Study on a Dual-Dimensional Compensation Mechanism and Bi-Level Optimization Approach for Real-Time Electric Vehicle Demand Response in Unified Build-and-Operate Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Framework of the Dual-Dimensional Compensation Mechanism

- (1)

- Monitoring: The power grid monitors the system load in real-time, identifies risks such as peak overload or power supply shortage, and establishes the trigger conditions for DR.

- (2)

- Triggering: The power grid issues real-time demand response instructions to the community EVA, specifying the target load reduction , response duration , and incentive price

- (3)

- Acquisition: Upon receiving the instructions, the EVA collects real-time data from the currently connected contracted users. This data includes user constraints (e.g., vehicle pick-up time, expected and minimum SoC), current charging status, and individual compensation curves.

- (4)

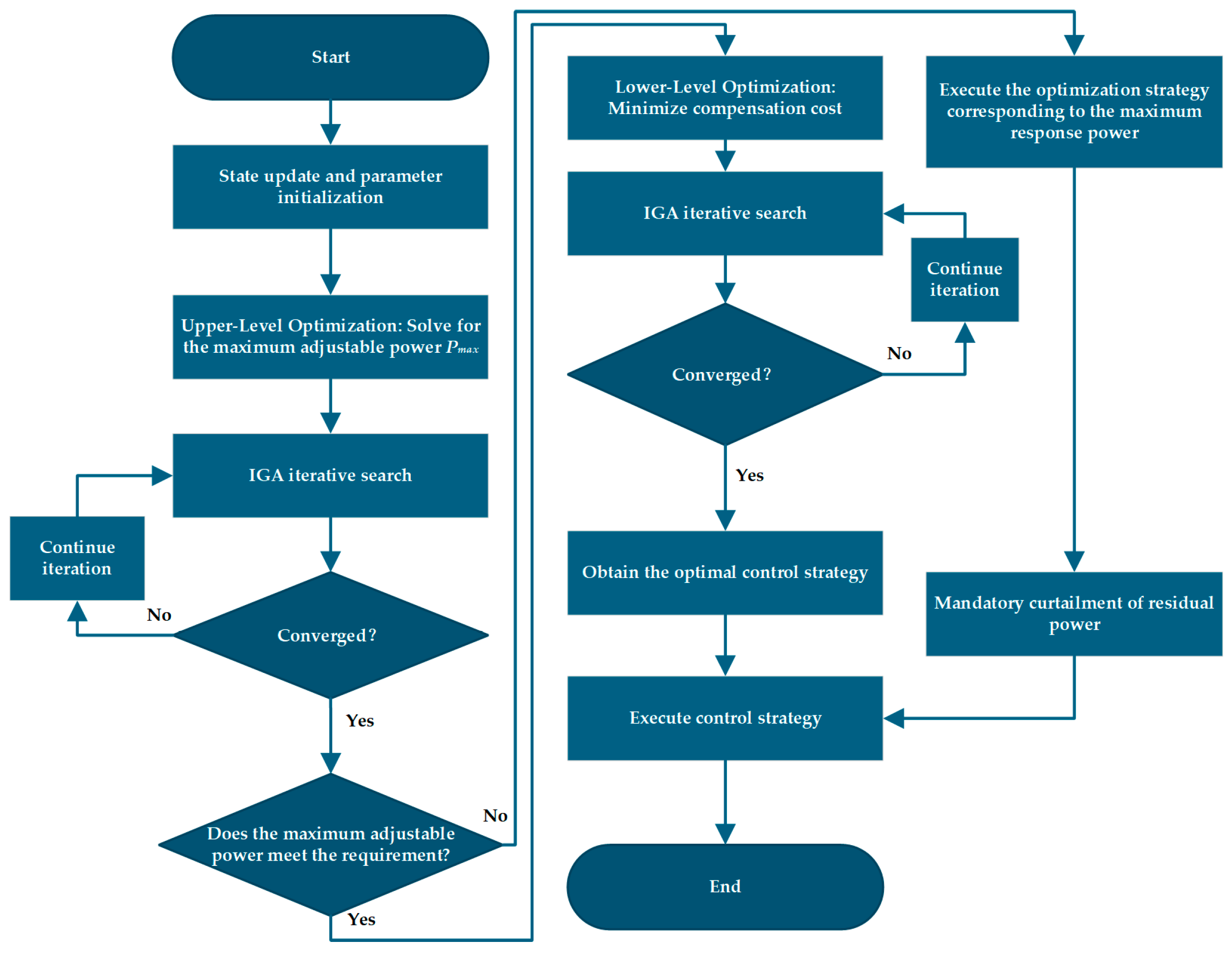

- Formulation: A bi-level optimization model is constructed based on the collected information. The optimal dispatch strategy is then generated by solving the model using the IGA (see Section 3.3):

- (5)

- Response: The EVA delivers the optimized regulation strategy to charging facilities, which execute the adjustment commands.

- (6)

- Settlement: After the response period, the EVA settles compensation fees with users who actively responded in accordance with the compensation standards in the agreement.

- i.

- capacity reservation before the event through contractual commitments,

- ii.

- real-time regulation during the event,

- iii.

- performance-based compensation after the event.

3. The Bi-Level Optimization Model

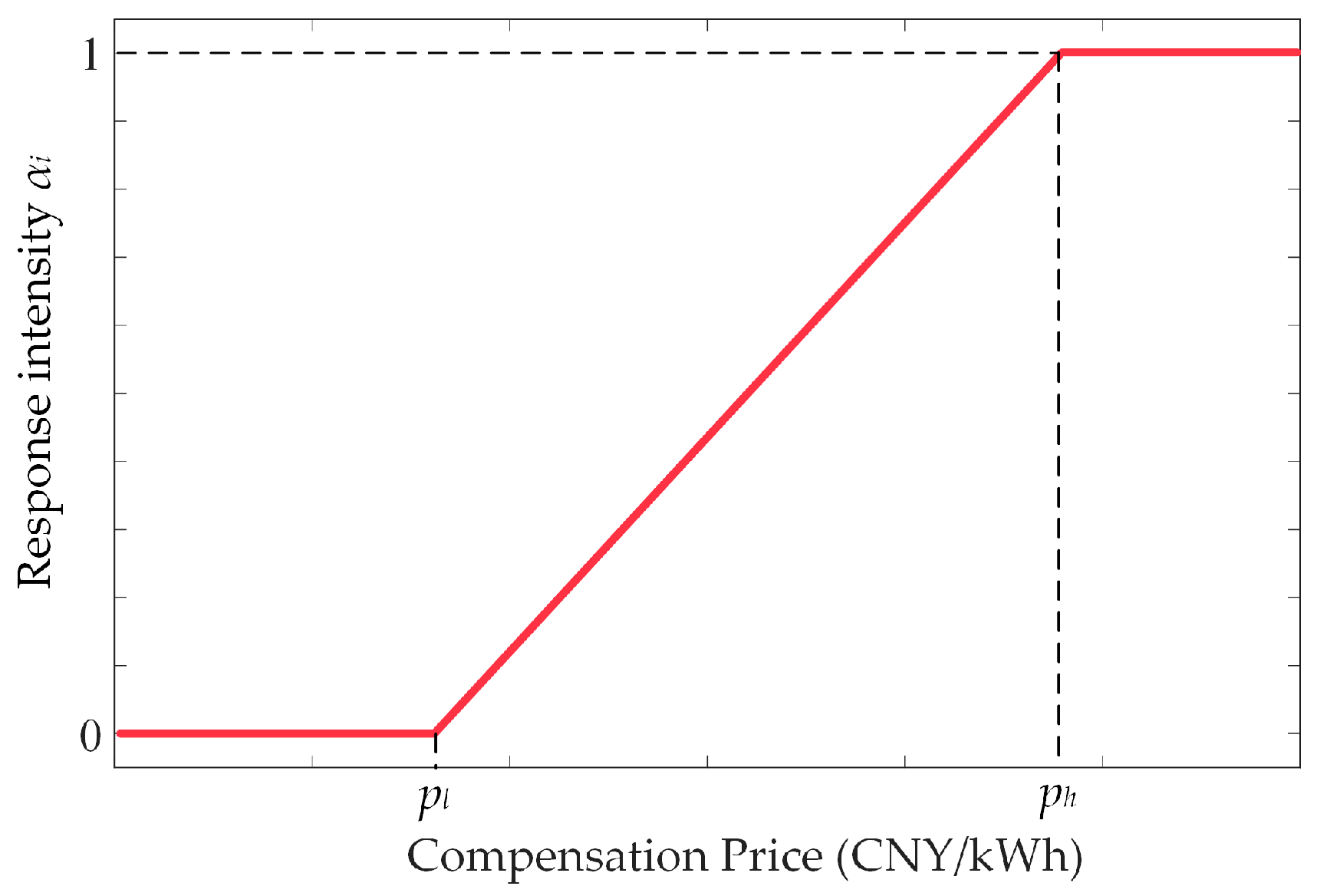

3.1. User Response Model

3.2. Optimization Model

3.2.1. Upper-Level Optimization Model

- Objective Function

- 2.

- Constraints

- (1)

- Total Cost Cap Constraint

- (2)

- Non-Negativity Constraint of Aggregator’s Marginal Revenue

- (3)

- Boundary Constraint on Response Intensity

3.2.2. Lower-Level Optimization Model

- Objective Function

- 2.

- Constraints

- (1)

- Total Regulation Power Requirement

- (2)

- SoC Lower-Bound Constraint

3.3. Solution of Optimization Model

4. Case Study

4.1. Case Setup

4.1.1. Fundamental Assumptions

- (1)

- Simplified User Behavior: Key user behavior parameters are assumed to be either fixed or drawn from a predefined identical distribution.

- (2)

- Simplified Model Parameters: Key simulation parameters, such as the compensation curve, are assumed to be fixed and known during a single simulation run.

- (3)

- Idealized Control Process: The charging equipment providing services for EVs is assumed to have continuously adjustable output power, and communication delays are neglected during the control process.

- (4)

- Simplified Infrastructure Constraints: Practical factors such as heterogeneous charger types, the number of connections per station, charging limitations in high-rise or underground garages, and potential V2G/V2V capabilities are not explicitly modeled, as the simulation focuses on validating the core mechanism.

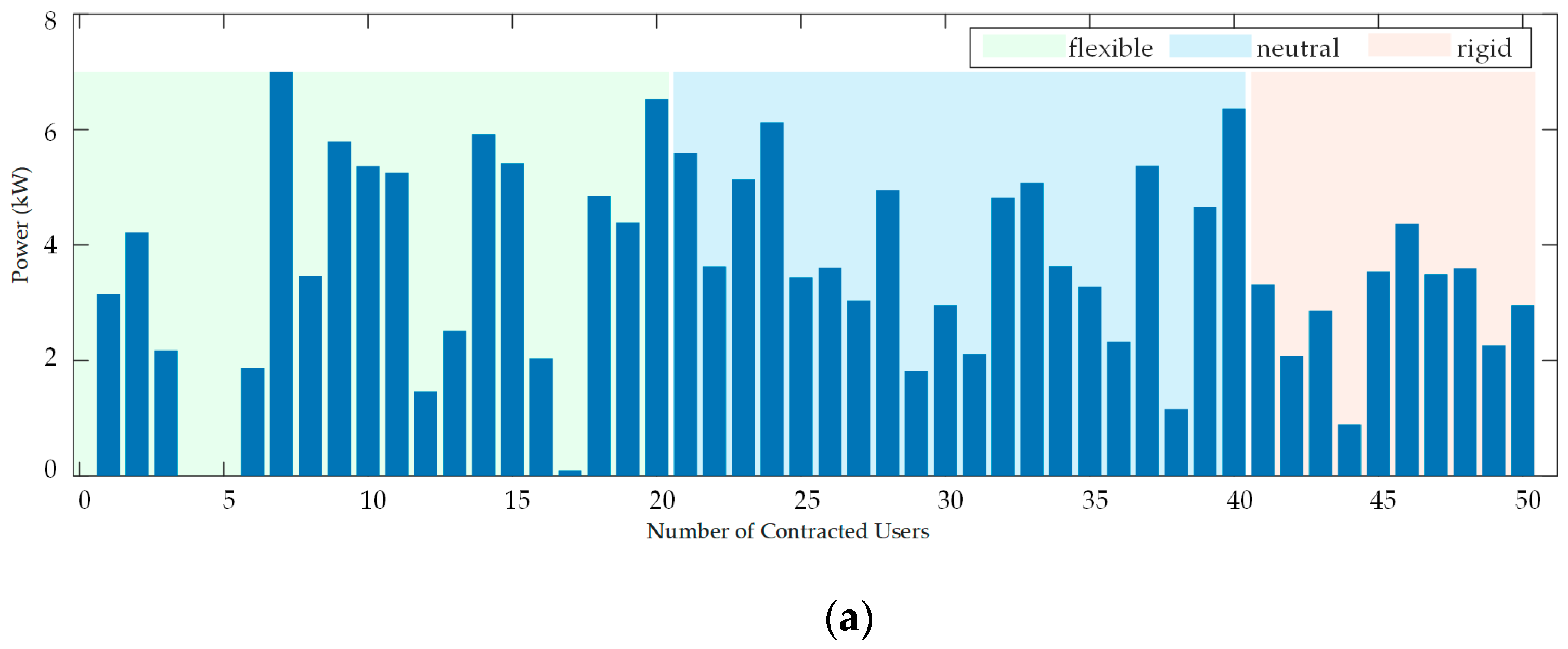

4.1.2. Simulation Scenario Configuration

4.1.3. Comparative Mechanism Design

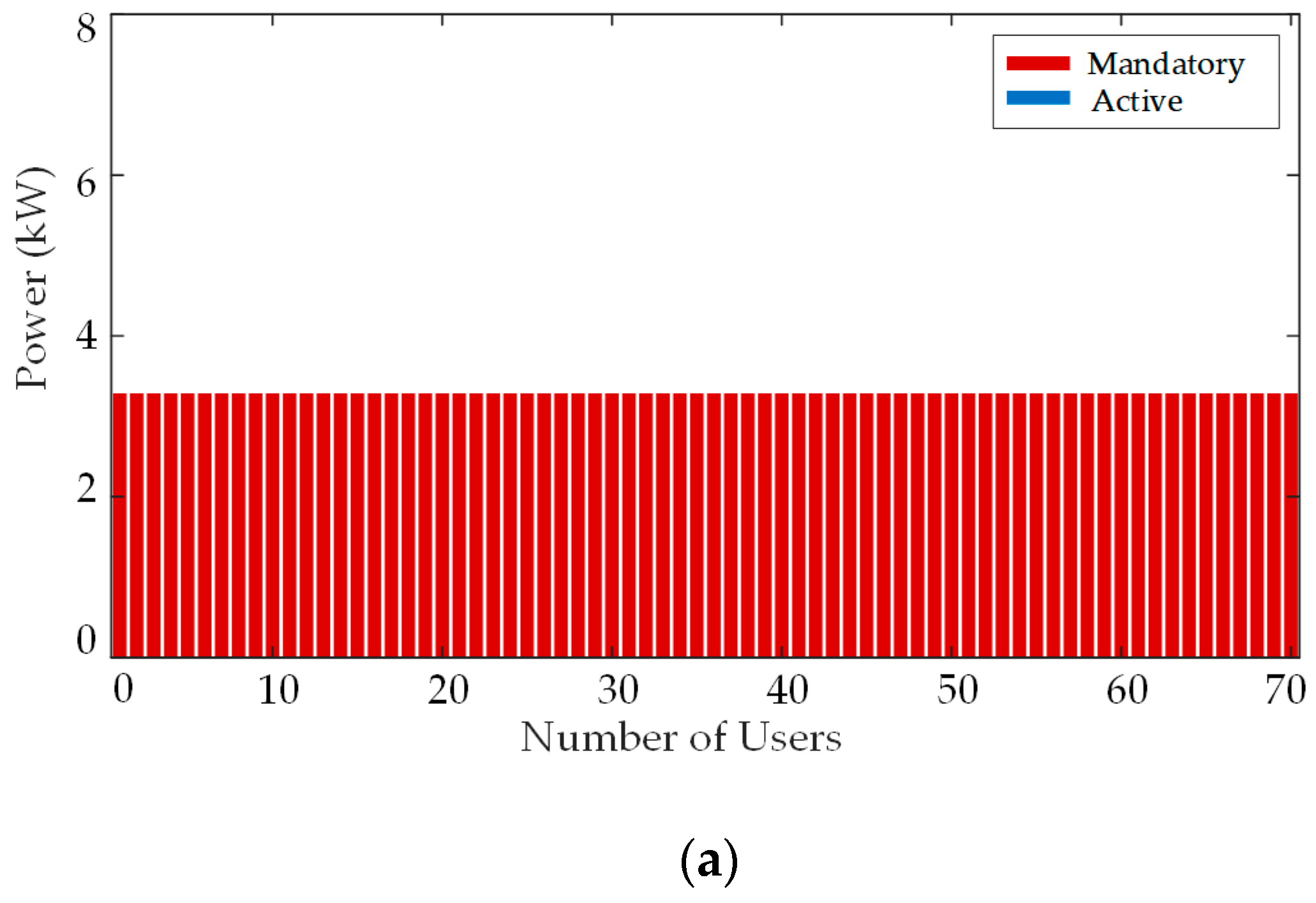

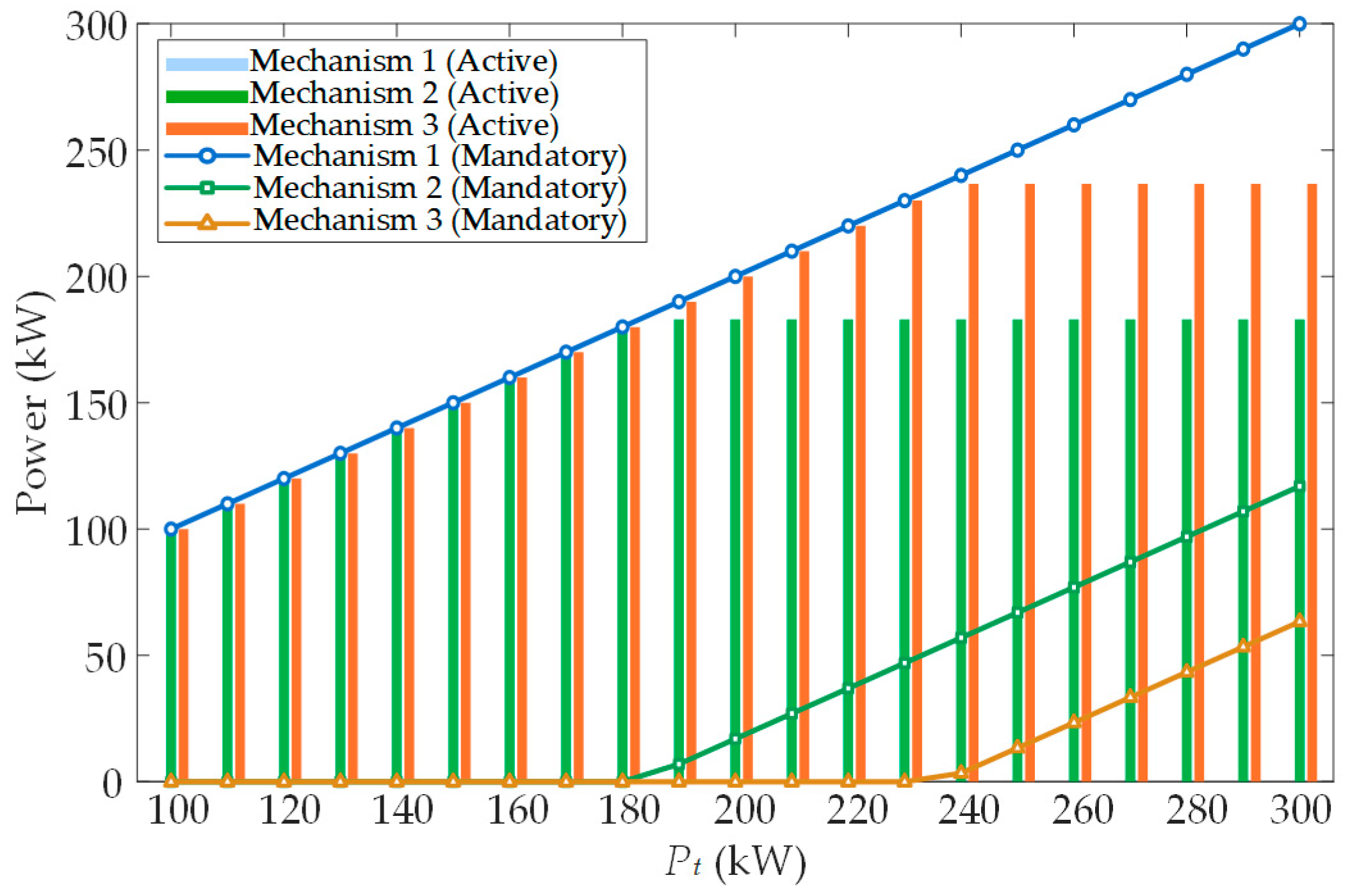

- Mechanism 1 (M1): When the system capacity exceeds limits, the EVA implements a uniform proportional reduction for all users, including both contracted and non-contracted.

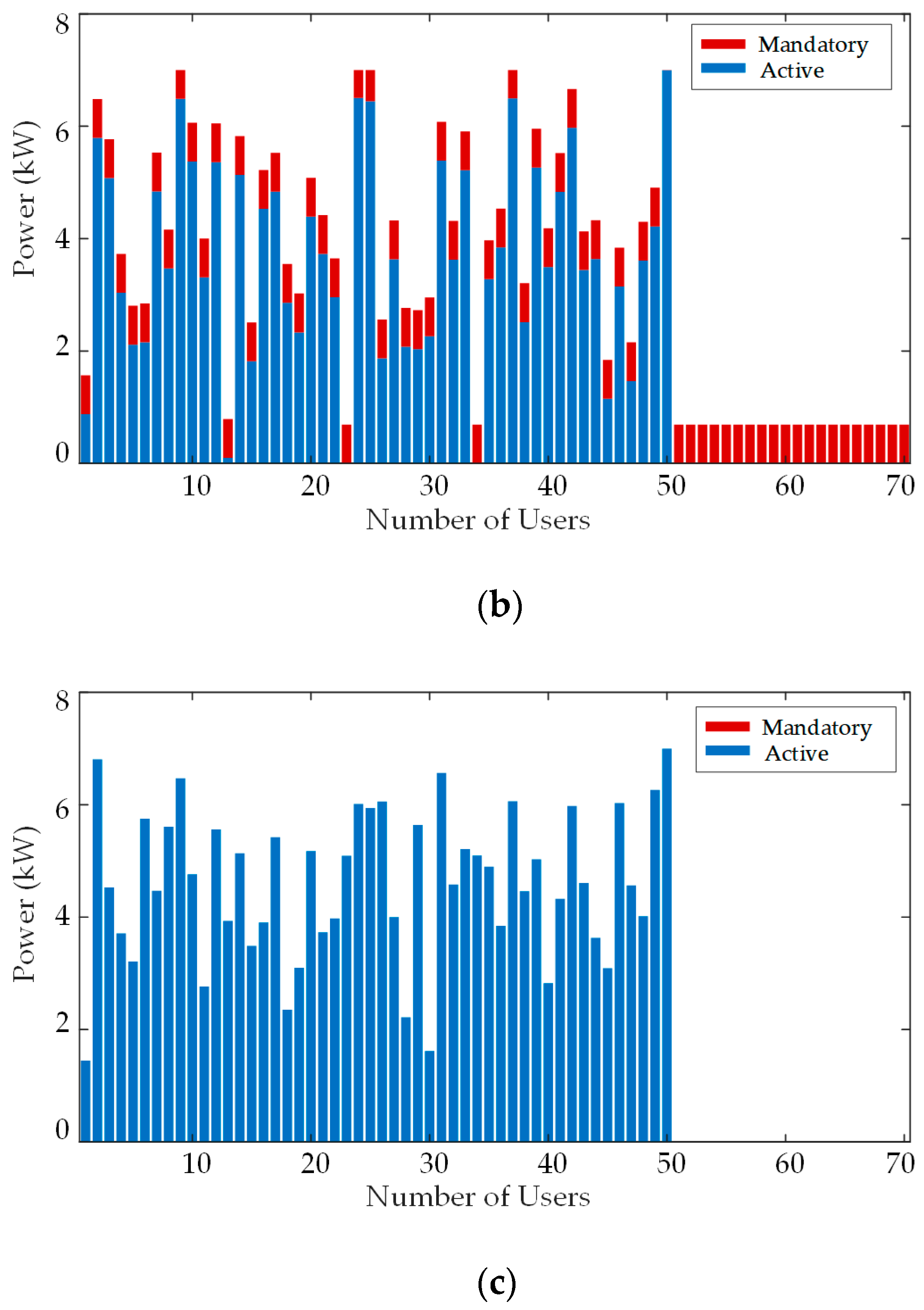

- Mechanism 2 (M2): Contracted users respond actively, and the EVA implements differentiated control according to the signed power regulation and compensation agreement, ensuring the target SoC of users remains unchanged. Any shortfall in active response is compensated via mandatory curtailment.

- Mechanism 3 (M3-Proposed Mechanism): Contracted users respond actively, and the EVA implements differentiated control according to the signed power regulation and SoC loss compensation agreement. Any shortfall in active response is also compensated via mandatory curtailment.

4.1.4. Evaluation Metrics

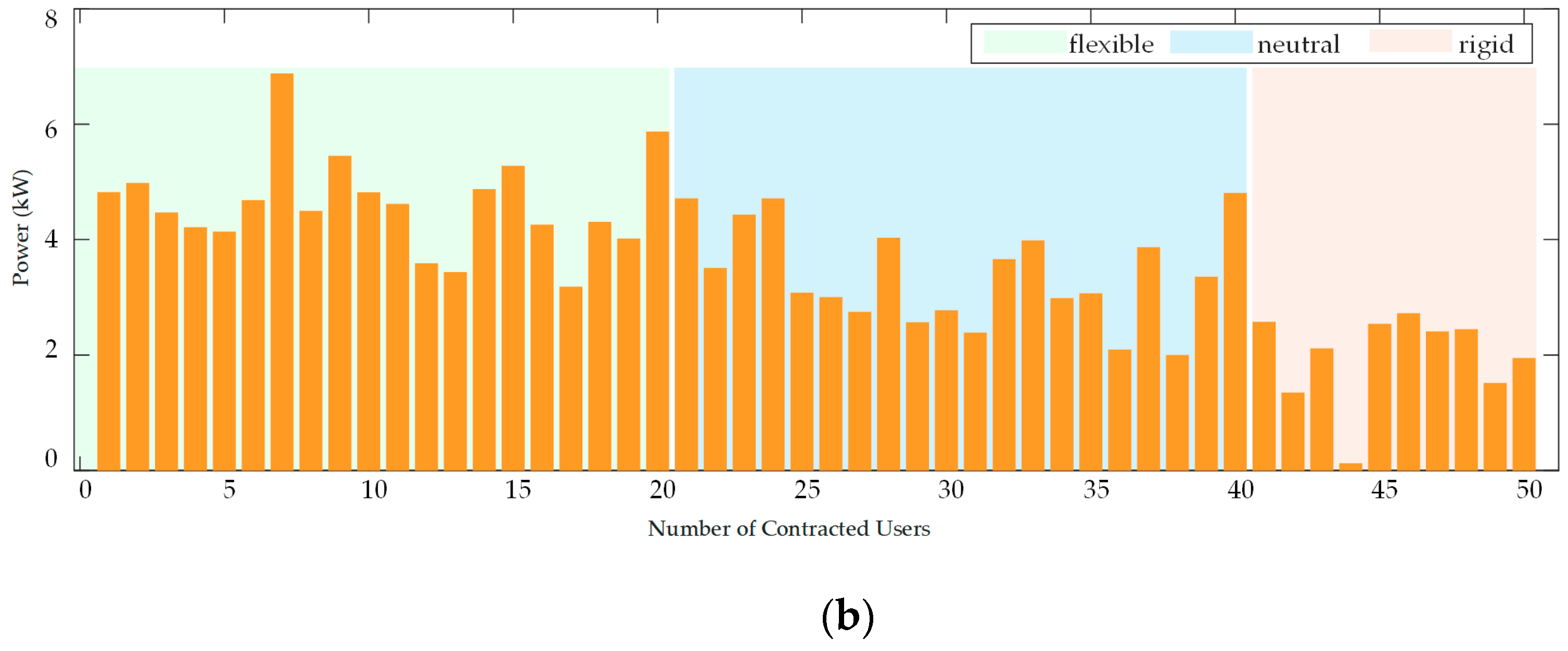

4.2. Analysis of the RTDR Strategy

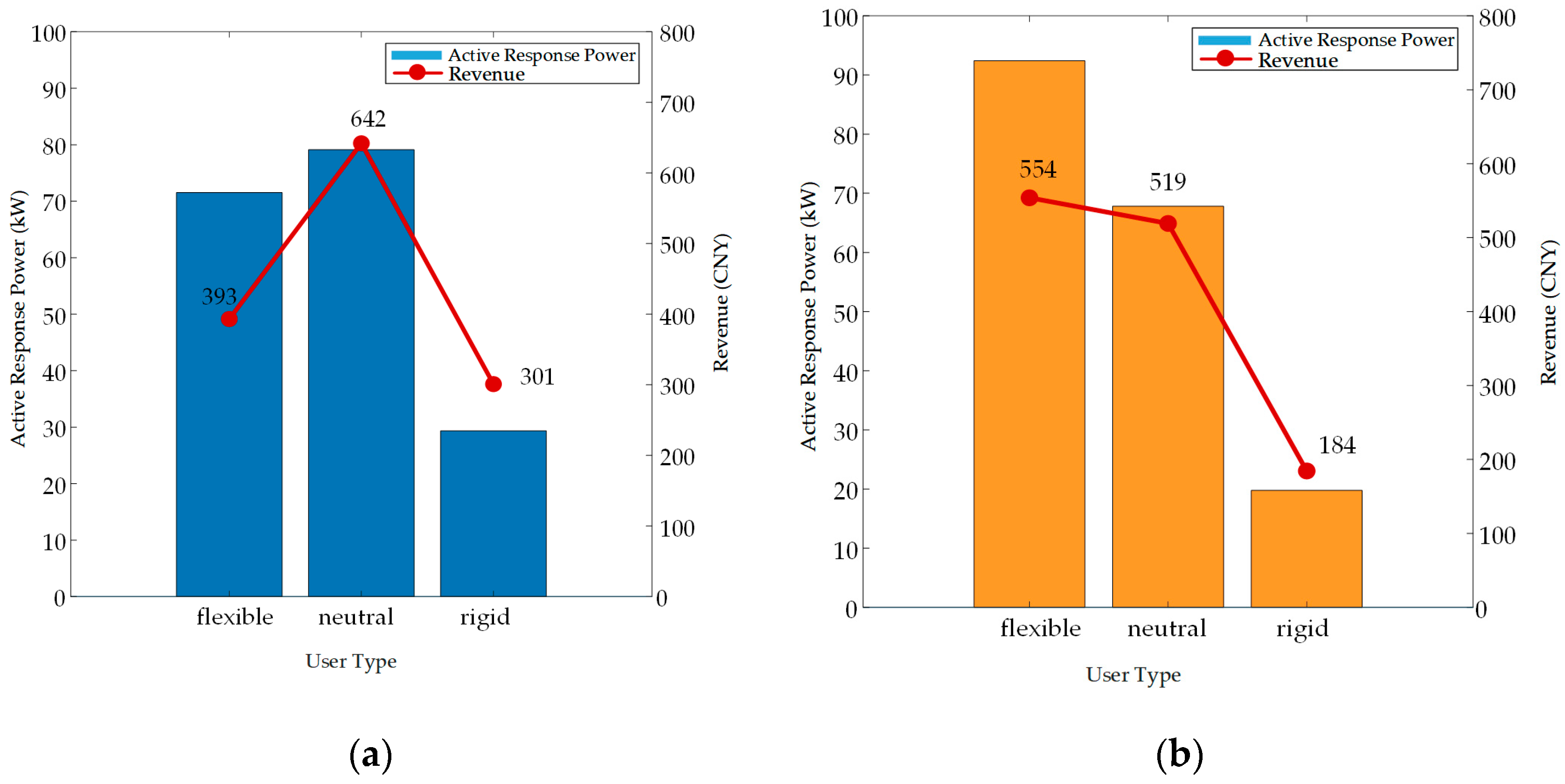

4.3. Analysis of Influencing Factors

4.3.1. Control Potential Analysis

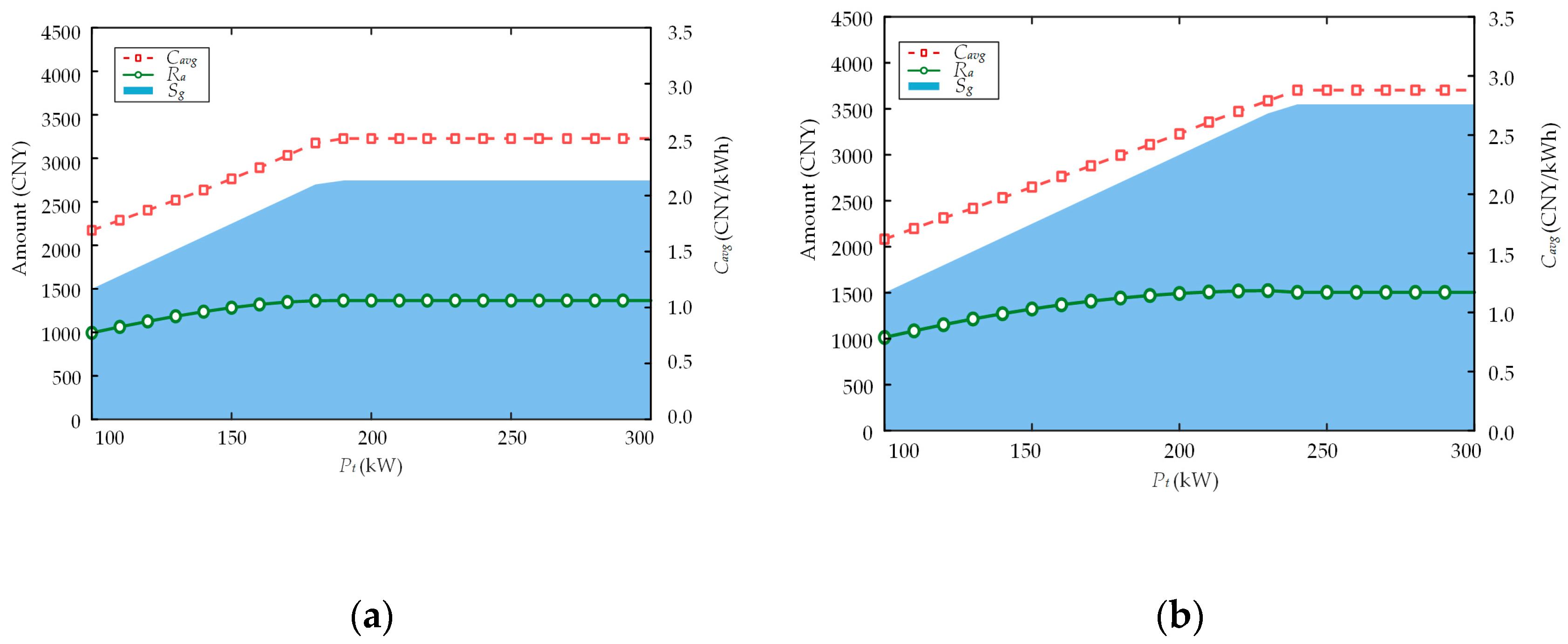

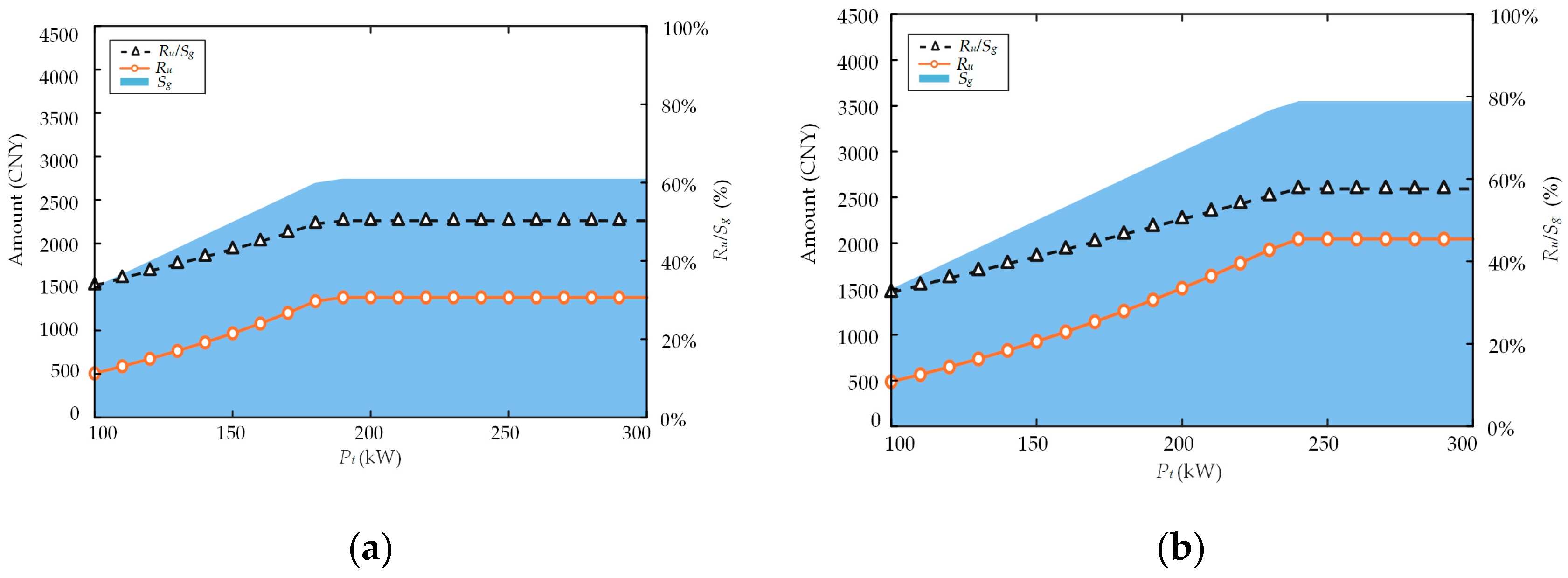

4.3.2. Benefit Analysis

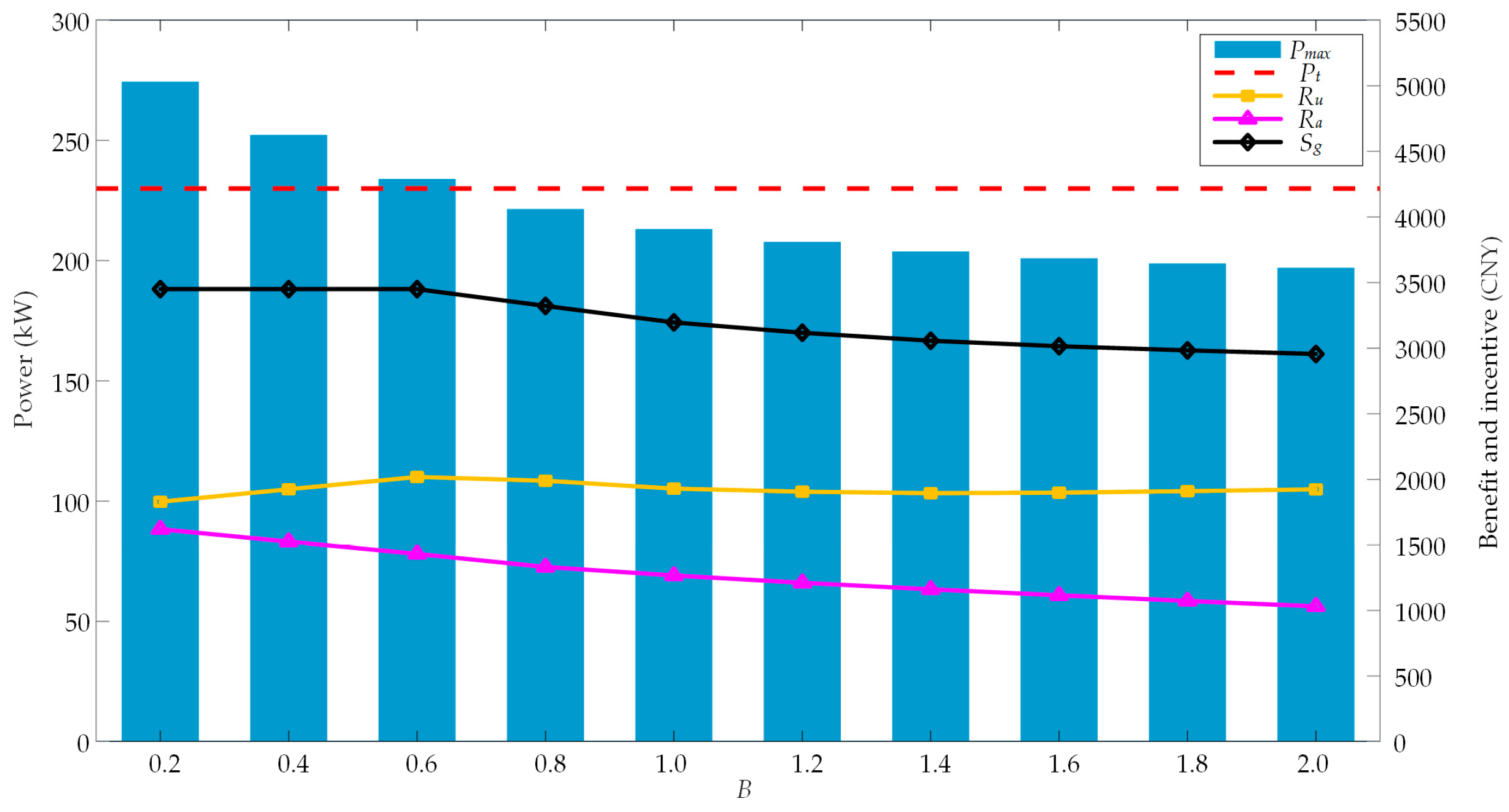

4.3.3. Analysis of SoC Loss Compensation Coefficient

4.3.4. Target SoC Analysis

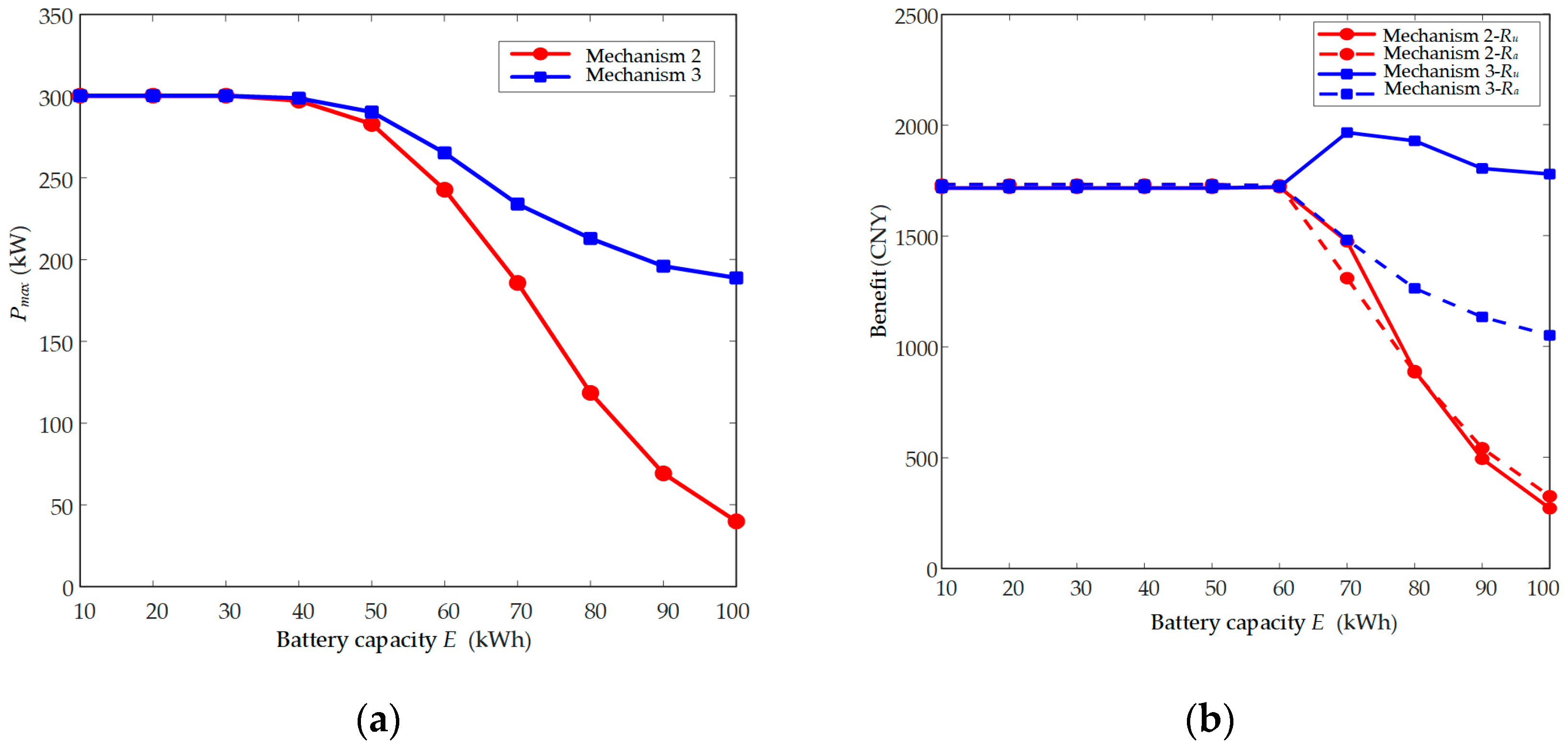

4.3.5. Analysis of Battery Capacity

4.3.6. Analysis of Subsidy Coefficient

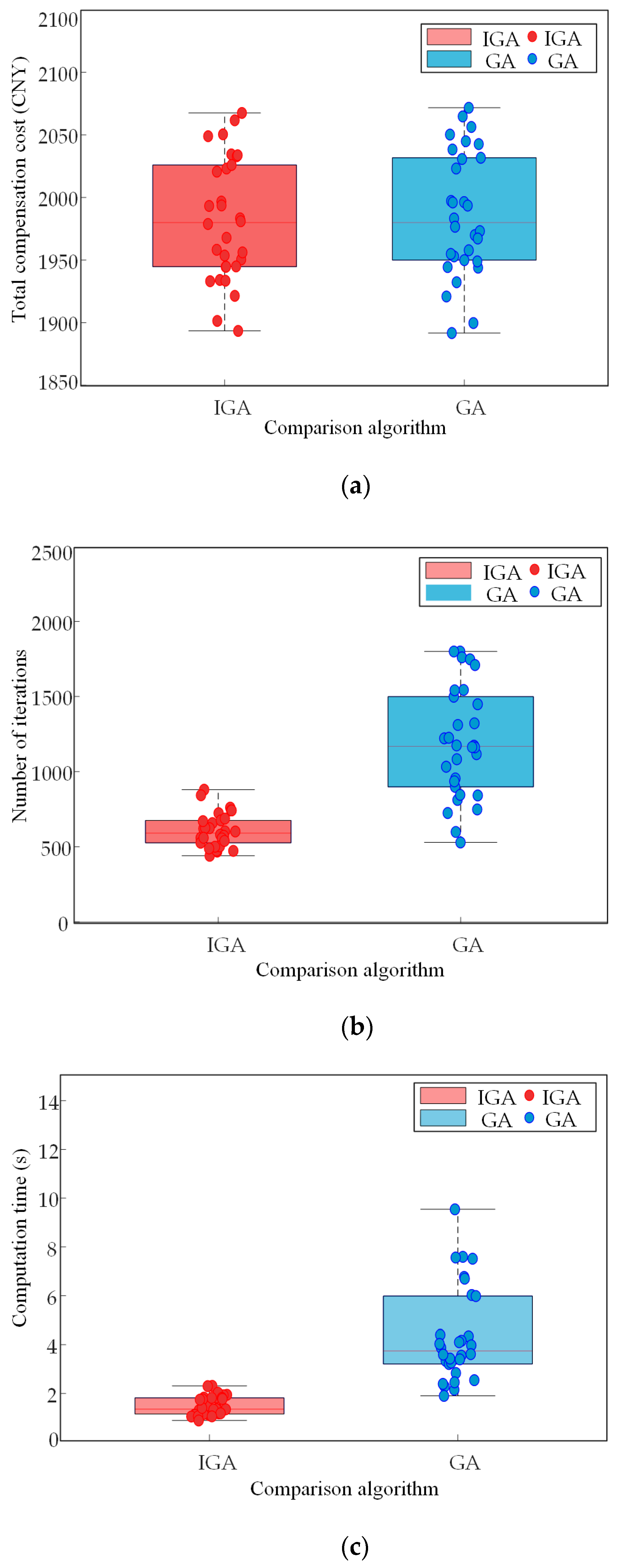

4.4. Algorithm Performance Analysis

4.4.1. Algorithm Comparison

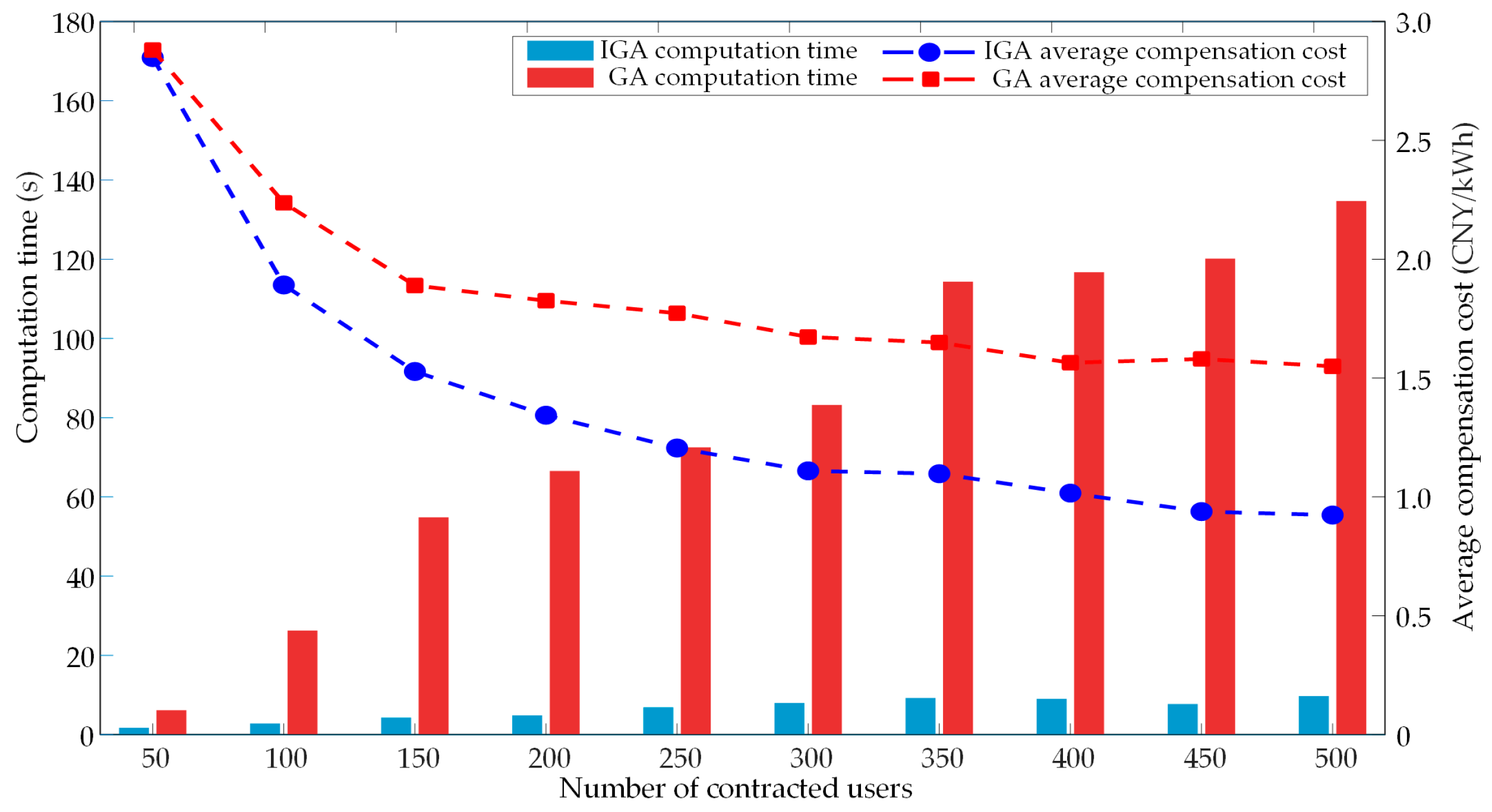

4.4.2. Applicability Analysis

4.5. Comparison with Existing Solutions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| RTDR | Real-time demand response |

| DR | Demand response |

| SoC | State-of-charge |

| UBO | Unified build-and-operate |

| EVA | Electric vehicle aggregator |

| IGA | Improved genetic algorithm |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

Appendix A

| Parameter Name | Symbol | Value | Unit |

| Total EV users | N | 70 | - |

| Contract EV users | 50 | - | |

| Non-contract EV users | 20 | - | |

| Charging efficiency | 0.95 | - | |

| Rated charging power | 7 | kW | |

| Battery capacity | Ei | 70 | kWh |

| Target SoC | 0.95 | - | |

| Initial SoC | 0.2–0.4 | - | |

| Remaining charging time | 4 | h | |

| Target load reduction | 230 | kW | |

| Incentive price | 5 | CNY/kWh | |

| Response duration | 3 | h | |

| Subsidy coefficient | 0.8 | - | |

| SoC loss compensation coefficient | B | 0.6 | - |

References

- Arthur, R.; Awopone, A.K.; Gyapong, S. Assessment of the Impact of Electric Vehicle Charging on Low Voltage Distribution System in Takoradi. Clean. Energy Syst. 2025, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Z. Control Strategies, Economic Benefits, and Challenges of Vehicle-to-Grid Applications: Recent Trends Research. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, H.K.; Gupta, N.; Agrawal, P.K.; Niazi, K.; Swarnkar, A. EV charging strategies for office parking lots to relieve local grids. Sustain. Energy, Grids Networks 2025, 44, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Bharati, G.; Chakraborty, P.; Chen, B.; Nishikawa, T.; Motter, A.E. Practical Challenges in Real-Time Demand Response. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4573–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, V.B.F.; de Doile, G.N.D.; Troiano, G.; Dias, B.H.; Bonatto, B.D.; Soares, T.; Filho, W.d.F. Electricity Markets in the Context of Distributed Energy Resources and Demand Response Programs: Main Developments and Challenges Based on a Systematic Literature Review. Energies 2022, 15, 7784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatuanramtharnghaka, B.; Deb, S.; Singh, K.R.; Ustun, T.S.; Kalam, A. Reviewing Demand Response for Energy Management with Consideration of Renewable Energy Sources and Electric Vehicles. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossary, M. Enhancing Urban Electric Vehicle (EV) Fleet Management Efficiency in Smart Cities: A Predictive Hybrid Deep Learning Framework. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 3678–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Q. A Stackelberg-based competition model for optimal participation of electric vehicle load aggregators in demand response programs. Energy 2025, 315, 134414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanelyte, D.; Radziukyniene, N.; Radziukynas, V. Overview of Demand-Response Services: A Review. Energies 2022, 15, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, S.; Qiu, J.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, J. Pricing for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations Based on the Responsiveness of Demand. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, H.; Peng, K.; Zhang, C.; Qu, X. A real-time charging price strategy of distribution network based on comprehensive demand response of EVs and cooperative game. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrucci, A.; Vallianos, C.; Buonomano, A.; Delcroix, B.; Athienitis, A. Coordinated load management of building clusters and electric vehicles charging: An economic model predictive control investigation in demand response. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 339, 119965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Liu, J.; Guo, X.; Jiang, M.; Liu, F.; Hao, H. Charging and Discharging Optimization Strategy for Electric Vehicles in Residential Community Based on User Response Portrait. Smart Power 2022, 50, 87–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Huang, L.; Liu, H. Optimization of Peak-Valley TOU Power Price Time-Period in Ordered Charging Mode of Electric Vehicle. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2012, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjana, V.S.; Reddy, Y.M.; Kumar, M.R.; Raju, B.A. Enhancing residential demand response through dynamic pricing forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2023 Second IEEE International Conference on Measurement, Instrumentation, Control and Automation (ICMICA), Kurukshetra, India, 3–5 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamaniotis, M.; Gatsis, N.; Tsoukalas, L.H. Virtual Budget: Integration of electricity load and price anticipation for load morphing in price-directed energy utilization. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2018, 158, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, P.; Wang, W.; Langner, F. Model predictive control for demand flexibility of a residential building with multiple distributed energy resources. Energy Build. 2024, 305, 113884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuelvas, J.; Ruiz, F.; Gruosso, G. A time-of-use pricing strategy for managing electric vehicle clusters. Sustain. Energy, Grids Networks 2021, 25, 100411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Wang, Y.; Xie, C.; Xiong, B.; Zhang, Q.; Huang, L. A dispatching strategy for electric vehicle aggregator combined price and incentive demand response. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2021, 3, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Londono, C.; Cordoba, A.; Vuelvas, J.; Ruiz, F. Mixed Incentive-Based and Direct Control Framework for EV Demand Response. In Proceedings of the 19th IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC 2023), Milan, Italy, 24–27 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhang, G.; Tian, C.; Peng, W.; Liu, Y. Charging Behavior Portrait of Electric Vehicle Users Based on Fuzzy C-Means Clustering Algorithm. Energies 2024, 17, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, C.; Cai, G.; Koh, L.H. Charging and discharging optimization strategy for electric vehicles considering elasticity demand response. eTransportation 2023, 18, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ma, W.; Xue, Y.; Yao, L.; Xie, D. Quantification of Reserve Capacity Provided by Electric Vehicle Aggregator Based on Framework of Cyber-Physical-Social System in Energy. Autom. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wei, X.; Zu, G.; Ma, Y.; Yu, X.; Mu, Y. The charge-discharge compensation pricing strategy of electric vehicle aggregator considering users response willingness from the perspective of Stackelberg game. IET Smart Grid 2023, 7, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponciroli, R.; Stauff, N.E.; Ramsey, J.; Ganda, F.; Vilim, R.B. An Improved Genetic Algorithm Approach to the Unit Commitment/Economic Dispatch Problem. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 4005–4013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Orderly Charging and Discharging Group Scheduling Strategy for Electric Vehicles. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Xie, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J. Electric Vehicle Aggregator Dispatching Strategy Under Price and Incentive Demand Response. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 40, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Fachrizal, R.; Munkhammar, J.; Ebel, T.; Adam, R.C. The Impact of Considering State-of-Charge-Dependent Maximum Charging Powers on the Optimal Electric Vehicle Charging Scheduling. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification 2023, 9, 4517–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| User Type | pl | ph | Proportion of Contracted Users |

|---|---|---|---|

| flexible | [0, 1] | [2, 3] | 40% |

| neutral | [1, 2] | [3, 4] | 40% |

| rigid | [2, 3] | [4, 5] | 20% |

| Symbol | Description | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| (kW) | The theoretical maximum adjustable power that all contracted users can provide during the real-time demand response (RTDR) period, while satisfying device and user constraints. | =max |

| (kW) | The actual active response power provided by contracted users under a given incentive cost level. | |

| (kW) | Response power is obtained through mandatory curtailment when active response is insufficient. | = |

| F (%) | The proportion of contracted users’ active response power to the total response power. | F= |

| (CNY) | Total grid-side incentive received by aggregator, corresponding solely to active response. | = |

| (CNY) | Total benefit of all contracted users, including power regulation compensation and state-of-charge (SoC) loss compensation. | M2: = M3: = |

| (CNY) | Net aggregator benefit, equal to grid subsidy minus total user compensation. | − |

| (CNY/kWh) | Average compensation cost per unit response power paid by the aggregator. | M2: M3: |

| Metric | Mechanism 1 | Mechanism 2 | Mechanism 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 183.02 | 236.60 | |

| 230 | 230 | 230 | |

| 0 | 183.02 | 230 | |

| 230 | 46.98 | 0 | |

| F | 0 | 79.6% | 100% |

| 0 | 2745.4 | 3450.0 | |

| 0 | 1380.2 | 1927.0 | |

| 0 | 1365.2 | 1523.0 |

| Indicators | IGA | GA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total compensation cost (CNY) | Mean value | 1982.10 | 1986.43 |

| Standard deviation | 47.92 | 49.55 | |

| Number of iterations | Mean value | 609 | 1427 |

| Standard deviation | 112 | 368 | |

| Computation time (s) | Mean value | 1.50 | 5.06 |

| Standard deviation | 0.39 | 1.96 |

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Uniform Proportional Reduction (M1) |

|

|

| Power Regulation Compensation (M2) |

|

|

| Dual-Dimensional Compensation (M3) |

|

|

| Other Methods (e.g., Refs. [21,22,23]) |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hao, S.; Zu, G. Study on a Dual-Dimensional Compensation Mechanism and Bi-Level Optimization Approach for Real-Time Electric Vehicle Demand Response in Unified Build-and-Operate Communities. World Electr. Veh. J. 2026, 17, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010004

Hao S, Zu G. Study on a Dual-Dimensional Compensation Mechanism and Bi-Level Optimization Approach for Real-Time Electric Vehicle Demand Response in Unified Build-and-Operate Communities. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2026; 17(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Shuang, and Guoqiang Zu. 2026. "Study on a Dual-Dimensional Compensation Mechanism and Bi-Level Optimization Approach for Real-Time Electric Vehicle Demand Response in Unified Build-and-Operate Communities" World Electric Vehicle Journal 17, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010004

APA StyleHao, S., & Zu, G. (2026). Study on a Dual-Dimensional Compensation Mechanism and Bi-Level Optimization Approach for Real-Time Electric Vehicle Demand Response in Unified Build-and-Operate Communities. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 17(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010004