1. Introduction

1.1. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is defined by the presence of hepatic steatosis detected either through imaging or biopsy, along with at least one of the following five cardiometabolic risk factors: (1) body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m

2 (≥23 kg/m

2 in Asians) or waist circumference >94 cm in men, >80 cm in women, or adjusted for ethnicity; (2) fasting serum glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL (≥5.6 mmol/L) or 2-h post-load glucose level ≥ 140 mg/dL (≥7.8 mmol/L) or HbA1c ≥ 5.7% or on specific drug treatment; (3) blood pressure ≥ 130/85 mmHg or specific drug treatment; (4) plasma triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL (≥1.70 mmol/L) or specific drug treatment; (5) plasma HDL cholesterol < 40 mg/dL (<1.0 mmol/L) for men and <50 mg/dL (<1.3 mmol/L) for women or specific drug treatment [

1,

2,

3,

4]. MASLD affects nearly 25–30% of the global adult population and has shown a notable increase in prevalence over recent decades [

5,

6].

MASLD pathogenesis involves a complex interplay of factors, including insulin resistance, oxidative stress, inflammation, and lipotoxicity. Insulin resistance leads to increased hepatic lipid accumulation, while oxidative stress and inflammation contribute to hepatocyte injury and fibrosis. These processes can progress to more severe forms of liver disease, such as metabolic-dysfunction associated steatohepatitis (MASH), cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Clinical implications of MASLD are significant. MASLD is a major global health concern with increasing prevalence due to the rising rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Indeed, MASLD is frequently associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Furthermore individuals with MASLD show high cardiovascular specific mortality rate (4.79 per 1000 person-years) and liver-specific mortality (0.77 per 1000 person-years) [

7]. Besides, MASLD is one of the main causes of HCC, being responsible for 1–38% of HCC’s cases globally, even in the absence of cirrhosis [

8,

9]. It is noteworthy that, despite the clinical burden associated with MASLD, it represents primarily an insidious and asymptomatic disease, notably in the early stages. On the other side, MASLD is a potentially reversible disease and prompt lifestyle, medical and bariatric interventions could frequently improve liver conditions [

10]. Liver biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing liver steatosis, as it allows for grading steatosis and staging fibrosis in the histological sample. However, its invasiveness, limited patient acceptability, sampling variability and high cost make it unsuitable for routine clinical practice. For this reason, the development of non-invasive techniques for the early diagnosis of MASLD and the subsequent assessment of the response to the interventions is crucial.

1.2. Ultrasound Evaluation and Quantification of Liver Fat Content

Conventional ultrasonography (US) is the most commonly used imaging method for diagnosing hepatic steatosis due to its widespread availability, established use, good tolerability, and low cost. Hepatic steatosis is typically graded as normal (grade 0), mild (grade 1), moderate (grade 2) or severe (grade 3) [

11].

Mild steatosis is defined by a minimal increase in liver echogenicity compared to right kidney parenchyma. Moderate steatosis is characterized by posterior beam attenuation limited to posterior segments of the right hepatic lobe. Severe steatosis involves posterior beam attenuation severe enough to impair the diaphragm visualization, accompanied by blurring of intrahepatic vessels [

12]. Qualitative hepatic steatosis assessment performed by experienced operator has demonstrated a good sensitivity and specificity [

13]. However, grading steatosis via US remains challenging due to the subjective nature of visual assessment of fatty infiltration. Furthermore, the accuracy of US in diagnosing liver steatosis is reduced in patients with obesity and coexistent renal disease [

14,

15]. Besides that, qualitative US assessment of liver steatosis is less reliable in follow-up, lacking of an objective and reproducible measurement to assess improvement or worsening of the condition.

Among non-invasive alternatives, magnetic resonance imaging-based proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) is an accurate and reproducible method for quantifying liver fat and has been used as a reference standard in numerous clinical trials [

16,

17]. Despite its precision, MRI-PDFF lacks cost-effectiveness for widespread clinical use. In this context, recent studies have demonstrated promising results for detecting and grading hepatic steatosis using US and quantitative ultrasound (QUS), which combine non-invasiveness, broad availability, and cost-effectiveness [

18,

19]. Fat deposition alters ultrasound signals in three key ways: amplitude, frequency variation, and signal scattering. The brightness information in US images reflects a combination of these properties. Several methods have been introduced to quantify these changes and improve the diagnosis of fatty liver. One of these tools is the echogenicity ratio of the liver compared to the kidney, namely hepato-renal index (HRI). HRI has shown significant correlation with histologic steatosis. Studies have reported that HRI is highly accurate (>90%) for detecting hepatic steatosis and correlates strongly with MRI-PDFF in patients without advanced liver fibrosis [

20]. Currently, several US manufacturers offer automated HRI calculation tools. In particular, Samsung offers as a quantification tool for fatty liver the EzHRI function which improves workflow by suggesting initial ROI (region of interest) positions. Moreover, other techniques used in clinical studies estimate the attenuation coefficient (AC) and the backscatter coefficient (BSC). The AC measures the loss of US energy in tissue, whereas the BSC measures the US energy reflected from tissue, which relates to tissue microstructure [

21]. Samsung has integrated these methods into their US systems, proving tools like TAI (Tissue Attenuation Imaging) and TSI (Tissue Scatter Imaging). TAI quantitatively measures the attenuation of ultrasound signals received from the liver. TSI quantifies the scattered signal distribution based on backscattered signals. The combination of AC and BSC allows for the calculation of the ultrasound fat fraction (USFF), a quantitative US-based method for estimating liver fat content [

22]. Several studies have shown strong agreement between USFF and MRI-PDFF measurement for quantifying liver fat content, highlighting its potential clinical utility in enhancing the diagnostic value of US for hepatic steatosis [

23,

24]. Despite this advancement, there is limited data regarding the clinical use of USFF, and threshold for different grades of steatosis remains undefined. Nonetheless, none of the previous study investigating the diagnostic value of the USFF, focused on the subset of obese patients, which is a major risk for evolution from MASLD to liver cirrhosis [

25]. Additionally, due to the technical challenge to perform a good quality imaging in obese patients, a reliable non-invasive standard measurement of liver steatosis could be crucial [

26].

The aim of this study is to evaluate for the first time the potential role of artificial intelligence (AI)-implemented USFF in grading steatosis in clinical practice in patients with moderate to morbid obesity.

2. Materials and Methods

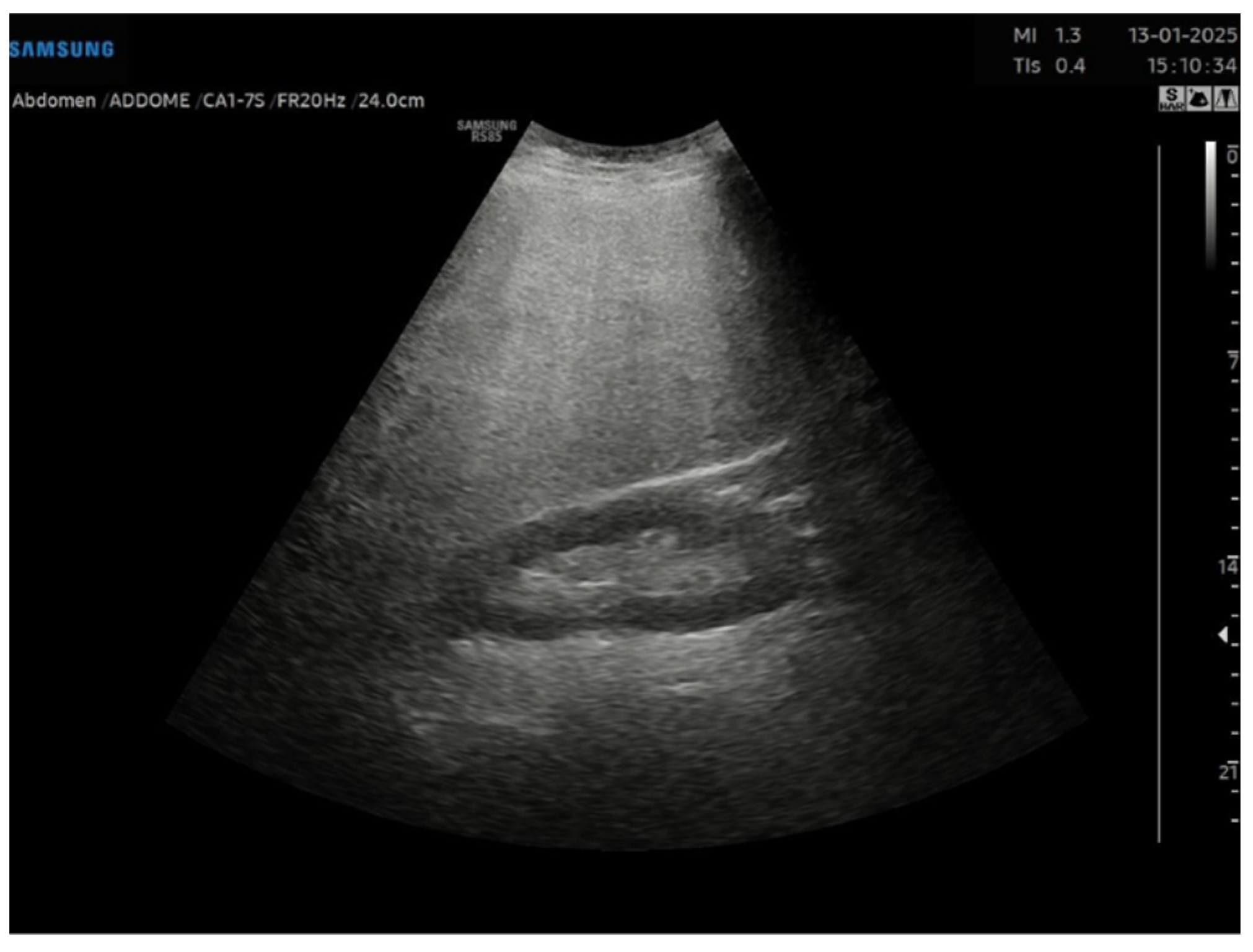

This is a cross-sectional observational study based on retrospectively collected ultrasound and clinical data. A total of 95 obese patients who underwent abdominal ultrasound examination as part of the preoperative assessment for potential bariatric surgery between November 2023 and April 2024 were evaluated. Ultrasound examinations were performed by expert echographers (with a minimum of 5 years’ experience in abdominal US) using Samsung RS85 Prestige system. The examination was performed after at least 6 h of fasting, with the patient in the supine position, using a right intercostal scanning approach. Each patient underwent conventional abdomen ultrasound with visual assessment of liver steatosis (

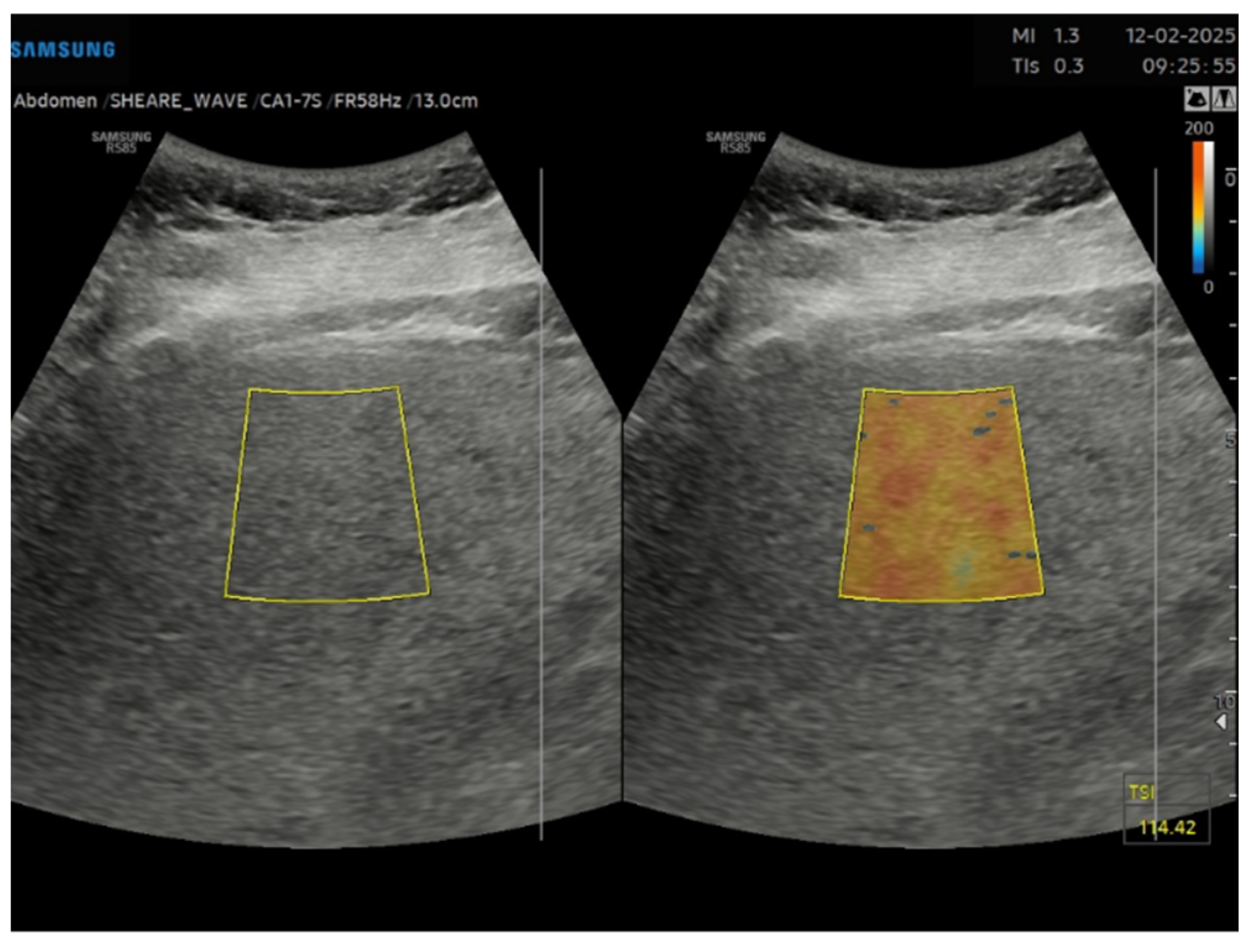

Figure 1) and subsequently to the measurement of USFF with the Samsung CA1–7S (1 MHz–7 MHz) transducer. The ultrasonographic steatosis visual assessment and the USFF measurement were performed by different groups of operators in a blinded manner. TSI (

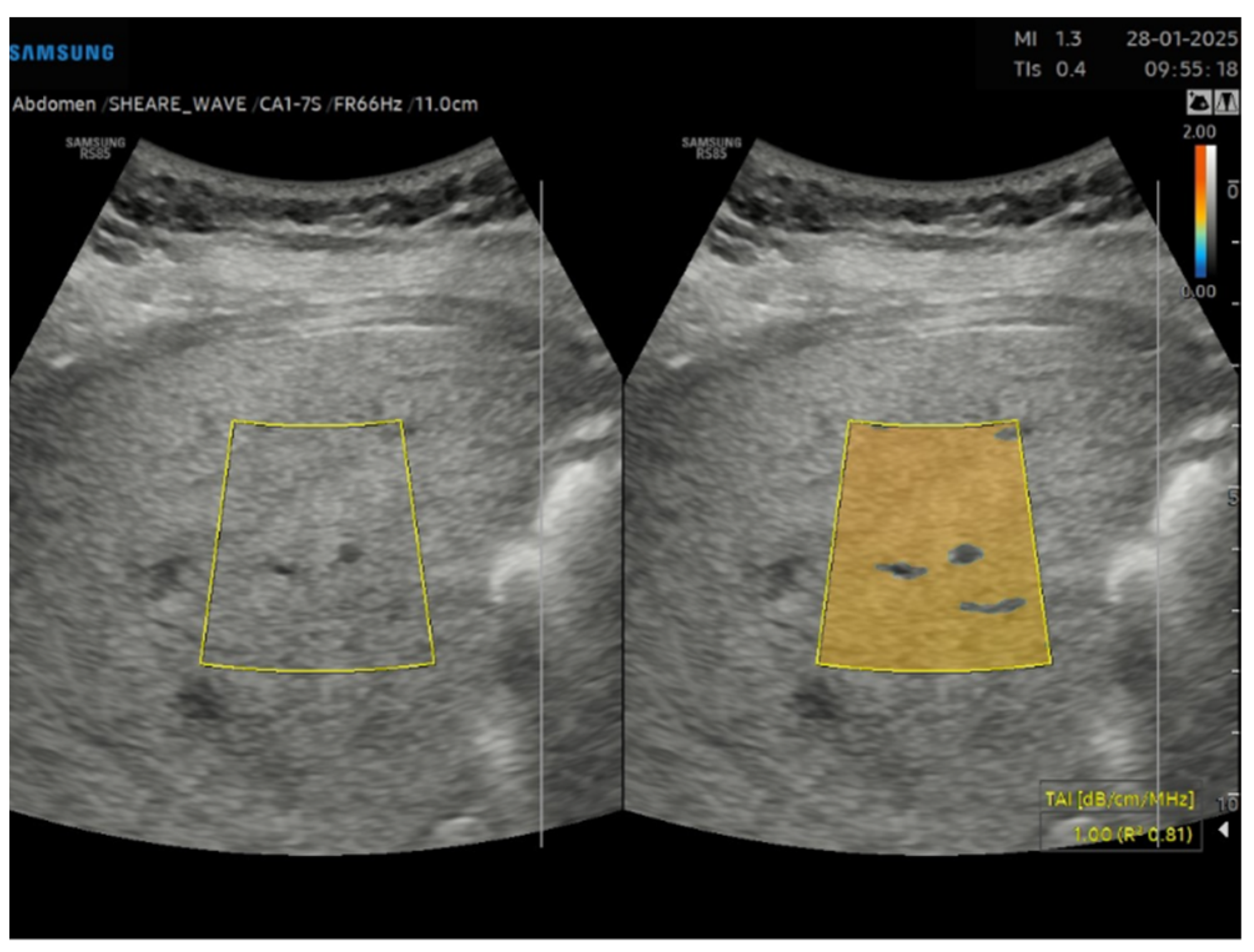

Figure 2) and TAI (

Figure 3) data were acquired and subsequently processed using proprietary algorithms developed and calibrated at the Samsung Medical Center [

27,

28]. These algorithms extracted relevant parameters, namely the attenuation coefficient and backscatter coefficient. A mathematical model grounded in established physical principles and incorporating empirical data, was then employed to translate these extracted parameters into an estimate of the liver USFF. Patients with clinical or morphological features of advanced liver diseases or cirrhosis, active viral hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, altered liver enzymes and heart failure were excluded. The collected data included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), TAI, TSI, USFF values, liver enzymes, comorbidities.

Participants were categorized into four groups based on steatosis grading assessed by US B-Mode examination: Group 1 (No steatosis), Group 2 (Mild steatosis), Group 3 (Moderate steatosis), and Group 4 (Severe steatosis). The primary outcome measure was the Ultrasonographic Fatty Liver Index (USFF). One-way ANOVA was conducted to assess for significant differences in mean USFF values between the four groups. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test to identify specific pairwise differences. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the mean USFF were calculated for each group. To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of the USFF in distinguishing between different levels of steatosis, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were generated for each group. The Youden Index was then utilized to identify the optimal cut-off points for the USFF within each group, maximizing the balance between sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing steatosis within that particular severity level. Due to the exploratory nature of ROC analysis no formal adjustment was applied.

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Commitee (Comitato Etico Territoriale Lazio Area 3) of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy on the 5 August 2020 (approval code 3278).

3. Results

This study evaluated a total of 95 patients. 11 patients were excluded because of liver enzymes alteration (n = 3), among which 1 patient received a diagnosis of active viral hepatitis, US morphologic features of cirrhosis (n = 3), heart failure (n = 1), technical issues in performing USFF measurements (n = 1), concomitant alcohol use disorder (n = 3). 84 patients were included (51 females, 33 males) with a mean age of 45.6 years (SD 12.5, range: 17–71 years). The population exhibited a higher prevalence of class II and III obesity (respectively 27 and 54 patients), with a mean BMI of 42.9 kg/m2 (SD 6.5, median 41.7 kg/m2).

A significant proportion of patients had prevalent comorbidities: 39.3% had type 2 diabetes, 35.7% had hypertension, and 16.7% had both. Dyslipidemia, defined as elevated LDL cholesterol levels (above 100 mg/dL for low-to-moderate cardiovascular risk and above 70 mg/dL for high or very high risk), was present in 76.2% of the cohort. Among these patients, 19.1% (n = 16) showed no evidence of steatosis (S0) on liver ultrasound; 7.1% (n = 6) patients had mild steatosis (S1), 46.4% (n = 39) had moderate steatosis (S2), 27.4% (n = 23) had severe steatosis (S3). The parameters related to BMI, 2DS Shearwave and USFF across the different steatosis grades are shown in

Table 1.

No statistically significant differences were found between the four groups regarding the degree of fibrosis measured by 2D shear wave elastography. Significant differences in mean USFF values were observed across the four steatosis grades groups (ANOVA,

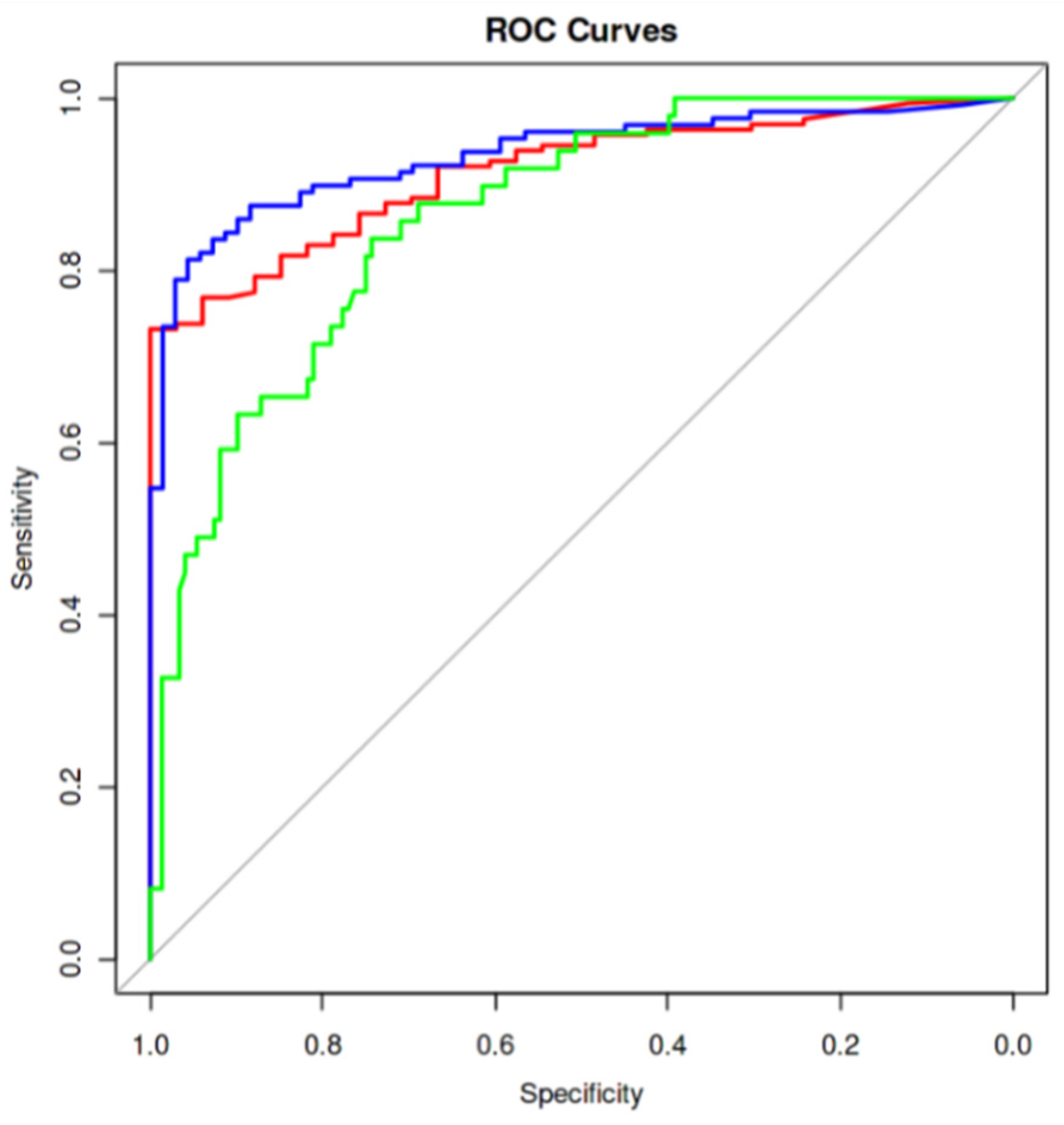

p < 0.001). Post-hoc analysis revealed significant pairwise differences between all groups. Mean USFF values increased progressively across the severity spectrum, with Group 1 (No steatosis) exhibiting the lowest mean (5.33 ± 2.00, 95% CI: 4.26–6.40), followed by Group 2 (Mild steatosis) (9.08 ± 2.19, 95% CI: 6.79–11.37), Group 3 (Moderate steatosis) (14.19 ± 4.89, 95% CI: 12.60–15.78), and Group 4 (Severe steatosis) exhibiting the highest mean (21.36 ± 5.28, 95% CI: 19.08–23.64). Based on the ROC curves (

Figure 4) and the Youden index, we propose the following cut-off values for classifying steatosis grades:

Grade 0 (No Steatosis): USFF < 7.33 (sensitivity 82% [95% CI: 57–93], specificity 93% [95% CI: 84–97]);

Grade 1 (Mild Steatosis): USFF < 11.66 (sensitivity 95% [95% CI: 78–99], specificity 88% [95% CI: 77–93]);

Grade 2 (Moderate Steatosis): USFF < 16.30 (sensitivity 82% [95% CI: 71–90], specificity 92% [95% CI: 74–98]).

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves evaluating the accuracy of the proposed cut-offs of Ultrasound Derived Fat Fraction (USFF) for classifying steatosis grades. Red curve represent the accuracy in differentiating absence of steatosis (S0) from mild (S1), moderate (S2), and severe steatosis (S3). Blue curve represents the accuracy in differentiating S0 and S1 from S2 and S3. Green curve represents the accuracy in differentiating S0, S1, and S2 from S3. The best performance is reached in differentiating S0 and S1 from S2 and S3 with an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.9335371.

Figure 4.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves evaluating the accuracy of the proposed cut-offs of Ultrasound Derived Fat Fraction (USFF) for classifying steatosis grades. Red curve represent the accuracy in differentiating absence of steatosis (S0) from mild (S1), moderate (S2), and severe steatosis (S3). Blue curve represents the accuracy in differentiating S0 and S1 from S2 and S3. Green curve represents the accuracy in differentiating S0, S1, and S2 from S3. The best performance is reached in differentiating S0 and S1 from S2 and S3 with an Area Under Curve (AUC) of 0.9335371.

4. Discussion

Early diagnosis of liver steatosis and its associated metabolic dysfunction is crucial, as disease evolution is potentially reversible through healthy lifestyle measures. Early diagnosis and timely therapy can prevent the progression to more severe liver conditions, such as cirrhosis and its complication. Transabdominal US should be used as the primary imaging method to identify hepatic steatosis because it is widely available and cost-effective [

29]. However, B-mode US has limited sensitivity and does not reliably detect steatosis when it is less than 20% [

30,

31]. Moreover, the grading of steatosis can be inaccurate due to the operator’s subjective visual assessment. Stratifying the population according to steatosis grading is important to personalize treatment. In the literature, there are few studies that have analyzed the accuracy of USFF for detecting liver steatosis, and no established threshold for grading has been defined. Some authors have proposed USFF as a simple and accurate imaging biomarker for assessing hepatic steatosis [

23,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

In particular, De Robertis et al. analyzed 122 patient, comparing conventional US and USFF with MRI-PDFF for the detection of hepatic steatosis and quantification of liver fat content. They demonstrated that USFF and MRI-PDFF had high agreement and positive correlation, concluding that USFF reliably quantifies liver fat content and improves the diagnostic value of US for detecting hepatic steatosis [

23].

Jung et al. compared the diagnostic accuracy of the quantitative USFF estimator with the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) in the diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) using contemporaneous MRI-derived PDFF as the reference standard. They demonstrated that the quantitative USFF estimator was more accurate than the controlled attenuation parameter in diagnosing hepatic steatosis in patients with or suspected of having non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [

29]. Rónaszéki et al. investigated the diagnostic performance of the quantitative ultrasound (QUS) biomarkers such as TAI and TSI, performed with a Samsung RS85 Prestige ultrasound system. They demonstrated that both TAI and TSI showed significant correlation with grade of steatosis detected by MRI-PDFF, proposing ideal cut-off for both TAI and TSI for each group [

35]. Following previous findings, our study demonstrates a strong correlation between the USFF and visual assessment of steatosis in a population of obese adult Caucasian individuals. The identified cut-off values for USFF provide a statistically significant basis for differentiating between varying degrees of liver fat accumulation. This suggests that USFF may offer a valuable alternative to subjective visual estimations, providing a more objective and reproducible assessment of hepatic steatosis. Nonetheless, the proposed cut-offs were identified in a specific population, namely obese patients, and may not be directly applicable to populations with different BMI distributions. Moreover, variations in results could arise when using different ultrasound devices or software versions. However, Sporea et al. [

36] reported comparable cut-offs when assessing USFF in a cohort including non-obese, overweight, and obese individuals using a Siemens ACUSON Sequoia system.

While promising, USFF should be considered within the context of other non-invasive techniques for quantifying liver fat. CAP, assessed via transient elastography, is another established method for evaluating steatosis [

37]. However, CAP may require specialized equipment, and its accuracy can be diminished in severely obese patients with a BMI exceeding 30 kg/m

2 [

38]. In contrast, USFF possesses the significant advantage of being readily incorporated into standard abdominal ultrasound examinations, enhancing its practicality for routine clinical use.

Although promising, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The principal limitation of this study is that USFF measurements were validated only against conventional visual ultrasound assessment rather than against gold-standard modalities such as MRI-PDFF or liver biopsy. While this approach allows for internal comparison within a real-world clinical setting, it inevitably limits the diagnostic accuracy that can be inferred and reduces the external strength of the proposed cut-off values. The lack of gold-standard validation also restricts the comparability of our findings with other quantitative ultrasound studies that reference MRI-PDFF or histology. For these reasons, the cut-off values identified in the present cohort should be considered preliminary and applicable primarily within similar clinical and technical contexts. Future studies incorporating MRI-based or histologic validation are essential to confirm the diagnostic performance of USFF and to harmonize thresholds across different ultrasound systems. Second, the relatively small sample size—particularly in the groups with no or mild steatosis—limits the generalizability of our findings, and larger cohorts may yield different and potentially more robust cut-off values. However, the predominance of higher steatosis grades reflects the high prevalence of class II–III obesity in the study cohort, which aligns with the primary objective of this investigation. Nonetheless, the identified cut-offs are consistent with those previously reported in the literature. Third, USFF measurements were performed by a single highly experienced operator. Although this approach ensured internal consistency, the assessment of inter-observer variability could have strengthened the reliability of the results. Lastly, the population consisted exclusively of obese candidates for bariatric surgery, and results may not fully apply to non-obese or general populations.

The potential clinical implications of these findings are significant. If validated further, USFF could facilitate earlier diagnosis and more personalized treatment strategies for individuals with MASLD. By providing a standardized and quantitative measure of liver fat, USFF may help clinicians better monitor disease progression, assess treatment response, and identify patients at higher risk for complications. Indeed, our proposed cut-off values should be regarded as preliminary and serve as proof of concept rather than definitive thresholds. Large-scale studies comparing USFF with gold-standard techniques like liver biopsy and MRI-PDFF are crucial to establish the accuracy and reliability of USFF measurements. Also, it is crucial to standardize USFF measurement protocols across different ultrasound systems and sonographers to ensure consistent and reliable results. Nonetheless, future studies should extend this approach to include patients with different BMI, ethnicities, metabolic profiles and patterns of alcohol consumption, thereby capturing the full continuum of MASLD and refining its diagnostic framework.

5. Conclusions

USFF showed strong correlation with visual grading of hepatic steatosis and provided preliminary diagnostic cut-off values in obese patients. By integrating quantitative analysis into routine abdominal ultrasound, USFF may improve diagnostic accuracy and allow objective monitoring of steatosis over time. However, larger studies comparing USFF with established reference standards and evaluating broader patient populations are required before widespread clinical adoption. In particular, although USFF is promising, it should be considered complementary and not a replacement for MRI-PDFF in clinical trials until further robust validation is available.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.I. and F.P.; methodology, C.A., N.D.M. and F.P.; validation, F.I., C.A. and F.P.; investigation, F.I., C.A., T.R., L.P., G.C., C.C. and S.V.; data curation, F.I., C.A., T.R., L.P., G.C., C.C. and S.V.; writing—original draft preparation, F.I. and T.R.; writing—review and editing, C.A. and F.P.; supervision, N.D.M. and F.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Ethical Commitee (Comitato Etico Territoriale Lazio Area 3) of the Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, Italy on the 5 August 2020 (approval code 3278).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Fondazione Roma for the invaluable support to our scientific research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology 2023, 78, 1966–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, A.J.; George, J. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999–2014.e1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, P.N.; Sarin, S.K.; Anstee, Q.M.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wong, V.W.-S.; Dufour, J.-F.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De, A.; Bhagat, N.; Mehta, M.; Taneja, S.; Duseja, A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) definition is better than MAFLD criteria for lean patients with NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 2024, 80, e61–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, T.H.; Wu, C.H.; Lee, Y.W.; Chang, C.C. Prevalence, trends, and characteristics of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease among the US population aged 12–79 years. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 36, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, M.H.; Yeo, Y.H.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Zou, B.; Wu, Y.; Ye, Q.; Huang, D.Q.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. 2019 Global NAFLD Prevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off Clin. Pr. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2022, 20, 2809–2817.e28. [Google Scholar]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatol. Baltim. Md. 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Costante, F.; Airola, C.; Santopaolo, F.; Gasbarrini, A.; Pompili, M.; Ponziani, F.R. Immunotherapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: Lights and shadows. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 14, 1622–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. JAMA 2015, 313, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.M.J.; Lai, M. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Ann Intern Med. 2025, 178, ITC1-16. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, R.G. Ultrasound of Diffuse Liver Disease Including Elastography. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 57, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scatarige, J.C.; Scott, W.W.; Donovan, P.J.; Siegelman, S.S.; Sanders, R.C. Fatty infiltration of the liver: Ultrasonographic and computed tomographic correlation. J. Ultrasound Med. Off. J. Am. Inst. Ultrasound Med. 1984, 3, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Z.X.; Mehta, B.; Kusel, K.; Seow, J.; Zelesco, M.; Abbott, S.; Simons, R.; Boardman, G.; Welman, C.J.; Ayonrinde, O.T. Hepatic steatosis: Qualitative and quantitative sonographic assessment in comparison to histology. Australas. J. Ultrasound Med. 2024, 27, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura Almeida, A.; Cotrim, H.P.; Barbosa, D.B.V.; de Athayde, L.G.M.; Santos, A.S.; Bitencourt, A.G.V.; de Freitas, L.A.R.; Rios, A.; Alves, E. Fatty liver disease in severe obese patients: Diagnostic value of abdominal ultrasound. World J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 1415–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottin, C.C.; Moretto, M.; Padoin, A.V.; Swarowsky, A.M.; Toneto, M.G.; Glock, L.; Repetto, G. The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis in morbidly obese patients. Obes. Surg. 2004, 14, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, S.B.; Cruite, I.; Hamilton, G.; Sirlin, C.B. Quantitative Assessment of Liver Fat with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging JMRI 2011, 34, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, A.; Desai, A.; Hamilton, G.; Wolfson, T.; Gamst, A.; Lam, J.; Clark, L.; Hooker, J.; Chavez, T.; Ang, B.D.; et al. Accuracy of MR imaging-estimated proton density fat fraction for classification of dichotomized histologic steatosis grades in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Radiology 2015, 274, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paige, J.S.; Bernstein, G.S.; Heba, E.; Costa, E.A.C.; Fereirra, M.; Wolfson, T.; Gamst, A.C.; Valasek, M.A.; Lin, G.Y.; Han, A.; et al. A Pilot Comparative Study of Quantitative Ultrasound, Conventional Ultrasound, and MRI for Predicting Histology-Determined Steatosis Grade in Adult Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2017, 208, W168–W177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.C.; Heba, E.; Wolfson, T.; Ang, B.; Gamst, A.; Han, A.; Erdman, J.W.; O’bRien, W.D.; Andre, M.P.; Sirlin, C.B.; et al. Noninvasive Diagnosis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Quantification of Liver Fat Using a New Quantitative Ultrasound Technique. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2015, 13, 1337–1345.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.H.; Eissa, M.; Bluth, E.I.; Gulotta, P.M.; Davis, N.K. Hepatorenal index as an accurate, simple, and effective tool in screening for steatosis. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2012, 199, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oelze, M.L.; Mamou, J. Review of Quantitative Ultrasound: Envelope Statistics and Backscatter Coefficient Imaging and Contributions to Diagnostic Ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control. 2016, 63, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraioli, G.; Berzigotti, A.; Barr, R.G.; Choi, B.I.; Cui, X.W.; Dong, Y.; Gilja, O.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Moriyasu, F.; et al. Quantification of Liver Fat Content with Ultrasound: A WFUMB Position Paper. Ultrasound. Med. Biol. 2021, 47, 2803–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Robertis, R.; Spoto, F.; Autelitano, D.; Guagenti, D.; Olivieri, A.; Zanutto, P.; Incarbone, G.; D’oNofrio, M. Ultrasound-derived fat fraction for detection of hepatic steatosis and quantification of liver fat content. Radiol. Med. 2023, 128, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, J.R.; Thapaliya, S.; Tkach, J.A.; Trout, A.T. Quantification of Hepatic Steatosis by Ultrasound: Prospective Comparison with MRI Proton Density Fat Fraction as Reference Standard. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2022, 219, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak, K.; Paluch, M.; Cudzik, M.; Syska, K.; Gawlikowska, W.; Janczura, J. From steatosis to cirrhosis: The role of obesity in the progression of liver disease. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2025, 24, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Uppot, R.N. Technical challenges of imaging & image-guided interventions in obese patients. Br. J. Radiol. 2018, 91, 20170931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, J.H.; Cho, S.J.; Choi, S.C.; Jee, J.H.; Yun, J.; Hwang, J.A.; Park, G.; Kim, K.; Kang, W.; Kang, M.; et al. Diagnostic performance of quantitative ultrasonography for hepatic steatosis in a health screening program: A prospective single-center study. Ultrasonography 2024, 43, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadeh, S.; Younossi, Z.M.; Remer, E.M.; Gramlich, T.; Ong, J.P.; Hurley, M.; Mullen, K.D.; Cooper, J.N.; Sheridan, M.J. The utility of radiological imaging in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2002, 123, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Castro, F.; Cheruku, S.; Jain, S.; Webb, B.; Gleason, T.; Stevens, W.R. Hepatic MRI for fat quantitation: Its relationship to fat morphology, diagnosis, and ultrasound. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2005, 39, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Han, A.; Madamba, E.; Bettencourt, R.; Loomba, R.R.; Boehringer, A.S.; Andre, M.P.; Erdman, J.W., Jr.; O’Brien, W.D., Jr.; Fowler, K.J.; et al. Direct Comparison of Quantitative US versus Controlled Attenuation Parameter for Liver Fat Assessment Using MRI Proton Density Fat Fraction as the Reference Standard in Patients Suspected of Having NAFLD. Radiology 2022, 304, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kubale, R.; Schneider, G.; Lessenich, C.P.N.; Buecker, A.; Wassenberg, S.; Torres, G.; Gurung, A.; Hall, T.; Labyed, Y. Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction for Hepatic Steatosis Assessment: Prospective Study of Agreement with MRI PDFF and Sources of Variability in a Heterogeneous Population. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2024, 222, e2330775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labyed, Y.; Milkowski, A. Novel Method for Ultrasound-Derived Fat Fraction Using an Integrated Phantom. J. Ultrasound Med. Off. J. Am. Inst. Ultrasound Med. 2020, 39, 2427–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, X.L.; Wang, S.W.; Wei, L.; Dong, Y. Hepatic steatosis using ultrasound-derived fat fraction: First technical and clinical evaluation. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2024, 86, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rónaszéki, A.D.; Budai, B.K.; Csongrády, B.; Stollmayer, R.; Hagymási, K.; Werling, K.; Fodor, T.; Folhoffer, A.; Kalina, I.; Győri, G.; et al. Tissue attenuation imaging and tissue scatter imaging for quantitative ultrasound evaluation of hepatic steatosis. Medicine 2022, 101, e29708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sporea, I.; Lupusoru, R.; Sirli, R.; Bende, F.; Cotrau, R.; Foncea, C.; Popescu, A. Fatty liver quantification using ultrasound derived fat fraction (usff) as compared to controlled attenuation parameter (cap) in a mixed cohort of patients. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 48, S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavaglione, F.; De Vincentis, A.; Bruni, V.; Gallo, I.F.; Carotti, S.; Tuccinardi, D.; Spagnolo, G.; Ciociola, E.; Mancina, R.M.; Jamialahmadi, O.; et al. Accuracy of controlled attenuation parameter for assessing liver steatosis in individuals with morbid obesity before bariatric surgery. Liver Int. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Liver 2022, 42, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.T.; Xiang, L.L.; Qi, F.; Zhang, Y.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, X.Q. Accuracy of controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) and liver stiffness measurement (LSM) for assessing steatosis and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 51, 101547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).