Predicting Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Burden Meets Emotional Balance in Early Disease

Abstract

1. Background

2. Methods

2.1. Study Type

2.2. Population, Sample, and Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Justification and Sample Size Calculation

2.4. Variables

2.4.1. Independent Variables

- Socio-epidemiological factors: sex, age, ethnicity, education level, marital status, employment status, and annual income.

- Clinical factors: presence of family history, autoimmune diseases, previous mononucleosis, pregnancy planning, tobacco and alcohol consumption, ongoing treatment, and initial symptoms.

2.4.2. Dependent Variables

- Quality of Life: physical health, role limitations related to physical or psychological problems, pain, mood, energy, health perception, social functioning, cognitive functioning, health-related concerns, and overall perception of QoL.

2.5. Instrument

2.6. Data Collection

Handling of Missing Data

2.7. Data Confidentiality and Ethical Considerations

2.8. Data Analysis

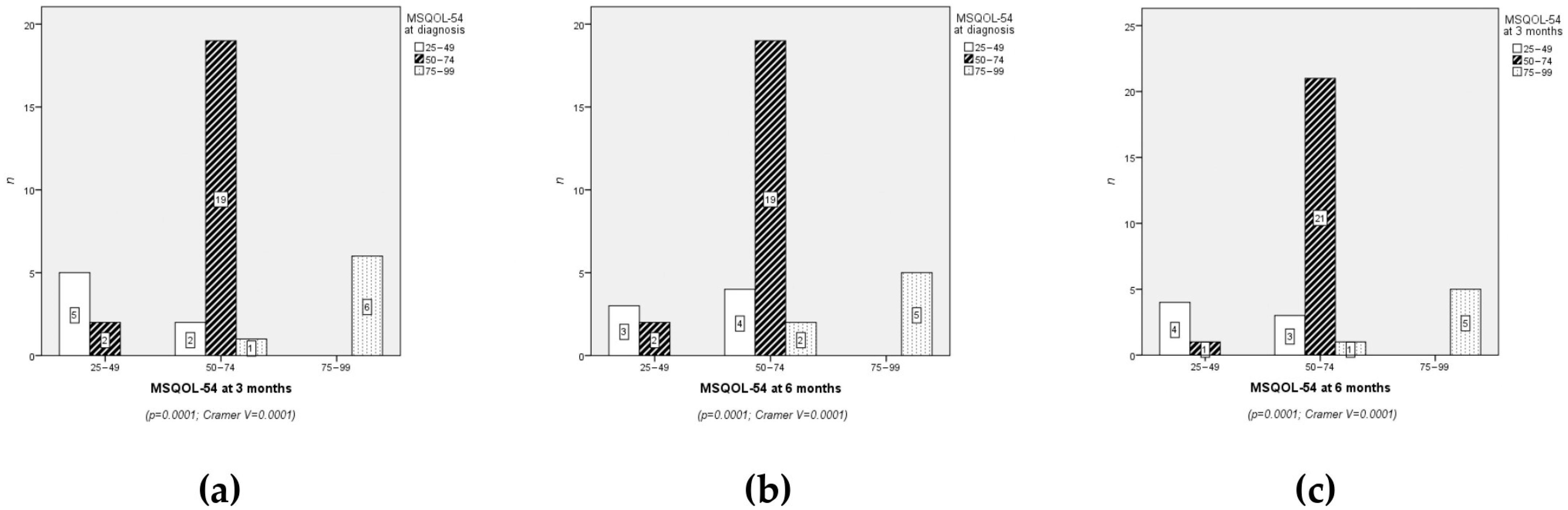

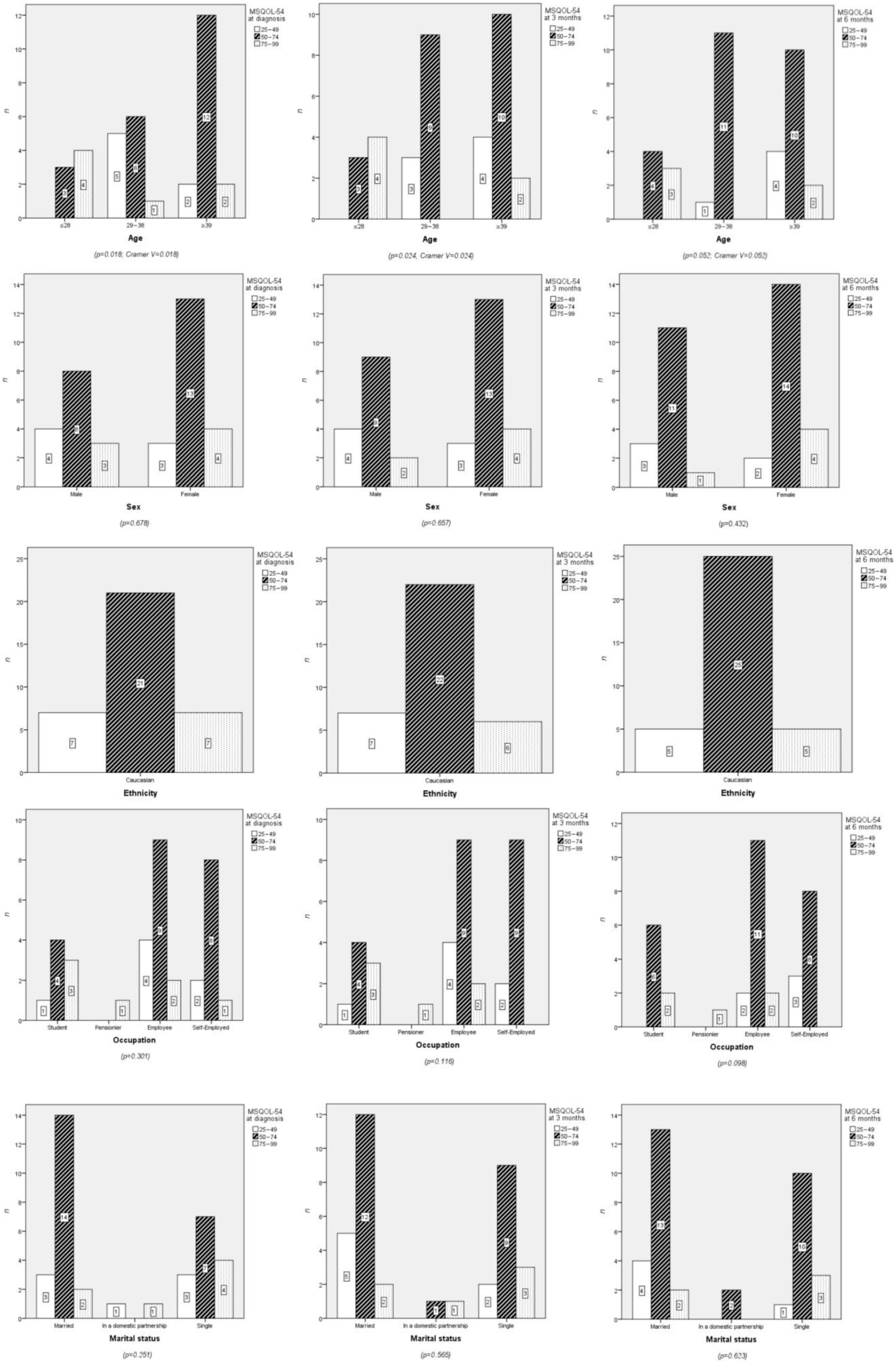

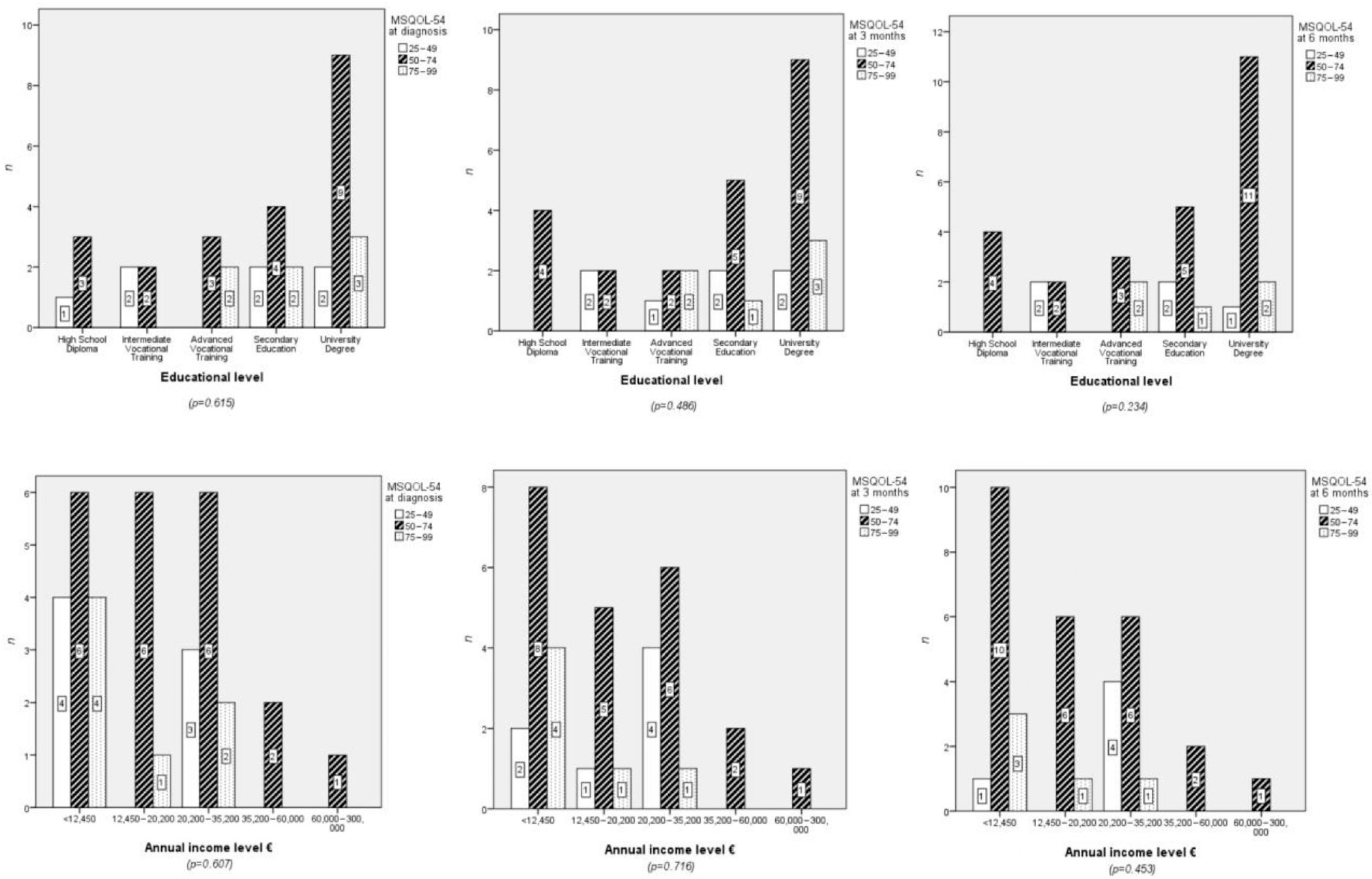

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.1.1. Age

3.1.2. Sex

3.2. Clinical Characteristics

3.2.1. Family History and Previous Diseases

3.2.2. Lifestyle Habits and Treatment

3.3. Clinical Results: Quality of Life

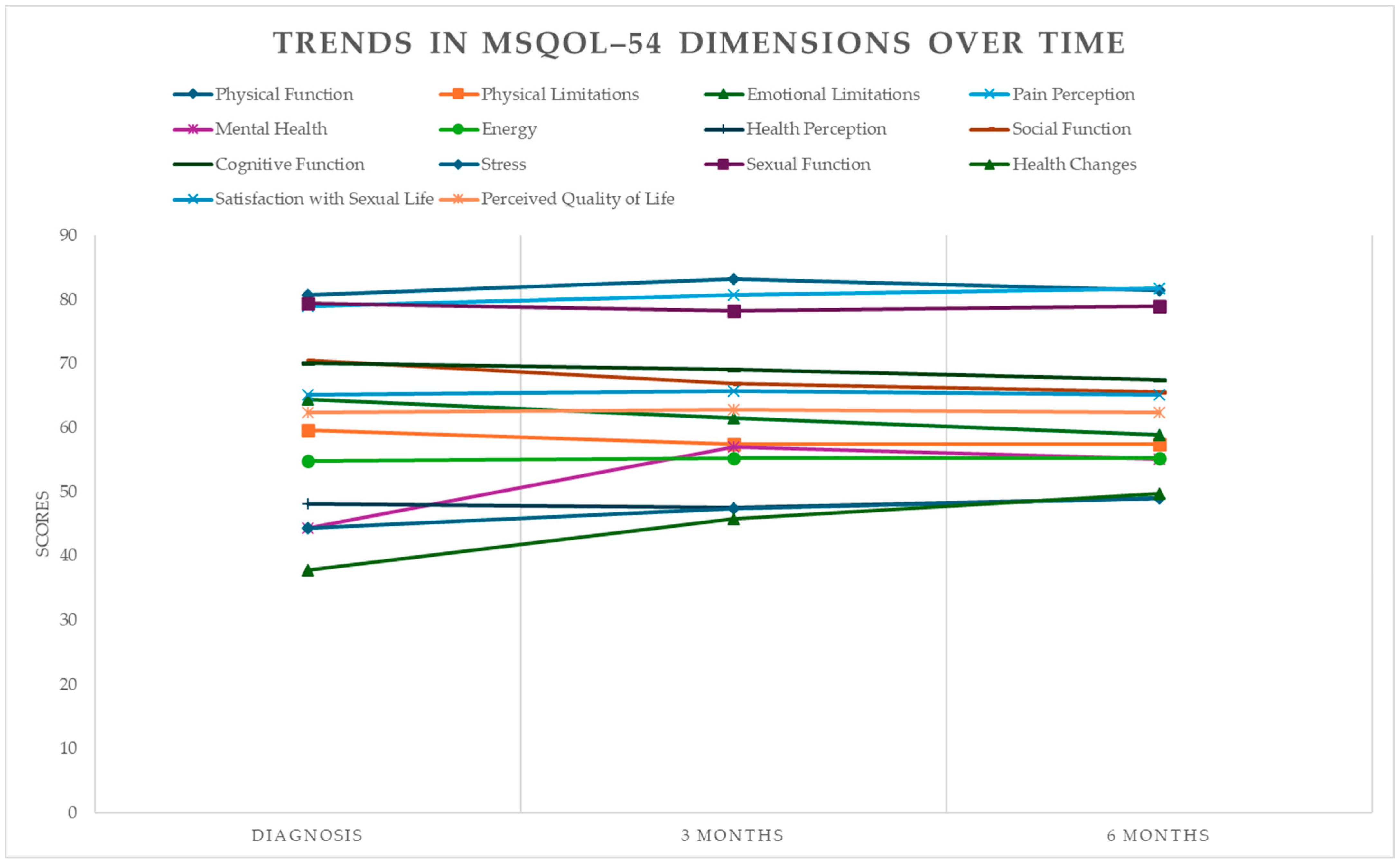

3.3.1. Physical Function

3.3.2. Physical Limitations

3.3.3. Emotional and Mental Health Limitations

3.3.4. Pain Perception

3.3.5. Mental Health

3.3.6. Energy

3.3.7. Health Perception

3.3.8. Social Function

3.3.9. Cognitive Function

3.3.10. Stress

3.3.11. Sexual Function

3.3.12. Health Changes Dimension

3.3.13. Sexual Satisfaction

3.3.14. Perceived Quality of Life

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationships Between Sociodemographic Variables and Quality of Life

4.2. Impact of Clinical Characteristics

4.3. Lifestyle Habits and Quality of Life

4.4. Evolution of Quality of Life

4.5. Clinical Implications and Future Research Directions

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Margoni, M.; Preziosa, P.; Rocca, M.A.; Filippi, M. Depressive symptoms, anxiety and cognitive impairment: Emerging evidence in multiple sclerosis. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pouyanfard, S.; Mohammadpour, M.; Parvizi Fard, A.A.; Sadeghi, K. Effectiveness of mindfulness–integrated cognitive behavior therapy on anxiety, depression and hope in multiple sclerosis patients: A randomized clinical trial. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2020, 42, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenger, A.; Calabrese, P. Comparing underlying mechanisms of depression in multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2021, 20, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoor, D.D.; Ahmed, D.O.; Al–Bajalan, S.J. Demographic, Clinical, and Molecular Determinants of Quality of Life and Oxidative Stress in Multiple Sclerosis: A Cross–Sectional Study from Sulaymaniyah, Iraq. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 75, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Péloquin, S.; Schmierer, K.; Leist, T.P.; Oh, J.; Murray, S.; Lazure, P. Challenges in multiple sclerosis care: Results from an international mixed–methods study. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 50, 102854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safiri, S.; Ghaffari Jolfayi, A.; Mousavi, S.E.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Sullman, M.J.; Kolahi, A.A. Global burden of multiple sclerosis and its attributable risk factors, 1990–2019. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1448377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B.E.; Lakin, L.; Binns, C.C.; Currie, K.M.; Rensel, M.R. Patient and provider insights into the impact of multiple sclerosis on mental health: A narrative review. Neur Ther. 2021, 10, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Liao, R.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Huo, S.; Qin, L.; Xiong, Y.; He, T.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, T. Mesenchymal stem cells in treating human diseases: Molecular mechanisms and clinical studies. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanese, A.M.; Bartz–Overman, C.; Parikh, T.; Thielke, S.M. Associations between activities of daily living independence and mental health status among medicare managed care patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2020, 68, 1301–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maresova, P.; Krejcar, O.; Maskuriy, R.; Abu Bakar, N.A.; Selamat, A.; Truhlarova, Z.; Horak, J.; Joukl, M.; Vítkova, L. Challenges and opportunity in mobility among older adults–key determinant identification. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, F.; Khoshravesh, S.; Ayubi, E.; Bashirian, S.; Barati, M. Psychosocial determinants of functional independence among older adults: A systematic review and meta–analysis. Health Promot. Perspect. 2024, 14, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Strober, L.B. Anxiety and depression in Multiple Sclerosis (MS): Antecedents, consequences, and differential impact on well–being and quality of life. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2020, 44, 102261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, G.; Mhizha-Murira, J.R.; Griffiths, H.; Bale, C.; Drummond, A.; Fitzsimmons, D.; Potter, K.-J.; Evangelou, N.; das Nair, R. Experiences of receiving a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: A meta–synthesis of qualitative studies. Disabil. Rehabil. 2023, 45, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.R.; Nair, R.D. The psychological impact of the unpredictability of multiple sclerosis: A qualitative literature meta–synthesis. Br. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2013, 9, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.S.; Casado, S.E.; Payero, M.Á.; Pueyo, Á.E.E.; Bernabé, Á.G.A.; Zamora, N.P.; Ruiz, P.D.; González, A.M.L. Tratamientos modificadores de la enfermedad en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple en España. Farm. Hosp. 2023, 47, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kołtuniuk, A.; Pawlak, B.; Krówczyńska, D.; Chojdak–Łukasiewicz, J. The quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis—Association with depressive symptoms and physical disability: A prospective and observational study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1068421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizaguirre, M.M.B.; Yastremiz, C.; Ciufia, N.; Roman, M.S.; Alonso, R.; Silva, B.A.; Garcea, O.; Cáceres, F.; Vanotti, S. Relevance and impact of social support on quality of life for persons with multiple sclerosis. Int. J. MS Care 2023, 25, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinsky–Ortiz, E.M.; Strober, L.B. Keeping it together: The role of social integration on health and psychological well-being among individuals with multiple sclerosis. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e4074–e4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acoba, E.F. Social support and mental health: The mediating role of perceived stress. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1330720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez Barbosa, E.A.; Guancha Aza, L.J.; Ávila Gelvez, J.A.; Gómez Alfonzo, A.E. Calidad de vida en pacientes con esclerosis múltiple. RECIAMUC 2021, 5, 4–12. [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca, L.G.; Izquierdo–Sanchez, L.; Hashizume, P.H.; Carlino, Y.; Baca, E.L.; Zambrano, C.; Sepúlveda, S.A.; Bolomo, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Riaño, I.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma in Latin America: A multicentre observational study alerts on ethnic disparities in tumour presentation and outcomes. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2024, 40, 100952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Warren, J.L.; Harries, A.D.; Croda, J.; A Espinal, M.; Olarte, R.A.L.; Avedillo, P.; Lienhardt, C.; Bhatia, V.; Liu, Q.; et al. Global, regional, and national estimates of tuberculosis incidence and case detection among incarcerated individuals from 2000 to 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet Public Health 2023, 8, e511–e519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.A.; Brasil, T.P.; Silva, C.S.; Frota, C.C.; Sardinha, D.M.; Figueira, L.R.T.; Neves, K.A.S.; dos Santos, E.C.; Lima, K.V.B.; Ghisi, N.d.C.; et al. Comparative analysis of the leprosy detection rate regarding its clinical spectrum through PCR using the 16S rRNA gene: A scientometrics and meta–analysis. Front. Microbiol 2024, 15, 1497319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García López, F.J.; García–Merino, A.; Alcalde–Cabero, E.; de Pedro–Cuesta, J. Incidencia y prevalencia de la esclerosis múltiple en España: Una revisión sistemática. Neurología 2022, 39, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meca-Lallana, J.; Yélamos, S.M.; Eichau, S.; Llaneza, M.; Martínez, J.M.; Martínez, J.P.; Lallana, V.M.; Torres, A.A.; Torres, E.M.; Río, J.; et al. Documento de consenso de la Sociedad Española de Neurología sobre el tratamiento de la esclerosis múltiple y manejo holístico del paciente 2023. Neurología 2024, 39, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waubant, E.; Lucas, R.; Mowry, E.; Graves, J.; Olsson, T.; Alfredsson, L.; Langer-Gould, A. Environmental and genetic risk factors for MS: An integrated review. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019, 6, 1905–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombash, S.E.; Lee, P.W.; Sawdai, E.; Lovett–Racke, A.E. Vitamin D as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis: Immunoregulatory or neuroprotective? Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 796933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazou, V.; Schluep, M.; Du Pasquier, R. Environmental factors in multiple sclerosis. La. Presse Médicale 2015, 44, e113–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitturi, B.K.; Cellerino, M.; Boccia, D.; Leray, E.; Correale, J.; Dobson, R.; van der Mei, I.; Fujihara, K.; Inglese, M. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis: A comprehensive systematic review and meta–analysis. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moases Ghaffary, E.; Yazdan Panah, M.; Vaheb, S.; Ghoshouni, H.; Shaygannejad, A.; Mazloomi, M.; Shaygannejad, V.; Mirmosayyeb, O. Clinical and psychological factors associated with fear of relapse in people with multiple sclerosis: A cross–sectional study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2025, 135, 111210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittengl, J.R.; Clark, L.A.; Thase, M.E.; Jarrett, R.B. Stable remission and recovery after acute–phase cognitive therapy for recurrent major depressive disorder. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014, 82, 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.J.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, J.J.; Yu, J.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Won, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, S.H.; Kim, E.; et al. Defining Treatment Response, Remission, Relapse, and Recovery in First–Episode Psychosis: A Survey among Korean Experts. Psychiatry Investig. 2020, 17, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berk, M.S.; Gallop, R.; Asarnow, J.R.; Adrian, M.C.; Hughes, J.L.; McCauley, E. Remission, Recovery, Relapse, and Recurrence Rates for Suicide Attempts and Nonsuicidal Self–Injury for Suicidal Youth Treated with Dialectical Behavior Therapy or Supportive Therapy. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Negro, I.; Pez, S.; Gigli, G.L.; Valente, M. Disease Activity and Progression in Multiple Sclerosis: New Evidences and Future Perspectives. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, G.; Yang, J.; Pang, L.; Li, X. Pathological mechanisms and treatment progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2025, 30, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Nie, K.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S. Insights into the historical trajectory and research trends of immune checkpoint blockade in colorectal cancer: Visualization and bibliometric analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1478773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, M.A.; Mora, S. Evaluación de la calidad de vida mediante cuestionario PRIMUS en población española de pacientes con esclerosis múltiple. Neurología 2013, 28, 340–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, T.W.; Cha, Y.; Wolf, S.; Khan, M. Household economic instability: Constructs, measurement, and implications. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeineddine, M.; Ismail, G.; Issa, M.; El–Hajj, T.; Tfaily, H.; Dassouki, M.; Assaf, E.; Abboud, H.; Salameh, P.; Al–Hajje, A.; et al. Quality of life and access to treatment for patients with multiple sclerosis during economic crisis: The Lebanese experience. Qual. Life Res. 2025, 34, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.A.; Hiltner, S. Unsettled Employment, Reshuffled Priorities? Career Prioritization among College–Educated Workers Facing Employment Instability during COVID–19. Socius 2022, 8, 23780231211068660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Fung, V. Health Care Affordability Problems by Income Level and Subsidy Eligibility in Medicare. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e2532862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.M. Barriers to health equity in the United States of America: Can they be overcome? Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braley, T.J.; Chervin, R.D. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Mechanisms, evaluation, and treatment. Sleep 2010, 33, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, G. Multiple sclerosis related fatigue. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva Ramirez, A.; Keenan, A.; Kalau, O.; Worthington, E.; Cohen, L.; Singh, S. Prevalence and burden of multiple sclerosis–related fatigue: A systematic literature review. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Amatya, B.; Galea, M. Management of fatigue in persons with multiple sclerosis. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLuca, J. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis: Can we measure it and can we treat it? J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 6388–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Denend, T.; Gecht–Silver, M.; Kish, J.; Plow, M.; Preissner, K. Appreciating the experience of multiple sclerosis fatigue. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2023, 86, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourihan, S.J. Managing fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis. Nurs. Stand. 2015, 29, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicras–Mainar, A.; Ruíz–Beato, E.; Navarro–Artieda, R.; Maurino, J. Impact on healthcare resource utilization of multiple sclerosis in Spain. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Espejo, M.D.; Limiñana-Gras, R.M.; Patró-Hernández, R.M.; Lallana, J.E.M.; Robles, E.A.; Rebollo, M.d.C.M. Evaluación de la calidad de vida en Esclerosis Múltiple a través del MSQOL–54 y su relación con la salud de la persona. Enferm. Glob. 2021, 20, 217–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, O.; Fernández, V.; Baumstarck-Barrau, K.; Muñoz, L.; Alvarez, M.d.M.G.; Arrabal, J.C.; León, A.; Alonso, A.; López-Madrona, J.C.; Bustamante, R. Validation of the spanish version of the multiple sclerosis international quality of life (musiqol) questionnaire. BMC Neurol. 2011, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil–González, I.; Martín–Rodríguez, A.; Conrad, R.; Pérez–San–Gregorio, M.Á. Quality of life in adults with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.A.; Rog, D.; Sharrack, B.; Chhetri, S.K.; Kalra, S.; Harrower, T.; Webster, G.; Thorpe, J.; Nicholas, R.; Ford, H.L.; et al. Clinical and socio–demographic characteristics of people with multiple sclerosis at the time of diagnosis: Influences on outcome trajectories. J. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 470, 123409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasiuk, J.; Kapica-Topczewska, K.; Czarnowska, A.; Chorąży, M.; Snarska, K.K.; Kochanowicz, J.; Bartosik-Psujek, H.; Rościszewska-Żukowska, I.; Czarnota, J.; Kalinowska, A.; et al. Improving Quality of Life in Polish patients with multiple sclerosis: A multicentre analysis. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2025, 59, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo–Zuñiga, M.F.; Roman–Guzman, R.M.; Rodríguez–Leyva, I. Cognitive Performance and Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: A BICAMS– and PROs–Based Study in a Mexican Public Hospital. NeuroSci 2025, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Qiao, X.; Jia, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, P.; Hu, M. Health–related quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in China: A national online survey. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2025, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauta, I.M.; Loughlin, K.N.M.; Gravesteijn, A.S.; van Wegen, J.; Hofman, R.P.; Wilmsen, N.; Coles, E.; van Kempen, Z.L.E.; Killestein, J.; van Oosten, B.W.; et al. A multi–domain lifestyle intervention in multiple sclerosis: A longitudinal observational study. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehanovic, A.; Kunic, S.; Ibrahimagic, O.; Smajlovic, D.; Tupkovic, E.; Mehicevic, A.; Zoletic, E. Contributing factors to the quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Med. Arch. 2020, 74, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabanagic–Hajric, S.; Memic–Serdarevic, A.; Sulejmanpasic, G.; Mehmedika–Suljic, E. Influence of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics on sexual function domains of health related quality of life in multiple sclerosis patients. Mater. Socio–Medica 2022, 34, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhr, L.; Rice, D.R.; Mateen, F.J. Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with depression, anxiety, and general mental health in people with multiple sclerosis during the COVID–19 pandemic. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021, 56, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reece, J.; Yu, M.; Bevens, W.; Simpson-Yap, S.; Davenport, R.; Jelinek, G.; Neate, S. Sociodemographic, health, and lifestyle–related characteristics associated with the commencement and completion of a web–based lifestyle educational program for people with multiple sclerosis: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e58253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, S.; Sandgren, S.; Axelsson, M.; Rosenstein, I.; Lycke, J.; Novakova, L. Quality of life is decreased in persons with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis experiencing progression independent of relapse activity. Mult. Scler. 2025, 31, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broche–Pérez, Y.; Jiménez–Morales, R.M.; Monasterio–Ramos, L.O.; Bauer, J. Psychological Resilience as a Modulator of Cognitive Concerns and Quality of Life in Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñar–Morales, R.; Guirado–Ruíz, P.A.; Barrero–Hernández, F.J. Impacto de la fatiga en la calidad de vida en los adultos con esclerosis múltiple remitente recurrente. Neurología 2024, 40, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobelt, G.; Berg, J.; Lindgren, P.; Fredrikson, S.; Jönsson, B. Costs and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in Europe. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2006, 77, 918–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidao, A.; Jelinek, G.; Simpson–Yap, S.; Neate, S.; Nag, N. Engagement with three or more healthy lifestyle behaviours is associated with improved quality of life over 7.5 years in people with multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2023, 30, 3190–3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañés–Masias, B.; Bort–Roig, J.; Pascual, J.C.; Soler, J.; Briones–Buixassa, L. Online psychological interventions to improve symptoms in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 146, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | M | SD | P25 | P50 | P75 | IL | SL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 38.29 | 10.38 | 30 | 38 | 47 | 19 | 59 | ||

| ≤28 | 7 | 20 | |||||||

| 29–38 | 12 | 34.3 | |||||||

| ≥39 | 16 | 45.7 | |||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Women | 20 | 57.1 | |||||||

| Men | 15 | 42.9 | |||||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Caucasian | 35 | 100 | |||||||

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Student | 8 | 22.9 | |||||||

| Pensioner | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Employee | 15 | 42.9 | |||||||

| Self-Employed | 11 | 31.4 | |||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Married | 19 | 54.3 | |||||||

| In a Domestic Partnership | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| Single | 14 | 40 | |||||||

| Educational Level | |||||||||

| High School Diploma | 4 | 11.4 | |||||||

| Intermediate Vocational Training | 4 | 11.4 | |||||||

| Advanced Vocational Training | 5 | 14.3 | |||||||

| Secondary Education | 8 | 22.9 | |||||||

| University Degree | 14 | 40 | |||||||

| Annual Income Level | 17,062.86 | 14,842.21 | 2200 | 17,000 | 27,000 | 0 | 60,000 | ||

| <€12,450 | 14 | 40 | |||||||

| €12,450–20,200 | 7 | 20 | |||||||

| €20,200–35,200 | 11 | 31.4 | |||||||

| €35,200–60,000 | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| €60,000–300,000 | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| >€300,000 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Family History | |||||||||

| No | 28 | 80 | |||||||

| Yes | 7 | 20 | |||||||

| Previous Mononucleosis | |||||||||

| No | 33 | 94.3 | |||||||

| Yes | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| Autoimmune Diseases | |||||||||

| No | 29 | 82.9 | |||||||

| Yes | 6 | 17.1 | |||||||

| Pregnancy Planning | |||||||||

| No | 32 | 91.4 | |||||||

| Yes | 3 | 8.6 | |||||||

| Tobacco | |||||||||

| No | 27 | 77.1 | |||||||

| Yes | 8 | 22.9 | |||||||

| Alcohol | |||||||||

| No | 32 | 91.4 | |||||||

| Yes | 3 | 8.6 | |||||||

| Other Substances | |||||||||

| No | 34 | 97.1 | |||||||

| Yes (Cannabis) | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Initial Symptoms | |||||||||

| Visual Disturbance | 7 | 20 | |||||||

| Weakness | 4 | 11.4 | |||||||

| Diplopia | 6 | 17.1 | |||||||

| Hypoesthesia | 11 | 31.4 | |||||||

| Paresthesia | 7 | 20 | |||||||

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging | |||||||||

| Yes | 35 | 100 | |||||||

| Treatment | |||||||||

| Alemtuzumab | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Cladribina | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| Corticosteroids | 3 | 8.6 | |||||||

| Diroximel fumarate | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| Lemtrada | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Mavenclad | 5 | 14.3 | |||||||

| Ocrelizumab | 7 | 20 | |||||||

| Ocrevus | 2 | 5.7 | |||||||

| Ofatumumab | 3 | 8.6 | |||||||

| Ponesimod | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Tecfidera | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Tysabri | 5 | 14.3 | |||||||

| Ublituximab | 1 | 2.9 | |||||||

| Vumerity | 1 | 2.9 |

| Domain | Diagnosis Measures | 3 Months Follow-Up Measures | 6 Months Follow-Up Measures | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean ± SD | Effect Size (d) | t | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | Sig. (Two-Tailed) | Mean ± SD | Effect Size (d) | t | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | Sig. (Two-Tailed) | |

| Physical function | 80.67 | 17.67 | 83.14 ± 13.13 | −0.159 | −0.664 | (−0.49, 0.17) | 0.89 | 81.52 ± 12.71 | −0.055 | −0.231 | (−0.39, 0.28) | 1 |

| Physical limitations | 59.57 | 25.79 | 57.43 ± 22.17 | 0.089 | 0.372 | (−0.24, 0.42) | 0.51 | 57.43 ± 21.50 | 0.090 | 0.377 | (−0.24, 0.42) | 0.82 |

| Emotional limitations | 64.38 | 23.03 | 61.52 ± 24.74 | 0.120 | 0.501 | (−0.21, 0.45) | 0.71 | 58.86 ± 20.48 | 0.253 | 1.060 | (−0.08, 0.58) | 0.71 |

| Pain | 78.93 | 23.59 | 80.71 ± 22.40 | −0.077 | −0.324 | (−0.41, 0.25) | 0.62 | 81.79 ± 20.52 | −0.129 | −0.541 | (−0.46, 0.20) | 0.29 |

| Mental health | 44.34 | 14.49 | 57.03 ± 17.17 | −0.799 | −3.342 | (−1.13, −0.47) | 0.75 | 55.09 ± 15.16 | −0.725 | −3.033 | (−1.06, −0.39) | 0.59 |

| Energy | 54.86 | 20.27 | 55.20 ± 18.63 | −0.017 | −0.073 | (−0.35, 0.31) | 0.001 | 55.20 ± 15.91 | −0.019 | −0.078 | (−0.35, 0.31) | 0.001 |

| Health Perception | 48.11 | 18.99 | 47.54 ± 16.77 | 0.032 | 0.133 | (−0.30, 0.36) | 0.94 | 48.91 ± 17.16 | −0.044 | −0.185 | (−0.38, 0.29) | 0.94 |

| Social function | 70.48 | 16.67 | 66.86 ± 15.55 | 0.225 | 0.939 | (−0.11, 0.56) | 0.89 | 65.52 ± 12.78 | 0.334 | 1.397 | (0.00, 0.67) | 0.85 |

| Cognitive function | 70.12 | 21.40 | 69.04 ± 19.78 | 0.052 | 0.219 | (−0.28, 0.38) | 0.35 | 67.50 ± 19.30 | 0.129 | 0.538 | (−0.20, 0.46) | 0.17 |

| Stress | 44.29 | 22.51 | 47.38 ± 18.40 | −0.150 | −0.629 | (−0.48, 0.18) | 0.83 | 48.95 ± 17.84 | −0.229 | −0.960 | (−0.56, 0.10) | 0.59 |

| Sexual function | 79.46 | 17.12 | 78.21 ± 18.96 | 0.069 | 0.289 | (−0.26, 0.40) | 0.53 | 78.93 ± 18.25 | 0.030 | 0.125 | (−0.30, 0.36) | 0.34 |

| Health changes | 37.71 | 18.00 | 45.71 ± 24.05 | −0.377 | −1.576 | (−0.71, −0.05) | 0.77 | 49.71 ± 23.95 | −0.566 | −2.370 | (−0.90, −0.24) | 0.9 |

| Satisfaction with Sexual Life | 65.14 | 23.93 | 65.71 ± 20.33 | −0.026 | −0.107 | (−0.36, 0.31) | 0.12 | 65.14 ± 20.20 | 0.000 | 0.000 | (−0.33, 0.33) | 0.02 |

| Perceived Quality of Life | 62.39 | 14.15 | 62.85 ± 12.71 | −0.034 | −0.143 | (−0.37, 0.30) | 0.92 | 62.39 ± 11.77 | 0.000 | 0.000 | (−0.33, 0.33) | 1 |

| Domain | Mean ± SD (3 Months) | Mean ± SD (6 Months) | Effect Size (d) | t | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | Sig. (Two-Tailed) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 83.14 ± 13.13 | 81.52 ± 12.71 | 0.125 | 2.682 | (−0.688, 0.939) | 0.007 |

| Physical limitations | 57.43 ± 22.17 | 57.43 ± 21.5 | 0.0 | 0.407 | (−1.374, 1.374) | 0.684 |

| Emotional limitations | 61.52 ± 24.74 | 58.86 ± 20.48 | 0.117 | 3.847 | (−1.416, 1.651) | 0.0 |

| Pain | 80.71 ± 22.4 | 81.79 ± 20.52 | −0.05 | −0.897 | (−1.439, 1.338) | 0.37 |

| Mental health | 57.03 ± 17.17 | 55.09 ± 15.16 | 0.12 | 5.335 | (−0.944, 1.184) | 0.0 |

| Energy | 55.2 ± 18.63 | 55.2 ± 15.91 | 0.0 | −0.66 | (−1.155, 1.155) | 0.51 |

| Health Perception | 47.54 ± 16.77 | 48.91 ± 17.16 | −0.081 | −2.357 | (−1.12, 0.959) | 0.019 |

| Social function | 66.86 ± 15.55 | 65.52 ± 12.78 | 0.094 | 1.567 | (−0.87, 1.058) | 0.118 |

| Cognitive function | 69.04 ± 19.78 | 67.5 ± 19.3 | 0.079 | 2.504 | (−1.147, 1.305) | 0.012 |

| Stress | 47.38 ± 18.4 | 48.95 ± 17.84 | −0.087 | −1.61 | (−1.227, 1.054) | 0.108 |

| Sexual function | 78.21 ± 18.96 | 78.93 ± 18.25 | −0.039 | −0.406 | (−1.214, 1.136) | 0.684 |

| Health changes | 45.71 ± 24.05 | 49.71 ± 23.95 | −0.167 | −4.091 | (−1.657, 1.324) | 0.0 |

| Satisfaction with Sexual Life | 65.71 ± 20.33 | 65.14 ± 20.2 | 0.028 | −0.024 | (−1.232, 1.288) | 0.981 |

| Perceived Quality of Life | 62.85 ± 12.71 | 62.39 ± 11.77 | 0.038 | 0.639 | (−0.75, 0.825) | 0.523 |

| MSQOL-54 at Diagnosis | MSQOL-54 at 3 Months | MSQOL-54 at 6 Months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSQOL-54 at diagnosis | Correlation Coefficient | 1 | ||

| Sig. (two-tailed) | ||||

| MSQOL-54 at 3 months | Correlation Coefficient | 0.909 ** | 1 | |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.001 | |||

| MSQOL-54 at 6 months | Correlation Coefficient | 0.888 ** | 0.933 ** | 1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.001 | ||

| Domain | Mean ± SD | Mean Difference | 95% CI (Lower, Upper) | t | Sig. (Two-Tailed) | Effect Size (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Life (Diagnosis vs. 3 months) | 62.4 ± 14.15 vs. 62.85 ± 12.72 | −0.45 | (−2.47, 1.58) | −0.448 | 0.657 | 0.08 |

| Quality of Life (Diagnosis vs. 6 months) | 62.4 ± 14.15 vs. 62.39 ± 11.77 | 0.01 | (−2.24, 2.27) | 0.010 | 0.992 | 0.00 |

| Quality of Life (3 months vs. 6 months) | 62.85 ± 12.72 vs. 62.39 ± 11.77 | 0.46 | (−1.12, 2.03) | 0.590 | 0.559 | 0.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pego Pérez, E.R.; Bermello López, M.L.; Gómez Fernández, E.; Marín Arnés, M.d.R.; Fernández Vázquez, M.; Núñez Hernández, M.I.; Gutiérrez García, E. Predicting Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Burden Meets Emotional Balance in Early Disease. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120195

Pego Pérez ER, Bermello López ML, Gómez Fernández E, Marín Arnés MdR, Fernández Vázquez M, Núñez Hernández MI, Gutiérrez García E. Predicting Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Burden Meets Emotional Balance in Early Disease. Neurology International. 2025; 17(12):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120195

Chicago/Turabian StylePego Pérez, Emilio Rubén, María Lourdes Bermello López, Eva Gómez Fernández, María del Rosario Marín Arnés, Mercedes Fernández Vázquez, María Irene Núñez Hernández, and Emilio Gutiérrez García. 2025. "Predicting Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Burden Meets Emotional Balance in Early Disease" Neurology International 17, no. 12: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120195

APA StylePego Pérez, E. R., Bermello López, M. L., Gómez Fernández, E., Marín Arnés, M. d. R., Fernández Vázquez, M., Núñez Hernández, M. I., & Gutiérrez García, E. (2025). Predicting Quality of Life in Relapsing–Remitting Multiple Sclerosis: Clinical Burden Meets Emotional Balance in Early Disease. Neurology International, 17(12), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120195