Prospective Yeast Species with Enzymatic, Aromatic, and Antifungal Applications Isolated from Cocoa Fermentation in Various Producing Areas in Côte d’Ivoire

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cocoa Fermentation and Yeast Isolation

2.2. Reference Ochratoxinogenic Molds Strains

2.3. Molecular Identification of Yeasts

2.4. Production of Extracellular Hydrolytic Enzymes: Ability of Yeast Species

2.5. Production of Aroma Compounds

- : Amount of compound i released into the headspace, expressed in µg·mL−1;

- : Peak area of compound I;

- : Volume of sample suspension introduced into the vial (mL);

- : Peak area of the internal standard (3-heptanol);

- 0.818: Mass of the internal standard in µg.

2.6. Preparation of Yeast and Fungal Spore Suspensions

2.6.1. Antifungal Activity of Yeasts by Direct Confrontation

2.6.2. Antifungal Activity of Non-Volatile Yeast Metabolites

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Yeast Species Diversity

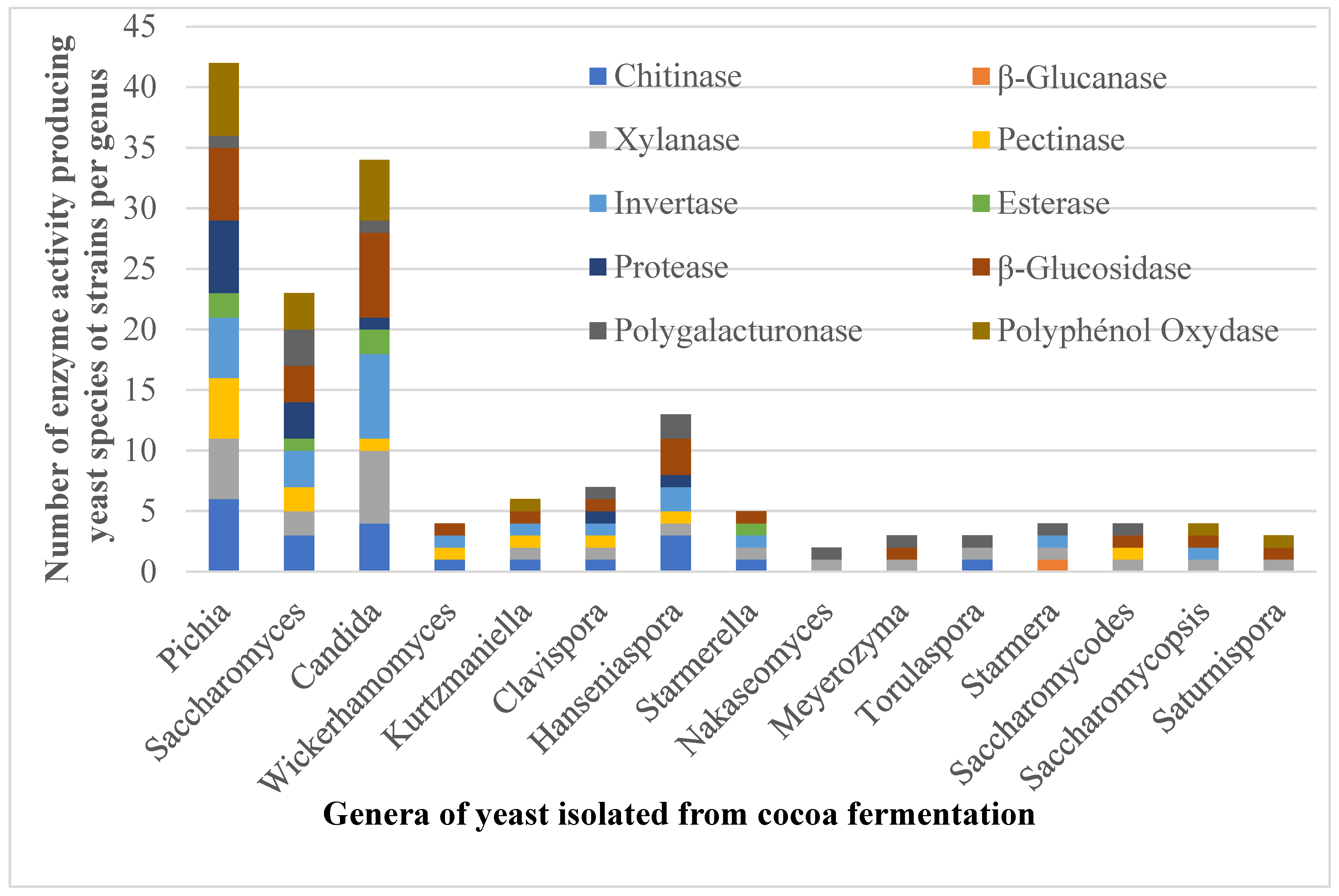

3.2. Extracellular Hydrolytic Enzyme Produced by Identified Yeast Species

3.3. Aromatic Compounds Produced by Identified Yeast Species

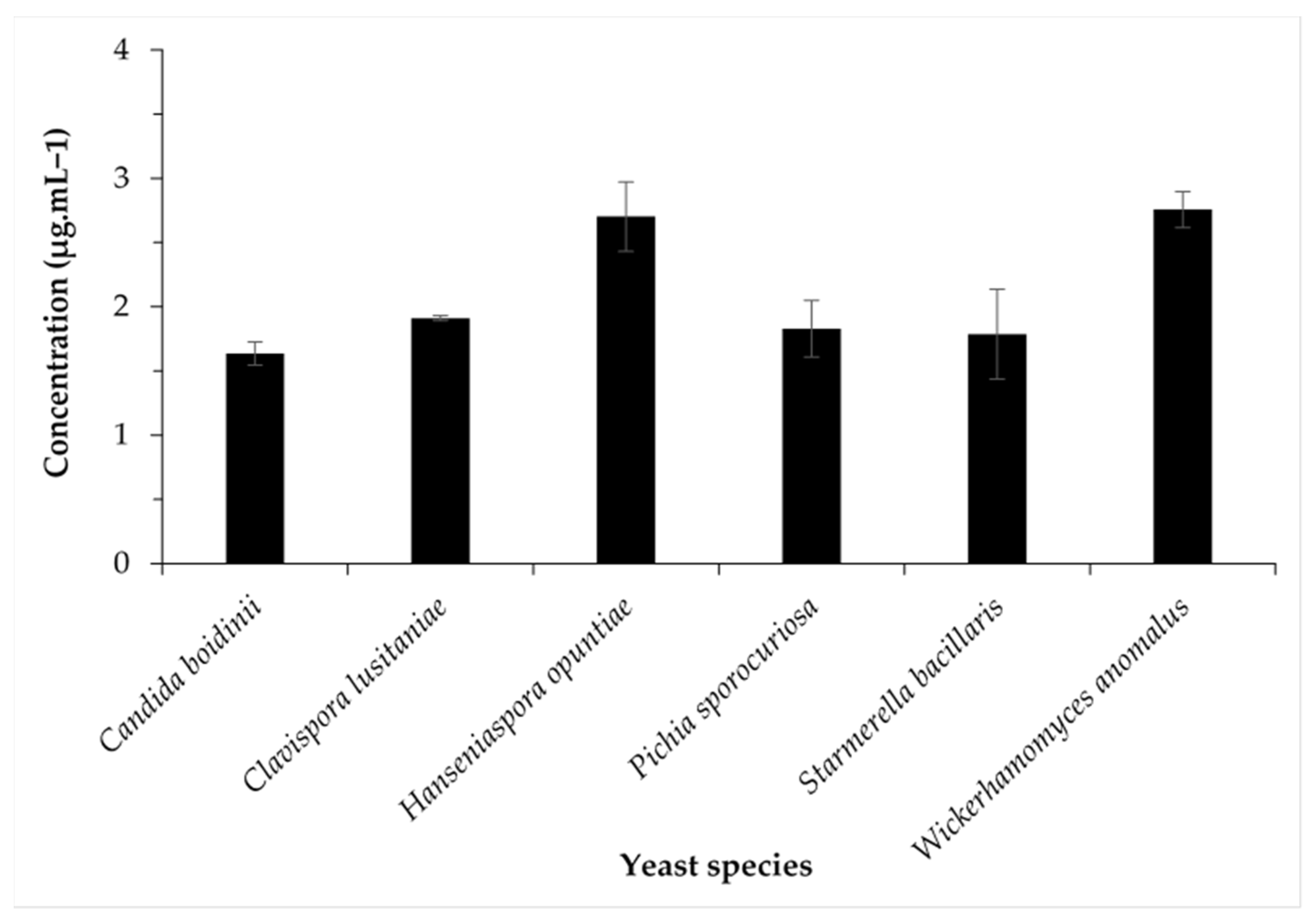

3.4. Changes in Concentrations of Major Aromatic Compounds of Some Chemical Families Produced by Identified Yeast Species

3.5. Antifungal Activity of Identified Yeast Species Against Ochratoxigenic Molds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iorizzo, M.; Bagnoli, D.; Vergalito, F.; Testa, B.; Tremonte, P.; Succi, M.; Pannella, G.; Letizia, F.; Albanese, G.; Lombardi, S.J. Coppola Raffaele Diversity of Fungal Communities on Cabernet and Aglianico Grapes from Vineyards Located in Southern Italy. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1399968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiegbu, F.O. Biotechnology: History, processes, and prospects in forestry. In Forest Microbiology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitessa, D.A. Review on effect of fermentation on physicochemical properties, anti-nutritional factors and sensory properties of cereal-based fermented foods and beverages. Ann. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Jeyaram, K. Role of Yeasts in Food Fermentation. In Yeast Diversity in Human Welfare; Satyanarayana, T., Kunze, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craparo, V.; Viola, E.; Vella, A.; Prestianni, R.; Pirrone, A.; Naselli, V.; Amato, F.; Oliva, D.; Notarbartolo, G.; Guzzon, R.; et al. Oenological capabilities of yeasts isolated from high-sugar matrices (Manna and Honey) as potential ctarters and Co-starters for winemaking. Beverages 2024, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.A.; Echavarri-Erasun, C. Yeast biotechnology. In The Yeasts; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadjo, A.C.; Houphouët, K.R.; Koné, K.M.; Fontana, A.; Durand, N.; Montet, D.; Guéhi, T.S. Link between the Reduction of Ochratoxin A and Free Fatty Acids Production in Cocoa Beans Using Bacillus sp. and the Sensory Perception of Chocolate Produced Thereof. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2024, 7, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouassi, A.D.D.; Koné, K.M.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Lebrun, M.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; Guéhi, T.S. Effect of spontaneous fermentation location on the fingerprint of volatile compound precursors of cocoa and the sensory perceptions of the end-chocolate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 4466–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kédjébo, K.B.D.; Guéhi, T.S.; Brou, K.; Durand, N.; Aguilar, P.; Fontana-Tachon, A.; Montet, D. Effect of post-harvest treatments on the occurrence of ochratoxin A in cocoa beans. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2015, 33, 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Kouakou, B.J.; Irie, B.Z.; Dick, E.; Nemlin, G.; Bomisso, L.E. Caractérisation des techniques de séchage du cacao dans les principales zones de production en Côte d’Ivoire et détermination de leur influence sur la qualité des fèves commercialisées. J. Appl. Biosci. 2023, 64, 4797–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Yang, L.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Fu, J.; Liu, G.; Kan, Q.; Ho, C.-T.; Huang, O.; Cao, Y. Applications of multi-omics techniques to unravel the fermentation process and the flavor formation mechanism in fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 8367–8383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragab, W.S.; Gomah, N.H.; Abdein, M.A. Biological Control of Mold and Mycotoxin Contaminations in Food and Dairy Products. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2020, 9, 1128–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.A.; Strub, C.; Fontana, A.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Crop molds and mycotoxins: Alternative management using biocontrol. Biol. Control 2017, 104, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Lozano, C.J.; Caballero-Torres, D.; López-Giraldo, L.J. Screening wild yeast isolated from cocoa bean fermentation using volatile compounds profile. Molecules 2022, 27, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Ríos, H.G.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.L.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; Castellanos-Onorio, O.P.; Alonso-Villegas, R.; Rayas-Duarte, P.; Cano-Sarmiento, C.; Figuero-Hermandez, C.Y.; González-Rios, O. Yeasts as producers of flavor precursors during cocoa bean fermentation and their relevance as starter cultures: A review. Fermentation 2022, 8, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi-Clair, B.J.; Koné, M.K.; Kouamé, K.; Lahon, M.C.; Berthiot, L.; Durand, N.; Lebrun, M.; Julien-Ortiz, A.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; et al. Effect of aroma potential of Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation on the volatile profile of raw cocoa and sensory attributes of chocolate produced thereof. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, M.K.; Guéhi, S.T.; Durand, N.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Berthiot, L.; Tachon, A.F.; Brou, K.; Boulanger, R.; Montet, D. Contribution of predominant yeasts to the occurrence of aroma compounds during cocoa bean fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2016, 89, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csutak, O.; Csutak, T. Phylogenetic Analysis and Characterization of an Alkane-Degrading Yeast Strain Isolated from Oil-Polluted Soil. Turk. J. Biol. 2014, 38, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigrero-Vaca, J.; Maridueña-Zavala, M.G.; Liao, H.L.; Prado-Lince, M.; Zambrano-Vera, C.S.; Monserrate-Maggi, B.; Cevallos-Cevallos, J.M. Microbial diversity and contribution to the formation of volatile compounds during fine-flavor cacao bean fermentation. Foods 2022, 11, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodadadi, H.; Karimi, L.; Jalalizand, N.; Adin, H.; Mirhendi, H. Utilization of size polymorphism in ITS1 and ITS2 regions for identification of pathogenic yeast species. J. Med. Microbiol. 2017, 66, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saoudi, B.; Habbeche, A.; Kerouaz, B.; Haberra, S.; Romdhane, Z.B.; Tichati, L.; Boudelaa, M.; Belghith, H.; Gargouri, A.; Ladjama, A. Purification and characterization of a new thermoalkaliphilic pectate lyase from Actinomadura keratinilytica Cpt20. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moubasher, H.; Wahsh, S.S.; El-Kassem, N.A. Purification of pullulanase from Aureobasidium pullulans. Microbiology 2010, 79, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavaro, S.L.; Susca, A.; Frisvad, J.C.; Tufariello, M.; Chytiri, A.; Perrone, G.; Mita, G.; Logrieco, A.F.; Bleve, G. Isolation, characterization, and selection of molds associated to fermented black table olives. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, M.L.A.; Jolly, N.P.; Lambrechts, M.G.; Van Rensburg, P. Screening for the production of extracellular hydrolytic enzymes by non-Saccharomyces wine yeasts. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Acquaticci, L.; Molina-Hernandez, J.B.; Rantsiou, K.; Martuscelli, M.; Kamgang-Nzekoue, A.F.; Vittori, S.; Paparella, A.; Chaves-López, C. Exploring the capability of yeasts isolated from Colombian fermented cocoa beans to form and degrade biogenic amines in a lab-scale model system for cocoa fermentation. Microorganisms 2020, 9, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdouche, Y.; Guehi, T.; Durand, N.; Kedjebo, K.B.D.; Montet, D.; Meile, J.C. Dynamics of microbial ecology during cocoa fermentation and drying: Towards the identification of molecular markers. Food Control 2015, 48, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waehrens, S.; Zhang, S.; Hedelund, P.; Petersen, M.; Byrne, D. Application of the fast sensory method ‘Rate-All-That-Apply’ in chocolate quality control compared with DHS-GC-MS. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1877–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Rojas, L.L.; Oliva-Cruz, S.M.; Rondinel-Mendoza, N.V.; Villegas-Vilchez, L.F.; Caetano, A.C. Identification, semi-quantification, and dynamics of volatile organic compounds during spontaneous fermentation of two cocoa varieties from northern Peru, using HS-SPME/GC-MS techniques. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, e0000072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, M.; Petersen, M.; Heimdal, H. Effect of fermentation method, roasting and conching conditions on the aroma volatiles of dark chocolate. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2012, 36, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llano, S.; Vaillant, F.; Santander, M.; Zorro-González, A.; González-Orozco, C.E.; Maraval, I.; Boulanger, R.; Escobar, S. Exploring the Impact of Fermentation Time and Climate on Quality of Cocoa Bean-Derived Chocolate: Sensorial Profile and Volatilome Analysis. Foods 2024, 13, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadjo, A.C.; Beugre, G.C.; Sess-Tchotch, D.A.; Kedjebo, K.B.D.; Mounjouenpou, P.; Durand, N.; Fontana, A.; Guehi, S.T. Screening of anti-fungal Bacillus strains and influence of their application on cocoa beans fermentation and final bean quality. J. Adv. Microbiol. 2023, 23, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verce, M.; Schoonejans, J.; Hernandez Aguirre, C.; Molina-Bravo, R.; De Vuyst, L.; Weckx, S. A combined metagenomics and metatranscriptomics approach to unravel Costa Rican cocoa box fermentation processes reveals yet unreported microbial species and functionalities. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 641185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, H.G.; Niamké, S.L. Mapping the functional and strain diversity of the main microbiota involved in cocoa fermentation from Cote d’Ivoire. Food Microbiol. 2021, 98, 103767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdouche, Y.; Meile, J.C.; Lebrun, M.; Guehi, T.; Boulanger, R.; Teyssier, C.; Montet, D. Impact of turning, pod storage and fermentation time on microbial ecology and volatile composition of cocoa beans. Food Res. Int. 2019, 119, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, N.N.; Ramos, C.L.; Ribeiro, D.D.; Pinheiro, A.C.M.; Schwan, R.F. Dynamic behavior of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia kluyveri and Hanseniaspora uvarum during spontaneous and inoculated cocoa fermentations and their effect on sensory characteristics of chocolate. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jespersen, L.; Nielsen, D.S.; Hønholt, S.; Jakobsen, M. Occurrence and diversity of yeasts involved in fermentation of West African cocoa beans. FEMS Yeast Res. 2005, 5, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Muñoz, C.; De Vuyst, L. Functional yeast starter cultures for cocoa fermentation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Leroy, F. Functional role of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in cocoa fermentation processes. Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 432–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas Junior, G.C.A.; de Espírito-Santo, J.C.A.; Ferreira, N.R.; Marques-da-Silva, S.H.; Oliveira, G.; Vasconcelos, S.; de Almeida, S.F.O.; Silva, L.R.C.; Gobira, R.M.; de Figueiredo, H.M.; et al. Yeast isolation and identification during On-Farm Cocoa Natural Fermentation in a Highly Producer Region in Northern Brazil. Sci. Plena 2021, 16, 121502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.E.; del Olmo, M.; Burri, C. Enzyme activities in cocoa beans during fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1998, 77, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fleet, G. Yeasts are essential for cocoa bean fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 174, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maura, Y.F.; Balzarini, T.; Borges, P.C.; Evrard, P.; De Vuyst, L.; Daniel, H.M. The environmental and intrinsic yeast diversity of Cuban cocoa bean heap fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 233, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samagaci, L.; Ouattara, H.G.; Goualié, B.G.; Niamke, S.L. Growth capacity of yeasts potential starter strains under cocoa fermentation stress conditions in Ivory Coast. Emir. J. Food Agric. (EJFA) 2014, 26, 861–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mager, W.H.; Ferreira, P.M. Stress response of yeast. Biochem. J. 1993, 290 Pt 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, D.; Bandara, A.; Fraser, S.; Chambers, P.J.; Stanley, G.A. The ethanol stress response and ethanol tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, J.K.; Panatta, A.A.S.; Silveira, M.A.D.; Tav, C.; Johann, S.; Rodrigues, M.L.F.; Martins, C.V.B. Yeasts isolated from a lotic continental environment in Brazil show potential to produce amylase, cellulase and protease. Biotechnol. Rep. 2021, 30, e00630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koffi, O.; Samagaci, L.; Goualie, B.; Niamke, S. Screening of potential yeast starters with high ethanol production for a small-scale cocoa fermentation in Ivory Coast. Food Environ. Saf. J. 2018, 17, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, L.S.; Rocha, F.D.S.; Silveira, P.T.D.S.; Bispo, E.D.S.; Soares, S.E. Enzymatic activity of proteases and its isoenzymes in fermentation process in cultivars of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) produced in southern Bahia, Brazil. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freimüller Leischtfeld, S.; Hämmerli, A.; Lehmann, A.; Tönz, A.; Beck, B.M.; Wild, J.; Weis, S.; Neutsch, L.; Miescher Schwenninger, S. Wickerhamomyces pijperi: An Up-And-Coming Yeast with Pectinolytic Activity Suitable for Cocoa Bean Fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulindwa, J.; Atukwase, A.; Bitalo, D.N.; Archileo, N.K. On-farm cocoa fermentation practices and their effect on the quality of cocoa beans in three agroecological zones of uganda. Eur. J. Nutr. Andamp Food Saf. 2025, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samagaci, L.; Ouattara, H.G.; Goualié, B.; Niamké, S. Polyphasic analysis of pectinolytic and stress-resistant yeast strains isolated from Ivorian cocoa fermentation. J. Food Res. 2014, 4, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.P.F.; Bezerra, C.O.; Casteliano, G.A.; Uetanabaro, A.P.T.; da Silva, E.G.P.; da Costa, A.M. Production of enzyme for Pleurotus pulmonarius by solid-state fermentation on peach-palm and cocoa waste. Fine Chem. Eng. 2025, 6, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.B.D.C.; e Silva, M.B.D.C.; de Souza Silveira, P.T.; Marques, E.D.L.S.; Soares, S.E. Extraction and determination of invertase and polyphenol oxidase activities during cocoa fermentation Extração e determinação da atividade de invertase e polifenoloxidase durante fermentação de cacau. Braz. J. Dev. 2021, 7, 80316–80330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersman, E.; Struyf, N.; Kyomugasho, C.; Jamsazzadeh Kermani, Z.; Santiago, J.S.; Baert, E.; Hemdane, S.; Vrancken, G.; Courtin, C.M.; Hendrickx, M.; et al. Characterization and degradation of pectic polysaccharides in cocoa pulp. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 9726–9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, H.G.; Koffi, B.L.; Karou, G.T.; Sangaré, A.; Niamke, S.L.; Diopoh, J.K. Implication of Bacillus sp. in the production of pectinolytic enzymes during cocoa fermentation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ospina, J.; Molina-Hernández, J.B.; Chaves-López, C.; Romanazzi, G.; Paparella, A. The role of fungi in the cocoa production chain and the challenge of climate change. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visintin, S.; Ramos, L.; Batista, N.; Dolci, P.; Schwan, F.; Cocolin, L. Impact of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Torulaspora delbrueckii starter cultures on cocoa beans fermentation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 257, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ooi, T.S.; Sepiah, M.; Khairul Bariah, S. Effect of yeast species on total soluble solids, total polyphenol content and fermentation index during simulation study of cocoa fermentation. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. Innov. 2016, 3, 477–483. [Google Scholar]

- Macedo, A.S.L.; Rocha, F.D.S.; Ribeiro, M.D.S.; Soares, S.E.; Bispo, E.D.S. Characterization of polyphenol oxidase in two cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) cultivars produced in the south of Bahia, Brazil. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 36, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, H.M.; Vrancken, G.; Takrama, J.F.; Camu, N.; De Vos, P.; De Vuyst, L. Yeast diversity of Ghanaian cocoa bean heap fermentations. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 774–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirko, B.; Mitiku, H.; Getu, A. Role of fermentation and microbes in cacao fermentation and their impact on cacao quality. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanuf. 2023, 3, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwan, R.F.; Wheals, A.E. The microbiology of cocoa fermentation and its role in chocolate quality. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.D.M.; Martínez-Burgos, W.J.; dos Reis, G.A.; Ocán-Torres, D.Y.; dos Santos Costa, G.; Rosas Vega, F.; Badel, A.B.; Coronado, L.S.; Serra, J.L.; Soccol, C.R. The Role of Microbial Dynamics, Sensorial Compounds, and Producing Regions in Cocoa Fermentation. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C.; Luca, S.V.; Miron, A. Flavor chemistry of cocoa and cocoa products—An overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, T.B.; Babat, R.H.; Zorn, H.; Gola, S.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U. Enzyme-assisted hydrolysis of Theobroma cacao L. pulp. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, S.D.F.O.D.; Silva, L.R.C.; Junior, G.C.A.C.; Oliveira, G.; Silva, S.H.M.D.; Vasconcelos, S.; Lopes, A.S. Diversity of yeasts during fermentation of cocoa from two sites in the Brazilian Amazon. Acta Amaz. 2019, 49, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, O.D.S.; Chagas-Junior, G.C.; Chisté, R.C.; Martins, L.H.D.S.; Andrade, E.H.D.A.; Nascimento, L.D.D.; Lopes, A.S. Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia manshurica from Amazonian biome affect the parameters of quality and aromatic profile of fermented and dried cocoa beans. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 4148–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Enríquez, L.; Vila-Crespo, J.; Rodríguez-Nogales, J.M.; Fernández-Fernández, E.; Ruipérez, V. Non-Saccharomyces yeasts from organic vineyards as spontaneous fermentation agents. Foods 2023, 12, 3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purbaningrum, K.; Hidayat, C.; Witasari, L.D.; Utami, T. Flavor precursors and volatile compounds improvement of unfermented cocoa beans by hydrolysis using bromelain. Foods 2023, 12, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santander Muñoz, M.; Rodríguez Cortina, J.; Vaillant, F.E.; Escobar Parra, S. An overview of the physical and biochemical transformation of cocoa seeds to beans and to chocolate: Flavor formation. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 60, 1593–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Alayo, E.M.; Idrogo-Vásquez, G.; Siche, R.; Cardenas-Toro, F.P. Formation of aromatic compounds precursors during fermentation of Criollo and Forastero cocoa. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa-Hernández, C.; Mota-Gutierrez, J.; Ferrocino, I.; Hernández-Estrada, Z.J.; González-Ríos, O.; Cocolin, L.; Suárez-Quiroz, M.L. The challenges and perspectives of the selection of starter cultures for fermented cocoa beans. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 301, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Gutierrez, J.; Barbosa-Pereira, L.; Ferrocino, I.; Cocolin, L. Traceability of functional volatile compounds generated on inoculated cocoa fermentation and its potential health benefits. Nutrients 2019, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, K.M.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Kouassi, A.D.D.; Yao, A.K.; Ban-Koffi, L.; Durand, N.; Guéhi, T.S. Pod storage time and spontaneous fermentation treatments and their impact on the generation of cocoa flavour precursor compounds. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 2516–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez-Araque, R.H.; Landines-Vera, E.F.; Urresto-Villegas, J.C.; Caicedo-Jaramillo, C.F. Microorganisms during cocoa fermentation: Systematic review. Foods Raw Mater. 2020, 8, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulce, V.R.; Anne, G.; Manuel, K.; Carlos, A.A.; Jacobo, R.C.; de Jesús, C.E.S.; Eugenia, L.C. Cocoa bean turning as a method for redirecting the aroma compound profile in artisanal cocoa fermentation. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, M.; Wu, S.; Lin, P.; Zeng, T.; Luo, H.; Huang, D.; et al. Transcriptomics to evaluate the influence mechanisms of ethanol on the ester production of Wickerhamomyces anomalus with the induction of lactic acid. Food Microbiol. 2024, 122, 104556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadow, D.; Bohlmann, J.; Phillips, W.; Lieberei, R. Identification of main fine flavour components in two genotypes of the cocoa tree (Theobroma cacao L.). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2013, 86, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criollo-Nuñez, J.; Sandoval-Aldana, A.P.; Bolívar, G.; Ramírez Toro, C. Selection of promising yeasts for starter culture development promoter of cocoa fermentation. Ing. Compet. 2024, 26, e20413296. [Google Scholar]

- Frauendorfer, F.; Schieberle, P. Key aroma compounds in fermented Forastero cocoa beans and changes induced by roasting. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza Salazar, M.M.; Martínez Álvarez, O.L.; Ardila Castañeda, M.P.; Lizarazo and Medina, P.X. Bioprospecting of indigenous yeasts involved in cocoa fermentation using sensory and chemical strategies for selecting a starter inoculum. Food Microbiol. 2022, 101, 103896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coria-Hinojosa, L.M.; Velásquez-Reyes, D.; Alcazar-Valle, M.; Kirchmayr, M.R.; Calva-Estrada, S.; Gschaedler, A.; Gschaedler, A.; Lugo, E. Exploring volatile compounds and microbial dynamics: Kluyveromyces marxianus and Hanseniaspora opuntiae reduce Forastero cocoa fermentation time. Food Res. Int. 2024, 193, 114821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choińska, R.; Piasecka-Jóźwiak, K.; Chabłowska, B.; Dumka, J.; Łukaszewicz, A. Biocontrol ability and volatile organic compounds production as a putative mode of action of yeast strains isolated from organic grapes and rye grains. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 1135–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Hernández, A.; Galvan, A.I.; Córdoba, M.G.; Casquete, R.; Serradilla, M.J.; Martín, A. Selection and application of antifungal VOCs-producing yeasts as biocontrol agents of grey mould in fruits. Food Microbiol. 2020, 92, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olana, R.C.; Haituk, S.; Karunarathna, A.; Cumagun, C.J.R. Elucidating the Efficacy of Antagonistic Yeasts by Using Multiple Mechanisms in Controlling Fungal Phytopathogens. J. Phytopathol. 2025, 173, e70097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggirello, M.; Nucera, D.; Cannoni, M.; Peraino, A.; Rosso, F.; Fontana, M.; Cocolin, L.; Dolci, P. Antifungal activity of yeasts and lactic acid bacteria isolated from cocoa bean fermentations. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewa-Ngongang, M.; du Plessis, H.W.; Ntwampe, S.K.O.; Chidi, B.S.; Hutchinson, U.F.; Mekuto, L.; Jolly, N.P. The use of Candida pyralidae and Pichia kluyveri to control spoilage microorganisms of raw fruits used for beverage production. Foods 2019, 8, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hathout, A.; Abdel-Nasser, A. The efficiency of Saccharomyces cerevisiae as an antifungal and antimycotoxigenic agent. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, C.; Yan, T.; Li, B.; Wang, S.; Gong, D.; Long, D. Antifungal potentiality of non-volatile compounds produced from Hanseniaspora uvarum against postharvest decay of table grape fruit caused by Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 222, 113364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabañas, C.M.; Hernández León, A.; Ruiz-Moyano, S.; Merchán, A.V.; Martínez Torres, J.M.; Martín, A. Biocontrol of Cheese Spoilage Moulds Using Native Yeasts. Foods 2025, 14, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluleke, E.; Jolly, N.P.; Patterton, H.G.; Setati, M.E. Antifungal activity of non-conventional yeasts against Botrytis cinerea and non-Botrytis grape bunch rot fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 986229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, T.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Sun, R.; Yang, M. Antagonistic effects of volatile organic compounds of Saccharomyces cerevisiae NJ-1 on the growth and toxicity of Aspergillus flavus. Biol. Control 2023, 177, 105093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, S.; Balachandar, D.; Senthil, N.; Velazhahan, R.; Paranidharan, V. Volatiles of antagonistic soil yeasts inhibit growth and aflatoxin production of Aspergillus flavus. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 263, 127150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, A.I.; Hernandez, A.; de Guía Córdoba, M.; Martin, A.; Serradilla, M.J.; Lopez-Corrales, M.; Rodriguez, A. Control of toxigenic Aspergillus spp. in dried figs by volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from antagonistic yeasts. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 376, 109772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vepštaitė-Monstavičė, I.; Lukša-Žebelovič, J.; Apšegaitė, V.; Mozūraitis, R.; Lisicinas, R.; Stanevičienė, R.; Blažytė-Čereškienė, L.; Serva, S.; Servienė, E. Profiles of killer systems and volatile organic compounds of rowanberry and rosehip-inhabiting yeasts substantiate implications for biocontrol. Foods 2025, 14, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Components | Concentration (g·L−1) |

|---|---|

| Yeast nitrogen base (YNB) | 2.0 |

| Fructose | 30.0 |

| Glucose | 20.0 |

| Pectin | 10.0 |

| Sucrose | 6.7 |

| Acetic acid | 1.4 |

| Lactic acid | 1.0 |

| Citric acid | 1.0 |

| Ammonium sulfate (NH4)2SO4 | 2.8 |

| Monobasic potassium phosphate (KH2PO4) | 1.0 |

| Dibasic potassium phosphate (K2HPO4) | 6.0 |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (MgSO4·7H2O) | 0.5 |

| Iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O) | 0.01 |

| Analytic Ethanol | 2.0 |

| Polyphenols (catechin 1136 mg·L−1, epicatechin 1441 mg·L−1, isoquercetin 539 mg·L−1) | 0.051% |

| Yeasts Isolated | Cocoa Fermentations Areas | Frequence (%) | Dominance (%) | % Identity | GenBank Accession Number | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genera | Species | Adzopé | Agnibilékrou | Biankouma | Bonon | Divo | Guiberoua | Maféré | Meagui | ||||

| Candida | berthetii | 1 | 1 | 25 | 0.72 | 99 | NR_077118.1 | ||||||

| boidinii | 3 | 13 | 1.08 | 100 | KY445950.1 | ||||||||

| incommunis | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | MZ506857.1 | ||||||||

| tropicalis | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 75 | 5.38 | 100 | LC317537.1 | |||

| Clavispora | lusitaniae | 8 | 13 | 2.87 | 100 | KP674846.1 | |||||||

| Cyberlindnera | sp. | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | PP112176.1 | |||||||

| Geotrichum | candidum | 3 | 13 | 1.08 | 99 | MT071788.1 | |||||||

| Hanseniaspora | opuntiae | 5 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 88 | 9.32 | 100 | FM199955.1 | |

| pseudoguilliermondii | 2 | 13 | 0.72 | 100 | MW990151.1 | ||||||||

| Kluyveromyces | marxianus | 2 | 13 | 0.72 | 100 | MT187614.1 | |||||||

| Kurtzmaniella | quercitrusa | 4 | 2 | 25 | 2.15 | 100 | MF574303.1 | ||||||

| Meyerozyma | caribbica | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | MT312818.1 | |||||||

| Nakaseomyces | glabratus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 38 | 1.08 | 100 | MK998697.1 | |||||

| Pichia | bruneiensis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 38 | 1.08 | 98 | LC431631.2 | |||||

| ethanolica | 1 | 5 | 1 | 38 | 2.51 | 100 | KM368822.1 | ||||||

| kluyveri | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 63 | 2.15 | 100 | KM982973.1 | ||||

| kudriavzevii | 5 | 16 | 18 | 7 | 8 | 13 | 15 | 11 | 100 | 33.33 | 100 | JQ808004.1 | |

| manshurica | 4 | 2 | 2 | 38 | 2.87 | 100 | OR554031.1 | ||||||

| pseudolambica | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | OP418367.1 | ||||||||

| sporocuriosa | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | FJ153179.1 | ||||||||

| terricola | 1 | 1 | 25 | 0.72 | 100 | KY495764.1 | |||||||

| Rhodotorula | mucilaginosa | 2 | 13 | 0.72 | 100 | MT465994.1 | |||||||

| paludigena | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | MN515011.1 | ||||||||

| Saccharomyces | cerevisiae | 4 | 9 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 100 | 15.77 | 100 | KY816904.1 |

| Saccharomycodes | ludwigii | 1 | 2 | 25 | 1.08 | 100 | OR554100.1 | ||||||

| Saccharomycopsis | amapae | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 97 | HG939418.1 | |||||||

| Saturnispora | diversa | 3 | 2 | 25 | 1.79 | 96 | KT175190.1 | ||||||

| Starmera | stellimalicola | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | KM982969.1 | |||||||

| Starmerella | bacillaris | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | KT029752.1 | |||||||

| Torulaspora | delbrueckii | 1 | 13 | 0.36 | 100 | MK267708.1 | |||||||

| Wickerhamomyces | anomalus | 4 | 7 | 4 | 38 | 5.38 | 100 | HM044864.1 | |||||

| Unidentified yeast isolates | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 75 | 3.94 | N/I | N/A | |||

| Total of yeast ioslates | 12 | 62 | 71 | 16 | 34 | 30 | 28 | 26 | |||||

| Total of identified yeast species | 5 | 20 | 14 | 7 | 11 | 6 | 5 | 8 | |||||

| Yeasts Isolated | Hydrolytic Enzymes Activity | Total of Hydrolytic Enzyme Activity Produced | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genera | Species | Chitinase | β-Glucanase | Xylanase | Pectinase | Invertase | Esterase | Protease | β-Glucosidase | Polygalac- turonase | Polyphenol Oxidase | |

| Candida | berthetii | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | 4 |

| boidinii | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | 6 | |

| incommunis | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | 8 | |

| tropicalis | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | 5 | |

| Clavispora | lusitaniae | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | 7 |

| Cyberlindnera | sp. | Not tested | ||||||||||

| Geotrichum | candidum | Not tested | ||||||||||

| Hanseniaspora | opuntiae | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | 4 |

| pseudoguilliermondii | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | 3 | |

| Kluyveromyces | marxianus | Not tested | ||||||||||

| Kurtzmaniella | quercitrusa | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | 7 |

| Meyerozyma | caribbica | Not tested | ||||||||||

| Nakaseomyces | glabratus | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | 2 |

| Pichia | bruneiensis | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | 7 |

| ethanolica | Not tested | |||||||||||

| kluyveri | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | 7 | |

| kudriavzevii | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | 7 | |

| manshurica | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 8 | |

| pseudolambica | Not tested | |||||||||||

| sporocuriosa | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | 7 | |

| terricola | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | 6 | |

| Rhodotorula | mucilaginosa | Not tested | ||||||||||

| paludigena | Not tested | |||||||||||

| Saccharomyces | cerevisiae | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | 8 |

| Saccharomycodes | ludwigii | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | - | 2 |

| Saccharomycopsis | amapae | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 6 |

| Saturnispora | diversa | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | 3 |

| Starmera | stellimalicola | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | - | 5 |

| Starmerella | bacillaris | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | - | 5 |

| Torulaspora | delbrueckii | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | - | 3 |

| Wickerhamomyces | anomalus | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | - | 4 |

| Unidentified yeast isolate | - | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | 5 | |

| Total number of each enzyme activity producing yeast species | 16 | 1 | 18 | 12 | 16 | 5 | 8 | 21 | 8 | 15 | 24 | |

| Number of each enzyme activity producing yeast species (%) | 66.66 | 3.16 | 75.0 | 50.0 | 66.66 | 20.83 | 33.33 | 87.5 | 33.33 | 62.5 | 100 | |

| Average of Concentration of Volatile Compounds per Chemical Family (µg·mL−1) Produced by Yeast Species | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeasts Species | Alcohols | Aldehydes | Ketones | Esters | Acids |

| Candida berthetii | 6.33 ± 0.27 j | 0.06 ± 0.01 nop | 7.78 ± 1.21 b | 23.16 ± 2.21 de | 1.2 ± 0.11 gh |

| Candida boidinii | 7.42 ± 0.47 hij | 0.09 ± 0.01 mno | 0.48 ± 0.02 nopq | 2.64 ± 0.13 mno | 1.64 ± 0.09 cd |

| Candida incommunis | 2.13 ± 0.21 lm | 0.61 ± 0.11 a | 0.72 ± 0 mno | 2.57 ± 0.46 mno | 0.55 ± 0.03 m |

| Candida tropicalis | 15.47 ± 1.27 c | 0.21 ± 0.03 efg | 1.19 ± 0.1 lm | 12.31 ± 0.79 gh | 1.51 ± 0.09 def |

| Clavispora lusitaniae | 10.43 ± 0.46 defg | 0.12 ± 0.01 jklm | 5.97 ± 0.55 d | 23.10 ± 2.08 de | 1.91 ± 0.02 b |

| Cyberlindnera sp. | 9.88 ± 0.59 efg | 0.13 ± 0.01 ijklm | 2.20 ± 0.19 hi | 11.67 ± 0.67 h | 1.05 ± 0.04 hijk |

| Geotrichum candidum | 3.62 ± 0.32 kl | 0.21 ± 0.01 ef | 1.45 ± 0.21 kl | 37.31 ± 2.67 c | 0.07 ± 0.01 n |

| Hanseniaspora opuntiae | 8.97 ± 1.07 fgh | 0.29 ± 0.01 d | 15.60 ± 0.85 a | 36.45 ± 4.17 c | 2.70 ± 0.27 a |

| Hanseniaspora pseudoguilliermondii | 9.03 ± 0.87 fgh | 0.11 ± 0.0l mn | 1.94 ± 0.21 ijk | 9.89 ± 0.47 hi | 0.96 ± 0.03 ijkl |

| Kluyveromyces marxianus | 14.48 ± 1.11 c | 0.22 ± 0.02 ef | 2.97 ± 0.06 g | 21.42 ± 1.26 e | 0.97 ± 0.15 hijk |

| Kurtzmaniella quercitrusa | 3.88 ± 0.13 k | 0.05 ± 0 op | 1.77 ± 0.05 ijk | 3.50 ± 0.39 lmn | 1.04 ± 0.04 hijk |

| Meyerozyma caribbica | 8.76 ± 0.6 ghi | 0.24 ± 0.02 e | 1.66 ± 0.07 ijkl | 3.68 ± 0.43 klm | 1.29 ± 0.09 fg |

| Nakaseomyces glabratus | 25.62 ± 4.38 a | 0.37 ± 0.02 c | 1.58 ± 0.13 jkl | 6.19 ± 0.65 jk | 1.01 ± 0.2 hijk |

| Pichia bruneinsis | 10.60 ± 0.8 def | 0.29 ± 0.02 d | 0.32 ± 0.01 nopq | 3.51 ± 0.42 lmn | 1.02 ± 0.23 hijk |

| Pichia ethanolica | 0.23 ± 0.01 c | 0.47 ± 0.1 b | 0.09 ± 0 q | 0.94 ± 0.13 no | 0.53 ± 0.07 m |

| Pichia kudriavzevii | 12.04 ± 0.37 d | 0.16 ± 0.01 hijk | 4.08 ± 0.52 f | 14.81 ± 4.79 fg | 1.33 ± 0.06 efg |

| Pichia kluyveri | 7.12 ± 0.84 ij | 0.11 ± 0.01 lmn | 5.07 ± 0.1 e | 48.33 ± 0.41 a | 0.92 ± 0.06 jkl |

| Pichia manshurica | 0.84 ± 0.04 mno | 0.04 ± 0 p | 0.40 ± 0.04 nopq | 0.38 ± 0.03 o | 0.07 ± 0.01 n |

| Pichia pseudolambica | 2.18 ± 0.11 lm | 0.05 ± 0 p | 0.51 ± 0.05 nopq | 2.41 ± 0.23 mno | 1.02 ±0.07 hijk |

| Pichia sporocuriosa | 2.03 ± 0.21 lmn | 0.10 ± 0 lmn | 0.11 ± 0.01 pq | 0.46 ± 0.03 o | 1.83 ± 0.22 bc |

| Pichia terricola | 11.61 ± 1.19 d | 0.11 ± 0.01 lmn | 3.73 ± 0.19 f | 14.99 ± 0.6 f | 1.14 ± 0.18 ghij |

| Rhodotorula mucilaginosa | 0.43 ± 0.04 no | 0.05 ± 0.01 op | 0.42 ± 0 nopq | 0.78 ± 0.07 o | 0.12 ± 0.01 n |

| Rhodotorula paludigena | 0.65 ± 0.09 mno | 0.07 ± 0.01 nop | 0.52 ± 0.02 nopq | 1.18 ± 0.22 mno | 0.90 ± 0.1 kl |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 14.27 ± 1.49 c | 0.21 ± 0.03 efg | 0.82 ± 0.1 mn | 6.69 ± 0.55 j | 1.45 ± 0.36 def |

| Saccharomycopsis amapae | 10.10 ± 0.53 de | 0.18 ± 0.01 fgh | 2.65 ± 0.03 gh | 24.95 ± 0.45 d | 1.29 ± 0.25 fg |

| Saturnispora diversa | 4.28 ± 1.20 k | 0.14 ± 0.01 hijkl | 0.19 ± 0.11 opq | 1.95 ± 3.81 mno | 0.73 ±0.01 lm |

| Saccharomycodes ludwigii | 8.19 ± 0.21 hi | 0.14 ± 0.02 hijkl | 0.63 ± 0.01 nop | 7.35 ± 0.24 ij | 1.18 ± 0.02 ghi |

| Starmerella bacillaris | 4.39 ± 0.14 k | 0.12 ± 0.01 klm | 2.12 ± 0.28 hij | 5.67 ± 0.91 jkl | 1.78 ± 0.07 bc |

| Starmera stellimalicola | 1.06 ± 0.2 mno | 0.17 ± 0.01 fghi | 7.09 ± 0.12 c | 17.26 ± 0.14 f | 0.60 ± 0.35 m |

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | 14.79 ± 0.55 c | 0.17 ± 0 ghij | 0.61 ± 0.05 nopq | 6.37 ± 0.34 j | 1.53 ± 0.04 de |

| Wickerhamomyces anomalus | 21.18 ± 0.44 b | 0.11 ± 0.0l mn | 16.00 ± 0.56 a | 43.69 ± 2.15 b | 2.76 ± 0.14 a |

| Mycotoxinogenic Mold Species | Mycelial Growth of Mycotoxinogenic Molds on YPDA | Yeast Species | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Antagonistic Effect | By Direct Confrontation | By Aroma Compounds | |

| Aspergillus carbonarius |  |  | All 32 tested yeast species |

|

| Aspergillus niger |  |  |

| |

| Aspergillus ochraceus |  |  | All yeast species were isolated except Pichia kudriavzevii, Candida tropicalis, Wickerhamomyces anomalus, and Saccharomycodes ludwigii | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, A.K.; Amien, G.F.K.; Assi-Clair, B.J.; Koné, N.; Koné, M.K.; Bethune, K.; Maraval, I.; Chochois, V.; Meile, J.-C.; Boulanger, R.; et al. Prospective Yeast Species with Enzymatic, Aromatic, and Antifungal Applications Isolated from Cocoa Fermentation in Various Producing Areas in Côte d’Ivoire. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120256

Yao AK, Amien GFK, Assi-Clair BJ, Koné N, Koné MK, Bethune K, Maraval I, Chochois V, Meile J-C, Boulanger R, et al. Prospective Yeast Species with Enzymatic, Aromatic, and Antifungal Applications Isolated from Cocoa Fermentation in Various Producing Areas in Côte d’Ivoire. Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(12):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120256

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Alfred Koffi, Guy Florent Kouamé Amien, Brice Judicaël Assi-Clair, Nabounou Koné, Mai Koumba Koné, Kevin Bethune, Isabelle Maraval, Vincent Chochois, Jean-Christophe Meile, Renaud Boulanger, and et al. 2025. "Prospective Yeast Species with Enzymatic, Aromatic, and Antifungal Applications Isolated from Cocoa Fermentation in Various Producing Areas in Côte d’Ivoire" Microbiology Research 16, no. 12: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120256

APA StyleYao, A. K., Amien, G. F. K., Assi-Clair, B. J., Koné, N., Koné, M. K., Bethune, K., Maraval, I., Chochois, V., Meile, J.-C., Boulanger, R., & Guéhi, S. T. (2025). Prospective Yeast Species with Enzymatic, Aromatic, and Antifungal Applications Isolated from Cocoa Fermentation in Various Producing Areas in Côte d’Ivoire. Microbiology Research, 16(12), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120256