Frozen Section Studies of Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Systems: A Review Article

Abstract

1. Introduction

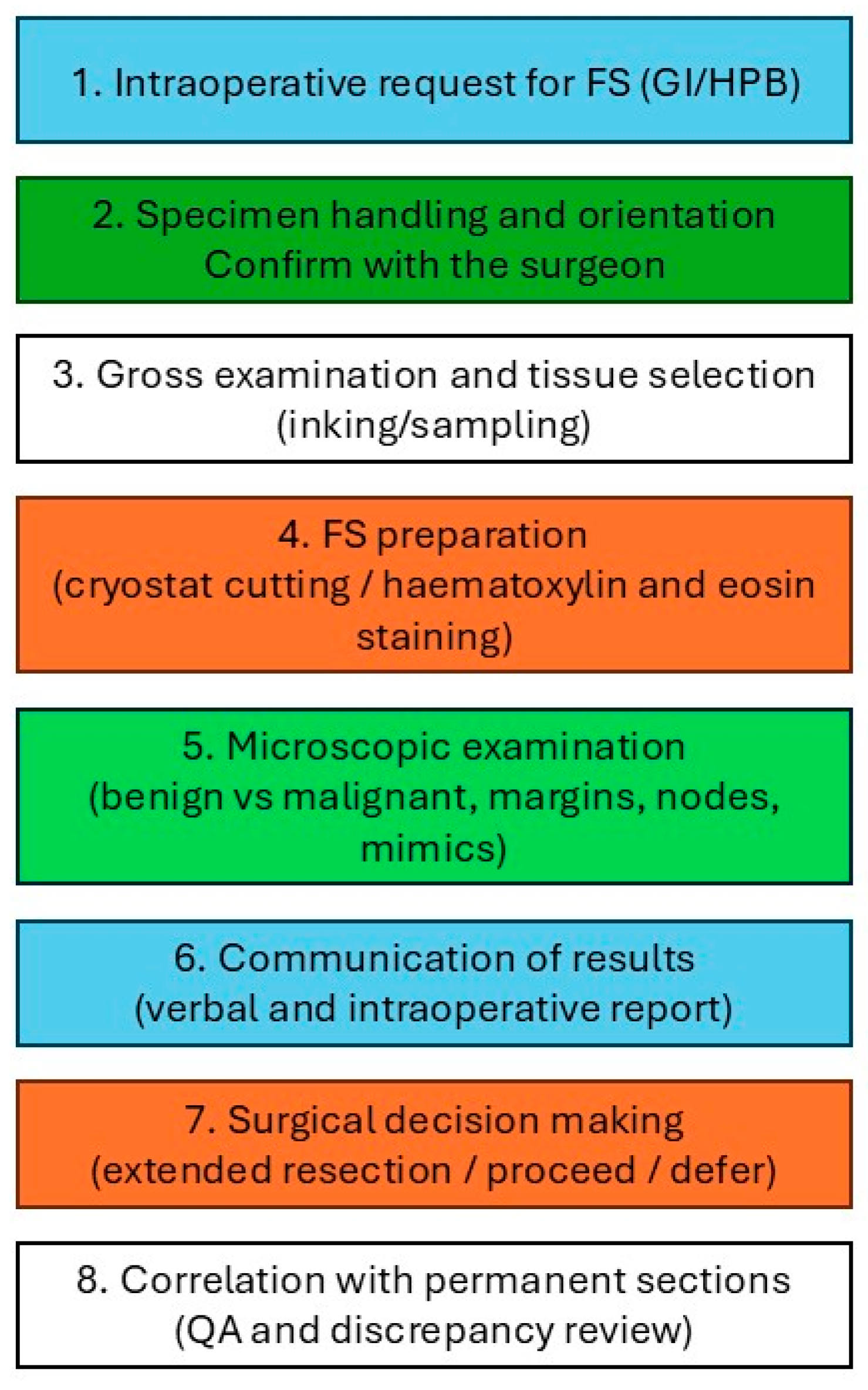

2. Standard Histopathological Procedure

- Fresh tissue is submitted immediately by the surgeon to the histopathology department.

- The tissue is rapidly frozen in a cryostat by a pathologist or technologist.

- Thin sections, typically 5–10 micrometres thick, are cut, mounted on slides, and stained using a rapid haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) method.

- The pathologist promptly evaluates the prepared slides.

- In selected cases, particularly for lymph node assessment, cytology imprints may be prepared to aid diagnosis.

- The pathologist communicates the preliminary findings directly to the surgeon in the operating theatre, typically via oral report.

- Following FS analysis, the tissue is fixed in formalin for standard processing and preparation of permanent sections, which are incorporated into the final pathology report.

- FS slides are archived together with permanent sections for each case, supporting quality control and correlation.

3. Turnaround Time

4. Types of Specimens in GI and Hepatobiliary Frozen Section

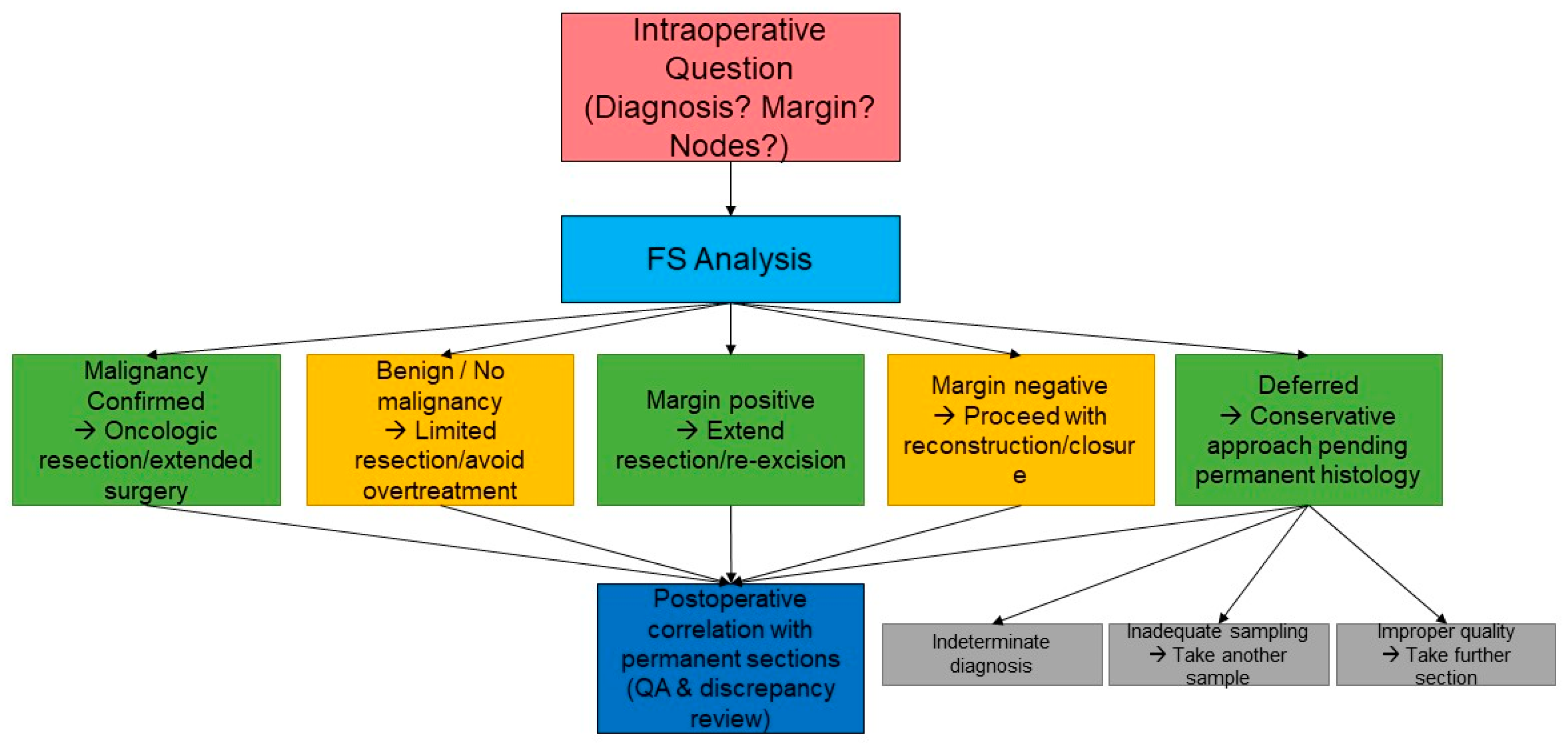

4.1. Margin Assessment

4.2. Lymph Node Examination

4.3. Tumour Typing/Diagnosis Confirmation

4.4. Evaluation of Biliary Lesions

4.5. Assessment of Viability/Infarction

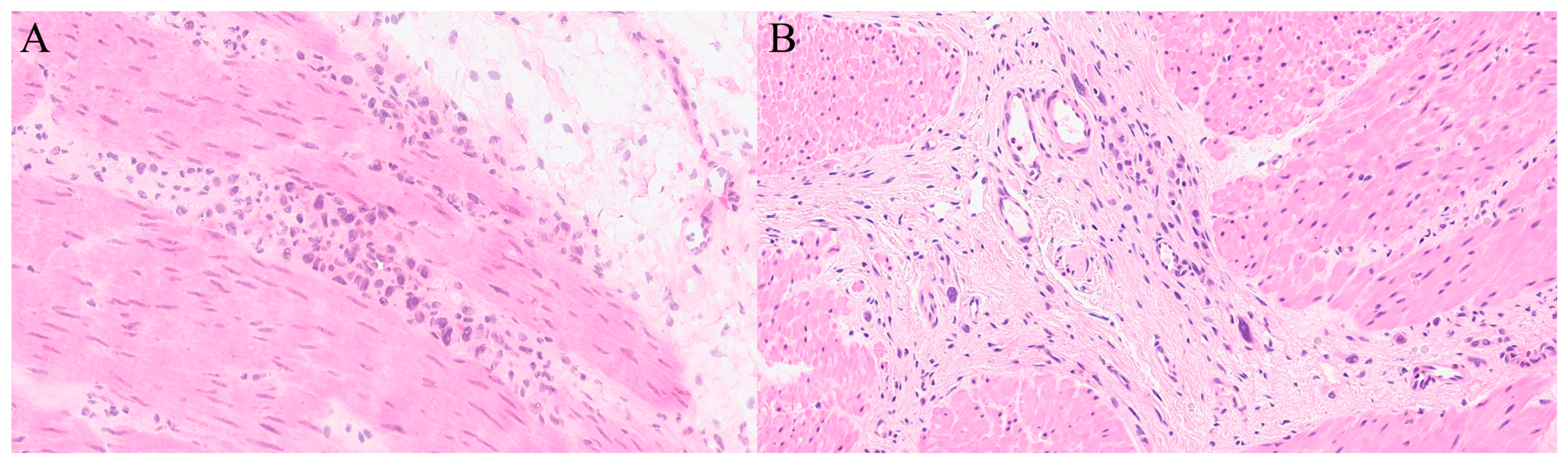

4.6. Unexpected Lesions

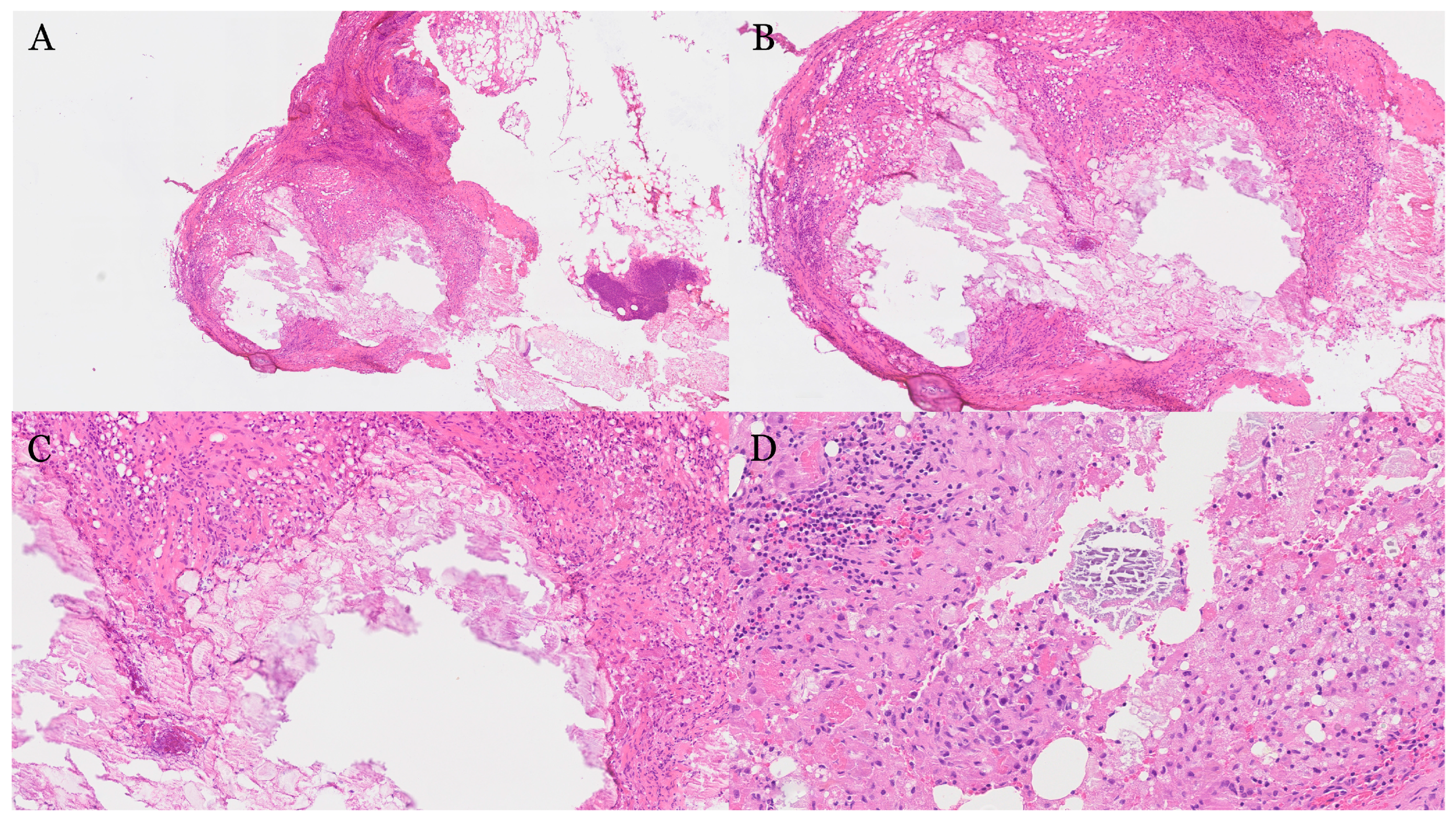

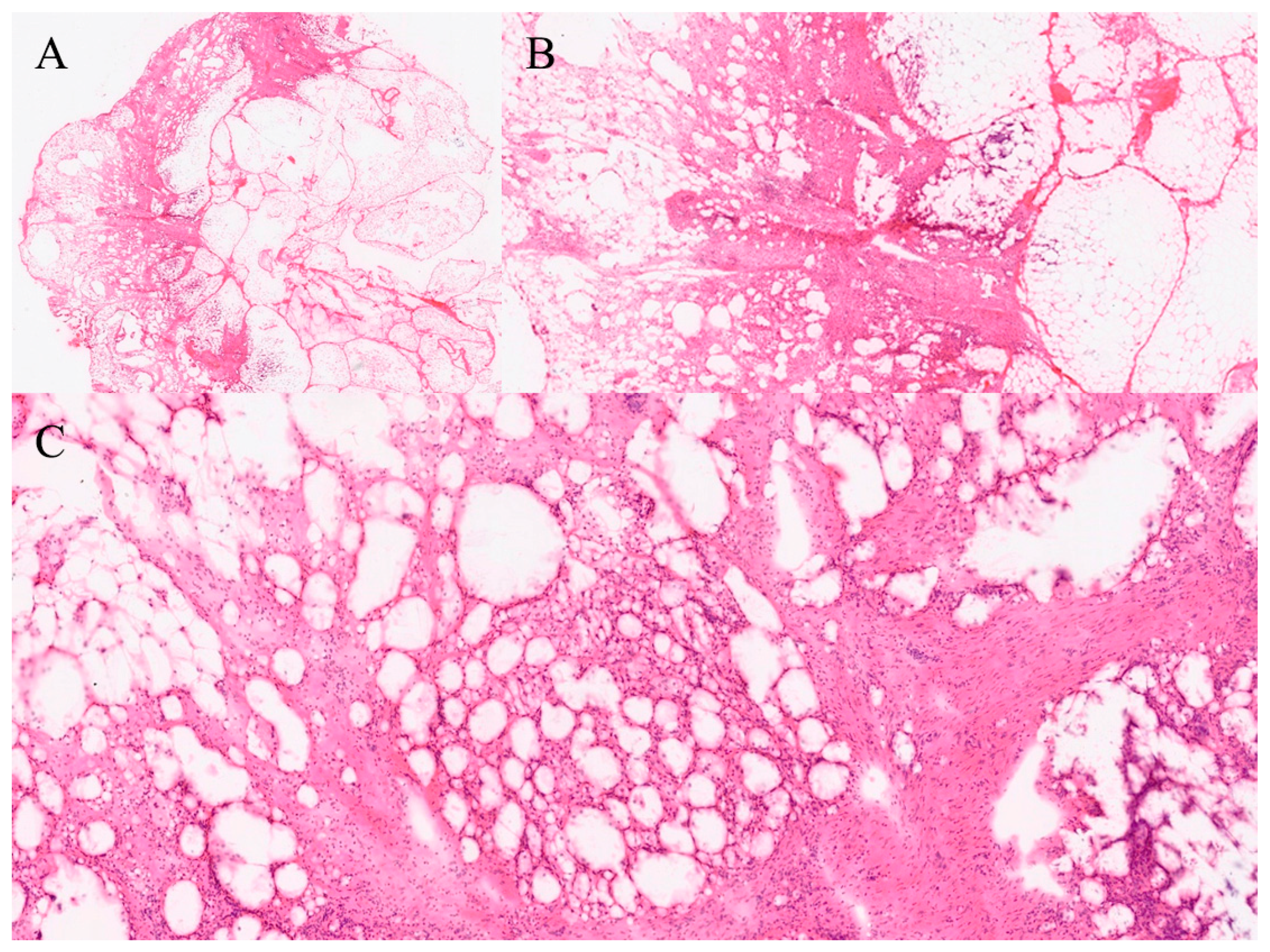

4.7. Cystic Lesions of the Liver or Pancreas

4.8. Tissue Identification and Adequacy

5. Errors

5.1. Pre-Analytical Errors

5.2. Analytical Errors

5.3. Post-Analytical Errors

6. Deferred Diagnosis

7. Accuracy, Concordance and Discrepancy

8. Oesophagus/Stomach

9. Small Bowel, Colon and Anal Canal

10. Liver

11. Pancreas

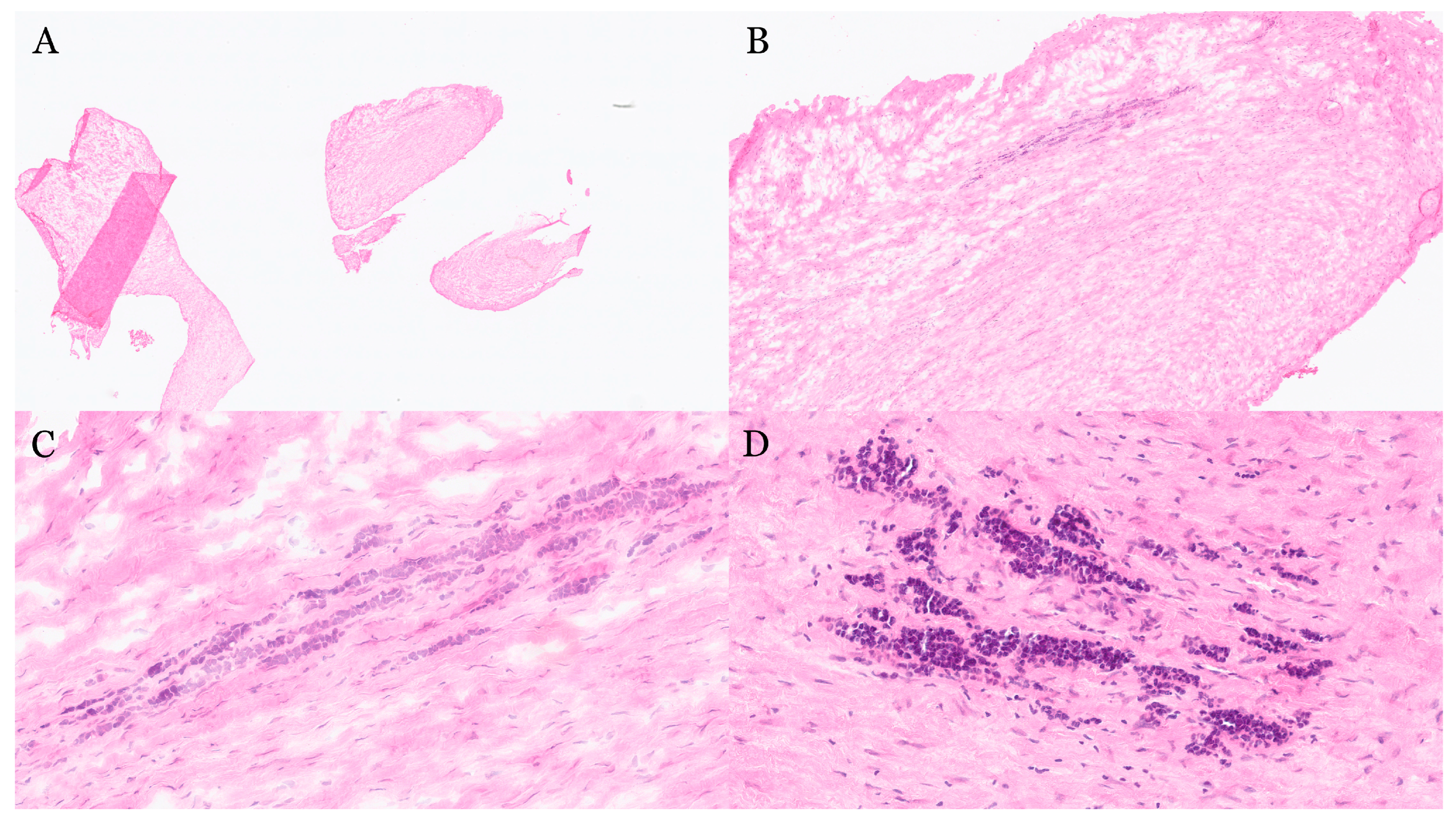

12. Bile Duct

13. Gallbladder

14. Lymph Nodes

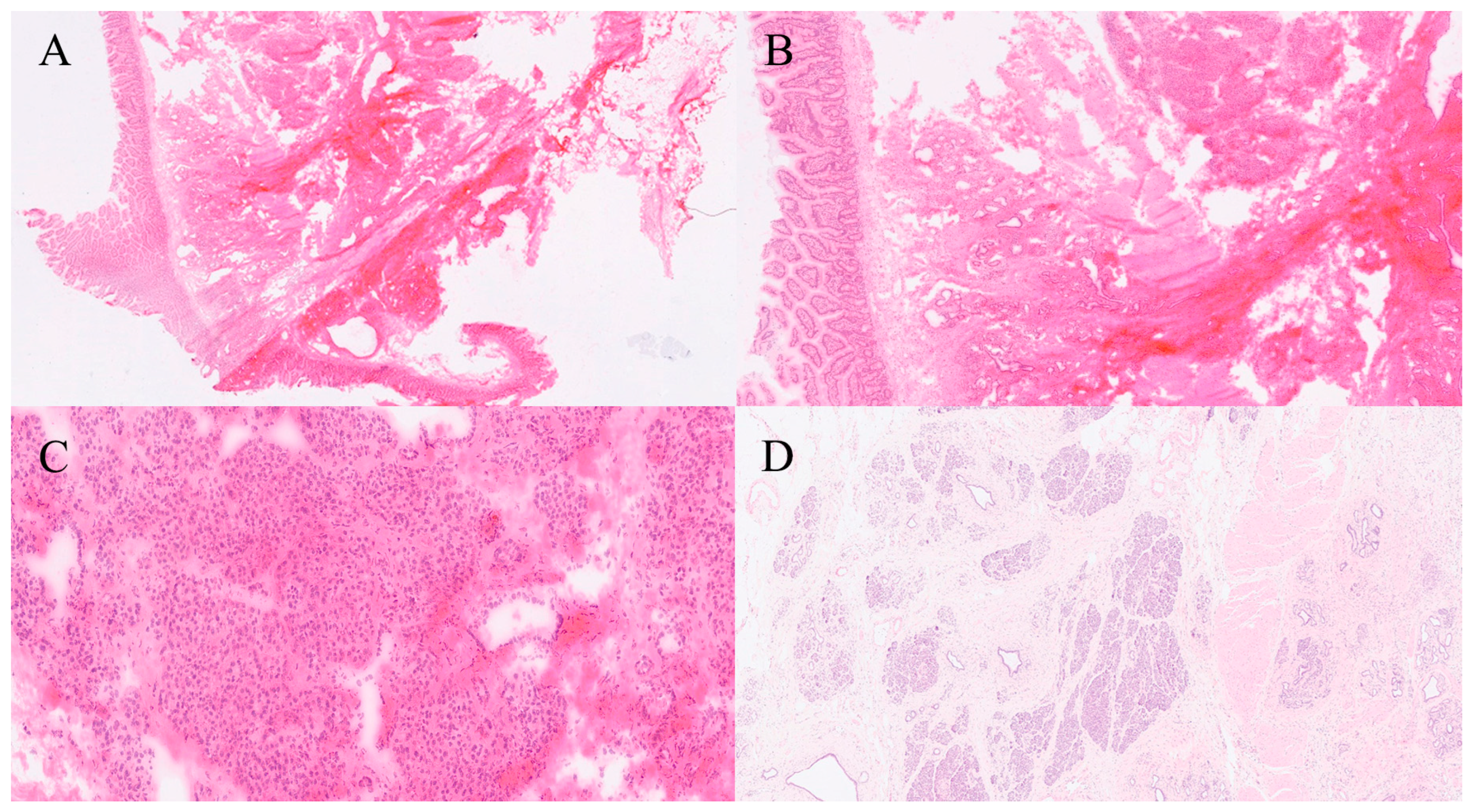

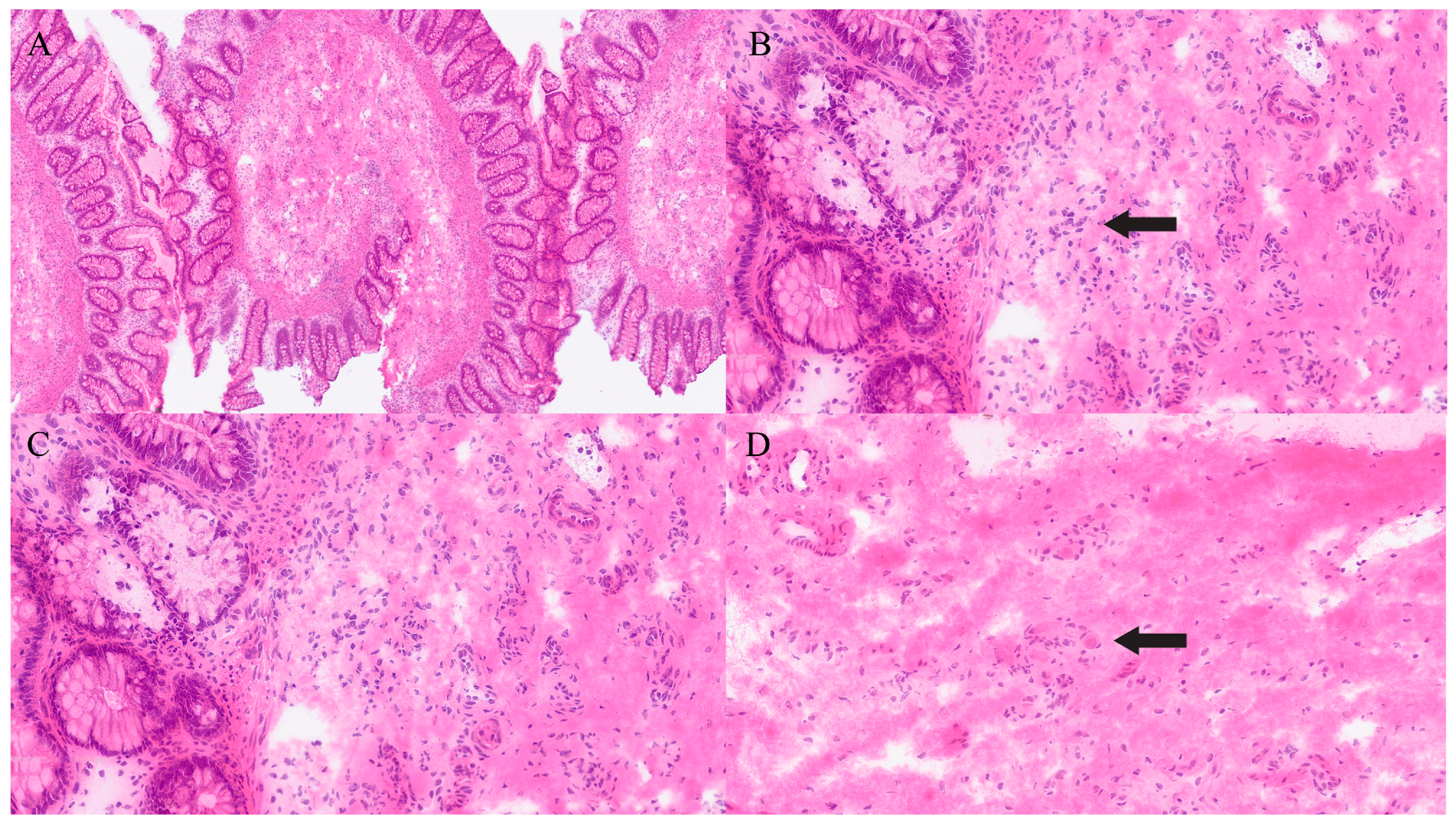

15. Peritoneum/Omentum

16. Others (From Deceased Donors for Transplant)

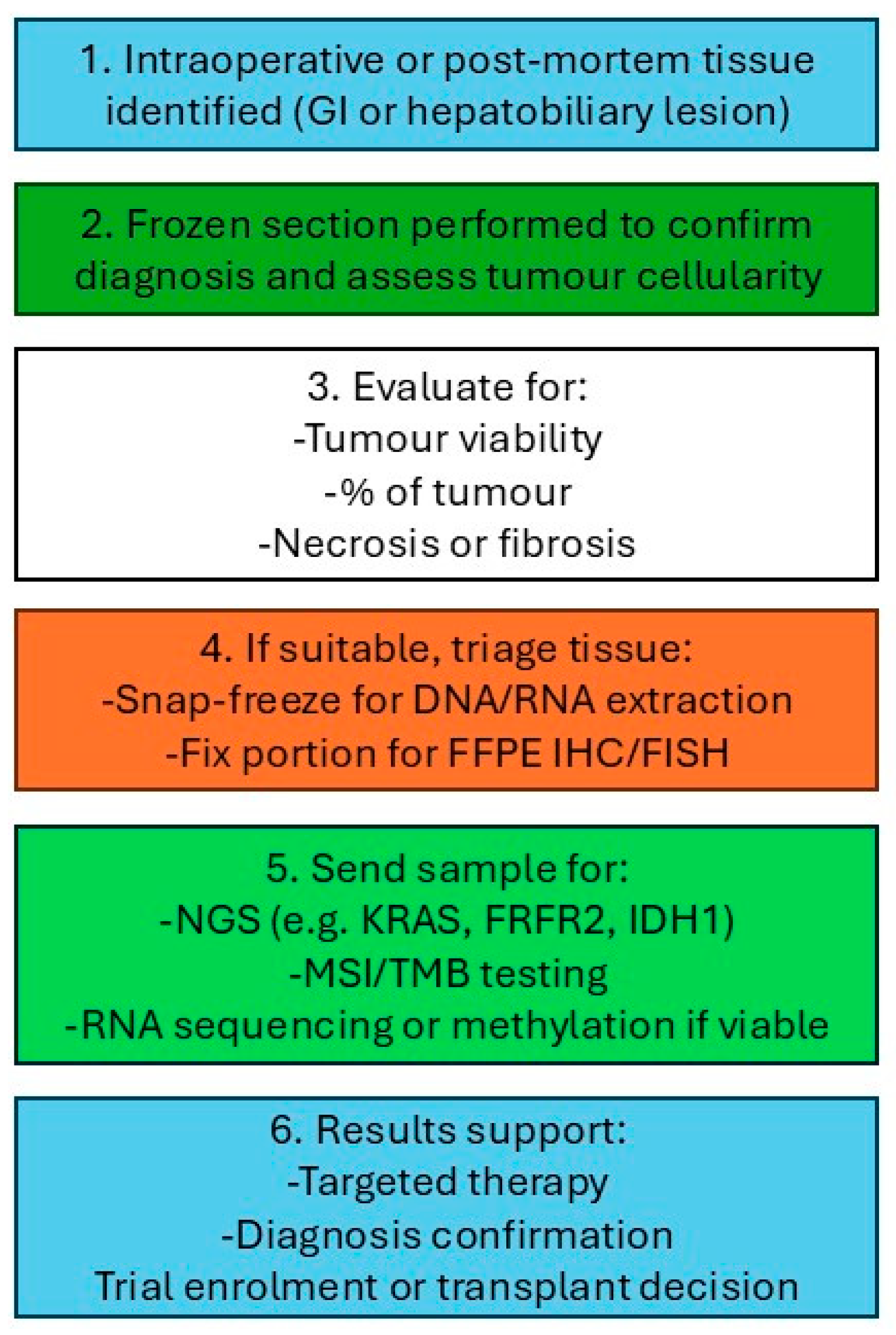

17. Frozen Section for Molecular Pathology

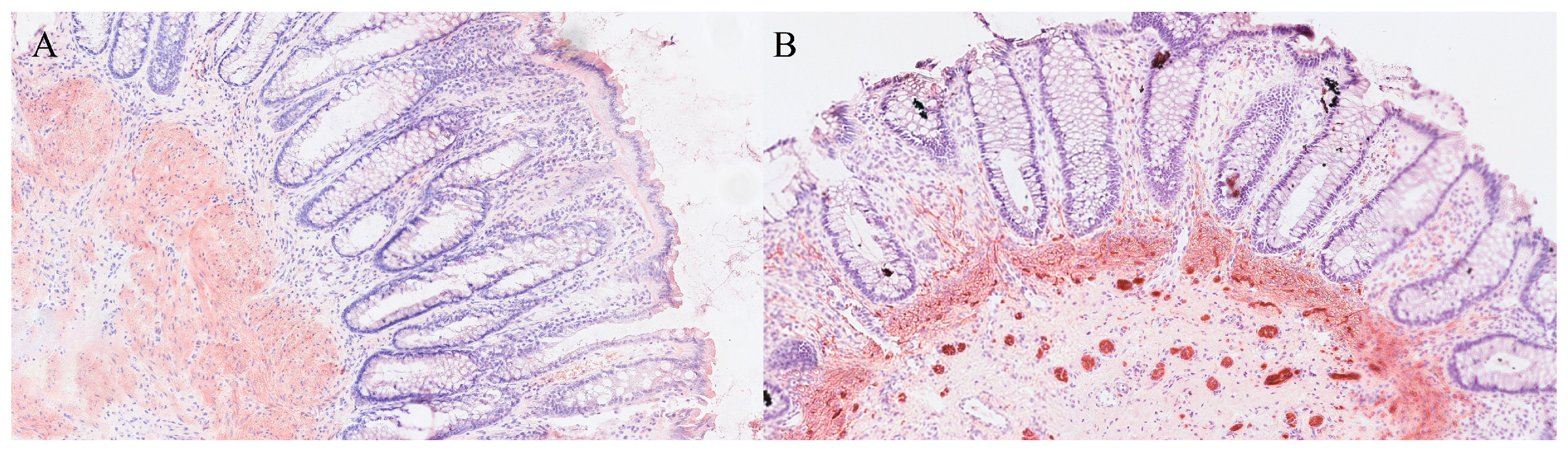

18. Hirschsprung Disease

19. Pitfalls and Limitations

20. Impact of Chemotherapy and Immunotherapy on Interpretation of FS

21. Future Direction

22. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FS | Frozen section |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| PS | Paraffin section |

| CAP | College of American Pathologists |

| TAT | Turnaround time |

| NUH | Nottingham University Hospitals |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| NLP | Natural language processing |

| BilIN | Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia |

| ICPN | Intracholecystic papillary neoplasm |

| PanIN | Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia |

| H&E | Haematoxylin and eosin |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal stromal tumour |

| FRCPath | Fellowship of the Royal College of Pathologists |

| HIPEC | Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy |

| ICIs | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

References

- Rosai, J. Rosai and Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology, 11th ed.; Elsevier: Edinburgh, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pearse, A.G.; Slee, K. Histochemistry: Theoretical and Applied, Vol. 1, 3rd ed.; J. & A. Churchill Ltd.: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Mahe, E.; Bissonnette, C.; Auger, M. Intraoperative pathology consultation: Error, cause and impact. Can. J. Surg. 2013, 56, E13–E18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, D.J.; Kelly, S.M.; Wiehagen, L.; Yousem, S.A. Tissue adequacy for ancillary studies beyond frozen section: A potential method for improving diagnostic and therapeutic results. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 21, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, J.R.; Hunt, H.V. Practical issues for frozen section diagnosis in gastrointestinal and liver diseases. J. Gastrointestin. Liver Dis. 2010, 19, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nagtegaal, I.D.; Odze, R.D.; Klimstra, D.; Paradis, V.; Rugge, M.; Schirmacher, P.; Washington, K.M.; Carneiro, F.; Cree, I.A.; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology 2020, 76, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Abbas, A.K.; Aster, J.C. Robbins Basic Pathology, 10th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vazzano, J.; Chen, W.; Frankel, W.L. Intraoperative frozen section evaluation of pancreatic specimens and related liver lesions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2025, 149, e63–e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, A.D.; Portmann, B.C.; Ferrell, L.D. MacSween’s Pathology of the Liver, 7th ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dillhoff, M.; Yates, R.; Wall, K.; Muscarella, P.; Melvin, W.S.; Ellison, E.C.; Bloomston, M. Intraoperative assessment of pancreatic neck margin at the time of pancreaticoduodenectomy increases likelihood of margin-negative resection in patients with pancreatic cancer. J. Gastrointest Surg. 2009, 13, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, K.; Smith, C.; Langer, J.C. Reliability of intraoperative frozen sections in the management of Hirschsprung’s disease. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2004, 39, 1345–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, H.; Mohsenifar, Z.; Alavi, S.N. The diagnostic accuracy of frozen section compared to permanent section: A single center study in Iran. Iran. J. Pathol. 2015, 10, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meunier, R.; Kim, K.; Darwish, N.; Gilani, S.M. Frozen section analysis in community settings: Diagnostic challenges and key considerations. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2025, 42, 150903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mclean, T.; Fitzgerald, C.; Eagan, A.; Long, S.M.; Cracchiolo, J.; Shah, J.; Patel, S.; Ganly, I.; Dogan, S.; Cohen, M.A.; et al. Understanding frozen section histopathology in sinonasal and anterior skull base malignancy and proposed reporting guidelines. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 128, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, S.E. Sternberg’s Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 6th ed.; Wolters Kluwer: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, C.W.; Johnston, W.W.; Berry, A.; Nguyen, G.K.; Michael, A.C. Rapid On-Site Evaluation (ROSE) for Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy: Impact, Accuracy, and Limitations. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2020, 48, 1092–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.L.; Witt, B.L.; Lopez-Calderon, L.E.; Layfield, L.J. The Influence of Rapid Onsite Evaluation on the Adequacy Rate of Fine-Needle Aspiration Cytology: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 139, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cunha Santos, G. The Petals and Thorns of ROSE (Rapid On-Site Evaluation). Cancer Cytopathol. 2013, 121, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, Z.R.; Wong, A.; Rosenthal, J.; Wang, Y.; Spencer, D.; Ji, H.P. Ultra-Rapid Droplet Digital PCR Enables Intraoperative Molecular Diagnostics with <20-Minute Turnaround. Med 2024, 5, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Qiu, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Rapid Intraoperative Multi-Molecular Diagnosis of Glioma. EBioMedicine 2023, 95, 104798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, H. Intra-operative frozen section consultation: Concepts, applications and limitations. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2006, 13, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gephardt, G.N.; Zarbo, R.J. Interinstitutional comparison of frozen-section consultations: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 90,538 cases in 461 institutions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1996, 120, 804–809. [Google Scholar]

- College of American Pathologists (CAP). Laboratory Accreditation Program: Anatomic Pathology Checklist; CAP: Northfield, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Jorns, J.M.; Visscher, D.; Sabel, M.; Breslin, T.; Healy, P.; Daignaut, S.; Myers, J.L.; Wu, A.J. Intraoperative frozen section analysis of margins in breast conserving surgery significantly decreases reoperative rates: One-year experience at an ambulatory surgical center. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2012, 138, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhleh, R.E.; Fitzgibbons, P.L. Quality Management in Anatomic Pathology: Promoting Patient Safety Through Systems Improvement and Error Reduction; CAP Press: Northfield, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Novis, D.A.; Zarbo, R.J. Interinstitutional comparison of frozen section turnaround time: A College of American Pathologists Q-Probes study of 32,868 frozen sections in 700 hospitals. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 1997, 121, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rima, S.; Santhosh, A.; Roy, S. A retrospective study on turnaround time for frozen sections—A tertiary care centre experience from southern India. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2022, 16, EC42–EC45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddoughi, S.A.; Mitchell, K.G.; Antonoff, M.B.; Fruth, K.M.; Taswell, J.; Mounajjed, T.; Hofstetter, W.W.L.; Rice, D.C.; Shen, K.R.; Blackmon, S.H.; et al. Analysis of esophagectomy margin practice and survival implications. Ann. Thorac Surg. 2022, 113, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.K.; Babu, A.S. Understanding the lymphatics: Review of the N category in the updated TNM staging of cancers of the digestive system. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, 215, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumgart, L.H.; Schwartz, L.H.; DeMatteo, R.P.; Hann, L.E. Surgical and radiologic anatomy of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. In Blumgart’s Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, 6th ed.; Jarnagin, W.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 32–59.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.; Hu, C.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ji, G.; Ge, S.; Wang, X.; Ming, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Lymph node metastasis in cancer progression: Molecular mechanisms, clinical significance and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, B.S.; Deka, M.; Salvi, M.; Das, B.K.; Goswami, B.C. Frozen section versus permanent section in cancer diagnosis: A single centre study. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Care 2022, 7, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechago, J. Frozen section examination of liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2005, 129, 1610–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.S.; Deodhar, K.K.; Ramadwar, M.; Bal, M.; Kumar, R.; Goel, M.; Saklani, A.; Shrikhande, S.V. An audit of frozen sections for suspected gastrointestinal malignancies in a tertiary referral hospital in India. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2022, 65, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, A.; Ashwini, N.S.; Rath, I.; Bihari, C.; Sasturkar, S.V.; Pamecha, V. Utility and diagnostic accuracy of intraoperative frozen sections in hepato-pancreato-biliary surgical pathology. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Chijiiwa, K.; Saiki, S.; Shimizu, S.; Tsuneyoshi, M.; Tanaka, M. Reliability of frozen section diagnosis of gallbladder tumor for detecting carcinoma and depth of its invasion. J. Surg. Oncol. 1997, 65, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A.; Gateau, J.; Claussen, J.; Wilhelm, D.; Ntziachristos, V. Optoacoustic imaging of blood perfusion: Techniques for intraoperative tissue viability assessment. J. Biophotonics 2013, 6, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, S.A.; Rybalko, V.Y.; Bigelow, C.E.; Lugade, A.A.; Foster, T.H.; Frelinger, J.G.; Lord, E.M. Preferential attachment of peritoneal tumor metastases to omental immune aggregates and possible role of a unique vascular microenvironment in metastatic survival and growth. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 169, 1739–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, J.A.; Lopez, K.J.; Ceppa, E.P. Mucinous cystic neoplasms of the liver: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management. Hepat. Med. 2023, 15, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Li, F.; Min, R.; Sun, S.; Han, Y.-X.; Feng, Z.-Z.; Li, N. Malignancy risk factors and prognostic variables of pancreatic mucinous cystic neoplasms in Chinese patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 3119–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basturk, O.; Hong, S.-M.; Wood, L.D.; Adsay, N.V.; Albores-Saavedra, J.; Biankin, A.V.; Brosens, L.A.A.; Fukushima, N.; Goggins, M.; Hruban, R.H.; et al. A revised classification system and recommendations from the Baltimore Consensus Meeting for neoplastic precursor lesions in the pancreas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, S.; Khan, L.; Chakraborty, S.; Pai, M.R.; Naik, R. Diagnostic utility, errors and limitations of frozen section in surgical pathology. J. Acad. Med. Param. 2024, 6, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, J.A.; Myers, J.L.; Bostwick, D.G. Accuracy of frozen section diagnosis in surgical pathology: Review of a 1-year experience with 24,880 cases at Mayo Clinic Rochester. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1995, 70, 1137–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namdar, Z.M.; Erdem, B.; Shahabi, S.; Omidifar, N.; Arasteh, P.; Akrami, M.; Tahmasebi, S.; Salehi Nobandegani, A.; Sedighi, S.; Zangouri, V.; et al. How Accurate Is Frozen Section Pathology Compared to Permanent Pathology? World J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 19, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavez, J.A.; Chen, W.; Freitag, C.E.; Frankel, W.L. Pancreatic frozen section guides operative management with few deferrals and errors: Five-year experience at a large academic institution. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2022, 146, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prey, M.U.; Vitale, T.; Martin, S.A. Guidelines for practical utilization of intraoperative frozen sections. Arch. Surg. 1989, 124, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, P.; Deodhar, K.K.; Ramadwar, M.; Bal, M.; Kumar, R.; Goel, M.; Shrikhande, S.V. An audit of frozen sections for suspected gastrointestinal pathology: A three-year institutional study. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.L.; Hsieh, M.S.; Huang, J.Y.; Hsu, P.K.; Lin, C.C.; Huang, M.S.; Yang, C.F.; Jou, H.J.; Wu, C.W. Intraoperative frozen section assessment of esophageal carcinoma margins: Accuracy and clinical impact. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 21, 3032–3038. [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Role of intraoperative frozen section in gastric cancer surgery. Gastric. Cancer 2011, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, D.M. The reliability of frozen-section diagnosis in the pathologic evaluation of Hirschsprung’s disease. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2000, 24, 1675–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsay, V.N.; Basturk, O.; Sakaida, J.; Nakanuma, K.G.; Roa, J.C.; Balci, K.; Aykan, A.; Dogan, S.; Amin, M.B.; Klimstra, D.S. Gallbladder dysplasia and carcinoma: Intraoperative consultation accuracy. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.L. Frozen section diagnosis for axillary sentinel lymph nodes: The first six years. Mod Pathol. 2005, 18, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldblum, J.R.; Hart, W.R. Frozen section evaluation of peritoneal implants: Diagnostic accuracy and pitfalls. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1993, 99, 512–517. [Google Scholar]

- Nakhleh, R.E.; Nosé, V.; Fatheree, L.; Ventura, C.; McCrory, D.; Colasacco, C.; Allen, T.C.; Burgart, L.J.; Fitzgibbons, P.L.; Myers, J.L. Interpretive Diagnostic Error Reduction in Surgical Pathology and Cytology: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center and the Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2015, 140, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelain, D.; Shildknecht, H.; Trouillet, N.; Brasseur, E.; Darrac, I.; Regimbeau, J.-M. Intraoperative consultation in digestive surgery: A consecutive series of 800 frozen sections. J. Visc. Surg. 2012, 149, e134–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, P.A.; Berho, M. Examination of surgical specimens of the esophagus. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2015, 139, 1446–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, G.A.; Wang, K.K.; Lutzke, L.S.; Lewis, J.T.; Sanderson, S.O.; Buttar, N.S.; Wong Kee Song, L.M.; Borkenhagen, L.S.; Burgart, L.J. Frozen section analysis of esophageal endoscopic mucosal resection specimens in the real-time management of Barrett’s esophagus. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 4, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.Q.; Ma, Y.L.; Qin, Q.; Wang, P.H.; Luo, Y.; Xu, P.F.; Cui, Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer in 2020 and projections to 2030 and 2040. Thorac. Cancer 2023, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hihara, J.; Mukaida, H.; Hirabayashi, N. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the esophagus: Current issues of diagnosis, surgery and drug therapy. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, M.; Ilic, I. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 1187–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Ullah, A.; Waheed, A.; Karki, N.R.; Adhikari, N.; Vemavarapu, L.; Belakhlef, S.; Bendjemil, S.M.; Mehdizadeh Seraj, S.; Sidhwa, F. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST): A population-based study using the SEER database. Cancers 2022, 14, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filip, P.V.; Cuciureanu, D.; Diaconu, L.S.; Vladareanu, A.M.; Pop, C.S. MALT lymphoma: Epidemiology, clinical diagnosis and treatment. J. Med. Life 2018, 11, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odze, R.D.; Goldblum, J.R.; Crawford, J.M. Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 309–311. [Google Scholar]

- Lester, S.C.; Fitzgibbons, P.L. Manual of Surgical Pathology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wenig, B.M. Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2016; pp. 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO Classification of Tumours: Digestive System Tumours, 5th ed.; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2019; pp. 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, K.; Yasuda, I.; Hanaoka, T.; Hayashi, Y.; Araki, Y.; Motoo, I.; Kajiura, S.; Ando, T.; Fujinami, H.; Tajiri, K. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy for the diagnosis of gastric linitis plastica. DEN Open 2021, 2, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voutilainen, M.; Juhola, M.; Färkkilä, M.; Sipponen, P. Foveolar hyperplasia at the gastric cardia: Prevalence and associations. J. Clin. Pathol. 2002, 55, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltaggio, L.; Montgomery, E.A. Gastrointestinal tract spindle cell lesions—Just like real estate, it’s all about location. Mod. Pathol. 2015, 28 (Suppl. S1), S47–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbaa, M.A.; Elkady, N.; Abdelrahman, E.M. Predictive factors of positive circumferential and longitudinal margins in early T3 colorectal cancer resection. Int. J. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 6789709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, C.B.; Mahmoud, N.N. Current surgical considerations for colorectal cancer. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galanopoulos, M.; Gkeros, F.; Liatsos, C.; Pontas, C.; Papaefthymiou, A.; Viazis, N.; Mantzaris, G.J.; Tsoukalas, N. Secondary metastatic lesions to colon and rectum. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2018, 31, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.C.; Sokolova, A.; Bettington, M.L.; Rosty, C.; Brown, I.S. Colorectal endometriosis—A challenging, often overlooked cause of colorectal pathology. Pathology 2024, 56, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grüter, A.A.J.; van Lieshout, A.S.; van Oostendorp, S.E.; Ket, J.C.F.; Tenhagen, M.; den Boer, F.C.; Hompes, R.; Tanis, P.J.; Tuynman, J.B. Required distal mesorectal resection margin in partial mesorectal excision: A systematic review on distal mesorectal spread. Tech. Coloproctol. 2023, 27, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, R.M.; Bhandare, M.; Desouza, A.; Bal, M. Role of intraoperative frozen section for assessing distal resection margin after anterior resection. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2015, 30, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shia, J.; McManus, M.; Guillem, J.G.; Leibold, T.; Zhou, Q.; Tang, L.H.; Riedel, E.R.; Weiser, M.R.; Paty, P.B.; Temple, L.K.; et al. Significance of Acellular Mucin Pools in Rectal Carcinoma after Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hissong, E.; Yantiss, R.K. Intraoperative evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract. In Frozen Section Pathology: Diagnostic Challenges; Borczuk, A.C., Yantiss, R.K., Robinson, B.D., Scognamiglio, T., D’Alfonso, T.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 15–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feakins, R.M. Histopathology of non-neoplastic inflammatory bowel disease. In Surgical Pathology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas, 4th ed.; Odze, R.D., Goldblum, J.R., Eds.; Saunders Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 327–349. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H.G.; Nilsson, P.J.; Shogan, B.D.; Harji, D.; Gambacorta, M.A.; Romano, A.; Brandl, A.; Qvortrup, C. Neoadjuvant treatment of colorectal cancer: Comprehensive review. BJS Open 2024, 8, zrae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakha, E.; Ramaiah, S.; McGregor, A. Accuracy of frozen section in the diagnosis of liver mass lesions. J. Clin. Pathol. 2006, 59, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panarelli, N.C.; Yantiss, R.K. Metastases and mimics of colorectal carcinoma. In Frozen Section Library: Appendix, Colon, and Anus; Yantiss, R.K., Panarelli, N.C., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muhsin, M.A.; Sheth, S.; Malick, K.W.; Xu, C.; Nguyen, T.; Mills, S.; Wallace, M.; Singh, R.; Jenkins, R. Accuracy of frozen section in the diagnosis of liver mass lesions: Pitfalls in distinguishing benign biliary lesions from metastatic disease. Histopathology 2008, 53, 467–474. [Google Scholar]

- Pitman, M.B.; Lauwers, G.Y. Fundamental challenges in intraoperative frozen section diagnosis: Artifacts and sampling limitations. In: Frozen Section and the Surgical Pathologist: A Point of View. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2009, 133, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Gandour-Edwards, R.F.; Donald, P.J.; Wiese, D.A. Recommendations for intraoperative frozen section margins, including deferred diagnosis when necessary. In: Accuracy of intraoperative frozen section diagnosis in head and neck surgery: Experience at a university medical center. Head Neck 1993, 15, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjimichael, E.; Fielding, D.E.; Ilyas, M.; Zaitoun, A.M.; Lobo, D.N.; Kaye, P.V. Liver Nodules after Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage: A Case Series. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 3, 1457. [Google Scholar]

- Klöppel, G.; Adsay, N.V. Chronic pancreatitis and the differential diagnosis versus pancreatic cancer. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2009, 133, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuma, K.; Kamisawa, T.; Gopalakrishna, R.; Hara, S.; Tabata, T.; Inaba, Y.; Egawa, N.; Igarashi, Y. Strategy to differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreas cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, K.; Kerem, M.; Bostanci, H.; Sare, M.; Ekinci, O. Intra-operative frozen section histology of the pancreatic resection margins and clinical outcome of patients with adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 4905–4913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adsay, V.; Basturk, O.; Saka, B.; Bagci, P.; Ozdemir, D.; Balci, S.; Kooby, D.; Staley, C.; Maithel, S.; Sarmiento, J.; et al. Whipple Made Simple for Surgical Pathologists: Orientation, Dissection, and Sampling of Pancreaticoduodenectomy Specimens for a More Practical and Accurate Evaluation of Pancreatic, Distal Common Bile Duct, and Ampullary Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014, 38, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cioc, A.M.; Ellison, E.C.; Proca, D.M.; Lucas, J.G.; Frankel, W.L. Frozen section diagnosis of pancreatic lesions. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2002, 126, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distler, M.; Aust, D.E.; Weitz, J.; Pilarsky, C.; Grützmann, R. Precursor lesions for sporadic pancreatic cancer: PanIN, IPMN, and MCN. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 474905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaei, H.; Hong, S.-M.; Mayo, S.C.; dal Molin, M.; Olino, K.; Venkat, R.; Goggins, M.; Herman, J.M.; Edil, B.H.; Wolfgang, C.L. Presence of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia in the pancreatic transection margin after R0 resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Impact on survival. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 440–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, A.; Christopher, W.; Nguyen, T.; Vuong, B.; Stern, S.L.; Mejia, J.; Weerasinghe, R.; Ong, E.; Bilchik, A.J. Routine frozen section during pancreaticoduodenectomy does not improve value-based care. Surg. Pract. Sci. 2022, 10, 100090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenet, T.; Gilbert, R.W.D.; Smoot, R.; Tzeng, C.-W.D.; Rocha, F.G.; Yohanathan, L.; Cleary, S.P.; Martel, G.; Bertens, K.A. Does Intraoperative Frozen Section and Revision of Margins Lead to Improved Survival in Patients Undergoing Resection of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 6748–6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Shirahane, K.; Nakamura, M.; Su, D.; Konomi, H.; Motoyama, K.; Sugitani, A.; Mizumoto, K.; Tanaka, M. Frozen section and permanent diagnoses of the bile duct margin in gallbladder and bile duct cancer. HPB 2005, 7, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangle, N.A.; Taylor, S.L.; Emond, M.; Bronner, M.P.; Overholt, B.F.; Depot, M.F.; Bollschweiler, E.; Sharma, P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Eagan, A. Tangential sectioning artifact creates the appearance of nuclear stratification that may mimic dysplasia. In: Overdiagnosis of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: A multicenter, international study. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraki, T.; Kuroda, H.; Takada, A.; Nakazato, Y.; Kubota, K.; Imai, Y. Intraoperative frozen section diagnosis of bile duct margin for extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 1332–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Bai, J.; Li, Q.; Xu, B.; Dong, Z.; Zhi, X.; Li, T. The Impact of Intraoperative Frozen Section on Resection Margin Status and Survival of Patients Underwent Pancreatoduodenectomy for Distal Cholangiocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 650585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.W.; Blanchard, T.H.; Causey, M.W.; Homann, J.F.; Brown, T.A. Examining the Accuracy and Clinical Usefulness of Intraoperative Frozen Section Analysis in the Management of Pancreatic Lesions. Am. J. Surg. 2013, 205, 613–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igami, T.; Nishio, H.; Ebata, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Sugawara, G.; Nagino, M. Surgical treatment of hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Analysis of 570 consecutive cases in a single center. Ann. Surg. 2013, 258, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, Y.H.; Ko, H.; Go, H.; Park, K.M.; Hur, W.; Kim, Y.T. Recent Advancement in Diagnosis of Biliary Tract Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedj, N.; Sirica, A.E.; Gores, G.J.; Tibesar, R.; Dhanasekaran, R.; Mogal, H.; Pawlik, T.M.; Bridgewater, J.; Rizvi, S. Pathology of Cholangiocarcinomas: Current Concepts and New Insights. Semin. Liver Dis. 2022, 42, 014–032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farges, O.; Regimbeau, J.M.; Fuks, D.; Le Treut, Y.P.; Cherqui, D.; Bachellier, P.; Mabrut, J.Y.; Adham, M.; Pruvot, F.R.; Gigot, J.F. AJCC 7th edition of TNM staging for hilar cholangiocarcinoma: Should we use periductal invasion to define T2 tumors? Ann. Surg. 2011, 253, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amimoto, M.; Kiritoshi, H.; Morimoto, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Ueda, K.; Fujii, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Tajiri, T.; Yamashita, Y. Novel Insights into the Intraepithelial Spread of Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (eCCA) and Clinicopathological Implications. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1216097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooijen, L.E.; Franken, L.C.; de Boer, M.T.; Buttner, S.; van Dieren, S.; Groot Koerkamp, B.; Hoogwater, F.J.H.; Kazemier, G.; Klümpen, H.J.; Kuipers, H. Value of routine intraoperative frozen sections of proximal bile duct margins in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: A retrospective multicenter matched case-control study. HPB 2022, 48, 2424–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, Q.; Wang, B.; Lin, N.; Wang, L.; Liu, J. Does High-Grade Dysplasia/Carcinoma in Situ of the Biliary Duct Margin Affect the Prognosis of Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma? A Meta-Analysis. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 17, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasinskas, A.M. Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2018, 11, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Kondo, S.; Hirano, S.; Ambo, Y.; Tanaka, E.; Morikawa, T.; Okushiba, S.; Katoh, H. Frozen Section Diagnosis of Bile Duct Margins in Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Pitfalls and Clinical Impact. Br. J. Surg. 2004, 91, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Sano, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Esaki, M.; Kosuge, T.; Ojima, H. Intraoperative Frozen Section for Bile Duct Margin Assessment in Bile Duct Cancer and Risk Factors for Recurrence. Br. J. Surg. 2007, 94, 892–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patkar, S.; Gundavda, K.; Chaudhari, V.; Yadav, S.; Deodhar, K.; Ramadwar, M.; Goel, M. Utility and Limitations of Intraoperative Frozen Section Diagnosis to Determine Optimal Surgical Strategy in Suspected Gallbladder Malignancy. HPB 2023, 25, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roa, J.C.; Tapia, O.; Cakir, A.; Basturk, O.; Dursun, N.; Akdemir, D.; Saka, B.; Losada, H.; Bagci, P.; Adsay, V.N. Intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasms (ICPN) of the gallbladder: Clinicopathologic characterization of 123 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2011, 35, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Banh, S.; Fehervari, M.; Flod, S.; Soleimani-Nouri, P.; Leyte Golpe, A.; Ahmad, R.; Pai, M.; Spalding, D.R.C. Single-stage management of suspected gallbladder cancer guided by intraoperative frozen section analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 114, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, A.; Ferris, J.V.; Hosseinzadeh, K.; Roberts, J.P.; Hekimian, K.; Borhani, A.A. Gallbladder carcinoma update: Multimodality imaging evaluation, staging, and treatment options. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2008, 191, 1440–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irrinki, S.; Kumar, P.; Kurdia, K.; Gupta, V.; Mittal, B.R.; Kumar, R.; Das, A.; Yadav, T.D. Missed Gall Bladder Cancer During Cholecystectomy—What Price Do We Pay? Surg. Gastroenterol. Oncol. 2023, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadan, M.; Kingham, T.P. Technical Aspects of Gallbladder Cancer Surgery. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 96, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajal, V.; Nekarakanti, P.K.; K, S.; Nag, H. Effects of Cystic Duct Margin Involvement on the Survival Rates of Patients With Gallbladder Cancer: A Propensity-Score-Matched Case-Control Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e50585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Yin, Y.; Chang, J.; Li, Z.; Bi, X.; Cai, J.; Chen, X. Prognostic Factors and Treatment Outcomes in Gallbladder Cancer Patients: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Curr Oncol. 2025, 32, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Kijima, H.; Imaizumi, T.; Hirabayashi, K.; MatsuYama, M.; Yazawa, N.; Dowaki, S.; Tobita, K.; Ohtani, Y.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Clinical Significance of Wall Invasion Pattern of Subserosa-Invasive Gallbladder Carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adsay, V.; Jang, K.-T.; Roa, J.C.; Dursun, N.; Ohike, N.; Bagci, P.; Basturk, O.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Cheng, J.D.; Sarmiento, J.M. Intracholecystic papillary-tubular neoplasms (ICPN): A distinctive preinvasive neoplasm of the gallbladder resembling intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas and biliary intraepithelial neoplasia. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012, 36, 1279–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, A.; Schumacher, G.; Pascher, A.; Lopez-Hanninen, E.; Al-Abadi, H.; Benckert, C.; Sauer, I.M.; Pratschke, J.; Neumann, U.P.; Jonas, S.; et al. Extended surgical resection for xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking advanced gallbladder carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 2293–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alramadhan, H.J.; Lim, S.-Y.; Jeong, H.-J.; Jeon, H.-J.; Chae, H.; Yoon, S.-J.; Shin, S.-H.; Han, I.-W.; Heo, J.-S.; Kim, H. Different Oncologic Outcomes According to Margin Status (High-Grade Dysplasia vs. Carcinoma) in Patients Who Underwent Hilar Resection for Mid-Bile Duct Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S.; Yoon, G.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Choi, C.-H.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, B.-G.; Bae, D.-S.; Song, S.-Y. Mesothelial Cell Inclusions in Pelvic and Para-aortic Lymph Nodes: A Clinicopathologic Analysis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 5318–5326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clement, P.B.; Young, R.H. Tumors of the peritoneum. In Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors, 5th ed.; Fletcher, C.D.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 1905–1932. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci, M.R.; Oliva, E. Gynecologic Pathology: Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 365–373. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen Van Hung, T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Tran, N.M.; Tran, V.C.; Doan, M.K.; Dao, T.L.; Hoang, T.N.M. Malignancy-Like Subtle Histological Changes and Misdiagnosis Pitfalls in Reactive Enlarged Lymph Nodes. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2023, 10, 5960–5971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Diao, L.; Yang, Z.; Ma, R.; Guo, Q.; Wu, L. Mimicking Dermatopathic Lymphadenitis: An Entity of Lymphoma. Ulus. Hematol. Oncol. Derg. 2017, 27, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Vural, E.; Wenig, B.M.; Hanna, E.Y.; Suen, J.Y.; Cognetti, D.M.; Wasserman, P.G.; Barnes, E.L. What Can We Learn from the Errors in the Frozen Section Diagnosis of Pulmonary Carcinoid Tumors: An Evidence-Based Approach. APMIS 2009, 117, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrović, M.; Veličković, D.; Micev, M.; Sljukić, V.; Đurić, P.; Tadić, B.; Skrobić, O.; Djokić Kovač, J. Encapsulated Omental Necrosis as an Unexpected Postoperative Finding: A Case Report. Medicina 2021, 57, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakrin, N.; Gilly, F.N.; Baratti, D.; Bereder, J.M.; Quenet, F.; Lorimier, G.; Mohamed, F.; Elias, D.; Glehen, O. Primary peritoneal serous carcinoma treated by cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: A multi-institutional study of 36 patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 39, 742–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turra, V.; Manzi, J.; Rombach, S.; Zaragoza, S.; Ferreira, R.; Guerra, G.; Conzen, K.; Nydam, T.; Livingstone, A.; Vianna, R.; et al. Donors with previous malignancy: When is it safe to proceed with organ transplantation? Transpl. Int. 2025, 38, 13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neil, D.A.H.; Minervini, M.; Smith, M.L.; Hubscher, S.G.; Brunt, E.M.; Demetris, A.J.; Brunt, E.M. Banff consensus recommendations for steatosis assessment in donor livers. Hepatology 2022, 75, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da, B.L.; Satiya, J.; Heda, R.P.; Jiang, Y.; Lau, L.F.; Fahmy, A.; Winnick, A.; Roth, N.; Grodstein, E.; Thuluvath, P.J. Outcomes After Liver Transplantation with Steatotic Grafts. Transplantation 2022, 106, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tien, C.; Remulla, D.; Kwon, Y.; Emamaullee, J. Contemporary strategies to assess and manage liver donor steatosis: A review. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2021, 26, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranic, S.; Gatalica, Z. The role of pathology in the era of personalized medicine: A brief review. Acta Med. Acad. 2021, 50, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li Cavoli, T.V.; Curto, A.; Lynch, E.N.; Galli, A. A Narrative Review on De Novo and Donor-Transmitted Cancers in Liver Allograft Recipients. Transplantology 2025, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgos, F.F.; Karakasi, K.-E.; Kofinas, A.; Antoniadis, N.; Katsanos, G.; Tsoulfas, G. Evolving Transplant Oncology: Evolving Criteria for Better Outcomes. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassan, M. Molecular diagnostics in pathology: Time for a next generation pathologist? Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2018, 142, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okojie, J.; O’Neal, N.; Burr, M.; Worley, P.; Packer, I.; Anderson, D.; Davis, J.; Kearns, B.; Fatema, K.; Dixon, K. DNA quantity and quality comparisons between cryopreserved and FFPE tumors from matched pan cancer samples. Unpublished/abstract source incomplete. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2441–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sholl, L.M.; Aisner, D.L.; Varella-Garcia, M.; Ginsberg, M.S.; Aisner, D.L.; Barletta, J.; Otterson, G.A.; Khoubehi, B.; Sequist, L.V.; Heinrich, M.C. Multi-institutional oncogenic driver mutation analysis in lung and colorectal adenocarcinomas: The Lung Cancer Mutation Consortium and GI Mutation Consortium experience. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015, 10, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasteva, N.; Georgieva, M. Promising Therapeutic Strategies for Colorectal Cancer Treatment Based on Nanomaterials. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Luo, S.; Liu, D.; Lu, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, X.; Jia, F.; Pang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zeng, C.; et al. Genomic and transcriptomic landscape of human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N.M.; Tsokos, C.G.; Umetsu, S.E.; Shain, A.H.; Kelley, R.K.; Onodera, C.; Bowman, S.; Talevich, E.; Ferrell, L.D.; Kakar, S. Genomic profiling of combined hepatocellular cholangiocarcinoma reveals similar genetics to hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Pathol. 2019, 248, 164–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.M.; Xian, Z.H. A retrospective analysis of the diagnostic accuracy and technical quality of frozen sections in detecting hepatobiliary lesions. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2022, 61, 152048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, D.; Misra, S.; Chu, P.L.; Guan, P.; Nada, R.; Gupta, R.; Kaewnarin, K.; Ko, T.K.; Heng, H.L.; Srinivasalu, V.K. Cholangiocarcinoma: Recent Advances in Molecular and Histological Profiling. Cancers 2024, 16, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiomi, A.; Kusuhara, M.; Sugino, T.; Sugiura, T.; Ohshima, K.; Nagashima, T.; Urakami, K.; Serizawa, M.; Saya, H.; Yamaguchi, K. Comprehensive genomic analysis contrasting primary colorectal cancer and synchronous colorectal liver metastasis. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 21, 12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuckeroth, R.O. Hirschsprung disease—Integrating basic science and clinical medicine to improve outcomes. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, R.P. Pathology of Hirschsprung disease and related disorders. Surg. Pathol. Clin. 2010, 3, 371–397. [Google Scholar]

- Teitelbaum, D.H.; Coran, A.G. Hirschsprung’s disease and related neuromuscular disorders of the intestine. In Ashcraft’s Pediatric Surgery, 6th ed.; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 468–490. [Google Scholar]

- Cserni, G. Histopathological pitfalls in the evaluation of suction rectal biopsies for Hirschsprung’s disease. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2006, 12, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, P.; Shinkai, M. Pathophysiology of the enteric nervous system in Hirschsprung disease. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2004, 20, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, S.A.; Smith, B.H.; Younger, M.; Horn, P.; Heys, M.; Puri, P. Does the absence of hypertrophic nerves on rectal biopsy predict long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis? Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2025, 41, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Miyahara, K.; Kusafuka, J.; Yamataka, A.; Lane, G.J.; Sueyoshi, N.; Miyano, T.; Puri, P. A New Rapid Acetylcholinesterase Staining Kit for Diagnosing Hirschsprung’s Disease. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2007, 23, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, S.; Ikeda, K.; Toyohara, T. When Is the Optimal Diagnostic Biopsy Timing of Acetylcholinesterase Staining in Hirschsprung Disease? Clin. Anat. 2025, 38, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Jung, H.R.; Hwang, I.; Kwon, S.Y.; Choe, M.; Kang, Y.N.; Jung, E.; Kim, S.P. Diagnostic Accuracy of Combined Acetylcholinesterase Histochemistry and Calretinin Immunohistochemistry of Rectal Biopsy Specimens in Hirschsprung’s Disease. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 26, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lok, M.J.; Noordam, C.; de Lorijn, F.; Aronson, D.C.; Westra, D.F.; Kemp, R.; Wong, N.; Heij, H.A. Development of Nerve Fibre Diameter in Young Infants With Hirschsprung Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2018, 66, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaides, S.; Boussioutas, A. Immune-Related Adverse Events of the Gastrointestinal System. Cancers 2023, 15, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casagrande, S.; Sopetto, G.B.; Bertalot, G.; Bortolotti, R.; Racanelli, V.; Caffo, O.; Giometto, B.; Berti, A.; Veccia, A. Immune-Related Adverse Events Due to Cancer Immunotherapy: Immune Mechanisms and Clinical Manifestations. Cancers 2024, 16, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Zhu, K.; Zhang, J.; Joshi, U.; Liu, H.; Zahid, S.; Jadhav, N.; Okolo, P.I., 3rd. Analysis of immune-related adverse events in gastrointestinal malignancy patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int. J. Cancer 2024, 154, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, T.W.; Slaw, R.J.; McKenney, J.K. Telepathology in Frozen Section Diagnosis: A Systematic Review of Current Practices. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2021, 156, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, D.; Ma, L.; Guo, L.; Tang, M.; Liu, G.; Yan, Q.; Shen, L.; et al. Telepathology consultation for frozen section diagnosis in China. Diagn. Pathol. 2018, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccher, A.; Marletta, S.; Sbaraglia, M.; Guerriero, A.; Rossi, M.; Gambaro, G.; Scarpa, A.; Dei Tos, A.P. Digital pathology structure and deployment in Veneto: A proof-of-concept study. Virchows Archiv. 2024, 485, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.B.; Patel, K.; Gupta, R. Diagnostic Concordance in Telepathology-Based Frozen Section Consultation: A Five-Year Institutional Experience. Hum. Pathol. 2022, 127, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D.E.; Jenkins, S.M.; Voss, J.S. Large-Scale Telepathology Implementation for Frozen Section Coverage: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 2134–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, S.; Park, S.H. Workflow Integration of Telepathology Systems in Modern Surgical Pathology Practice. J. Pathol. Inform. 2023, 14, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, D.F.; Nagpal, K.; Sayres, R.; Foote, D.J.; Wedin, B.D.; Pearce, A.; Cai, C.J.; Winter, S.R.; Symonds, M.; Yatziv, L.; et al. Evaluation of combined artificial intelligence and pathologist assessment to review and grade prostate biopsies. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2023267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campanella, G.; Hanna, M.G.; Geneslaw, L.; Miraflor, A.; Krauss, V.W.; Busam, K.J.; Brogi, E.; Reuter, V.E.; Klimstra, D.S.; Fuchs, T.J. Clinical-Grade Computational Pathology Using Weakly Supervised Deep Learning on Whole Slide Images. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, L.; Cai, M. A multicenter proof-of-concept study on deep learning-based intraoperative discrimination of primary CNS lymphoma. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Zheng, K.; Wen, Y.; Meng, J.; Zhang, X.; Wen, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zheng, C.; Cai, X.; Lin, J. An end-to-end multifunctional AI platform for intraoperative diagnosis. Npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, C.A.; Zhang, J. (Eds.) Recent Applications of Machine Learning in Natural Language Processing (NLP); MDPI Books; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2025; ISBN 978-3-7258-4533-0 (Hardback)/978-3-7258-4534-7 (PDF). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigdorovits, A.; Köteles, M.M.; Olteanu, G.-E.; Pop, O. Breaking Barriers: AI’s Influence on Pathology and Oncology in Resource-Scarce Medical Systems. Cancers 2023, 15, 5692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, D.F.; MacDonald, R.; Liu, Y.; Truszkowski, P.; Hipp, J.D.; Gammage, C.; Thng, F.; Peng, L.; Stumpe, M.C. Impact of Deep Learning Assistance on the Histopathologic Review of Lymph Nodes for Metastatic Breast Cancer. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2018, 42, 1636–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloy, C. (Ed.) Digital Pathology: Records of Successful Implementations; MDPI Books; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-3-7258-2038-2 (Hardback)/978-3-7258-2037-5 (PDF). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, R.S. Prospects for telepathology. Hum. Pathol. 2020, 96, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Janabi, S.; Huisman, A.; Vink, A.; Leguit, R.J.; Offerhaus, G.J.A.; ten Kate, F.J.W.; van Diest, P.J. Whole slide images for primary diagnostics of gastrointestinal tract biopsies: A feasibility study. Hum. Pathol. 2012, 43, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulten, W.; Balkenhol, M.; Belinga, J.J.A.; Brilhante, A.; Çakır, A.; Egevad, L.; Eklund, M.; Farré, X.; Geronatsiou, K.; Molinié, V. Artificial intelligence assistance significantly improves Gleason grading of prostate biopsies by pathologists. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 34, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashshur, R.L.; Krupinski, E.A.; Weinstein, R.S.; Dunn, M.R.; Bashshur, N. The Empirical Foundations of Telepathology: Evidence of Feasibility and Intermediate Effects. Telemed. J. e-Health 2017, 23, 155–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Clinical Evaluation—Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/100714/download (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Petersen, J.M.; Jhala, N.; Jhala, D.N. The Critical Value of Telepathology in the COVID-19 Era. Fed. Pr. 2023, 40, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, K.E.; Georgiou, E.; Satava, R.M. 5G Use in Healthcare: The Future is Present. JSLS 2021, 25, e2021.00064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, A.H.; Jaume, G.; Williamson, D.F.K.; Lu, M.Y.; Vaidya, A.; Miller, T.R.; Mahmood, F. Artificial Intelligence for Digital and Computational Pathology. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2401.06148v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organ | Reported Sensitivity/Specificity | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Oesophagus [48] | Sensitivity 90–95%, Specificity 98–100% | Tangential margins, cautery artefacts |

| Stomach [49] | Sensitivity 92–96%, Specificity 97–99% | Poor differentiation, frozen artefacts |

| Colon/Hirschsprung [50] | Sensitivity 90–95%, Specificity 95–98% | Inadequate submucosa sampling, immature ganglion cells |

| Liver [35] | Sensitivity 85–95%, Specificity 95–99% | Sampling error in well-differentiated HCC, freezing artefacts |

| Pancreas [35] | Sensitivity 80–90%, Specificity 95–98% | Chronic pancreatitis vs. adenocarcinoma, scant samples |

| Gallbladder [51] | Sensitivity 88–94%, Specificity 96–99% | Tangential cuts, flat dysplasia vs. reactive atypia |

| Lymph nodes [52] | Sensitivity 85–95%, Specificity >98% | Micrometastases may be missed |

| Peritoneum [53] | Sensitivity 90–96%, Specificity 98–100% | Necrotic tissue, scant cellularity |

| Feature | Bile Duct Adenoma | Bile Duct Hamartoma |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Usually solitary, subcapsular | Multiple, scattered throughout the liver parenchyma |

| Size | Small (<1.5 cm), usually <1 cm | Small (<0.5 cm), often <0.3 cm |

| Gross Appearance | Well-circumscribed, firm nodule | Multiple, tiny white-grey nodules |

| Architecture | Compact proliferation of small ducts in fibrous stroma | Dilated, irregular ducts in fibrous stroma |

| Cystic dilatation | Rare | Common (dilated, sometimes cystic ducts) |

| Lining epithelium | Cuboidal, bland biliary-type cells | Flattened to cuboidal, bland biliary epithelium |

| Stroma | Prominent fibrous stroma | Abundant fibrous stroma with possible calcifications |

| Portal tracts | Absent | May be associated with distorted portal areas |

| Bile production | Typically absent | May contain bile pigment |

| Features | PDAC | Chronic Pancreatitis/AIP |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Haphazard, irregularly infiltrative glands, loss of lobular architecture | Preserved or distorted lobular architecture, fibrosis around ducts rather than an infiltrating pattern |

| Glandular features | Angulated, atypical glands, irregular contours, often naked glands in desmoplastic stroma | Ducts often surrounded by onion-skin fibrosis (esp. AIP), no significant atypia |

| Cytological atypia | Moderate to marked nuclear atypia, nuclear irregularity, prominent nucleoli, mitoses | Minimal cytologic atypia, if any; bland ductal epithelium |

| Stromal response | Desmoplastic stroma, myxoid to sclerotic; often devoid of inflammatory cells | Cell-rich storiform fibrosis, particularly in AIP, often plasma cell-rich |

| Perineural invasion | Often present | Rare to absent |

| Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates | Mild to absent | Dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, especially in AIP |

| Venous invasion | Common in PDAC | Absent in CP |

| Duct rupture of obliteration | Not characteristic | Duct-centric obliterative phlebitis and duct destruction typical in AIP |

| Serum markers | Often ↑ CA19.9 (non-specific) | ↑ Serum IgG4 (in AIP type 1), normal CA19.9 |

| Imaging | Hypoenhancing mass on CT/MRI, ductal cutoff, double duct sign | Diffuse or segmental enlargement (“sausage-shaped pancreas”), capsule-like rim (AIP) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaitoun, A.M.; Almahari, S.A. Frozen Section Studies of Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Systems: A Review Article. Gastroenterol. Insights 2025, 16, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent16040046

Zaitoun AM, Almahari SA. Frozen Section Studies of Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Systems: A Review Article. Gastroenterology Insights. 2025; 16(4):46. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent16040046

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaitoun, Abed M., and Sayed Ali Almahari. 2025. "Frozen Section Studies of Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Systems: A Review Article" Gastroenterology Insights 16, no. 4: 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent16040046

APA StyleZaitoun, A. M., & Almahari, S. A. (2025). Frozen Section Studies of Gastrointestinal and Hepatobiliary Systems: A Review Article. Gastroenterology Insights, 16(4), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/gastroent16040046