Identification and Characterization of a Proteinaceous Antibacterial Factor from Pseudomonas extremorientalis PEY1 Active Against Edwardsiella tarda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Identification of the Antibacterial Strain

2.2. Optimization of Culture Conditions and Antibacterial Activity Assay

2.2.1. Effect of Aeration and Temperature

2.2.2. Effect of Carbon and Nitrogen Sources

2.2.3. Effect of Initial pH

2.2.4. Growth Kinetics

2.2.5. Antibacterial Activity Assay

2.3. Characterization of Antibacterial Substances Produced by P. extremorientalis PEY1

2.3.1. Preparation of Cell-Free Supernatant

2.3.2. Thermal and pH Stability

2.3.3. Chemical Stability

2.3.4. Metal Ion Sensitivity

2.3.5. Proteolytic Enzyme Sensitivity

2.4. Identification of the Antibacterial Substance

2.4.1. SDS-PAGE Analysis and Protease/Heat Sensitivity

2.4.2. LC–MS/MS Protein Identification

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of Culture Conditions and Evaluation of Antibacterial Activity

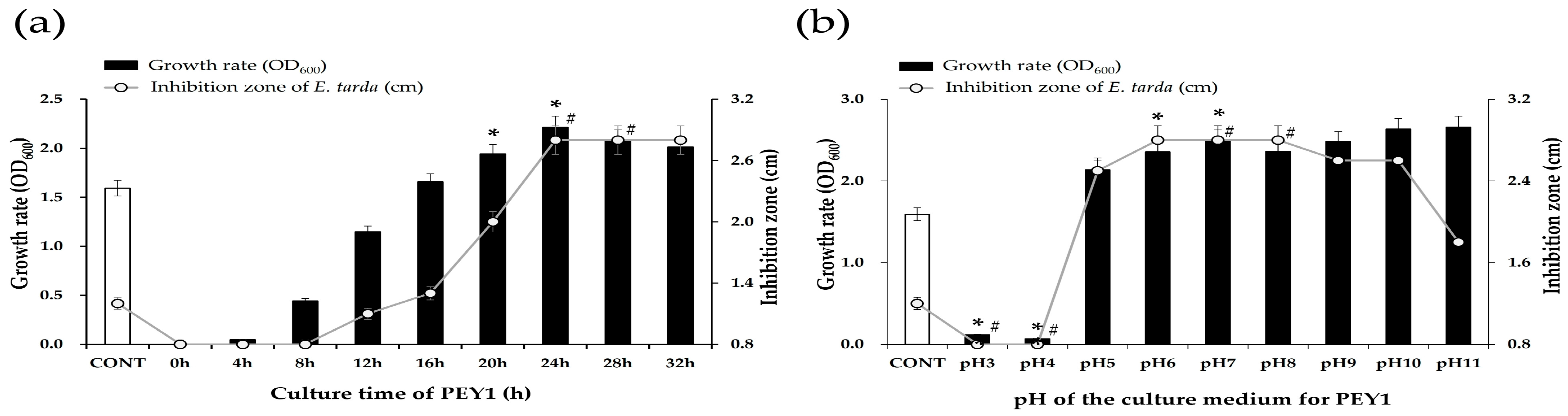

3.2. Characterization of Growth and Antibacterial Activity

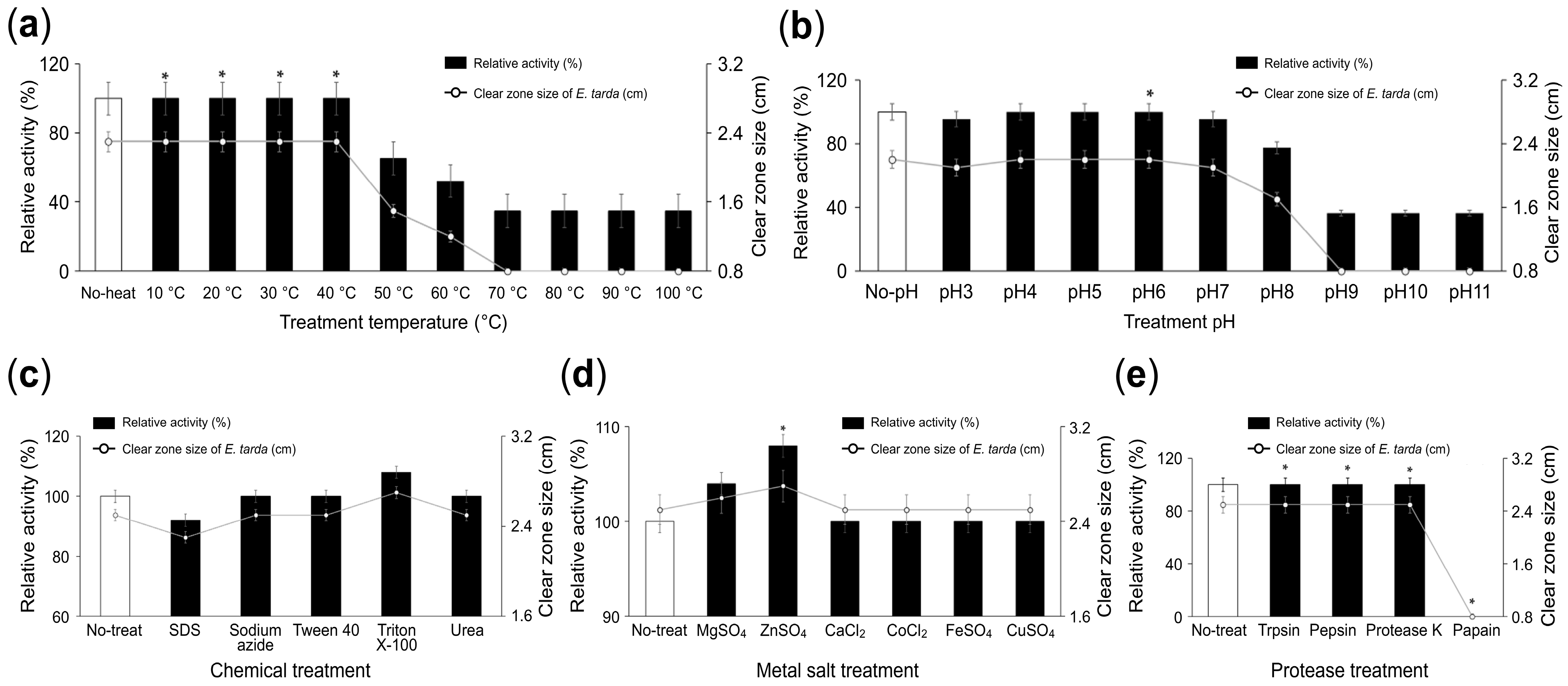

3.3. Physicochemical Properties

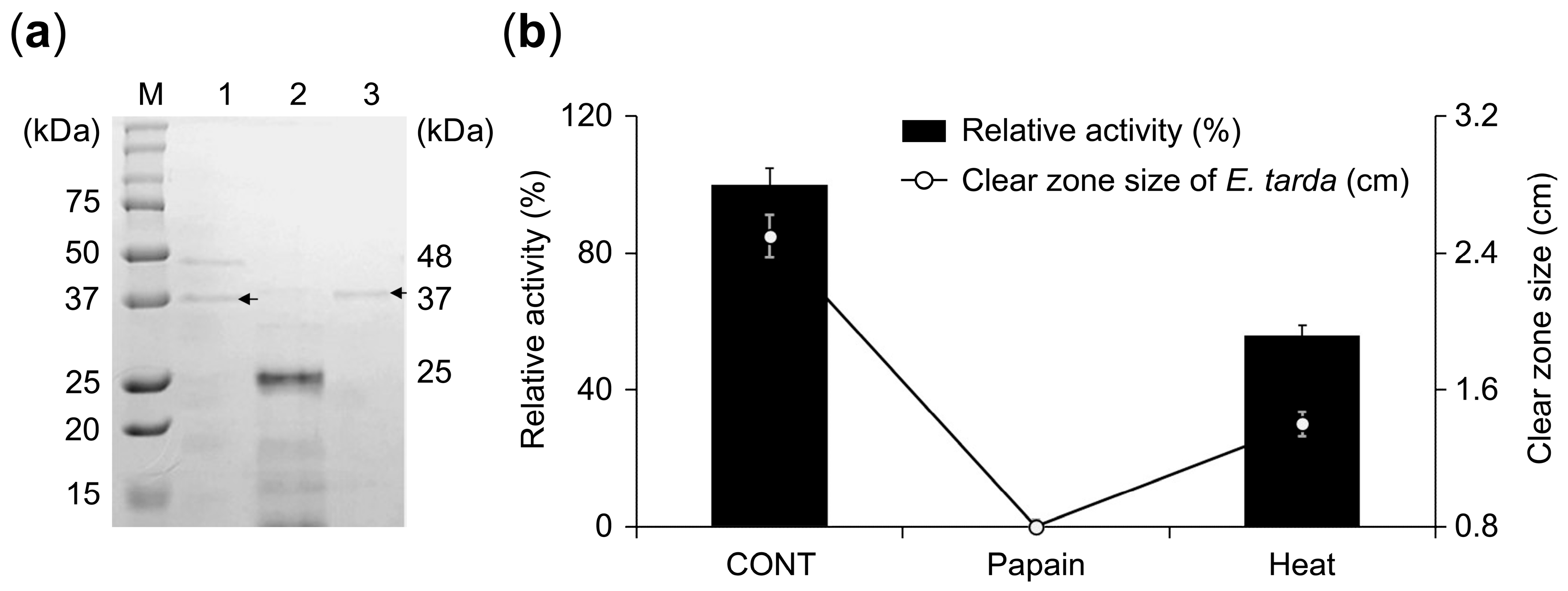

3.4. Identification and Characterization of the Antibacterial Protein

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Austin, B.; Austin, D.A. Bacterial Fish Pathogens: Disease of Farmed and Wild Fish, 6th ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.B.; Aoki, T.; Jung, T.S. Pathogenesis of and strategies for preventing Edwardsiella tarda infection in fish. Vet. Res. 2012, 43, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondad-Reantaso, M.G.; Subasinghe, R.P.; Arthur, J.R.; Ogawa, K.; Chinabut, S.; Adlard, R.; Tan, Z.; Shariff, M. Disease and health management in Asian aquaculture. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 132, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, F.C. Heavy use of prophylactic antibiotics in aquaculture: A growing problem for human and animal health and for the environment. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 8, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, J.E.M.; Schreier, H.J.; Lanska, L.; Hale, M.S. The rising tide of antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: Sources, sinks and solutions. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Defoirdt, T.; Sorgeloos, P.; Bossier, P. Alternatives to antibiotics for the control of bacterial disease in aquaculture. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, A. Progress, challenges and opportunities in fish vaccine development. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 90, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munang’andu, H.M.; Evensen, Ø. A review of intra- and extracellular antigen delivery systems for virus vaccines of finfish. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 960859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Ross, R.P. Bacteriocins: Developing innate immunity for food. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Sieiro, P.; Montalbán-López, M.; Mu, D.; Kuipers, O.P. Bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria: Extending the family. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2939–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.C.; Lin, C.H.; Sung, C.T.; Fang, J.Y. Antibacterial activities of bacteriocins: Application in foods and pharmaceuticals. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.H.; Zendo, T.; Sonomoto, K. Novel bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria (LAB): Various structures and applications. Microb. Cell Fact. 2014, 13, S3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Man, J.C.; Rogosa, M.; Sharpe, M.E. A medium for the cultivation of Lactobacilli. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1960, 23, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouiri, M.; Sadiki, M.; Ibnsouda, S.K. Methods for in vitro evaluating antimicrobial activity: A review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2016, 6, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Gorshkova, N.M.; Sawabe, T.; Hayashi, K.; Kalinovskaya, N.I.; Lysenko, A.M.; Zhukova, N.V.; Nicolau, D.V.; Kuznetsova, T.A.; Mikhailov, V.V.; et al. Pseudomonas extremorientalis sp. nov., isolated from a drinking water reservoir. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 2113–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, D.M. Pseudomonas biocontrol agents of soilborne pathogens: Looking back over 30 years. Phytopathology 2007, 97, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, C.; Perrin, E.; Poli, A.; Finore, I.; Fani, R.; Lo Giudice, A. Characterization of the exopolymer-producing Pseudoalteromonas sp. S8-8 from Antarctic sediment. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 7173–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Wilm, M.; Vorm, O.; Mann, M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996, 68, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scigelova, M.; Makarov, A. Orbitrap mass analyzer—Overview and applications in proteomics. Proteomics 2006, 6, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, H.; Loper, J.E. Genomics of secondary metabolite production by Pseudomonas spp. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 1408–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lu, C.D. Regulation of carbon and nitrogen utilization by CbrAB and NtrBC two-component systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 5413–5420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, A.; Alhanout, K.; Duval, R.E. Bacteriocins, antimicrobial peptides from bacterial origin: Overview of their biology and their impact against multidrug-resistant bacteria. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parret, A.H.; Temmerman, K.; De Mot, R. Novel lectin-like bacteriocins of biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5197–5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghequire, M.G.K.; Öztürk, B.; De Mot, R. Lectin-like bacteriocins. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jeon, H.; Han, H.S.; Hur, J.W. Evaluation of Bacillus albus SMG-1 and B. safensis SMG-2 isolated from Saemangeum Lake as probiotics for aquaculture of white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Aquac. Rep. 2021, 21, 100743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łasica, A.M.; Jagusztyn-Krynicka, E.K. The role of Dsb proteins of Gram-negative bacteria in the process of pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 31, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaked, H.P.S.; Cao, L.; Biswas, I. Redox sensing modulates the activity of the ComE response regulator of Streptococcus mutans. J. Bacteriol. 2021, 203, e0033021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shouldice, S.R.; Heras, B.; Jarrott, R.; Sharma, P.; Scanlon, M.J.; Martin, J.L. Characterization of the DsbA oxidative folding catalyst from Pseudomonas aeruginosa reveals a highly oxidizing protein that binds small molecules. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Shi, M.; Tu, F.; Yu, A.; Li, M.; Yang, M. Two DsbA proteins are important for Vibrio parahaemolyticus pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, S.; Mao, J. Impact of bacteriocins on multidrug-resistant bacteria and their application in aquaculture disease prevention and control. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1048–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzoza, P.; Godlewska, U.; Borek, A.; Morytko, A.; Zegar, A.; Kwiecinska, P.; Zabel, B.A.; Osyczka, A.; Kwitniewski, M.; Cichy, J. Redox active antimicrobial peptides in controlling growth of microorganisms at body barriers. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Accession No. | Species | Coverage (%) | Peptides (>95%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| protein disulfide reductase | WP_123474076.1 | Pseudomonas | 40.2 | 16 |

| alkaline phosphatase | WP_060613926.1 | Pseudomonas | 37.9 | 7 |

| elongation factor Tu | WP_020290706.1 | Pseudomonas | 9.8 | 1 |

| FAD-dependent oxidoreductase | WP_105228981.1 | Pseudomonas | 6 | 1 |

| pyridoxal kinase PdxY | WP_065879229.1 | Pseudomonas | 8.3 | 1 |

| hypothetical protein | WP_041924669.1 | Pseudomonas | 18.1 | 1 |

| 1-deoxy-D-xylulose-5-phosphate reductoisomerase | WP_069863658.1 | Pseudomonas | 7.8 | 1 |

| sulfurtransferase complex subunit TusB | WP_069517293.1 | Pseudomonas | 21.2 | 1 |

| phasin family protein | WP_109752025.1 | Pseudomonas | 38.1 | 1 |

| SDR family oxidoreductase | WP_029886093.1 | Pseudomonas | 7.6 | 1 |

| thioredoxin | WP_081319933.1 | Pseudomonas | 3.1 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jo, H.-S.; Jo, Y.-L.; Hong, S.-M. Identification and Characterization of a Proteinaceous Antibacterial Factor from Pseudomonas extremorientalis PEY1 Active Against Edwardsiella tarda. Microbiol. Res. 2026, 17, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010006

Jo H-S, Jo Y-L, Hong S-M. Identification and Characterization of a Proteinaceous Antibacterial Factor from Pseudomonas extremorientalis PEY1 Active Against Edwardsiella tarda. Microbiology Research. 2026; 17(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleJo, Hyun-Sol, Youl-Lae Jo, and Sun-Mee Hong. 2026. "Identification and Characterization of a Proteinaceous Antibacterial Factor from Pseudomonas extremorientalis PEY1 Active Against Edwardsiella tarda" Microbiology Research 17, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010006

APA StyleJo, H.-S., Jo, Y.-L., & Hong, S.-M. (2026). Identification and Characterization of a Proteinaceous Antibacterial Factor from Pseudomonas extremorientalis PEY1 Active Against Edwardsiella tarda. Microbiology Research, 17(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010006