Digital Twin Empowers Electric Vehicle Supply Chain Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To our knowledge, this is the first study to explicitly investigate the impact of digital twins on enhancing the resilience of electric vehicle supply chains. It integrates digital twin and supply chain resilience into a unified analytical framework, providing novel perspectives and a methodological approach for supply chain resilience research.

- (2)

- This study empirically explores the complex mechanisms through which digital twin empowers the resilience of electric vehicle supply chains, addressing gaps in existing research regarding the underlying mechanisms of this empowerment. It also proposes corresponding recommendations, offering valuable insights for enterprises seeking to enhance supply chain resilience.

- (3)

- This study employs the dynamic fsQCA method in the field of supply chain resilience, enriching the research methodology in this domain.

2. Theoretical Foundation

2.1. Intelligent Supply Chain Theory

2.2. Complex Adaptive Systems Theory

2.3. Dynamic Capability Theory

3. Intelligent Digital Twin System for Electric Vehicle Supply Chains

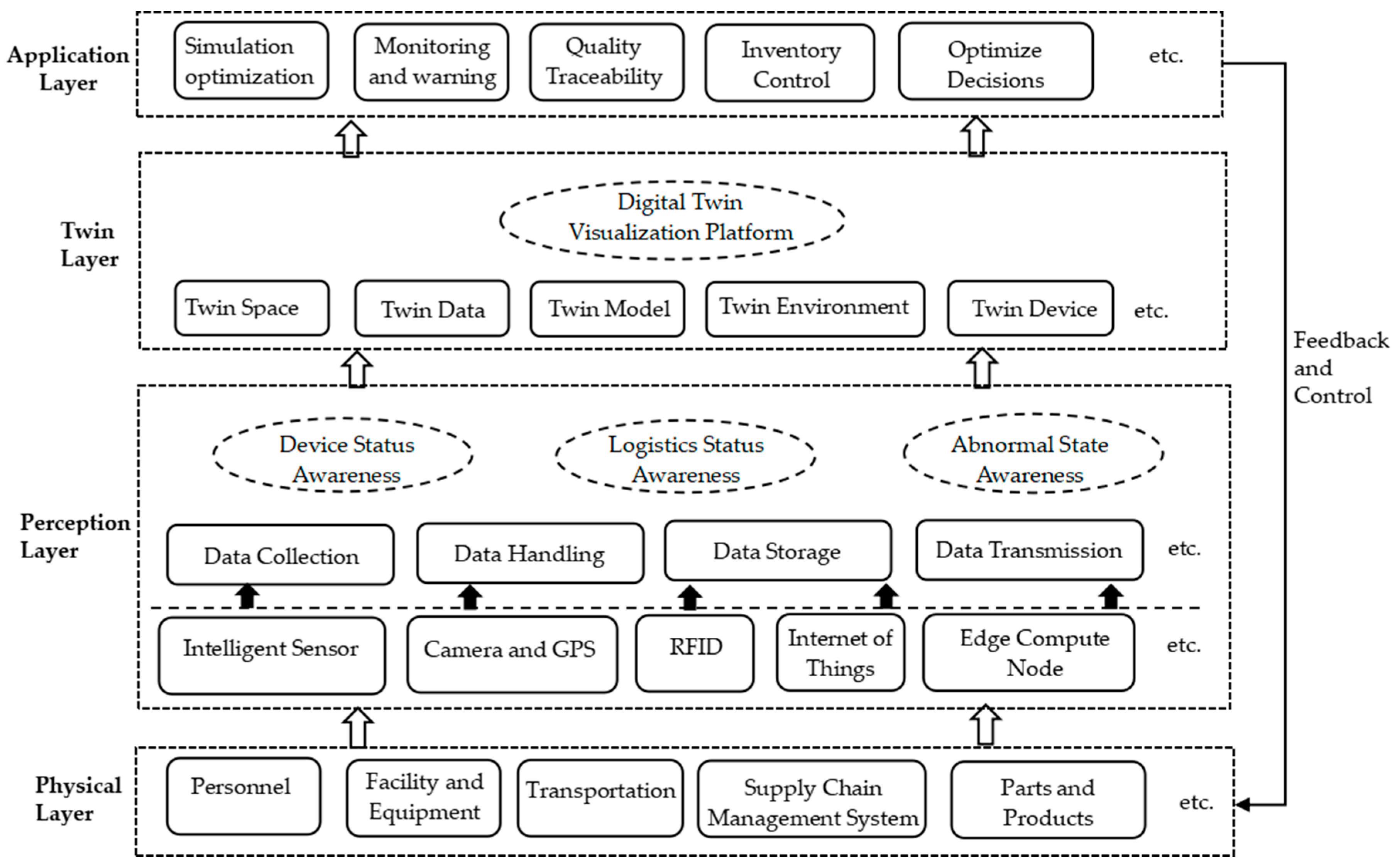

3.1. Hierarchical Architecture of an Intelligent Digital Twin System for the Electric Vehicle Supply Chain

- (1)

- The physical layer represents the collection of physical entities within the supply chain of electric vehicle enterprises, encompassing physical elements such as personnel, facilities, and equipment;

- (2)

- The perception layer collects, processes, stores, and transmits data through sensor devices, GPS positioning, and other equipment, digitally mapping logistics and abnormal conditions in the physical space;

- (3)

- The digital twin layer is built upon a digital twin platform, representing virtual counterparts of physical scenarios, including twin models;

- (4)

- The application layer refers to services provided throughout the entire supply chain life cycle from raw materials and components to vehicle manufacturing, maintenance, and recycling—encompassing monitoring and early warning systems, simulation optimization, and so on.

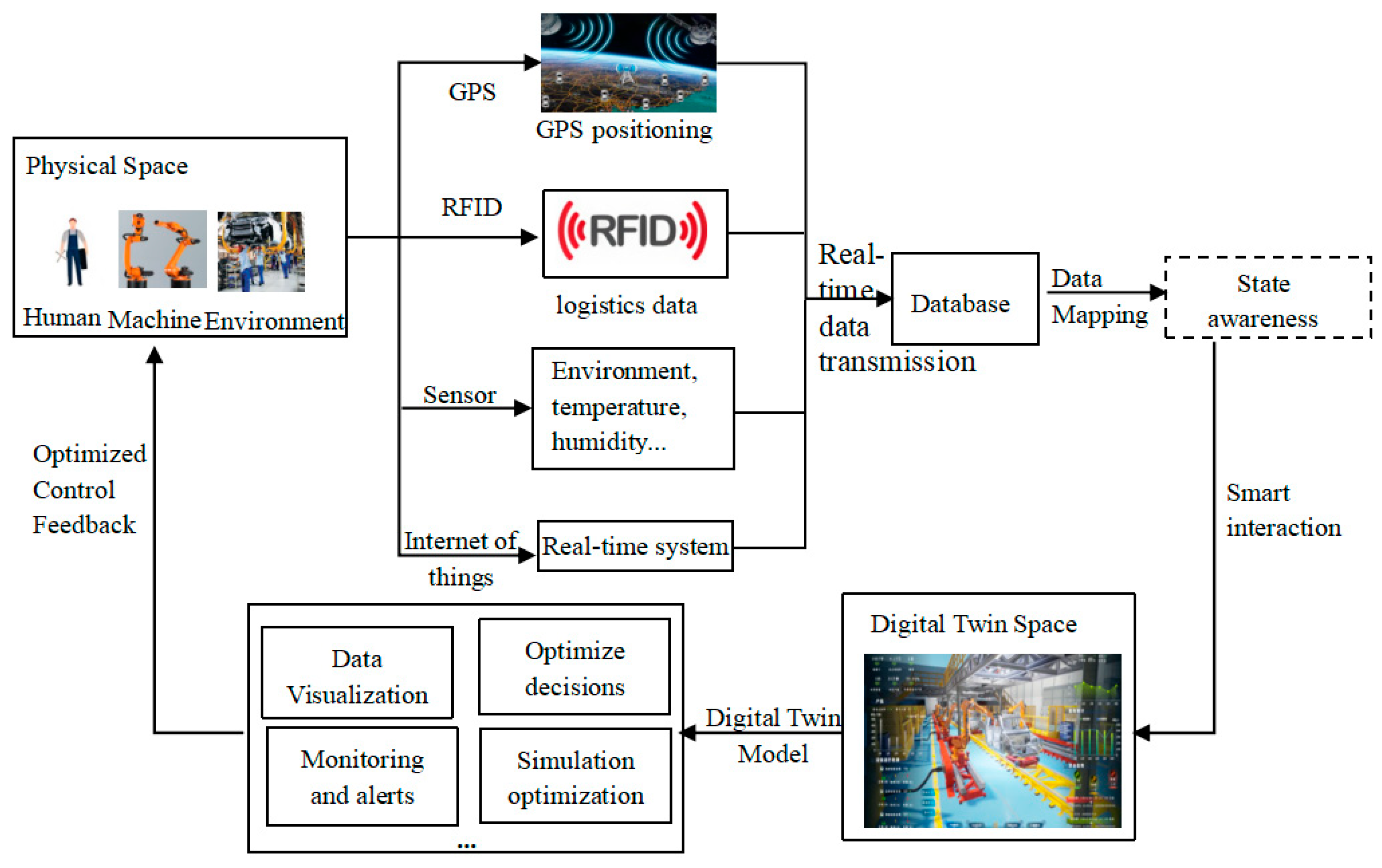

3.2. Operational Mechanism of the Intelligent Digital Twin System for the Electric Vehicle Supply Chain

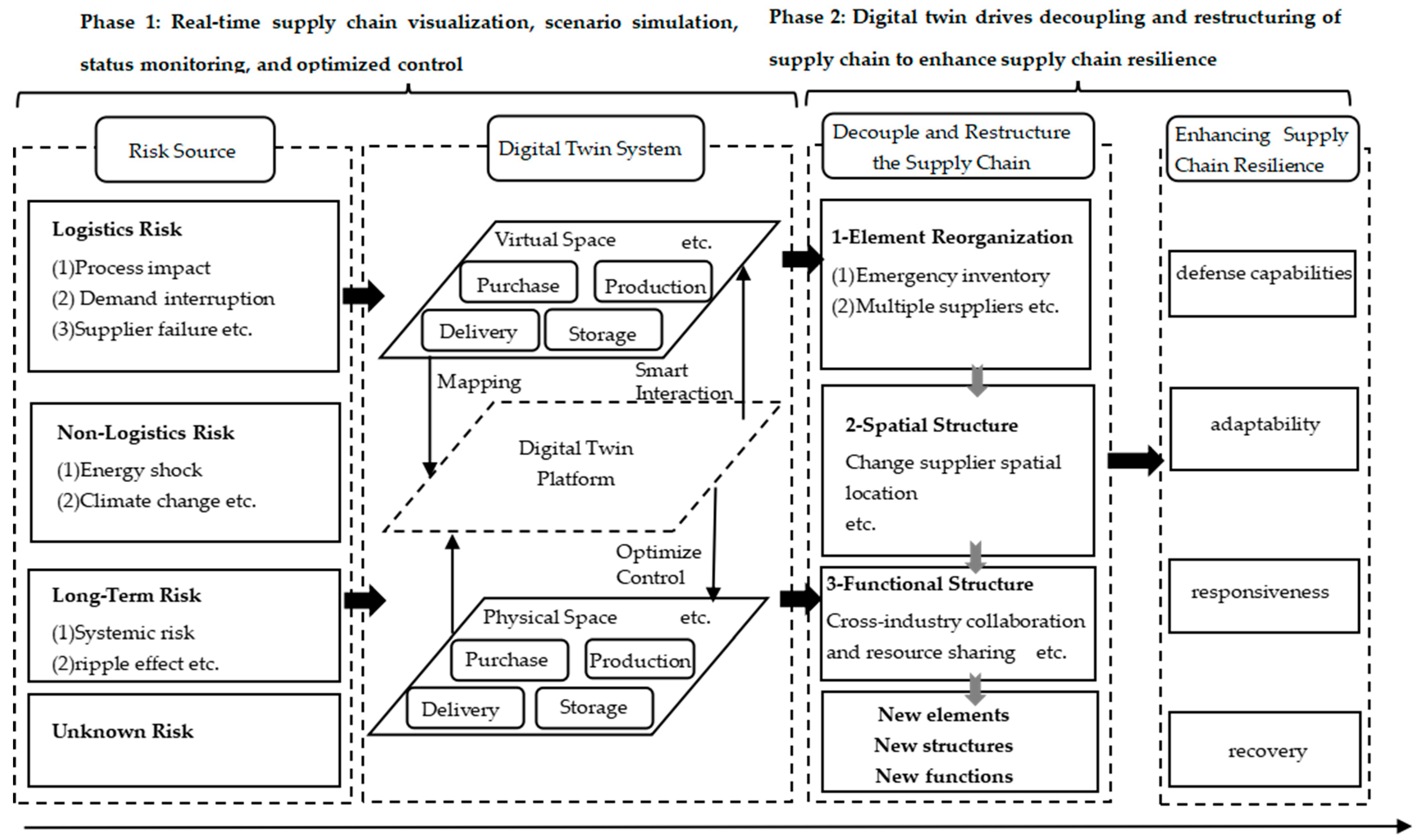

3.3. The Mechanism of Digital Twin Empowering Resilience Enhancement in the Electric Vehicle Supply Chain

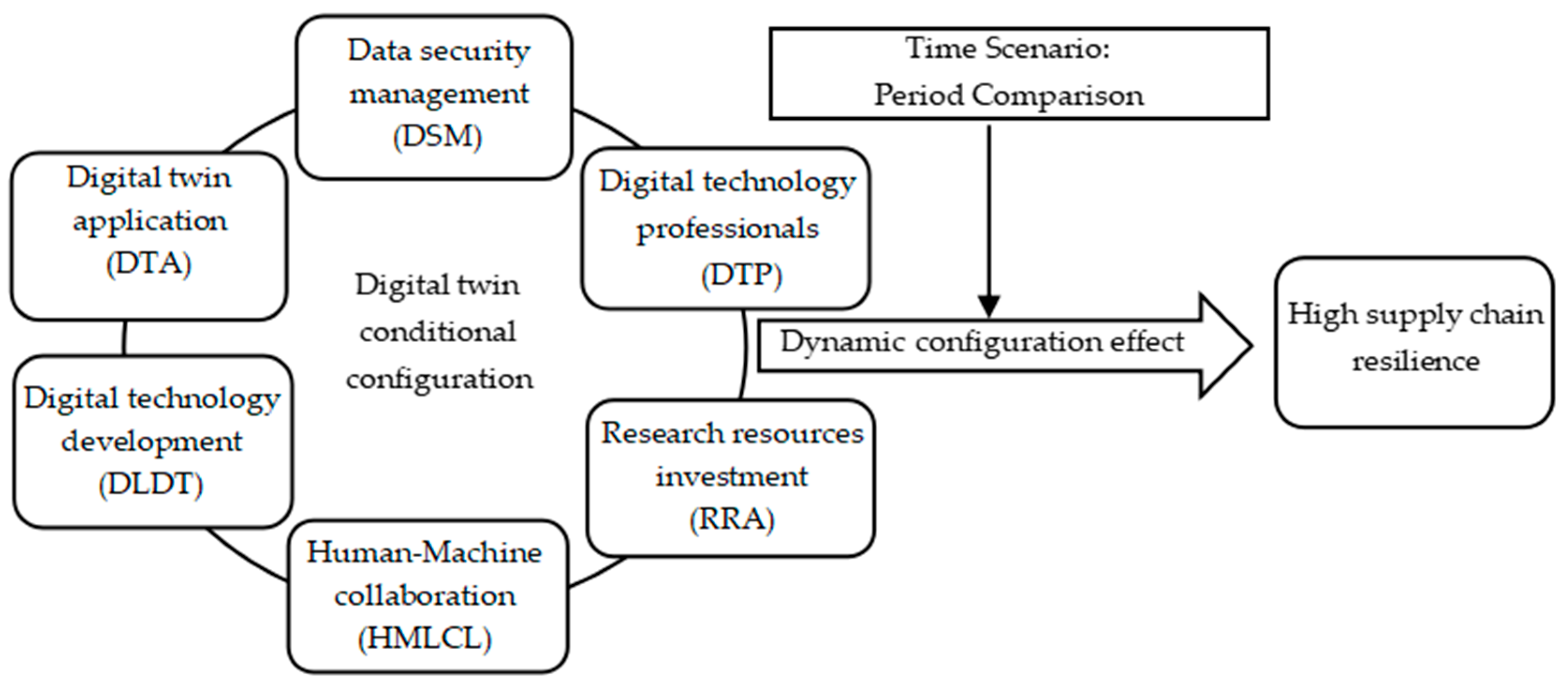

3.4. Analysis and Integration Between Architecture, Operational Mechanisms, and Variable Dimensions

4. Research Methods and Design

4.1. Research Methods

4.2. Detailed Procedures for Dynamic fsQCA

4.2.1. Data Calibration and Dynamic Setting

4.2.2. Necessity Analysis and Truth Table Construction

4.2.3. Condition Configuration Identification and Organized Analysis

4.2.4. Robustness Test Process

4.3. Sample Selection and Data Sources

4.4. Variable Measurement and Calibration

4.4.1. Antecedent Variables Measurement

4.4.2. Outcome Variables Measurement

- (1)

- Defense Capability. Drawing upon the research of Fan et al. [24] and Shareef et al. [25], this study employed supply chain visibility and risk prevention mechanisms as measurement indicators. Based on the fsQCA variable assignment criteria, a four-value fuzzy set assignment was applied, assigning values of 0, 0.33, 0.67, and 1 to represent complete non-affiliation, partial non-affiliation, partial affiliation, and complete affiliation, respectively.

- (2)

- Responsiveness. Inventory turnover rate (times) was used as the metric.

- (3)

- Recovery. Financial strength influences the speed of recovery and adjustment capabilities within an enterprise’s supply chain. Drawing upon the research of Zhang et al. [26], two metrics, return on assets and debt-paying capacity, were employed to measure recovery. Return on assets was measured by the ratio of net profit to average total assets. Debt-paying capacity is expressed as the ratio of net cash flow from operating activities to current liabilities.

4.4.3. Variables Calibration

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Necessity Analysis of a Single Condition

5.2. Configuration Analysis

5.2.1. Configuration of Conditions for Achieving High Supply Chain Resilience

- (1)

- Configuration Analysis for 2020

- (2)

- Configuration Analysis for 2022

- (3)

- Configuration Analysis for 2024

- (4)

- Analysis of Multi-period Configuration Evolution

5.2.2. Configuration of Conditions for Achieving Non-High Supply Chain Resilience

5.3. Robustness Test

6. Discussion and Conclusions

7. Managerial Implications

- (1)

- For Electric Vehicle Enterprise Managers: Selecting Suitable Configuration Paths

- (2)

- For Relevant Government Departments: Provide Support and Formulate Policies

- (3)

- For Electric Vehicle Industry: Address the Risks of Emerging Technologies

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Digital Twin Core | Digital twin, Virtual Twin, Digital Shadow, Simulation, Real-time Modeling, Data-driven Model, 3D Modeling, Cyber-Physical Systems |

| Digital Infrastructure &Algorithm | IoT & Internet of Things, Big Data Analytics, Artificial Intelligence & AI, Machine Learning, Cloud Computing, Edge Computing, Sensor Technology, Digital Platform, Cloud Technologies |

| Smart Manufacturing & Mobility | Vehicle-to-Everything, Intelligent Cockpit Simulation, Remote Diagnostics, Industry 4.0, Industry 5.0, Digital Factory & Smart Factory, Automation, Autonomous Driving & Automated Driving, Self-Driving, Intelligent Driving, Human–Machine Interaction, Robotics & Robots |

| General | Digital technology, Digitalization, Intellectualization |

References

- Brandon-Jones, E.; Squire, B.; Autry, C.W.; Petersen, K.J. A contingent resource-based perspective of supply chain resilience and robustness. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, S.; Hohenstein, N.-O.; Hartmann, E. Linking entrepreneurial orientation and supply chain resilience to strengthen business performance: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Man. 2023, 43, 1357–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proselkov, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, L.; Hofmann, E.; Choi, T.Y.; Rogers, D.; Brintrup, A. Financial Ripple Effect in Complex Adaptive Supply Networks: An Agent-Based Model. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 823–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.M.; Tong, L.; Dong, C.R.; Xin, C.H. Research on the Impact of Smart Supply Chain Policies on Enterprise Resilience: From the Perspective of Strategic Synergy Empowerment. World Econ. Stud. 2025, 7, 105–119+137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wu, M.; Kang, J.; Yu, R. D-Tracking: Digital Twin Enabled Trajectory Tracking System of Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 16457–16469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, P.K.; Soundarya, T.; Jithin, K.V. Driving sustainability-The role of digital twin in enhancing battery performance for electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2024, 604, 234464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Tan, C.; Oh, S.C.; Arinez, J.; Chang, Q. Machine learning-enhanced digital twins for predictive analytics in battery pack assembly. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, F.; Gil, S.; Barbu, C.; Cetkin, E.; Yarimca, G.; Jensen, A.C.; Larsen, P.G.; Gomes, C. Digital twin of electric vehicle battery systems: Comprehensive review of the use cases, requirements, and platforms. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 179, 113280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Huang, H. Uncertainty Shock, Digital Technology Innovation and Supply Chain Resilience. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2024, 28, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Liu, S.S. The Resilience of Enterprise Supply Chain Empowered by Data Elements: Theoretical Mechanism and Empirical Test. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy. 2025, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Song, G.; Song, S.; Huang, N.; Cheng, T. How do talent and technology factors affect supply chain robustness and resilience? Evidence from Chinese manufacturers. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2025, 125, 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.Q.; Yang, H.; Chen, G.X. Impact and Mechanism of the Digital Economy on the Resilience of Enterprise Supply Chains: From Changes in the Number of Enterprise Suppliers. Econ. Rev. J. 2024, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qu, J. Study on the Effect and Regional Differentiation of Food Supply Chain Resilience Empowered by Digital Economy. J. Northwest Minzu Univ. 2024, 01, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H. Transitioning from Digitization to Intelligent Digitization: Transition Path and Capability Building of Supply Chain. China Bus. Mark. 2025, 39, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.Y.; Dooley, K.J.; Rungtusanatham, M. Supply networks and complex adaptive systems: Control versus emergence. J. Oper. Manag. 2001, 19, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Wen, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. Intelligent optimization method of ‘human machine-environment’ integrated industrial digital twin system. Comput. Integr. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 30, 1551–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kou, H.N.; Zhang, X.H.; Wei, S.R.; Yang, Z.W.; Zhao, Y.J. Virtual physical interaction control method for intelligent cantilever road header driven by digital twin. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2025, 54, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.P.; Shi, L.Y.; Wu, Y.Q. Study on Influencing Factors and Improvement Path of Government Data Opening Service Quality—Based on the Combined Meta-fsQCA Analysis. J. Mod. Inf. 2025, 45, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.Y.; Lai, Z.L. The Impact of Supply Chain Finance on Corporate Resilience: A Resource Acquisition Perspective. Commer. Res. J. 2025, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarov, S.Y.; Holcomb, M.C. Understanding the concept of supply chain resilience. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Yuan, H.; Du, G.; Zhang, M. A demand-based three-stage seismic resilience assessment and multi-objective optimization method of community water distribution networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safe. 2024, 250, 110279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.Z.; Zhang, L.L. Research on Evaluation and Early Warning of Supply Chain Resilience Based on Improved Gray Forecasting Model. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2022, 41, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.M.; Lu, M.Y. Influencing Factors and Evaluation of Auto Companies’ Supply Chain Resilience Under the COVID-19. J. Ind. Technol. Econ. 2020, 41, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shareef, M.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kumar, V.; Hughes, D.L.; Raman, R. Sustainable supply chain for disaster management: Structural dynamics and disruptive risks. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 319, 1451–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Li, Z.M. The Impact of New Production Factors on the Resilience of ICT Manufacturing Supply Chain. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy. 2025, 42, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhou, Z.C. The influence path of Industry 4.0 technology on the integration of logistics and manufacturing industries: Based on the typical cases of NDRC. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 2025, 45, 2245–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Jia, L.D. Configuration perspective and Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): A new way of management research. J. Manag. World. 2017, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.T.; Zhang, S.D.; Zhao, Y.H. What does determine performance of government public health governance? A study on co-movement effect based on QCA. J. Manag. World. 2021, 37, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.Z.; Liu, Q.C.; Chen, K.W.; Xiao, R.Q.; Li, S.S. Ecosystem of Doing Business, Total Factor Productivity and Multiple Patterns of High-quality Development of Chinese Cities: A Configuration Analysis Based on Complex Systems View. J. Manag. World. 2022, 38, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Du, Y. The Effect of Generative AI Ethics on Users’ Continuous Usage Intentions: A PLS-SEM and fsQCA Approach. Int. J. Hum-Comput. Int. 2025, 41, 12831–12842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiss, P.C. Building better causal theories: A fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 393–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldkirch, M.; Kammerlander, N.; Wiedeler, C. Configurations for corporate venture innovation: Investigating the role of the dominant coalition. J. Bus. Ventur. 2021, 36, 106137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Assignment Standard | Assignment |

|---|---|---|

| DTA | Conducting in-depth digital twin simulation and closed-loop optimization within the supply chain | 1 |

| There are clear technical applications and projects, but their depth is limited | 0.67 | |

| Preliminary digital twin applications | 0.33 | |

| Not involved at all | 0 | |

| HMLCL | Deployed human–machine intelligent interaction within the supply chain to realize data-driven collaborative decision-making processes | 1 |

| Provide visual data dashboards, mobile management systems, or decision support tools for the electric vehicle supply chain | 0.67 | |

| Preliminary human–machine interaction collaboration | 0.33 | |

| Not involved at all | 0 | |

| DSM | Possesses a comprehensive data security management system | 1 |

| A relatively clear data security management system and technical measures have been established | 0.67 | |

| Foundational data security management system | 0.33 | |

| Not involved at all | 0 |

| Variables | 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | IP | CNA | CA | IP | CNA | CA | IP | CNA | |

| DLDT | 4.013 | 3.091 | 0.901 | 4.074 | 3.135 | 1.710 | 4.504 | 3.526 | 1.664 |

| RRA | 0.258 | 0.047 | 0.017 | 0.181 | 0.050 | 0.019 | 0.186 | 0.049 | 0.035 |

| DTP | 0.389 | 0.157 | 0.059 | 0.344 | 0.162 | 0.058 | 0.346 | 0.176 | 0.098 |

| SCR | 0.277 | 0.141 | 0.093 | 0.297 | 0.168 | 0.079 | 0.325 | 0.210 | 0.081 |

| Condition Variable | High Supply Chain Resilience | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | ||||

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| DTA | 0.721 | 0.804 | 0.922 | 0.817 | 0.770 | 0.843 |

| ~DTA | 0.559 | 0.505 | 0.425 | 0.430 | 0.475 | 0.496 |

| DLDT | 0.723 | 0.730 | 0.798 | 0.663 | 0.779 | 0.818 |

| ~DLDT | 0.603 | 0.594 | 0.482 | 0.527 | 0.511 | 0.556 |

| HMLCL | 0.596 | 0.775 | 0.649 | 0.757 | 0.675 | 0.891 |

| ~HMLCL | 0.672 | 0.543 | 0.615 | 0.488 | 0.591 | 0.531 |

| RRA | 0.588 | 0.638 | 0.610 | 0.597 | 0.627 | 0.740 |

| ~RRA | 0.676 | 0.625 | 0.674 | 0.616 | 0.643 | 0.628 |

| DTP | 0.609 | 0.630 | 0.624 | 0.596 | 0.671 | 0.736 |

| ~DTP | 0.699 | 0.673 | 0.696 | 0.650 | 0.624 | 0.650 |

| DSM | 0.779 | 0.705 | 0.688 | 0.827 | 0.808 | 0.880 |

| ~DSM | 0.468 | 0.520 | 0.669 | 0.520 | 0.524 | 0.550 |

| Condition Variable | Non-High Supply Chain Resilience | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | ||||

| Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | Consistency | Coverage | |

| DTA | 0.453 | 0.508 | 0.495 | 0.491 | 0.446 | 0.425 |

| ~DTA | 0.825 | 0.748 | 0.816 | 0.921 | 0.836 | 0.760 |

| DLDT | 0.590 | 0.599 | 0.612 | 0.569 | 0.532 | 0.487 |

| ~DLDT | 0.734 | 0.727 | 0.638 | 0.779 | 0.801 | 0.760 |

| HMLCL | 0.438 | 0.573 | 0.423 | 0.551 | 0.400 | 0.460 |

| ~HMLCL | 0.828 | 0.673 | 0.814 | 0.722 | 0.905 | 0.708 |

| RRA | 0.596 | 0.649 | 0.624 | 0.682 | 0.563 | 0.579 |

| ~RRA | 0.667 | 0.619 | 0.631 | 0.644 | 0.747 | 0.636 |

| DTP | 0.662 | 0.689 | 0.664 | 0.710 | 0.614 | 0.587 |

| ~DTP | 0.645 | 0.623 | 0.622 | 0.649 | 0.724 | 0.657 |

| DSM | 0.570 | 0.518 | 0.448 | 0.602 | 0.507 | 0.482 |

| ~DSM | 0.675 | 0.754 | 0.871 | 0.758 | 0.874 | 0.798 |

| Condition Variable | 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | B1 | B2 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

| DTA | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ● | ● | ⬤ | ⬤ | ||

| DLDT | ● | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ⬤ | ⬤ | |||

| HMLCL | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ||||

| RRA | ● | ● | ● | ⬤ | ||||||

| DTP | ● | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | ||||

| DSM | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ● | ⬤ | ||

| Consistency | 0.862 | 0.895 | 0.892 | 0.959 | 0.953 | 0.960 | 0.982 | 0.949 | 0.996 | 0.953 |

| Raw coverage | 0.357 | 0.247 | 0.366 | 0.206 | 0.304 | 0.359 | 0.302 | 0.294 | 0.378 | 0.337 |

| Unique coverage | 0.081 | 0.002 | 0.118 | 0.016 | 0.072 | 0.127 | 0.0001 | 0.016 | 0.062 | 0.044 |

| Total consistency | 0.829 | 0.967 | 0.946 | |||||||

| Total coverage | 0.545 | 0.431 | 0.552 | |||||||

| Configuration Type | 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | Trajectory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dual-driven by twin and safety | √ | √ | Turning trajectory | |

| comprehensive upgrade digital twin | √ | Turning trajectory | ||

| human–machine safety-driven | √ | √ | Turning trajectory | |

| human–machine interaction dominant | √ | Turning trajectory | ||

| advanced interactive digital twin environment | √ | Turning trajectory | ||

| four-dimensional driven digital twin | √ | Turning trajectory |

| Condition Variable | 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA1 | NA2 | NA3 | NB1 | NB2 | NB3 | NB4 | NC1 | NC2 | |

| DTA | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ||

| DLDT | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⬤ | ⊗ | |||||

| HMLCL | ⬤ | ||||||||

| RRA | ⬤ | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ||||

| DTP | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| DSM | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | ⊗ | |||||

| Consistency | 0.945 | 0.928 | 0.954 | 0.948 | 0.960 | 0.962 | 0.962 | 0.934 | 0.922 |

| Raw coverage | 0.414 | 0.286 | 0.215 | 0.546 | 0.496 | 0.415 | 0.375 | 0.617 | 0.687 |

| Unique coverage | 0.171 | 0.033 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.033 | 0.027 | 0.032 | 0.049 | 0.119 |

| Total consistency | 0.946 | 0.956 | 0.921 | ||||||

| Total coverage | 0.521 | 0.683 | 0.736 | ||||||

| Condition Variable | 2020 | 2022 | 2024 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | B1 | B2 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | |

| DTA | ⬤ | ● | ● | ● | ● | ⬤ | ⬤ | |||

| DLDT | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ⬤ | ⬤ | |||

| HMLCL | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | |||||

| RRA | ● | ⬤ | ● | ● | ⬤ | |||||

| DTP | ⊗ | ⊗ | ● | ● | ● | ⊗ | ⊗ | |||

| DSM | ● | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ⬤ | ● | ⬤ | |||

| Consistency | 0.817 | 0.863 | 0.871 | 0.876 | 0.887 | 0.901 | 0.963 | 0.927 | 0.998 | 0.942 |

| Raw coverage | 0.296 | 0.344 | 0.154 | 0.112 | 0.242 | 0.255 | 0.258 | 0.266 | 0.317 | 0.271 |

| Unique coverage | 0.139 | 0.134 | 0.041 | 0.010 | 0.088 | 0.100 | 0.001 | 0.034 | 0.058 | 0.036 |

| Total consistency | 0.813 | 0.917 | 0.934 | |||||||

| Total coverage | 0.562 | 0.342 | 0.525 | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, M. Digital Twin Empowers Electric Vehicle Supply Chain Resilience. World Electr. Veh. J. 2026, 17, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010013

Zhou X, Wang X, Zhu M. Digital Twin Empowers Electric Vehicle Supply Chain Resilience. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2026; 17(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Xiaoye, Xuan Wang, and Meilin Zhu. 2026. "Digital Twin Empowers Electric Vehicle Supply Chain Resilience" World Electric Vehicle Journal 17, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010013

APA StyleZhou, X., Wang, X., & Zhu, M. (2026). Digital Twin Empowers Electric Vehicle Supply Chain Resilience. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 17(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010013