Barriers to and Facilitators of Providing Care for Adolescents Suffering from Rare Diseases: A Mixed Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

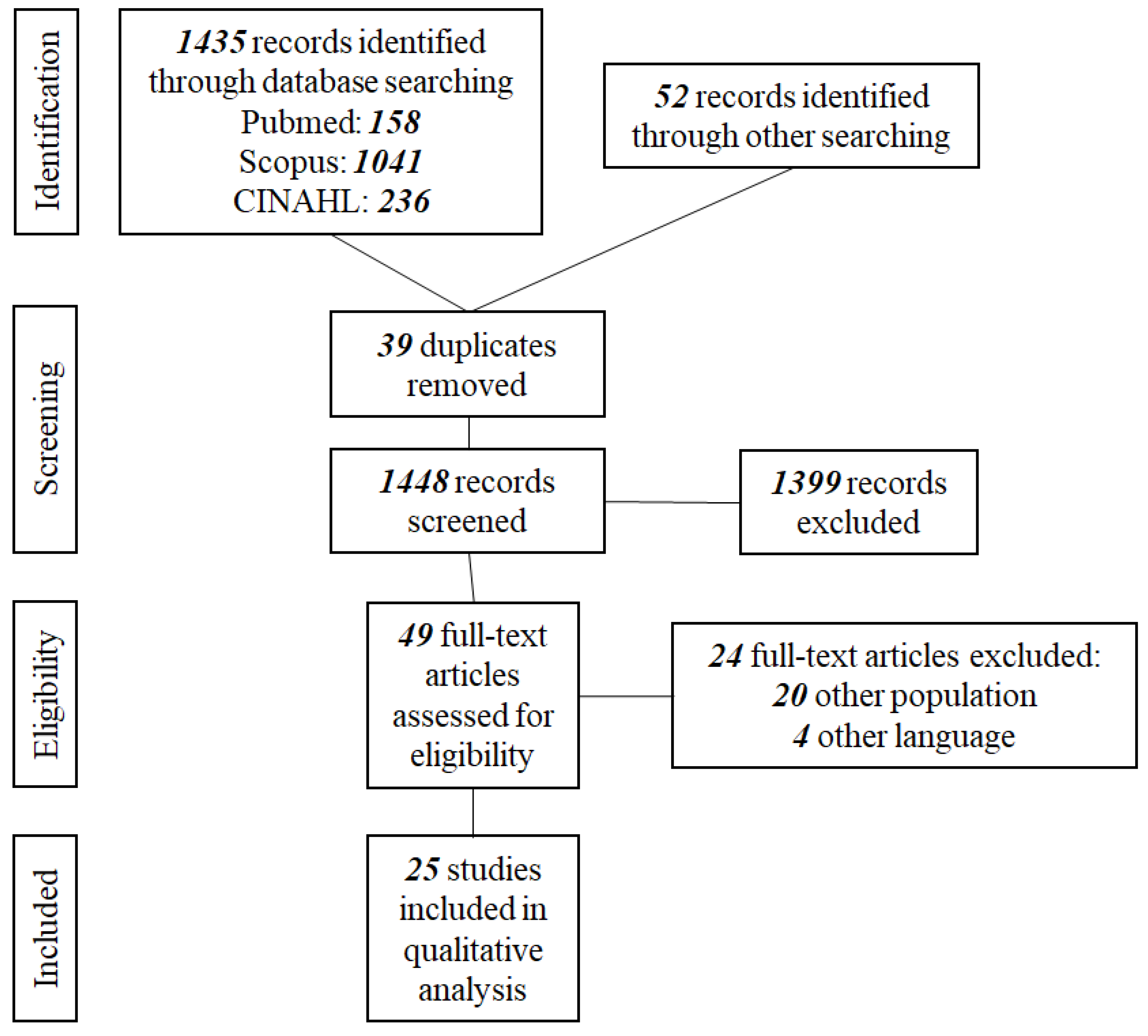

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Review Questions

- What are the perceptions of adolescents with RDs about the provision of healthcare?

- Are they satisfied, or do they recognize barriers and facilitators?

- What do their parents think of the existing healthcare provision?

- What do the parents view as barriers and facilitators?

- Which healthcare strategies and/or interventions are reported to have a positive impact on the quality of life (QL) and health-related quality of life (HRQL) of adolescent patients and their parents?

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

- Population: Adolescents suffering from Rare Diseases with an established diagnosis and their parents. There were no geographical or socioeconomic limitations.

- Phenomena of interest: Barriers and facilitators regarding healthcare provision.

- Context: All aspects of healthcare provision (structures, processes and outcomes) in all healthcare settings (inpatient, outpatient, primary, secondary or tertiary).

- Peer-reviewed English publications.

- Original papers.

- Participants included adolescents and their parents describing experiences in the healthcare system.

- Qualitative, quantitative or mixed methodologies.

- Potentially relevant to the research questions.

2.4. Definitions

2.5. Conceptual Framework

2.6. Search Strategy

2.7. Study Screening

2.8. Quality Assessment

2.9. Data Extraction

2.10. Data Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Identification Characteristics and Synthesis of Key Findings

3.2. Barriers and Facilitators to Optimal Healthcare for Adolescents with RDs

3.2.1. Intrapersonal Level

3.2.2. Interpersonal Level

3.2.3. Institutional/Organizational Level

Structures

Processes

Outcomes

3.2.4. Community Level

3.2.5. Public and Policy Level

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | Key Words |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (((((rare disease*[Title/Abstract]) OR (orphan disease*[Title/Abstract])) OR (rare disorder*[Title/Abstract])) OR (orphan disorder*[Title/Abstract])) AND (((((barriers[Title/Abstract]) OR (obstacles[Title/Abstract])) OR (difficulties[Title/Abstract])) OR (facilitators[Title/Abstract])) OR (enablers[Title/Abstract]))) AND (((((healthcare provision[Title/Abstract]) OR (structures[Title/Abstract])) OR (processes[Title/Abstract])) OR (outcomes[Title/Abstract])) OR (healthcare settings[Title/Abstract])) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (“rare diseases” OR “orphan diseases” OR “rare disorders” OR “orphan disorders”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (barriers OR obstacles OR difficulties OR facilitators OR enablers) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“healthcare provision” OR structures OR processes OR outcomes OR “healthcare settings”)) |

| CINAHL | ((“rare diseases” or “orphan diseases” or “rare disorders” or “orphan disorders”) and (barriers or obstacles or difficulties or facilitators or enablers) and (“healthcare provision” or structures or processes or outcomes or “healthcare settings”)) |

| Study | Is the Qualitative Approach Appropriate to Answer the Research Question? | Are the Qualitative Data Collection Methods Adequate to Address the Research Question? | Are the Findings Adequately Derived from the Data? | Is the Interpretation of Results Sufficiently Substantiated by Data? | Is There Coherence between Qualitative Data Sources, Collection, Analysis and Interpretation? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baumbusch (2018) [12] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Bogart (2014) [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Cardinali (2019) [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Currie and Szabo (2019) [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Currie and Szabo (2019) [13] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Damen (2022) [51] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gómez-Zúñiga (2019) [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Hanson (2018) [53] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Huyard (2009) [47] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Palacios-Ceña (2018) [49] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pasquini (2021) [55] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Sisk (2022) [56] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Smits (2022) [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Somanadhan and Larkin (2016) [41] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Verger (2021) [31] | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y |

| Vines (2018) [32] | Y | Y | Y | CT | Y |

| Witt (2019) [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Study | Are the Participants Representative of the Target Population? | Are Measurements Appropriate Regarding Both the Outcome and Intervention (or Exposure)? | Are There Complete Outcome Data? | Are the Confounders Accounted for in the Design and Analysis? | During the Study Period, Is the Intervention Administered (or Exposure Occurred) as Intended? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adama (2021) [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Boettcher (2020) [50] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gao (2020) [57] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Geerts (2008) [52] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Gimenez-Lozano (2022) [11] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Magliano (2013) [48] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Study | Is There an Adequate Rationale for Using a Mixed Methods Design to Address the Research Question? | Are the Different Components of the Study Effectively Integrated to Answer the Research Question? | Are the Outputs of the Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Components Adequately Interpreted? | Are Divergences and Inconsistencies between Quantitative and Qualitative Results Adequately Addressed? | Do the Different Components of the Study Adhere to the Quality Criteria of Each Tradition of the Methods Involved? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson (2013) [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mazzella (2021) [54] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

References

- Matthews, L.; Chin, V.; Taliangis, M.; Samanek, A.; Baynam, G. Childhood Rare Diseases and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzzatto, L.; Hyry, H.I.; Schieppati, A.; Costa, E.; Simoens, S.; Schaefer, F.; Roos, J.C.P.; Merlini, G.; Kääriäinen, H.; Garattini, S.; et al. Outrageous Prices of Orphan Drugs: A Call for Collaboration. Lancet 2018, 392, 791–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, P.; Gold-von Simson, G. Pharmaceutical Pricing, Cost Containment and New Treatments for Rare Diseases in Children. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2014, 9, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saggu, H.; Jones, C.; Lewis, A.; Baynam, G. MEDUrare: Supporting Integrated Care for Rare Diseases by Better Connecting Health and Education Through Policy. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2021, 94, 693–702. [Google Scholar]

- Bavisetty, S.; Grody, W.W.; Yazdani, S. Emergence of Pediatric Rare Diseases. Rare Dis. 2013, 1, e23579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, J.; Taruscio, D.; Llera, V.A.; Barrera, L.A.; Coté, T.R.; Edfjäll, C.; Gavhed, D.; Haffner, M.E.; Nishimura, Y.; Posada, M.; et al. The Need for Worldwide Policy and Action Plans for Rare Diseases. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiu, M.; Dan, D. Rare Diseases, from European Resolutions and Recommendations to Actual Measures and Strategies. Maedica 2010, 5, 128–131. [Google Scholar]

- Güeita-Rodriguez, J.; Famoso-Pérez, P.; Salom-Moreno, J.; Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Pérez-Corrales, J.; Palacios-Ceña, D. Challenges Affecting Access to Health and Social Care Resources and Time Management among Parents of Children with Rett Syndrome: A Qualitative Case Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. Rare Diseases: Clinical Progress but Societal Stalemate. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, H.; Dammann, B.; Andresen, I.-L.; Fagerland, M.W. Health-Related Quality of Life for Children with Rare Diagnoses, Their Parents’ Satisfaction with Life and the Association between the Two. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2013, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Lozano, C.; Páramo-Rodríguez, L.; Cavero-Carbonell, C.; Corpas-Burgos, F.; López-Maside, A.; Guardiola-Vilarroig, S.; Zurriaga, O. Rare Diseases: Needs and Impact for Patients and Families: A Cross-Sectional Study in the Valencian Region, Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumbusch, J.; Mayer, S.; Sloan-Yip, I. Alone in a Crowd? Parents of Children with Rare Diseases’ Experiences of Navigating the Healthcare System. J. Genet. Couns. 2019, 28, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Szabo, J. “It Would Be Much Easier If We Were Just Quiet and Disappeared”: Parents Silenced in the Experience of Caring for Children with Rare Diseases. Health Expect. 2019, 22, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, A.; Bloom, L.; Fulop, N.J.; Hudson, E.; Leeson-Beevers, K.; Morris, S.; Ramsay, A.I.G.; Sutcliffe, A.G.; Walton, H.; Hunter, A. How Are Patients with Rare Diseases and Their Carers in the UK Impacted by the Way Care Is Coordinated? An Exploratory Qualitative Interview Study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, A.; White, H.; Bath-Hextall, F.; Salmond, S.; Apostolo, J.; Kirkpatrick, P. A Mixed-Methods Approach to Systematic Reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z. Software to Support the Systematic Review Process. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2016, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, A.; Smith, J. Mixed Methods Research: Expanding the Evidence Base. Evid. Based Nurs. 2017, 20, 74–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, J.-Y.; Choi, M.-Y. Barriers to and Facilitators of School Health Care for Students with Chronic Disease as Perceived by Their Parents: A Mixed Systematic Review. Healthcare 2020, 8, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach-Mortensen, A.M.; Verboom, B. Barriers and Facilitators Systematic Reviews in Health: A Methodological Review and Recommendations for Reviewers. Res. Synth. Methods 2020, 11, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flottorp, S.A.; Oxman, A.D.; Krause, J.; Musila, N.R.; Wensing, M.; Godycki-Cwirko, M.; Baker, R.; Eccles, M.P. A Checklist for Identifying Determinants of Practice: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Frameworks and Taxonomies of Factors That Prevent or Enable Improvements in Healthcare Professional Practice. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derayeh, S.; Kazemi, A.; Rabiei, R.; Hosseini, A.; Moghaddasi, H. National Information System for Rare Diseases with an Approach to Data Architecture: A Systematic Review. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2018, 7, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.A.; Siddiqi, M.; Parameshwar, P.; Chandra-Mouli, V. World Health Organization Guidance on Ethical Considerations in Planning and Reviewing Research Studies on Sexual and Reproductive Health in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 64, 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, C. Transition of Care in Children with Chronic Disease. BMJ 2007, 334, 1231–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golden, S.D.; Earp, J.A.L. Social Ecological Approaches to Individuals and Their Contexts. Health Educ. Behav. 2012, 39, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, C.; Aymé, S. Rare Disease Policies to Improve Care for Patients in Europe. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2015, 1852, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameh, S.; Gómez-Olivé, F.X.; Kahn, K.; Tollman, S.M.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K. Relationships between Structure, Process and Outcome to Assess Quality of Integrated Chronic Disease Management in a Rural South African Setting: Applying a Structural Equation Model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care. Milbank Q. 2005, 83, 691–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsani, P.; Katsaras, G. Barriers to and Facilitators of Providing Healthcare for Adolescents Suffering from Rare Diseases: A Mixed Systematic Review. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42023422686 (accessed on 17 June 2023).

- Verger, S.; Negre, F.; Fernández-Hawrylak, M.; Paz-Lourido, B. The Impact of the Coordination between Healthcare and Educational Personnel on the Health and Inclusion of Children and Adolescents with Rare Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vines, E.E.; Fisher, P.; Conniff, H.; Young, J. Adolescents’ Experiences of Isolation in Cystic Fibrosis. Clin. Pract. Pediatr. Psychol. 2018, 6, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, S.; Kolb, B.; Bloemeke, J.; Mohnike, K.; Bullinger, M.; Quitmann, J. Quality of Life of Children with Achondroplasia and Their Parents—A German Cross-Sectional Study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adama, E.A.; Arabiat, D.; Foster, M.J.; Afrifa-Yamoah, E.; Runions, K.; Vithiatharan, R.; Lin, A. The Psychosocial Impact of Rare Diseases among Children and Adolescents Attending Mainstream Schools in Western Australia. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Elliott, E.J.; Zurynski, Y.A. Australian Families Living with Rare Disease: Experiences of Diagnosis, Health Services Use and Needs for Psychosocial Support. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerboeter, M.; Boettcher, J.; Barkmann, C.; Zapf, H.; Nazarian, R.; Wiegand-Grefe, S.; Reinshagen, K.; Boettcher, M. Quality of Life and Mental Health of Children with Rare Congenital Surgical Diseases and Their Parents during the {COVID}-19 Pandemic. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, K.R. “People Are All about Appearances”: A Focus Group of Teenagers with Moebius Syndrome. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 1579–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinali, P.; Migliorini, L.; Rania, N. The Caregiving Experiences of Fathers and Mothers of Children With Rare Diseases in Italy: Challenges and Social Support Perceptions. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Szabo, J. “It Is like a Jungle Gym, and Everything Is under Construction”: The Parent’s Perspective of Caring for a Child with a Rare Disease. Child. Care. Health Dev. 2019, 45, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, R.M.; Vissers, E.; te Pas, R.; Roebbers, N.; Feitz, W.F.J.; van Rooij, I.A.L.M.; de Blaauw, I.; Verhaak, C.M. Common Needs in Uncommon Conditions: A Qualitative Study to Explore the Need for Care in Pediatric Patients with Rare Diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somanadhan, S.; Larkin, P.J. Parents’ Experiences of Living with, and Caring for Children, Adolescents and Young Adults with Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Bujold, M.; Wassef, M. Convergent and Sequential Synthesis Designs: Implications for Conducting and Reporting Systematic Reviews of Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzabonimpa, J.P. Quantitizing and Qualitizing (Im-)Possibilities in Mixed Methods Research. Methodol. Innov. 2018, 11, 2059799118789021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Zúñiga, B.; Moyano, R.P.; Fernández, M.P.; Oliva, A.G.; Ruiz, M.A. The Experience of Parents of Children with Rare Diseases When Communicating with Healthcare Professionals: Towards an Integrative Theory of Trust. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyard, C. What, If Anything, Is Specific about Having a Rare Disorder? Patients’ Judgements on Being Ill and Being Rare. Health Expect. 2009, 12, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliano, L.; Patalano, M.; Sagliocchi, A.; Scutifero, M.; Zaccaro, A.; D’Angelo, M.G.; Civati, F.; Brighina, E.; Vita, G.; Vita, G.L.; et al. “I Have Got Something Positive out of This Situation”: Psychological Benefits of Caregiving in Relatives of Young People with Muscular Dystrophy. J. Neurol. 2014, 261, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Ceña, D.; Famoso-Pérez, P.; Salom-Moreno, J.; Carrasco-Garrido, P.; Pérez-Corrales, J.; Paras-Bravo, P.; Güeita-Rodriguez, J. “Living an Obstacle Course”: A Qualitative Study Examining the Experiences of Caregivers of Children with Rett Syndrome. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boettcher, J.; Denecke, J.; Barkmann, C.; Wiegand-Grefe, S. Quality of Life and Mental Health in Mothers and Fathers Caring for Children and Adolescents with Rare Diseases Requiring Long-Term Mechanical Ventilation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, I.; Schippers, A.; Niemeijer, A.; Abma, T. Living with a Rare Disease as a Family: A Co-Constructed Autoethnography from a Mother. Disabilities 2022, 2, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerts, E.; van de Wiel, H.; Tamminga, R. A Pilot Study on the Effects of the Transition of Paediatric to Adult Health Care in Patients with Haemophilia and in Their Parents: Patient and Parent Worries, Parental Illness-Related Distress and Health-Related Quality of Life. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, C.S.; Newsom, J.; Singh-Grewal, D.; Henschke, N.; Patterson, M.; Tong, A. Children and Adolescents’ Experiences of Primary Lymphoedema: Semistructured Interview Study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2018, 103, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzella, A.; Curry, M.; Belter, L.; Cruz, R.; Jarecki, J. “I Have SMA, SMA Doesn’t Have Me”: A Qualitative Snapshot into the Challenges, Successes, and Quality of Life of Adolescents and Young Adults with SMA. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquini, T.L.S.; Goff, S.L.; Whitehill, J.M. Navigating the U.S. Health Insurance Landscape for Children with Rare Diseases: A Qualitative Study of Parents’ Experiences. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisk, B.A.; Kerr, A.; King, K.A. Factors Affecting Pathways to Care for Children and Adolescents with Complex Vascular Malformations: Parental Perspectives. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Q.; Wang, S.; Ren, J.; Wen, X. Measuring Parent Proxy-Reported Quality of Life of 11 Rare Diseases in Children in Zhejiang, China. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Ghazinour, M.; Hammarström, A. Different Uses of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory in Public Mental Health Research: What Is Their Value for Guiding Public Mental Health Policy and Practice? Soc. Theory Health 2018, 16, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, J.; Choi, M.; Lee, H. School Nurses’ Perceptions Regarding Barriers and Facilitators in Caring for Children with Chronic Diseases in School Settings: A Mixed Studies Review. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyon, M.E.; Wiener, L. Special Issue: Psychosocial Considerations for Children and Adolescents Living with a Rare Disease. Children 2022, 9, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, H.; Simpson, A.; Ramsay, A.I.G.; Hudson, E.; Hunter, A.; Jones, J.; Ng, P.L.; Leeson-Beevers, K.; Bloom, L.; Kai, J.; et al. Developing a Taxonomy of Care Coordination for People Living with Rare Conditions: A Qualitative Study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogart, K.; Hemmesch, A.; Barnes, E.; Blissenbach, T.; Beisang, A.; Engel, P.; Tolar, J.; Schacker, T.; Schimmenti, L.; Brown, N.; et al. Healthcare Access, Satisfaction, and Health-Related Quality of Life among Children and Adults with Rare Diseases. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epps, C.; Bax, R.; Croker, A.; Green, D.; Gropman, A.; Klein, A.V.; Landry, H.; Pariser, A.; Rosenman, M.; Sakiyama, M.; et al. Global Regulatory and Public Health Initiatives to Advance Pediatric Drug Development for Rare Diseases. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2022, 56, 964–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, A.; Larson, S.; Carek, P.; Peabody, M.R.; Peterson, L.E.; Mainous, A.G. Prevalence and Practice for Rare Diseases in Primary Care: A National Cross-Sectional Study in the USA. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e027248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Burgos, S.; Abarca-Barriga, H. Knowledge Level of Medical Students and Physicians about Rare Diseases in Lima, Peru. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2022, 11, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumiene, B.; Peters, H.; Melegh, B.; Peterlin, B.; Utkus, A.; Fatkulina, N.; Pfliegler, G.; Graessner, H.; Hermanns, S.; Scarpa, M.; et al. Rare Disease Education in Europe and beyond: Time to Act. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hone, T.; Macinko, J.; Millett, C. Revisiting Alma-Ata: What Is the Role of Primary Health Care in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Lancet 2018, 392, 1461–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, N.; Turner, J.; Marron, R.; Lambert, D.M.; Murphy, D.N.; O’Sullivan, G.; Mason, M.; Broderick, F.; Burke, M.C.; Casey, S.; et al. The Role of Primary Care in Management of Rare Diseases in Ireland. Irish J. Med. Sci. 2020, 189, 771–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, M.T.; Koch, V.H.; Sarrubbi-Junior, V.; Gallo, P.R.; Carneiro-Sampaio, M. Difficulties in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Rare Diseases According to the Perceptions of Patients, Relatives and Health Care Professionals. Clinics 2018, 73, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.-L.; Baty, F.; Rassouli, F.; Bilz, S.; Brutsche, M.H. Diagnostic Precision and Identification of Rare Diseases Is Dependent on Distance of Residence Relative to Tertiary Medical Facilities. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, K.; Millis, N.; Jaffe, A.; Zurynski, Y. Rare Diseases Research and Policy in Australia: On the Journey to Equitable Care. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 57, 778–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belzer, L.T.; Wright, S.M.; Goodwin, E.J.; Singh, M.N.; Carter, B.S. Psychosocial Considerations for the Child with Rare Disease: A Review with Recommendations and Calls to Action. Children 2022, 9, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, A.P.; Baker, M. The Impact of Parent Advocacy Groups, the Internet, and Social Networking on Rare Diseases: The IDEA League and IDEA League United Kingdom Example. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 102–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depping, M.K.; Uhlenbusch, N.; von Kodolitsch, Y.; Klose, H.F.E.; Mautner, V.-F.; Löwe, B. Supportive Care Needs of Patients with Rare Chronic Diseases: Multi-Method, Cross-Sectional Study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, E.C.; Lewkowicz, C.; Young, M.H. Shared Vision: Concordance Among Fathers, Mothers, and Pediatricians About Unmet Needs of Children with Chronic Health Conditions. Pediatrics 2000, 105, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, R.; Senecat, J.; de Chalendar, M.; Vajda, I.; Dan, D.; Boncz, B. Bridging the Gap between Health and Social Care for Rare Diseases: Key Issues and Innovative Solutions. In Rare Diseases Epidemiology: Update and Overview; Posada De La Paz, M., Taruscio, D., Groft, S.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 1031, pp. 605–627. ISBN 978-3-319-67142-0. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S.; Hudson, E.; Bloom, L.; Chitty, L.S.; Fulop, N.J.; Hunter, A.; Jones, J.; Kai, J.; Kerecuk, L.; Kokocinska, M.; et al. Co-Ordinated Care for People Affected by Rare Diseases: The CONCORD Mixed-Methods Study. Health Soc. Care Deliv. Res. 2022, 10, 1–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hébert, R. Applying Integrated Care Systems to Rare Diseases. Expert Opin. Orphan Drugs 2016, 4, 1095–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boettcher, J.; Filter, B.; Denecke, J.; Hot, A.; Daubmann, A.; Zapf, A.; Wegscheider, K.; Zeidler, J.; von der Schulenburg, J.-M.G.; Bullinger, M.; et al. Evaluation of Two Family-Based Intervention Programs for Children Affected by Rare Disease and Their Families—Research Network (CARE-FAM-NET): Study Protocol for a Rater-Blinded, Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Trial in a 2 × 2 Factorial Design. BMC Fam. Pract. 2020, 21, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, L. Supporting Families of Children with Rare and Unique Chromosome Disorders. Res. Pract. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2018, 5, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Perales, R.; Palomares-Ruiz, A.; Ordóñez-García, L.; García-Toledano, E. Rare Diseases in the Educational Field: Knowledge and Perceptions of Spanish Teachers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huml, R.A.; Dawson, J.; Bailey, M.; Nakas, N.; Williams, J.; Kolochavina, M.; Huml, J.R. Accelerating Rare Disease Drug Development: Lessons Learned from Muscular Dystrophy Patient Advocacy Groups. Ther. Innov. Regul. Sci. 2021, 55, 370–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkle, M.; Pines, W.; Saltonstall, P.L. Advocacy Groups and Their Role in Rare Diseases Research. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 686, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, A.M.; O’Boyle, M.; VanNoy, G.E.; Dies, K.A. Emerging Roles and Opportunities for Rare Disease Patient Advocacy Groups. Ther. Adv. Rare Dis. 2023, 4, 26330040231164424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelentsov, L.J.; Fielder, A.L.; Laws, T.A.; Esterman, A.J. The Supportive Care Needs of Parents with a Child with a Rare Disease: Results of an Online Survey. BMC Fam. Pract. 2016, 17, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Country | Type | Participants | Tools | Rare Diseases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adama (2021) [34] | Australia | Cross-sectional | Parents (N: 41) | Parent Stigma Scale (PSC) Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ) Index of Social Competence (ISC) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Musculoskeletal diseases, blood/oncology diseases, chromosomes/genetic or congenital diseases, metabolic disorders, nervous system disorders, immune system disorders |

| Anderson (2013) [35] | Australia | Mixed methods | Families (N: 30) | Health Utilities Index Mark II (HUI-II) Impact on Family scale (IOF) Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children Measure of Function (RAHC MOF) | Genetic metabolic disorders |

| Baumbusch (2018) [12] | Canada | Qualitative | Parents (N: 16) | Semi-structured interviews | Not defined |

| Boettcher (2020) [50] | Germany | Cross-sectional | Families (N: 75) | Ulm Quality of Life Inventory for Parents (ULQIE) Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP) Oslo-Social Support Scale (OSSS-3) Family Assessment Measure (FAM) | Rare Diseases that require mechanical ventilation |

| Bogart (2014) [37] | USA | Qualitative | Adolescents (N: 10) | Eight open-ended questions drawn from previous research | Moebius syndrome |

| Cardinali (2019) [38] | Italy | Qualitative | Parents (N: 15) | Semi-structured interviews | Aicardi syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Arginine succinic aciduria, Chromosome 22 Ring, Fryns syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome (49 XXXXY), Lesch–Nyhan syndrome, Mucolipidosis type III, Prader–Willi syndrome, Rett syndrome, Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome |

| Currie and Szabo (2019) [39] | Canada | Qualitative | Parents (N: 15) | Semi-structured interviews | Genetic diseases, metabolic disorders, nervous system disorders |

| Currie and Szabo (2019) [13] | Canada | Qualitative | Parents (N: 15) | Semi-structured interviews | Neurodevelopmental disorders |

| Damen (2022) [51] | Netherlands | Qualitative | Mother (N: 1) | Personal narrative | Neurofibromatosis type I |

| Gao (2020) [57] | China | Cross-sectional | Parents (N: 651) | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ 4.0 (PedsQL™ 4.0) | Patent ductus arteriosus, infantile agranulocytosis, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, polysyndactyly, Hirschsprung disease, cleft lip and palate, tetralogy of Fallot, myasthenia gravis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, glycogen storage disease, Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| Geerts (2008) [52] | Netherlands | Cross-sectional | Families (Ν: 29) | Johns Hopkins Adult Cystic Fibrosis Program Survey (7-item parent version and 6-item patient version) Haemo-QoL-A, versions for adolescents, adults and their parents Parents’ illness-related distress (van Dongen-Melman) | Hemophilia |

| Gimenez-Lozano (2022) [11] | Spain | Cross-sectional | Families (N: 163) | Semi-structured, self-completed questionnaire with 52 questions | Congenital malformations, genetic disorders, nervous system diseases, metabolic diseases, blood diseases, diseases of the circulatory system, gastrointestinal diseases, disease of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, disease of the eye and its annexes, diseases of the respiratory system, diseases, of the genitourinary system, neurodevelopmental disorders |

| Gómez-Zúñiga (2019) [46] | Spain | Qualitative | Families (N: 10) | Semi-structured interviews | Not defined |

| Hanson (2018) [53] | Australia | Qualitative | Adolescents (N:20) | Semi-structured interviews | Primary lymphoedema |

| Huyard (2009) [47] | France | Qualitative | Parents (N: 15) | Semi-structured interviews | Fragile X syndrome, Cystic fibrosis, Wilson’s disease, mastocytosis, locked-in syndrome, very rare syndromes |

| Magliano (2013) [48] | Italy | Cross-sectional | Parents (N: 494) | Barthel index (BI) Family Problems Questionnaire (FPQ) Social Network Questionnaire (SNQ) | Duchenne, Becker, or limb–girdle muscular dystrophies |

| Mazzella (2021) [54] | Australia | Mixed methods | Adolescents (N: 44) | Quality of Life Survey SMA Health Index instrument (SMA-HI) free text response | Spinal muscular atrophy |

| Palacios-Ceña (2018) [49] | Spain | Qualitative | Parents (N: 31) | In-depth interviews, focus-groups, field notes, personal documents | Rett syndrome |

| Pasquini (2021) [55] | USA | Qualitative | Parents (N: 15) | Semi-structured interviews | Metachromatic leukodystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy |

| Sisk (2022) [56] | USA | Qualitative | Parents (N: 24) | Semi-structured interviews | Complex vascular malformation, overgrowth disorders |

| Smits (2022) [40] | Netherlands | Qualitative | Parents (N: 12) | Questionnaires and subsequent interviews | Genetic diseases |

| Somanadhan and Larkin (2016) [41] | Ireland | Qualitative | Parents (N: 8) | In-depth interviews | Mucopolysaccharidosis |

| Verger (2021) [31] | Spain | Qualitative | Parents (N: 8) | In-depth interviews, focus-groups | Not defined |

| Vines (2018) [32] | UK | Qualitative | Adolescents (N: 9) | Semi-structured interviews | Cystic fibrosis |

| Witt (2019) [33] | Germany | Qualitative | Parents (N: 73); Adolescents (N: 47) | Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ 4.0 (PedsQL™ 4.0) Short-form 8 Questionnaire (SF-8) | Achondroplasia |

| Study | Synthesis of Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Adama (2021) [34] | Parents report high incidence of health-related stigma, bullying and social disorientation for their suffering children. They also refer to limited targeted school-based interventions. The authors propose strategic development of policies in order to address the specific emotional, behavioral, educational and social needs of adolescents with RDs. |

| Anderson (2013) [35] | Parents caring for adolescents with RDs are negatively impacted by delays in diagnosis, lack of easy access to peer support groups, low social awareness and excessive financial burdens. The paper concludes that more analytical studies need to be conducted aiming to optimize healthcare delivery models. |

| Baumbusch (2018) [12] | Parents refer to limited knowledge from key healthcare providers and impeach the State for major systemic issues regarding access to healthcare. The quality of the services provided is considered “questionable”. Parents also suffer from out-of-pocket payments and experience employment difficulties. The article elaborates on the notion of “expert patient” and “expert caregiver” in the absence of formally designated care coordinators. |

| Boettcher (2020) [50] | Parents experience feelings of guilt, anger and depression and detach themselves from their parental role. Mothers’ mental health is severely compromised since they are traditionally the main caregivers of the sick family member. The article highlights the need for psychosocial screening and support for parents of children with RDs. |

| Bogart (2014) [37] | Adolescents with Moebius syndrome describe positive and negative experiences focusing on peer relationships, social engagements and interactions with parents and healthcare personnel. The article suggests targeted interventions in order to raise social awareness and to empower effective coping mechanisms. |

| Cardinali (2019) [38] | The protective role of social support for the parents is well established in academic literature. The complexities of caregiving and associated gender differences are further studied and analyzed. The paper discusses the shortage of structured health policies and the geographical scattering of health institutions for youth with RDs. |

| Currie and Szabo (2019) [39] | Parents encounter gaps in the accessibility to government support and face the hardships of fragmented and high-cost care. They function as advocates, medical navigators and disease managers. The article highlights the need for an integrated approach from networks of healthcare and social support providers. |

| Currie and Szabo (2019) [13] | Parents undergo a sense of silencing and frustration due to their becoming therapists, caregivers and navigators for their medically fragile children. They are also dissatisfied with their interaction with providers. The authors discuss that a holistic healthcare strategy needs to be developed aiming to address discontinuity of care and bad coordination between health and social services. |

| Damen (2022) [51] | The paper follows the storytelling of a mother caring for an adolescent with NF1. She illustrates the impact of the management of the disease in between hospitals, organizations and services for every single family member. The article foregrounds the multilayer burdens in family dynamics when the child suffers from an RD and highlights the deficits of targeted policies. |

| Gao (2020) [57] | Physical activity, mental health and school performance of patients with RDs should be frequently and carefully monitored. The authors point out that research is essential on the treatment, production, implementation and availability of orphan drugs. |

| Geerts (2008) [52] | The transition from pediatric to adult care in the field of RDs is still, in most cases, unorganized and may lead to worsening of the disease and the mental and health deterioration of the parents. The paper argues in favor of the implementation of policies that facilitate all aspects of transition, taking in account the gender identity of the main caregiver. |

| Gimenez-Lozano (2022) [11] | Public resources for the multilayer needs of RD patients are limited and frequently do not cover all services required. The article focuses on deficiencies in the healthcare system and suggests different approaches in regional and national healthcare planning regarding RDs. |

| Gómez-Zúñiga (2019) [46] | Communication between key health providers and the family of the patient is considered crucial to the effective management of the RD. The authors propose an adjustment of “mutual trust” between doctors and family members cultivating availability and empathy. |

| Hanson (2018) [53] | Adolescents with PL struggle with low self-esteem and treatment restrictions. The paper suggests the development of strategies in order to empower young patients to advocate for themselves in societal context. |

| Huyard (2009) [47] | Patients’ experience with RD would be better if doctors exhibited more respect regarding privacy, diagnosis information and disclosure. The paper brings forward the need for policies that enable healthcare professionals to meet their patients’ moral expectations. |

| Magliano (2013) [48] | The task of caregiving for a sick child with RD is dependent on family dynamics and influenced by professional and social support. Parents still remain the main caregivers and coordinators of the RD. The article poses the question of providing models of care that strengthen the parents as advocates and healthcare navigators. |

| Mazzella (2021) [54] | Young RD patients value the support from healthcare personnel who listen to them and take into account their lived experiences, worries and preferences. The authors encapsulate adolescents’ views on schooling, socialization and disease management and suggest more studies that give prominence to the voice of the patients themselves. |

| Palacios-Ceña (2018) [49] | Parents of children with Rett syndrome mention obstacles in diagnosis, health processes and financial management of the RD. The paper indicates more careful planning of health policies, health systems and support policies. |

| Pasquini (2021) [55] | Health insurance experiences of parents of SMA and MLD patients reveal problematic access to multi-level services required and time consuming conversations with insurance representatives. The paper underlines the need for formally designated healthcare professionals as official coordinators of the RD. |

| Sisk (2022) [56] | Parents of children with VM report discrepancies in initial care and maintenance therapeutics for the patients. The authors provide insights to multiple factors that impede optimal care. |

| Smits (2022) [40] | RDs are complex chronic conditions that affect young patients and may contribute negatively to family functioning. Interdisciplinary family-centered models of care are suggested by the authors. |

| Somanadhan and Larkin (2016) [41] | Parents of young MPS patients comment on the range of uncertainties regarding the RD in everyday life. The paper highlights the negative impact of frequent relapses and hospitalizations on the quality of life of the whole family. |

| Verger (2021) [31] | Coordination of healthcare and education is recognized as an area for major improvement. The article argues that professionals of different fields must have a non-stereotyped approach to young people with RDs. |

| Vines (2018) [32] | Adolescents suffering from cystic fibrosis experience isolation as part of the disease’s everyday care in order to protect themselves from cross-infections. This results in rejection from peer groups, low self-esteem and bio-psychological strain. The paper suggests an increase in RD knowledge and awareness and relevant targeted policies. |

| Witt (2019) [33] | Achondroplasia patients and their families suffer from chronic and debilitating consequences. The paper marks the importance of caring for the psychosocial well-being of the entire family as part of managing the RD. |

| Ecological Model of Health-Levels | Studies | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapersonal | Bogart (2015) [37], Hanson (2018) [53], Magliano (2013) [48], Mazzella (2021) [54], Vines (2018) [32] | Limited knowledge of patients and families Limited self and family education Limited self-esteem and stress-coping mechanisms | Information-sharing between parents and doctors, doctors and patients |

| Interpersonal | Anderson (2013) [35], Baumbusch (2018) [12], Boettcher (2020) [50], Bogart (2015) [37], Currie and Szabo (2019) [13], Damen (2022) [51], Gimenez-Lozano (2022) [11], Gómez-Zúñiga (2019) [46], Huyard (2009) [47], Pasquini (2021) [55], Smits (2022) [40], Verger (2021) [31] | Scarce knowledge of healthcare stakeholders (medical and paramedical personnel, community services personnel, insurance representatives and other parties) Lack of awareness of school staff Limited awareness in society groups (schoolmates, peer groups, parents’ relatives, employers and colleagues) | Supported self and parental care Patients’ dynamic groups and advocacy organizations Rare Disease Awareness and Assistance Programs |

| Institutional/ Organizational | Adama (2021) [34], Anderson (2013) [35], Baumbusch (2018) [12], Boettcher (2020) [50], Currie and Szabo (2019) [39], Currie and Szabo (2019) [13], Gao (2020) [57], Geerts (2008) [52], Gimenez-Lozano (2022) [11], Gómez-Zúñiga (2019) [46], Huyard (2009) [47], Mazzella (2021) [54], Palacios-Ceña (2018) [49], Pasquini (2021) [55], Sisk (2022) [56], Smits (2022) [40], Somanadhan and Larkin (2016) [41], Witt (2019) [33] | Structures Lack of genetic laboratories, facilities and tests to establish an early diagnosis Geographically distributed health and social services Centers of expertise mainly placed in tertiary levels of care or non-existent National registries complex, incomplete or non-existent Limited industry conducting research on orphan drugs Shortage of expert professionals in all fields (doctors, nurses, speech therapists, ergo therapists, play therapists, psychologists, technicians, etc.) Processes Limited RD education in general doctors and primary care personnel Lack of protocols/guidelines for clinical management and follow-up Disconnection between primary, secondary and tertiary level of care Information not effectively shared among all professionals involved Outcomes Inequity and inaccessibility in holistic care Dissatisfied parents emotionally and financially burnt out Patients with frequent relapses, hospitalizations, deterioration and unmet needs Mistrust in the healthcare system and the government | Structures Rare Disease Centers of Expertise geographically planned Genetic services and counseling accessible Processes Well-educated physicians, nurses and other professionals National registries taxonomized for each group of diseases linked with appropriate medications’ prescriptions and other treatments Single entry point and official healthcare coordinator Outcomes Better services for patients and optimized health outcomes Psychosocial care for patients and families |

| Community | Baumbusch (2018) [12], Gimenez-Lozano (2022) [11], Pasquini (2021) [55], Verger (2021) [31] | Inadequate communication between family members and local authorities Absence of single entry point and official care coordinator School staff uneducated, absence or inadequacy of school nurses, unsafe school environment | Community-based interventions/Rare Disease Assistance Programs Equipped local health services Educated primary healthcare physicians Designation of formal healthcare coordinator Pragmatic healthcare plan Collaboration with school personnel and school nurses |

| Public and Policy | All 25 selected studies [12,13,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] | Lack of public funding Lack of industry interest due to the scarcity of knowledge and rarity of the disorders Limited university/academic/research funding and programming for RDs Theoretical approaches not linked to actual methods and intervention programs Restricted integration and evaluation policies for healthcare services involved | Public funding Expanding neonatal screening tests Primary healthcare awareness and education Comprehensive healthcare planning starting from first day of diagnosis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tsitsani, P.; Katsaras, G.; Soteriades, E.S. Barriers to and Facilitators of Providing Care for Adolescents Suffering from Rare Diseases: A Mixed Systematic Review. Pediatr. Rep. 2023, 15, 462-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030043

Tsitsani P, Katsaras G, Soteriades ES. Barriers to and Facilitators of Providing Care for Adolescents Suffering from Rare Diseases: A Mixed Systematic Review. Pediatric Reports. 2023; 15(3):462-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030043

Chicago/Turabian StyleTsitsani, Pelagia, Georgios Katsaras, and Elpidoforos S. Soteriades. 2023. "Barriers to and Facilitators of Providing Care for Adolescents Suffering from Rare Diseases: A Mixed Systematic Review" Pediatric Reports 15, no. 3: 462-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030043

APA StyleTsitsani, P., Katsaras, G., & Soteriades, E. S. (2023). Barriers to and Facilitators of Providing Care for Adolescents Suffering from Rare Diseases: A Mixed Systematic Review. Pediatric Reports, 15(3), 462-482. https://doi.org/10.3390/pediatric15030043