Gamsia batmanii sp. nov. Isolated from a Common Bent-Wing Bat and the Review of the Genus Gamsia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Isolation and Cultivation Conditions

2.2. Morphological Observation

2.3. DNA Extraction and Amplification

2.4. Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of the Genus Gamsia

Type Species: Gamsia Columbina (Demelius) Sandoval-Denis, Guarro and Gene

4.2. Placement of the Novel Species, Interspecific Differences and Ecology

4.3. Fungal Dwellers of Bats—Diversity and Significance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wasti, I.G.; Fui, F.S.; Kassim, M.H.S.; Dawood, M.M.; Hasan, N.H.; Subbiah, V.K.; Seelan, J.S.S. Fungi from Dead Arthropods and Bats of Gomantong Cave, Northern Borneo, Sabah (Malaysia). J. Cave Karst Stud. 2020, 82, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, F.; Jurado, V.; Novakova, A.; Alabouvette, C.; Saiz-Jimenez, C. The Microbiology of Lascaux Cave. Microbiology 2010, 156, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, J.R.; Kilpatrick, A.M.; Langwig, K.E. Ecology and Impacts of White-Nose Syndrome on Bats. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 196–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Z.; Jiang, C.Y.; Liu, S.J. Microbial Roles in Cave Biogeochemical Cycling. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 950005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savković, Ž.; Popović, S.; Stupar, M. Unveiling the Subterranean Symphony: A Comprehensive Study of Cave Fungi Revealed through National Center for Biotechnology Sequences. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzoli, L.; Bozzetta, E.; Varello, K.; Cappelleri, A.; Patriarca, E.; Debernardi, P.; Riccucci, M.; Boggero, A.; Girometta, C.; Picco, A.M. White-Nose Syndrome Confirmed in Italy: A Preliminary Assessment of Its Occurrence in Bat Species. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haelewaters, D.; Page, R.A.; Pfister, D.H. Laboulbeniales Hyperparasites (Fungi, Ascomycota) of Bat Flies: Independent Origins and Host Associations. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 8396–8418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burazerović, J.; Jovanović, M.; Savković, Ž.; Breka, K.; Stupar, M. Finding the Right Host in the Darkness of the Cave—New Insights into the Ecology and Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Hyperparasitic Fungi (Arthrorhynchus nycteribiae, Laboulbeniales). Microb. Ecol. 2025, 88, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Zhao, P.; Cai, L. Origin of Cave Fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.O.; Bezerra, J.D.; Oliveira, T.G.; Barbier, E.; Bernard, E.; Machado, A.R.; Souza-Motta, C.M. Living in the Dark: Bat Caves as Hotspots of Fungal Diversity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Dong, Y.; Karasaki, S.; Tibpromma, S.; Hyde, K.D.; Lumyong, S.; Xu, J.; Sheng, J.; Mortimer, P.E. Discovery of Novel Fungal Species and Pathogens on Bat Carcasses in a Cave in Yunnan Province, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1554–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, R.; Kurczaba, K.; Cal, M.; Apoznański, G.; Kokurewicz, T. A Culture-Based ID of Micromycetes on the Wing Membranes of Greater Mouse-Eared Bats (Myotis myotis) from the “Nietoperek” Site (Poland). Animals 2020, 10, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyske, Z.; Jaroszewicz, W.; Żabińska, M.; Lorenc, P.; Sochocka, M.; Bielańska, P.; Węgrzyn, G. Unexplored Potential: Biologically Active Compounds Produced by Microorganisms from Hard-to-Reach Environments and Their Applications. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2021, 68, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelet, M. Micromyètes du Var et d’Ailleurs (2me Note). Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Archéol. Toulon Var 1969, 21, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval-Denis, M.; Guarro, J.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Sutton, D.A.; Wiederhold, N.P.; de Hoog, G.S.; Gené, J. Phylogeny and Taxonomic Revision of Microascaceae with Emphasis on Synnematous Fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2016, 83, 193–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M.B. More Dematiaceous Hyphomycetes; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: London, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Gams, W. Two New Species of Wardomyces. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1968, 51, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W.; Anderson, T.H. Compendium of Soil Fungi, 2nd ed.; IHW Verlag: Eching, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.-M.; Yang, S.-Y.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Ma, H.-H.; Tu, Y.-H.; Li, W.; Cai, L. Microascaceae from the Marine Environment, with Descriptions of Six New Species. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet-Rossinni, A.K.; Wilkinson, G.S. Methods for age estimation and the study of senescence in bats. In Ecological and Behavioral Methods for the Study of Bats; Kunz, T.H., Parsons, S., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2009; pp. 315–325. [Google Scholar]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.J.W.T.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid Genetic Identification and Mapping of Enzymatically Amplified Ribosomal DNA from Several Cryptococcus Species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, G.H.; Spatafora, J.W.; Zare, R.; Hodge, K.T.; Gams, W. A Revision of Verticillium sect. Prostrata. II. Phylogenetic Analyses of SSU and LSU Nuclear rDNA Sequences from Anamorphs and Teleomorphs of the Clavicipitaceae. Nova Hedwig. 2001, 72, 311–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Buckley, E. A Beauveria Phylogeny Inferred from Nuclear ITS and EF1-α Sequences: Evidence for Cryptic Diversification and Links to Cordyceps Teleomorphs. Mycologia 2005, 97, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Burgess, T.I.; Carnegie, A.J.; Hardy, G.; Smith, D.; Summerell, B.A.; Cano-Lira, J.F.; Guarro, J.; Houbraken, J.; et al. Fungal Planet Description Sheets: 625–715. Persoonia 2017, 39, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malloch, D. Wardomyces aggregatus sp. nov. and Its Possible Relationship to Gymnodochium fimicolum. Can. J. Bot. 1970, 48, 883–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennebert, G.L. Echinobotryum, Wardomyces and Mammaria. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1968, 51, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, J.; Kawasaki, Y.; Kurata, H. Wardomyces simplex (Hyphomycetes) and Its Annellospores. Bot. Mag. Tokyo 1969, 82, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, N.J.; Webster, J. Fungi of Extreme Environments. In Fungal Ecology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 322–340. [Google Scholar]

- Stupar, M.; Savković, Ž.; Pećić, M.; Jerinkić, D.; Jakovljević, O.; Popović, S. Some Like It Rock ’N’ Cold: Speleomycology of Ravništarka Cave (Serbia). J. Fungi 2025, 11, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.R.; Cai, L.; Liu, F. Oligotrophic Fungi from a Carbonate Cave, with Three New Species of Cephalotrichum. Mycology 2017, 8, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzęcka, J.; Piecuch, A.; Kokurewicz, T.; Lavoie, K.H.; Ogórek, R. Greater mouse-eared bats (Myotis myotis) hibernating in the Nietoperek Bat Reserve (Poland) as a vector of airborne culturable fungi. Biology 2021, 10, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, P.; van den Eynde, C.; Baert, F.; D’hooge, E.; De Pauw, R.; Normand, A.C.; Piarroux, R.; Stubbe, D. Remarkable fungal biodiversity on northern Belgium bats and hibernacula. Mycologia 2023, 115, 484–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X. Asian bat skin mycobiome maintains defense against Pseudogymnoascus destructans during hibernation. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e00611-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, L.; Masulli, M.; De Laurenzi, V.; Allocati, N. An overview of bats microbiota and its implication in transmissible diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1012189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain/Isolate | GenBank Accession Number | Isolation Source | Country (geo_loc_name) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSU | ITS | TEF1α | |||

| Cephalotrichum asperulum CBS 582.71 | LN851007 | LN850960 | KX924043 | Soil | Argentina: Buenos Aires |

| C. purpureofuscum CBS 157.57 | LN851031 | LN850984 | LN851084 | Tuber | The Netherlands: Wageningen |

| C. cylindricum UAMH 1348 | LN851012 | LN850965 | LN851066 | Seed of sorghum | USA: Kansas |

| C. dendrocephalum CBS 528.85 | LN851013 | LN850966 | LN851067 | Cultivated soil | Iraq: Basrah |

| C. gorgonifer UAMH 3585 | LN851025 | LN850978 | LN851078 | Mushroom compost | Canada: Alberta |

| C. guizhouense CGMCC 3.18330 | MF419758 | MF419788 | MF419728 | Air from cave | China: Guizhou |

| C. stemonitis CBS 289.66 | LN851032 | LN850985 | LN851085 | Dung of deer | Australia: Tasmania |

| C. leave CGMCC 3.18329 | MF419778 | MF419808 | MF419748 | Limestone from cave | China: Guizhou |

| C. purpureofuscum CBS 523.63 | LN851014 | LN850967 | LN851068 | Wheat field soil | Germany: Schleswig-Holstein |

| C. nanum CBS 191.61 | LN851016 | LN850969 | LN851070 | Dung of deer | England: Surrey |

| C. oligotriphicum CGMCC 3.18328 | MF419771 | MF419801 | MF419741 | Limestone from cave | China: Guizhou |

| C. purpureofuscum UAMH 9209 | LN851018 | LN850971 | LN851072 | Indoor air | Canada: British Columbia, |

| C. purpureofuscum WL06350 | OR339942 | OR339896 | OR347707 | Sargassum confusum | China: Shenzhen, Guangdong |

| C. stemonitis CBS 103.19 | LN850952 | LN850951 | LN850953 | Seed | Netherlands: Wageningen |

| Gamsia aggregata CBS 251.69 | LM652500 | LM652378 | - | Dung of carnivore | USA |

| G. batmanii * | PX589482 | PX589483 | PX667539 | Miniopterus schreibersii | Serbia: Sesalačka cave |

| G. columbina CBS 233.66 | LN851039 | LN850990 | LN851092 | Sandy soil | Germany: Giesen |

| G. columbina CBS 235.66 | - | MH858785 | - | Wheat field soil | Germany: Schleswig-Holstein |

| G. kooimaniorum CBS 143185 | - | NR_159824 | - | Garden soil | The Netherlands |

| G. sedimenticola WL02722 | OR339947 | OR339900 | OR347712 | Intertidal sediment | China: Qingdao, Shandong |

| G. sedimenticola WL06358 | OR339948 | OR339901 | OR347713 | Intertidal sediment | China: Qingdao, Shandong |

| G. sedimenticola WL06359 | OR339949 | OR339902 | OR347714 | Intertidal sediment | China: Qingdao, Shandong |

| G. simplex CBS 546.69 | LM652501 | LM652379 | LN851094 | Milled Oryza sativa | Japan |

| Gamsia sp. NWHC 44767-31 1LNA | - | MK793938 | - | East bats? | USA: Madison |

| Graphium penicillioides CBS 102632 | KY852485 | KY852474 | - | Populus nigra | Czech Republic |

| Kernia columnaris CBS 159.66 | LN851010 | LN850963 | LN851064 | Dung of hair | South Africa: Johannesburg |

| Parawardomyces giganteus CBS 746.69 | MH871180 | MH859408 | LN851096 | Insect frass in dead log | Canada: Ontario |

| P. ovalis CBS 234.66 | LN851050 | MH858784 | LN851101 | Wheat field soil | Germany: Schleswig-Holstein |

| Pseudowardomyces pulvinatus CBS 112.65 | MH870142 | MH858508 | LN851102 | Salt marsh | England: Cheshire |

| Wardomyces anomalus CBS 299.61 | MH869626 | MH858058 | LN851095 | Air cell of egg | Canada: Ontario |

| W. inflatus CBS 216.61 | LM652553 | LM652496 | LN851098 | Wood, Acer sp. | Canada: Quebec |

| W. inflatus WL02318 | OR339982 | OR339937 | OR347750 | Intertidal sediment | China: Huludao, Liaoning |

| Wardomycopsis dolichi LC12503 | MK329043 | MK329138 | MK336073 | Soil | China: Guilin, Guangxi |

| Wa. fusca LC12476 | MK329047 | MK329142 | MK336077 | Soil | China: Guilin, Guangxi |

| Wa. fumicola CBS 487.66 | LM652554 | LM652497 | - | Soil | Canada: Ontario |

| Wa. inopinata FMR 10305 | LM652555 | LM652498 | - | Soil | India |

| Wa. litoralis CBS 119740 | LN851055 | LN851000 | LN851107 | Beach soil | Spain: Castellon |

| Wa. longicatenata CGMCC 3.17947 | KU746756 | KU746710 | KX855255 | Air | China: Guizhou |

| Species | Conidiophores | Blastic Conidia | Annelidic Conidia | Isolation Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

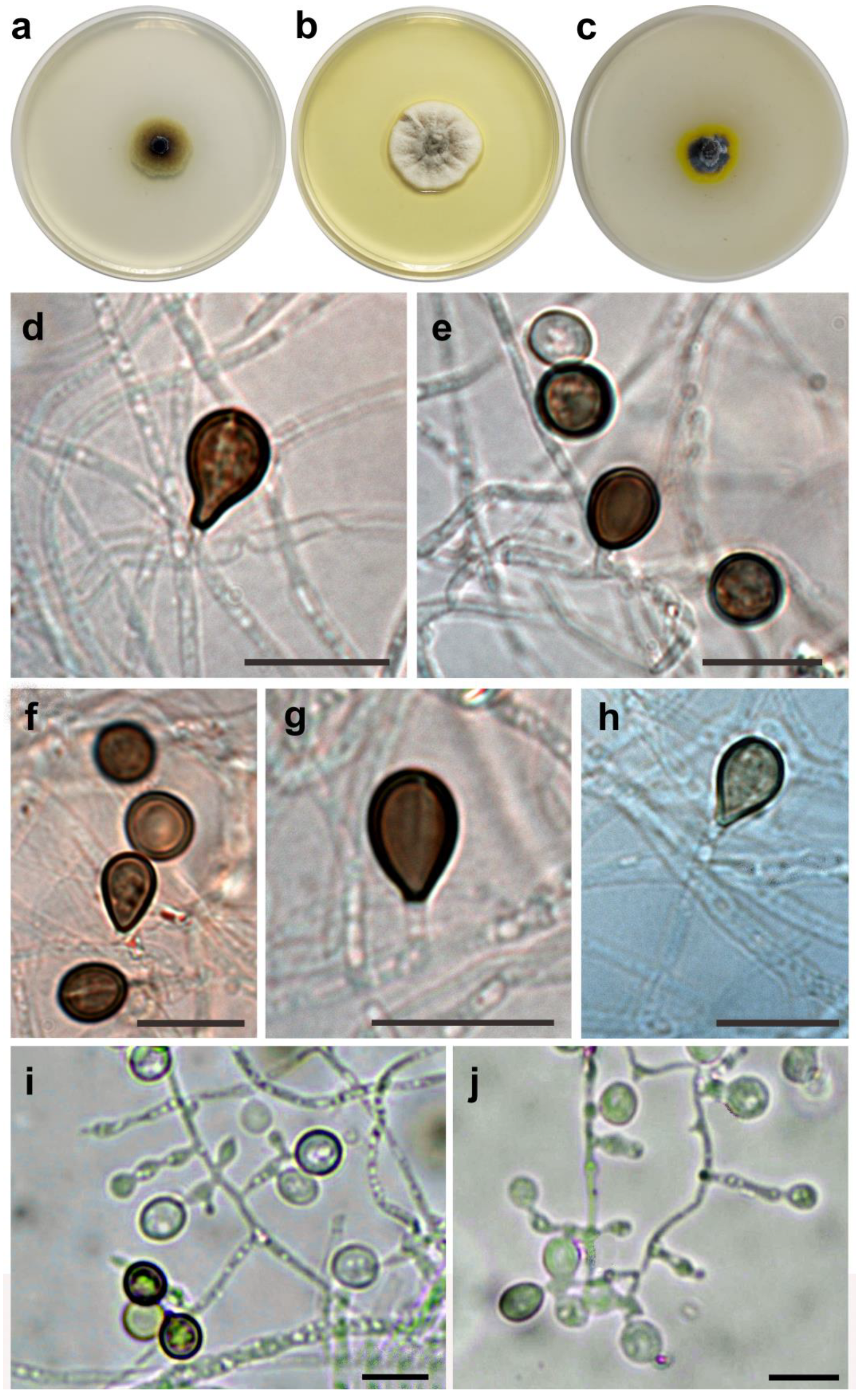

| Gamsia batmanii | Short or reduced to conidiogenous cells, polyblastic; annelides solitary. | Subglobose, obovoid to pyriform, with rounded apex (5.9–8.8 × 5.5–6.5 μm) | Aseptate, subglobose to obovoid, with rounded apex (6.5–7.9 × 5.3–6.0 μm) | Bat skin, Sesalačka cave, Serbia | This study |

| Gamsia aggregata | Polyblastic conidiogenous cells on short conidiophores; annelides solitary or grouped in sporodochia | Broadly ellipsoidal to ovoid, with rounded apex (4–7.5 × 3.5–5 μm) | 2-celled, ellipsoidal (8–10.5 × 3.5–5 μm) | Dung of carnivore, Wycamp Lake, Michigan | Malloch [26] |

| Gamsia kooimanorum | Mostly undifferentiated, unbranched or rarely laterally branched once, with polyblastic conidiogenous cells; annelides unbranched, rarely branched one or two times from a short, cylindrical and swollen basal cell, mostly grouped in dense sporodochia | Ovoid to broadly ellipsoidal, with rounded to pointed apex (7–9 × 5–6.5 mm) | Aseptate, oval, ellipsoidal to bullet-shaped, apex rounded (7.5–8.5 × 4.5–5.5 μm) | Garden soil, Vleuten, The Netherlands | Crous et al. [25] |

| Gamsia columbina | Polyblastic conidiogenous cells on short conidiophores; annellides solitary or grouped in sporodochia | Oval to ellipsoidal, with slightly pointed apex (6–13 × 3.5–6.5 μm) | 1–2-celled, oval (5–10.5 × 2.5–5.5 μm) | Air, soil and decaying wood, Austria, Germany, Japan, The Netherlands | Sandoval-Denis et al. [15] |

| Gamsia sedimenticola | Reduced to conidiogenous cells, with 1–3 apical conidiogenous loci | Ovoid, with rounded to pointed apex (7–9 × 5–6.5 μm) | Broadly ellipsoidal, 0–1-septate | Intertidal sediment of a mudflat, Qingdao city, China | Wang et al. [19] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Savković, Ž.; Burazerović, J.; Jovanović, M.; Arsenijević, S.; Stupar, M. Gamsia batmanii sp. nov. Isolated from a Common Bent-Wing Bat and the Review of the Genus Gamsia. Microbiol. Res. 2026, 17, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010009

Savković Ž, Burazerović J, Jovanović M, Arsenijević S, Stupar M. Gamsia batmanii sp. nov. Isolated from a Common Bent-Wing Bat and the Review of the Genus Gamsia. Microbiology Research. 2026; 17(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSavković, Žejko, Jelena Burazerović, Marija Jovanović, Sara Arsenijević, and Miloš Stupar. 2026. "Gamsia batmanii sp. nov. Isolated from a Common Bent-Wing Bat and the Review of the Genus Gamsia" Microbiology Research 17, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010009

APA StyleSavković, Ž., Burazerović, J., Jovanović, M., Arsenijević, S., & Stupar, M. (2026). Gamsia batmanii sp. nov. Isolated from a Common Bent-Wing Bat and the Review of the Genus Gamsia. Microbiology Research, 17(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010009