Genome Insights into Kocuria sp. KH4, a Metallophilic Bacterium Harboring Multiple Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Kocuria Strains from Mine Tailings

2.2. Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

2.3. Genome Assembly and Functional Annotation

2.4. Phylogenomic and Pangenomic Analyses

2.5. Screening for Metal Resistance Genes (MRGs) and Genomic Islands (GIs)

2.6. Genome Mining to Identify Valuable Secondary Metabolites

3. Results

3.1. Functional Genomic Analysis of Kocuria sp. KH4

3.2. Genome-Based Taxonomy for Kocuria sp. KH4

3.3. Pangenome of Kocuria Genus

3.4. Metal Resistance Genes in Kocuria sp. KH4

3.5. Genomic Islands (GIs) in Kocuria sp. KH4

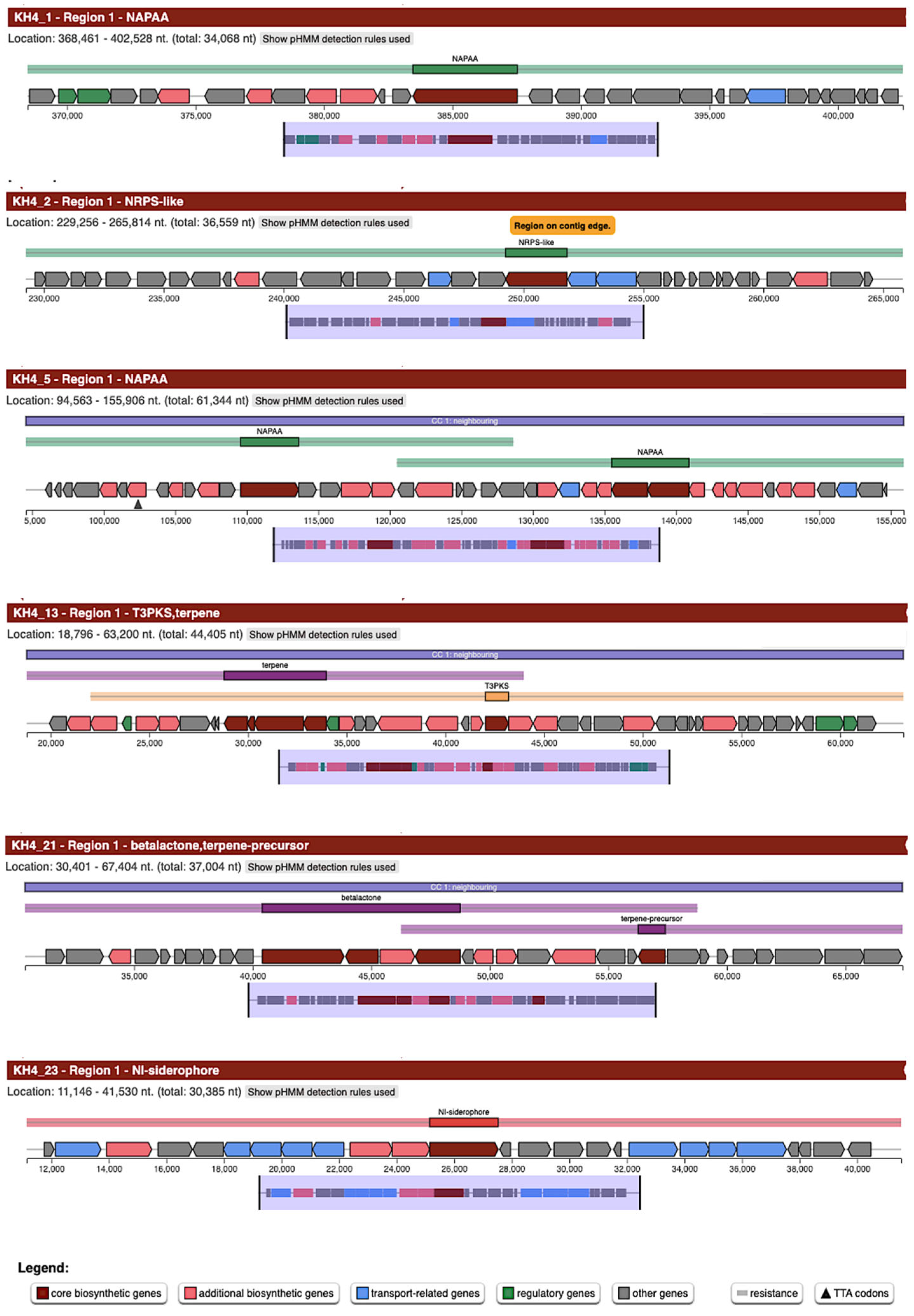

3.6. Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) in Kocuria spp.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.-J.; Jiang, Z.-M.; Zhi, X.-Y.; Chen, H.-H.; Yu, L.-Y.; Li, G.-F.; Zhang, Y.-Q. Genomic insights into Kocuria: Taxonomic revision and identification of five IAA-producing extremophiles. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1547983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stackebrandt, E.; Koch, C.; Gvodiak, O.; Schumann, P. Taxonomic Dissection of the Genus Micrococcus: Kocuria gen. nov., Nesterenkonia gen. nov., Kytococcus gen. nov., Dermacoccus gen. nov., and Micrococcus Cohn 1872 gen. emend. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1995, 45, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalević, B.; Jović, J.; Raičević, V.; Kljujev, I.; Kiković, D.; Hamidović, S. Biodegradation of methyl-tert-butyl ether by Kocuria sp. Hem. Ind. 2012, 66, 717–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.-K.; Wang, Y.; Lou, K.; Mao, P.-H.; Xu, L.-H.; Jiang, C.-L.; Kim, C.-J.; Li, W.-J. Kocuria halotolerans sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from a saline soil in China. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 1316–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kovács, G.; Burghardt, J.; Pradella, S.; Schumann, P.; Stackebrandt, E.; Márialigeti, K. Kocuria palustris sp. nov. and Kocuria rhizophila sp. nov., isolated from the rhizoplane of the narrow-leaved cattail (Typha angustifolia). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1999, 49, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.B.; Nedashkovskaya, O.I.; Mikhailov, V.V.; Han, S.K.; Kim, K.-O.; Rhee, M.-S.; Bae, K.S. Kocuria marina sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium isolated from marine sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2004, 54, 1617–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastager, S.G.; Tang, S.-K.; Srinivasan, K.; Lee, J.-C.; Li, W.-J. Kocuria indica sp. nov., isolated from a sediment sample. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Meng, L.; Xu, T.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Hong, S.; Huang, H.; et al. Kocuria dechangensis sp. nov., an actinobacterium isolated from saline and alkaline soils. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 3024–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Ponce, B.; Wang, D.; Soledad Vásquez-Murrieta, M.; Feng Chen, W.; Estrada-de los Santos, P.; Hua Sui, X.; Tao Wang, E. Kocuria arsenatis sp. nov., an arsenic-resistant endophytic actinobacterium associated with Prosopis laegivata grown on high-arsenic-polluted mine tailing. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziogou, A.; Giannakodimos, I.; Giannakodimos, A.; Baliou, S.; Ioannou, P. Kocuria Species Infections in Humans—A Narrative Review. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulameer, A.; Al-Rawi, D.F.; Al-Ani, M.Q. Production of keratinase enzyme from a local isolate of Kocuria rosea using environmental waste. Agric. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 16, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, A.; Sen, S.K.; Rajhans, G.; Raut, S. Purification and Optimization of Extracellular Lipase from a Novel Strain Kocuria flava Y4. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 2022, 6403090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Padilla, M.Y.; Gortáres-Moroyoqui, P.; Cira-Chávez, L.A.; Levasseur, A.; Dendooven, L.; Estrada-Alvarado, M.I. Characterization of extracellular amylase produced by haloalkalophilic strain Kocuria sp. HJ014. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2016, 26, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, G.L.d.P.A.; Vigoder, H.C.; Nascimento, J.n.d.S. Kocuria spp. in Foods: Biotechnological Uses and Risks for Food Safety. Appl. Food Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzair, B.; Menaa, F.; Khan, B.A.; Mohammad, F.V.; Ahmad, V.U.; Djeribi, R.; Menaa, B. Isolation, purification, structural elucidation and antimicrobial activities of kocumarin, a novel antibiotic isolated from actinobacterium Kocuria marina CMG S2 associated with the brown seaweed Pelvetia canaliculata. Microbiol. Res. 2018, 206, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, C.G.; Sujitha, P. Kocuran, an exopolysaccharide isolated from Kocuria rosea strain BS-1 and evaluation of its in vitro immunosuppression activities. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2014, 55, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bağcı, C.; Nuhamunada, M.; Goyat, H.; Ladanyi, C.; Sehnal, L.; Blin, K.; A Kautsar, S.; Tagirdzhanov, A.; Gurevich, A.; Mantri, S.; et al. BGC Atlas: A web resource for exploring the global chemical diversity encoded in bacterial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 53, D618–D624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juyal, K.; Devkar, H.; Deshpande, A.; Thakur, N.L. Genome assembly, analysis, and mining of Kocuria flava NIO_001: A thiopeptide antibiotic synthesizing bacterium isolated from marine sponge. Genome 2025, 68, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parshetti, G.K.; Parshetti, S.; Kalyani, D.C.; Doong, R.-a.; Govindwar, S.P. Industrial dye decolorizing lignin peroxidase from Kocuria rosea MTCC 1532. Ann. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, P.; Bagheriyeh, N.; Soltanian, H. Bioremediation potential of Kocuria rosea PH1 and Mesobacillus persicus DH1 for lead (Pb(II)) removal from contaminated environments. Bioremediation J. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achal, V.; Pan, X.; Zhang, D. Remediation of copper-contaminated soil by Kocuria flava CR1, based on microbially induced calcite precipitation. Ecol. Eng. 2011, 37, 1601–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaviparast, H.R.; Miranda, T.; Pereira, E.; Cristelo, N. A Comprehensive Review on Mine Tailings as a Raw Material in the Alkali Activation Process. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrina-Teatino, M.A.; Marquina-Araujo, J.J.; Avalos-Murga, J.A.; Carrion-Villacorta, F.L. Flotation of mine tailings: A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 116136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.P.; Coimbra, C.; Farias, P.; Francisco, R.; Branco, R.; Simão, F.V.; Gomes, E.; Pereira, A.; Vila, M.C.; Fiúza, A.; et al. Tailings microbial community profile and prediction of its functionality in basins of tungsten mine. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Mao, H.; Yang, X.; Zhao, W.; Sheng, L.; Sun, S.; Du, X. Resilience mechanisms of rhizosphere microorganisms in lead-zinc tailings: Metagenomic insights into heavy metal resistance. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 292, 117956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadd, G.M. Metals, minerals and microbes: Geomicrobiology and bioremediation. Microbiology 2010, 156, 609–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuaxinque-Flores, G.; Aguirre-Noyola, J.L.; Hernández-Flores, G.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Romero-Ramírez, Y.; Talavera-Mendoza, O. Bioimmobilization of toxic metals by precipitation of carbonates using Sporosarcina luteola: An in vitro study and application to sulfide-bearing tailings. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 724, 138124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talavera Mendoza, O.; Yta, M.; Moreno Tovar, R.; Dótor Almazán, A.; Flores Mundo, N.; Duarte Gutiérrez, C. Mineralogy and geochemistry of sulfide-bearing tailings from silver mines in the Taxco, Mexico area to evaluate their potential environmental impact. Geofísica Int. 2005, 44, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: Assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Moreira, B.; Vinuesa, P. GET_HOMOLOGUES, a Versatile Software Package for Scalable and Robust Microbial Pangenome Analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 7696–7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, A.M.; Esen, Ö.C.; Quince, C.; Vineis, J.H.; Morrison, H.G.; Sogin, M.L.; Delmont, T.O. Anvi’o: An advanced analysis and visualization platform for ‘omics data. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinuesa, P.; Ochoa-Sánchez, L.E.; Contreras-Moreira, B. GET_PHYLOMARKERS, a Software Package to Select Optimal Orthologous Clusters for Phylogenomics and Inferring Pan-Genome Phylogenies, Used for a Critical Geno-Taxonomic Revision of the Genus Stenotrophomonas. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, L.; Glover, R.H.; Humphris, S.; Elphinstone, J.G.; Toth, I.K. Genomics and taxonomy in diagnostics for food security: Soft-rotting enterobacterial plant pathogens. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuchcinski, K.; Dziurzynski, M. Fast and accurate detection of metal resistance genes using MetHMMDb. bioRxiv 2025. bioRxiv:2024.2012.2026.629440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, C.; Laird, M.R.; Williams, K.P.; Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group; Lau, B.Y.; Hoad, G.; Winsor, G.L.; Brinkman, F.S. IslandViewer 4: Expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W30–W35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Vader, L.; Szenei, J.; Reitz, Z.L.; E Augustijn, H.; Cediel-Becerra, J.D.D.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; A Koetsier, R.; E Williams, S.; et al. antiSMASH 8.0: Extended gene cluster detection capabilities and analyses of chemistry, enzymology, and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W32–W38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Muñoz, J.C.; Selem-Mojica, N.; Mullowney, M.W.; Kautsar, S.A.; Tryon, J.H.; Parkinson, E.I.; De Los Santos, E.L.C.; Yeong, M.; Cruz-Morales, P.; Abubucker, S.; et al. A computational framework to explore large-scale biosynthetic diversity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2020, 16, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansda, A.; Kumar, V.; Anshumali. Cu-resistant Kocuria sp. CRB15: A potential PGPR isolated from the dry tailing of Rakha copper mine. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, S.; Menaa, B.; Chekireb, D. Screening of heavy metal-resistant rhizobial and non-rhizobial microflora isolated from Trifolium sp. growing in mining areas. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Nan, J. Comparative Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Provides New Insights into the Aflatoxin B1 Biodegradability by Kocuria rosea from Deep Sea. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Oren, A.; Ventosa, A.; Christensen, H.; Arahal, D.R.; da Costa, M.S.; Rooney, A.P.; Yi, H.; Xu, X.-W.; De Meyer, S.; et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Sun, R.-Q.; Zeng, J.-H.; Wei, H.-M.; Shen, B.; Sun, J.-Q. Multiple-omics analysis of three novel haloalkaliphilic species of Kocuria revealed that the phenolic acid-degrading abilities are ubiquitous in the genus. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1626161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, C.C.; Vidal, L.; Salazar, V.; Swings, J.; Thompson, F.L. Microbial Genomic Taxonomy. Trends Syst. Bact. Fungi 2021, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Wu, B.; Zheng, Q.; Long, Y.; Jiang, J.; Hu, X. Long-abandoned mining environments reshape soil microbial co-occurrence patterns, community assembly, and biogeochemistry. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 213, 106254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xiang, G.; Xiao, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, B. Microbial mediated remediation of heavy metals toxicity: Mechanisms and future prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1420408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zacaria Vital, T.; Román-Ponce, B.; Rivera Orduña, F.N.; Estrada de los Santos, P.; Vásquez-Murrieta, M.S.; Deng, Y.; Yuan, H.L.; Wang, E.T. An endophytic Kocuria palustris strain harboring multiple arsenate reductase genes. Arch. Microbiol. 2019, 201, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Diwan, B. Bacterial Exopolysaccharide mediated heavy metal removal: A Review on biosynthesis, mechanism and remediation strategies. Biotechnol. Rep. 2017, 13, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dong, F.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, F.; Lv, Z.; Xue, J.; He, D. Biosorption and biomineralization of U(VI) by Kocuria rosea: Involvement of phosphorus and formation of U–P minerals. Chemosphere 2022, 288, 132659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- François, F.; Lombard, C.; Guigner, J.-M.; Soreau, P.; Brian-Jaisson, F.; Martino, G.; Vandervennet, M.; Garcia, D.; Molinier, A.-L.; Pignol, D.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Environmental Bacteria Capable of Extracellular Biosorption of Mercury. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 1097–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, P.R.; Suresh, K.; Jiang, G. Bacterial bioremediation of heavy metals in wastewater: A review of processes and applications. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 48, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, M.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, D.K. Multimetal tolerance mechanisms in bacteria: The resistance strategies acquired by bacteria that can be exploited to ‘clean-up’ heavy metal contaminants from water. Aquat. Toxicol. 2019, 212, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, F.; Butt, M.; Ali, H.; Chaudhary, H.J. Biosorption of cadmium and chromium from water by endophytic Kocuria rhizophila: Equilibrium and kinetic studies. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 19946–19958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulik, A.R.; Bhadekar, R.K. Heavy metal removal by bacterial isolates from the antarctic oceanic region. Int. J. Pharma Bio Sci. 2017, 8, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, G.E.; Ho, S.F.S.; Cummins, E.A.; Wildsmith, A.J.; McInnes, R.S.; Weigel, C.; Tong, L.Y.S.; Quick, J.; van Schaik, W.; Moran, R.A. The Kocurious case of Noodlococcus: Genomic insights into Kocuria rhizophila from characterisation of a laboratory contaminant. Microb. Genom. 2025, 11, 001526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokuda, M.; Shintani, M. Microbial evolution through horizontal gene transfer by mobile genetic elements. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.F.R.; Sousa, E.; Resende, D.I.S.P. A Practical Toolkit for the Detection, Isolation, Quantification, and Characterization of Siderophores and Metallophores in Microorganisms. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 26863–26877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Siyabi, N.; Al-Ansari, A.; Abri, M.A.A.; Sivakumar, N. Genomic insights into biosynthetic gene cluster diversity and structural variability in marine bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacovelli, R.; Bovenberg, R.A.L.; Driessen, A.J.M. Nonribosomal peptide synthetases and their biotechnological potential in Penicillium rubens. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 48, kuab045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaki, H.; Tamura, T.; Igarashi, Y. Taxonomic Positions and Secondary Metabolite-Biosynthetic Gene Clusters of Akazaoxime- and Levantilide-Producers. Life 2023, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christinaki, A.C.; Myridakis, A.I.; Kouvelis, V.N. Genomic insights into the evolution and adaptation of secondary metabolite gene clusters in fungicolous species Cladobotryum mycophilum ATHUM6906. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genet. 2024, 14, jkae006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helfrich, E.J.N.; Lin, G.-M.; Voigt, C.A.; Clardy, J. Bacterial terpene biosynthesis: Challenges and opportunities for pathway engineering. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 2889–2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, B.; Wei, X.; Wan, C.; Zhao, W.; Song, R.; Xin, S.; Song, K. Exploring the Biological Pathways of Siderophores and Their Multidisciplinary Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2024, 29, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Mora, D.J.; Flores-Dávalos, A.G.; Lorenzo-Santiago, M.A.; Guardado-Fierros, B.G.; Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Contreras-Ramos, S.M. Maximizing Biomass Production and Carotenoid-like Pigments Yield in Kocuria sediminis As04 Through Culture Optimization. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, J.; Da, S.; Sousa, T.; Crespo, G.; Palomo, S.; González, I.; Tormo, J.R.; De la Cruz, M.; Anderson, M.; Hill, R.T.; et al. Kocurin, the True Structure of PM181104, an Anti-Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Thiazolyl Peptide from the Marine-Derived Bacterium Kocuria palustris. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.U.; Harunari, E.; Sharma, A.R.; Oku, N.; Akasaka, K.; Urabe, D.; Sibero, M.T.; Igarashi, Y. Nocarimidazoles C and D, antimicrobial alkanoylimidazoles from a coral-derived actinomycete Kocuria sp.: Application of 1JC,H coupling constants for the unequivocal determination of substituted imidazoles and stereochemical diversity of anteisoalkyl chains in microbial metabolites. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 2719–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Haferburg, G.; Sineriz, M.; Merten, D.; Büchel, G.; Kothe, E. Heavy metal resistance mechanisms in actinobacteria for survival in AMD contaminated soils. Geochemistry 2005, 65, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannabiran, K. Actinobacteria are better bioremediating agents for removal of toxic heavy metals: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2017, 20, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankar, A.; Nagaraja, G. Chapter 18—Recent Trends in Biosorption of Heavy Metals by Actinobacteria. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Singh, B.P., Gupta, V.K., Passari, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Qiu, Z.; Tan, H.; Cao, L. Siderophore production by actinobacteria. BioMetals 2014, 27, 623–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | BGC Class |

|---|---|

| Kocuria sp. KH4 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria aegyptia JCM 14735 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria arenosa CPCC 205293 | NAPAA; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria atrinae JCM 15914 | NAPAA; RiPP-like; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria carniphila CCM 132 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria cellulosilytica CPCC 205292 | NAPAA; NRPS-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria coralli SCSIO 13007 | NI-siderophore; T3PKS; betalactone; terpene; terpene-precursor |

| Kocuria dechangesis CGMCC 1.12187 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria flava HO-9041 1 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; azole-containing-RiPP; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria gwangalliensis JCM 18958 | NAPAA; RiPP-like; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria kalidii M4R5S9 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria marina KCTC 9943 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria massiliensis Marseille-P3598 2 | NI-siderophore; RiPP-like; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria nitroreducens CPCC 205315 | NAPAA; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria oceani FXJ8.057 23 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria oxytropis CPCC 205268 | NAPAA; NRPS-like; betalactone; linaridin; T3PKS.terpene; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria palustris TAGA27 | NI-siderophore; terpene; terpene-precursor |

| Kocuria rhizophila NBC 01227 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; RiPP-like; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria rhizosphaerae M1R5S2 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria rhizosphaericola M4R2S49 | NAPAA; NRPS-like; betalactone; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor |

| Kocuria rosea S-A3 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria sabuli CPCC 205300 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; RiPP-like; T3PKS; T3PKS.terpene; indole; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria salsicia JCM 16361 | NAPAA; NRPS.NRP-metallophore; RiPP-like; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria sediminis JCM 17929 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria soli M5W7-7 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; hglE-KS; terpene; terpene-precursor |

| Kocuria subflava YIM 13062 | NAPAA; terpene; terpene-precursor |

| Kocuria turfanensis HO-9042 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; NRPS-like; T3PKS.terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria tytonicola 473 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria tytonis 442 | NAPAA; NI-siderophore; RiPP-like; T3PKS; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

| Kocuria varians NBRC 15358 | NAPAA; NRPS.NRP-metallophore; RiPP-like; terpene; terpene-precursor.betalactone |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cuaxinque-Flores, G.; Gómez-Godínez, L.J.; Armenta-Medina, A.; Zelaya-Molina, L.X.; Ramos-Garza, J.; Aguirre-Noyola, J.L. Genome Insights into Kocuria sp. KH4, a Metallophilic Bacterium Harboring Multiple Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs). Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120255

Cuaxinque-Flores G, Gómez-Godínez LJ, Armenta-Medina A, Zelaya-Molina LX, Ramos-Garza J, Aguirre-Noyola JL. Genome Insights into Kocuria sp. KH4, a Metallophilic Bacterium Harboring Multiple Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs). Microbiology Research. 2025; 16(12):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120255

Chicago/Turabian StyleCuaxinque-Flores, Gustavo, Lorena Jacqueline Gómez-Godínez, Alma Armenta-Medina, Lily X. Zelaya-Molina, Juan Ramos-Garza, and José Luis Aguirre-Noyola. 2025. "Genome Insights into Kocuria sp. KH4, a Metallophilic Bacterium Harboring Multiple Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)" Microbiology Research 16, no. 12: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120255

APA StyleCuaxinque-Flores, G., Gómez-Godínez, L. J., Armenta-Medina, A., Zelaya-Molina, L. X., Ramos-Garza, J., & Aguirre-Noyola, J. L. (2025). Genome Insights into Kocuria sp. KH4, a Metallophilic Bacterium Harboring Multiple Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs). Microbiology Research, 16(12), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres16120255