Serum Aquaporin-4 Antibody Status and TGF-β in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Astrocyte Function and Correlation with Disease Activity and Severity

Abstract

1. Introduction

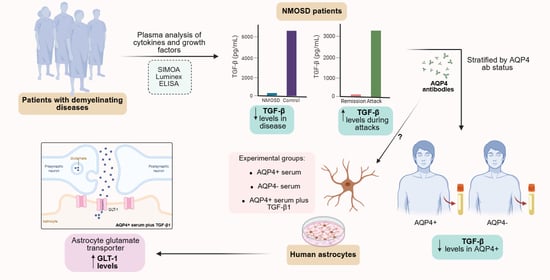

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Data Review

2.2. Sample Selection

2.3. Sample Collection

2.4. Interleukins and Growth Factors Measurement

2.5. Human Astrocyte Culture and Treatments

2.6. Immunocytochemistry and Densitometric Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

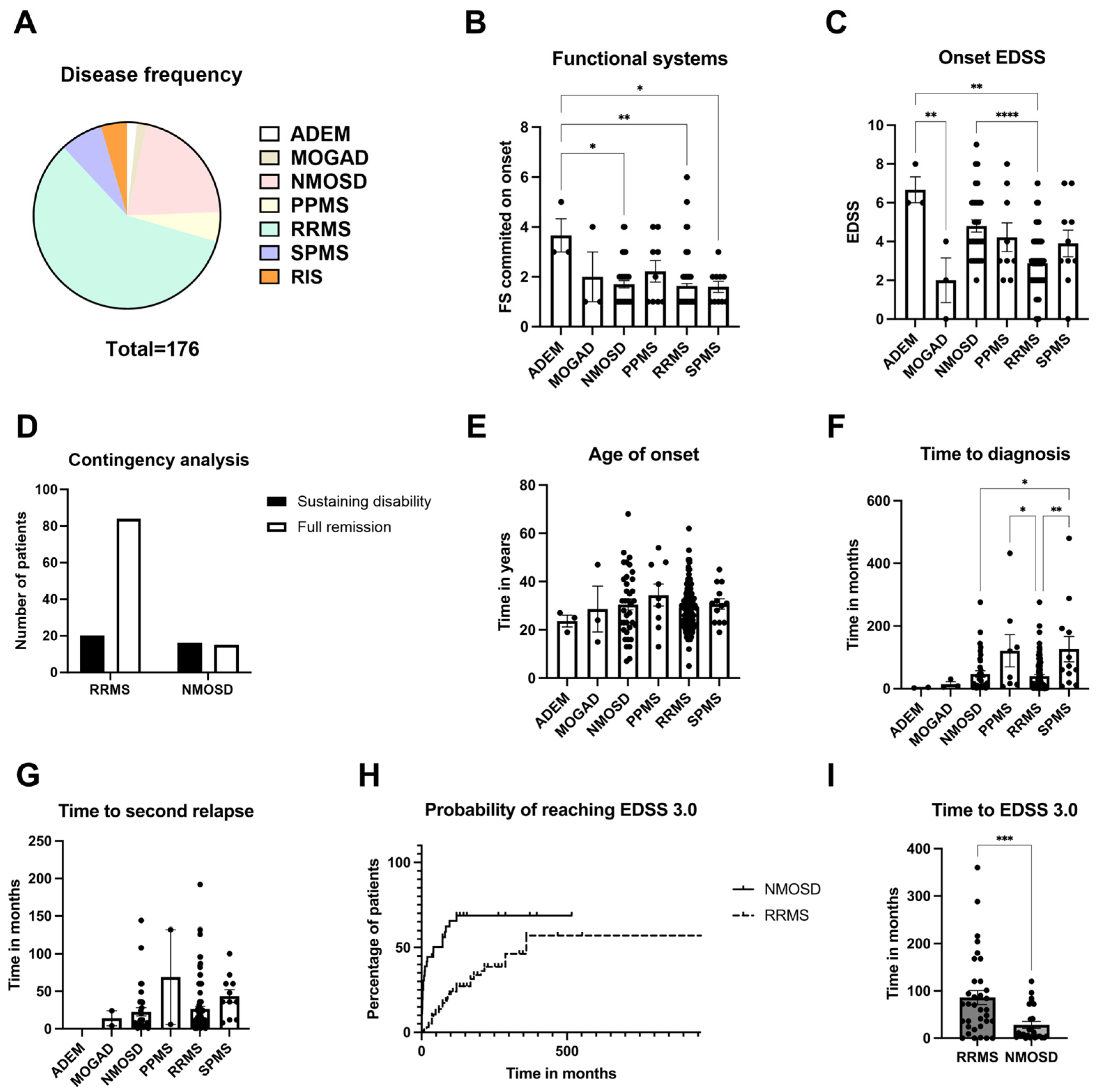

3.1. Onset Characteristics of Inflammatory Demyelinating Diseases at a Tertiary Hospital

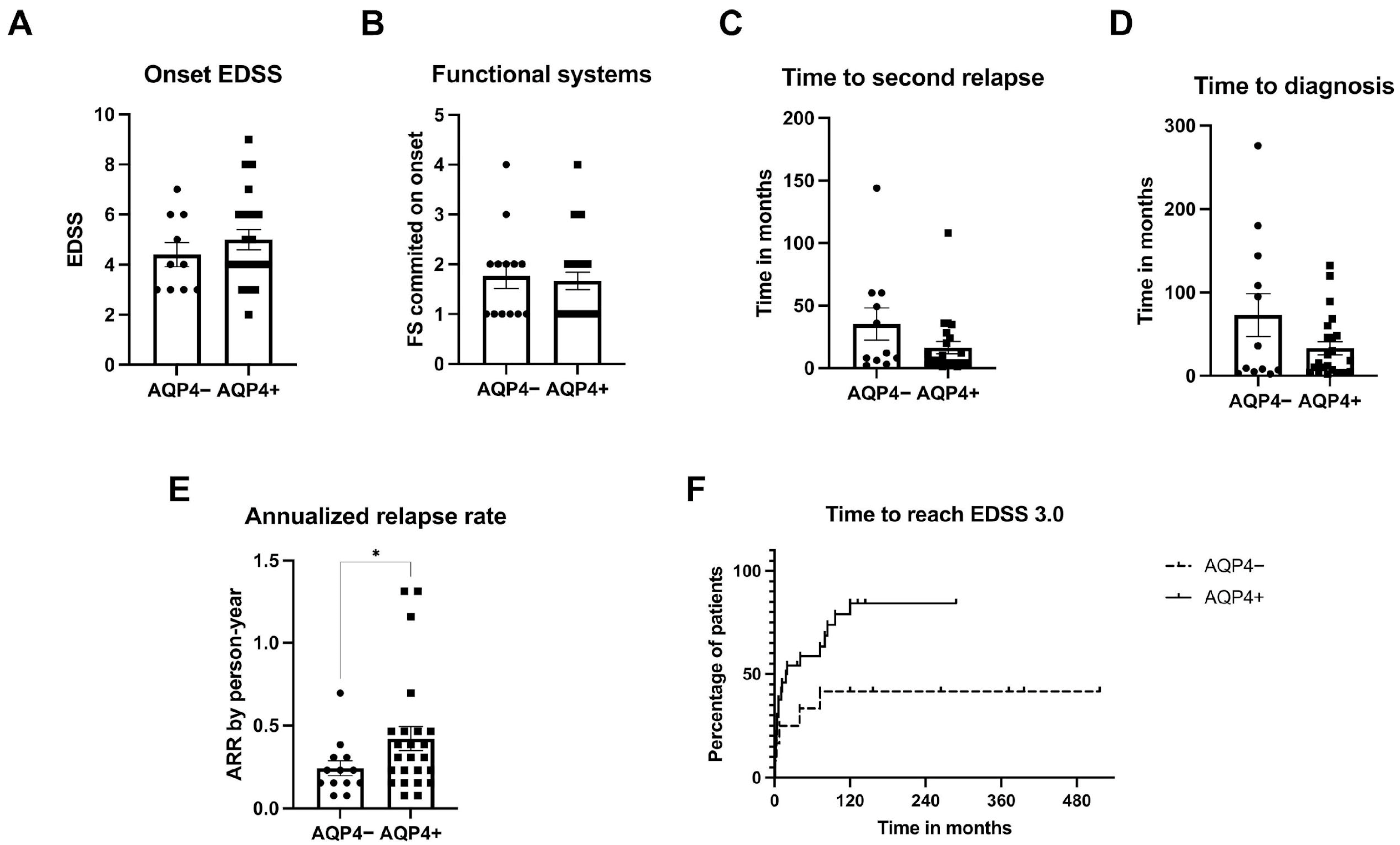

3.2. Characteristics of NMOSD Patients According to AQP4 ab Status

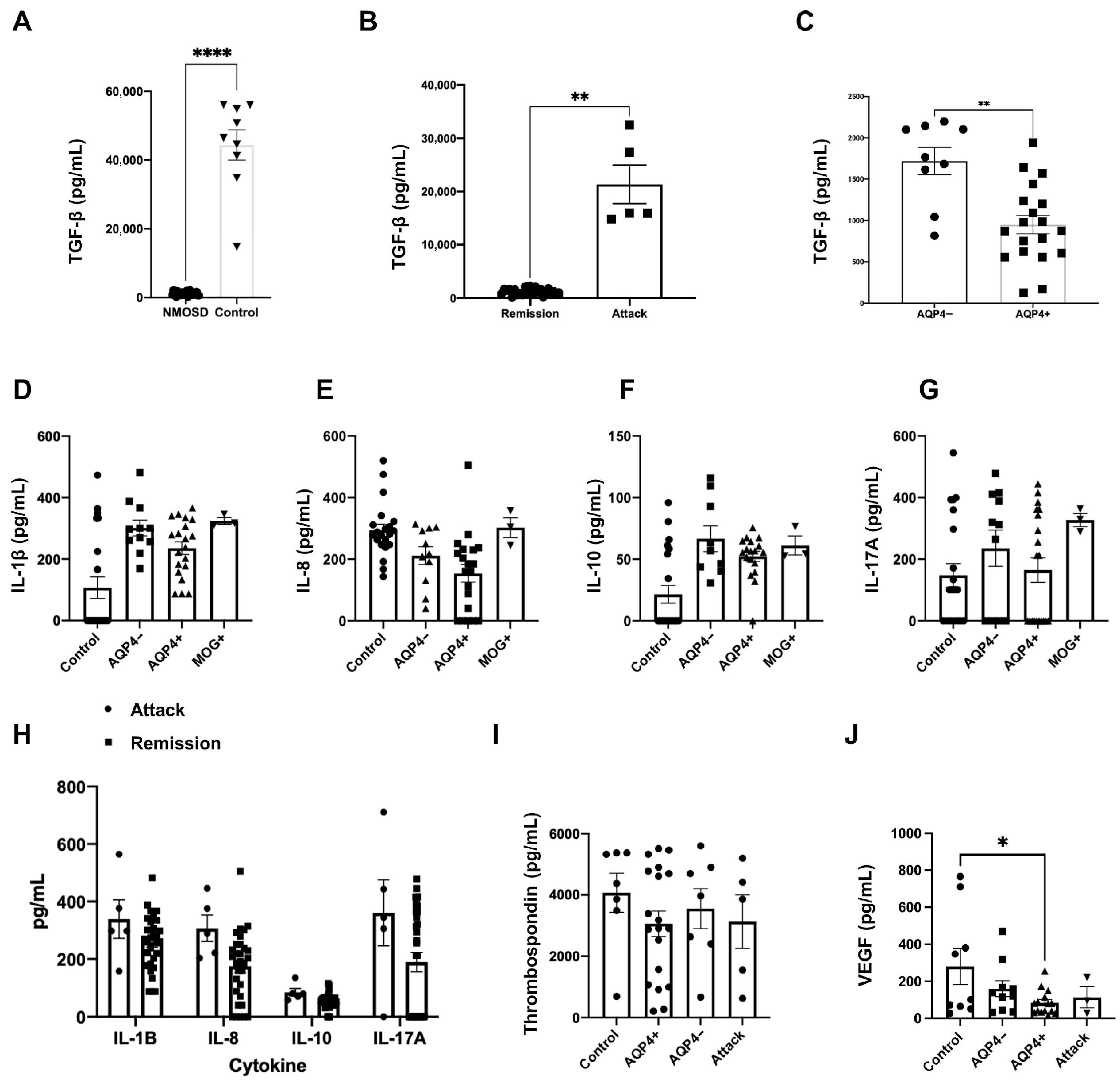

3.3. Plasmatic Concentrations of Interleukins and Growth Factors in NMOSD

3.4. TGF-β Plasmatic Concentrations Among Different Disease Groups

3.5. Expression of Inflammation and Glutamate Metabolism Markers on Cultured Human Astrocytes Treated with NMOSD Patient Serum

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cao, F.; He, Y.-S.; Wang, Y.; Zha, C.-K.; Lu, J.-M.; Tao, L.-M.; Jiang, Z.-X.; Pan, H.-F. Global burden and cross-country inequalities in autoimmune diseases from 1990 to 2019. Autoimmun. Rev. 2023, 22, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiardi, S.; Quadalti, C.; Mammana, A.; Dellavalle, S.; Zenesini, C.; Sambati, L.; Pantieri, R.; Polischi, B.; Romano, L.; Suffritti, M.; et al. Diagnostic value of plasma p-tau181, NfL, and GFAP in a clinical setting cohort of prevalent neurodegenerative dementias. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennon, V.A.; Kryzer, T.J.; Pittock, S.J.; Verkman, A.S.; Hinson, S.R. IgG marker of optic-spinal multiple sclerosis binds to the aquaporin-4 water channel. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 202, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Fryer, J.P.; Lennon, V.A.; Jenkins, S.M.; Quek, A.M.L.; Smith, C.Y.; McKeon, A.; Costanzi, C.; Iorio, R.; Weinshenker, B.G.; et al. Updated estimate of AQP4-IgG serostatus and disability outcome in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 2013, 81, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidsvaag, V.A.; Enger, R.; Hansson, H.-A.; Eide, P.K.; Nagelhus, E.A. Human and mouse cortical astrocytes differ in aquaporin-4 polarization toward microvessels. Glia 2017, 65, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho Costa, V.G.; Araújo, S.E.-S.; Alves-Leon, S.V.; Gomes, F.C.A. Central nervous system demyelinating diseases: Glial cells at the hub of pathology. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1135540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alisch, M.; Foersterling, F.; Zocholl, D.; Muinjonov, B.; Schindler, P.; Duchnow, A.; Otto, C.; Ruprecht, K.; Schmitz-Hübsch, T.; Jarius, S.; et al. Distinguishing Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders Subtypes: A Study on AQP4 and C3d Epitope Expression in Cytokine-Primed Human Astrocytes. Glia 2025, 73, 1090–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tradtrantip, L.; Asavapanumas, N.; Verkman, A.S. Emerging therapeutic targets for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2020, 24, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, H.; Song, Y.-S.; Sorenson, C.M.; Sheibani, N. Thrombospondin-1 in vascular development, vascular function, and vascular disease. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 155, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzke, J.F. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: An expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983, 33, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingerchuk, D.M.; Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Cabre, P.; Carroll, W.; Chitnis, T.; De Seze, J.; Fujihara, K.; Greenberg, B.; Jacob, A.; et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology 2015, 85, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban, X.; Lebrun-Frénay, C.; Oh, J.; Arrambide, G.; Moccia, M.; Pia Amato, M.; Amezcua, L.; Banwell, B.; Bar-Or, A.; Barkhof, F.; et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2024 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2025, 24, 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banwell, B.; Bennett, J.L.; Marignier, R.; Kim, H.J.; Brilot, F.; Flanagan, E.P.; Ramanathan, S.; Waters, P.; Tenembaum, S.; Graves, J.S.; et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, D.; Alper, G.; Van Haren, K.; Kornberg, A.J.; Lucchinetti, C.F.; Tenembaum, S.; Belman, A.L. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Updates on an inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology 2016, 87 (Suppl. S2), S38–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.P.; Almeida, J.C.; Tortelli, V.; Vargas Lopes, C.; Setti-Perdigão, P.; Stipursky, J.; Kahn, S.A.; Romão, L.F.; De Miranda, J.; Alves-Leon, S.V.; et al. Astrocyte-induced Synaptogenesis Is Mediated by Transforming Growth Factor β Signaling through Modulation of d-Serine Levels in Cerebral Cortex Neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 41432–41445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matias, I.; Diniz, L.P.; Damico, I.V.; Araujo, A.P.B.; da Silva Neves, L.; Vargas, G.; Leite, R.E.P.; Suemoto, C.K.; Nitrini, R.; Jacob-Filho, W.; et al. Loss of lamin-B1 and defective nuclear morphology are hallmarks of astrocyte senescence in vitro and in the aging human hippocampus. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noursadeghi, M.; Tsang, J.; Haustein, T.; Miller, R.F.; Chain, B.M.; Katz, D.R. Quantitative imaging assay for NF-κB nuclear translocation in primary human macrophages. J. Immunol. Methods 2008, 329, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.B.D.; Souza, D.G.; Souza, D.O.; Machado, D.C.; Sato, D.K. Role of Glutamatergic Excitotoxicity in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papais-Alvarenga, R.M.; Vasconcelos, C.C.; Alves-Leon, S.V.; Batista, E.; Santos, C.M.; Camargo, S.M.; Godoy, M.; Lacativa, M.C.; Lorenti, M.; Damasceno, B.; et al. The impact of diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica in patients with MS: A 10-year follow-up of the South Atlantic Project. Mult. Scler. J. 2014, 20, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümpfel, T.; Giglhuber, K.; Aktas, O.; Ayzenberg, I.; Bellmann-Strobl, J.; Häußler, V.; Havla, J.; Hellwig, K.; Hümmert, M.W.; Jarius, S.; et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD)—Revised recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Part II: Attack therapy and long-term management. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 141–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidian, A.; AbdNikfarjam, B.; Maleki, P. Concomitant Expression of IL-6 and TGF-β Cytokines and their Receptors in Peripheral Blood of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: The Effects of INFβ Drugs. Iran. J. Immunol. 2022, 19, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharami, S.; Nourazarian, A.; Nikanfar, M.; Laghousi, D.; Shademan, B.; Joodi Khanghah, O.; Khaki-Khatibi, F. Investigation of serum levels of orexin-A, transforming growth factor β, and leptin in patients with multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Chang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Du, L.; Zhou, H.; Xu, W.; Ma, Y.; Yin, L.; Zhang, X. Cytokines and Tissue Damage Biomarkers in First-Onset Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders: Significance of Interleukin-6. Neuroimmunomodulation 2018, 25, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Sun, M.; Gao, J.; Xie, A. TGF-β in Mice Ameliorates Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in Regulating NK Cell Activity. Cell Transplant. 2019, 28, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espírito-Santo, S.; Coutinho, V.G.; Dezonne, R.S.; Stipursky, J.; Dos Santos-Rodrigues, A.; Batista, C.; Paes-de-Carvalho, R.; Fuss, B.; Gomes, F.C.A. Astrocytes as a target for Nogo-A and implications for synapse formation in vitro and in a model of acute demyelination. Glia 2021, 69, 1429–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, I.; Diniz, L.P.; Buosi, A.; Neves, G.; Stipursky, J.; Gomes, F.C.A. Flavonoid Hesperidin Induces Synapse Formation and Improves Memory Performance through the Astrocytic TGF-β1. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.P.; Matias, I.C.P.; Garcia, M.N.; Gomes, F.C.A. Astrocytic control of neural circuit formation: Highlights on TGF-beta signaling. Neurochem. Int. 2014, 78, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilzadeh, A.; Mohammadi, V.; Elahi, R. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) pathway in the immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS); molecular approaches. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6121–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.P.; Tortelli, V.; Matias, I.; Morgado, J.; Bérgamo Araujo, A.P.; Melo, H.M.; Seixas da Silva, G.S.; Alves-Leon, S.V.; de Souza, J.M.; Ferreira, S.T.; et al. Astrocyte Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 Protects Synapses against Aβ Oligomers in Alzheimer’s Disease Model. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2017, 37, 6797–6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.P.; Matias, I.; Siqueira, M.; Stipursky, J.; Gomes, F.C.A. Astrocytes and the TGF-β1 Pathway in the Healthy and Diseased Brain: A Double-Edged Sword. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 4653–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaishi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Nakashima, I.; Abe, M.; Ishii, T.; Aoki, M.; Fujihara, K. Repeated follow-up of AQP4-IgG titer by cell-based assay in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD). J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 410, 116671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Shi, M.; Liu, C.; Zhu, J. Discrepancy in clinical and laboratory profiles of NMOSD patients between AQP4 antibody positive and negative: Can NMOSD be diagnosed without AQP4 antibody? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2023, 213, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, S.R.; Clift, I.C.; Luo, N.; Kryzer, T.J.; Lennon, V.A. Autoantibody-induced internalization of CNS AQP4 water channel and EAAT2 glutamate transporter requires astrocytic Fc receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5491–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikura, T.; Kinoshita, M.; Shimizu, M.; Yasumizu, Y.; Motooka, D.; Okuzaki, D.; Yamashita, K.; Murata, H.; Beppu, S.; Koda, T.; et al. Anti-AQP4 autoantibodies promote ATP release from astrocytes and induce mechanical pain in rats. J. Neuroinflamm. 2021, 18, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhou, S.; Xu, Z.; Hu, G.; Su, C. Aquaporin-4 deficiency reduces TGF-β1 in mouse midbrains and exacerbates pathology in experimental Parkinson’s disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2568–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeglsperger, T.; Li, S.; Brenneis, C.; Saulnier, J.L.; Mayo, L.; Carrier, Y.; Selkoe, D.J.; Weiner, H.L. Impaired glutamate recycling and GluN2B-mediated neuronal calcium overload in mice lacking TGF-β1 in the CNS. Glia 2013, 61, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J. TGF-β as a Key Modulator of Astrocyte Reactivity: Disease Relevance and Therapeutic Implications. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, L.P.; Araujo, A.P.B.; Matias, I.; Garcia, M.N.; Barros-Aragão, F.G.Q.; De Melo Reis, R.A.; Foguel, D.; Braga, C.; Figueiredo, C.P.; Romão, L.; et al. Astrocyte glutamate transporters are increased in an early sporadic model of synucleinopathy. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 138, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ADEM | MOGAD | NMOSD | PPMS | RRMS | SPMS | RIS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 3 (1.70%) | 3 (1.70%) | 37 (21.02%) | 9 (5.11%) | 103 (58.52%) | 13 (7.39%) | 8 (4.54%) |

| Gender (% of total) | F: 66.67% M: 33.33% | F: 33.33% M: 66.67% | F: 86.49% M: 13.51% | F: 33.33% M: 66.67% | F: 71.85% M: 28.15% | F: 76.92% M: 23.08% | F: 62.50% M: 37.50% |

| Age (Years) | 27.33 ± 4.33 | 35.00 ± 9.61 | 43.49 ± 2.44 | 52.78 ± 4.88 | 42.25 ± 1.06 | 55.15 ± 3.08 | 44.88 ± 7.18 |

| Scholarity (% of total) | PS: 0.00% MS: 0.00% HS: 100.00% HE: 0.00% | PS: 0.00% MS: 33.33% HS: 66.67% HE: 0.00% | PS: 11.11% MS: 33.33% HS: 44.44% HE: 11.11% | PS: 0.00% MS: 50.00% HS: 33.33% HE: 16.67% | PS: 5.43% MS: 9.78% HS: 43.48% HE: 41.30% | PS: 11.11% MS: 11.11% HS: 55.55% HE: 22.22% | PS: 12.50% MS: 25.00% HS: 37.50% HE: 25.00% |

| Race (% of total) | B: 0.00% MR: 33.33% W: 33.33% NI: 33.33% | B: 0.00% MR: 0.00% W: 100.00% NI: 0.00% | B: 16.22% MR: 27.03% W: 45.95% NI: 10.81% | B: 22.22% MR: 33.33% W: 44.44% NI: 0.00% | B: 1.00% MR: 23.30% W: 64.08% NI: 11.65% | B: 0.00% MR: 23.08% W: 61.54% NI: 15.38% | B: 0.00% MR: 0.00% W: 75.00% NI: 25.00% |

| Follow-up time (Years) | 3.67 ± 2.19 | 6.33 ± 1.20 | 12.95 ± 1.79 | 18.33 ± 4.12 | 13.31 ± 0.83 | 24.38 ± 3.35 | 8.86 ± 3.14 |

| ARR (Person-years) | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.24 |

| DMD use (% of total) | 0.00% | 100.00% | 89.18% | 55.55% | 97.11% | 76.93% | 25.00% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coutinho-Costa, V.G.; Matias, I.; Fernandes, R.A.; Siqueira, M.; Duarte, L.A.; Fernandes, B.M.; de Souza, J.M.; Alves-Leon, S.V.; Gomes, F.C.A. Serum Aquaporin-4 Antibody Status and TGF-β in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Astrocyte Function and Correlation with Disease Activity and Severity. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120200

Coutinho-Costa VG, Matias I, Fernandes RA, Siqueira M, Duarte LA, Fernandes BM, de Souza JM, Alves-Leon SV, Gomes FCA. Serum Aquaporin-4 Antibody Status and TGF-β in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Astrocyte Function and Correlation with Disease Activity and Severity. Neurology International. 2025; 17(12):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120200

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoutinho-Costa, Vinicius Gabriel, Isadora Matias, Renan Amphilophio Fernandes, Michele Siqueira, Larissa Araujo Duarte, Beatriz Martins Fernandes, Jorge Marcondes de Souza, Soniza Vieira Alves-Leon, and Flávia Carvalho Alcantara Gomes. 2025. "Serum Aquaporin-4 Antibody Status and TGF-β in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Astrocyte Function and Correlation with Disease Activity and Severity" Neurology International 17, no. 12: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120200

APA StyleCoutinho-Costa, V. G., Matias, I., Fernandes, R. A., Siqueira, M., Duarte, L. A., Fernandes, B. M., de Souza, J. M., Alves-Leon, S. V., & Gomes, F. C. A. (2025). Serum Aquaporin-4 Antibody Status and TGF-β in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder: Impact on Astrocyte Function and Correlation with Disease Activity and Severity. Neurology International, 17(12), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120200