Senotherapeutics for Brain Aging Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cellular Senescence and the Aging Brain

| Topic | Key Concept | Implications for Brain Aging | Current Challenges |

Future Directions & Potential Solutions | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical view of senescence | Irreversible cell cycle arrest in proliferative cells (e.g., fibroblasts) due to damage, telomere attrition, or oncogene activation. | Protective short-term (tumor suppression); harmful long-term due to accumulation. | Oversimplified view; ignores senescence in non-dividing cells like neurons and glia. |

Expand definition to include post-mitotic senescence, focusing on metabolic and secretory dysfunction. | [66] |

| Expanded view (CNS involvement) |

Senescence occurs in non- and slowly dividing CNS cells (neurons, astrocytes, microglia, OPCs, endothelial cells). | Disrupts cellular metabolism, intercellular communication, and neural network function. | Difficult to distinguish from other age-related dysfunctions; lack of CNS-specific markers. | Develop and validate cell-type-specific senescence biomarkers and non-invasive imaging techniques (e.g., PET tracers for p16). | [67] |

| SASP |

Secretion of pro-inflammatory factors (IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α), proteases (MMPs), growth factors, and reactive oxygen species (ROS). | Drives chronic neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and disrupts the neural environment. | The SASP is heterogeneous; some components may have context-dependent beneficial roles. | Develop next-generation senomorphics that selectively inhibit harmful SASP factors while preserving beneficial tissue-repair functions. | [68] |

| Paracrine Spreading | SASP factors and extracellular vesicles transmit the senescent phenotype to neighboring healthy cells (“bystander effect”). | Creates a feed-forward cycle, amplifying tissue damage and accelerating functional decline. | Hard to block systemic/paracrine signaling without causing off-target effects on healthy cells. | Develop localized delivery systems (nanoparticles) and agents that neutralize specific SASP factors or block their receptors. | [69] |

|

Impact on Plasticity |

Senescent cells reduce neural stem cell (NSC) regeneration and impair synaptic remodeling. | Loss of brain plasticity accelerates cognitive impairment and hinders recovery from injury. | Limited innate regenerative capacity in the adult human brain. | Combine senotherapeutics with pro-regenerative interventions (e.g., NSC transplantation, neurotrophic factors). | [56] |

| BBB Integrity |

Senescent endothelial cells and pericytes increase blood–brain barrier permeability. | Allows infiltration of harmful peripheral molecules and immune cells, linked to vascular cognitive impairment. | Targeting vascular senescence without compromising systemic vascular health or causing toxicity. | Design endothelial-specific senolytics and utilize nanoparticle-based delivery to target the cerebrovasculature. | [70] |

|

Therapeutic Implications |

Senolytics clear senescent cells; Senomorphics suppress the SASP. | Preclinical evidence shows reduced neuroinflammation, improved proteostasis, and enhanced cognition. | Risk of off-target effects; incomplete clearance; long-term safety unknown. | Optimize therapy with refined senolytic cocktails, intermittent dosing regimens, and personalized medicine based on biomarker profiles. | [71] |

3. Senotherapeutics: Classification and Mechanisms

3.1. Senolytics: Selective Clearance of Senescent Cells

| Senolytic Agent | Primary Target/ Mechanism | Key Effects | Notes/Limitations | Clinical Implementations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dasatinib (D) | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor; disrupts SCAP signaling pathways | Clearance of senescent adipose, endothelial, and glial cells | Approved for leukemia; repurposed as senolytic; systemic off-target effects | Pilot clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and other age-related conditions | [75] |

| Quercetin (Q) | Flavonoid; modulates PI3K/AKT and other pro-survival signaling | Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and senolytic activity | Natural dietary compound; limited bioavailability and BBB penetration | Used in combination with dasatinib in early-phase clinical studies | [14] |

| D + Q Combination | Synergistic targeting of multiple SCAPs | Reduces senescent glial cells, decreases neuroinflammation, improves cognition; decreases tau and amyloid-β burden | Synergistic effect stronger than single agents | Ongoing clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease, frailty, kidney disease, and other age-related disorders | [76] |

| Navitoclax (ABT-263) | BCL-2 and BCL-XL inhibition | Potent induction of apoptosis in senescent cells | Dose-limiting thrombocytopenia due to platelet dependence on BCL-XL | Investigated in oncology; limited senolytic clinical use due to toxicity | [77] |

| FOXO4-DRI Peptide | Disrupts FOXO4–p53 interaction | Triggers apoptosis selectively in senescent cells; spares normal cells | Experimental; limited in vivo data so far | Preclinical stage; potential applications in neurodegeneration and cancer | [78] |

| Emerging strategies (nanocarriers, brain-penetrant prodrugs) | Targeted delivery platforms; enhanced BBB permeability | Improve selectivity and efficacy of senolytic agents | Early development; preclinical research phase | Not yet in clinical trials; potential to optimize CNS-targeted senolytic therapies | [79] |

3.2. Senomorphics: Modulating Senescent Cell Behaviour

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier/ Reference | Condition | Intervention | Phase | Primary Outcomes/Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04785300/[92] |

Mild Alzheimer’s Disease |

Dasatinib + Quercetin (D + Q) | 1 |

Feasibility and safety established; reduction in senescence and inflammation biomarkers in blood and CSF observed. |

| NCT04685590/[93] | Older Adults at Risk for AD |

Dasatinib + Quercetin (D + Q) | Pilot | Improvement in cognitive and mobility measures compared to placebo. |

| NCT04313634 [94] |

Diabetic Kidney

Disease |

Dasatinib + Quercetin (D + Q) | 1 | Ongoing; assessing safety and senescence biomarkers. |

| [95,96] | Healthy Elderly | Fisetin | 2 | Completed; results pending on safety and biomarkers of senescence and inflammation. |

| NCT04511416 [97] | Diabetes and Cognitive Decline | Metformin | N/A | Meta-analyses associate metformin use with a significantly reduced risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. |

| RTB-101-204 [98] | Aging | RTB101 (mTOR inhibitor) | 2 | Completed; reduced incidence of respiratory tract infections. |

3.3. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence

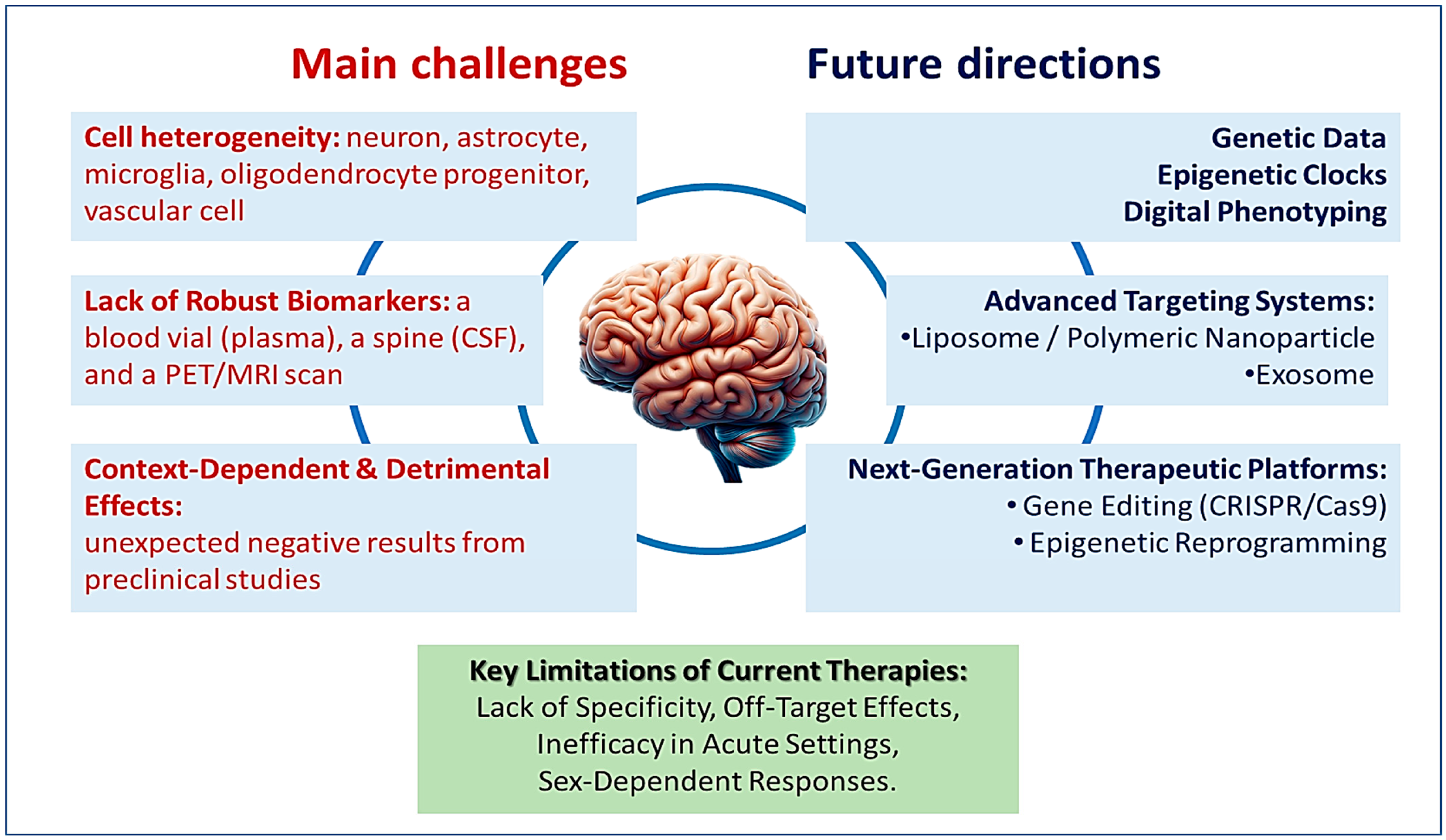

4. Challenges and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, E.E.; Biessels, G.J.; Gao, V.; Gottesman, R.F.; Liesz, A.; Parikh, N.S.; Iadecola, C. Systemic determinants of brain health in ageing. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2024, 20, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yang, J.; Hou, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L. Global, regional, and national health inequalities of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease in 204 countries, 1990–2019. Int. J. Equity Health 2024, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy, C.P.; Pei, J.; Alugoju, P.; Anthikapalli, N.V.A.; Jayaraman, S.; Veeraraghavan, V.P.; Gopathy, S.; Roy, J.R.; Janaki, C.S.; Thalamati, D.; et al. New strategies of neurodegenerative disease treatment with extracellular vesicles (EVs) derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Theranostics 2023, 13, 4138–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, M.P.; Ranjit, R.; Owen, D.B.; Wilson, J.L.; Stiles, M.A.; Masingale, A.M.; Thomas, Z.; Bredegaard, A.; Sherry, D.M.; Logan, S. Cellular Senescence Is a Central Driver of Cognitive Disparities in Aging. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budamagunta, V.; Kumar, A.; Rani, A.; Bean, L.; Manohar-Sindhu, S.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, D.; Foster, T.C. Effect of peripheral cellular senescence on brain aging and cognitive decline. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; Demaria, M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Du, Y.; Hao, S.; Ni, T. The Regulation of Cellular Senescence in Cancer. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, M.M.; Garbarino, V.R.; Zilli, E.M.; Petersen, R.C.; Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T.; Musi, N.; Seshadri, S.; Craft, S.; Orr, M.E. Senolytic Therapy to Modulate the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease (SToMP-AD): A Pilot Clinical Trial. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 9, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Evans, S.A.; Fielder, E.; Victorelli, S.; Kruger, P.; Salmonowicz, H.; Weigand, B.M.; Patel, A.D.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Whole-body senescent cell clearance alleviates age-related brain inflammation and cognitive impairment in mice. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, M.; Shimizu, I.; Katsuumi, G.; Yoshida, Y.; Hayashi, Y.; Ikegami, R.; Matsumoto, N.; Yoshida, Y.; Mikawa, R.; Katayama, A.; et al. Senolytic vaccination improves normal and pathological age-related phenotypes and increases lifespan in progeroid mice. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 1117–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo dos Santos, L.S.; Trombetta-Lima, M.; Eggen, B.J.L.; Demaria, M. Cellular senescence in brain aging and neurodegeneration. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93, 102141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccardi, V.; Orr, M.E.; Polidori, M.C.; Ruggiero, C.; Mecocci, P. Focus on senescence: Clinical significance and practical applications. J. Intern. Med. 2024, 295, 599–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J.H.; Han, H.J. Senotherapeutics: Different approaches of discovery and development. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Tuday, E.; Allen, S.; Kim, J.; Trott, D.W.; Holland, W.L.; Donato, A.J.; Lesniewski, L.A. Senolytic drugs, dasatinib and quercetin, attenuate adipose tissue inflammation, and ameliorate metabolic function in old age. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e13767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, E.; Kantarjian, H. Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2025 update on diagnosis, therapy, and monitoring. Am. J. Hematol. 2024, 99, 2191–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Agustín, A.; Casanova, V.; Grau-Expósito, J.; Sánchez-Palomino, S.; Alcamí, J.; Climent, N. Immunomodulatory Activity of the Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Dasatinib to Elicit NK Cytotoxicity against Cancer, HIV Infection and Aging. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichaiyo, S.; Svasti, S.; Maiuthed, A.; Rukthong, P.; Goli, A.S.; Morales, N.P. Dasatinib Ointment Promotes Healing of Murine Excisional Skin Wound. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachota, M.; Siernicka, M.; Pilch, Z.; Graczyk-Jarzynka, A.; Winiarska, M. Dasatinib Effect on NK Cells and Anti-Tumor Immunity. Blood 2018, 132, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.-C.; Cheng, H.-I.; Hsu, K.; Hsu, Y.-N.; Kao, C.-W.; Chang, Y.-F.; Lim, K.-H.; Chen, C.G. NKG2A Down-Regulation by Dasatinib Enhances Natural Killer Cytotoxicity and Accelerates Effective Treatment Responses in Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Front. Immunol. 2019, 9, 3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondonno, N.P.; Dalgaard, F.; Kyrø, C.; Murray, K.; Bondonno, C.P.; Lewis, J.R.; Croft, K.D.; Gislason, G.; Scalbert, A.; Cassidy, A.; et al. Flavonoid intake is associated with lower mortality in the Danish Diet Cancer and Health Cohort. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okselni, T.; Septama, A.W.; Juliadmi, D.; Dewi, R.T.; Angelina, M.; Yuliani, T.; Saragih, G.S.; Saputri, A. Quercetin as a therapeutic agent for skin problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis on antioxidant effects, oxidative stress, inflammation, wound healing, hyperpigmentation, aging, and skin cancer. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 5011–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Gao, D.; Wang, T.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S. From nature to clinic: Quercetin’s role in breast cancer immunomodulation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1483459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, A.; Lukinich-Gruia, A.T.; Cristea, I.M.; Pricop, M.A.; Calma, C.L.; Simina, A.G.; Tatu, C.A.; Galuscan, A.; Paunescu, V. Quercetin and Mesenchymal Stem Cell Metabolism: A Comparative Analysis of Young and Senescent States. Molecules 2024, 29, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Martinez, E.J.; Flores-Hernández, F.Y.; Salazar-Montes, A.M.; Nario-Chaidez, H.F.; Hernández-Ortega, L.D. Quercetin, a Flavonoid with Great Pharmacological Capacity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frenț, O.-D.; Stefan, L.; Morgovan, C.M.; Duteanu, N.; Dejeu, I.L.; Marian, E.; Vicaș, L.; Manole, F. A Systematic Review: Quercetin—Secondary Metabolite of the Flavonol Class, with Multiple Health Benefits and Low Bioavailability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Subramanian, A.; Kumarasamy, V.; Tamilanban, T.; Begum, M.Y.; Sekar, M.; Subramaniyan, V.; Gan, S.H.; Wong, L.S.; Al Fatease, A.; et al. Network Pharmacology of Natural Polyphenols for Stroke: A Bioinformatic Approach to Drug Design. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. 2024, 17, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Ding, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, B.; Zhang, T. Quercetin Attenuates MRGPRX2-Mediated Mast Cell Degranulation via the MyD88/IKK/NF-kappaB and PI3K/AKT/Rac1/Cdc42 Pathway. J. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 17, 7099–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Qingman, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, D.; Liu, S. Quercetin as a Multi-Target Natural Therapeutic in Aging-Related Diseases: Systemic Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 4821–4869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granieri, M.C.; Rocca, C.; De Bartolo, A.; Nettore, I.C.; Rago, V.; Romeo, N.; Ceramella, J.; Mariconda, A.; Macchia, P.E.; Ungaro, P.; et al. Quercetin and Its Derivative Counteract Palmitate-Dependent Lipotoxicity by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Cardiomyocytes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, H.; Li, W.; Zhou, X. Quercetin promotes locomotor function recovery and axonal regeneration through induction of autophagy after spinal cord injury. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2021, 48, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Wen, L.; Ling, Z.; Xia, J.; Cheng, B.; Peng, J. Quercetin ameliorates senescence and promotes osteogenesis of BMSCs by suppressing the repetitive element-triggered RNA sensing pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 55, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iswarya, B.R.; John, C.M. Modulating senescence-associated secretory phenotype–driven paracrine effects to overcome therapy-induced senescence: Senolytic effects of hesperidin and quercetin in A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqahtani, S.; Alqahtani, T.; Venkatesan, K.; Sivadasan, D.; Ahmed, R.; Sirag, N.; Elfadil, H.; Abdullah Mohamed, H.; T.A., H.; Elsayed Ahmed, R.; et al. SASP Modulation for Cellular Rejuvenation and Tissue Homeostasis: Therapeutic Strategies and Molecular Insights. Cells 2025, 14, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.K.; Banarjee, R.; Boroumand, M.; Rutherford, D.V.; Strassheim, Q.; Nyunt, T.; Olinger, B.; Basisty, N. Translating Senotherapeutic Interventions into the Clinic with Emerging Proteomic Technologies. Biology 2023, 12, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P.; Duan, X.; Li, L.; Zhou, P.; Zou, C.G.; Xie, K. Cellular senescence in cancer: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. MedComm 2024, 5, e542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, B.; Jovanovic, I.; Stojanovic, M.D.; Stojanovic, B.S.; Kovacevic, V.; Radosavljevic, I.; Jovanovic, D.; Kovacevic, M.M.; Zornic, N.; Arsic, A.A.; et al. Oxidative Stress-Driven Cellular Senescence: Mechanistic Crosstalk and Therapeutic Horizons. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lomeli, I.; Kron, S.J. Therapy-Induced Cellular Senescence: Potentiating Tumor Elimination or Driving Cancer Resistance and Recurrence? Cells 2024, 13, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Acosta, J.C.; Adams, P.D.; di Fagagna, F.D.; Baker, D.J.; Bishop, C.L.; Chandra, T.; Collado, M.; Gil, J.; Gorgoulis, V.; et al. Guidelines for minimal information on cellular senescence experimentation in vivo. Cell 2024, 187, 4150–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcozzi, S.; Bigossi, G.; Giuliani, M.E.; Giacconi, R.; Piacenza, F.; Cardelli, M.; Brunetti, D.; Segala, A.; Valerio, A.; Nisoli, E.; et al. Cellular senescence and frailty: A comprehensive insight into the causal links. GeroScience 2023, 45, 3267–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, D.J.; Zhang, J.X.; Fang, X.; Wang, X.Y.; He, X.; Shu, X. Expression and potential regulatory mechanism of cellular senescence-related genes in Alzheimer’s disease based on single-cell and bulk RNA datasets. Front. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1595847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Medrano, J.; Sotelo, D.; Vidal Martinez, G.; Thompson, P.M. Exploratory study of the dysregulation of age-related changes in neural/glial antigen 2 and neuroinflammation markers in individuals with major depression. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2025, 49, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looprasertkul, S.; Yamazaki, R.; Osanai, Y.; Ohno, N. Reduced Accumulation Rate and Morphological Changes of Newly Generated Myelinating Oligodendrocytes in the Corpus Callosum of Aged Mice. Glia 2025, 73, 2322–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; Nie, L.; Zhao, P.; Ji, N.; Liao, G.; Wang, Q. Senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its impact on oral immune homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1019313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-Souto, V.; Da Silva-Álvarez, S.; Collado, M. The role of extracellular vesicles in cellular senescence. FEBS J. 2022, 290, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yu, H.; Xu, Y. Targeting Cellular Senescence: Pathophysiology in Multisystem Age-Related Diseases. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, S.; Senapati, S.; Haque, M.A.; Kayed, R. Senescence, brain inflammation, and oligomeric tau drive cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: Evidence from clinical and preclinical studies. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 20, 709–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, P.S.; Durán-Laforet, V.; Ho, L.T.; Melchor, G.S.; Zia, S.; Manavi, Z.; Barclay, W.E.; Lee, S.H.; Shults, N.; Selva, S.; et al. Senescent-like microglia limit remyelination through the senescence associated secretory phenotype. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Valbuena, I.; Fullam, S.; O’Dowd, S.; Tartaglia, M.C.; Kovacs, G.G. α-Synuclein seed amplification assay positivity beyond synucleinopathies. eBioMedicine 2025, 120, 105925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.M.; Talwar, P. Amyloid-β, Tau, and α-Synuclein Protein Interactomes as Therapeutic Targets in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, R.; Iyaswamy, A.; Krishnamoorthi, S.; Thakur, A.; Durairajan, S.S.K.; Yang, C.; Wankhar, D. Current aspects of targeting cellular senescence for the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1627921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda-Carrasco, J.; Martin-Bermejo, M.J.; Pereyra, G.; Mateo, M.I.; Borroto, A.; Brosseron, F.; Kummer, M.P.; Schwartz, S.; López-Atalaya, J.P.; Alarcon, B.; et al. SFRP1 modulates astrocyte-to-microglia crosstalk in acute and chronic neuroinflammation. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e51696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, C.E.; Pallais, J.P.; McGonigle, S.; Mansk, R.P.; Collinge, C.W.; Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Baker, D.J.; Schrank, P.R.; Williams, J.W.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; et al. Chronic social stress induces p16-mediated senescent cell accumulation in mice. Nat. Aging 2024, 5, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safwan-Zaiter, H.; Wagner, N.; Wagner, K.-D. P16INK4A—More Than a Senescence Marker. Life 2022, 12, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Misawa, T.; Hitomi, K.; Miyata, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Fujii, R.; Chiba, M.; Loo, T.M.; Hanyu, A.; Kawasaki, H.; Kato, H.; et al. Identification of Novel Senescent Markers in Small Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.; Moreira, J.A.F.; Santos, S.S.; Solá, S. Sustaining Brain Youth by Neural Stem Cells: Physiological and Therapeutic Perspectives. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 8222–8247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duve, K.; Lushchak, V.; Shkrobot, S. Aging of neural stem cells and vascular dysfunction: Mechanisms, interconnection, and therapeutic perspectives. Cereb. Circ.-Cogn. Behav. 2025, 9, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulej, R.; Patai, R.; Ungvari, A.; Kallai, A.; Tarantini, S.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Huffman, D.M.; Conboy, M.J.; Conboy, I.M.; Kivimäki, M.; et al. Impacts of systemic milieu on cerebrovascular and brain aging: Insights from heterochronic parabiosis, blood exchange, and plasma transfer experiments. Geroscience 2025, 47, 6207–6376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, H.; Shen, X.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D. The role of cellular senescence in metabolic diseases and the potential for senotherapeutic interventions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1276707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, O.W.; de Aguiar, M.S.S.; de Mello, J.E.; Alvez, F.L.; Luduvico, K.P.; Garcia, D.N.; Schneider, A.; Masternak, M.M.; Spanevello, R.M.; Stefanello, F.M. Senolytics prevent age-associated changes in female mice brain. Neurosci. Lett. 2024, 826, 137730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungvari, A.; Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Patai, R.; Csik, B.; Gulej, R.; Nagy, D.; Shanmugarama, S.; Benyó, Z.; Kiss, T.; Ungvari, Z.; et al. Cerebromicrovascular senescence in vascular cognitive impairment: Does accelerated microvascular aging accompany atherosclerosis? Geroscience 2025, 47, 5511–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csik, B.; Nyúl-Tóth, Á.; Gulej, R.; Patai, R.; Kiss, T.; Delfavero, J.; Nagaraja, R.Y.; Balasubramanian, P.; Shanmugarama, S.; Ungvari, A.; et al. Senescent Endothelial Cells in Cerebral Microcirculation Are Key Drivers of Age-Related Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption, Microvascular Rarefaction, and Neurovascular Coupling Impairment in Mice. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Wei, Z.; Nielsen, J.S.; Ouyang, Y.; Kakazu, A.; Wang, H.; Du, L.; Li, R.; Chu, T.; Scafidi, S.; et al. Senolytic therapy preserves blood-brain barrier integrity and promotes microglia homeostasis in a tauopathy model. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 202, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessland, M.; Ximerakis, M.; Jarjour, A.A.; Zhang, B.; Orr, M.E. Therapeutic targeting of senescent cells in the CNS. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2024, 23, 817–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichim, T.E.; Ramos, R.A.; Rath, A.; Castellano, J.; Azimi, N.; Veltmeyer, J.D.; Koumjian, M.; Ma, N.E.; Bajnath, A.; Lin, E.; et al. Reversing coma by senolytics and stem cells: The future is now. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, L.; Ramponi, V.; Gupta, K.; Stevenson, T.; Mathew, A.B.; Barinda, A.J.; Herbstein, F.; Morsli, S. Emerging insights in senescence: Pathways from preclinical models to therapeutic innovations. npj Aging 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Jat, P. Mechanisms of Cellular Senescence: Cell Cycle Arrest and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 645593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, H.R.; Sun, X.; Orr, M.E. Senescent brain cell types in Alzheimer’s disease: Pathological mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Neurotherapeutics 2025, 22, e00519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Li, K.; Li, Q.; Tong, Q.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L. The controversial role of senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in cancer therapy. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polzer, O.; Kinloch, E.; Fitzsimons, C.P. Cellular senescence, neuroinflammation, and microRNAs: Possible interactions driving aging and neurodegeneration in the hippocampal neurogenic niche. Aging Brain 2025, 8, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopp, R.C.; Erickson, M.A.; Rhea, E.M.; Reed, M.J.; Banks, W.A. Cellular senescence and the blood–brain barrier: Implications for aging and age-related diseases. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Targeting Senescence: A Review of Senolytics and Senomorphics in Anti-Aging Interventions. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Yamamoto, S.; Chikenji, T.S. Role of cellular senescence in inflammation and regeneration. Inflamm. Regen. 2024, 44, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’Hôte, V.; Mann, C.; Thuret, J.-Y. From the divergence of senescent cell fates to mechanisms and selectivity of senolytic drugs. Open Biol. 2022, 12, 220171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, R.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Lemaitre, J.-M. Emerging Therapeutic Approaches to Target the Dark Side of Senescent Cells: New Hopes to Treat Aging as a Disease and to Delay Age-Related Pathologies. Cells 2023, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Prahalad, V.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS J. 2022, 290, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakubo, S.; Abe, H.; Li, Y.; Kudo, M.; Kimura, A.; Wakabayashi, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Kimura, N.; Setsu, T.; Yokoo, T.; et al. Dasatinib and Quercetin as Senolytic Drugs Improve Fat Deposition and Exhibit Antifibrotic Effects in the Medaka Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Model. Diseases 2024, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, K.; Ishii, T.; Asou, T.; Kishi, K. Navitoclax (ABT-263) Rejuvenates Human Skin by Eliminating Senescent Dermal Fibroblasts in a Mouse/Human Chimeric Model. Rejuvenation Res. 2023, 26, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.-X.; Li, Z.-S.; Liu, Y.-B.; Pan, B.; Fu, X.; Xiao, R.; Yan, L. FOXO4-DRI induces keloid senescent fibroblast apoptosis by promoting nuclear exclusion of upregulated p53-serine 15 phosphorylation. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.H.; De, R.; Lee, K.T. Emerging strategies to fabricate polymeric nanocarriers for enhanced drug delivery across blood-brain barrier: An overview. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 320, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, S.; Kirsch, V.; Ruths, L.; Brenner, R.E.; Riegger, J. Senolytic therapy combining Dasatinib and Quercetin restores the chondrogenic phenotype of human osteoarthritic chondrocytes by the release of pro-anabolic mediators. Aging Cell 2024, 24, e14361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia-Vieni, A.; Marchant, V.; Tejedor-Santamaria, L.; García-Caballero, C.; Flores-Salguero, E.; Ruiz-Torres, M.P.; Rayego-Mateos, S.; Sanz, A.B.; Ortiz, A.; Ruiz-Ortega, M. Dasatinib and Quercetin Combination Increased Kidney Damage in Acute Folic Acid-Induced Experimental Nephropathy. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, C.; Yang, L. Cellular senescence in Alzheimer’s disease: From physiology to pathology. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riessland, M.; Orr, M.E. Translating the Biology of Aging into New Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease: Senolytics. J. Prev. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 10, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, V.; Krautter, F.; Klein, D.; Jendrossek, V.; Rudner, J. Bcl-2/Bcl-xL inhibitor ABT-263 overcomes hypoxia-driven radioresistence and improves radiotherapy. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, Y.; Makarcyzk, M.J.; Lin, H. Senolytic Peptide FOXO4-DRI Selectively Removes Senescent Cells from in vitro Expanded Human Chondrocytes. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 677576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, B.; Spreitzer, E.; Platero-Rochart, D.; Paar, M.; Zhou, Q.; Usluer, S.; de Keizer, P.L.J.; Burgering, B.M.T.; Sanchez-Murcia, P.A.; Madl, T. The disordered p53 transactivation domain is the target of FOXO4 and the senolytic compound FOXO4-DRI. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Wei, Z.; Feng, S. Senescence- and Immunity-Related Changes in the Central Nervous System: A Comprehensive Review. Aging Dis. 2025, 16, 2177–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Câmara, N.O.S.; Hoff, U.; Markmann, D.; Thurn-Valassina, D.; Nieminen-Kelhä, M.; Erlangga, Z.; Schmitz, J.; Bräsen, J.H.; Budde, K.; Melk, A.; et al. The mTOR inhibitor Rapamycin protects from premature cellular senescence early after experimental kidney transplantation. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.-J.; Zhang, S.-X.; Li, Y.; Xu, S.-Y. Rapamycin Responds to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Potential Translational Therapy. Clin. Interv. Aging 2023, 18, 1629–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, S.; Singh, R.; Singh, V.; Singh, H.; Kumari, P.; Chopra, H.; Sharma, R.; Nepovimova, E.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K.; et al. Metformin: Activation of 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase and its emerging potential beyond anti-hyperglycemic action. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1022739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-H.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Sun, Y.-Q.; Lv, R.-H.; Chen, M.; Li, M. Metformin use is associated with a reduced risk of cognitive impairment in adults with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 984559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerrero, A.; De Strooper, B.; Arancibia-Carcamo, I.L. Cellular senescence at the crossroads of inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2021, 44, 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, M.M.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Garbarino, V.; Daeihagh, A.S.; Gillispie, G.J.; Deep, G.; Craft, S.; Orr, M.E. A geroscience motivated approach to treat Alzheimer’s disease: Senolytics move to clinical trials. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2021, 200, 111589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farr, J.N.; Monroe, D.G.; Atkinson, E.J.; Froemming, M.N.; Ruan, M.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; Khosla, S. Characterization of Human Senescent Cell Biomarkers for Clinical Trials. Aging Cell 2025, 24, e14489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.A.; Faizan, M.I.; Kaur, G.; Shaikh, S.B.; Ul Islam, K.; Rahman, I. Heterogeneity of Cellular Senescence, Senotyping, and Targeting by Senolytics and Senomorphics in Lung Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, T.; Czerniel, J.; Dobrosielski, J.; Stawny, M. Flavonol Technology: From the Compounds’ Chemistry to Clinical Research. Molecules 2025, 30, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enderami, A.; Shariati, B.; Zarghami, M.; Aliasgharian, A.; Ghazaiean, M.; Darvishi-Khezri, H. Metformin and Cognitive Performance in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: An Umbrella Review. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2025, 45, e12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaeberlein, M. RTB101 and immune function in the elderly: Interpreting an unsuccessful clinical trial. Transl. Med. Aging 2020, 4, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, S.C.; Ferguson, E.L.; Choudhary, V.; Ranatunga, D.K.; Oni-Orisan, A.; Hayes-Larson, E.; Duarte Folle, A.; Mayeda, E.R.; Whitmer, R.A.; Gilsanz, P.; et al. Metformin Cessation and Dementia Incidence. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2339723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhoune, L.; Poggi, C.; Moreau, J.; Dubucquoi, S.; Hachulla, E.; Collet, A.; Launay, D. JAK inhibitors (JAKi): Mechanisms of action and perspectives in systemic and autoimmune diseases. Rev. Médecine Interne 2025, 46, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawky, A.M.; Almalki, F.A.; Abdalla, A.N.; Abdelazeem, A.H.; Gouda, A.M. A Comprehensive Overview of Globally Approved JAK Inhibitors. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaebi, F.; Sciortino, A.; Kayed, R. The Role of Glial Cell Senescence in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamatta, R.; Pai, V.; Jaiswal, C.; Singh, I.; Singh, A.K. Neuroinflammaging and the Immune Landscape: The Role of Autophagy and Senescence in Aging Brain. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, J.; Aggarwal, A.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Sahni, D.; Sharma, V.; Aggarwal, A. Fisetin and resveratrol exhibit senotherapeutic effects and suppress cellular senescence in osteoarthritic cartilage-derived chondrogenic progenitor cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 997, 177573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorigatti, A.O.; Riordan, R.; Yu, Z.; Ross, G.; Wang, R.; Reynolds-Lallement, N.; Magnusson, K.; Galvan, V.; Perez, V.I. Brain cellular senescence in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Geroscience 2022, 44, 1157–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandra Lopes, P.; Guil-Guerrero, J.L. Beyond Transgenic Mice: Emerging Models and Translational Strategies in Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzystyniak, A.; Wesierska, M.; Petrazzo, G.; Gadecka, A.; Dudkowska, M.; Bielak-Zmijewska, A.; Mosieniak, G.; Figiel, I.; Wlodarczyk, J.; Sikora, E. Combination of dasatinib and quercetin improves cognitive abilities in aged male Wistar rats, alleviates inflammation and changes hippocampal synaptic plasticity and histone H3 methylation profile. Aging 2022, 14, 572–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Guo, T.; Chen, X.; Zhou, X.; Sun, Y. Senolytic Treatment Attenuates Global Ischemic Brain Injury and Enhances Cognitive Recovery by Targeting Mitochondria. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 45, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, H.; Kodama, A. Dasatinib plus quercetin attenuates some frailty characteristics in SAMP10 mice. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, A.D.; Vemuri, R.; Blawas, M.; Long, M.; DeStephanis, D.; Williams, A.G.; Chen, H.; Justice, J.N.; Macauley, S.L.; Day, S.M.; et al. Long-term dasatinib plus quercetin effects on aging outcomes and inflammation in nonhuman primates: Implications for senolytic clinical trial design. Geroscience 2023, 45, 2785–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, Z.D.; Strong, R. Rapamycin, the only drug that has been consistently demonstrated to increase mammalian longevity. An update. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 176, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szőke, K.; Bódi, B.; Hendrik, Z.; Czompa, A.; Gyöngyösi, A.; Haines, D.D.; Papp, Z.; Tósaki, Á.; Lekli, I. Rapamycin treatment increases survival, autophagy biomarkers and expression of the anti-aging klotho protein in elderly mice. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2023, 11, e01091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, T.; Begum, F.; Kumar, G.; Shenoy, S.; Kumar, N.; Shenoy, R.R. Exploring the protective role of metformin and dehydrozingerone in sodium fluoride-induced neurotoxicity: Evidence from prenatal rat models. 3 Biotech 2025, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehraban, R.A.M.; Babaei, P.; Rohampour, K.; Jafari, A.; Golipoor, Z. Metformin improves memory via AMPK/mTOR-dependent route in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2024, 27, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, C.L.; Iloputaife, I.; Baldyga, K.; Norling, A.M.; Boulougoura, A.; Vichos, T.; Tchkonia, T.; Deisinger, A.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Kirkland, J.L.; et al. A pilot study of senolytics to improve cognition and mobility in older adults at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. eBioMedicine 2025, 113, 105612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, M.M.; Garbarino, V.R.; Kautz, T.F.; Palavicini, J.P.; Lopez-Cruzan, M.; Dehkordi, S.K.; Mathews, J.J.; Zare, H.; Xu, P.; Zhang, B.; et al. Senolytic therapy in mild Alzheimer’s disease: A phase 1 feasibility trial. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2481–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Su, W.; Zhuo, Y. New Insights into the Role of Cellular Senescence and Its Therapeutic Implications in Ocular Diseases. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepacki, H.; Kowalczuk, K.; Łepkowska, N.; Hermanowicz, J.M. Molecular Regulation of SASP in Cellular Senescence: Therapeutic Implications and Translational Challenges. Cells 2025, 14, 942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Zhou, H. Persistent accumulation of therapy-induced senescent cells: An obstacle to long-term cancer treatment efficacy. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2025, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rino, F.; Rispoli, F.; Zuffi, M.; Matteucci, E.; Gavazzi, A.; Salvatici, M.; Sansico, D.F.; Pollaroli, G.; Drago, L. Assessment of Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias: A Center-Based Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanaprukskul, K.; Xia, X.J.; Hysa, M.; Jiang, M.; Hung, M.; Suslavich, S.F.; Sahingur, S.E. Dasatinib and Quercetin Limit Gingival Senescence, Inflammation, and Bone Loss. J. Dent. Res. 2025, 104, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, A.; Bean, L.; Budamagunta, V.; Kumar, A.; Foster, T.C. Failure of senolytic treatment to prevent cognitive decline in a female rodent model of aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1384554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, B.L.; Cadar, A.N.; Martin, D.E.; Panier, H.A.; Lorenzo, E.C.; Bartley, J.M.; Xu, M.; Haynes, L. Senolytic treatment with dasatinib and quercetin does not improve overall influenza responses in aged mice. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1212750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spray, L.; Richardson, G.; Booth, L.K.; Haendeler, J.; Altschmied, J.; Bromage, D.I.; Wallis, S.B.; Stellos, K.; Tual-Chalot, S.; Spyridopoulos, I. How to measure and model cardiovascular aging. Cardiovasc. Res. 2025, 121, 1489–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qoura, L.A.; Churov, A.V.; Maltseva, O.N.; Arbatskiy, M.S.; Tkacheva, O.N. The aging interactome: From cellular dysregulation to therapeutic frontiers in age-related diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Basis Dis. 2026, 1872, 168060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Jalouli, M.; Yadab, M.K.; Al-Zharani, M. Progress in Drug Delivery Systems Based on Nanoparticles for Improved Glioblastoma Therapy: Addressing Challenges and Investigating Opportunities. Cancers 2025, 17, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Qiao, X.; Fang, Y.; Guo, R.; Bai, P.; Liu, S.; Li, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wei, S.; Na, Z.; et al. Epigenetics-targeted drugs: Current paradigms and future challenges. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. From Bench to Bedside: Translating Cellular Rejuvenation Therapies into Clinical Applications. Cells 2024, 13, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Xie, Y.; Fan, R.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Dong, P. Exercise orchestrates systemic metabolic and neuroimmune homeostasis via the brain–muscle–liver axis to slow down aging and neurodegeneration: A narrative review. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Ibrahim, A.; Hamide, A.; Tran, T.; Candreva, E.; Baltaji, J. Exercise-Induced Neuroplasticity: Adaptive Mechanisms and Preventive Potential in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Physiologia 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Senotherapeutics for Brain Aging Management. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120204

Saliev T, Singh PB. Senotherapeutics for Brain Aging Management. Neurology International. 2025; 17(12):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120204

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaliev, Timur, and Prim B. Singh. 2025. "Senotherapeutics for Brain Aging Management" Neurology International 17, no. 12: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120204

APA StyleSaliev, T., & Singh, P. B. (2025). Senotherapeutics for Brain Aging Management. Neurology International, 17(12), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120204