Effect of Buffer Room Configuration on Isolation of Bacteriophage phi6 and Micrococcus Luteus Emissions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Layout of the Tested Rooms

2.2. Test Apparatus

2.3. Test Procedures

- Determining the effectiveness of airlock prototype I assembled as a single-chamber airlock with passage time of 30 s (the basic variant);

- Determining the effectiveness of airlock prototype I as double-chamber airlock with passage time 30 s;

- Determining the effectiveness of airlock prototype I assembled as a single-chamber airlock with passage time of 5 s;

- Determining the effectiveness of airlock prototype I assembled as a single-chamber airlock with passage time of 120 s.

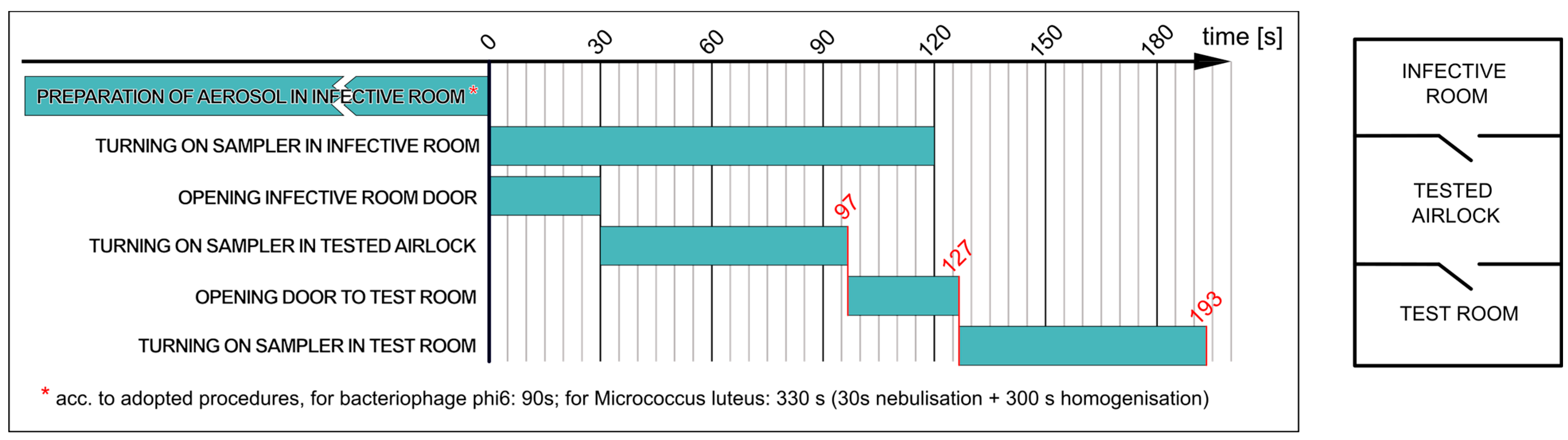

2.3.1. Determining Effectiveness of Airlock Prototype I Assembled as Single-Chamber Airlock with Passage Time of 30 s (Variant a)

- ▪

- The nebulisation of the M. luteus suspension in the infective room for 30 s, followed by bioaerosol homogenisation for 5 min;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the infective room and simultaneously opening the door to the airlock for 30 s;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the airlock and then opening the door to the test room for 30 s;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air in the test room.

- ▪

- The nebulisation of the phi6 suspension in the infective room for 90 s (without homogenisation—without switching on fans in the infective room);

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the infective room and simultaneously opening the door to the airlock for 30 s;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the airlock and then opening the door to the test room for 30 s;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air in the test room.

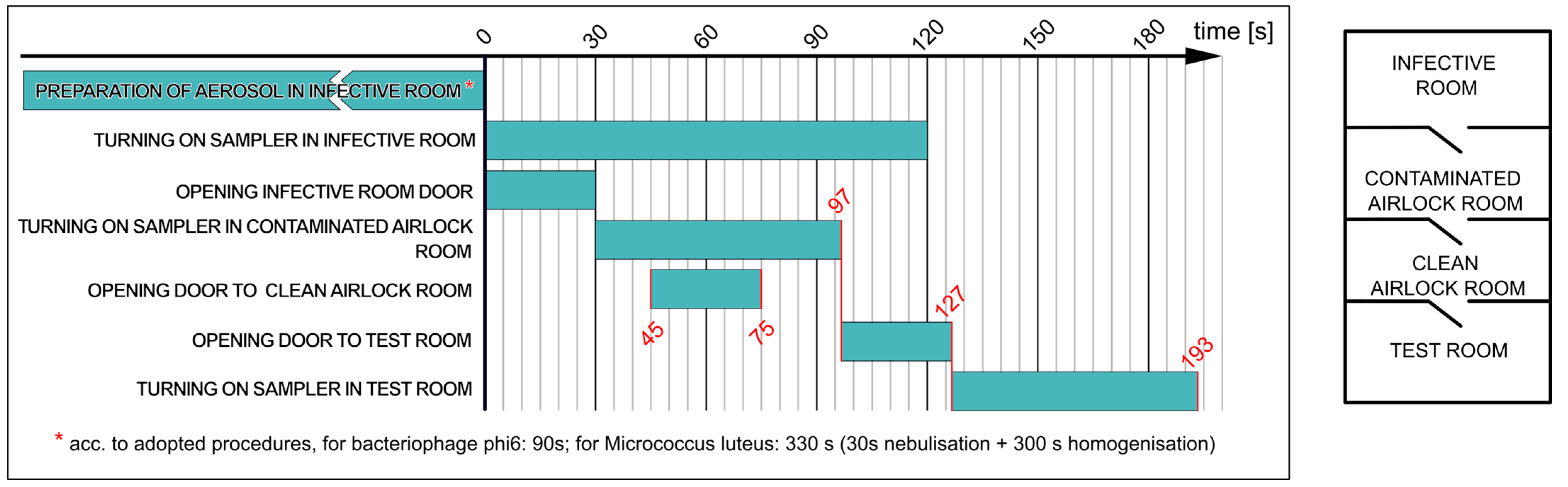

2.3.2. Determining Effectiveness of Airlock Prototype I Assembled as Double-Chamber Airlock with Passage Time of 30 s (Variant b)

- ▪

- The nebulisation of the M. luteus suspension in the infective room for 30 s, followed by bioaerosol homogenisation for 5 min;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the infective room and simultaneously opening the door to the airlock for 30 s;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the contaminated room and then opening the door to the clean room for 30 s;

- ▪

- Passage to the airlock; then opening the door to the test room;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air in the test room.

- ▪

- The nebulisation of the phage suspension in the infective room for 90 s (without homogenisation);

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the infective room and simultaneously opening the door to the contaminated room for 30 s;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air from the contaminated room and then opening the door to the clean room for 30 s;

- ▪

- Passage to the airlock; then opening the door to the test room;

- ▪

- Collecting 200 L of air in the test room.

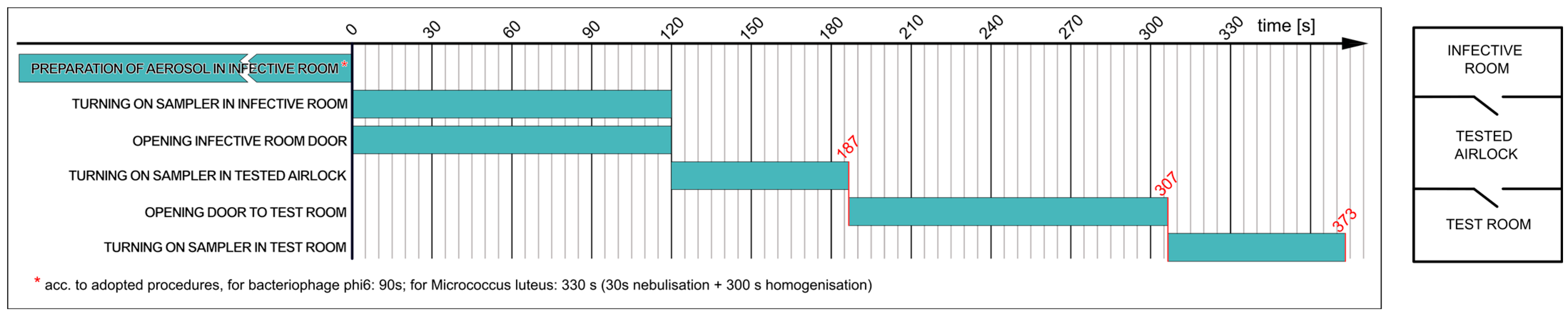

2.3.3. Determining Effectiveness of Airlock Prototype I Assembled as Single-Chamber Airlock Depending on Time of Passage through Door (Variants c and d)

3. Results

3.1. Determining Effectiveness of Airlock Prototype I Assembled as Single-Chamber Airlock

3.2. Determining Effectiveness of Airlock Prototype I Assembled as Double-Chamber Airlock in Laboratory Conditions

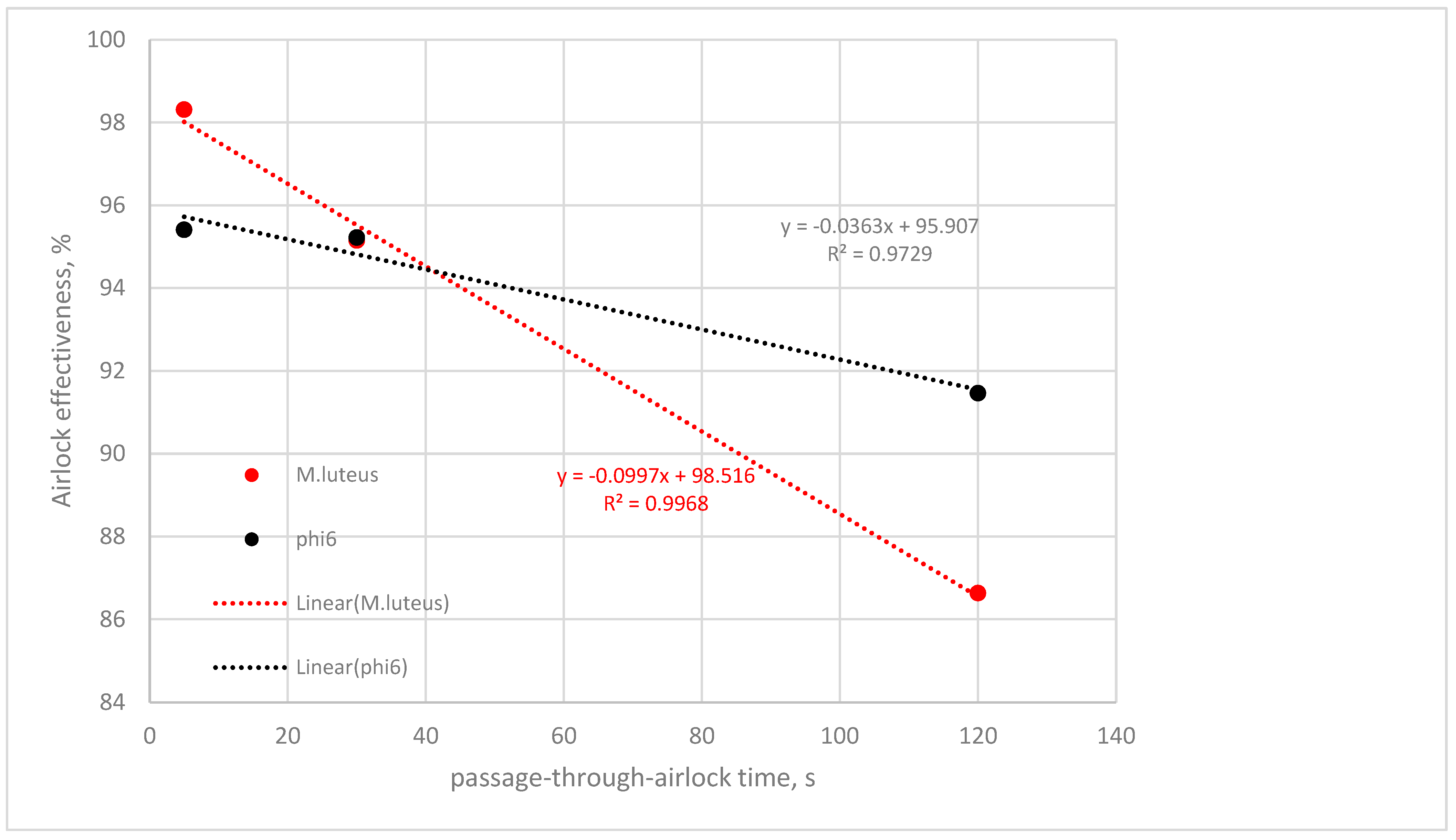

3.3. Determining Effectiveness of Airlock Prototype I Assembled as Single-Chamber Airlock, Depending on Passage-through-Airlock Time

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Priolo Filho, S.R.; Chae, H.; Bhakta, A.; Moura, B.R.; Correia, B.B.; da Silva Santos, J.; Sieben, T.L.; Goldfarb, D. A qualitative analysis of child protection professionals’ challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child. Abuse Negl. 2023, 143, 106229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, J.A.; Lima, E.M.; Coelho, K.S.; Behrens, J.H.; Landgraf, M.; Franco, B.D.; Pinto, U.M. Adherence to food hygiene and personal protection recommendations for prevention of COVID-19. In Trends in Food Science and Technology; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 112, pp. 847–852. [Google Scholar]

- Herselman, R.; Lalloo, V.; Ueckermann, V.; van Tonder, D.J.; de Jager, E.; Spijkerman, S.; Van der Merwe, W.; Du Pisane, M.; Hattingh, F.; Stanton, D.; et al. Adapted full-face snorkel masks as an alternative for COVID-19 personal protection during aerosol generating procedures in South Africa: A multi-centre, non-blinded in-situ simulation study. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 11, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, C.; Glucklich, T.; Attrash-Najjar, A.; Jacobson, M.A.; Cohen, N.; Varela, N.; Priolo-Filho, S.R.; Bérubé, A.; Chang, O.D.; Collin-Vézina, D.; et al. The global impact of COVID-19 on child protection professionals: A scoping review and thematic analysis. Child. Abus. Negl. 2023, 106347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E.C.; Zagrodney, K.A.P.; McKay, S.M.; Holness, D.L.; Nichol, K.A. Determinants of nurse’s and personal support worker’s adherence to facial protective equipment in a community setting during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ontario, Canada: A pilot study. Am. J. Infect. Control 2023, 51, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettari, L.; Pero, G.; Maiandi, C.; Messina, A.; Saccocci, M.; Cirillo, M.; Troise, G.; Conti, E.; Cuccia, C.; Maffeo, D. Exploring Personal Protection During High-Risk PCI in a COVID-19 Patient. JACC Case Rep. 2020, 2, 1279–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Kloka, J.; Lotz, G.; Zacharowski, K.; Raimann, F.J. The Frankfurt COVid aErosol pRotEction Dome–COVERED–a consideration for personal protective equipment improvement and technical note. In Anaesthesia Critical Care and Pain Medicine; Elsevier Masson SAS: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 39, pp. 373–374. [Google Scholar]

- Abkar, L.; Zimmermann, K.; Dixit, F.; Kheyrandish, A.; Mohseni, M. COVID-19 pandemic lesson learned-critical parameters and research needs for UVC inactivation of viral aerosols. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 8, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathore, R.; Gupta, A.; Bherwani, H.; Labhasetwar, N. Understanding air and water borne transmission and survival of coronavirus: Insights and way forward for SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 141486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gu, J.; An, T. The emission and dynamics of droplets from human expiratory activities and COVID-19 transmission in public transport system: A review. Build. Environ. 2022, 219, 109224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Xu, B.; Gamal El-Din, M. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 via fecal-oral and aerosols–borne routes: Environmental dynamics and implications for wastewater management in underprivileged societies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 743, 140709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Xie, L.; Xiao, Y. Documentary Research of Human Respiratory Droplet Characteristics. In Procedia Engineering; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 1365–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, P.M.; Stamenic, D.; Gajewska, K.; O’Sullivan, M.B.; Doyle, S.; O’Reilly, O.; Buckley, C.M. Cross-sectional survey of compliance behaviour, knowledge and attitudes among cases and close contacts during COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Pract. 2023, 5, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.M.; Brosseau, L.M. Aerosol transmission of infectious disease. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2015, 57, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eames, I.; Tang, J.W.; Li, Y.; Wilson, P. Airborne transmission of disease in hospitals. J. R. Soc. Interface 2009, 6, S697–S702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, X.; Weerasuriya, A.U.; Hang, J.; Zeng, L.; Luo, Q.; Li, C.Y.; Chen, Z. Numerical investigation of the effects of environmental conditions, droplet size, and social distancing on droplet transmission in a street canyon. Build. Environ. 2022, 221, 109261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, S.; Niwalkar, A.; Gupta, A.; Gautam, S.; Anshul, A.; Bherwani, H.; Biniwale, R.; Kumar, R. Is safe distance enough to prevent COVID-19? Dispersion and tracking of aerosols in various artificial ventilation conditions using OpenFOAM. Gondwana Res. 2023, 114, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled Ahmed, S.; Mohammed Ali, R.; Maha Lashin, M.; Fayroz Sherif, F. Designing a new fast solution to control isolation rooms in hospitals depending on artificial intelligence decision. Biomed. Signal Process Control 2023, 79, 104100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z.; He, J.; Hu, C.; Rong, R.; Han, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, D. Reducing airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by an upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation system in a hospital isolation environment. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravia, S.A.; Raynor, P.C.; Streifel, A.J. A performance assessment of airborne infection isolation rooms. Am. J. Infect. Control 2007, 35, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Dey, K.; Paul, A.R.; Biswas, R. A novel CFD analysis to minimize the spread of COVID-19 virus in hospital isolation room. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, O.; Li, A.; Olofsson, T.; Zhang, L.; Lei, W. Adaptive Wall-Based Attachment Ventilation: A Comparative Study on Its Effectiveness in Airborne Infection Isolation Rooms with Negative Pressure. Engineering 2022, 8, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalliomäki, P.; Hagström, K.; Itkonen, H.; Grönvall, I.; Koskela, H. Effectiveness of directional airflow in reducing containment failures in hospital isolation rooms generated by door opening. Build. Environ. 2019, 158, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.K.; Chuang, H.H.; Hsiao, T.C.; Chuang, H.C.; Chen, P.C. Investigating the invisible threat: An exploration of air exchange rates and ultrafine particle dynamics in hospital operating rooms. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, R.; Andrych-Zalewska, M.; Matla, J.; Molska, J.; Sierzputowski, G.; Szulak, A.; Włostowski, R.; Włóka, A.; Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M. Assessment of the Possibility of Using Bacterial Strains and Bacteriophages for Epidemiological Studies in the Bioaerosol Environment. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierzputowski, G.; Piechota, N.; Krajewski, T.; Szewc, M. Patent application No P442153 (30 August 2022) “Adaptive Geometric Dimensions Mobile Buffer Space” (Szczegóły PAT—P.442153). Available online: https://uprp.gov.pl/pl (accessed on 3 June 2024).

| Bacterium | Bacteriophage | |

|---|---|---|

| Kind | Micrococcus luteus ATCC 7468 | phage phi6 |

| Control samples | bacterial strain streak inoculation | host strain streak inoculation |

| surface inoculation of stabilised suspension before nebulisation | surface inoculation of phage before nebulisation | |

| surface inoculation of stabilised suspension after nebulisation | surface inoculation of phage suspension after nebulisation | |

| Samples of air in test room | after disinfection | after disinfection |

| after nebulisation | after nebulisation |

| Kind of Bioaerosol | Effectiveness without Airlock, %R | Effectiveness with Airlock, %R |

|---|---|---|

| M. luteus | 77.27% (N = 8; SD = 10%) | 95.15% (N = 8; SD = 2.2%) |

| phage phi6 | 72.48% (N = 6; SD = 26.3%) | 95.22% (N = 8; SD = 3.9%) |

| Kind of Bioaerosol | Effectiveness without Airlock, %R | Effectiveness with Airlock, %R |

|---|---|---|

| M. luteus | 85.94% (N = 7; SD = 3.2%) | 98.17% (N = 7; SD = 1%) |

| phage phi6 | 82.99% (N = 8; SD = 8.3%) | 98.37% (N = 8; SD = 2%) |

| Kind of Bioaerosol | Passage-through-Airlock Time | Effectiveness without Airlock, %R | Effectiveness with Airlock, %R |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. luteus | 5 s | 86.32% (N = 8; SD = 7.1%) | 98.31% (N = 8; SD = 0.9%) |

| 30 s | 77.27% (N = 8; SD = 10%) | 95.15% (N = 8; SD = 2.2%) | |

| 120 s | 59.25% (N = 6; SD = 17.5%) | 86.63% (N = 6; SD = 4%) | |

| phage phi6 | 5 s | 67.75% (N = 6; SD = 23.5%) | 95.41% (N = 6; SD = 3.1%) |

| 30 s | 72.48% (N = 6; SD = 26.3%) | 95.22% (N = 8; SD = 3.9%) | |

| 120 s | 65.69% (N = 3; SD = 38.7%) | 91.46% (N = 3; SD = 10.1%) |

| Version | M. luteus ATCC 7468 | Phage phi6 |

|---|---|---|

| Single-chamber version, passage time 30 s | 95.15% | 95.22% |

| Double-chamber version, passage time 30 s | 98.17% | 98.37% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wróbel, R.; Andrych-Zalewska, M.; Matla, J.; Molska, J.; Sierzputowski, G.; Szulak, A.; Włostowski, R.; Włóka, A.; Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M. Effect of Buffer Room Configuration on Isolation of Bacteriophage phi6 and Micrococcus Luteus Emissions. Microbiol. Res. 2024, 15, 1099-1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030073

Wróbel R, Andrych-Zalewska M, Matla J, Molska J, Sierzputowski G, Szulak A, Włostowski R, Włóka A, Rutkowska-Gorczyca M. Effect of Buffer Room Configuration on Isolation of Bacteriophage phi6 and Micrococcus Luteus Emissions. Microbiology Research. 2024; 15(3):1099-1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030073

Chicago/Turabian StyleWróbel, Radosław, Monika Andrych-Zalewska, Jędrzej Matla, Justyna Molska, Gustaw Sierzputowski, Agnieszka Szulak, Radosław Włostowski, Adriana Włóka, and Małgorzata Rutkowska-Gorczyca. 2024. "Effect of Buffer Room Configuration on Isolation of Bacteriophage phi6 and Micrococcus Luteus Emissions" Microbiology Research 15, no. 3: 1099-1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030073

APA StyleWróbel, R., Andrych-Zalewska, M., Matla, J., Molska, J., Sierzputowski, G., Szulak, A., Włostowski, R., Włóka, A., & Rutkowska-Gorczyca, M. (2024). Effect of Buffer Room Configuration on Isolation of Bacteriophage phi6 and Micrococcus Luteus Emissions. Microbiology Research, 15(3), 1099-1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/microbiolres15030073