Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating in Children: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

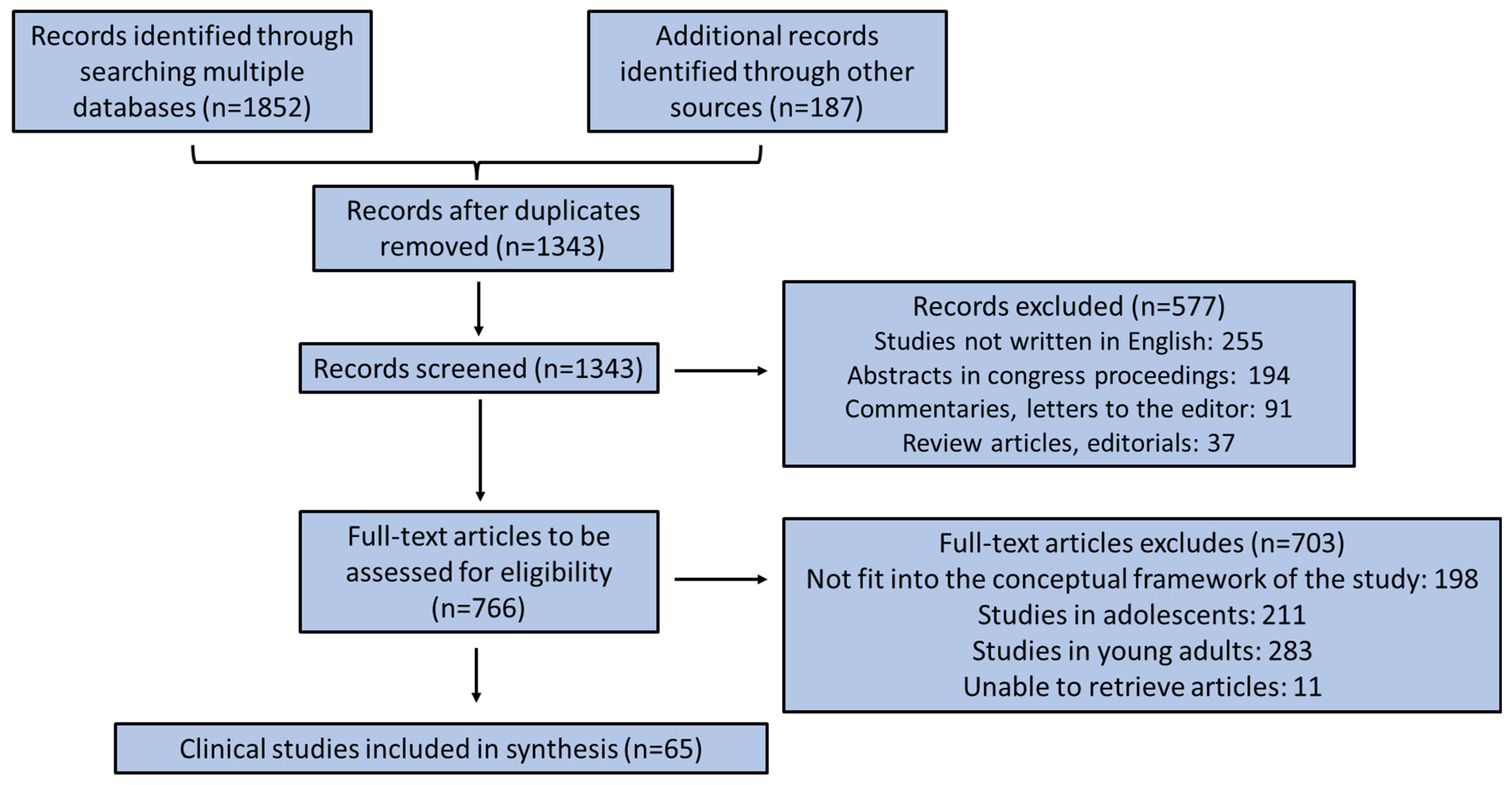

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Parental Behavior Effect on Children’s Emotional Eating

3.2. Association of Overweight and Obesity with Children’s Emotional Eating

3.3. Association of Mental Disorders with Children’s Emotional Eating

3.4. Associations of Children’s Dietary Habits with Emotional Eating

3.5. Other Factors Influencing Children’s Emotional Eating

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, J.; Ang, X.Q.; Giles, E.L.; Traviss-Turner, G. Emotional eating interventions for adults living with overweight or obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meye, F.J.; Adan, R.A. Feelings about food: The ventral tegmental area in food reward and emotional eating. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 35, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozkurt, O.; Çamli, A.; Kocaadam-Bozkurt, B. Factors affecting food addiction: Emotional eating, palatable eating motivations, and BMI. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 6841–6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, D.; Jones, A.; Keyworth, C.; Dhir, P.; Griffiths, A.; Shepherd, K.; Smith, J.; Traviss-Turner, G.; Matu, J.; Ells, L. Emotional eating interventions for adults living with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of behaviour change techniques. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 38, e13410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devonport, T.J.; Nicholls, W.; Fullerton, C. A systematic review of the association between emotions and eating behaviour in normal and overweight adult populations. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakanalis, A.; Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Papandreou, D.; Spanoudaki, M.; Vasios, G.K.; Pavlidou, E.; Mantzorou, M.; Giaginis, C. The association of emotional eating with overweight/obesity, depression, anxiety/stress, and dietary patterns: A review of the current clinical evidence. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnatowska, E.; Surma, S.; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, M. Relationship between mental health and emotional eating during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaner, G.; Yurtdaş-Depboylu, G.; Çalık, G.; Yalçın, T.; Nalçakan, T. Evaluation of perceived depression, anxiety, stress levels and emotional eating behaviours and their predictors among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 674–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, H.S.J.; Soong, R.Y.; Ang, W.H.D.; Ngooi, J.W.; Park, J.; Yong, J.Q.Y.O.; Goh, Y.S.S. The global prevalence of emotional eating in overweight and obese populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychol. 2025, 116, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, Z.E.; Bayrak, N.; Mengi Çelik, Ö.; Akkoca, M. The relationship between emotional eating, mindful eating, and depression in young adults. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 13, e4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, G.M.; Méjean, C.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Andreeva, V.A.; Bellisle, F.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. The associations between emotional eating and consumption of energy-dense snack foods are modified by sex and depressive symptomatology. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Strien, T.; Konttinen, H.; Homberg, J.R.; Engels, R.C.; Winkens, L.H. Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite 2016, 100, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bemanian, M.; Mæland, S.; Blomhoff, R.; Rabben, Å.K.; Arnesen, E.K.; Skogen, J.C.; Fadnes, L.T. Emotional Eating in Relation to Worries and Psychological Distress Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Population-Based Survey on Adults in Norway. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 18, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efe, Y.S.; Özbey, H.; Erdem, E.; Hatipoğlu, N. A comparison of emotional eating, social anxiety and parental attitude among adolescents with obesity and healthy: A case-control study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2020, 34, 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkuş, M.; Gelirgün, Ö.G.; Karataş, K.S.; Telatar, T.G.; Gökçen, O.; Dönmez, F. The Role of Anxiety and Depression in the Relationship Among Emotional Eating, Sleep Quality, and Impulsivity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2024, 212, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muha, J.; Schumacher, A.; Campisi, S.C.; Korczak, D.J. Depression and emotional eating in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite 2024, 200, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbers, C.A.; Summers, E. Emotional Eating and Weight Status in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantley, C.; Knol, L.L.; Douglas, J.W. Parental mindful eating practices and mindful eating interventions are associated with child emotional eating. Nutr. Res. 2023, 111, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutting, T.M.; Fisher, J.O.; Grimm-Thomas, K.; Birch, L.L. Like mother, like daughter: Familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers’ dietary disinhibition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetzmann, M.; Richter-Appelt, H.; Schulte-Markwort, M.; Schimmelmann, B.G. Associations among the perceived parent-child relationship, eating behavior, and body weight in preadolescents: Results from a community-based sample. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008, 33, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topham, G.L.; Hubbs-Tait, L.; Rutledge, J.M.; Page, M.C.; Kennedy, T.S.; Shriver, L.H.; Harrist, A.W. Parenting styles, parental response to child emotion, and family emotional responsiveness are related to child emotional eating. Appetite 2011, 56, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micali, N.; Simonoff, E.; Elberling, H.; Rask, C.U.; Olsen, E.M.; Skovgaard, A.M. Eating patterns in a population-based sample of children aged 5 to 7 years: Association with psychopathology and parentally perceived impairment. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2011, 32, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braden, A.; Rhee, K.; Peterson, C.B.; Rydell, S.A.; Zucker, N.; Boutelle, K. Associations between child emotional eating and general parenting style, feeding practices, and parent psychopathology. Appetite 2014, 80, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, N.; Sioen, I.; Michels, N.; Sleddens, E.; De Henauw, S. The influence of parenting style on health related behavior of children: Findings from the ChiBS study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Paxton, S.J.; McLean, S.A.; Campbell, K.J.; Wertheim, E.H.; Skouteris, H.; Gibbons, K. Maternal negative affect is associated with emotional feeding practices and emotional eating in young children. Appetite 2014, 80, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.C.; Holub, S.C. Emotion Regulation Feeding Practices Link Parents’ Emotional Eating to Children’s Emotional Eating: A Moderated Mediation Study. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, C.V.; Haycraft, E.; Blissett, J.M. Teaching our children when to eat: How parental feeding practices inform the development of emotional eating—A longitudinal experimental design. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 101, 908–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, C.A.; Christiansen, P.; Wilkinson, L.L. Using food to soothe: Maternal attachment anxiety is associated with child emotional eating. Appetite 2016, 99, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keitel-Korndörfer, A.; Bergmann, S.; Nolte, T.; Wendt, V.; von Klitzing, K.; Klein, A.M. Maternal mentalization affects mothers’—But not children’s—Weight via emotional eating. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2016, 18, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houldcroft, L.; Farrow, C.; Haycraft, E. Eating Behaviours of Preadolescent Children over Time: Stability, Continuity and the Moderating Role of Perceived Parental Feeding Practices. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, E.M.; Frankel, L.A.; Hernandez, D.C. The mediating role of child self-regulation of eating in the relationship between parental use of food as a reward and child emotional overeating. Appetite 2017, 113, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munsch, S.; Dremmel, D.; Kurz, S.; De Albuquerque, J.; Meyer, A.H.; Hilbert, A. Influence of Parental Expressed Emotions on Children’s Emotional Eating via Children’s Negative Urgency. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2017, 25, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Barker, E.D.; Llewellyn, C.; Fildes, A.; Wichstrøm, L. Emotional Feeding and Emotional Eating: Reciprocal Processes and the Influence of Negative Affectivity. Child Dev. 2018, 89, 1234–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derks, I.P.M.; Bolhuis, K.; Sijbrands, E.J.G.; Gaillard, R.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Jansen, P.W. Predictors and patterns of eating behaviors across childhood: Results from The Generation R study. Appetite 2019, 141, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, O.; Wichstrøm, L.; Llewellyn, C.H.; Steinsbekk, S. Emotional Over- and Undereating in Children: A Longitudinal Analysis of Child and Contextual Predictors. Child Dev. 2019, 90, e803–e818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nembhwani, H.V.; Winnier, J. Impact of problematic eating behaviour and parental feeding styles on early childhood caries. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2020, 30, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, N.; Mallan, K.M.; Byrne, R.; de Jersey, S.; Jansen, E.; Daniels, L.A. Non-responsive feeding practices mediate the relationship between maternal and child obesogenic eating behaviours. Appetite 2020, 151, 104648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, L.M.; Lammert, A.; Phelan, S.; Ventura, A.K. Associations between parenting stress, parent feeding practices, and perceptions of child eating behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appetite 2022, 177, 106148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.A.; Blissett, J.; Haycraft, E.; Farrow, C. Predicting preschool children’s emotional eating: The role of parents’ emotional eating, feeding practices and child temperament. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.A.; Haycraft, E.; Blissett, J.; Farrow, C. Preschool-aged children’s food approach tendencies interact with food parenting practices and maternal emotional eating to predict children’s emotional eating in a cross-sectional snalysis. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2022, 122, 1465–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnick, J.; Cardel, M.; Jones, L.; Gonzalez-Louis, R.; Janicke, D. Impact of mothers’ distress and emotional eating on calories served to themselves and their young children: An experimental study. Pediatr. Obes. 2022, 17, e12886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.R.; Chou, A.K.; Tseng, T.S. Association of maternal immigration status with emotional eating in Taiwanese children: The mediating roles of health literacy and feeding practices. Appetite 2025, 205, 107771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braet, C.; Van Strien, T. Assessment of emotional, externally induced and restrained eating behaviour in nine to twelve-year-old obese and non-obese children. Behav. Res. Ther. 1997, 35, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striegel-Moore, R.H.; Morrison, J.A.; Schreiber, G.; Schumann, B.C.; Crawford, P.B.; Obarzanek, E. Emotion-induced eating and sucrose intake in children: The NHLBI Growth and Health Study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 25, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, V.; Sinde, S.; Saxton, J.C. Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire: Associations with BMI in Portuguese children. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 100, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleddens, E.F.; Kremers, S.P.; Thijs, C. The children’s eating behaviour questionnaire: Factorial validity and association with Body Mass Index in Dutch children aged 6–7. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, L.; Hill, C.; Saxton, J.; Van Jaarsveld, C.H.; Wardle, J. Eating behaviour and weight in children. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, K.N.; Drewett, R.F.; Le Couteur, A.S.; Adamson, A.J.; Gateshead Milennium Study Core Team. Do maternal ratings of appetite in infants predict later Child Eating Behaviour Questionnaire scores and body mass index? Appetite 2010, 54, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haycraft, E.; Farrow, C.; Meyer, C.; Powell, F.; Blissett, J. Relationships between temperament and eating behaviours in young children. Appetite 2011, 56, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, J.C.; Carson, V.; Casey, L.; Boule, N. Examining behavioural susceptibility to obesity among Canadian pre-school children: The role of eating behaviours. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6, e501–e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, P.W.; Roza, S.J.; Jaddoe, V.W.; Mackenbach, J.D.; Raat, H.; Hofman, A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Tiemeier, H. Children’s eating behavior, feeding practices of parents and weight problems in early childhood: Results from the population-based Generation R Study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Tiemeier, H.; van der Ende, J.; Nijs, I.M.T.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Verhulst, F.C.; Jansen, P.W. Relation of emotional and behavioral problems with body mass index in preschool children: The Generation R Study. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2012, 33, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Paxton, S.J.; Massey, R.; Campbell, K.J.; Wertheim, E.H.; Skouteris, H.; Gibbons, K. Maternal feeding practices predict weight gain and obesogenic eating behaviors in young children: A prospective study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, O.; Kluckner, V.J.; Brandt, S.; Moss, A.; Weck, M.; Florath, I.; Wabitsch, M.; Hebebrand, J.; Schimmelmann, B.G.; Christiansen, H. Restrained and external-emotional eating patterns in young overweight children-results of the Ulm Birth Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- dos Passos, D.R.; Gigante, D.P.; Maciel, F.V.; Matijasevich, A. Children’s eating behaviour: Comparison between normal and overweight children from a school in Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Rev. Paul. Pediatr. 2015, 33, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Wichstrøm, L. Predictors of change in BMI from the age of 4 to 8. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, U.; Weisstaub, G.; Santos, J.L.; Corvalán, C.; Uauy, R. GOCS cohort: Children’s eating behavior scores and BMI. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalo, E.; Konttinen, H.; Vepsäläinen, H.; Chaput, J.P.; Hu, G.; Maher, C.; Maia, J.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Standage, M.; Tudor-Locke, C.; et al. Emotional eating, health behaviours, and obesity in children: A 12-country cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang Sim, D.E.; Strong, D.R.; Manzano, M.; Eichen, D.M.; Rhee, K.E.; Tanofsky-Kraff, M.; Boutelle, K.N. Evaluating psychometric properties of the Emotional Eating Scale Adapted for Children and Adolescents (EES-C) in a clinical sample of children seeking treatment for obesity: A case for the unidimensional model. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A.; Bhatia, H.P.; Sood, S.; Sharma, N.; Singh, A. Effect of perceived stress, BMI and emotional eating on dental caries in school-going children: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2022, 15 (Suppl. 2), S180–S185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S.T.; McClain, A.D.; Spruijt-Metz, D. Anxiety mediates the relationship between sleep onset latency and emotional eating in minority children. Eat. Behav. 2010, 11, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michels, N.; Sioen, I.; Braet, C.; Eiben, G.; Hebestreit, A.; Huybrechts, I.; Vanaelst, B.; Vyncke, K.; De Henauw, S. Stress, emotional eating behaviour and dietary patterns in children. Appetite 2012, 59, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messerli-Bürgy, N.; Stülb, K.; Kakebeeke, T.H.; Arhab, A.; Zysset, A.E.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Schmutz, E.A.; Meyer, A.H.; Ehlert, U.; Garcia-Burgos, D.; et al. Emotional eating is related with temperament but not with stress biomarkers in preschool children. Appetite 2018, 120, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheinbein, D.H.; Stein, R.I.; Hayes, J.F.; Brown, M.L.; Balantekin, K.N.; Conlon, R.P.K.; Saelens, B.E.; Perri, M.G.; Welch, R.R.; Schechtman, K.B.; et al. Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms among children seeking treatment for obesity: A social-ecological approach. Pediatr. Obes. 2019, 14, e12518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.T.; Huang, D.H.; Hsu, T.H.; Hong, F.Y. Children’s stress, negative emotions, emotional eating, and eating disorders: A moderated mediation model. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagleton, S.G.; Na, M.; Savage, J.S. Food insecurity is associated with higher food responsiveness in low-income children: The moderating role of parent stress and family functioning. Pediatr. Obes. 2022, 17, e12837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bell, E.M.; Ghassabian, A.; Polinski, K.J.; Robinson, S.L.; Sundaram, R.; Yeung, E. Associations of toddler mechanical/distress feeding problems with psychopathology symptoms five years later. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2022, 63, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan Güney, H.; Göbel, P. Assessment of mindfulness in addressing emotional eating and perceived stress among children aged 9–11 years. Nutr. Hosp. 2025, 42, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, J.; Semmler, C.; Carnell, S.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.; Wardle, J. Continuity and stability of eating behaviour traits in children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blissett, J.; Haycraft, E.; Farrow, C. Inducing preschool children’s emotional eating: Relations with parental feeding practices. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrist, A.W.; Hubbs-Tait, L.; Topham, G.L.; Shriver, L.H.; Page, M.C. Emotion regulation is related to children’s emotional and external eating. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2013, 34, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blissett, J.; Farrow, C.; Haycraft, E. Relationships between observations and parental reports of 3–5 year old children’s emotional eating using the Children’s Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. Appetite 2019, 141, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinsbekk, S.; Bjørklund, O.; Llewellyn, C.; Wichstrøm, L. Temperament as a predictor of eating behavior in middle childhood—A fixed effects approach. Appetite 2020, 150, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buja, A.; Manfredi, M.; Zampieri, C.; Minnicelli, A.; Bolda, R.; Brocadello, F.; Gatti, M.; Baldovin, T.; Baldo, V. Is emotional eating associated with behavioral traits and Mediterranean diet in children? A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Liu, X.; Guo, H.; Zhou, Q. The associations between caregivers’ emotional and instrumental feeding, children’s emotional eating, and children’s consumption of ultra-processed foods in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, M.; Obregón, A.M.; Weisstaub, G.; Burrows, R.; Patiño, A.; Ho-Urriola, J.; Santos, J.L. Association between feeding behavior, and genetic polymorphism of leptin and its receptor in obese Chilean children. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 31, 1044–1051. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, N.; Sioen, I.; Ruige, J.; De Henauw, S. Children’s psychosocial stress and emotional eating: A role for leptin? Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2017, 50, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herle, M.; Fildes, A.; Steinsbekk, S.; Rijsdijk, F.; Llewellyn, C.H. Emotional over- and under-eating in early childhood are learned not inherited. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herle, M.; Fildes, A.; Rijsdijk, F.; Steinsbekk, S.; Llewellyn, C. The Home Environment Shapes Emotional Eating. Child Dev. 2018, 899, 1423–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herle, M.; Fildes, A.; Llewellyn, C.H. Emotional eating is learned not inherited in children, regardless of obesity risk. Pediatr. Obes. 2018, 13, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohrt, T.K.; Perez, M.; Liew, J.; Hernández, J.C.; Yu, K.Y. The influence of temperament on stress-induced emotional eating in children. Obes. Sci. Pract. 2020, 6, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Type | Study Population | Children EE Assessment * | Basic Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional study | 75 USA children (40 boys and 35 girls) aged 3–6 years | Behavioral index of disinhibited eating | Familial effects on childhood overweight may be different based on parent and child gender (p < 0.05). Mothers’ dietary disinhibition may mediate familial similarities in degree of overweight for mothers and daughters (p < 0.05). | Cutting et al., 1999 [19] |

| Cross-sectional study | 368 Germany children (164 boys and 204 girls) aged 8–11 years (95.7% aged 10–11 years) | Not validated questionnaire | Unusual eating attitude was highly related to a harmful parent–child relationship regardless of childhood body weight (p < 0.001). | Schuetzmann et al., 2008 [20] |

| Cross-sectional study | 450 USA children aged 6–8 years (gender not reported) | DEBQ-C | Emotional eating was adversely predicted by reliable parental behavior (p < 0.036) and family open affection (p < 0.001) and emotional expression (p < 0.001) and directly predicted by parents’ reduced response to childhood harmful emotional behavior (p = 0.003). | Topham et al., 2011 [21] |

| Longitudinal study | 1327 Denmark children aged 5–7 years (full text and gender cannot be retrieved) | A composite instrument assessing eating behaviors and their impact | Picky consumption was related to psychopathology within diseases (p < 0.001). Emotional undereating was related to emotion and functional somatic symptomatology (p < 0.001). | Micali et al., 2011 [22] |

| Cross-sectional study | 106 USA children (45.3% boys and 54.7% girls) aged 8–12 years | CEBQ | Parent variables were more intensely correlated with childhood emotional eating, controlling for child age and sex (p < 0.001). Emotional eating attitude was the most significant parent factor related to children’s emotional eating (p < 0.001). | Braden et al., 2014 [23] |

| Cross-sectional study | 288 Belgium children (145 boys and 143 girls) aged 6–12 years | DEBQ-C | A borderline positive relationship was found between sweet food consumption incidence and “coercive control” (p = 0.014) and a marginal negative correlation between fruit and vegetable consumption incidence and “overprotection” was noted (p = 0.102 and p = 0.009, respectively). Children more commonly consumed soft drinks after their parents had decreased levels of “structure” and increased levels of “overprotection” (p = 0.123 and p = 0.031, respectively). | Philips et al., 2014 [24] |

| Cross-sectional study | 306 Australian children aged 2 years (gender not reported) | DEBQ-C | Mothers’ and children’s emotional eating was related to mother’s symptomatology of depression, anxiety, and stress (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively). | Rodgers et al., 2014 [25] |

| Cross-sectional study | 95 USA children (49 boys and 46 girls) aged 4.5–9 years | DEBQ-C | The relationship of parental and childhood emotional eating was mediated by feeding for emotional regulation when children’s self-regulation concerning eating was decreased (p = 0.001), but not when self-regulation in eating was increased (p = 0.105). | Tan et al., 2015 [26] |

| Longitudinal study | 35 UK children (16 boys and 19 girls) initially 4–5 years and finally aged 5–7 years | Not validated questionnaire | Parents excessively regulate children’s foodstuff consumption and seem to accidentally educate their child to highly consume palatable foods to manage harmful emotional behavior after a 2-year follow-up (p < 0.001). | Farrow et al., 2015 [27] |

| Cross-sectional study | 77 UK children (49.0% boys and 51.0% girls) aged 3–12 years | CEBQ | A considerable direct effect of maternal attachment anxiety on child emotional overeating was noted (p = 0.002). A substantial indirect impact of mothers’ anxiety attachment on children’s emotion over-eating through emotion feeding approaches (p = 0.02). A considerable indirect impact of mothers’ attachment anxiety on emotion eating approaches through children emotional overeating (p = 0.01). | Hardman et al., 2016 [28] |

| Cross-sectional study | 60 Germany children (27 boys and 33 girls) aged 18–55 months | CEBQ | An indirect impact of mentalization through emotional eating on mothers’ (p < 0.05) but not on children’s weight and through mother–child attachment on children’s weight (p = 0.45 and p = 0.42). | Keitel-Korndörfer et al., 2016 [29] |

| Longitudinal study | 229 UK children (120 boys and 129 girls) with a mean age of 8.73 years at borderline and a one year follow-up | EPIC | Perceptions of parents’ force to eat and limitations considerably diminished the relations among eating behaviors over a 12-month period (p < 0.001). | Houldcroft et al., 2016 [30] |

| Cross-sectional study | 254 USA children (31.7% boys and 68.3% girls) with a mean age of 4.17 years | CEBQ | The association of parents’ practice of food as a reward and children emotional overeating was partly mediated by children’s self-modulation in consumption after adjusting for parental and child sex, family salary, and race/ethnicity (p ≤ 0.001). | Powell et al., 2017 [31] |

| Cross-sectional study | 100 children (33.0% boys and 57.0% girls) aged 8 to 13 years from Switzerland | DEBQ-C | Parents’ critique and, to a lower extent, parents’ emotional overinvolvement were certainly correlated with child emotional intake, and this association was facilitated by children’s harmful pressure (p < 0.05). | Munsch et al., 2017 [32] |

| Longitudinal study | 997 Norwegian children (49.1% boys and 50.9% girls) aged 4 years old followed up at ages 6 (795 children), 8 (699 children), and 10 (702 children) years | CEBQ | The elevated amounts of emotion feeding were associated with increased amounts of emotional consumption and vice versa, after adjustment for BMI, and firstly, amounts of feeding and eating (p < 0.001). Elevated amounts of temperamental harmful affectivity (at the age of 4 years) enhanced the probability of developing emotional eating and feeding in the future (p < 0.001). | Steinsbekk et al., 2018 [33] |

| Longitudinal study | 3514 children (49.1% boys and 50.9% girls) aged 4 years with a follow-up at the age of 10 years from Netherlands | CEBQ | Three patterns of emotional overeating and 5 patterns of food responsiveness were recognized. Obesogenic eating attitude patterns were related to an increased childbirth body weight and BMI, emotional and behavioral problems, mothers’ overweight or obesity and monitoring feeding approaches (p < 0.001). | Derk et al., 2019 [34] |

| Longitudinal study | Norwegian children (49.8% boys and 50.2% girls) followed up at the age of 6 (797 children), 8 (699 children) and 10 (702 children) years | CEBQ | Low (temperamental) soothability and less parental structuring at age 6 were associated with elevated emotional overeating at the age of 10 years (p = 0.003) and that decreased family performance at the age of 6 years was associated with higher emotional undereating throughout the same interval (p = 0.014). | Bjørklund et al., 2019 [35] |

| Case–control study | 440 children (272 boys and 168 girls) aged 3–6 years from India | CEBQ | A positive association of food avoidance subscales of CEBQ along with certain food-approaching subscales with tooth decay conditions was noted (p < 0.01). Parents’ feeding behaviors like encouragement and instrumental feeding resulted in a reduction in children’s tooth decay conditions in comparison to control and emotion feeding (p < 0.01). | Nembhwani and Winnier, 2020 [36] |

| Cross-sectional study | 478 Australian children (48.2% boys and 51.8% girls) aged 5–10 years | CEBQ | Maternal emotional overeating and food responsiveness were each positively related to the parallel childhood eating behavior (p < 0.01). Both the relation between mothers and childhood emotion overeating and between mothers and childhood food responsiveness were partly facilitated using feeding as a reward and overt limitation (p < 0.01). | Miller et al., 2020 [37] |

| Cross-sectional study | 284 USA children (47.2% boys and 52.8% girls) aged 4–6 years | CEBQ | Parents reporting their parenting stress increased, and elevated parenting stress, which was related to more frequent stress to eat and lower frequency of controlling their children’s nutritional behavior (p = 0.01 and p = 0.03, respectively). | González et al., 2022 [38] |

| Cross-sectional study | 244 UK children (48.0% boys and 52.0% girls) aged 3–5-year | CEBQ | Children’s emotional eating was ascribed to interrelations among higher emotional eating by parents, the usage of food as a reward, constraint of food for health purposes and harmful affective temperaments (p ≤ 0.0001). | Stone et al., 2022a [39] |

| Cross-sectional study | 185 UK children (48.0% boys and 52.0% girls) aged 3–5 years | CEBQ | The relationship between maternal reports of maternal emotional eating and child emotional eating was mediated by maternal usage of food as a reward or of restraint for health reasons (p = 0.004 and p < 0.001, respectively). | Stone et al., 2022b [40] |

| A laboratory-based experimental study | 47 USA (50.0% boys and 50% girls) children aged 3–5 years | Not validated questionnaire | Mothers within both groups who reported elevated emotional eating functioned themselves (p = 0.014) and their children (p = 0.007) lower amounts of foods, and mothers ate lower food amounts (p = 0.045). | Warnick et al., 2022 [41] |

| Cross-sectional study | 2038 children (1001 boys and 1037 girls) aged 10–11 years from Taiwan | Emotional Eating items from the TFEQ-R18 scale | Mothers’ foreign nationality affected children emotional eating mainly by enhancing rewarding (p = 0.001) and pressure-to-eat strategies (p = 0.01) combined with decreased health literacy (p < 0.0001) that eventually lowered management strategies. | Chen et al., 2025 [42] |

| Study Type | Study Population | Children EE Assessment * | Basic Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional study | 292 obese children (40.0% boys and 60.0% girls) aged 9–11 years from Belgium | PCSC | Significant associations were noted between emotional eating and negative feelings of physical competency; between external eating and negative feelings of self-worth; and between both eating styles and diverse dimensions of problematic behaviors (p < 0.001 for all). | Braet et al., 1997 [43] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1213 black girls and 1166 white girls at the age of 9 to 10 years from USA | EIES | Black girls had considerably elevated emotion-induced eating scores compared to white girls (p < 0.001). In all races, a negative relationship was noted among BMI and emotion-induced eating (p < 0.001). | Striegel-Moore et al., 1999 [44] |

| Cross-sectional study | 240 Portuguese children (117 boys and 123 girls) aged 3–13 years (mean age 7.9 years) | CEBQ | All CEBQ sub-scales were substantially associated with BMI z-scores (p < 0.001). Food approach scales were also positively associated with BMI z-scores and food avoidance negatively related (p < 0.001). | Viana et al., 2008 [45] |

| Cross-sectional study | 135 children (68 boys and 67 girls) aged 6–7 years from Netherlands | CEBQ | BMI z-scores were directly related to the ‘foods approaches’ subscales of the CEBQ (p = 0.016, and p = 0.027) and negatively with ‘foods’ avoidant’ subscales (p = 0.006). | Sleddens et al., 2008 [46] |

| Cross-sectional study | 406 UK children aged 7–9 years (239 children, 51.0% boys and 49.0% girls) and 9–12 years old (167 children, 39.5 boys and 60.5% girls) | CEBQ | Satiety responsiveness/slowness in eating and food fussiness indicated an ordered negative relation to body weight (p < 0.0001, and p = 0.023, respectively). Food responsiveness, enjoyment of foods, emotional overeating and desire to drink were positively interrelated (p < 0.001). | Webber et al., 2009 [47] |

| Longitudinal study | UK children (boys:girls ratio = 1:1), time points: 6 weeks (811 children), 12 months (620 children), 5–6 years (506 children), 6–8 years (583 children) | CEBQ | Children with elevated emotional overeating and desire to drink presented increased BMIs, while children with higher levels of satiety responsiveness exhibited lower BMIs (p < 0.005). | Parkinson et al., 2010 [48] |

| Cross-sectional study | 241 UK children (55.0% boys and 45.0% girls) aged 3–8 years (mean age: 5 years) | CEBQ | Children with more emotional temperaments showed more food- avoidant eating behaviors (p < 0.001). Elevated child BMI was related to additional food approach eating behaviors; however, BMI was not associated with child temperament (p < 0.001). | Haycraft et al., 2011 [49] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1730 Canadian children (884 boys and 846 girls) aged 4–5 years | CEBQ | Substantial differentiations were noted between body weight status groups concerning food responsiveness, emotional overeating, enjoyment of foods, satiety responsiveness, slowness in eating, and food fussiness (p < 0.01 for all). | Spence et al., 2011 [50] |

| Cross-sectional study | 4987 children (50.1% boys and 49.9% girls) aged 4 years from Netherlands | CEBQ | Elevated children’s food responsiveness, enjoyment of foods and parents’ constraints were related to a greater BMI (p < 0.001 for all). Emotional undereating, satiety responsiveness and fussiness of children as well as parents’ pressure to eat were inversely associated with child BMI (p < 0.001 for all). | Jansen et al., 2012 [51] |

| Cross-sectional study | 3137 children (50.3% boys, 49.7% girls) aged 3 to 4 years from Netherlands | CEBQ | Children having enhanced levels of emotional difficulties exhibited decreased BMI-SDS after adjusting for relevant covariates for parent reports of emotional problems (p < 0.001). | Mackenbach et al., 2012 [52] |

| Longitudinal study | USA children aged 2 years with a one-year follow-up (323 children at baseline and 222 children one year later; gender not reported) | CEBQ | Mothers’ feeding methods exerted a crucial impact in the development of body weight increase and obesogenic eating behavior in children (p = 0.005, and p = 0.021, respectively) | Rodgers et al., 2013 [53] |

| Longitudinal study | 521 children (255 boys and 266 girls) from Germany with a mean age of 8.26 years | EPIC | Substantial relationships of eating patterns with BMI were noted. Overweight children consciously restrain their eating (p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001, respectively). | Hirsch et al., 2014 [54] |

| Cross-sectional study | 335 (48.7% boys and 51.3% girls) Brazilian children aged 6–10 years (mean age: 87.9 months) | CEBQ | Children presenting excessive body weight exhibited elevated scores at the CEBQ subscales related to “food approach”(p < 0.001) and elevated scores on two “food avoidance” subscales (p < 0.001, and p = 0.003) compared to normal-weight children. | dos Passos et al., 2015 [55] |

| Longitudinal study | 995 Norwegian children aged 4 years, 760 children aged 6 years old, and 687 children aged 8 years (gender proportion not reported) | CEBQ | Children whose eating was remarkably induced by the sight and smell of foods prospectively showed elevated body weight increase (p < 0.001). Excessive body weight also predicted increased food approach behavior (p < 0.001). | Steinsbekk et al., 2015 [56] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1058 Chilean children (49.2% boys and 50.8% girls) aged 7–10 years | CEBQ | A considerable association of eating behavior levels with BMI z-scores in children was noted (p < 0.0001). Children BMI was directly related to pro-intake eating behavior levels and inversely related to anti-intake eating behavior levels (p < 0.0001 for both). | Sánchez et al., 2016 [57] |

| Cross-sectional study | 5426 children (46.0% boys and 54.0% girls) aged 9–11 years from 12 countries | EIES | Emotional eating was positively and consistently (across 12 study sites) related to a non-healthy dietary pattern (p < 0.0001). Emotional eating was not correlated with BMI (p = 0.493). | Jalo et al., 2019 [58] |

| Validity study | 147 USA overweight or obese children (34.0% boys and 66.0% girls) aged 8–12 years (mean age: 10.4 years) | EES-C | The initial interpretative importance of the EES-C between treatment-seeking children affected by overweight or obesity should be assigned on a single general concept, and not on the 3 or 5 subconstructs (p < 0.05). | Kang Sim et al., 2019 [59] |

| Cross-sectional study | 400 children aged 11–13 years from India (gender was not reported) | EES-C | EES levels were shown to be considerably elevated amongst caries-free subjects compared with those who exhibited mean “decayed and filled teeth”/“decayed missing and filled teeth (dft/DMFT)” score > 0 (p = 0.015, p = 0.001, and p = 0.076). | Goel et al., 2022 [60] |

| Study Type | Study Population | Children EE Assessment * | Basic Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional study | 356 Latino (42.6%), African (21.6%) and Asian (19.2%) American children (43.0% boys and 57.0% girls) aged 8–12 years | DEBQ-C | There were considerable relationships between sleep onset latency and emotional eating (p = 0.030), depressive symptomology (p < 0.0001) and trait anxiety (p < 0.0001). | Nguyen-Rodriguez et al., 2010 [61] |

| Cross-sectional study | 437 Belgium children (49.9% boys and 50.1% girls) aged 5–12 years (median age about 9.0 years) | DEBQ-C | Stressful events, negative emotions and problems were directly related to emotional eating and an unhealthier dietary pattern (p < 0.01). | Michels et al., 2012 [62] |

| Cross-sectional study | 476 Swiss children (251 boys and 225 girls) aged 2–6 years (mean age: 3.89 years) | CEBQ | Children presenting difficulties in their temperament may have increased risk of emotional eating and body weight modulation troubles in later childhood (p < 0.001 for all). | Messerli-Bürgy et al., 2018 [63] |

| Cross-sectional study | 241 overweight or obese children (90 boys and 151 girls) aged 7–11 years from USA | CBC | Child eating disorder pathology, parents’ use of psychological control, and reduced children personal social condition were substantially related to increased children’s depressive symptoms (p < 0.001 for all). Children eating disorders’ pathology and parents’ psychological management were significantly related to elevated child anxiety symptomatology (p < 0.001 for all). | Sheinbein et al., 2019 [64] |

| Cross-sectional study | 1120 children (57.5% boys and 42.5% girls) aged 11–12 years from Taiwan | DEBQ-C | Those children who self-reported elevated anxiety and depressive levels exhibited increased stress events and emotional eating compared with those with reduced anxiety and depressive levels (p < 0.001, and p < 0.01, respectively). | Wu et al., 2020 [65] |

| Cross-sectional study | 361 children (6.0% boys and 94.0% girls) aged 3–5 years from USA | CEBQ | Child food insecurity was only related to greater food responsiveness amongst children of parents stating elevated scores of perceived stress and decreased scores of family functionality (p = 0.04, and p = 0.01, respectively). | Eagleton et al., 2022 [66] |

| Longitudinal study | 1136 children (53.3% boys and 46.7% girls) aged 2.5 years from USA with a follow-up at 8 years | DEBQ-C | Mechanical/distress feeding difficulties in children aged 2.5 years. No food refusal difficulties were related to ADHD, problematic behavior (OD/CD), and anxiety/depressive symptomatology at the age of eight years (p = 0.012, and p = 0.002, respectively). | Putnick et al., 2022 [67] |

| Cross-sectional study | 349 Turkish children (128 boys and 221 girls) aged 9–11 years | EES-C | A positive, weak relationship was also observed between children’ age and emotional eating, anxiety–anger–disappointment subscales and perceived stress scores (p = 0.003, p = 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively) | Doğan Güney et al., 2024 [68] |

| Study Type | Study Population | Children EE Assessment * | Basic Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal study | 400 USA twin children (44.3% boys and 55.5% girls) aged 4 years at the baseline and 322 children (38.5% boys and 61.5% girls) with a follow up at the age of 10 years | CEBQ | Satiety responsiveness, eating slowness, food fussiness, and emotional undereating were reduced, while food responsiveness, food enjoyment and emotional overeating were enhanced (p < 0.0001 for all). | Ashcroft et al., 2008 [69] |

| Case–control study | 25 UK children (7 boys and 5 girls in the experimental group, 6 boys and 7 girls in the control group) aged 3–5 years | CFPQ | Children of mothers using foods for emotional modulation more often consumed sweet palatable foods in the absence of hunger than children of mothers using this feeding method rarely (p = 0.0008). | Blissett et al., 2010 [70] |

| Longitudinal study | 782 second graders (50.7% boys and 49.3% girls) were followed up through third grade from USA | DEBQ-C | Children’s emotional modulation was substantially associated with both external and emotional eating within grades (p < 0.0001). Reactivity was more consistently associated with eating regulation than was inhibition (p < 0.0001). | Harrist et al., 2013 [71] |

| Case–control study | 62 UK children (33 boys and 29 girls) aged 34–59 months (mean age 46.0 months) | CEBQ | Children presenting elevated levels of emotional undereating on the CEBQ consume less energy from crisps/potato chips and cookies (p < 0.05) throughout a negative mood state, but not during a neutral mood. | Blissett et al., 2019 [72] |

| Longitudinal study | Norwegian children followed up from age 4 (997 children) to age 6 (795 children), 8 (699 children) and 10 (702 children) years (gender not reported) | CEBQ | Temperament was implicated in the etiology of children’s eating patterns. Harmful affectivity influenced both ‘foods approach’ and ‘foods avoidant’ behavior (p < 0.001 for both) | Steinsbekk et al., 2020 [73] |

| Cross-sectional study | 178 Italian children (54.5% boys and 45.5% girls) aged 8–9 years | CEBQ | Emotional overeating was positively related to both emotional symptoms and hyperactivity and inversely associated with peer problems (p < 0.01, p < 0.01, and p = 0.03, respectively). Emotional undereating was also directly related to the number of siblings and inversely correlated with high Mediterranean diet compliance (p = 0.04, and p = 0.02, respectively). | Buja et al., 2022 [74] |

| Cross-sectional study | 408 Chinese children (52.2% boys and 47.8% girls) aged 6–36 months (mean age: 22.4 months) | CEBQ | Caregivers’ emotional and instrumental feeding was directly related to children’s intake of ultra-processed foods, a higher frequency of ultra-processed food consumption weekly, and a larger amount of ultra-processed food consumption weekly (p < 0.01 for all). Children’s elevated incidence of emotional undereating was related to their ultra-processed food consumption and a higher frequency of ultra-processed food consumption weekly (p < 0.01 for all). | An et al., 2022 [75] |

| Study Type | Study Population | Children EE Assessment * | Basic Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional study | 221 Chilean obese children with a mean age of 9.7 years (gender not reported) | CEBQ | The dimensions “slow eating”, “emotional eating”, “foods enjoyment” and “uncontrolling eating” were considerably related to some polymorphisms of leptin and leptin receptor (p < 0.01 for all). | Valladeres et al., 2014 [76] |

| Longitudinal study | Belgium Children (48.7% boys and 51.3% girls) were between 5 and 10 years old at baseline (308 children) and between 7 and 12 years old at follow-up (174 children) | DEBQ-C | Stress marker (overall cortisol output) was substantially related to elevated leptin concentrations, but only in girls and cross-sectionally (p = 0.029). Leptin was not identified as a considerable predictor of non-healthy food intake (p > 0.05). | Michels et al., 2017 [77] |

| Longitudinal study | 2054 UK twin children aged 2 years which were followed up to 5 years (boys:girls ratio about 1:1) | CEBQ | Emotional overeating and emotional undereating were positively interrelated, and this relationship was clarified by common shared environmental influences (p < 0.001). | Herle et al., 2017 [78] |

| Longitudinal study | 2402 UK twin children aged 2 years which were followed up to 5 years (boys:girls ratio about 1:1) | CEBQ | Genetic influences on emotional overeating were minimal compared to shared environmental influences (p < 0.001). | Herle et al., 2018a [79] |

| Longitudinal study | 394 UK twin children aged 4 years (44.9% boys and 55.1% girls) | CEBQ | Genetic impact was not considerable, whereas shared environmental circumstances were implicated in the 71% variance in emotional overeating and 77% in emotional undereating (p < 0.01). | Herle al., 2018b [80] |

| Cross-sectional study | 147 children (49.7% boys and 50.3% girls) aged 4–6 years from USA | SEE | The interconnection of 5-HTTLPR with impulsivity and negative affectivity considerably predicted body fat percentage. The interconnection of 5-HTTLPR with impulsivity and negative affectivity considerably predicted both total calorie intake and rate of overall calorie intake (p < 0.01). | Ohrt et al., 2020 [81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mentzelou, M.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Psara, E.; Alexatou, O.; Koimtsidis, T.; Giaginis, C. Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating in Children: A Narrative Review. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030066

Mentzelou M, Papadopoulou SK, Psara E, Alexatou O, Koimtsidis T, Giaginis C. Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating in Children: A Narrative Review. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(3):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030066

Chicago/Turabian StyleMentzelou, Maria, Sousana K. Papadopoulou, Evmorfia Psara, Olga Alexatou, Theodosis Koimtsidis, and Constantinos Giaginis. 2025. "Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating in Children: A Narrative Review" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 3: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030066

APA StyleMentzelou, M., Papadopoulou, S. K., Psara, E., Alexatou, O., Koimtsidis, T., & Giaginis, C. (2025). Exploring the Impact of Emotional Eating in Children: A Narrative Review. Pediatric Reports, 17(3), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17030066