Progressive Unilateral Moyamoya-like Vasculopathy After Head Trauma with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Case Demonstrating the Utility of Anterior Circulation Basi-Parallel Anatomical Scanning

Abstract

1. Introduction

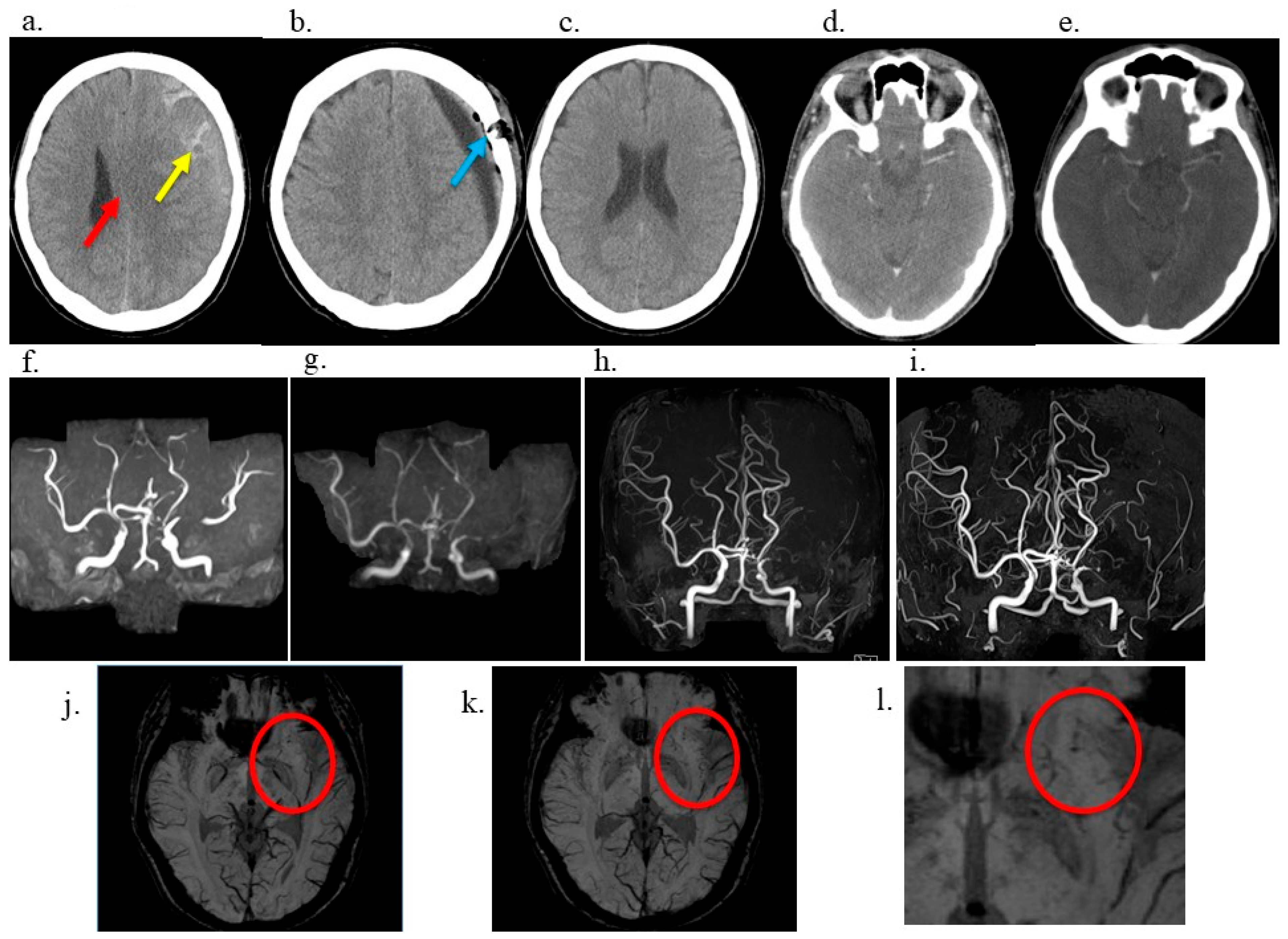

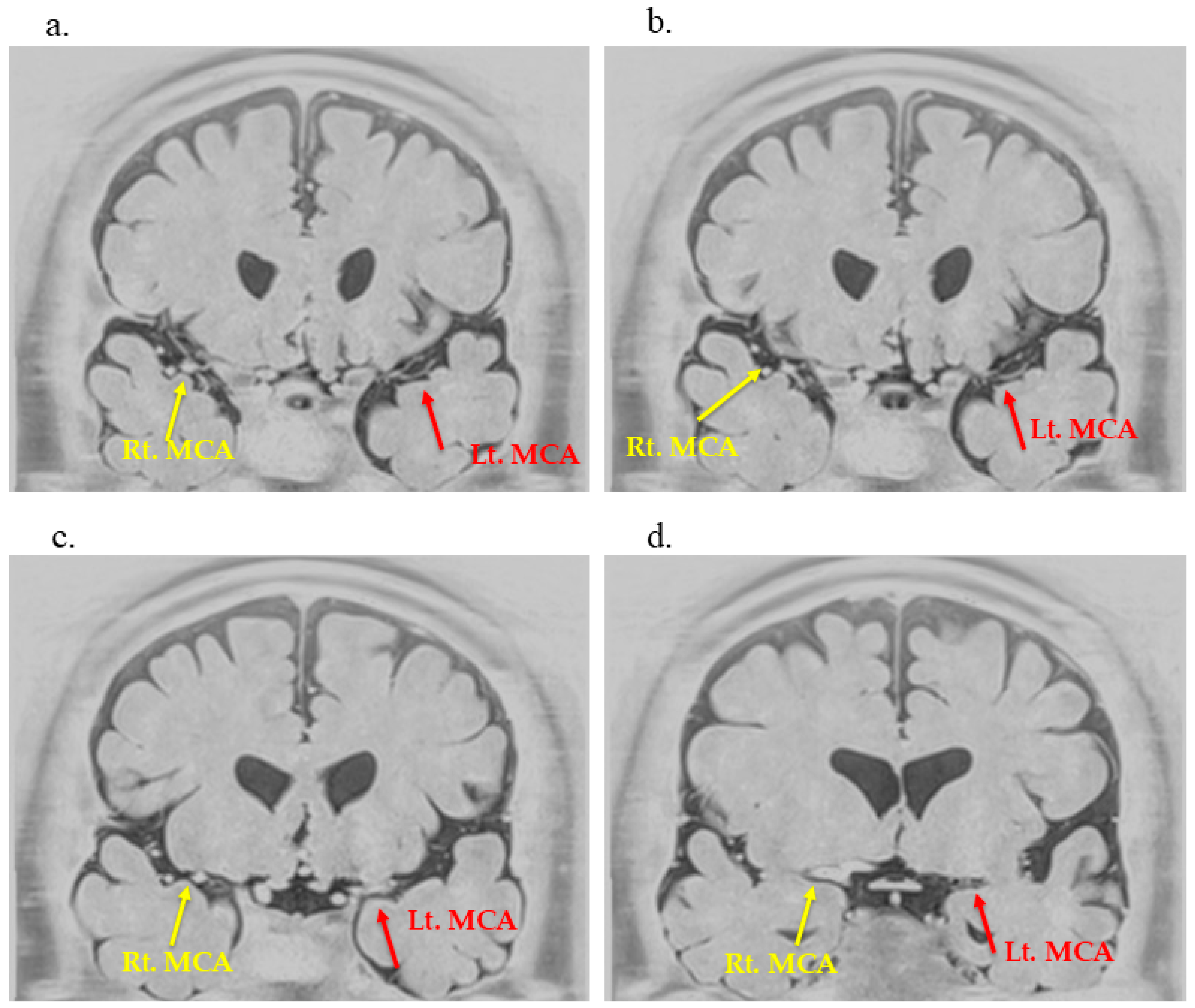

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

3.1. Previous Context Reported and Uniqueness of This Case

3.2. Potential Etiologies and Risk Factors

3.2.1. Overview of Possible Mechanisms

3.2.2. Endothelial Injury Hypothesis

3.2.3. Hemodynamic Redistribution Hypothesis

3.2.4. Chronic Inflammation Hypothesis

3.3. Utility of BPAS in Detecting Moyamoya-like Vascular Changes

3.4. Limitations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPAS | Basi-parallel Anatomic Scanning magnetic resonance imaging |

| CARE | Case Report |

| CSDH | Chronic Subdural Hematoma |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| ICA | Internal Carotid Artery |

| MCA | Middle Cerebral Artery |

| MRA | Magnetic Resonance Angiography |

| TOF | Time-of-Flight |

| mRS | Modified Rankin Scale |

| SWI | Susceptibility-Weighted Imaging |

References

- Gonzalez, N.R.; Amin-Hanjani, S.; Bang, O.Y.; Coffey, C.; Du, R.; Fierstra, J.; Fraser, J.F.; Kuroda, S.; Tietjen, G.E.; Yaghi, S.; et al. Adult Moyamoya disease and syndrome: Current perspectives and future directions: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2023, 54, e465–e479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velo, M.; Grasso, G.; Fujimura, M.; Torregrossa, F.; Longo, M.; Granata, F.; Pitrone, A.; Vinci, S.L.; Ferraù, L.; La Spina, P. Moyamoya Vasculopathy: Cause, Clinical Manifestations, Neuroradiologic Features, and Surgical Management. World Neurosurg. 2022, 159, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, S.; Fujimura, M.; Takahashi, J.; Kataoka, H.; Ogasawara, K.; Iwama, T.; Tominaga, T.; Miyamoto, S. Research Committee on Moyamoya Disease (Spontaneous Occlusion of Circle of Willis) of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, Japan. Diagnostic criteria for Moyamoya disease—2021 revised version. Neurol. Med. Chir. 2022, 62, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Alvarez, E.; Pineda, M.; Royo, C.; Manzanares, R. ‘Moya-moya’ disease caused by cranial trauma. Brain Dev. 1979, 1, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaletel, M.; Surlan-Popović, K.; Pretnar-Oblak, J.; Zvan, B. Moyamoya syndrome with arteriovenous dural fistula after head trauma. Acta Clin. Croat. 2011, 50, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahata, M.; Abe, Y.; Ono, S.; Hosoya, T.; Uno, S. Surface appearance of the vertebrobasilar artery revealed on basiparallel anatomic scanning (BPAS)-MR imaging: Its role for brain MR examination. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2005, 26, 2508–2513. [Google Scholar]

- van Swieten, J.C.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Visser, M.C.; Schouten, H.J.; van Gijn, J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988, 19, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifino, N.; Hervé, D.; Acerbi, F.; Kuroda, S.; Lanzino, G.; Vajkoczy, P.; Bersano, A. Diagnosis and management of adult moyamoya angiopathy: An overview of guideline recommendations and identification of future research directions. Int. J. Stroke 2025, 20, 512–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-C.; Yang, Y.; Dong, J.; Sun, Z.-Q.; Ran, Q.-S.; Li, W.; Jin, W.-S.; Zhang, M. MCA Parallel Anatomic Scanning MR Imaging-Guided Recanalization of a Chronic Occluded MCA by Endovascular Treatment. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2024, 45, 1227–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, G.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Gao, L.; Gao, G.; Tan, G.; Yuan, T. Refined imaging features of culprit plaques improve the prediction of recurrence in intracranial atherosclerotic stroke within the middle cerebral artery territory. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 39, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, S.; Nawashiro, H.; Uozumi, Y.; Otani, N.; Osada, H.; Wada, K.; Shima, K. Chronic Subdural Hematoma Associated With Moyamoya Disease. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2014, 9, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Miyazaki, H.; Iino, N.; Shiokawa, Y.; Saito, I. Acute carotid arterial occlusion after burr hole surgery for chronic subdural haematoma in moyamoya disease. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2004, 11, 778–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura, M.; Nojiri, K. Resolved chronic subdural hematoma associated with acute subdural hematoma in moyamoya disease. Neurol. Med. Chir. 1984, 24, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, N.; Morikawa, M.; Nozaki, A.; Hayashi, K.; Suyama, K.; Nagata, I. ‘Brush Sign’ on susceptibility-weighted MR imaging indicates the severity of Moyamoya disease. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2011, 32, 1697–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, B.M.; Dorschel, K.B.; Lawton, M.T.; Wanebo, J.E. Pathophysiology of Vascular Stenosis and Remodeling In Moyamoya Disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 661578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, D.F., III; Srivikram Margam, S.; Gustin, A.; Gustin, P.J.; Jajeh, M.N.; Chavis, Y.C.; Walker, K.V.; Bentley, J.S. Case Report: A Rare Presentation of Rapidly Progressive Moyamoya Disease Refractory To Unilateral Surgical Revascularization. Front. Surg. 2024, 11, 1409692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januschek, E.; Fujimura, M.; Mugikura, S.; Tominaga, T. Progressive Moyamoya Syndrome Associated With De Novo Formation of The Ipsilateral Venous and Contralateral Cavernous Malformations: Case Report. Surg. Neurol. 2008, 69, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Wu, B.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, S.; Liu, M. Association of Moyamoya disease with thyroid autoantibodies and thyroid function: A case-control study and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Neurol. 2014, 21, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, T.; Okune, S.; Tanaka, S.; Yamagami, H.; Matsumaru, Y. RNF213-Related Vasculopathy: An Entity with Diverse Phenotypic Expressions. Genes 2025, 16, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otten, E.G.; Werner, E.; Crespillo-Casado, A.; Boyle, K.B.; Dharamdasani, V.; Pathe, C.; Santhanam, B.; Randow, F. Ubiquitylation of lipopolysaccharide by RNF213 during bacterial infection. Nature 2021, 594, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Heo, K.G.; Shin, H.Y.; Bang, O.Y.; Kim, G.M.; Chung, C.S.; Kim, K.H.; Jeon, P.; Kim, J.S.; Hong, S.C.; et al. Association of thyroid autoantibodies with moyamoya-type cerebrovascular disease: A prospective study. Stroke 2010, 41, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihara, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Hattori, Y.; Liu, W.; Kobayashi, H.; Ishiyama, H.; Yoshimoto, T.; Miyawaki, S.; Clausen, T.; Bang, O.Y.; et al. Moyamoya disease: Diagnosis and interventions. Lancet Neurol. 2022, 21, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimonova, E.; Ovsiannikov, K.; Rzaev, J. Neuroimaging In Moyamoya Angiopathy: Updated Review. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2022, 222, 107471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Morito, D.; Takashima, S.; Mineharu, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Hitomi, T.; Hashikata, H.; Matsuura, N.; Yamazaki, S.; Toyoda, A.; et al. Identification of RNF213 as a susceptibility gene for Moyamoya disease and its possible role in vascular development. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnier, J.J.; Kienle, G.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; Sox, H.; Riley, D. The CARE guidelines: Consensus-based clinical case reporting guideline development. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, 2, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watanabe, S.; Shibata, Y.; Ishikawa, E. Progressive Unilateral Moyamoya-like Vasculopathy After Head Trauma with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Case Demonstrating the Utility of Anterior Circulation Basi-Parallel Anatomical Scanning. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120191

Watanabe S, Shibata Y, Ishikawa E. Progressive Unilateral Moyamoya-like Vasculopathy After Head Trauma with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Case Demonstrating the Utility of Anterior Circulation Basi-Parallel Anatomical Scanning. Neurology International. 2025; 17(12):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120191

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatanabe, Shinya, Yasushi Shibata, and Eiichi Ishikawa. 2025. "Progressive Unilateral Moyamoya-like Vasculopathy After Head Trauma with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Case Demonstrating the Utility of Anterior Circulation Basi-Parallel Anatomical Scanning" Neurology International 17, no. 12: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120191

APA StyleWatanabe, S., Shibata, Y., & Ishikawa, E. (2025). Progressive Unilateral Moyamoya-like Vasculopathy After Head Trauma with Chronic Subdural Hematoma: A Case Demonstrating the Utility of Anterior Circulation Basi-Parallel Anatomical Scanning. Neurology International, 17(12), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17120191