 1 | Unwanted sexual thoughts |

| 22 | 2 | Violent/horrific intrusive images |

| 23 | 3 | Non-violent intrusive thoughts |

| 24 | 4 | Obsession/fear of germs |

| 25 | 5 | Washing/cleaning compulsions |

| 26 | 6 | Fear chemicals/solvents/contaminates |

| 27 | 7 | Fears harm will come to self |

| 28 | 8 | Fears hurting self/others |

| 29 | 9 | Fears will be responsible for aggressive/illegal behavior |

| 30 | 10 | Fear of blurting obscenities |

| 31 | 11 | Perfectionism |

| 32 | 12 | Checking or repeating obsessions/rituals |

| 33 | 13 | Counting rituals |

| 34 | 14 | Destructive to property |

| 35 | 15 | Confessing |

| 36 | 16 | Reassurance seeking |

| 37 | 17 | Obsessive speech |

| 38 | 18 | Repetitive speech |

| 39 | 19 | Rigid routines |

| 40 | 20 | Hoarding rituals |

| 41 | 21 | Magical thoughts/superstitious obsessions |

| 42 | 22 | Lucky/unlucky words, numbers, colors |

| 43 | 23 | Requires symmetry |

| 44 | 24 | Arranging obsessions |

| 45 | 25 | Obsession with order/location of objects |

| 46 | 26 | Need to tap or touch |

| 47 | 27 | Overly concerned with health |

| 48 | 28 | Requires another person to participate in OCD |

| III. Anxiety | ||

| 49 | 1 | Separation anxiety |

| 50 | 2 | Irrational or amplified fears |

| 51 | 3 | Avoids leaving home |

| 52 | 4 | Anxious about being around people |

| 53 | 5 | General/other anxiety |

| IV. Food intake | ||

| 54 | 1 | Food refusal/anorexia |

| 55 | 2 | Limited fluid intake |

| 56 | 3 | Picky eating |

| 57 | 4 | Negative body image |

| 58 | 5 | Limited due to choking fear |

| 59 | 6 | Limited due to fear of vomiting |

| 60 | 7 | Limited due to contamination fear |

| 61 | 8 | Urge to overeat |

| V. Tics | ||

| 62 | 1 | Vocal tics |

| 63 | 2 | Motor tics |

| VI. Cognitive/Developmental | ||

| 64 | 1 | Memory issues |

| 65 | 2 | Brain fog |

| 66 | 3 | Stutters |

| 67 | 4 | Baby talk |

| 68 | 5 | Gross motor regression (tripping/coordination issues) |

| 69 | 6 | Fine motor: difficulty with/regression handwriting/art |

| 70 | 7 | Difficulty with/regression math skills |

| VII. Sensory | ||

| 71 | 1 | Sound-sensitive |

| 72 | 2 | Light-sensitive |

| 73 | 3 | Sensitive to smells |

| 74 | 4 | Sensitive to textures |

| 75 | 5 | Other sensory sensitivities |

| 76 | 6 | Amplified sensory seeking |

| VIII. Other | ||

| 77 | 1 | Hallucinations |

| 78 | 2 | Delusions |

| 79 | 3 | Paranoia |

| 80 | 4 | Suicidal ideation |

| 81 | 5 | Homicidal ideation |

| 82 | 6 | Attention issues |

| 83 | 7 | Hyperactivity |

| 84 | 8 | Daytime urinary frequency |

| 85 | 9 | Daytime wetting/soiling |

| 86 | 10 | Lacks friends |

| 87 | 11 | Dilated pupils |

| IX. Sleep | ||

| 88 | 1 | Nightmares |

| 89 | 2 | Night terrors |

| 90 | 3 | Problems falling asleep |

| 91 | 4 | Problems staying asleep |

| 92 | 5 | Bedwetting |

| X. Health | ||

| 93 | 1 | Constipation |

| 94 | 2 | Diarrhea |

| 95 | 3 | Acute infection |

| 96 | 4 | Fatigued |

| 97 | 5 | Lethargic |

| 98 | 6 | Pain in stomach |

| 99 | 7 | Pain in head |

| 100 | 8 | Pain in joints |

| 101 | 9 | Pain other |

| Number of Participants | Percent of Total | Age, Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PANS, PANDAS, or Other inflammatory brain disorder | 204 | 91 | 15.6 (8.0) |

| PANS | 135 | 59 | 16.0 (8.5) |

| PANDAS | 91 | 40 | 14.1 (6.2) |

| Other inflammatory brain disorder | 50 | 22 | 18.7 (7.3) |

| Undiagnosed | 25 | 11 | 16.1 (13.0) |

| Number of Participants | Percent of Total | Age, Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A Strep exposure without infection | 23 | 10 | 14.8 (10.8) |

| Group A Strep confirmed infection | 48 | 21 | 13.8 (7.3) |

| COVID-19 | 36 | 16 | 17.8 (10.1) |

| Influenza | 22 | 10 | 12.7 (5.3) |

| Viral infection (other) | 60 | 27 | 14.7 (8.3) |

| Bacterial infection (other) | 53 | 24 | 16.0 (8.9) |

| Allergen exposure | 21 | 9 | 18.5 (10.7) |

| Unknown | 87 | 37 | 16.5 (8.5) |

| # | Item | Item–Total Correlation | Alpha If Item Deleted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Behavior/Mood | 1 | 1 | Rages | 0.56 | 0.96 |

| 2 | 2 | School refusal | 0.58 | 0.96 | |

| 3 | 3 | Uncooperative or resistant | 0.59 | 0.96 | |

| 4 | 4 | Oppositional behavior | 0.59 | 0.96 | |

| 5 | 5 | Disagreeable/non-compliant | 0.59 | 0.96 | |

| 6 | 6 | Temper tantrums | 0.56 | 0.96 | |

| 7 | 7 | Shouts or screams | 0.58 | 0.96 | |

| 8 | 8 | Insensitive to others’ feelings | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 9 | 9 | Inappropriate laughing/crying | 0.53 | 0.96 | |

| 10 | 10 | Disinhibited/impulsive | 0.49 | 0.96 | |

| 11 | 11 | Avoids contact with others | 0.51 | 0.96 | |

| 12 | 12 | Harms self | 0.42 | 0.96 | |

| 13 | 13 | Irritable/agitated | 0.63 | 0.96 | |

| 14 | 14 | Destructive to property | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 15 | 15 | Verbal aggression | 0.55 | 0.96 | |

| 16 | 16 | Physical aggression | 0.55 | 0.96 | |

| 17 | 17 | Unhappy/crying | 0.63 | 0.96 | |

| 18 | 18 | Depressed mood | 0.62 | 0.96 | |

| 19 | 19 | No motivation/joy | 0.59 | 0.96 | |

| 20 | 20 | Mood swings | 0.66 | 0.96 | |

| II. OCD | 21 | 1 | Unwanted sexual thoughts | 0.4 | 0.96 |

| 22 | 2 | Violent/horrific intrusive images | 0.5 | 0.96 | |

| 23 | 3 | Non-violent intrusive thoughts | 0.52 | 0.96 | |

| 24 | 4 | Obsession/fear of germs | 0.39 | 0.96 | |

| 25 | 5 | Washing/cleaning compulsions | 0.34 | 0.96 | |

| 26 | 6 | Fear chemicals/solvents/contaminates | 0.36 | 0.96 | |

| 27 | 7 | Fears harm will come to self | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 28 | 8 | Fears hurting self/others | 0.43 | 0.96 | |

| 29 | 9 | Fears will be responsible for aggressive/illegal behavior | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 30 | 10 | Fear of blurting obscenities | 0.42 | 0.96 | |

| 31 | 11 | Perfectionism | 0.41 | 0.96 | |

| 32 | 12 | Checking or repeating obsessions/rituals | 0.47 | 0.96 | |

| 33 | 13 | Counting rituals | 0.37 | 0.96 | |

| 34 | 14 | Destructive to property | 0.43 | 0.96 | |

| 35 | 15 | Confessing | 0.37 | 0.96 | |

| 36 | 16 | Reassurance seeking | 0.49 | 0.96 | |

| 37 | 17 | Obsessive speech | 0.56 | 0.96 | |

| 38 | 18 | Repetitive speech | 0.48 | 0.96 | |

| 39 | 19 | Rigid routines | 0.53 | 0.96 | |

| 40 | 20 | Hoarding rituals | 0.43 | 0.96 | |

| 41 | 21 | Magical thoughts/superstitious obsessions | 0.39 | 0.96 | |

| 42 | 22 | Lucky/unlucky words, numbers, colors | 0.33 | 0.96 | |

| 43 | 23 | Requires symmetry | 0.4 | 0.96 | |

| 44 | 24 | Arranging obsessions | 0.37 | 0.96 | |

| 45 | 25 | Obsession with order/location of objects | 0.47 | 0.96 | |

| 46 | 26 | Need to tap or touch | 0.35 | 0.96 | |

| 47 | 27 | Overly concerned with health | 0.36 | 0.96 | |

| 48 | 28 | Requires another person to participate in OCD | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| III. Anxiety | 49 | 1 | Separation anxiety | 0.61 | 0.96 |

| 50 | 2 | Irrational or amplified fears | 0.68 | 0.96 | |

| 51 | 3 | Avoids leaving home | 0.54 | 0.96 | |

| 52 | 4 | Anxious about being around people | 0.59 | 0.96 | |

| 53 | 5 | General/other anxiety | 0.69 | 0.96 | |

| IV. Food intake | 54 | 1 | Food refusal/anorexia | 0.5 | 0.96 |

| 55 | 2 | Limited fluid intake | 0.38 | 0.96 | |

| 56 | 3 | Picky eating | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 57 | 4 | Negative body image | 0.33 | 0.96 | |

| 58 | 5 | Limited due to choking fear | 0.24 | 0.96 | |

| 59 | 6 | Limited due to fear of vomiting | 0.42 | 0.96 | |

| 60 | 7 | Limited due to contamination fear | 0.41 | 0.96 | |

| 61 | 8 | Urge to overeat | 0.19 | 0.96 | |

| V. Tics | 62 | 1 | Vocal tics | 0.34 | 0.96 |

| 63 | 2 | Motor tics | 0.39 | 0.96 | |

| VI. Cognitive/Developmental | 64 | 1 | Memory issues | 0.45 | 0.96 |

| 65 | 2 | Brain fog | 0.56 | 0.96 | |

| 66 | 3 | Stutters | 0.26 | 0.96 | |

| 67 | 4 | Baby talk | 0.28 | 0.96 | |

| 68 | 5 | Gross motor regression (tripping/coordination issues) | 0.42 | 0.96 | |

| 69 | 6 | Fine motor: difficulty with/regression handwriting/art | 0.48 | 0.96 | |

| 70 | 7 | Difficulty with/regression math skills | 0.51 | 0.96 | |

| VII. Sensory | 71 | 1 | Sound-sensitive | 0.56 | 0.96 |

| 72 | 2 | Light-sensitive | 0.48 | 0.96 | |

| 73 | 3 | Sensitive to smells | 0.51 | 0.96 | |

| 74 | 4 | Sensitive to textures | 0.49 | 0.96 | |

| 75 | 5 | Other sensory sensitivities | 0.41 | 0.96 | |

| 76 | 6 | Amplified sensory seeking | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| VIII. Other | 77 | 1 | Hallucinations | 0.42 | 0.96 |

| 78 | 2 | Delusions | 0.48 | 0.96 | |

| 79 | 3 | Paranoia | 0.58 | 0.96 | |

| 80 | 4 | Suicidal ideation | 0.35 | 0.96 | |

| 81 | 5 | Homicidal ideation | 0.33 | 0.96 | |

| 82 | 6 | Attention issues | 0.58 | 0.96 | |

| 83 | 7 | Hyperactivity | 0.51 | 0.96 | |

| 84 | 8 | Daytime urinary frequency | 0.46 | 0.96 | |

| 85 | 9 | Daytime wetting/soiling | 0.25 | 0.96 | |

| 86 | 10 | Lacks friends | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 87 | 11 | Dilated pupils | 0.54 | 0.96 | |

| IX. Sleep | 88 | 1 | Nightmares | 0.43 | 0.96 |

| 89 | 2 | Night terrors | 0.42 | 0.96 | |

| 90 | 3 | Problems falling asleep | 0.37 | 0.96 | |

| 91 | 4 | Problems staying asleep | 0.4 | 0.96 | |

| 92 | 5 | Bedwetting | 0.2 | 0.96 | |

| X. Health | 93 | 1 | Constipation | 0.36 | 0.96 |

| 94 | 2 | Diarrhea | 0.39 | 0.96 | |

| 95 | 3 | Acute infection | 0.47 | 0.96 | |

| 96 | 4 | Fatigued | 0.44 | 0.96 | |

| 97 | 5 | Lethargic | 0.45 | 0.96 | |

| 98 | 6 | Pain in stomach | 0.34 | 0.96 | |

| 99 | 7 | Pain in head | 0.41 | 0.96 | |

| 100 | 8 | Pain in joints | 0.48 | 0.96 | |

| 101 | 9 | Pain other | 0.43 | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vyshedskiy, A.; Conkey, A.; DeWeese, K.; Junghanns, F.B.; Adams, J.B.; Frye, R.E. Validation of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS)-Related Pediatric Treatment Evaluation Checklist (PTEC). Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040081

Vyshedskiy A, Conkey A, DeWeese K, Junghanns FB, Adams JB, Frye RE. Validation of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS)-Related Pediatric Treatment Evaluation Checklist (PTEC). Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(4):81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040081

Chicago/Turabian StyleVyshedskiy, Andrey, Anna Conkey, Kelly DeWeese, Frank Benno Junghanns, James B. Adams, and Richard E. Frye. 2025. "Validation of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS)-Related Pediatric Treatment Evaluation Checklist (PTEC)" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 4: 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040081

APA StyleVyshedskiy, A., Conkey, A., DeWeese, K., Junghanns, F. B., Adams, J. B., & Frye, R. E. (2025). Validation of Pediatric Acute-Onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS)-Related Pediatric Treatment Evaluation Checklist (PTEC). Pediatric Reports, 17(4), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040081