Ureaplasma Species and Human Papillomavirus Coinfection and Associated Factors Among South African Adolescent Girls and Young Women

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of U. urealyticum and U. parvum by Age Group Among AGYW

3.2. Factors Associated with U. urealyticum and U. parvum

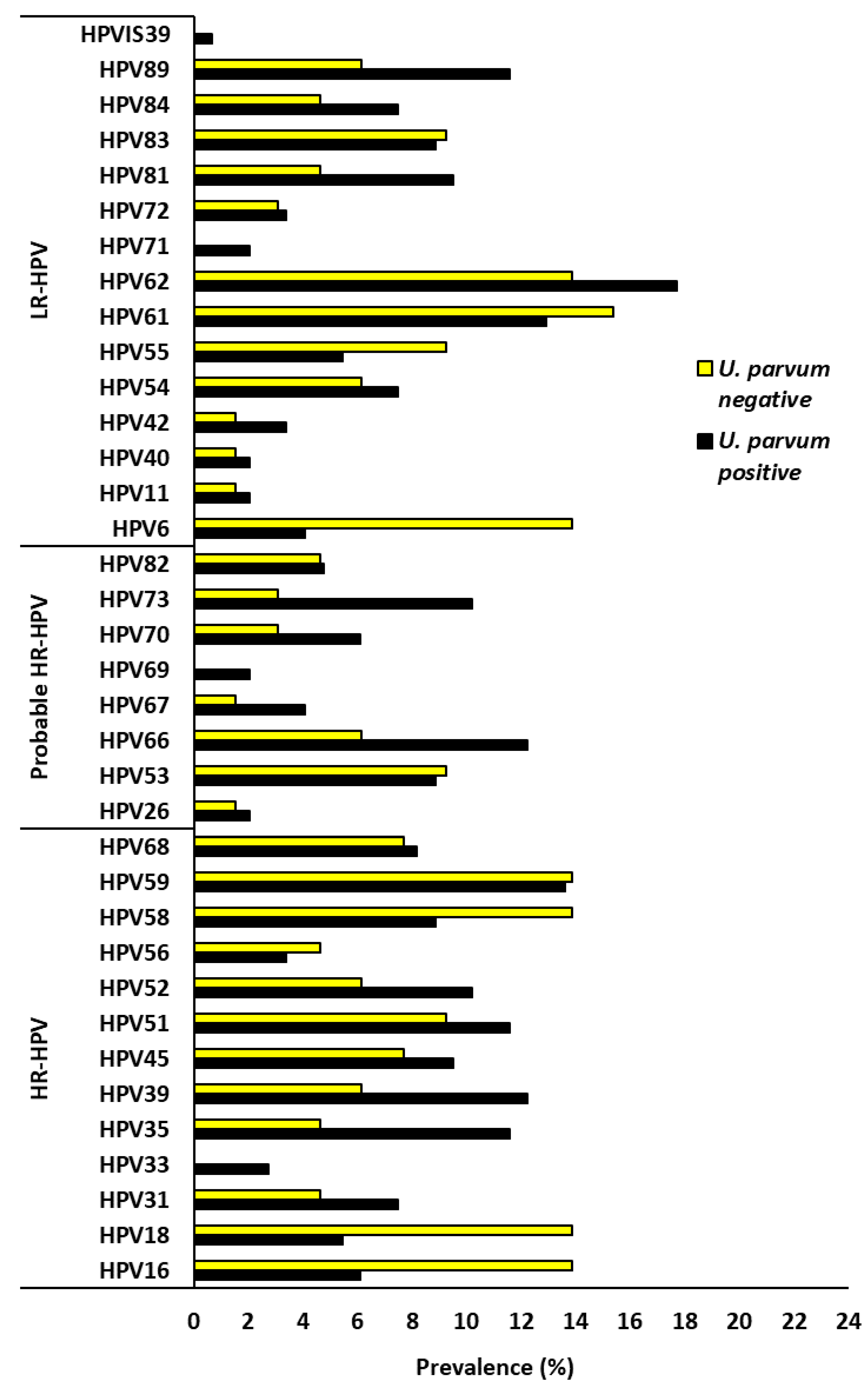

3.3. U. urealyticum, U. parvum, and HPV Co-Infection Among AGYW

3.4. Impact of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum on HPV Types Targeted by Current HPV Vaccines

3.5. Factors Associated with Ureaplasma urealyticum and HPV Co-Infection Among AGYW

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGYW | Adolescent Girls and Young Women |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| HPV | Human Papillomavirus |

| HR | High Risk |

| HSV | Herpes Simplex Virus |

| LR | Low Risk |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PR | Prevalence Ratio |

| STI | Sexually Transmitted Infection |

| UP | Ureaplasma parvum |

| UU | Ureaplasma urealyticum |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Dawood, A.; Algharib, S.A.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, T.; Qi, M.; Delai, K.; Hao, Z.; Marawan, M.A.; Shirani, I.; Guo, A. Mycoplasmas as host pantropic and specific pathogens: Clinical implications, gene transfer, virulence factors, and future perspectives. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 855731. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Huerta, M.; Barberá, M.J.; Serra-Pladevall, J.; Esperalba, J.; Martínez-Gómez, X.; Centeno, C.; Pich, O.Q.; Pumarola, T.; Espasa, M. Mycoplasma genitalium and antimicrobial resistance in Europe: A comprehensive review. Int. J. STD AIDS 2020, 31, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobão, T.N.; Campos, G.; Selis, N.; Amorim, A.T.; Souza, S.; Mafra, S.; Pereira, L.; Dos Santos, D.; Figueiredo, T.; Marques, L. Ureaplasma urealyticum and U. parvum in sexually active women attending public health clinics in Brazil. Epidemiol. Infect. 2017, 145, 2341–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silwedel, C.; Laube, M.; Speer, C.P.; Glaser, K. The role of Ureaplasma species in prenatal and postnatal morbidity of Preterm infants: Current concepts. Neonatology 2024, 121, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukavhanyedzi, D.; Rukasha, I. Sexually transmitted pathogens in asymptomatic women at Rethabile clinic, Limpopo, South Africa. South. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 39, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zidi, S.; Almawi, W.Y.; Abassi, S. Genital mycoplasma infections: A hidden factor in cervical cancer progression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, M.S.; Silva, M.C.A.T.d.; Brito, M.B.; Gonçalves, A.K. Clinical and uterine cervix characteristics of women with Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma in genital discharge. Rev. Da Assoc. Médica Bras. 2024, 70, e20240045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutoiu, A.; Boda, D. Prevalence of Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis and Chlamydia trachomatis in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Biomed. Rep. 2023, 19, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liao, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, W.; Deng, Y.; Liu, C. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Ureaplasma urealyticum infections in males and females of childbearing age in Chengdu, China. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1566163. [Google Scholar]

- Taku, O.; Brink, A.; Meiring, T.L.; Phohlo, K.; Businge, C.B.; Mbulawa, Z.Z.; Williamson, A.-L. Detection of sexually transmitted pathogens and co-infection with human papillomavirus in women residing in rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onywera, H.; Mabunda, S.A.; Williamson, A.-L.; Mbulawa, Z.Z. Microbiological and behavioral determinants of genital HPV infections among adolescent girls and young women warrant the need for targeted policy interventions to reduce HPV risk. Front. Reprod. Health 2022, 4, 887736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruni, L.; Albero, G.; Serrano, B.; Mena, M.; Collado, J.J.; Gómez, D.; Muñoz, J.; Bosch, F.; de Sanjosé, S. ICO/IARC Information Centre on HPV and Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Human Papillomavirus and Related Diseases in South Africa. Summ. Rep. 2023. Available online: https://hpvcentre.net/statistics/reports/ZAF.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Delany-Moretlwe, S.; Kelley, K.F.; James, S.; Scorgie, F.; Subedar, H.; Dlamini, N.R.; Pillay, Y.; Naidoo, N.; Chikandiwa, A.; Rees, H. Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction in South Africa: Implementation lessons from an evaluation of the national school-based vaccination campaign. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2018, 6, 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botha, M.; Mabenge, M.; Makua, M.; Mbodi, M.; Rogers, L.; Sebitloane, M.; Smith, T.; Van der Merwe, F.; Williamson, A.; Whittaker, J. Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines for South Africa. Afr. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2023, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Noma, I.H.Y.; Shinobu-Mesquita, C.S.; Suehiro, T.T.; Morelli, F.; De Souza, M.V.F.; Damke, E.; Da Silva, V.R.S.; Consolaro, M.E.L. Association of Righ-Risk Human Papillomavirus and Ureaplasma parvum Co-Infections with Increased Risk of Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Cervical Lesions. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021, 22, 1239–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardhia, M.; Yasmon, A.; Indarti, J.; Rachmadi, L. Role of Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum as Risk Factors for Cervical Dysplasia with Human Papillomavirus. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Song, T.; Zeng, X.; Li, L.; Hou, M.; Xi, M. Association between genital mycoplasmas infection and human papillomavirus infection, abnormal cervical cytopathology, and cervical cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulawa, Z.Z.A.; Somdyala, N.I.; Mabunda, S.A.; Williamson, A.-L. High human papillomavirus prevalence among females attending high school in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urszula, K.; Joanna, E.; Marek, E.; Beata, M.; Magdalena, S.B. Colonization of the lower urogenital tract with Ureaplasma parvum can cause asymptomatic infection of the upper reproductive system in women: A preliminary study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2014, 289, 1129–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, C.; Tootla, H.; Amien, I.; Engel, M.E. Evaluating the utility of the Allplex STI Essential Assay to determine the occurrence of urogenital sexually transmitted infections among symptomatic and asymptomatic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprong, K.E.; Mabenge, M.; Wright, C.A.; Govender, S. Ureaplasma species and preterm birth: Current perspectives. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 46, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rak, K.; Kiecka, A.; Białecka, J.; Kawalec, A.; Krzyściak, P.; Białecka, A. Retrospective analysis of the ureaplasma spp. Prevalence with reference to other genital tract infections in women of reproductive age. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2022, 71, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Jin, H.; Lee, K.E. Prevalence of sexually transmitted pathogen coinfections in high risk-human papillomaviruses infected women in Busan. Biomed. Sci. Lett. 2019, 25, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Yang, T.; Kong, Y.; Xie, X.; Ruan, Z. Ureaplasma infections: Update on epidemiology, antimicrobial resistance, and pathogenesis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 51, 317–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, O.S.; Letafati, A.; Dehkordi, S.E.; Farahani, A.V.; Bahari, M.; Mahdavi, B.; Ariamand, N.; Taghvaei, M.; Kohkalani, M.; Pirkooh, A.A. From infection to infertility: A review of the role of human papillomavirus-induced oxidative stress on reproductive health and infertility. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gregorio, A.; Aranda-Rivera, A.K.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Human papillomavirus-related cancers and mitochondria. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhokotera, T.; Asangbeh, S.; Bohlius, J.; Singh, E.; Egger, M.; Rohner, E.; Ncayiyana, J.; Clifford, G.M.; Olago, V.; Sengayi-Muchengeti, M. Cervical cancer in women living in South Africa: A record linkage study of the National Health Laboratory Service and the National Cancer Registry. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Zhao, H.; Di, J.; Lin, G.; Lin, Y.; Lin, X.; Zheng, M. Association of human papillomavirus infection with other microbial pathogens in gynecology. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2010, 45, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Ge, Y.; Shi, N.; Guo, C.; Ruan, J.; Alalawy, A.I.; Yao, L.; Liu, G.; Liu, B.; 30. Insight into the Complex Interaction between Vaginal Microbiome, Metabolome, and Host Gene Expression in Cervical Cancer Progression. Metabolome Host Gene Expr. Cerv. Cancer Progress 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; MacIntyre, D.A.; Lee, Y.S.; Smith, A.; Marchesi, J.R.; Lehne, B.; Bhatia, R.; Lyons, D.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Li, J.V.; et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia disease progression is associated with increased vaginal microbiome diversity. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, J.; Himal, I.; Kannan, S. Role of microbial dysbiosis in carcinogenesis & cancer therapies. Indian J. Med. Res. 2020, 152, 553–561. [Google Scholar]

- Kyrgiou, M.; Mitra, A.; Moscicki, A.-B. Does the vaginal microbiota play a role in the development of cervical cancer? Transl. Res. 2017, 179, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, M.A.E.; Morad, A.W.A.; Azzazi, A.; Fayed, S.M.; Eldin, A.K.Z. Association between genital mycoplasma and cervical squamous cell atypia. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2013, 18, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abavisani, M.; Keikha, M. Global analysis on the mutations associated with multidrug-resistant urogenital mycoplasmas and ureaplasmas infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2023, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total | U. urealyticum | PR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | % | |||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 15–17 years | 43 | 12 | 27.9 | Reference | |

| 18–19 years | 115 | 54 | 47.0 | 1.68 (1.00–2.83) | 0.046 |

| 20–23 years | 56 | 28 | 50.0 | 1.79 (1.04–3.10) | 0.038 |

| Ever smoke | |||||

| No | 177 | 81 | 45.8 | Reference | |

| Yes | 37 | 13 | 35.1 | 0.77 (0.47–1.17) | 0.277 |

| Sexual debut, years | |||||

| ≤15 years | 85 | 41 | 48.2 | Reference | |

| 16–17 years | 129 | 52 | 40.3 | 0.84 (0.61–1.13) | 0.263 |

| Number of lifetime sexual partnersΣ | |||||

| 1 | 50 | 15 | 30.0 | Reference | |

| 2–3 | 117 | 58 | 49.6 | 1.65 (1.08–2.68) | 0.026 |

| 4–6 | 34 | 18 | 52.9 | 1.77 (1.04–3.00) | 0.043 |

| Number of new sexual partners past 3 monthsΣ | |||||

| 0 | 33 | 9 | 27.3 | Reference | |

| 1 | 142 | 70 | 49.3 | 1.81 (1.01–3.23) | 0.032 |

| 2–4 | 26 | 12 | 46.2 | 1.69 (0.84–3.39) | 0.174 |

| Frequency of vaginal sexual intercourse past 1 month ∑ | |||||

| 0 | 44 | 15 | 34.1 | Reference | |

| 1 | 55 | 24 | 43.6 | 1.28 (0.77–2.13) | 0.409 |

| 2–3 | 78 | 38 | 48.7 | 1.43 (0.89–2.29) | 0.132 |

| 4–10 | 26 | 14 | 53.8 | 1.58 (0.92–2.72) | 0.135 |

| Ever consumed alcohol Σ | |||||

| No | 39 | 13 | 33.3 | Reference | |

| Yes | 175 | 81 | 46.3 | 1.39 (0.91–2.30) | 0.157 |

| Drunk during last sexual intercourseΣ | |||||

| No | 189 | 85 | 45.0 | Reference | |

| Yes | 12 | 6 | 50.0 | 1.11 (0.62–2.00) | 0.772 |

| Ever pregnant Σ | |||||

| No | 167 | 70 | 41.9 | Reference | |

| Yes | 47 | 24 | 51.1 | 1.22 (0.85–1.66) | 0.319 |

| Currently on contraception Σ | |||||

| No | 64 | 26 | 40.6 | Reference | |

| Yes | 136 | 65 | 47.8 | 1.18 (0.83–1.66) | 0.365 |

| Condom use during last intercourse Σ | |||||

| No | 124 | 59 | 47.6 | Reference | |

| Yes | 77 | 32 | 41.6 | 0.87 (0.63–1.21) | 0.467 |

| U. urealyticum | U. parvum | U. urealyticum or parvum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive % (n/93) | Negative % (n/119) | p-Value | Positive % (n/147) | Negative % (n/65) | p-Value | Positive % (n/183) | Negative % (n/29) | p-Value | |

| HPV infection | 82.8 (77) | 70.6 (84) | 0.052 | 78.9 (116) | 69.2 (45) | 0.163 | 79.2 (145) | 55.2 (16) | 0.009 |

| Multiple HPV infection | 67.7 (63) | 50.4 (60) | 0.012 | 62.6 (92) | 47.7 (31) | 0.050 | 62.3 (114) | 31.0 (9) | 0.002 |

| 1 HPV type | 15.1 (14) | 20.2 (24) | 0.371 | 16.3 (24) | 21.5 (14) | 0.437 | 16.9 (31) | 24.1 (7) | 0.433 |

| 2 HPV types | 14.0 (13) | 16.0 (19) | 0.847 | 14.3 (21) | 15.4 (10) | 0.835 | 13.7 (25) | 17.2 (5) | 0.573 |

| 3 HPV types | 17.2 (16) | 10.9 (13) | 0.228 | 16.3 (24) | 9.2 (6) | 0.204 | 15.3 (28) | 3.4 (1) | 0.141 |

| 4–10 HPV types | 36.6 (34) | 23.5 (28) | 0.048 | 32.0 (47) | 23.1 (15) | 0.252 | 32.8 (60) | 10.3 (3) | 0.015 |

| HR-HPV | 66.7 (62) | 55.5 (66) | 0.120 | 61.9 (91) | 56.9 (37) | 0.544 | 63.4 (116) | 41.4 (12) | 0.040 |

| Probable HR/LR-HPV | 69.9 (65) | 56.3 (67) | 0.047 | 68.0 (100) | 53.8 (35) | 0.063 | 67.2 (123) | 37.9 (11) | 0.003 |

| Ureaplasma urealyticum | Ureaplasma parvum | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPV Vaccine/Type | % (n) | PR (95% CI) | p-Value | % (n) | PR (95% CI) | p-Value | |||

| Cervarix® | UU neg | 7.6 (9/119) | Reference | UP neg | 20.0 (13/65) | Reference | |||

| Cervarix® | UU pos | 19.4 (18/93) | 2.56 (1.23–5.37) | 0.013 | UP pos | 9.5 (14/147) | 0.48 (0.24–0.95) | 0.044 | |

| Gardasil4® | UU neg | 13.4 (16/119) | Reference | UP neg | 27.7 (18/65) | Reference | |||

| Gardasil4® | UU pos | 29.0 (27/93) | 2.16 (1.25–3.75) | 0.006 | UP pos | 17.7 (26/147) | 0.64 (0.38–1.09) | 0.103 | |

| Gardasil9® | UU neg | 33.6 (40/119) | Reference | UP neg | 41.5 (27/65) | Reference | |||

| Gardasil9® | UU pos | 57.0 (53/93) | 1.70 (1.25–2.32) | 0.001 | UP pos | 45.6 (67/147) | 1.10 (0.80–1.56) | 0.654 | |

| HPV6 | UU neg | 5.6 (7/119) | Reference | UP neg | 13.8 (9/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV6 | UU pos | 8.6 (8/93) | 1.46 (0.57–3.75) | 0.591 | UP pos | 4.1 (6/147) | 0.29 (0.11–0.77) | 0.018 | |

| HPV11 | UU neg | 2.5 (3/119) | Reference | UP neg | 1.5 (1/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV11 | UU pos | 1.1 (1/93) | 0.43 (0.06–2.92) | 0.633 | UP pos | 2.0 (3/147) | 1.33 (0.20–9.20) | >0.999 | |

| HPV16 | UU neg | 4.2 (5/119) | Reference | UP neg | 13.8 (9/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV16 | UU pos | 14.0 (13/93) | 3.33 (1.28–8.71) | 0.013 | UP pos | 6.1 (9/147) | 0.44 (0.19–1.04) | 0.105 | |

| HPV18 | UU neg | 4.2 (5/119) | Reference | UP neg | 13.8 (9/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV18 | UU pos | 12.9 (12/93) | 3.07 (1.17–8.13) | 0.024 | UP pos | 5.4 (8/147) | 0.39 (0.16–0.95) | 0.053 | |

| HPV31 | UU neg | 7.6 (9/119) | Reference | UP neg | 4.6 (3/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV31 | UU pos | 5.4 (5/93) | 0.71 (0.26–1.95) | 0.588 | UP pos | 7.5 (11/147) | 1.62 (0.51–5.31) | 0.558 | |

| HPV33 | UU neg | 0.9 (1/119) | Reference | UP neg | 0.0 (0/65) | … | |||

| HPV33 | UU pos | 3.2 (3/93) | 3.84 (0.56–26.56) | 0.323 | UP pos | 2.7 (4/147) | … | ||

| HPV45 | UU neg | 9.2 (11/119) | Reference | UP neg | 7.7 (5/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV45 | UU pos | 8.6 (8/93) | 1.28 (0.59–2.76) | 0.651 | UP pos | 9.5 (14/147) | 1.24 (0.49–3.22) | 0.798 | |

| HPV52 | UU neg | 6.7 (8/119) | Reference | UP neg | 6.2 (4/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV52 | UU pos | 11.8 (11/93) | 1.76 (0.76–4.10) | 0.230 | UP pos | 10.2 (15/147) | 1.66 (0.61–4.65) | 0.440 | |

| HPV58 | UU neg | 6.7 (8/119) | Reference | UP neg | 13.8 (9/65) | Reference | |||

| HPV58 | UU pos | 15.1 (14/93) | 2.24 (1.01–5.02) | 0.068 | UP pos | 8.8 (13/147) | 0.64 (0.30–1.41) | 0.329 | |

| Characteristics | Total | UU-HPV Co-Infected | PR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | |||

| Age | |||||

| 15–17 | 23 | 11 | 47.8 | Reference | |

| 18–19 | 61 | 45 | 73.8 | 1.54 (1.05–2.57) | 0.037 |

| 20–23 | 28 | 21 | 75.0 | 1.57 (1.01–2.65) | 0.080 |

| Ever smoke | |||||

| No | 95 | 65 | 68.4 | Reference | |

| Yes | 17 | 12 | 70.6 | 1.03 (0.67–1.35) | >0.999 |

| Sexual debut, years | |||||

| ≤15 years | 53 | 34 | 64.2 | Reference | |

| 16–17 years | 58 | 42 | 72.4 | 1.13 (0.87–1.48) | 0.415 |

| Number of lifetime sexual partnersΣ | |||||

| 1 | 26 | 13 | 50.0 | Reference | |

| 2 | 41 | 32 | 78.0 | 1.56 (1.08–2.49) | 0.031 |

| 3–6 | 39 | 31 | 79.5 | 1.59 (1.10–2.53) | 0.017 |

| Number of new sexual partners past 3 months; median (IQR)Σ | |||||

| 0 | 15 | 6 | 40.0 | Reference | |

| 1 | 74 | 58 | 78.4 | 1.96 (1.19–3.99) | 0.005 |

| 2–4 | 14 | 12 | 85.7 | 2.14 (1.19–2.42) | 0.021 |

| Frequency of vaginal sexual intercourse in the past 1 month | |||||

| 0 | 21 | 11 | 52.4 | Reference | |

| 1 | 29 | 19 | 65.5 | 1.25 (0.79–2.13) | 0.393 |

| 2–3 | 41 | 33 | 80.5 | 1.54 (1.06–2.53) | 0.037 |

| 4–10 | 13 | 13 | 100.0 | 1.91 (1.83–1.91) | 0.005 |

| Ever consumed alcohol Σ | |||||

| No | 22 | 9 | 40.9 | Reference | |

| Yes | 90 | 68 | 75.6 | 1.85 (1.20–3.28) | 0.004 |

| Drunk during last sexual intercourse Σ | |||||

| No | 94 | 70 | 74.5 | Reference | |

| Yes | 9 | 6 | 66.7 | 0.90 (0.47–1.23) | 0.694 |

| Ever pregnant Σ | |||||

| No | 83 | 56 | 67.5 | Reference | |

| Yes | 29 | 21 | 72.4 | 1.07 (0.78–1.37) | 0.816 |

| Currently on contraception Σ | |||||

| No | 29 | 21 | 72.4 | Reference | |

| Yes | 75 | 56 | 74.7 | 1.03 (0.82–1.41) | 0.808 |

| Condom use during last intercourse Σ | |||||

| No | 65 | 49 | 75.4 | Reference | |

| Yes | 38 | 27 | 71.1 | 0.94 (0.71–1.19) | 0.649 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kondlo, S.; Mbulawa, Z.Z.A. Ureaplasma Species and Human Papillomavirus Coinfection and Associated Factors Among South African Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Microbiol. Res. 2026, 17, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010003

Kondlo S, Mbulawa ZZA. Ureaplasma Species and Human Papillomavirus Coinfection and Associated Factors Among South African Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Microbiology Research. 2026; 17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleKondlo, Sinazo, and Zizipho Z. A. Mbulawa. 2026. "Ureaplasma Species and Human Papillomavirus Coinfection and Associated Factors Among South African Adolescent Girls and Young Women" Microbiology Research 17, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010003

APA StyleKondlo, S., & Mbulawa, Z. Z. A. (2026). Ureaplasma Species and Human Papillomavirus Coinfection and Associated Factors Among South African Adolescent Girls and Young Women. Microbiology Research, 17(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres17010003