Disparities in Treatment Outcomes for Cannabis Use Disorder Among Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Study Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Treatment Outcomes for CUD

3.3. CUD Treatment Outcomes and Sample Characteristics in Bivariable Analysis

3.4. CUD Treatment Completion and Sample Characteristics in Multivariable Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, J.; Mejia, M.C.; Sacca, L.; Hennekens, C.H.; Kitsantas, P. Trends in marijuana use among adolescents in the United States. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrick, M.E.; Miech, R.A.; Johnston, L.D.; O’Malley, P.M. Monitoring the Future Panel Study Annual Report: National Data on Substance Use Among Adults Ages 19 to 60, 1976–2022; Monitoring the Future Monograph Series; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Harbor, MI, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; text rev.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawn, W.; Mokrysz, C.; Lees, R.; Trinci, K.; Petrilli, K.; Skumlien, M.; Borissova, A.; Ofori, S.; Bird, C.; Jones, G.; et al. The CannTeen Study: Cannabis use disorder, depression, anxiety, and psychotic-like symptoms in adolescent and adult cannabis users and age-matched controls. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 1350–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.H.; Caspi, A.; Cerdá, M.; Hancox, R.J.; Harrington, H.; Houts, R.; Poulton, R.; Ramrakha, S.; Thomson, W.M.; Moffitt, T.E. Associations between cannabis use and physical health problems in early midlife: A longitudinal comparison of persistent cannabis vs. tobacco users. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 75, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silins, E.; Horwood, L.J.; Patton, G.C.; Fergusson, D.M.; A Olsson, C.; Hutchinson, D.M.; Spry, E.; Toumbourou, J.W.; Degenhardt, L.; Swift, W.; et al. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: An integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, L.; Steinhoff, A.; Bechtiger, L.; Copeland, W.E.; Ribeaud, D.; Eisner, M.; Quednow, B.B. Frequent teenage cannabis use: Prevalence across adolescence and associations with young adult psychopathology and functional well-being in an urban cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021, 228, 109063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litt, M.D.; Kadden, R.M.; Tennen, H.; Petry, N.M. Individualized assessment and treatment program (IATP) for cannabis use disorder: Randomized controlled trial with and without contingency management. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2020, 34, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bobb, A.J.; Hill, K.P. Behavioral Interventions and Pharmacotherapies for Cannabis Use Disorder. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry 2014, 1, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mennis, J.; Stahler, G.J.; McKeon, T.P. Young adult cannabis use disorder treatment admissions declined as past month cannabis use increased in the U.S.: An analysis of states by year, 2008–2017. Addict. Behav. 2021, 123, 107049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA. Treatment Episode Data Set Discharges (TEDS-D) 2021: Public Use File (PUF) Codebook; Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0 [Computer Software]; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Principles of Adolescent Substance Use Disorder Treatment: A Research-Based Guide; National Institute on Drug Abuse: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2014. Available online: https://archives.nida.nih.gov/publications/principles-adolescent-substance-use-disorder-treatment-research-based-guide (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Kaminer, Y.; Ohannessian, C.M.; Burke, R.H. Adolescents with cannabis use disorders: Adaptive treatment for poor responders. Addict. Behav. 2017, 70, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.F.; Saha, T.D.; Ruan, W.J.; Goldstein, R.; Chou, S.P.; Jung, J.; Zhang, H.; Smith, S.M.; Pickering, R.P.; Huang, B.; et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 drug use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA Psychiatry 2016, 73, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Racial/ethnic Differences in Substance Use, Substance Use Disorders, and Substance Use Treatment Utilization Among People Aged 12 or Older (2015–2019); Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, S.S.; Segura, L.E.; Levy, N.S.; Mauro, P.M.; Mauro, C.M.; Philbin, M.M.; Hasin, D.S. Racial and ethnic differences in cannabis use following legalization in US states with medical cannabis laws. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2127002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Koh, K.A.; Hwang, S.W.; Wadhera, R.K. Mental health and substance use among homeless adolescents in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 327, 1820–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Z.; Mott, S.; Magwood, O.; Mathew, C.; Mclellan, A.; Kpade, V.; Gaba, P.; Kozloff, N.; Pottie, K.; Andermann, A. The impact of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA’s Center for the Application of Prevention Technologies. Preventing Youth Marijuana Use: Factors Associated with Use; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2017; Available online: https://solutions.edc.org/sites/default/files/Preventing-Youth-Marijuana-use-Factors-Associated-with-Use_0.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2024).

- Strashny, A. Age of substance use initiation among treatment admissions aged 18 to 30. In The CBHSQ Report; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M.; Baydala, L.; Khan, M.; Currie, C.; Morley, K.; Burkholder, C.; Davidson, R.; Stillar, A. Primary substance use prevention programs for children and youth: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e20192747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office of the Surgeon General. Chapter 3; Prevention programs and policies. In Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miech, R.A.; Johnston, L.D.; Patrick, M.E.; O’Malley, P.M.; Bachman, J.G.; Schulenberg, J.E. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2022: Secondary School Students; Monitoring the Future Monograph Series; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Harbor, MI, USA, 2023; Available online: https://monitoringthefuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/mtf2022.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Kitsantas, P.; Gimm, G.; Aljoudi, S.M. Treatment outcomes among pregnant women with cannabis use disorder. Addict. Behav. 2023, 144, 107723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Full Sample n (%) | Did Not Complete Treatment n = 25,324 (63.2%) n (%) | Completed Treatment n = 14,730 (36.8%) n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.082 | |||

| Male | 28,586 (71.4) | 71.7 | 70.9 | |

| Female | 11,460 (28.6) | 28.3 | 29.1 | |

| Age at admission | 0.523 | |||

| 12–14 years | 7467 (18.6) | 18.7 | 18.5 | |

| 15–17 years | 32,587 (81.4) | 81.3 | 81.5 | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 16,972 (43.4) | 44.8 | 41.1 | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 8943 (22.9) | 24.9 | 19.4 | |

| Hispanic | 8955 (22.9) | 21.2 | 25.8 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 723 (1.8) | 1.7 | 2.2 | |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific Islander | 1248 (3.2) | 1.8 | 5.6 | |

| Asian | 497 (1.3) | 1.0 | 1.8 | |

| Other | 1744 (4.5) | 4.7 | 4.1 | |

| Living arrangements | <0.001 | |||

| Homeless | 132 (0.4) | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| Dependent living | 22,646 (61.1) | 59.0 | 64.4 | |

| Independent living | 14,290 (38.6) | 40.6 | 35.3 | |

| Arrests in past 30 days | <0.001 | |||

| None | 34,304 (90.9) | 87.5 | 96.2 | |

| Once | 2749 (7.3) | 9.9 | 3.1 | |

| Two or more times | 705 (1.9) | 2.6 | 0.7 | |

| Age at first use of cannabis (years) | <0.001 | |||

| 11 years and under | 5691 (14.4) | 15.3 | 12.9 | |

| 12–14 | 23,258 (58.8) | 59.4 | 57.8 | |

| 15–17 | 10,615 (16.8) | 25.4 | 29.4 | |

| Co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 13,728 (37.4) | 41.3 | 30.3 | |

| No | 22,959 (62.6) | 58.7 | 69.7 | |

| Co-substance use at admission | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 13,633 (34.0) | 35.3 | 31.9 | |

| No | 26,421 (66.0) | 64.7 | 68.1 | |

| Referral source | <0.001 | |||

| Individual/self-referral | 7974 (20.3) | 20.9 | 19.2 | |

| Alcohol/drug use care provider | 1356 (3.5) | 4.3 | 2.0 | |

| Other health care provider | 5802 (14.8) | 14.6 | 15.1 | |

| School | 3866 (9.8) | 9.3 | 10.7 | |

| Employer/EAP | 596 (1.5) | 0.6 | 3.2 | |

| Other community referral | 4553 (11.6) | 12.1 | 10.7 | |

| Court/criminal justice | 15,128 (38.5) | 38.2 | 39.0 | |

| Treatment service/setting | <0.001 | |||

| Detox, 24 h, free-standing residential | 333 (0.8) | 0.8 | 0.9 | |

| Rehab/residential, short term (30 days or fewer) | 500 (3.7) | 3.4 | 4.4 | |

| Rehab/residential, long term (>30 days) | 3236 (8.1) | 7.3 | 9.5 | |

| Ambulatory, intensive outpatient | 6084 (15.2) | 15.4 | 14.8 | |

| Ambulatory, non-intensive outpatient | 28,883 (72.1) | 73.2 | 70.4 | |

| Length of stay | <0.001 | |||

| 1 month or less | 9876 (24.7) | 33.6 | 9.3 | |

| 2–3 months | 11,692 (29.2) | 28.5 | 30.3 | |

| 4–6 months | 11,298 (28.2) | 22.7 | 37.8 | |

| 7–12 months | 5513 (13.8) | 11.3 | 18.1 | |

| >12 months | 1675 (4.2) | 4.0 | 4.5 |

| Characteristics | Treatment Completion Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) |

| Female | Reference |

| Age at admission | |

| 12–14 years | 0.98 (0.93–1.04) |

| 15–17 years | Reference |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | Reference |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 0.79 (0.75–0.84) |

| Hispanic | 1.13 (1.08–1.18) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.12 (0.98–1.28) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander/Asian Pacific Islander | 2.31 (2.04–2.61) |

| Asian | 1.56 (1.31–1.86) |

| Other | 0.88 (0.79–0.96) |

| Living arrangements | |

| Homeless | 0.50 (0.35–0.73) |

| Dependent living | Reference |

| Independent living | 0.82 (0.79–0.86) |

| Arrests in the past 30 days | |

| None | Reference |

| Once | 0.33 (0.29–0.36) |

| Two or more times | 0.24 (0.19–0.29) |

| Age at first use of cannabis (years) | |

| 11 years and under | 0.66 (0.62–0.71) |

| 12–14 | 0.79 (0.75–0.83) |

| 15–17 | Reference |

| Co-occurring mental and substance use disorders | |

| Yes | 0.79 (0.77–0.84) |

| No | Reference |

| Co-substance use at admission | |

| Yes | 0.84 (0.81–0.88) |

| No | Reference |

| Referral source | |

| Individual/self-referral | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) |

| Alcohol/drug use care provider | 0.76 (0.68–0.84) |

| Other health care provider | 0.89 (0.84–0.95) |

| School | 1.16 (1.08–1.24) |

| Employer/EAP | 3.75 (3.06–4.59) |

| Other community referral | 0.86 (0.81–0.92) |

| Court/criminal justice | Reference |

| Treatment service/setting | |

| Detox, 24 h, free-standing residential | 2.89 (2.44–3.44) |

| Rehab/residential, short term (30 days or fewer) | 2.06 (1.88–2.25) |

| Rehab/residential, long term (>30 days) | 2.69 (2.50–2.90) |

| Ambulatory, intensive outpatient | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) |

| Ambulatory, non-intensive outpatient | Reference |

| Length of stay | |

| 1 month or less | 0.18 (0.17–0.21) |

| 2–3 months | 0.68 (0.61–0.75) |

| 4–6 months | 1.19 (1.08–1.32) |

| 7–12 months | 1.26 (1.13–1.39) |

| >12 months | Reference |

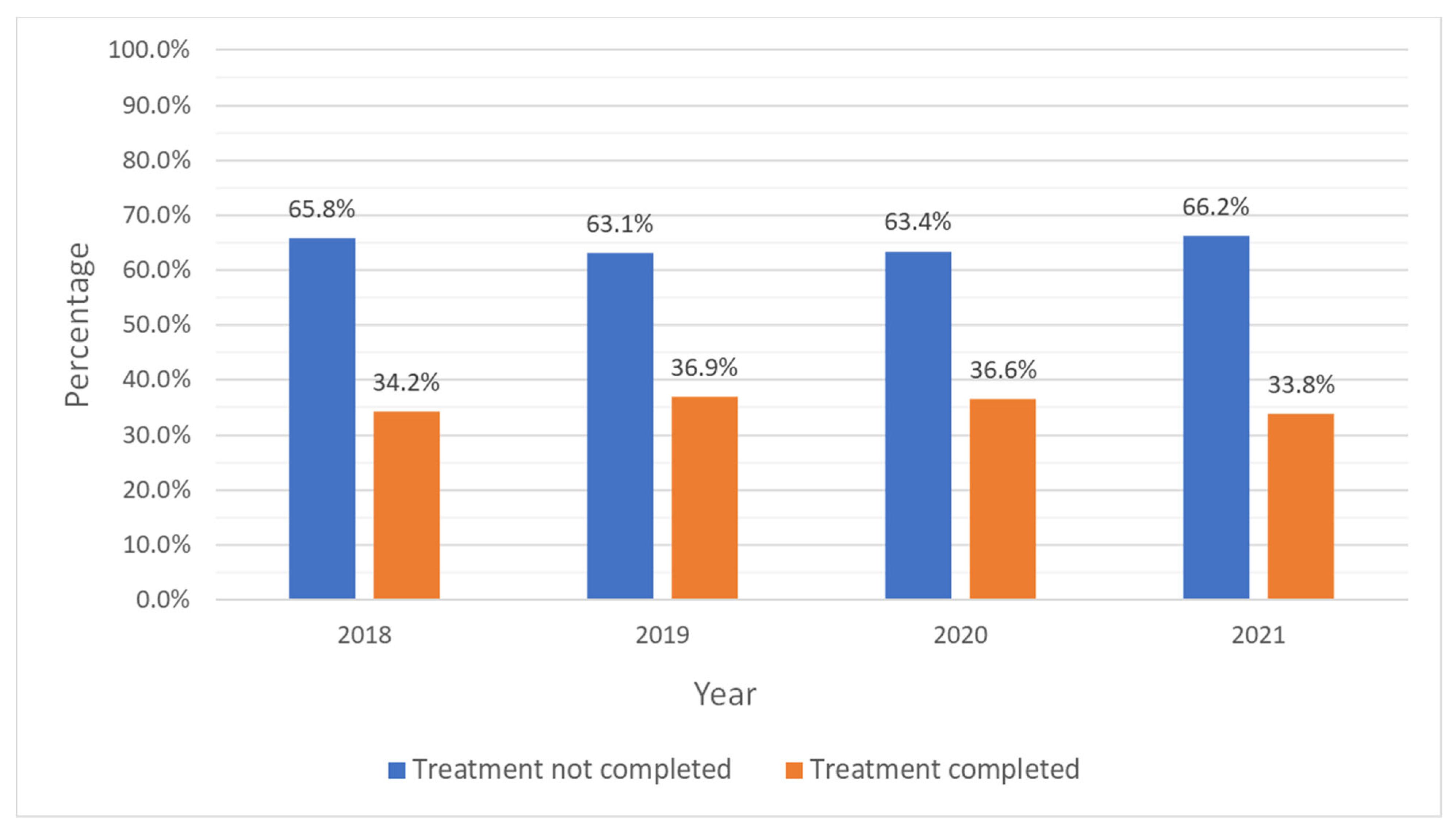

| Year of discharge | |

| 2018 | Reference |

| 2019 | 0.97 (0.93–1.02) |

| 2020 | 0.83 (0.79–0.88) |

| 2021 | 0.90 (0.85–0.96) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miranda, H.; Ostanin, J.; Shugar, S.; Mejia, M.C.; Sacca, L.; Doucette, M.L.; Hennekens, C.H.; Kitsantas, P. Disparities in Treatment Outcomes for Cannabis Use Disorder Among Adolescents. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040074

Miranda H, Ostanin J, Shugar S, Mejia MC, Sacca L, Doucette ML, Hennekens CH, Kitsantas P. Disparities in Treatment Outcomes for Cannabis Use Disorder Among Adolescents. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiranda, Helena, Jhon Ostanin, Simon Shugar, Maria Carmenza Mejia, Lea Sacca, Mitchell L. Doucette, Charles H. Hennekens, and Panagiota Kitsantas. 2025. "Disparities in Treatment Outcomes for Cannabis Use Disorder Among Adolescents" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040074

APA StyleMiranda, H., Ostanin, J., Shugar, S., Mejia, M. C., Sacca, L., Doucette, M. L., Hennekens, C. H., & Kitsantas, P. (2025). Disparities in Treatment Outcomes for Cannabis Use Disorder Among Adolescents. Pediatric Reports, 17(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17040074