A Hybrid Lagrangian Relaxation and Adaptive Sheep Flock Optimization to Assess the Impact of EV Penetration on Cost

Abstract

1. Introduction

- This work proposes a novel hybrid optimization framework combining LR and ASFO to address the complex problem of the impact of FCS on scheduling the MG resources and on total cost, that systematically integrates operational constraints such as power balance, voltage limits, and capacity bounds into the LR framework, while ASFO efficiently handles the non-linearities and high-dimensional nature of the search space.

- An adaptive penalty-handling mechanism is embedded within ASFO to ensure constraint feasibility during the search process, improving the robustness of the solution under practical conditions.

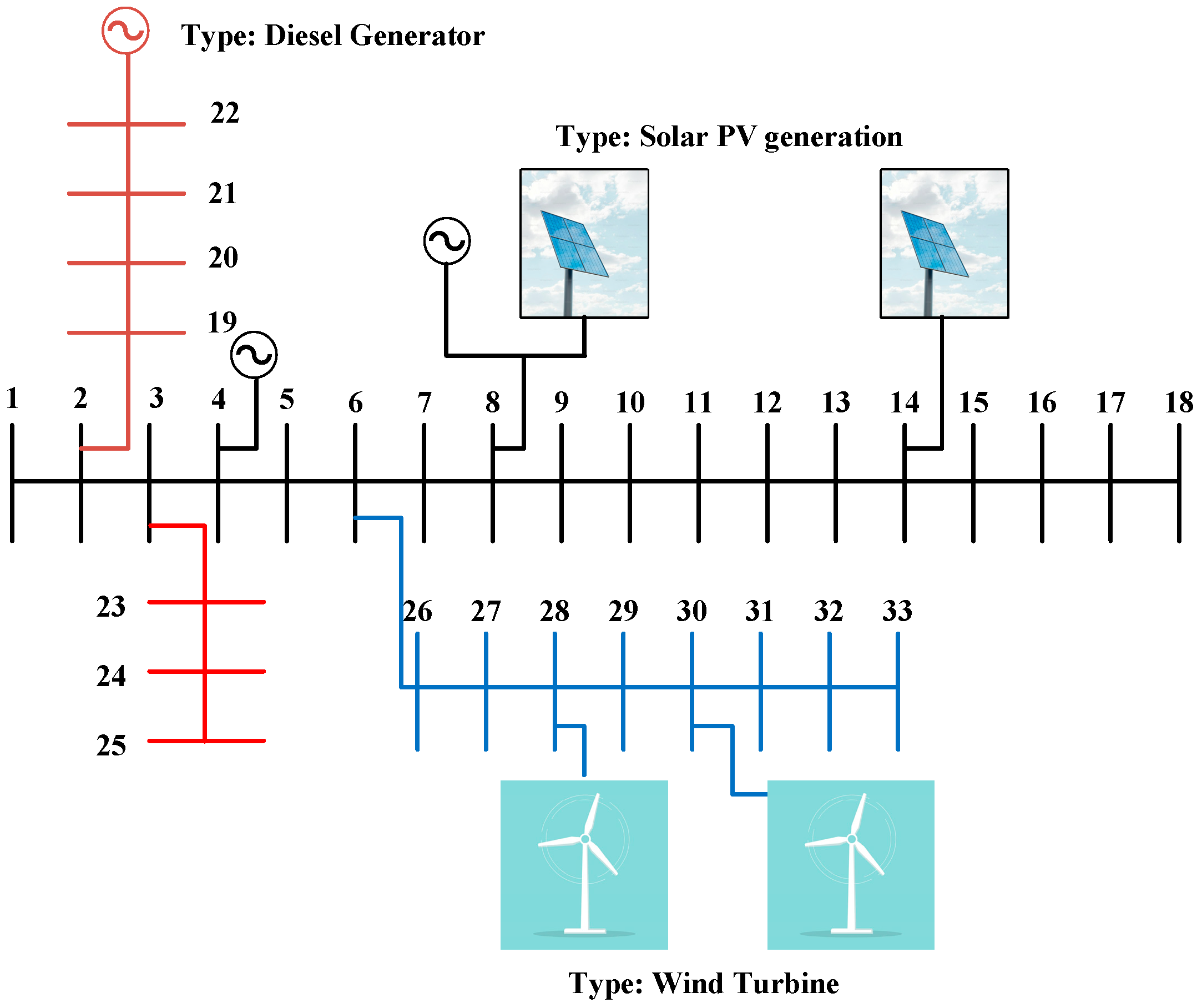

- The proposed framework is tested on a standard IEEE 33-bus test system and designed to be scalable and generalizable to future smart grid deployments with high EV and DER penetration.

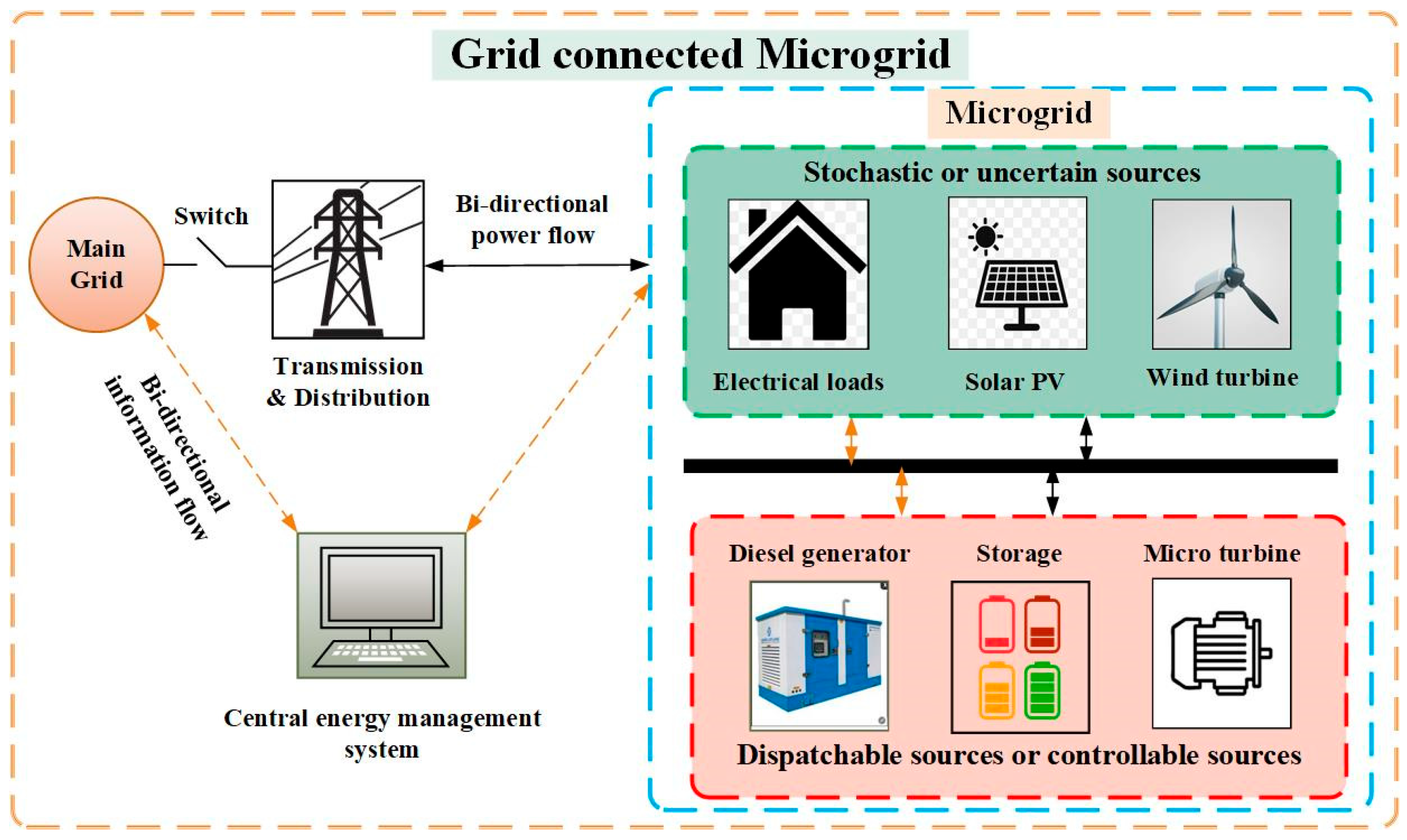

2. Microgrid Modeling

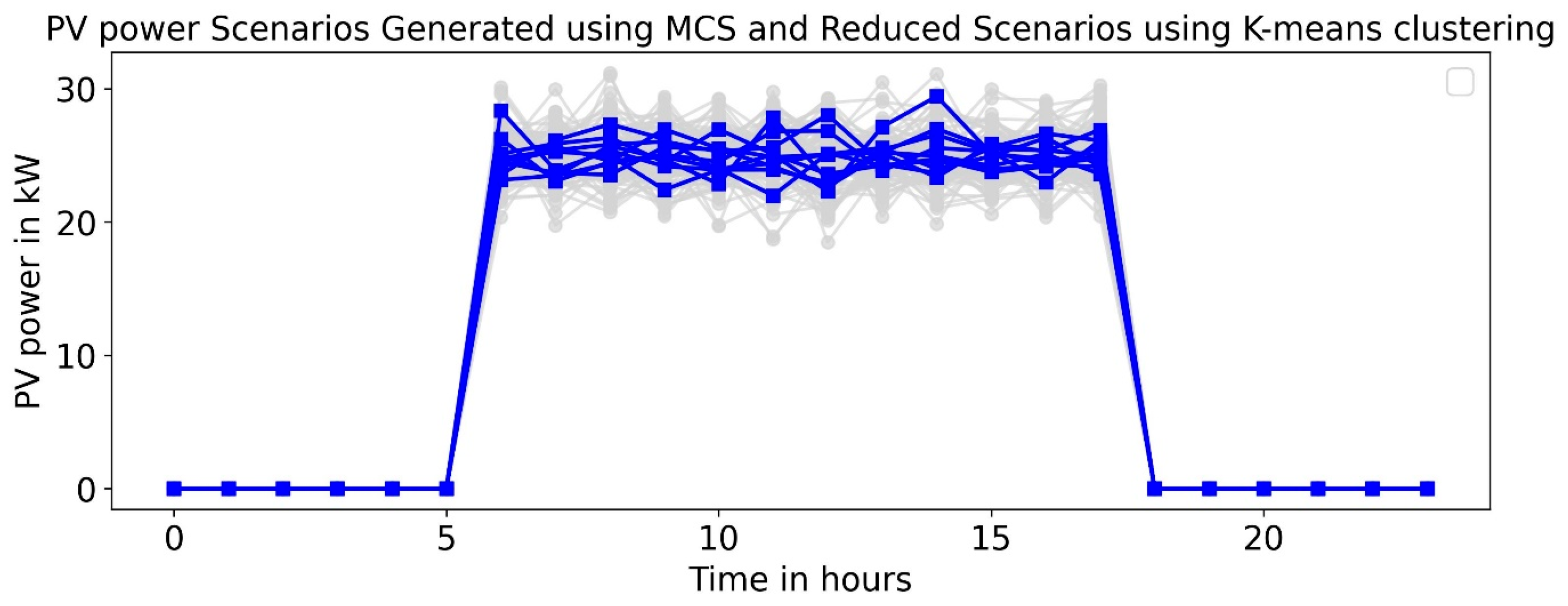

2.1. Photovoltaic System

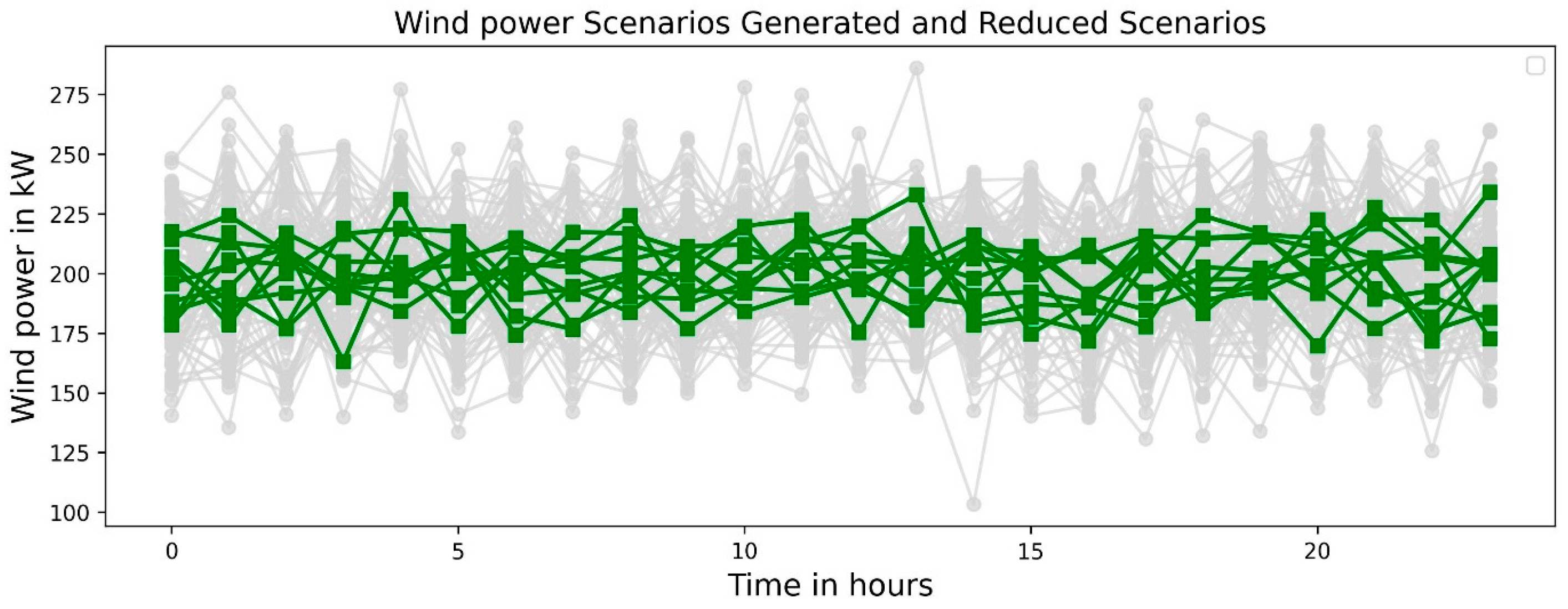

2.2. Wind Turbine (WT)

2.3. Diesel Generator

2.4. Fuel Cell

2.5. Microturbine

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Power Balance Constraint

3.2. Inequality Constraints

3.3. BESS Constraints

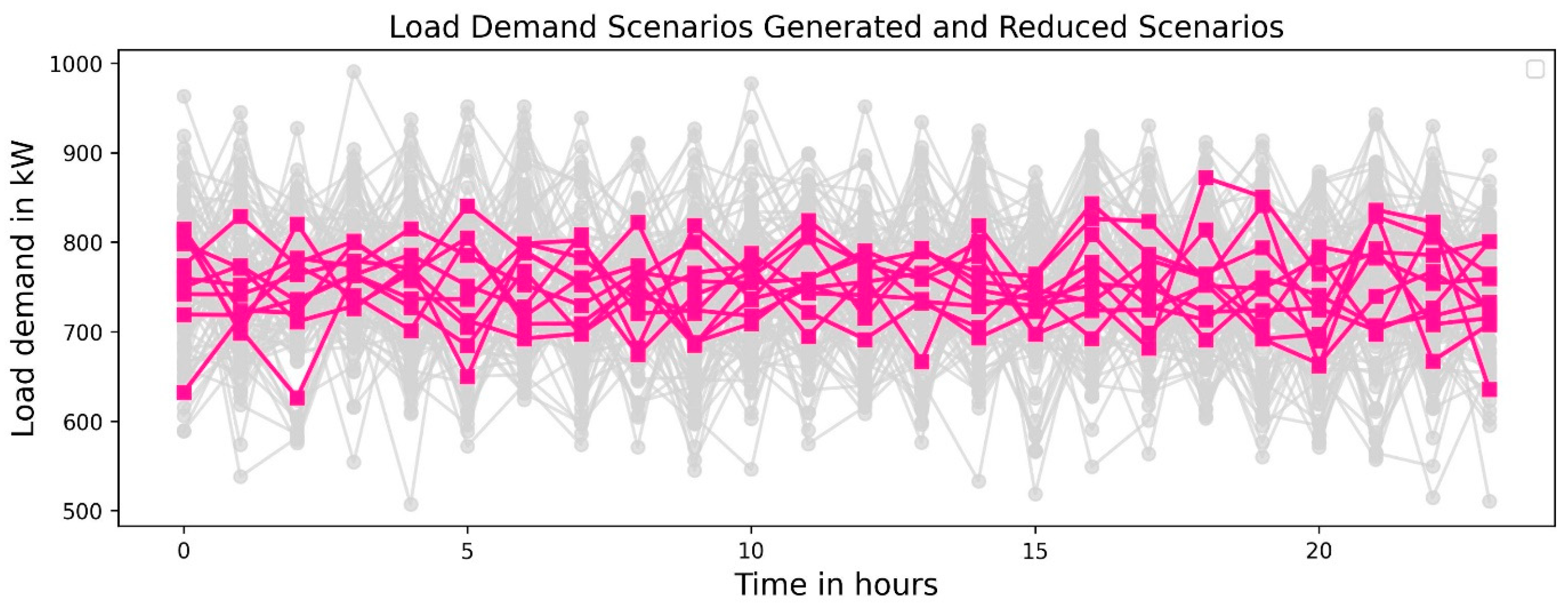

- Modeling load uncertainty: A Normal distribution was employed to model the uncertainties in the load demand. Load uncertainty is modeled using a Normal (Gaussian) distribution because aggregated demand in distribution networks naturally exhibits Gaussian characteristics. A feeder’s total load is the sum of a large number of independent or weakly correlated consumer behaviors; the aggregation of many such random variables tends to follow a normal distribution, regardless of the individual load patterns [39].

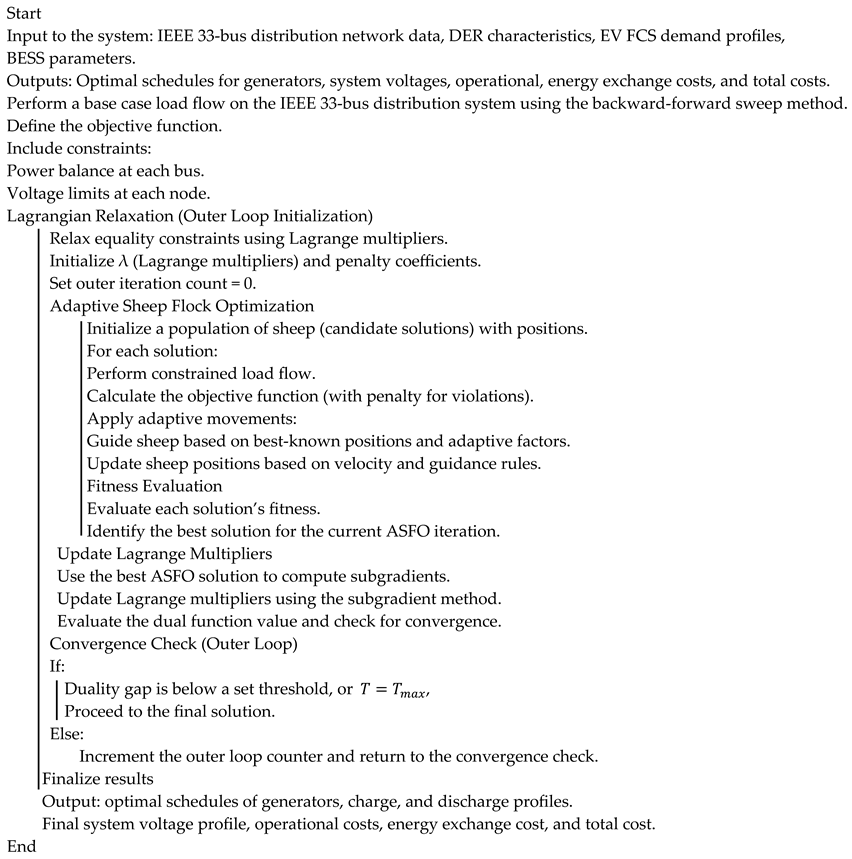

4. Proposed Methodology

4.1. Lagrangian Relaxation

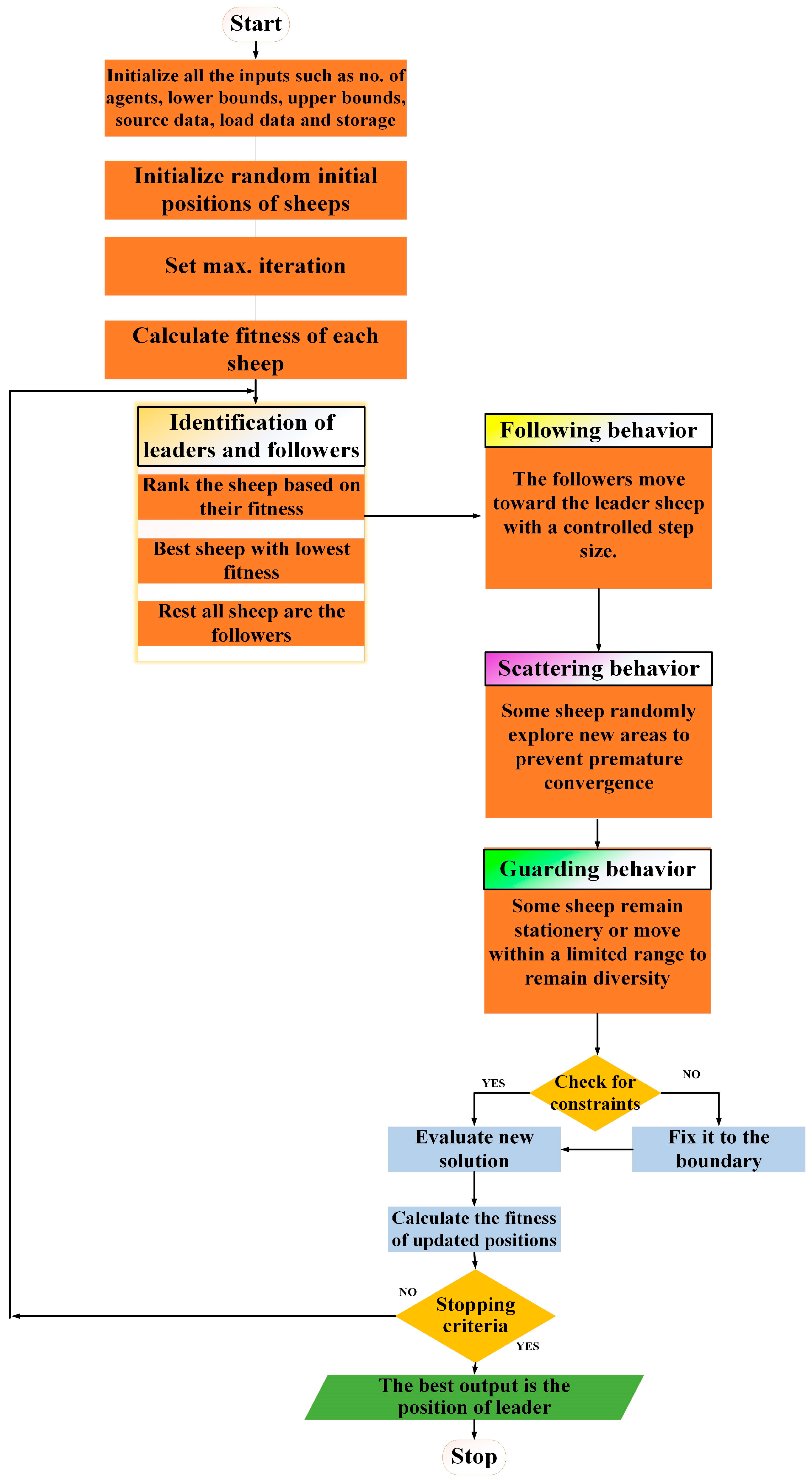

4.2. Sheep Flock Optimization

4.2.1. Limitations of SFO

4.2.2. Adaptive SFO

| Algorithm 1. Proposed algorithm for energy management. Proposed hybrid LR and ASFO |

|

5. Results & Discussion

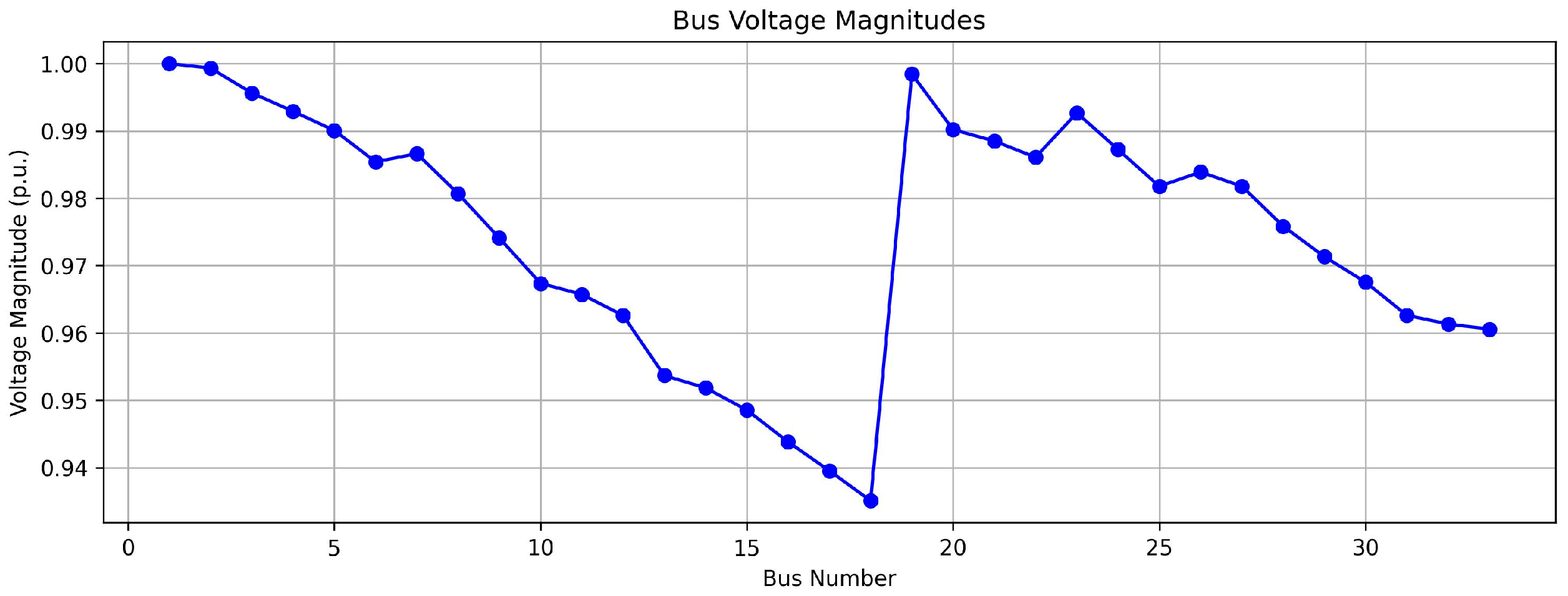

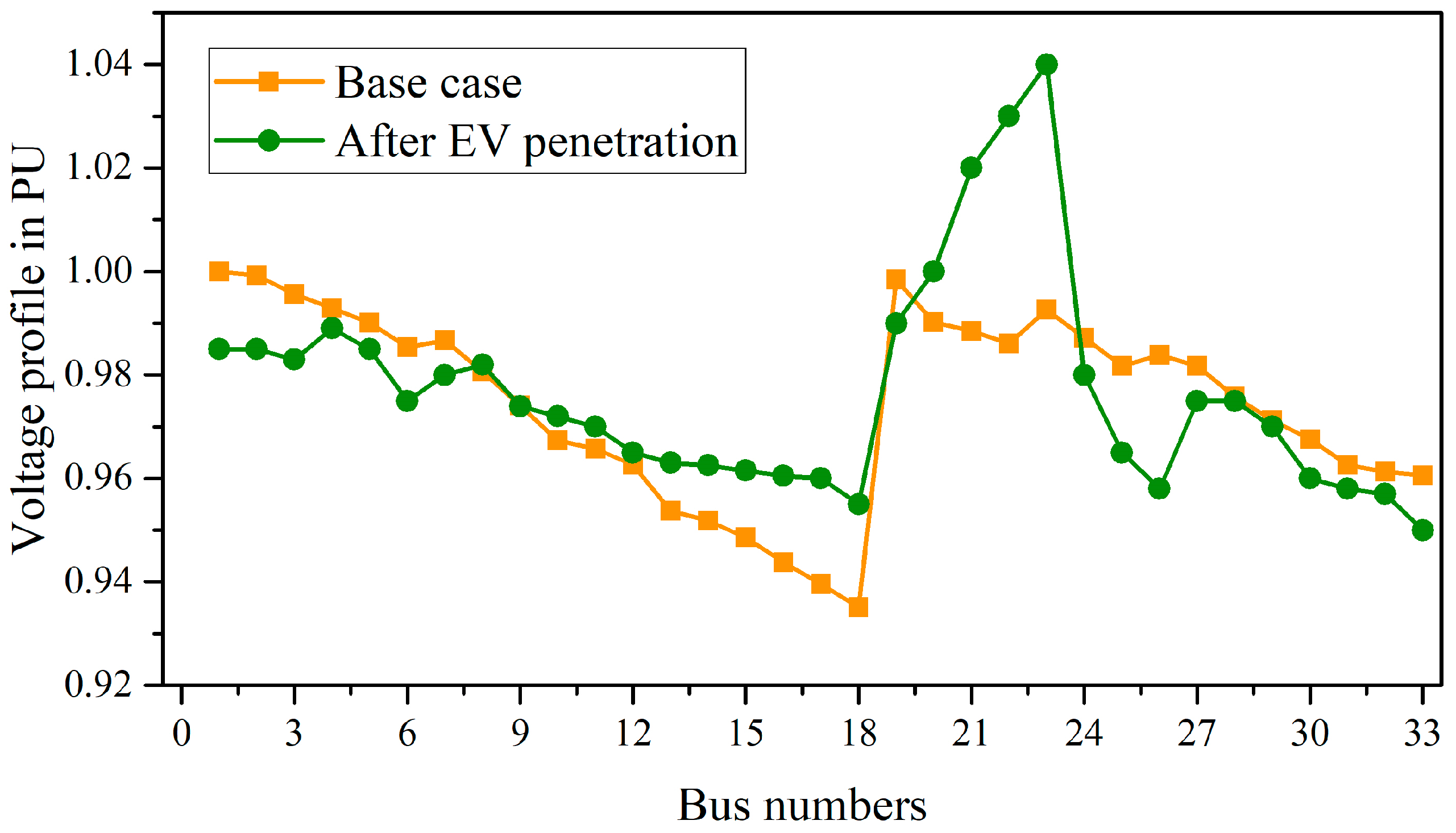

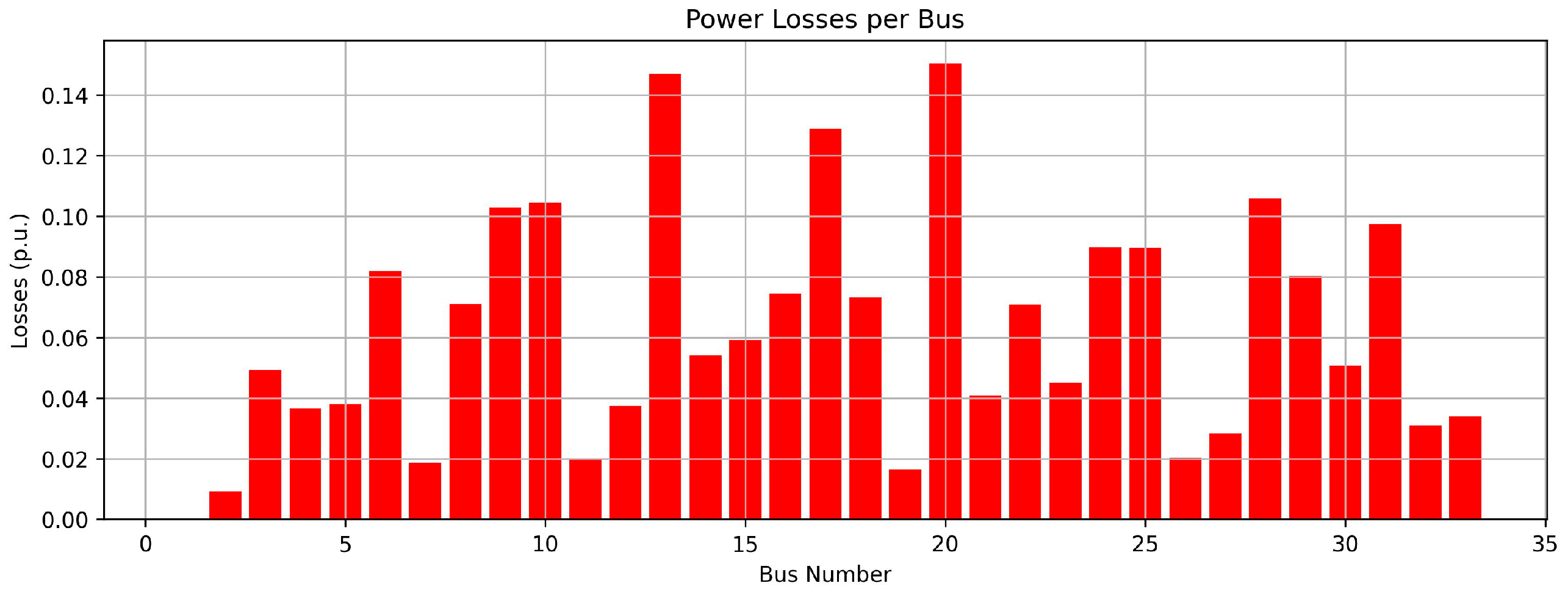

5.1. Impact on Voltage Profile

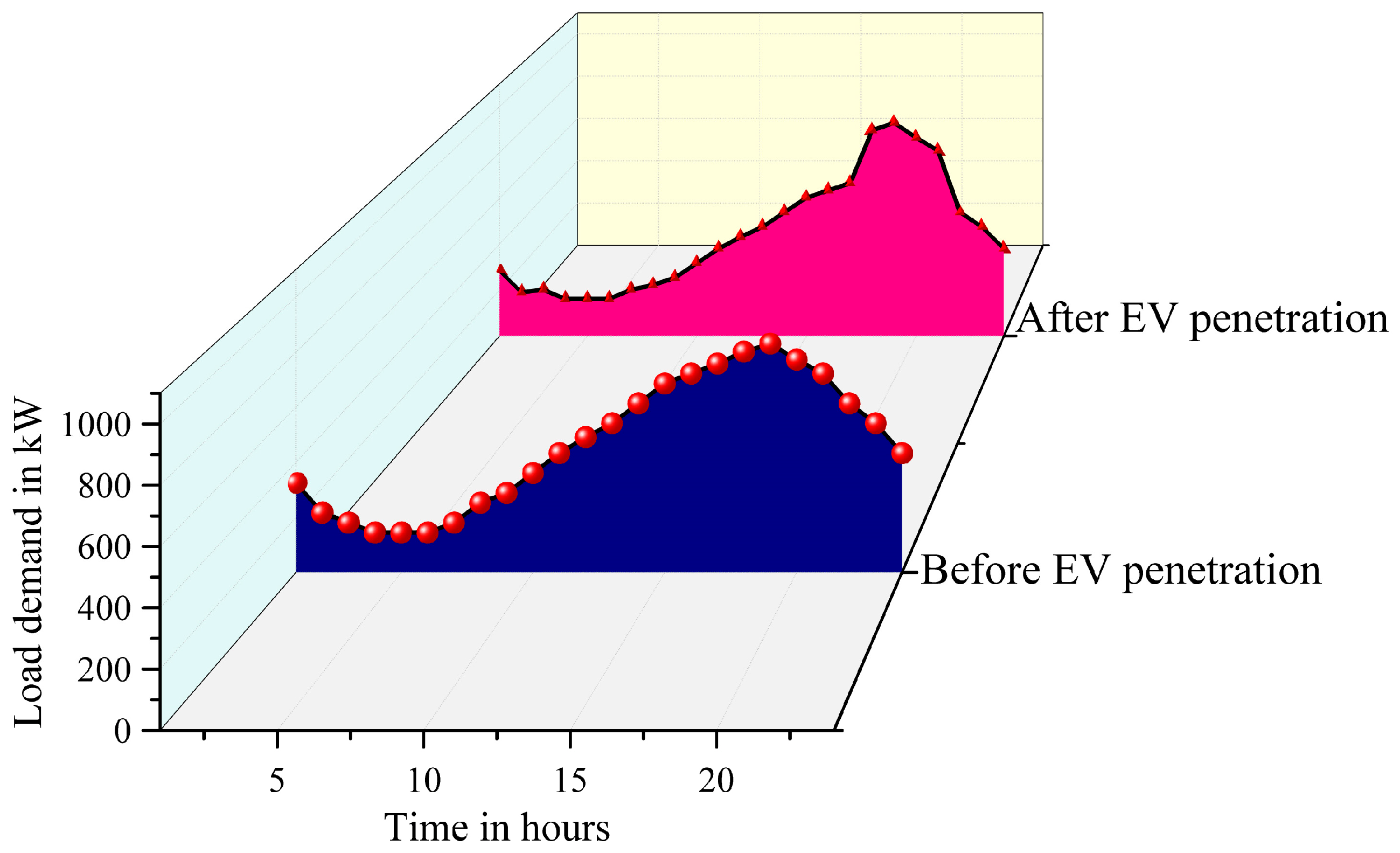

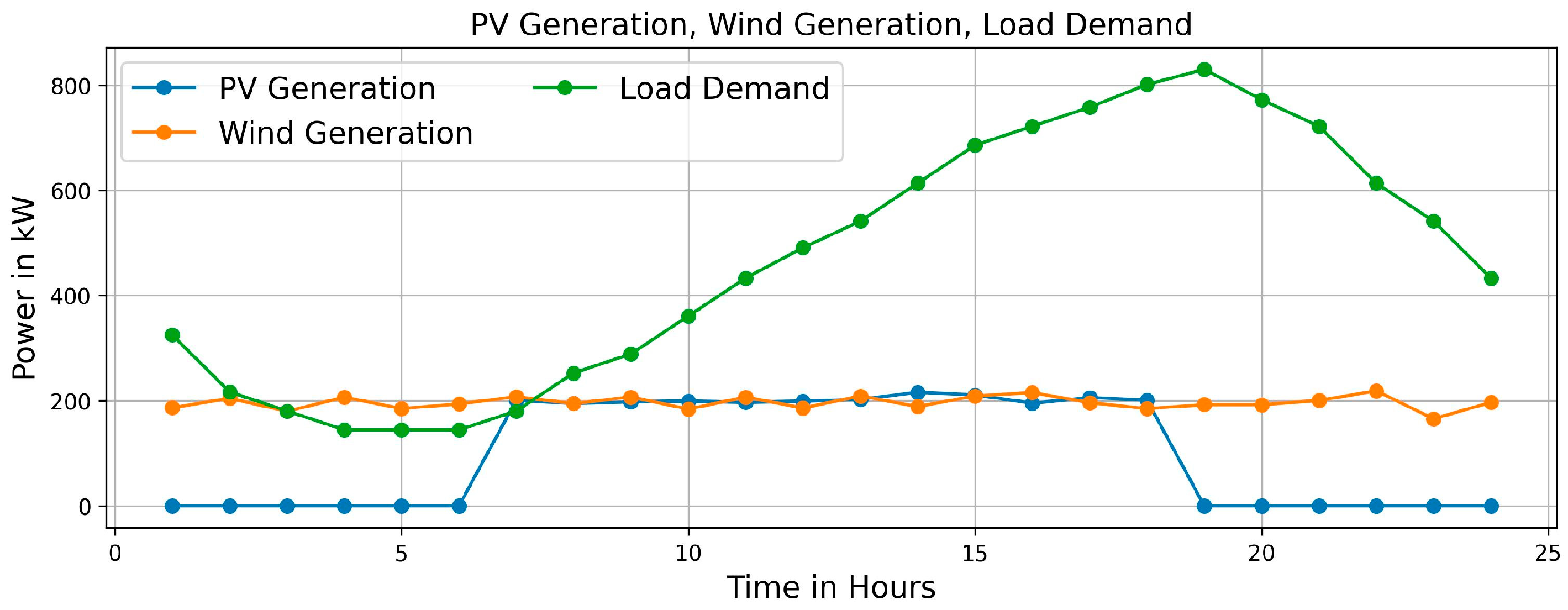

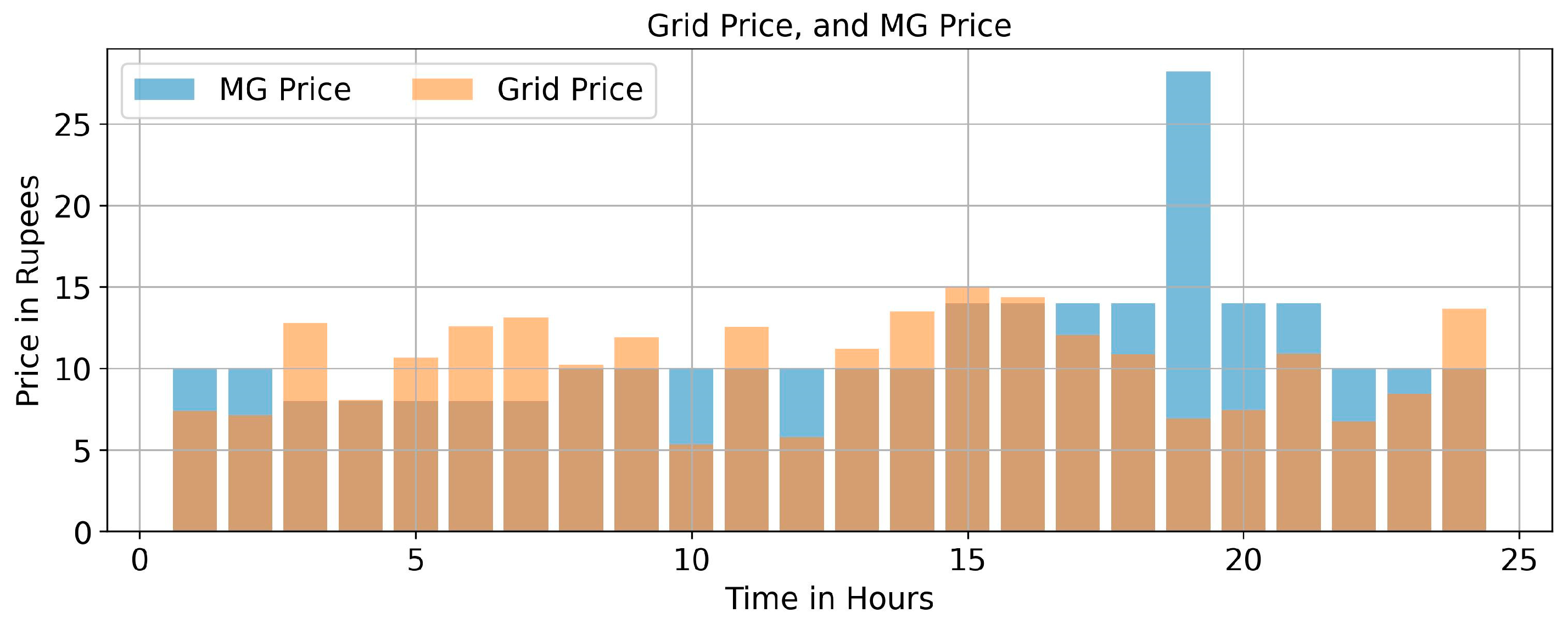

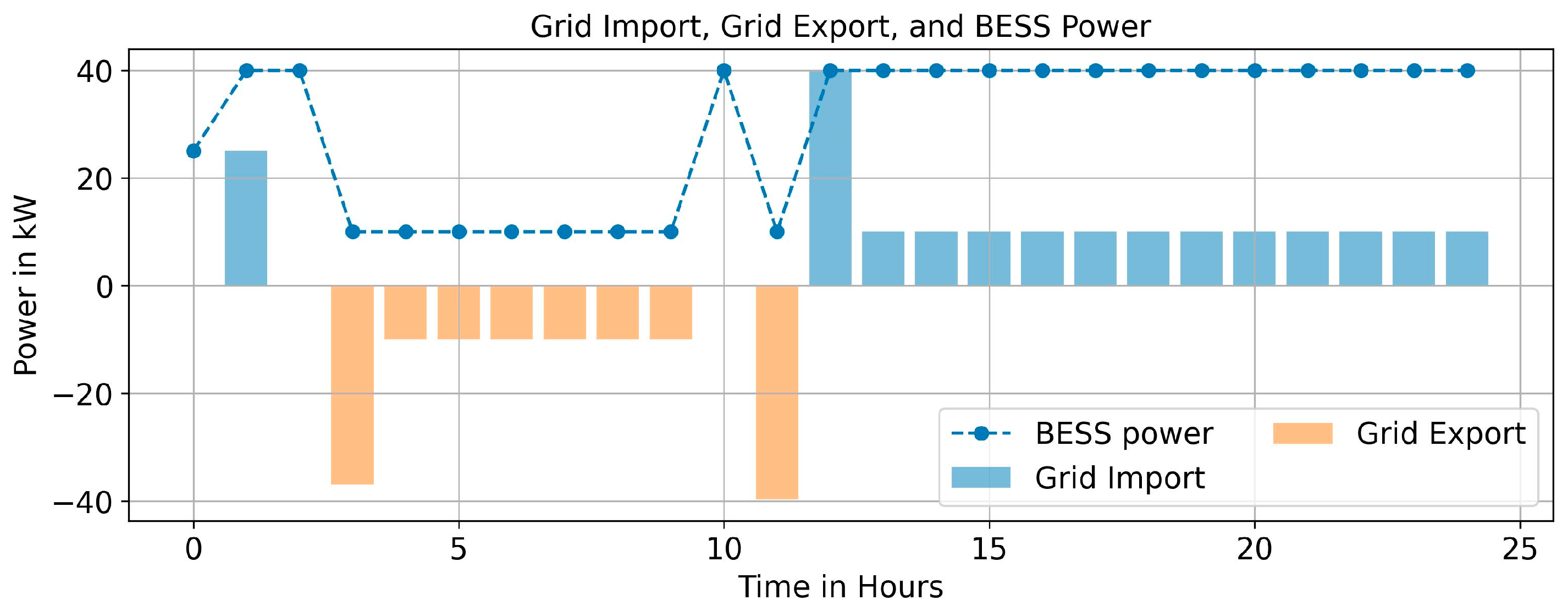

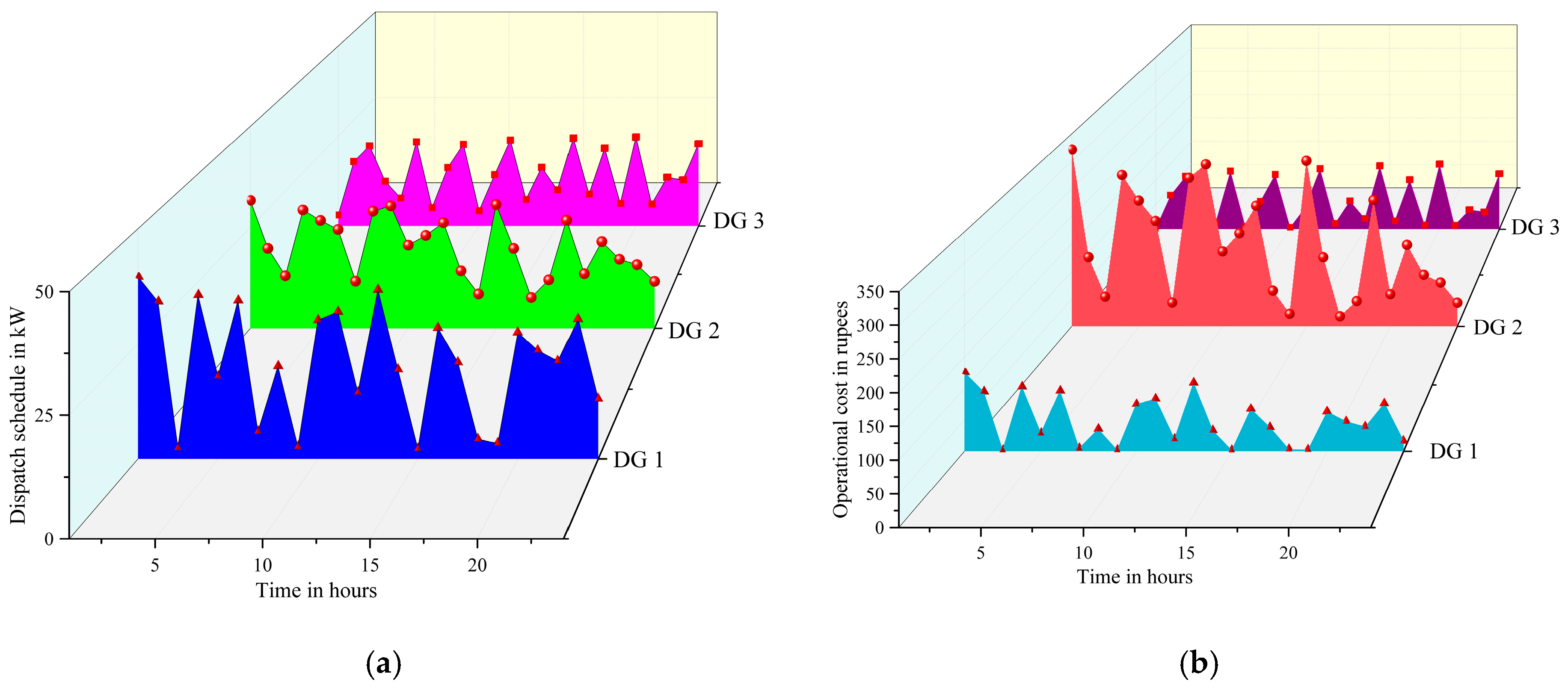

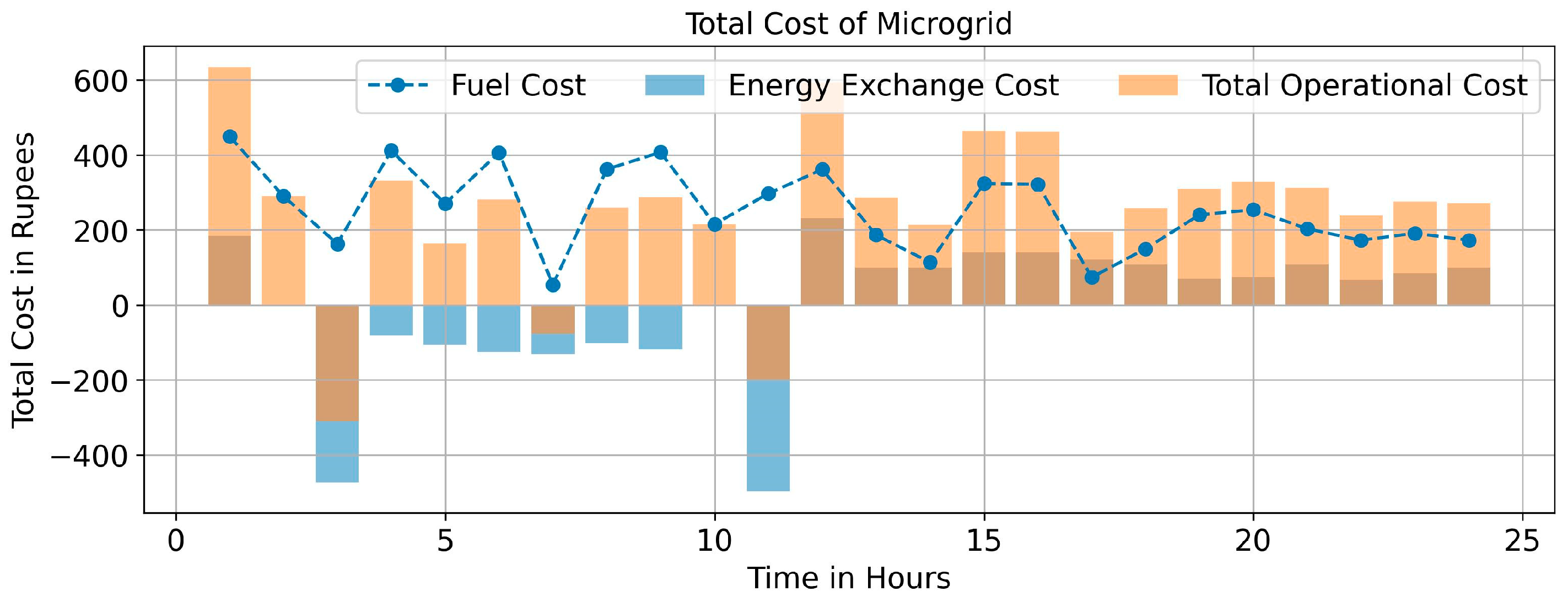

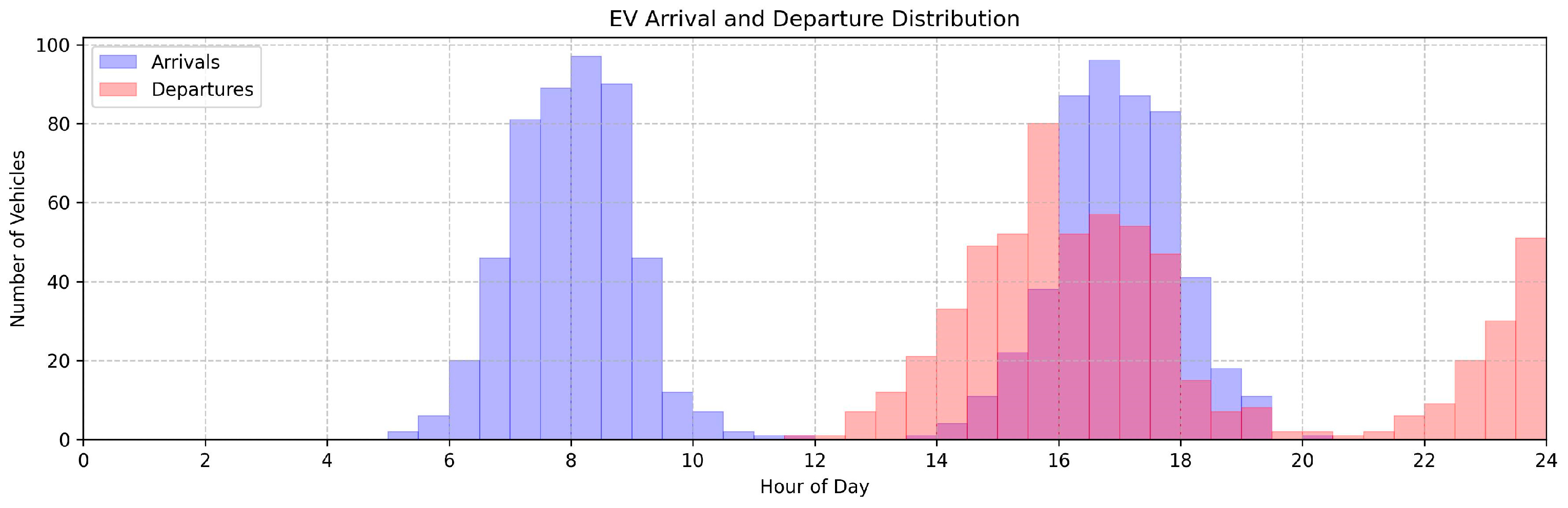

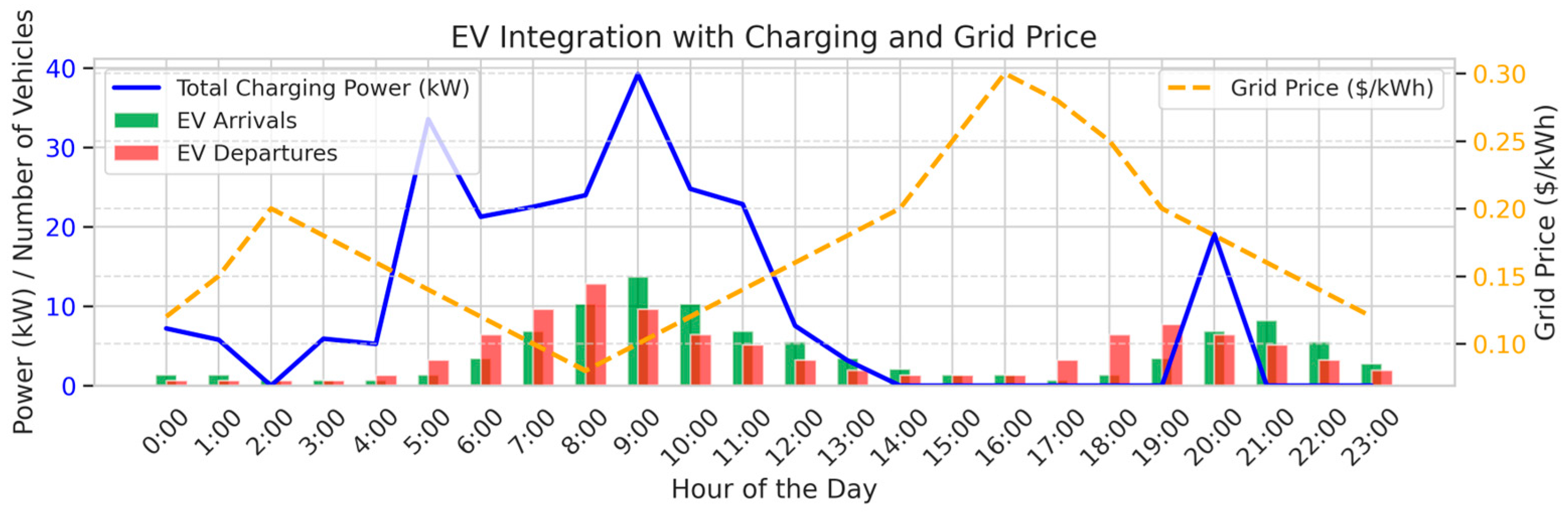

5.2. Impact of EV Penetration on the Scheduling of MG Resources

5.3. Impact of EV Uncertainties on Operational Cost

5.4. Potential Limitations of the Proposed Work

6. Conclusions

- Future scope:

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MG | Microgrid |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-grid |

| DER | Distributed energy resources |

| PV | Solar photovoltaic |

| BESS | Battery energy storage systems |

| WT’s | Wind turbines |

| LR | Lagrangian relaxation |

| ASFO | Adaptive sheep flock optimization |

| SFO | Sheep flock optimization |

| FCS | Fast-charging stations |

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| DG | Diesel generator |

| FC | Fuel cell |

| MT | Micro turbine |

| SoC | State of charge |

| RESs | Renewable energy sources |

| KKT | Karush-kuhn-tucker |

| MCS | Monte Carlo simulation |

| ABC | Artificial bee colony |

| GWO | Grey wolf optimization |

| WOA | Whale optimization algorithm |

| GD | Gradient descent |

| List of acronyms | |

| Power generated from wind | |

| Rated wind power | |

| Cut-in speed | |

| Cut-out speed | |

| Power generation through solar | |

| Critical insolation | |

| Standard insolation | |

| Z0, Z1, and Z2 | Cost coefficients of DG |

| Fuel cost of DG | |

| Power generated from FC | |

| X0, X1 | Cost coefficients of FC |

| Cost of energy produced from FC | |

| Cost of energy produced from MT | |

| Power produced from MT | |

| Total cost of the MG | |

| Energy exchange cost | |

| Operational costs | |

| Lower bound on voltage | |

| Upper bound on voltage | |

| Lower bound on active power | |

| Upper bound on active power | |

| Lower bound on reactive power | |

| Upper bound on reactive power | |

| Lower bound on active power in line i and j | |

| Upper bound on active power in line i and j | |

| State of charge of MG at time t | |

| , | Charge and discharge status |

| , | Charge and discharge power |

| , | Efficiency of BESS during Charging and discharging |

References

- Boruah, D.; Chandel, S.S. Techno-economic feasibility analysis of a commercial grid-connected photovoltaic plant with battery energy storage-achieving a net zero energy system. J. Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, M. Evolutionary Game Dynamics between Distributed Energy Resources and Microgrid Operator: Balancing Act for Power Factor Improvement. Electronics 2024, 13, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Sakr, E.K.; Abo-Adma, M.; Elazab, R. A comprehensive review of advancements and challenges in reactive power planning for microgrids. Energy Inf. 2024, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R, S.; Sankaranarayanan, V. Optimal Scheduling of Electric Vehicle Charging at Geographically Dispersed Charging Stations with Multiple Charging Piles. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2022, 20, 672–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Carrel, A.L.; Gore, C.; Shi, W. Environmental and Economic Impact of Electric Vehicle Adoption in the U.S. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 045011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, T.R.; Singh, B.; Majeau-Bettez, G.; Strømman, A.H. Comparative Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Conventional and Electric Vehicles. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 17, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nour, M.; Chaves-Ávila, J.P.; Magdy, G.; Sánchez-Miralles, Á. Review of Positive and Negative Impacts of Electric Vehicles Charging on Electric Power Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bharati, G.R.; Paudyal, S.; Ceylan, O.; Bhattarai, B.P.; Myers, K.S. Coordinated Electric Vehicle Charging with Reactive Power Support to Distribution Grids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, P.; Ahmad, I.; Habibi, D.; Kothapalli, G.; Masoum, M.A.S. Reducing the Impacts of Electric Vehicle Charging on Power Distribution Transformers. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 210183–210193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, B.; Ceylan, O.; Ozdemir, A. Distributed energy resource allocation using multi-objective grasshopper optimization algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 201, 107564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Chakraborty, A.K. Allocation of electric vehicle charging station considering uncertainties. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2021, 25, 100422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Farnoosh, A.; Chen, S.; Li, Y. GIS-Based Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization of charging stations for electric vehicles. Energy 2019, 169, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Le, W.; Guo, Z.; He, Z. Data-driven intelligent location of public charging stations for electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Elyousr, F.K.; Sharaf, A.M.; Darwish, M.M.F.; Lehtonen, M.; Mahmoud, K. Optimal scheduling of DG and EV parking lots simultaneously with demand response based on self-adjusted PSO and K-means clustering. Energy Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 4025–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S., S.M.; Titus, F.; Thanikanti, S.B.; M., S.S.; Deb, S.; Kumar, N.M. Charge Scheduling Optimization of Plug-In Electric Vehicle in a PV Powered Grid-Connected Charging Station Based on Day-Ahead Solar Energy Forecasting in Australia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, H.; Buffat, R.; Bucher, D.; Hamper, J.; Raubal, M. Using rooftop photovoltaic generation to cover individual electric vehicle demand—A detailed case study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.E.; Assi, C.; Tushar, M.H.K.; Yan, J. Optimal Scheduling of EV Charging at a Solar Power-Based Charging Station. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 4221–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Hasanien, H.M.; Rehman, A.U.; Turky, R.A.; Elkadeem, M.R. Optimal scheduling and techno-economic analysis of electric vehicles by implementing solar-based grid-tied charging station. Energy 2023, 267, 126560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, K.; Hu, B.; Shao, C.; Wang, Y.; Pan, C. Reliability–flexibility integrated optimal sizing of second-life battery energy storage systems in distribution networks. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 2177–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Park, J.; Lee, K. Optimal Scheduling for Electric Vehicle Charging under Variable Maximum Charging Power. Energies 2017, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Lee, S.; Nengroo, S.H.; Har, D. Development of Charging/Discharging Scheduling Algorithm for Economical and Energy-Efficient Operation of Multi-EV Charging Station. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leou, R.-C.; Hung, J.-J. Optimal Charging Schedule Planning and Economic Analysis for Electric Bus Charging Stations. Energies 2017, 10, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tostado-Véliz, M.; Kamel, S.; Hasanien, H.M.; Arévalo, P.; Turky, R.A.; Jurado, F. A stochastic-interval model for optimal scheduling of PV-assisted multi-mode charging stations. Energy 2022, 253, 124219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, N.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Yang, J. Optimal scheduling of electric vehicle charging operations considering real-time traffic condition and travel distance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 118941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Mishra, P.; Mathur, H.D. Optimal scheduling of mobile and stationary electric vehicle charging stations in a distribution system with stochastic loading. Energy 2025, 326, 136305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yin, W.; Wang, P.; Ji, J. EV charging load forecasting and optimal scheduling based on travel characteristics. Energy 2024, 311, 133389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotge, R.; Snow, Y.; Farahani, S.; Lukszo, Z.; van Wijk, A. Optimized Scheduling of EV Charging in Solar Parking Lots for Local Peak Reduction under EV Demand Uncertainty. Energies 2020, 13, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurz, G.; Thorn, P. Escaping the No Free Lunch Theorem: A Priori Advantages of Regret-Based Meta-Induction. J. Exp. Theor. Artif. Intell. 2024, 36, 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abualigah, L.; Sheikhan, A.; Ikotun, A.M.; Abu Zitar, R.; Alsoud, A.R.; Al-Shourbaji, I.; Hussien, A.G.; Jia, H. Particle swarm optimization algorithm: Review and applications. In Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms; Laith, A., Ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 1–14. ISBN 9780443139253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amponsah, A.A.; Han, F.; Ling, Q.H.; Kudjo, P.K. An enhanced class topper algorithm based on particle swarm optimizer for global optimization. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barenji, R.V.; Nejad, M.G.; Asghari, I. Optimally Sized Design of a Wind/Photovoltaic/Fuel Cell off-Grid Hybrid Energy System by Modified-Gray Wolf Optimization Algorithm. Energy Environ. 2018, 29, 1053–1070. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26979275 (accessed on 16 April 2018). [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.A.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Walker, S.L.; Taylor, P.; Sanjari, M.J. Mohammad Javad Sanjari, Optimal placement and sizing of battery energy storage system for losses reduction using whale optimization algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2019, 26, 100892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algabalawy, M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Mekhamer, S.F.; Aleem, S.H.A. Considerations on optimal design of hybrid power generation systems using whale and sine cosine optimization algorithms. J. Electr. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2018, 5, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothireddy, K.M.R.; Vuddanti, S. Alternating direction method of multipliers based distributed energy scheduling of grid connected microgrid by considering the demand response. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothireddy, K.M.R.; Vuddanti, S. Novel demand response-based stochastic optimisation in a grid-connected MG considering outlier detection and imputation. Int. J. Ambient. Energy 2024, 46, 2442602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothireddy, K.M.R.; Vuddanti, S. A Hybrid Lagrangian and Improved Class Topper Optimization for Optimal Sizing of Battery Energy Storage System. Smart Grids Energy 2025, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothireddy, K.M.R.; Vuddanti, S.; Salkuti, S.R. Optimal assortment of methods to mitigate the imbalance power in the day-ahead market. Electr. Eng. 2025, 107, 7933–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, G.; Lie, T.T.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Han, B.; Xu, J. Constrained large-scale real-time EV scheduling based on recurrent deep reinforcement learning. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 144, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Wen, J. A Cooperative Charging Control Strategy for Electric Vehicles Based on Multiagent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 8765–8775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Zhao, T.; Lee, W.-J. Real-Time Operation Management for Battery Swapping-Charging System via Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarposhti, M.A.; Colak, I.; Eguchi, K. Optimal energy management of distributed generation in micro-grids using artificial bee colony algorithm. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2021, 18, 7402–7418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, M.; Seo, Y.W. Biodegradable waste to renewable energy conversion under a sustainable energy supply chain management. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 6993–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Sheng, K.; Shu, F. Ship power load forecasting based on PSO-SVM. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 4547–4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanin-Villa, D.; Grisales-Noreña, L.F.; Montoya, O.D. Coordinated Active–Reactive Power Scheduling of Battery Energy Storage in AC Microgrids for Reducing Energy Losses and Carbon Emissions. Sci 2025, 7, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisales-Noreña, L.F.; Vega, H.P.; Montoya, O.D.; Botero-Gómez, V.; Sanin-Villa, D. Cost Optimization of AC Microgrids in Grid-Connected and Isolated Modes Using a Population-Based Genetic Algorithm for Energy Management of Distributed Wind Turbines. Mathematics 2025, 13, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Generation | Cost Coefficients in Rupees | Inequality Constraints | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z0 | Z1 | Z2 | Lower Limit in kW | Upper Limit in kW | |

| DG 1 | 0.010 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 150 |

| DG 2 | 0.020 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 50 |

| DG 3 | 0.015 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 150 |

| PV | - | - | - | 0 | 250 |

| Wind | - | - | - | 0 | 200 |

| Parameter | Number |

|---|---|

| Number of agents | 30 |

| Maximum number of iterations | 100 |

| Dimension | 96 = 24 × 4 |

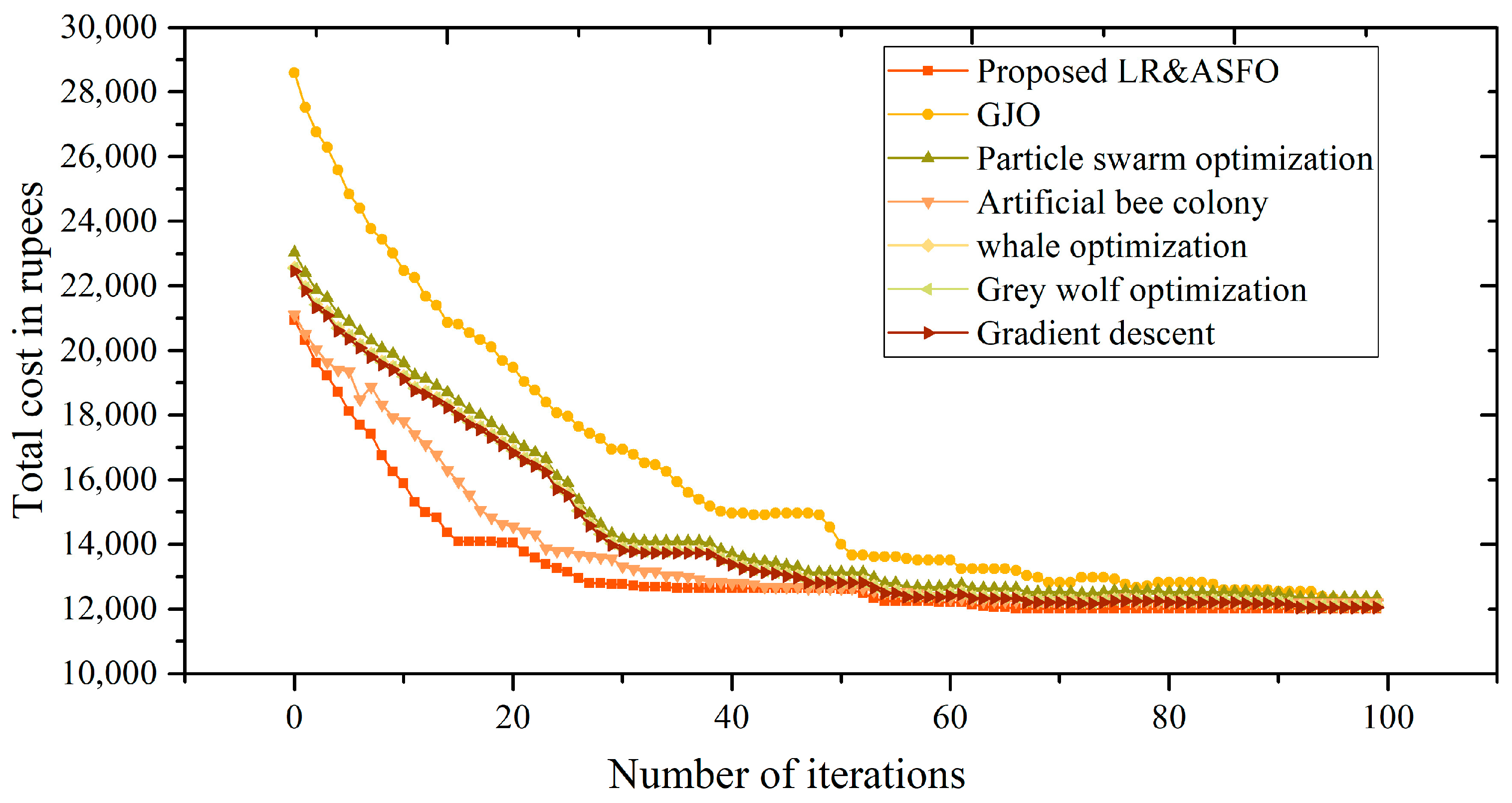

| Algorithm | Final Total Cost (Rupees) | Iterations to Converge | Relative Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed LR&ASFO | 12,016.97 (133.59 USD) | 30 | High |

| GJO | 12,284.67 (136.57 USD) | 60 | Moderate |

| PSO | 12,358 (138.38 USD) | 45 | Moderate |

| ABC | 12,203 (135.66 USD) | 65 | Low |

| Whale Optimization | 12,111.13 (134.64 USD) | 70 | Low |

| GWO | 12,098.77 (134.57 USD) | 80 | Low |

| GD | 12,049.3 (133.98 USD) | 80 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Panda, S.; Narra, S.; Salkuti, S.R. A Hybrid Lagrangian Relaxation and Adaptive Sheep Flock Optimization to Assess the Impact of EV Penetration on Cost. World Electr. Veh. J. 2026, 17, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010011

Panda S, Narra S, Salkuti SR. A Hybrid Lagrangian Relaxation and Adaptive Sheep Flock Optimization to Assess the Impact of EV Penetration on Cost. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2026; 17(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010011

Chicago/Turabian StylePanda, Sridevi, Sumathi Narra, and Surender Reddy Salkuti. 2026. "A Hybrid Lagrangian Relaxation and Adaptive Sheep Flock Optimization to Assess the Impact of EV Penetration on Cost" World Electric Vehicle Journal 17, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010011

APA StylePanda, S., Narra, S., & Salkuti, S. R. (2026). A Hybrid Lagrangian Relaxation and Adaptive Sheep Flock Optimization to Assess the Impact of EV Penetration on Cost. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 17(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17010011