Adolescent-Reported Interparental Conflict and Related Emotional–Behavioral Difficulties: The Mediating Role of Psychological Inflexibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Ethical Statement

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

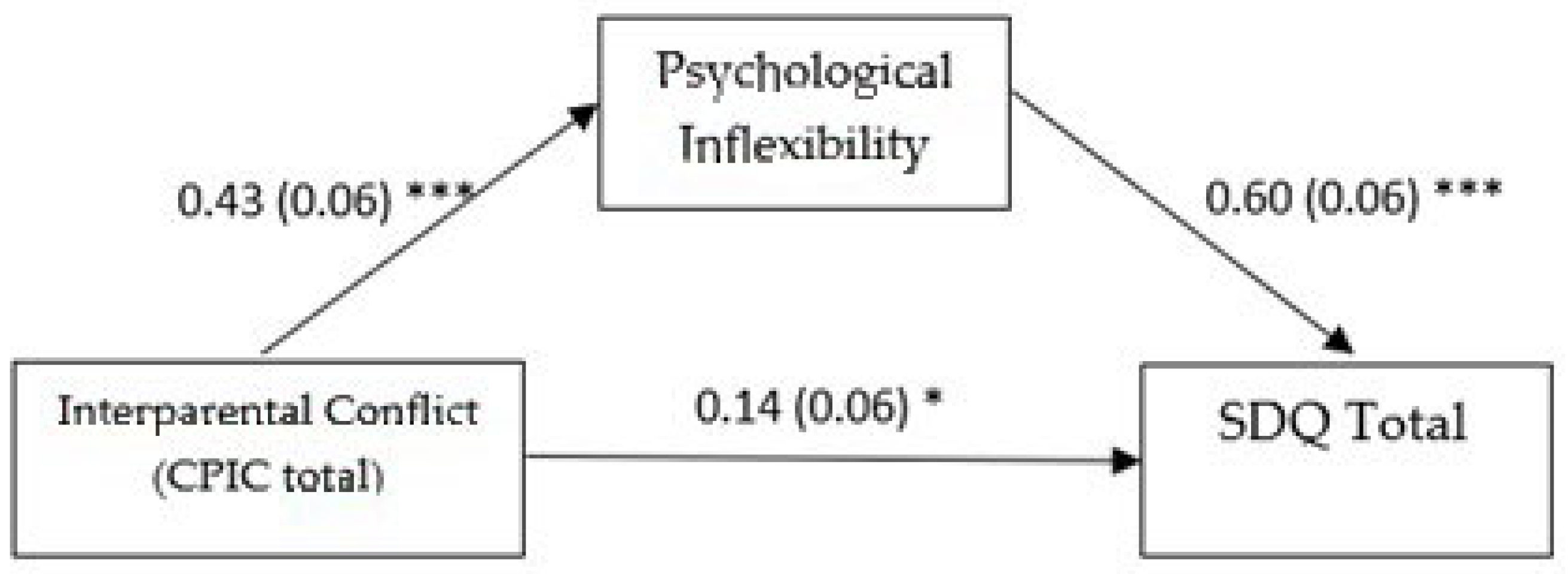

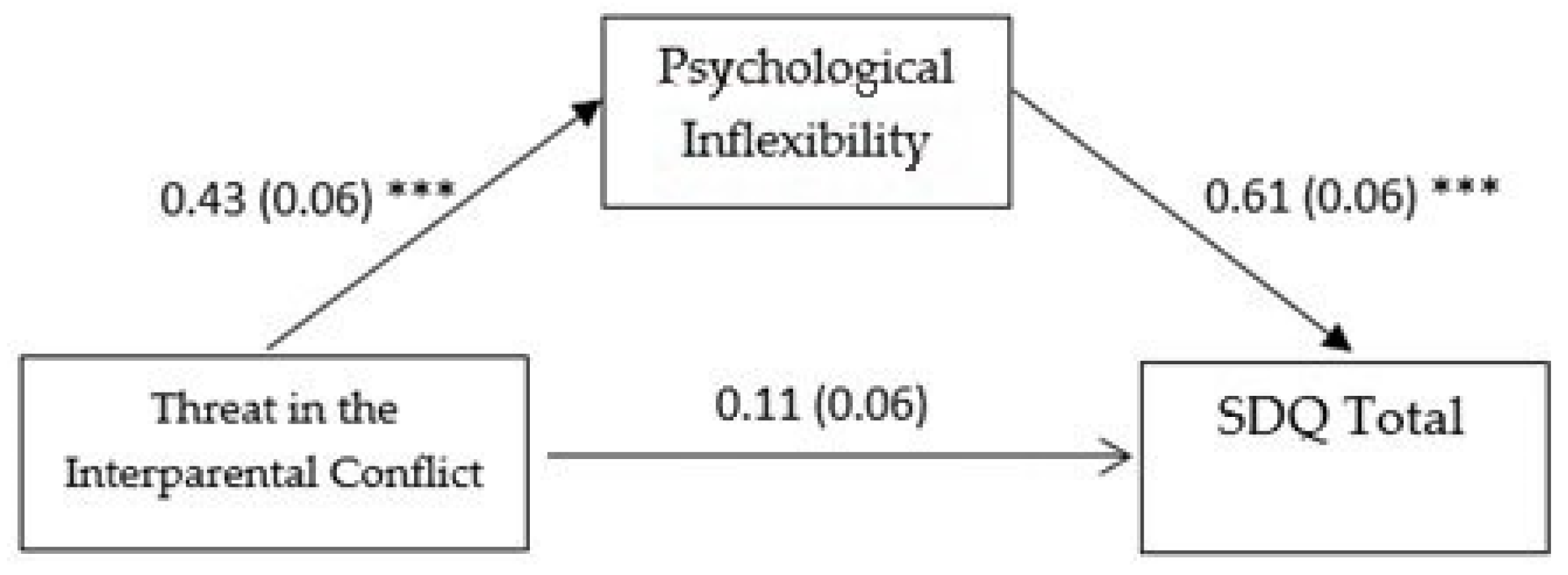

3.2. Main Explanatory Indirect Effect Analyses: Mediation Models

4. Discussion

Limits and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brock, R.L.; Kochanska, G. Interparental conflict, children’s security with parents, and long-term risk of internalizing problems: A longitudinal study from ages 2 to 10. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouriles, E.N.; Rosenfield, D.; McDonald, R.; Mueller, V. Child Involvement in Interparental Conflict and Child Adjustment Problems: A Longitudinal Study of Violent Families. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2014, 42, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, K.H.; Harold, G.T. Interparental conflict, negative parenting, and children’s adjustment: Bridging links between parents’ depression and children’s psychological distress. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eldik, W.M.; de Haan, A.D.; Parry, L.Q.; Davies, P.T.; Luijk, M.P.C.M.; Arends, L.R.; Prinzie, P. The interparental relationship: Meta-analytic associations with children’s maladjustment and responses to interparental conflict. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 553–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warmuth, K.A.; Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Constructive and destructive interparental conflict, problematic parenting practices, and children’s symptoms of psychopathology. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, M.B.H.; Jorm, A.F. Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalizing problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 175, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Coplan, R.J.; Teng, Z.; Liang, L.; Chen, X.; Bian, Y. How does interparental conflict affect adolescent preference-for-solitude? Depressive symptoms as mediator at between- and within-person levels. J. Fam. Psychol. 2023, 37, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camisasca, E.; Miragoli, S.; Di Blasio, P. Children’s Triangulation during Inter-Parental Conflict: Which Role for Maternal and Paternal Parenting Stress? J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 1623–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, G.T.; Sellers, R. Annual Research Review: Interparental conflict and youth psychopathology: An evidence review and practice focused update. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2018, 59, 374–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, C.; Anthony, C.; Krishnakumar, A.; Stone, G.; Gerard, J.; Pemberton, S. Interparental Conflict and Youth Problem Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. J. Child Fam. Stud. 1997, 6, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, G.; Niu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Wu, J. The Association between Interparental Conflict and Youth Anxiety: A Three-level Meta-analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 2021, 50, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, K.A. Children’s Responses to Interparental Conflict: A Meta-Analysis of Their Associations with Child Adjustment. Child Dev. 2008, 79, 1942–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, R.; van der Valk, I.E.; Deković, M.; Branje, S. A meta-analysis on interparental conflict, parenting, and child adjustment in divorced families: Examining mediation using meta-analytic structural equation models. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 79, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Lindsay, L.L. Interparental Conflict and Adolescent Adjustment: Why Does Gender Moderate Early Adolescent Vulnerability? J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E.M.; Davies, P.T. Marital Conflict and Children: An Emotional Security Perspective; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji, O.A.; Idemudia, E.S. The multidimensionality of inter-parental conflict on aggression and mental health among adolescents. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, M. The Resolution of Conflict: Constructive and Destructive Processes. Am. Behav. Sci. 1973, 17, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.H.; Fincham, F.D. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 108, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leve, L.D.; Cicchetti, D. Longitudinal transactional models of development and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28, 621–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.T.; Cummings, E.M. Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 116, 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engfer, A. The interrelatedness of marriage and the mother-child relationship. Relatsh. Within Fam. Mutual Influ. 1988, 7, 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Erel, O.; Burman, B. Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 118, 108–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forresi, B.; Giani, L.; Scaini, S.; Nicolais, G.; Caputi, M. The Mediation of Care and Overprotection between Parent-Adolescent Conflicts and Adolescents’ Psychological Difficulties during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Which Role for Fathers? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, G.T.; Elam, K.K.; Lewis, G.; Rice, F.; Thapar, A. Interparental conflict, parent psychopathology, hostile parenting, and child antisocial behavior: Examining the role of maternal versus paternal influences using a novel genetically sensitive research design. Dev. Psychopathol. 2012, 24, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grych, J.H.; Seid, M.; Fincham, F.D. Assessing Marital Conflict from the Child’s Perspective: The Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Dev. 1992, 63, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.H.; Harold, G.T.; Miles, C.J. A Prospective Investigation of Appraisals as Mediators of the Link Between Interparental Conflict and Child Adjustment. Child Dev. 2003, 74, 1176–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, E.M.; George, M.R.W.; McCoy, K.P.; Davies, P.T. Interparental Conflict in Kindergarten and Adolescent Adjustment: Prospective Investigation of Emotional Security as an Explanatory Mechanism. Child Dev. 2012, 83, 1703–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K.L.; Wolchik, S.A.; Sandler, I.N.; West, S.G.; Reis, H.T.; Collins, L.M.; Lyon, A.R.; Cummings, E.M. Preventing mental health problems in children after high conflict parental separation/divorce study: An optimization randomized controlled trial protocol. Ment. Health Prev. 2023, 32, 200301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G.; Maffei, C. ACT: Teoria e Pratica Dell’Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; R. Cortina: Milano, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, S.C.; Luoma, J.B.; Bond, F.W.; Masuda, A.; Lillis, J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M.E.; MacLane, C.; Daflos, S.; Seeley, J.R.; Hayes, S.C.; Biglan, A.; Pistorello, J. Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, F.W.; Hayes, S.C.; Baer, R.A.; Carpenter, K.M.; Guenole, N.; Orcutt, H.K.; Waltz, T.; Zettle, R.D. Preliminary Psychometric Properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A Revised Measure of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Avoidance. Behav. Ther. 2011, 42, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Villatte, M.; Levin, M.; Hildebrandt, M. Open, Aware, and Active: Contextual Approaches as an Emerging Trend in the Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 7, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gloster, A.T.; Meyer, A.H.; Lieb, R. Psychological flexibility as a malleable public health target: Evidence from a representative sample. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2017, 6, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rottenberg, J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 30, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Ray-Sannerud, B.; Heron, E.A. Psychological flexibility as a dimension of resilience for posttraumatic stress, depression, and risk for suicidal ideation among Air Force personnel. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2015, 4, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Xie, J.; Owusua, T.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Qin, C.; He, Q. Is psychological flexibility a mediator between perceived stress and general anxiety or depression among suspected patients of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19)? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2021, 183, 111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroska, E.B.; Roche, A.I.; Adamowicz, J.L.; Stegall, M.S. Psychological flexibility in the context of COVID-19 adversity: Associations with distress. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 18, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taşören, A.B. Childhood maltreatment and emotional distress: The role of beliefs about emotion and psychological inflexibility. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 13276–13287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroska, E.B.; Roche, A.I.; O’hara, M.W. Childhood Trauma and Somatization: Identifying Mechanisms for Targeted Intervention. Mindfulness 2018, 9, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Hu, N.; Yu, H.; Xiao, H.; Luo, J. Parenting Style and Adolescent Mental Health: The Chain Mediating Effects of Self-Esteem and Psychological Inflexibility. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 738170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q. Adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptoms among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Mediating roles of poor sleep quality and psychological inflexibility. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-Sierra, P.; Manrique-G, A.; Hidalgo-Andrade, P.; Ruisoto, P. Psychological Inflexibility and Loneliness Mediate the Impact of Stress on Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in Healthcare Students and Early-Career Professionals During COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 729171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.K.; Pickett, S.M.; Orcutt, H.K. Experiential Avoidance as a Mediator in the Relationship Between Childhood Psychological Abuse and Current Mental Health Symptoms in College Students. J. Emot. Abus. 2006, 6, 67–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makriyianis, H.M.; Adams, E.A.; Lozano, L.L.; Mooney, T.A.; Morton, C.; Liss, M. Psychological inflexibility mediates the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and mental health outcomes. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2019, 14, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.H.; Cardoza-Fernandes, S. Understanding the impact of interparental conflict on children: The role of social cognitive processes. In Interparental Conflict and Child Development: Theory, Research, and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 157–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ubinger, M.E.; Handal, P.J.; Massura, C.E. Adolescent adjustment: The hazards of conflict avoidance and the benefits of conflict resolution. Psychology 2013, 4, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, J.H.; Fincham, F.D.; Jouriles, E.N.; McDonald, R. Interparental conflict and child adjustment: Testing the mediational role of appraisals in the cognitive-contextual framework. Child Dev. 2000, 71, 1648–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.N.; Hoerger, M. Parental child-rearing strategies influence self-regulation, socio-emotional adjustment, and psychopathology in early adulthood: Evidence from a retrospective cohort study. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faustino, B.; Vasco, A.B. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Cognitive Fusion on the Regulation of Psychological Needs. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2020, 50, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A.S.; Silk, J.S.; Steinberg, L.; Myers, S.S.; Robinson, L.R. The Role of the Family Context in the Development of Emotion Regulation. Soc. Dev. 2007, 16, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudarzi, T.; Cervin, M. Emotion dysregulation and psychological inflexibility in adolescents: Discriminant validity and associations with internalizing symptoms and functional impairment. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2024, 34, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R.D.; Conger, K.J. Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. J. Marriage Fam. 2002, 64, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Wilson, K.G.; Gifford, E.V.; Follette, V.M.; Strosahl, K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 64, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kul, A.; Türk, F. Is Psychological Inflexibility a Predictor of Depression and Anxiety of Pre-Adolescents? Int. J. Psychol. Educ. Stud. 2024, 11, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Fernández, G.; Rodríguez-Valverde, M.; Reyes-Martín, S.; Hernández-Lopez, M. The Role of Psychological Inflexibility and Experiential Approach on Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: An Exploratory Study. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, B. Adolescent Capacity to Consent to Participate in Research: A Review and Analysis Informed by Law, Human Rights, Ethics, and Developmental Science. Laws 2022, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringhenti, F. Contributo alla validazione di una misura di conflittualità genitoriale: La Children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC). Giunti Organ. Spec. 2005, 247, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fosco, G.M.; Grych, J.H. Emotional, cognitive, and family systems mediators of children’s adjustment to interparental conflict. J. Fam. Psychol. 2008, 22, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.; Meltzer, H.; Bailey, V. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A pilot study on the validity of the self-report version. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1998, 7, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essau, C.A.; Olaya, B.; Anastassiou-Hadjicharalambous, X.; Pauli, G.; Gilvarry, C.; Bray, D.; O’Callaghan, J.; Ollendick, T.H. Psychometric properties of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire from five European countries. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2012, 21, 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.A.; Lambert, W.; Baer, R.A. Psychological inflexibility in childhood and adolescence: Development and evaluation of the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth. Psychol. Assess. 2008, 20, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergus, T.A.; Valentiner, D.P.; Gillen, M.J.; Hiraoka, R.; Twohig, M.P.; Abramowitz, J.S.; McGrath, P.B. Assessing psychological inflexibility: The psychometric properties of the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth in two adult samples. Psychol. Assess. 2012, 24, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, J.; Hancock, K.; Hainsworth, C.; Bowman, J. Mechanisms of change: Exploratory outcomes from a randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for anxious adolescents. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2015, 4, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, M.; Ristallo, A.; Oppo, A.; Pergolizzi, F.; Presti, G.; Moderato, P. Ragazzi in lotta con emozioni e pensieri: La validazione della versione italiana dell’Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth (I-AFQ-Y). Psicoter. Cogn. E Comport. 2017, 23, 141–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Giani, L.; Crepaldi, C.; Morello, L.; Grazioli, S.; Scaini, S.; Caputi, M.; Michelini, G.; Forresi, B. L’inflessibilità psicologica nella relazione tra conflitto inter-parentale e difficoltà emotivo-comportamentali negli adolescenti: Uno studio di mediazione. Psicoter. Cogn. E Comport. 2025, 31, 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, E.M.; Davies, P.T.; Simpson, K.S. Marital conflict, gender, and children’s appraisals and coping efficacy as mediators of child adjustment. J. Fam. Psychol. 1994, 82, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, C.M.; Jost, S.A. Psychological flexibility as a mediator of the association between early life trauma and psychological symptoms. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 141, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C.; Strosahl, K.D.; Wilson, K.G. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Compas, B.E.; Jaser, S.S.; Dunbar, J.P.; Watson, K.H.; Bettis, A.H.; Gruhn, M.A.; Williams, E.K. Coping and emotion regulation from childhood to early adulthood: Points of convergence and divergence. Aust. J. Psychol. 2014, 66, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakšić, N.; Brajković, L.; Ivezić, E.; Topić, R.; Jakovljević, M. The role of personality traits in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Psychiatr. Danub. 2012, 24, 256–266. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.; Thompson, A. The development and maintenance of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in civilian adult survivors of war trauma and torture: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanninen, K.; Punamäki, R.; Qouta, S. The relation of appraisal, coping efforts, and acuteness of trauma to PTS symptoms among former political prisoners. J. Trauma. Stress 2002, 15, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, M.; Gil, S. Trauma as an objective or subjective experience: The association between types of traumatic events, personality traits, subjective experience of the event, and posttraumatic symptoms. J. Loss Trauma 2016, 21, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohrenwend, B.S.; Dohrenwend, B.P. Stressful Life Events: Their Nature and Effects; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wyler, A.R.; Masuda, M.; Holmes, T.H. Magnitude of Life Events and Seriousness of Illness. Psychosom. Med. 1971, 33, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Başoğlu, M.; Mineka, S.; Paker, M.; Aker, T.; Livanou, M.; Gök, Ş. Psychological preparedness for trauma as a protective factor in survivors of torture. Psychol. Med. 1997, 27, 1421–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C.R.; Andrews, B.; Rose, S. Fear, helplessness, and horror in posttraumatic stress disorder: Investigating DSM-IV Criterion A2 in victims of violent crime. J. Trauma. Stress 2000, 13, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, M.; McFarlane, A.C.; Burgess, P. Psychopathology following trauma: The role of subjective experience. J. Affect. Disord. 2005, 86, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerig, P.K. Moderators and Mediators of the Effects of Interparental Conflict on Children’s Adjustment. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 1998, 26, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, S.; Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Huang, A.; Liu, S. Interparental Conflict and Early Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: Parent-Child Triangulation as the Mediator and Grandparent Support as the Moderator. J. Youth Adolesc. 2024, 53, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, L.; Zhou, H.; Yu, S.; Chen, C.; Jia, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, C. Parent–child communication and self-esteem mediate the relationship between interparental conflict and children’s depressive symptoms. Child Care Health Dev. 2018, 44, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav. Ther. 2004, 35, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, A.; Agnew-Blais, J.; Danese, A.; Fisher, H.L.; Jaffee, S.R.; Matthews, T.; Polanczyk, G.V.; Arseneault, L. Associations between abuse/neglect and ADHD from childhood to young adulthood: A prospective nationally-representative twin study. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 81, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, F.; Vozzo, F.; Arcuri, D.; Maressa, R.; La Cava, E.; Malvaso, A.; Lau, C.; Chiesi, F. The longitudinal association between Perceived Stress, PTSD Symptoms, and Post-Traumatic Growth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The role of coping strategies and psychological inflexibility. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 13871–13886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wersebe, H.; Lieb, R.; Meyer, A.H.; Hofer, P.; Gloster, A.T. The link between stress, well-being, and psychological flexibility during an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy self-help intervention. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2018, 18, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CPIC Perceived threat | 0.66 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.42 *** | −0.05 |

| 2. CPIC Tot | - | 0.41 *** | 0.42 *** | −0.01 |

| 3. SDQ Tot | - | 0.69 *** | 0.02 | |

| 4. I-AFQ-Y Tot | - | −0.08 | ||

| 5. Age | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giani, L.; Amico, C.; Crepaldi, C.; Caputi, M.; Scaini, S.; Michelini, G.; Forresi, B. Adolescent-Reported Interparental Conflict and Related Emotional–Behavioral Difficulties: The Mediating Role of Psychological Inflexibility. Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020033

Giani L, Amico C, Crepaldi C, Caputi M, Scaini S, Michelini G, Forresi B. Adolescent-Reported Interparental Conflict and Related Emotional–Behavioral Difficulties: The Mediating Role of Psychological Inflexibility. Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(2):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020033

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiani, Ludovica, Cecilia Amico, Chiara Crepaldi, Marcella Caputi, Simona Scaini, Giovanni Michelini, and Barbara Forresi. 2025. "Adolescent-Reported Interparental Conflict and Related Emotional–Behavioral Difficulties: The Mediating Role of Psychological Inflexibility" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 2: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020033

APA StyleGiani, L., Amico, C., Crepaldi, C., Caputi, M., Scaini, S., Michelini, G., & Forresi, B. (2025). Adolescent-Reported Interparental Conflict and Related Emotional–Behavioral Difficulties: The Mediating Role of Psychological Inflexibility. Pediatric Reports, 17(2), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17020033