Look at My Body: It Tells of Suffering—Understanding Psychiatric Pathology in Patients Who Suffer from Headaches, Restrictive Eating Disorders, or Non-Suicidal Self-Injuries (NSSIs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

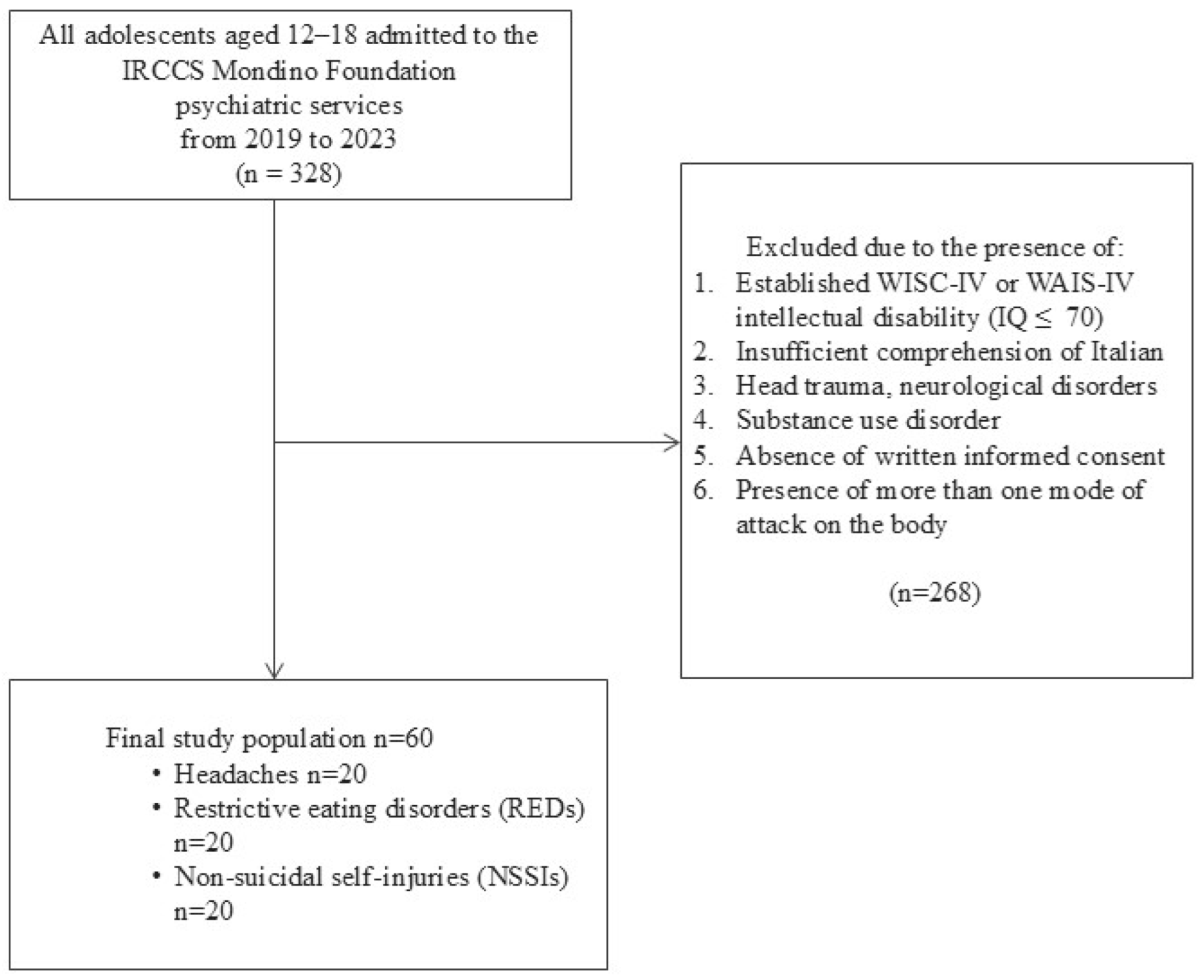

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

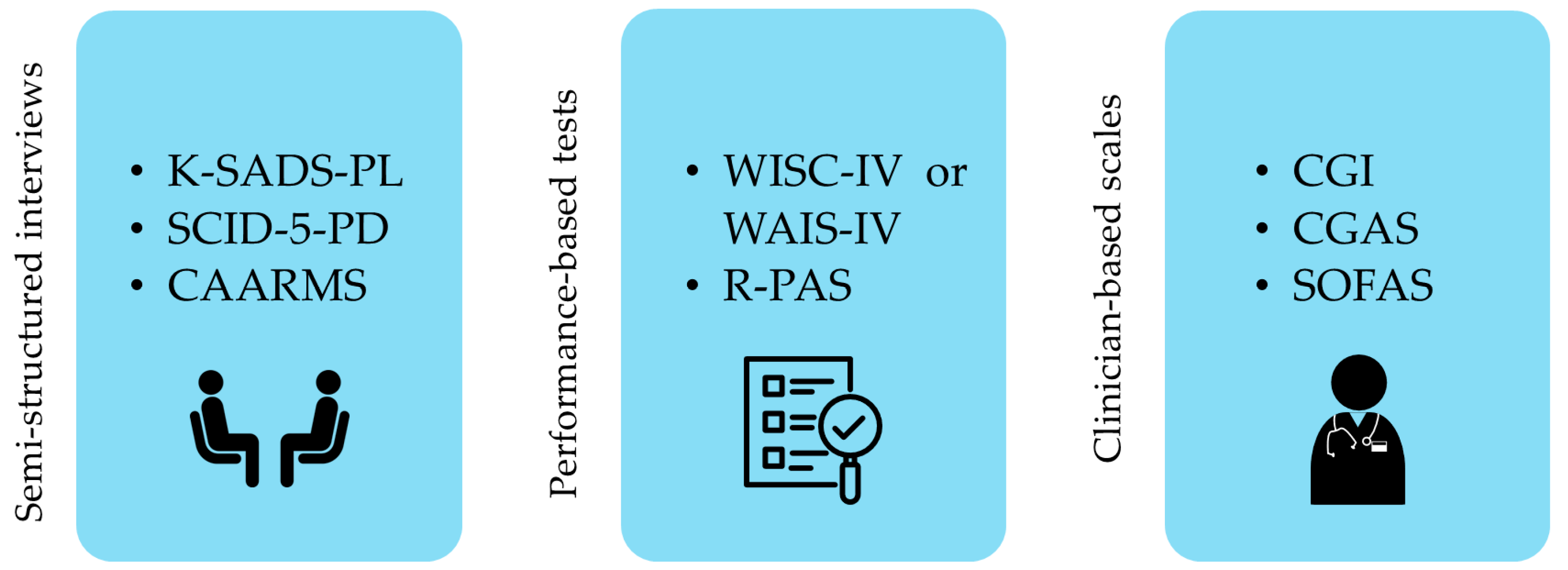

2.3. Procedures and Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blakemore, S.-J. Development of the Social Brain in Adolescence. J. R. Soc. Med. 2012, 105, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, O.; Ban, S. Adolescence: Physical Changes and Neurological Development. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silén, Y.; Keski-Rahkonen, A. Worldwide Prevalence of DSM-5 Eating Disorders among Young People. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2022, 35, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onofri, A.; Pensato, U.; Rosignoli, C.; Wells-Gatnik, W.; Stanyer, E.; Ornello, R.; Chen, H.Z.; De Santis, F.; Torrente, A.; Mikulenka, P.; et al. Primary Headache Epidemiology in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Headache Pain 2023, 24, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipriano, A.; Cella, S.; Cotrufo, P. Nonsuicidal Self-Injury: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guidetti, V.; Faedda, N.; Siniatchkin, M. Migraine in Childhood: Biobehavioural or Psychosomatic Disorder? J. Headache Pain 2016, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szperka, C. Headache in Children and Adolescents. Continuum 2021, 27, 703–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juli, M.R.; Juli, L. Body Identity Search: The Suspended Body. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hornberger, L.L.; Lane, M.A. Committee on Adolescence Identification and Management of Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 2021, 147, e2020040279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, F.; Alvarez-Mon, M.A.; Fernandez-Rojo, S.; Ortega, M.A.; Felix-Alcantara, M.P.; Morales-Gil, I.; Rodriguez-Quiroga, A.; Alvarez-Mon, M.; Quintero, J. Psychosocial Factors in Adolescence and Risk of Development of Eating Disorders. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Harms, J.; Chen, E.; Gao, P.; Xu, P.; He, Y. Current Discoveries and Future Implications of Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, R.; Kaess, M.; Parzer, P.; Fischer, G.; Carli, V.; Hoven, C.W.; Wasserman, C.; Sarchiapone, M.; Resch, F.; Apter, A.; et al. Life-Time Prevalence and Psychosocial Correlates of Adolescent Direct Self-Injurious Behavior: A Comparative Study of Findings in 11 European Countries. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, A.L.; Prosek, E.A.; Schmit, E.L.; Schmit, M.K. Examining Coping and Nonsuicidal Self-Injury among Adolescents: A Profile Analysis. J. Couns. Dev. 2023, 101, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davico, C.; Amianto, F.; Gaiotti, F.; Lasorsa, C.; Peloso, A.; Bosia, C.; Vesco, S.; Arletti, L.; Reale, L.; Vitiello, B. Clinical and Personality Characteristics of Adolescents with Anorexia Nervosa with or without Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Behavior. Compr. Psychiatry 2019, 94, 152115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colman, I.; Kingsbury, M.; Sareen, J.; Bolton, J.; van Walraven, C. Migraine Headache and Risk of Self-Harm and Suicide: A Population-Based Study in Ontario, Canada. Headache 2016, 56, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira-Souza, A.I.S.; da Silva Freitas, D.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Raposo, M.C.F.; de Oliveira, D.A. The Presence of Migraine Symptoms Was Associated with a Higher Likelihood to Present Eating Disorders Symptoms among Teenage Students. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2022, 27, 1661–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornstein, R.F.; Hopwood, C.J. Multimethod Clinical Assessment: Retrospect and Prospect. In Multimethod Clinical Assessment; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, G.J.; Viglione, D.J.; Mihura, J.L.; Erard, R.E.; Erdberg, P. Rorschach Performance Assessment System: Administration, Coding, Interpretation, and Technical Manual; Rorschach Performance Assessment System, LLC: Toledo, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, G.J.; Hilsenroth, M.J.; Baxter, D.; Exner, J.E.; Fowler, J.C.; Piers, C.C.; Resnick, J. An Examination of Interrater Reliability for Scoring the Rorschach Comprehensive System in Eight Data Sets. J. Pers. Assess. 2002, 78, 219–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianowski, G.; Meyer, G.J.; de Villemor-Amaral, A.E.; Zuanazzi, A.C.; do Nascimento, R.S.G.F. Does the Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS) Differ from the Comprehensive System (CS) on Variables Relevant to Interpretation? J. Pers. Assess. 2021, 103, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglione, D.J.; de Ruiter, C.; King, C.M.; Meyer, G.J.; Kivisto, A.J.; Rubin, B.A.; Hunsley, J. Legal Admissibility of the Rorschach and R-PAS: A Review of Research, Practice, and Case Law. J. Pers. Assess. 2022, 104, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, G.J.; Eblin, J.J. An Overview of the Rorschach Performance Assessment System (R-PAS). Psychol. Inj. Law. 2012, 5, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Participants. JAMA 2025, 333, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensi, M.M. 20240808_PSY_HRN_MMM_01 2024.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd Edition (Beta Version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Axelson, D.; Pereplitchikova, F.; Brent, D.; Ryan, N.; Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Axelson, D.; Pereplitchikova, F.; et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children: Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) DSM-5; Child and Adolescent Research and Education: New Heaven, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV); Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali, Ed.; Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali, Ed.; Giunti Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Rao, U.; Ryan, N.; Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Rao, U.; Ryan, N.; A Cura Di Sogos, C.; Di Noia, S.P.; et al. 2019 K-SADS-PL DSM-5 Intervista Diagnostica per La Valutazione Dei Disturbi Psicopatologici in Bambini e Adolescenti. In Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children: Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) DSM-5; Erickson, Ed.; Erickson: Trento, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- First, M.; Williams, J.; Karg, R.; First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV); American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, A.R.; Yung, A.R.; Pan Yuen, H.; Mcgorry, P.D.; Phillips, L.J.; Kelly, D.; Dell’olio, M.; Francey, S.M.; Cosgrave, E.M.; Killackey, E.; et al. Mapping the Onset of Psychosis: The Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2005, 39, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, W. CGI Clinical Global Impressions. In EC-DEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology; US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration/National Institute of Mental Health, Psychopharmacology Research Branch, Division of Extramural Research Programs: Rockville, MD, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, D.; Gould, M.S.; Brasic, J.; Ambrosini, P.; Fisher, P.; Bird, H.; Aluwahlia, S. A Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1983, 40, 1228–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybarczyk, B. Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS). In Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology; Kreutzer, J.S., DeLuca, J., Caplan, B., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; p. 2313. ISBN 978-0-387-79948-3. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 30.0.0.0; IBM Corp.: Armonk, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kroes, A.D.A.; Finley, J.R. Demystifying Omega Squared: Practical Guidance for Effect Size in Common Analysis of Variance Designs. Psychol. Methods 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.L.L.; Erickson, M.L. On Dummy Variable Regression Analysis: A Description and Illustration of the Method. Sociol. Methods Res. 1974, 2, 409–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgman, S.; Ericsson, I.; Clausson, E.K.; Garmy, P. The Relationship Between Reported Pain and Depressive Symptoms Among Adolescents. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020, 36, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falla, K.; Kuziek, J.; Mahnaz, S.R.; Noel, M.; Ronksley, P.E.; Orr, S.L. Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms and Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Migraine. JAMA Pediatr. 2022, 176, 1176–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazerani, P. Migraine and Mood in Children. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hommer, R.; Lateef, T.; He, J.-P.; Merikangas, K. Headache and Mental Disorders in a Nationally Representative Sample of American Youth. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 2022, 31, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, E.; Kazemizadeh, H.; Togha, M.; Haghighi, S.; Salami, Z.; Shahamati, D.; Martami, F.; Baigi, V.; Etesam, F. The Influence of Anxiety and Depression on Headache in Adolescent Migraineurs: A Case-Control Study. Expert. Rev. Neurother. 2022, 22, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Chang, M. Associations Between Headache (Migraine and Tension-Type Headache) and Psychological Symptoms (Depression and Anxiety) in Pediatrics: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain. Physician 2023, 26, E617–E626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gozubatik-Celik, R.G.; Ozturk, M. Evaluation of Quality of Life and Anxiety Disorder in Children and Adolescents with Primary Headache. Med. Bull. Haseki Haseki Tip. Bulteni 2021, 59, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minen, M.T.; Dhaem, O.B.D.; Diest, A.K.V.; Powers, S.; Schwedt, T.J.; Lipton, R.; Silbersweig, D. Migraine and Its Psychiatric Comorbidities. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitherman, T.A.; Kolivas, E.D.; Bailey, J.R. Panic Disorder and Migraine: Comorbidity, Mechanisms, and Clinical Implications. Headache J. Head. Face Pain 2013, 53, 23–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzi, G.; Zambrino, C.; Ferrari-Ginevra, O.; Termine, C.; D’Arrigo, S.; Vercelli, P.; De Silvestri, A.; Guglielmino, C. Personality Traits in Childhood and Adolescent Headache. Cephalalgia 2001, 21, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottiroli, S.; Renzi, A.; Ballante, E.; De Icco, R.; Sances, G.; Tanzilli, A.; Vecchi, T.; Tassorelli, C.; Galli, F. Personality in Chronic Headache: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Pain Res. Manag. 2023, 2023, 6685372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarantino, S.; Proietti Checchi, M.; Papetti, L.; Ursitti, F.; Sforza, G.; Ferilli, M.A.N.; Moavero, R.; Monte, G.; Capitello, T.G.; Vigevano, F.; et al. Interictal Cognitive Performance in Children and Adolescents With Primary Headache: A Narrative Review. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 898626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exner, J.E., Jr. The Rorschach: A Comprehensive System, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. xvi, 680. ISBN 978-0-471-38672-8. [Google Scholar]

- Balottin, L.; Mannarini, S.; Candeloro, D.; Mita, A.; Chiappedi, M.; Balottin, U. Rorschach Evaluation of Personality and Emotional Characteristics in Adolescents With Migraine Versus Epilepsy and Controls. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouteloup, M.; Belot, R.-A.; Mariage, A.; Bonnet, M.; Vuillier, F. The Value of the Rorschach Method in Clinical Assessment of Migraine Patients. Rorschachiana 2020, 41, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, A.; Pepin, G.; Le, A.; Maloney, D.; Aouad, P.; Barakat, S.; Boakes, R.; Brennan, L.; Bryant, E.; Byrne, S.; et al. Psychiatric and Medical Comorbidities of Eating Disorders: Findings from a Rapid Review of the Literature. J. Eat. Disord. 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koyanagi, A.; Stickley, A.; Haro, J.M. Psychotic-like Experiences and Disordered Eating in the English General Population. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 241, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, L.; Lacoua, L.; Eshel, Y.; Stein, D. Changes in Defensiveness and in Affective Distress Following Inpatient Treatment of Eating Disorders: Rorschach Comprehensive System and Self-Report Measures. J. Personal. Assess. 2008, 90, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sander, J.; Moessner, M.; Bauer, S. Depression, Anxiety and Eating Disorder-Related Impairment: Moderators in Female Adolescents and Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanna, V.; Criscuolo, M.; Mereu, A.; Cinelli, G.; Marchetto, C.; Pasqualetti, P.; Tozzi, A.E.; Castiglioni, M.C.; Chianello, I.; Vicari, S. Restrictive Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents: A Comparison between Clinical and Psychopathological Profiles. Eat. Weight. Disord. 2021, 26, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, C.; Stahl, D.; Tchanturia, K. Estimated Intelligence Quotient in Anorexia Nervosa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Literature. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 9, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bills, E.; Greene, D.; Stackpole, R.; Egan, S.J. Perfectionism and Eating Disorders in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Appetite 2023, 187, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Rogantini, C.; Nacinovich, R.; Riva, A.; Provenzi, L.; Chiappedi, M.; Balottin, U.; Borgatti, R. Clinical Features of Adolescents Diagnosed with Eating Disorders and at Risk for Psychosis. Eur. Psychiatry 2020, 63, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibon-Czopp, S.; Weiner, I.B. Rorschach Assessment of Adolescents. Theory, Research, and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guinzbourg de Braude, S.M.; Vibert, S.; Righetti, T.; Antonelli, A. Eating Disorders and the Rorschach. Rorschachiana 2021, 42, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froreich, F.V.; Vartanian, L.R.; Grisham, J.R.; Touyz, S.W. Dimensions of Control and Their Relation to Disordered Eating Behaviours and Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms. J. Eat. Disord. 2016, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzola, E.; Abbate-Daga, G.; Gramaglia, C.; Amianto, F.; Fassino, S. A Qualitative Investigation into Anorexia Nervosa: The Inner Perspective. Cogent Psychol. 2015, 2, 1032493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balottin, L.; Mannarini, S.; Mensi, M.M.; Chiappedi, M.; Balottin, U. Are Family Relations Connected to the Quality of the Outcome in Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa? An Observational Study with the Lausanne Trilogue Play. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2018, 25, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensi, M.M.; Criscuolo, M.; Vai, E.; Rogantini, C.; Orlandi, M.; Ballante, E.; Zanna, V.; Mazzoni, S.; Balottin, U.; Borgatti, R. Perceived and Observed Family Functioning in Adolescents Affected by Restrictive Eating Disorders. Fam. Relat. 2022, 71, 724–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minuchin, S.; Rosman, B.L.; Baker, L.; Liebman, R. Psychosomatic Families; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Yin, X.; Pan, B.; Chen, H.; Dai, C.; Tong, C.; Chen, F.; Feng, X. Understanding Comorbidity Between Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Depressive Symptoms in a Clinical Sample of Adolescents: A Network Analysis. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2024, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielscher, E.; DeVylder, J.; Hasking, P.; Connell, M.; Martin, G.; Scott, J.G. Can’t Get You out of My Head: Persistence and Remission of Psychotic Experiences in Adolescents and Its Association with Self-Injury and Suicide Attempts. Schizophr. Res. 2021, 229, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, L.R.; de Neve-Enthoven, N.G.M.; João, A.M.; Bouter, D.C.; Hillegers, M.H.J.; Hoogendijk, W.J.G.; Blanken, L.M.E.; Kushner, S.A.; Tiemeier, H.; Grootendorst-van Mil, N.H.; et al. Psychotic Experiences, Suicidality and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Adolescents: Independent Findings from Two Cohorts. Schizophr. Res. 2023, 257, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hong, L.; Tong, S.; Li, M.; Sun, S.; Xu, Y.; Liu, J.; Feng, T.; Li, Y.; Lin, G.; et al. Cognitive Impairment and Factors Influencing Depression in Adolescents with Suicidal and Self-Injury Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stead, V.E.; Boylan, K.; Schmidt, L.A. Longitudinal Associations between Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Borderline Personality Disorder in Adolescents: A Literature Review. Borderline Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2019, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, A.; Hasking, P.; Claes, L.; McEvoy, P. Big Five Personality Clusters in Relation to Nonsuicidal Self-Injury. Arch. Suicide Res. 2021, 25, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somma, A.; Fossati, A.; Ferrara, M.; Fantini, F.; Galosi, S.; Krueger, R.F.; Markon, K.E.; Terrinoni, A. DSM-5 Personality Domains as Correlates of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Severity in an Italian Sample of Adolescent Inpatients with Self-Destructive Behaviour. Personal. Ment. Health 2019, 13, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghinea, D.; Fuchs, A.; Parzer, P.; Koenig, J.; Resch, F.; Kaess, M. Psychosocial Functioning in Adolescents with Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Roles of Childhood Maltreatment, Borderline Personality Disorder and Depression. Borderline Pers. Disord. Emot. Dysregulation 2021, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, S.; Kogayu, N.; Ono, S. Persistence and Cessation of Nonsuicidal Self-Injury under Psychotherapy. Rorschachiana 2024, 45, 64–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochinski, S.; Smith, S.R.; Baity, M.R.; Hilsenroth, M.J. Rorschach Correlates of Adolescent Self-Mutilation. Bull. Menn. Clin. 2008, 72, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, L. Relationship Between Loneliness, Hopelessness, Coping Style, and Mobile Phone Addiction Among Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Adolescents. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 3573–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, M.; Messina, A.; Monda, V.; Bitetti, I.; Salerno, F.; Precenzano, F.; Pisano, S.; Salvati, T.; Gritti, A.; Marotta, R.; et al. The Rorschach Test Evaluation in Chronic Childhood Migraine: A Preliminary Multicenter Case–Control Study. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 3573–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Íñigo, A.-P.; Germán, M.-H.; Dolores, S.-G.M.; Marina, F.-F.; Pilar, P.-O.M.D.; Marina, D.-M.; Luis, C.-P.J. Narcissism as a Protective Factor against the Risk of Self-Harming Behaviors without Suicidal Intention in Borderline Personality Disorder. Actas Españolas Psiquiatr. 2023, 51, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Moselli, M.; Casini, M.P.; Frattini, C.; Williams, R. Suicidality and Personality Pathology in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Child. Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2023, 54, 290–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mar, J.; Larrañaga, I.; Ibarrondo, O.; González-Pinto, A.; Hayas, C.L.; Fullaondo, A.; Izco-Basurko, I.; Alonso, J.; Mateo-Abad, M.; de Manuel, E.; et al. Socioeconomic and Gender Inequalities in Mental Disorders among Adolescents and Young Adults. Span. J. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 17, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | a–b | a–c | b–c | Contrast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ω2 | p | p | p | |||

| K-SADS-PL | Depression | 9.940 | <0.001 *** | 0.230 | 0.023 * | <0.001 *** | 0.761 | a < b; a < c |

| Psychosis | 3.279 | 0.045 * | 0.071 | 0.261 | 0.050 * | 1.000 | a < c | |

| Social anxiety | 5.987 | 0.004 ** | 0.143 | 0.329 | 0.004 ** | 0.329 | a < c | |

| OCD | 3.279 | 0.045 * | 0.071 | 1.000 | 0.261 | 0.050 * | b > c | |

| AN | 25.333 | <0.001 *** | 0.448 | <0.001 *** | 0.206 | <0.001 *** | a < b; b > c | |

| IQ | WMI | 8.117 | 0.017 * | 0.040 | 0.582 | 0.013 * | 0.392 | a < c |

| SCID-5 PD a | Borderline | 9.274 | <0.001 ** | 0.252 | 1.000 | 0.001 *** | 1.000 | a < c |

|

Negative Symptoms | 8.398 | <0.001 *** | 0.243 | 0.031 * | 0.001 *** | 0.904 | a < b; a < c | |

| CGI-S | 16.300 | <0.001 *** | 0.338 | 0.003 ** | <0.001 *** | 0.491 | a < b; a < c | |

| CGAS | 5.686 | 0.006 ** | 0.135 | 0.565 | 0.004 ** | 0.144 | a > c | |

| SOFAS | 5.005 | 0.010 ** | 0.118 | 1.000 | 0.015 ** | 0.045 * | a > c; b > c | |

| a–b | a–c | b–c | Contrast | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ω2 | p | p | p | ||

| PHR/GPHR 1 | 5.098 | 0.009 ** | 0.132 | 0.014 * | 0.044 * | 1.000 | a < b; a < c |

| W% 2 | 4.855 | 0.011 * | 0.114 | 0.013 * | 0.082 | 1.000 | a > b |

| Dd% 3 | 15.64 | <0.001 *** | 0.328 | <0.001 *** | 0.002 ** | 0.168 | a < b; a < c |

| Cblend 4 | 8.318 | 0.016 * | 0.063 | 0.688 | 0.284 | 0.012 * | b < c |

| C′ 5 | 6.633 | 0.036 * | 0.088 | 1.000 | 0.267 | 0.035 * | b > c |

| NPH/SumH 6 | 4.475 | 0.016 * | 0.114 | 0.093 | 1.000 | 0.020 * | b > c |

| PER 7 | 8.203 | 0.017 * | 0.095 | 1.000 | 0.047 * | 0.033 * | a < c; b < c |

| Model | R | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Std. Error of the Estimate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔR2 | F Change | df1 | df2 | p | |||||

| 1 | 0.561 a | 0.315 | 0.296 | 0.638 | 0.315 | 16.109 | 1 | 35 | <0.001 ** |

| 2 | 0.800 b | 0.639 | 0.618 | 0.470 | 0.324 | 30.574 | 1 | 34 | <0.001 ** |

| 3 | 0.829 c | 0.688 | 0.659 | 0.444 | 0.048 | 5.101 | 1 | 33 | 0.031 * |

| Model | Variable | B | Standard Error | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Constant | 0.733 | 0.165 | - | 4.451 | <0.001 ** |

| Negative symptoms | 0.858 | 0.214 | 0.561 | 4.014 | <0.001 ** | |

| 2 | Constant | 0.273 | 0.147 | - | 1.854 | 0.072 |

| Negative symptoms | 0.965 | 0.158 | 0.632 | 6.087 | <0.001 ** | |

| SCID-5 PD borderline | 0.863 | 0.156 | 0.574 | 5.529 | <0.001 ** | |

| 3 | Constant | 0.198 | 0.143 | - | 1.382 | 0.176 |

| Negative symptoms | 0.944 | 0.150 | 0.618 | 6.293 | <0.001 ** | |

| SCID-5 PD borderline | 0.783 | 0.152 | 0.520 | 5.155 | <0.001 ** | |

| K-SADS-PL psychosis symptoms | 0.355 | 0.157 | 0.226 | 2.258 | 0.031 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pratile, D.C.; Orlandi, M.; Carpani, A.; Mensi, M.M. Look at My Body: It Tells of Suffering—Understanding Psychiatric Pathology in Patients Who Suffer from Headaches, Restrictive Eating Disorders, or Non-Suicidal Self-Injuries (NSSIs). Pediatr. Rep. 2025, 17, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17010021

Pratile DC, Orlandi M, Carpani A, Mensi MM. Look at My Body: It Tells of Suffering—Understanding Psychiatric Pathology in Patients Who Suffer from Headaches, Restrictive Eating Disorders, or Non-Suicidal Self-Injuries (NSSIs). Pediatric Reports. 2025; 17(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17010021

Chicago/Turabian StylePratile, Diletta Cristina, Marika Orlandi, Adriana Carpani, and Martina Maria Mensi. 2025. "Look at My Body: It Tells of Suffering—Understanding Psychiatric Pathology in Patients Who Suffer from Headaches, Restrictive Eating Disorders, or Non-Suicidal Self-Injuries (NSSIs)" Pediatric Reports 17, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17010021

APA StylePratile, D. C., Orlandi, M., Carpani, A., & Mensi, M. M. (2025). Look at My Body: It Tells of Suffering—Understanding Psychiatric Pathology in Patients Who Suffer from Headaches, Restrictive Eating Disorders, or Non-Suicidal Self-Injuries (NSSIs). Pediatric Reports, 17(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric17010021