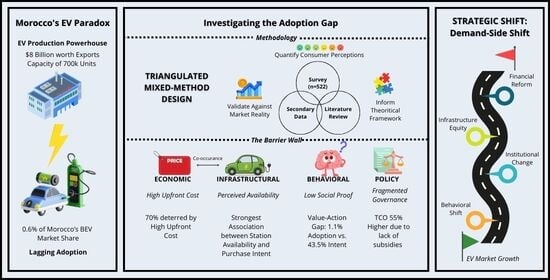

Investigating Barriers to EV Adoption in Morocco: Insights from an Emerging Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global EV Imperative

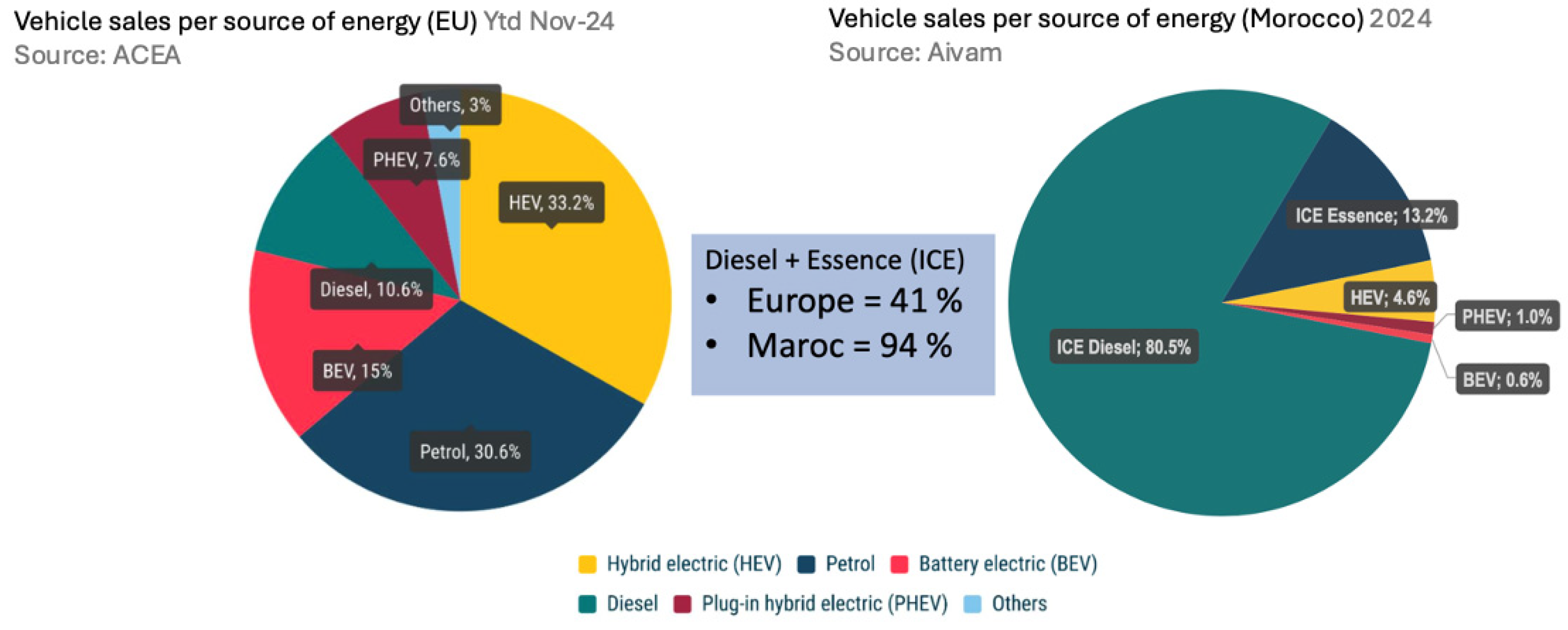

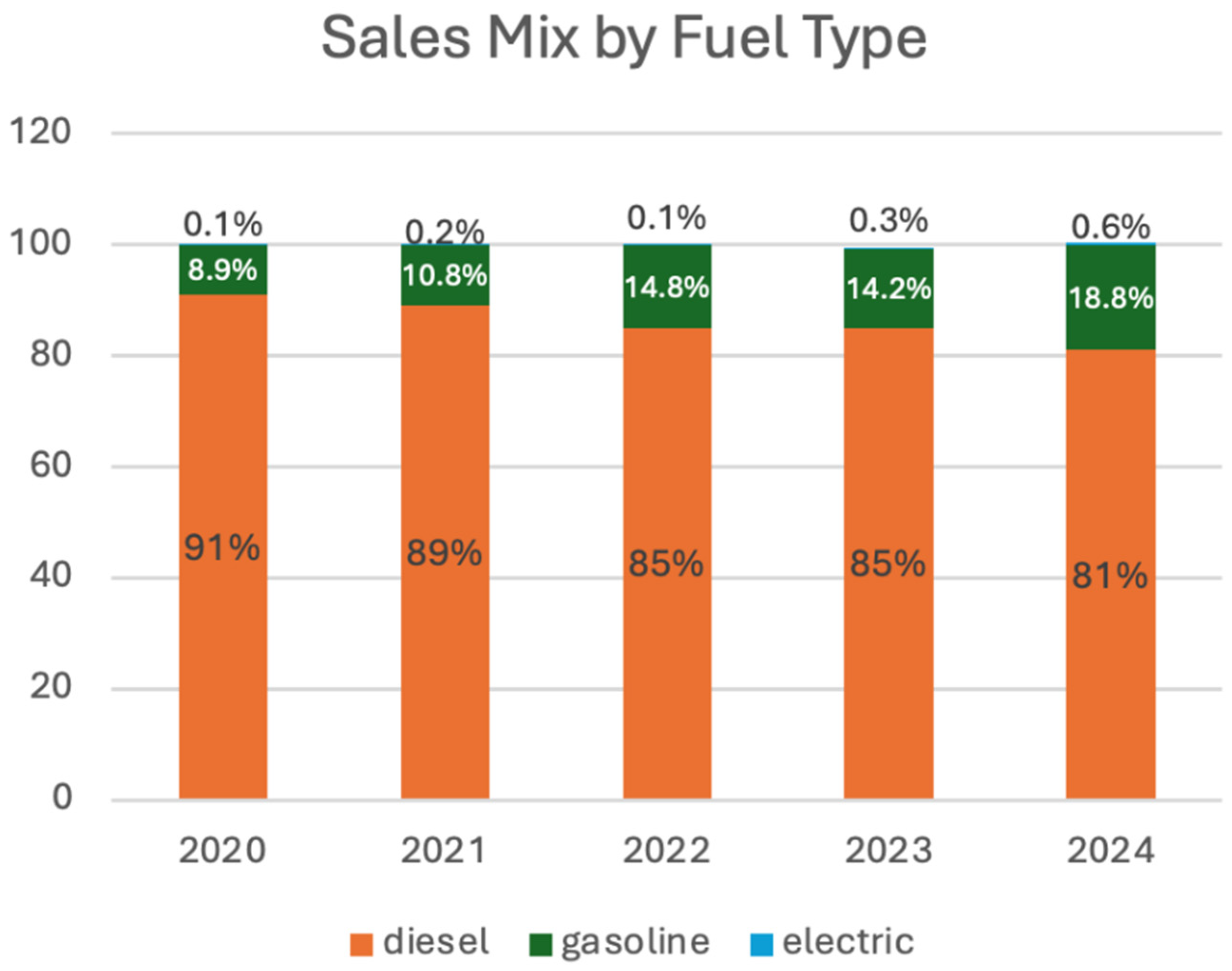

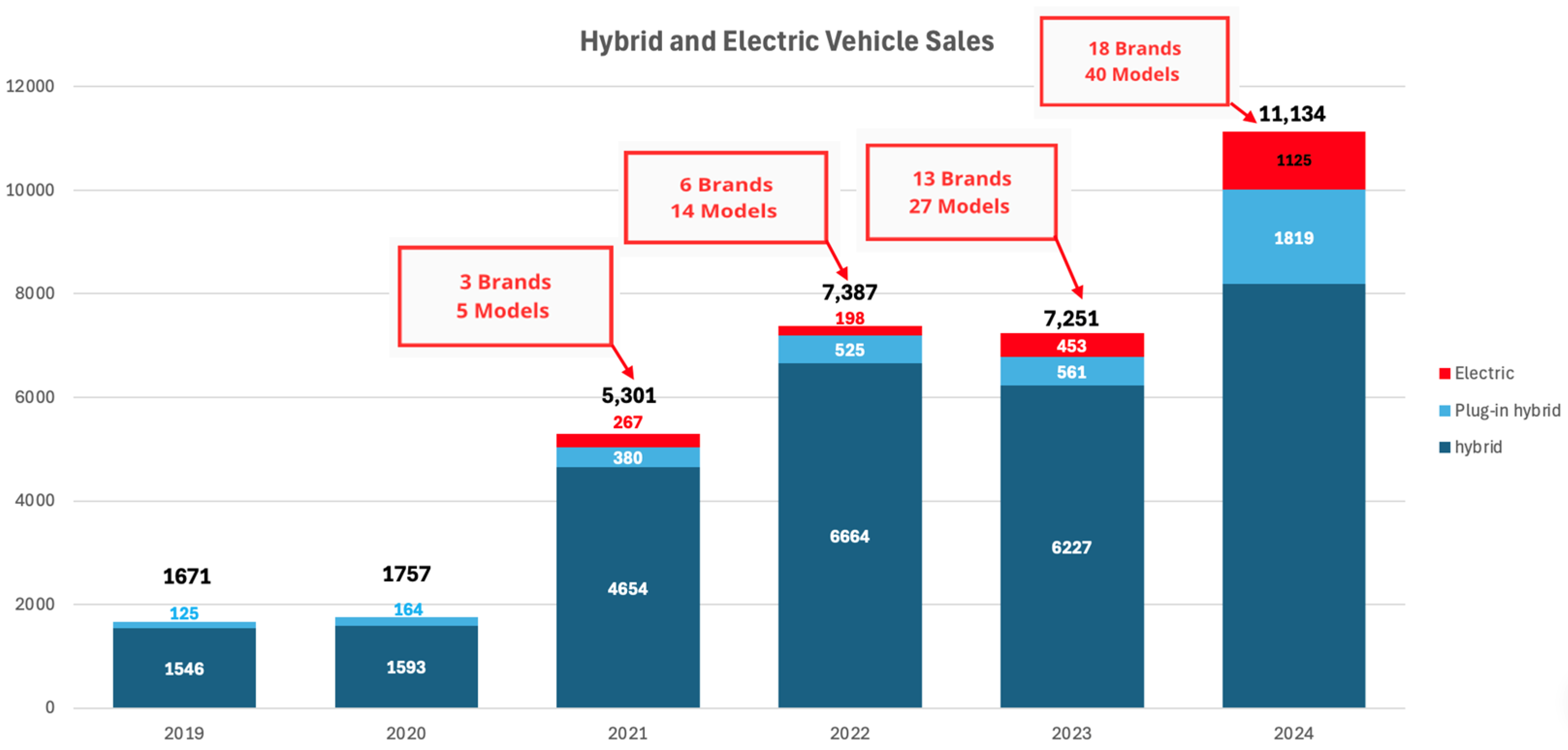

1.2. Morocco’s Automotive Paradox

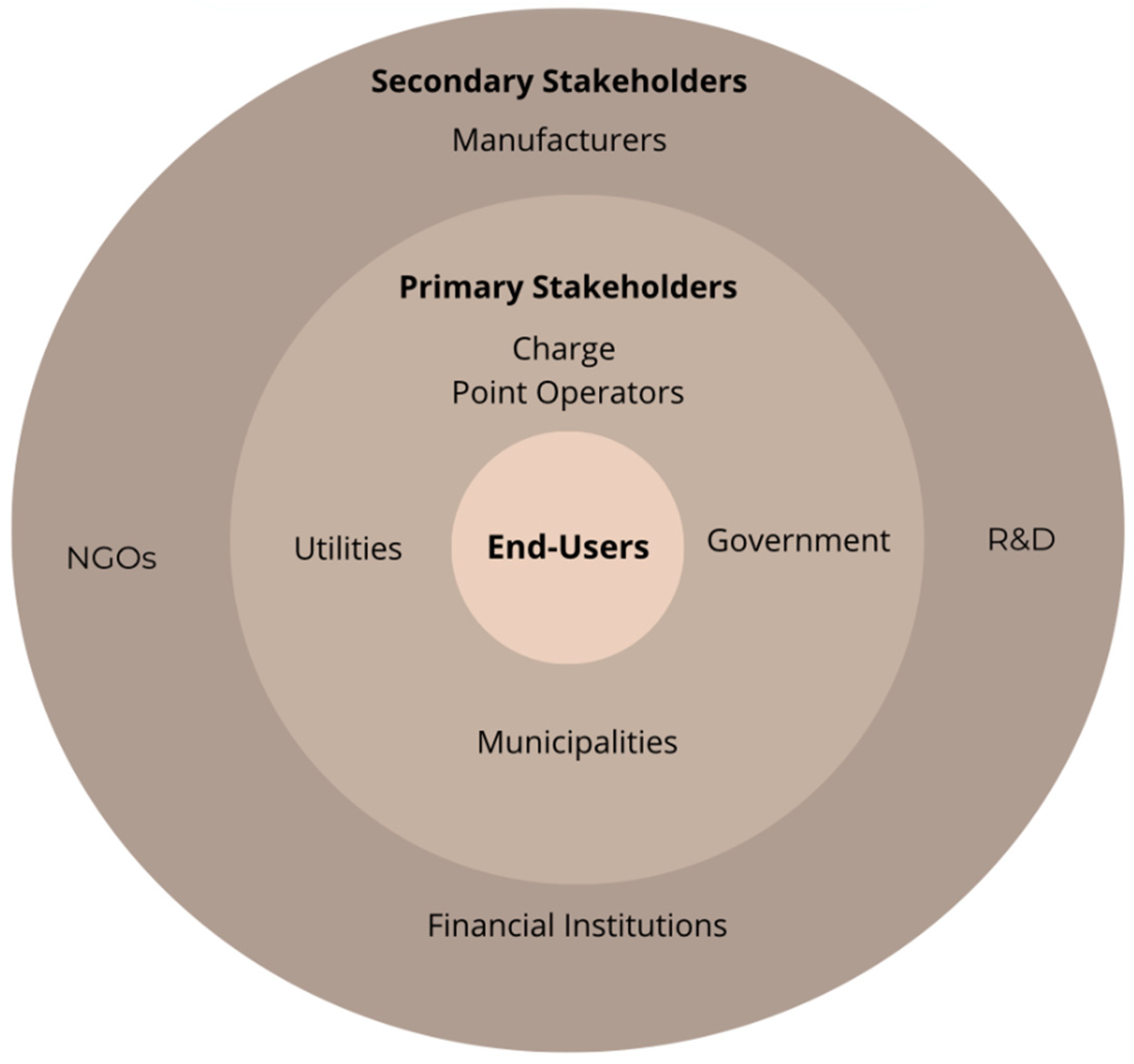

1.3. Stakeholders in Morocco’s EV Transition

- Primary stakeholders: Entities that are directly impacted by daily EV operations and infrastructure deployment. This group includes national governments responsible for setting fiscal incentives and regulatory policy, regulators and municipalities planning grid integration and charging standards utilities, charge point operators managing the physical infrastructure, the energy flow, and the pricing of public charging networks, and ultimately EV users whose adoption determines market success [17].

- Secondary stakeholders: Entities that are indirectly involved but have interests in outcomes of the transition. This group includes vehicle manufacturers and battery industries responsible for determining the local value chain and relying on market uptake for ROI, financial institutions whose role is to devise leasing and credit scheme to improve affordability, NGOs and community groups advocating for equitable access, environmental benefits, and public awareness, and, lastly, environmental and research institutions who run R&D, and provide lifecycle analyses and sustainability metrics [17].

1.4. Theoretical Framework

- Economic and Financial Barriers: Extending the cost benefit within TAM and TPB by addressing the affordability gap and financing constraints to forecast directly the influence on the perceived behavioral control and outcome beliefs in low- to middle-income contexts.

- Infrastructural and Energy Constraints: Discussing the role of technological readiness and accessibility, which are latent variables in traditional models, and primary determinants of perceived behavioral control within TPB and ease of use with TAM in emerging economies.

- Policy and Institutional Gaps: Considering the contribution of fragmented governance, regulatory uncertainty, and implementation capacity, thereby introducing a macro-institutional layer that influences subjective norms through government signaling and perceived control through incentive structure in sociotechnical analysis.

- Behavioral, Psychological, and Social Factors: Basing TPB and Diffusion theory in Morocco’s particular socio-cultural context by exploring risk perception, attitudes, and subjective norms regarding the social status of ICEs and environmental consciousness amidst economic constraints.

1.5. Literature Review

1.5.1. Economic and Financial Barriers

1.5.2. Infrastructure and Energy Constraints

1.5.3. Policy and Institutional Gaps

1.5.4. Behavioral, Psychological, and Social Factors

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

- The systematic literature review provided the theoretical foundation by (i) identifying established barrier categories from global and regional studies, (ii) informing the development of our four-dimensional analytical framework, and (iii) ensuring our research builds upon existing scholarship while addressing Morocco-specific gaps.

- The primary survey captured the end-user perspective by (i) quantifying consumer perceptions and purchase intentions, (ii) measuring the prevalence and relative importance of different barriers, (iii) analyzing interactions between economic infrastructural, and behavioral factors, and (iv) identifying consumer segments for targeted policy interventions.

- The secondary data analysis contextualized the findings within Morocco’s macro-environment by (i) providing objective metrics of EV market penetration and infrastructure deployment, (ii) substantiating the production–adoption paradox through industrial and trade data, and (iii) validating survey finding against actual national adoption patterns.

2.2. Primary Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Reliability Assessment

2.3.2. Barrier Interaction Analysis

2.3.3. Descriptive Analysis

3. Results

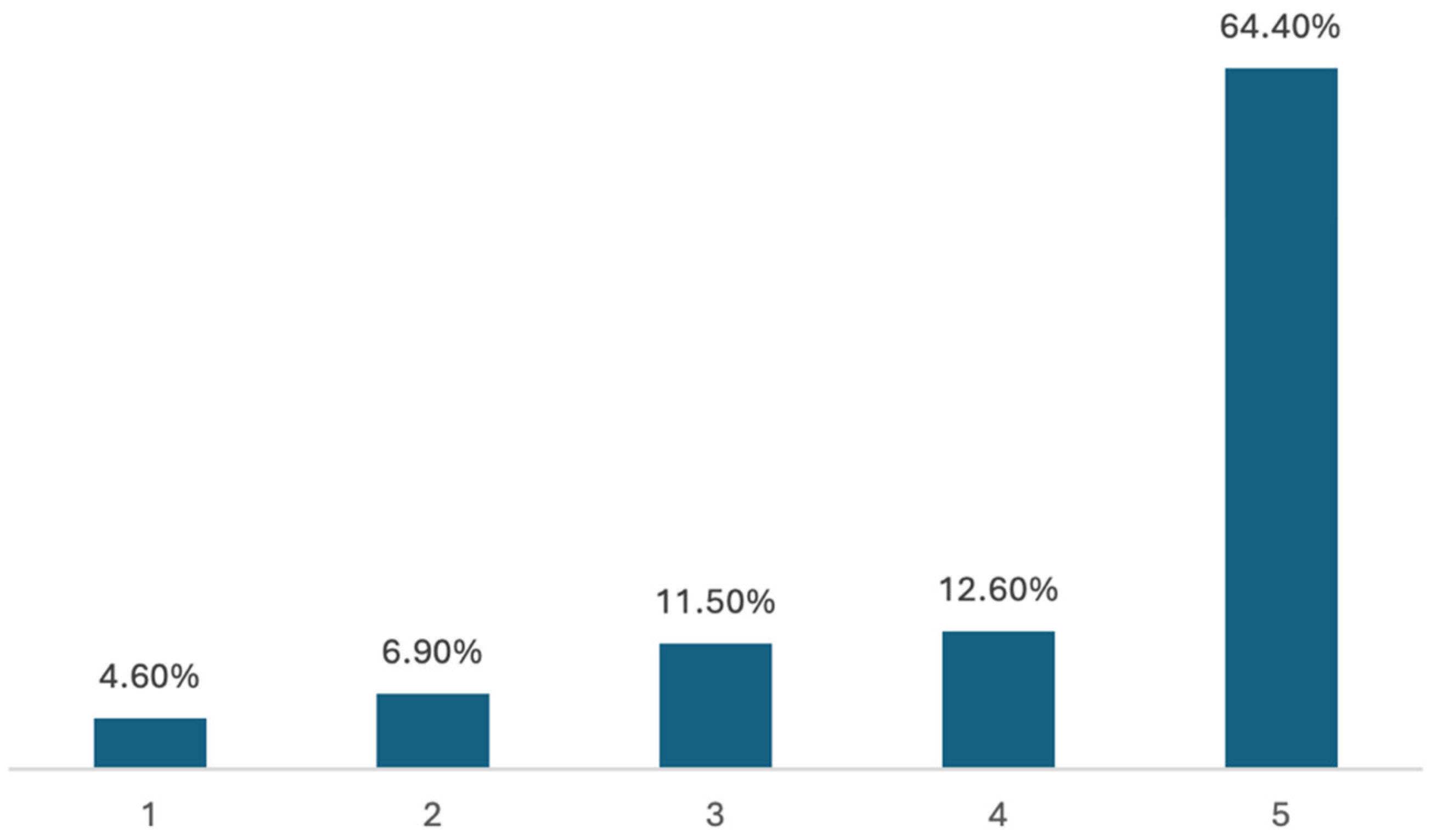

3.1. Analysis of Factors Influencing Purchase Intent

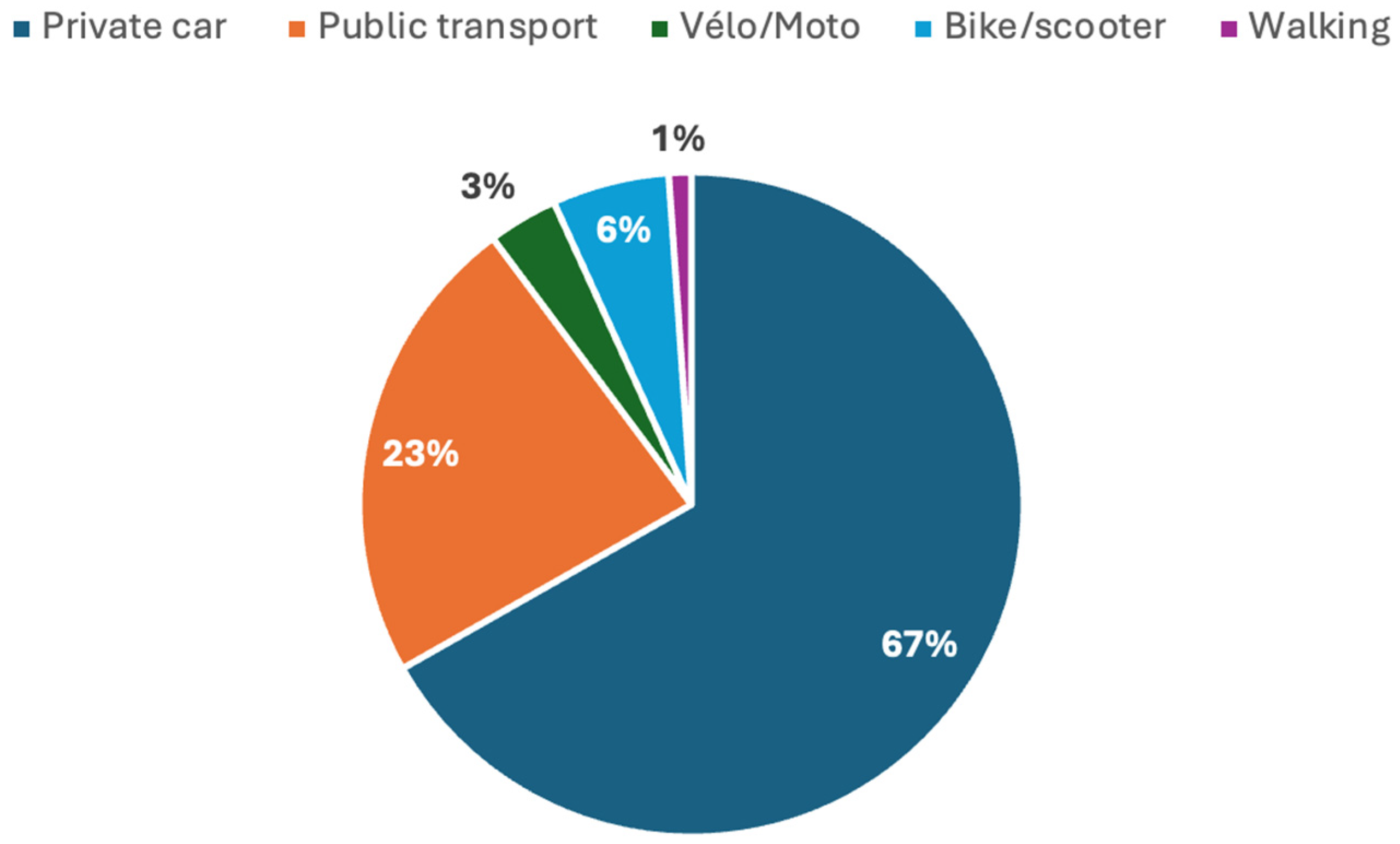

3.2. Demographic and Transport Behavior

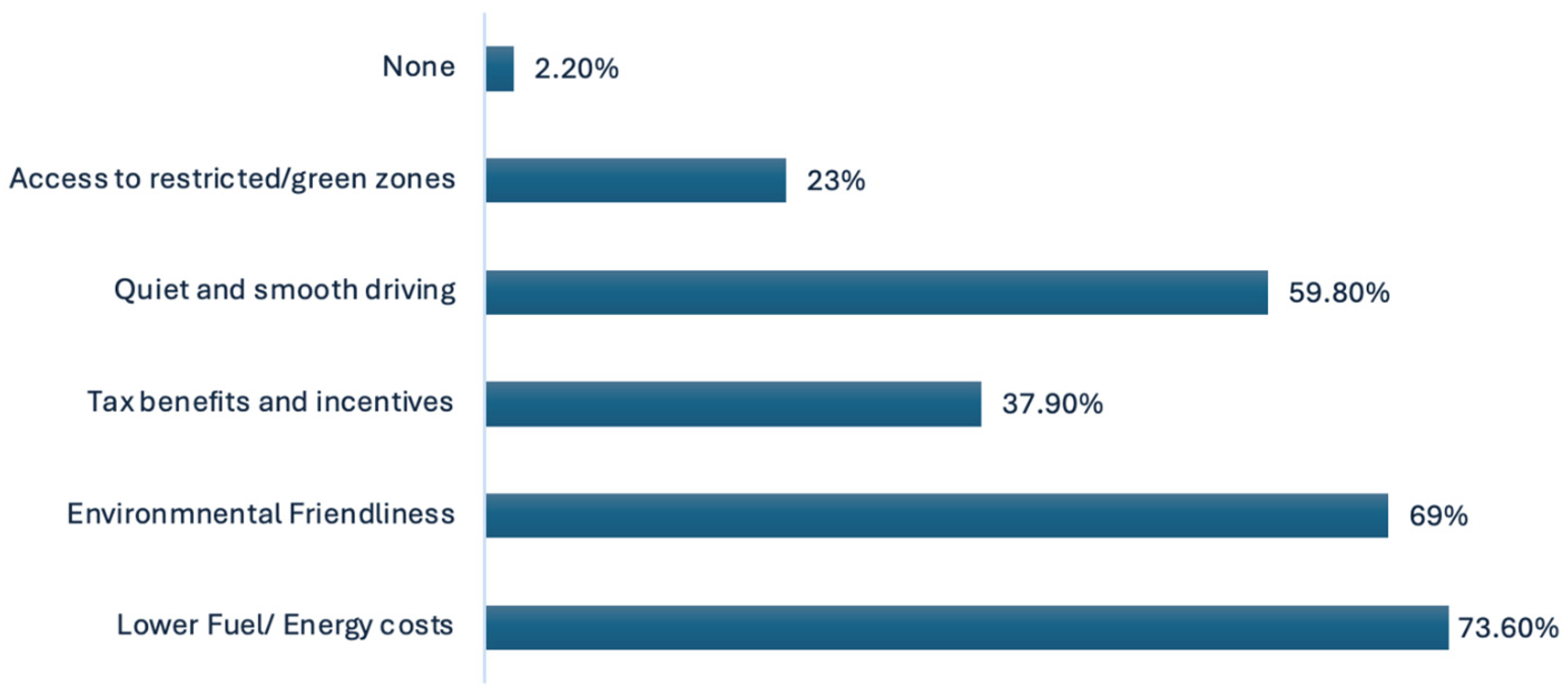

3.3. Perceptions of Economic Barriers and Benefits

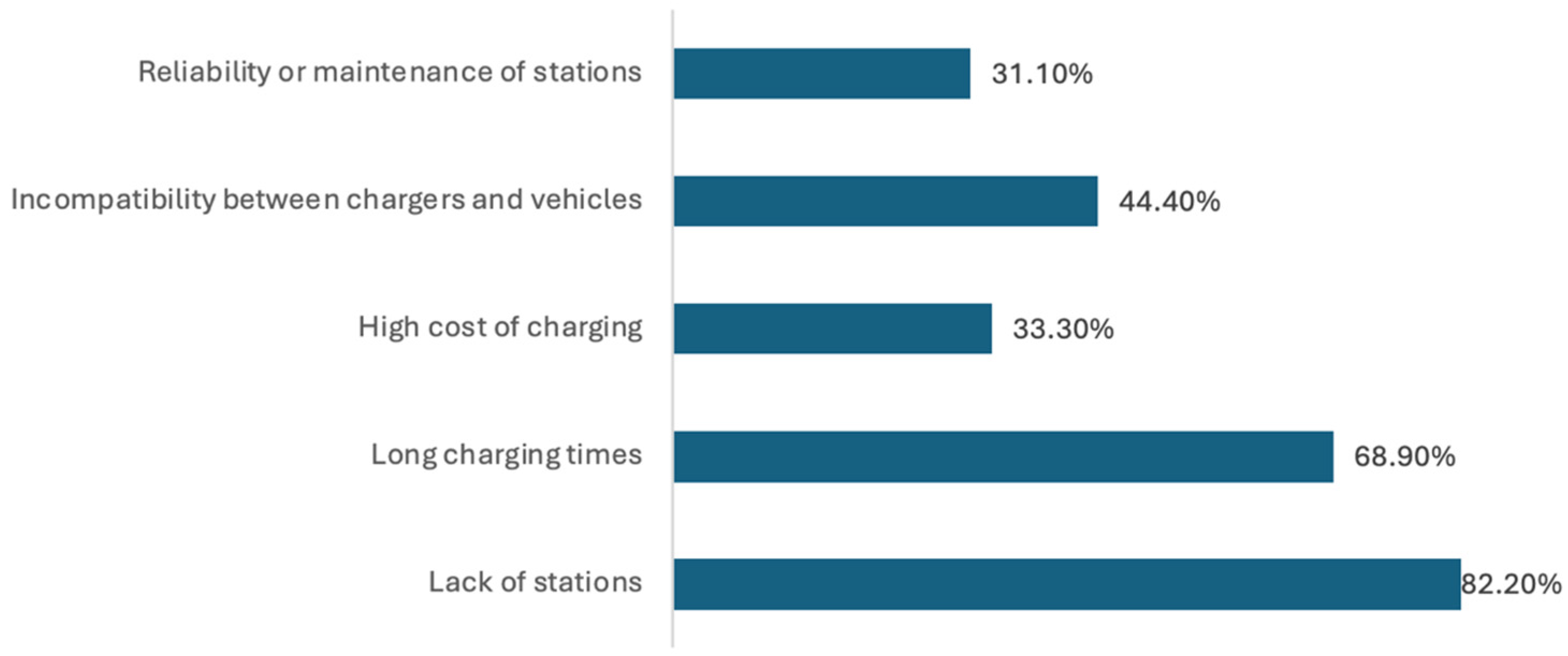

3.4. Perceptions of Infrastructural Barriers and Preferences

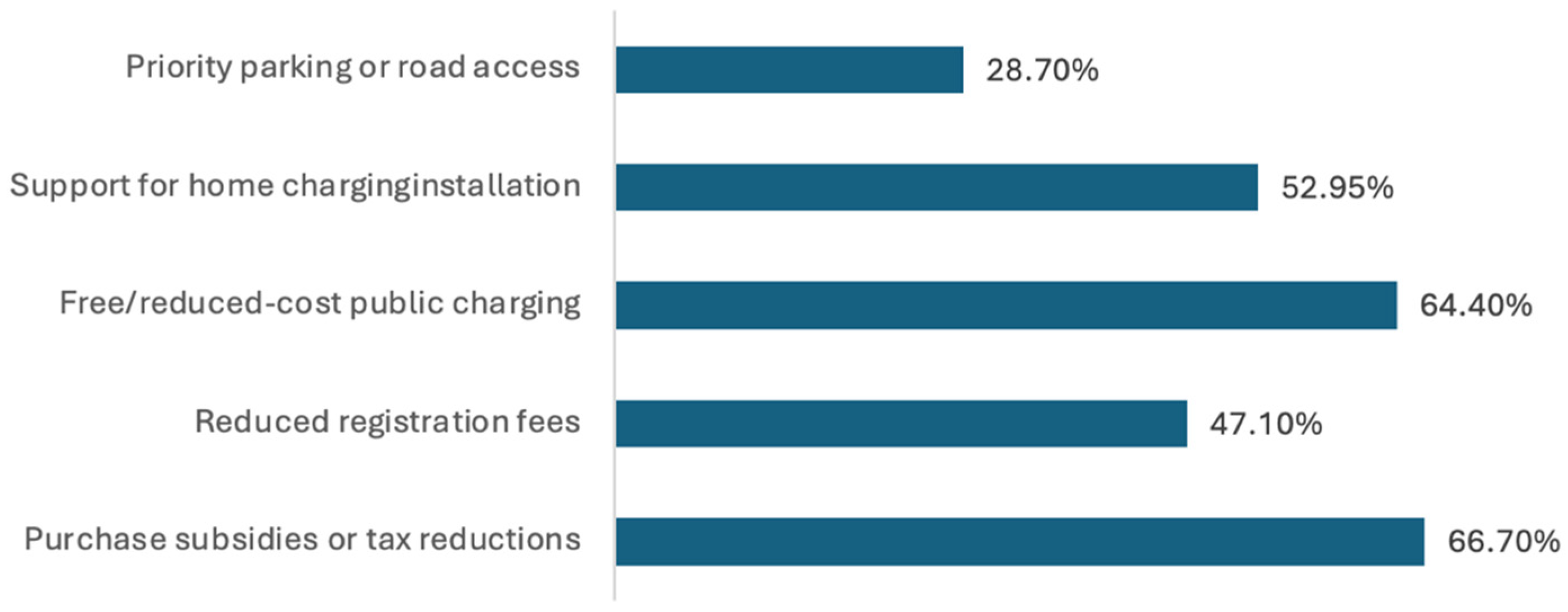

3.5. Policy Expectation and Social Influences

3.6. Response Bias and Contradiction

- Social Desirability Bias [45]: Respondents may have felt pressured to endorse EVs as the correct or socially responsible choice by the end of the survey, even if their personal circumstances or beliefs did not align with adoption. This reflects their environmental awareness without their financial commitment.

- The Value–Action Gap: This refers to the gap between one’s expressed beliefs and actual behaviors especially in sustainable contexts [46]. These respondents perceive the abstract benefit of EVs for others but not their practical application for themselves.

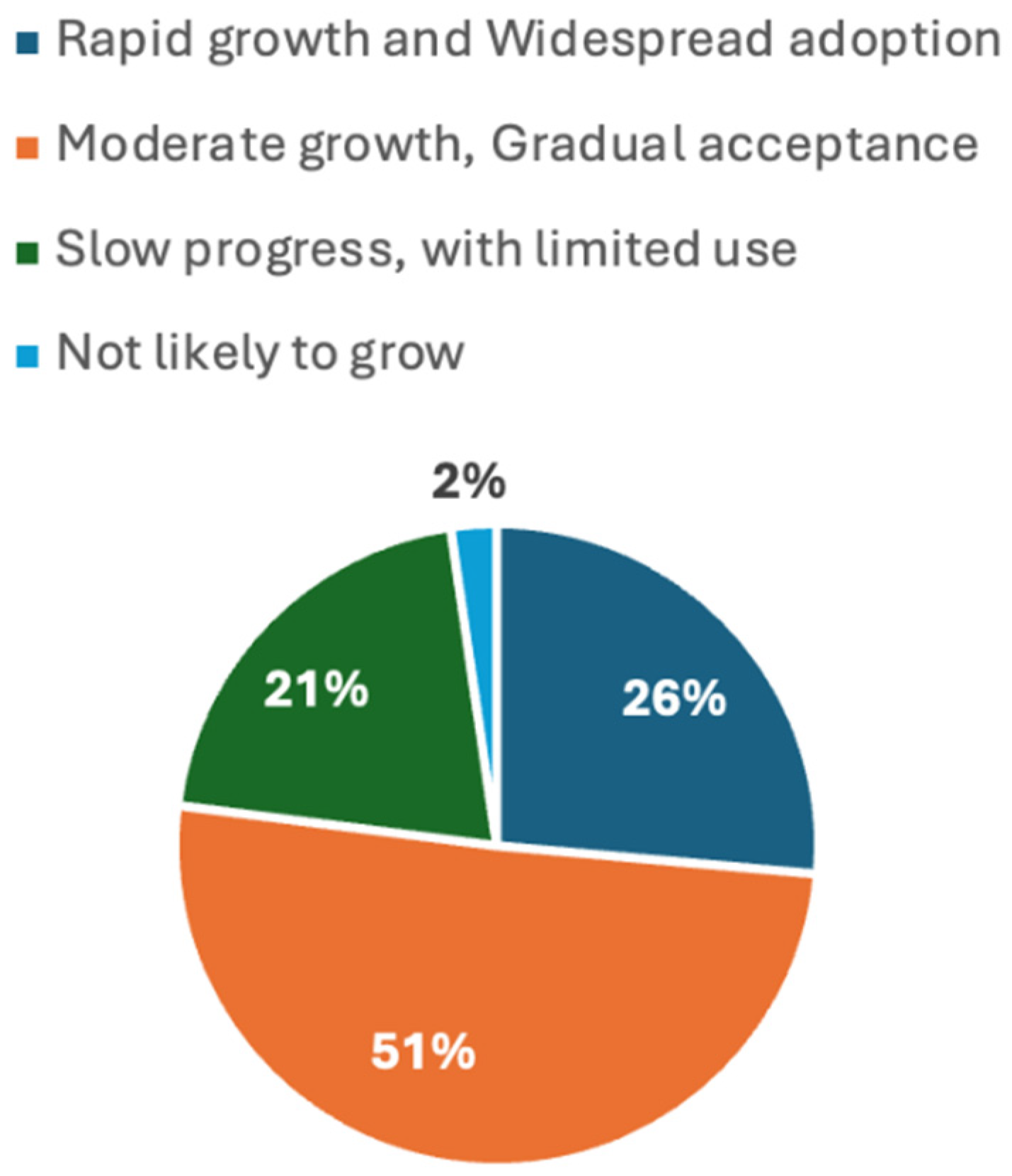

3.7. Outlook and Recommendations Based on Attitudinal Segmentation

- Enthusiasts (approx. 20%): These participants were highly motivated by environmental values and long-term cost benefits, and would adopt EVs if prices dropped or subsidies increased.

- Conditional Adopters (approx. 50%): These participants were open to the idea but constrained by cost, infrastructure, and perceived risks. They were likely to convert if barriers are addressed.

- Resistant Skeptics (approx. 30%): These participants were unlikely to adopt in the near term due to mistrust, status perception, or misinformation.

3.8. Implications for Policymakers and Industry

- Introduce targeted subsidy reform: The government should pioneer EV purchase tax credits aimed at middle-income consumers, a high-impact lever that is proven internationally but not yet embedded in Morocco’s climate finance strategy [47].

- Scale Green Loans and Guarantee Schemes: Morocco should aggressively deploy finance and de-risk tools. Tamwilcom’s Green Invest program, which financed only seven projects for 26.4 million MAD in 2023 [48], has untapped potential for expansion toward EV buyers and charging infrastructure SMEs. Similarly, the EVCAT guarantee instrument [47,48] should be explicitly extended to cover EV purchase loans to stimulate broader market participation.

- Mobilize Green Capital for Charging infrastructure: Morocco’s sovereign Green Bond Framework under AMMC [49], already used in seven successful issuances, provides an established mechanism to finance a national charging network, giving the priority to underserved and peripheral regions to ensure special equity and support long-term demand growth.

- Mandate EV readiness regulations for residential and commercial buildings: Led by AMEE, EV-ready standards for residential and commercial buildings would prevent costly future retrofits while advancing the sustainable construction objectives of the National Sustainable Development Strategy (SNDD).

- Establish a Carbon Price Signal: To improve the cost-competitiveness of EVs over ICEs, Morocco should initiate preparatory studies on carbon taxation or the cap-and-trade system in the transport sector [47].

- Implement a National ‘E-Mobility’ Awareness Strategy: Morocco should launch a coordinated national awareness campaign under the SNDD [50] to reshape consumer perceptions, clarify the total cost of EV ownership, and build trust. Demonstration projects, such as electrifying government fleets or test-driving initiatives, would increase public familiarity and confidence.

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

5.1. Economic and Industrial Measures

5.2. Infrastructure and Energy System Measures

5.3. Behavioral and Social Measures

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| CDG | Caisse de Dépôt et de Gestion (Moroccan state-owned investment group) |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| ICE | Internal Combustion Engine |

| ICEV | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle |

| IRA | Inflation Reduction Act (U.S Legislation) |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| OCP | Office Chérifien des Phosphates |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Strategies for Affordable and Fair Clean Energy Transitions; International Energy Agency (IEA): Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Li, P.; Xia, Z.; Wu, R.; Cheng, Y. Life cycle carbon footprint of electric vehicles in different countries: A review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 301, 122063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Gou, Z.; Gui, X. How electric vehicles benefit urban air quality improvement: A study in Wuhan. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association des Importateurs de Véhicles au Maroc. Performances du Marché Automobile au Maroc en 2024; AIVAM: Casablanca, Morocco, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, H.; De Santis, M.; Bayoumi, E.H.E. Electric Vehicle Adoption in Egypt: A Review of Feasibility, Challenges, and Policy Directions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samawi, G.A.; Bwaliez, O.M.; Jreissat, M.; Kandas, A. Advancing Sustainable Development in Jordan: A Business and Economic Analysis of Electric Vehicle Adoption in the Transportation Sector. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The International Transport Forum. Decarbonising Morocco’s Transport System Charting the Way Forward; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Prakhar, P.; Jaiswal, R.; Gupta, S.; Tiwari, A.K. Electric vehicles in transition: Opportunities, challenges, and research agenda—A systematic literature review. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amachraa, A. Driving the Dream: Morocco’s Rise in the Global Automotive Industry; Policy Center for the New South: Rabat, Morocco, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kasraoui, S. Morocco to Increase Electric Vehicle Production Capacity by 53% in 2025; MWN: Rabat, Morocco, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- SNECI Group. Morocco: A Rising Star in the Electric Car Industry. SNECI Group. 2023. Available online: https://www.sneci.com/en/morocco-a-rising-star-in-the-electric-car-industry/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Herve. Morocco Passes the 10,000 Electric Vehicle Mark. CAPMAD. 2025. Available online: https://www.capmad.com/others-en/morocco-passes-the-10000-electric-vehicle-mark/ (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- MAP. COBCO Company Inaugurates 1st Manufacturing Unit for Lithiurmion Battery Materials with 40,000 Tons Capacity in Jorf Lasfar. MAP. 2025. Available online: https://www.mapnews.ma/en/actualites/economy/cobco-company-inaugurates-1st-manufacturing-unit-lithiurm-ion-battery-materials (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- LG. LG Chem Teams Up with Huayou Group to Build LFP Cathode Plant in Morocco; LG: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CDG. Signature d’un Mémorandum d’Entente Entre le Groupe CDG et la société Gotion High-Tech Pour L’accompagnement du Projet de Gigafactory de Batteries au Maroc; CDG: Rabat, Morocco, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- OCP Group. OCP Group Launches a $13 Billion Green Investment Strategy. OCP Group. 2022. Available online: https://www.ocpgroup.ma/news-article/ocp-group-launches-its-new-green-investment-program-2023-2027 (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Karmaker, A.K.; Behrens, S.; Hossain, M.; Pota, H. Multi-stakeholder perspectives for transport electrification: A review on placement and scheduling of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 427, 139145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreddin, D.; El Hafdaoui, H.; Jelti, F.; Boumelha, A.; Khallaayoun, A. Inhibitors of Battery Electric Vehicle Adoption in Morocco. World Electr. Veh. 2023, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DACIA. Offre Spring. DACIA. Available online: https://www.dacia.ma/offres/offre-spring.html (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Noel, L.; de Rubens, G.Z.; Kester, J.; Sovacool, B.K. Understanding the socio-technical nexus of Nordic electric vehicle (EV) barriers: A qualitative discussion of range, price, charging and knowledge. Energy Policy 2020, 138, 111292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongklaew, C.; Phoungthong, K.; Prabpayak, C.; Chowdhury, S.; Khan, I.; Yuangyai, N.; Yuangyai, C.; Techato, K. Barriers to Electric Vehicle Adoption in Thailand. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinetz, M.; Axsen, J. How policy can build the plug-in electric vehicle market: Insights from the REspondent-based Preference And Constraints (REPAC) model. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 117, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badr, I. EV Roadmap Morocco. In Proceedings of the International Conference for Sustainable Mobility & IRF Annual Conference 2022, Marrakesh, Morocco, 6 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pamidimukkala, A.; Kermanshachi, S.; Rosenberger, J.M.; Hladik, G. Barriers and motivators to the adoption of electric vehicles: A global review. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2024, 3, 100153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayabalan, S.K.; Albusaidi, A.S.O.; Negi, G.S.; Iqbal, M.I.; Al Abdulqader, H. Consumer Acceptance, Social Behavior, Driving, and Safety Issues Regarding Electric Vehicles in Oman. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BYD. BYD Seagull. BYD. Available online: https://byd-maroc.com/seagull (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Singh, A.R.; Vishnuram, P.; Alagarsamy, S.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Damaj, I.; Rathore, R.S.; Al-Wesabi, F.N.; Othman, K.M. Electric vehicle charging technologies, infrastructure expansion, grid integration strategies, and their role in promoting sustainable e-mobility. Alex. Eng. J. 2024, 105, 300–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Channi, H.K.; Kumar, R.; Rajiv, A.; Kumari, B.; Singh, G.; Singh, S.; Dyab, I.F.; Lozanović, J. A comprehensive review of vehicle-to-grid integration in electric vehicles: Powering the future. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 25, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, D.; Powell, S. Policy and pricing tools to incentivize distributed electric vehicle-to-grid charging control. Energy Policy 2025, 198, 114496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Administration. Morocco Country Commercial Guide—Energy. International Trade Administration. 2025. Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/morocco-energy (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Boulakhbar, M.; Lebrouhi, B.; Kousksou, T.; Smouh, S.; Jamil, A.; Maaroufi, M.; Zazi, M. Towards a large-scale integration of renewable energies in Morocco. J. Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagoz, E.; Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO). Power Dynamics and Global Challenges: A Critical Exploration of Energy, Climate and Industry. Int. J. Curr. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025, 8, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, I.; Bernard, M.R.; Xie, Y.; Dallmann, T. Accelerating ZEV adoption in fleets to decarbonize road transportation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Council on Clean Transportation, Werder, Germany, 21–24 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sanguesa, J.A.; Torres-Sanz, V.; Garrido, P.; Martinez, F.J.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. A Review on Electric Vehicles: Technologies and Challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 372–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Reczek, R.W.; Makov, T. How lack of knowledge on emissions and psychological biases deter consumers from taking effective action to mitigate climate change. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 52, 1475–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Brown, S. Evaluating the role of behavior and social class in electric vehicle adoption and charging demands. Energy Policy Econ. Sustain. 2021, 24, 102914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamberlain, K.; Al Majeed, S. Evaluating the Barrier Effects of Charge Point Trauma on UK Electric Vehicle Growth. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandaramurthy, V.K.; Ajmal, A.M.; Kasinathan, P.; Tan, K.M.; Yong, J.Y.; Vinoth, R. Social Acceptance and Preference of EV Users—A Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 11956–11972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, D.; Forbes Councils Member. The Road to Mass EV Adoption: Three Barriers to a Sustainable Future. Forbes. 2023. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2023/08/30/the-road-to-mass-ev-adoption-three-barriers-to-a-sustainable-future/ (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- El Hafdaoui, H.; El Aouni, M.R.; Jaija, Y.; Jelti, F.; Mabrouki, A.; Khallaayoun, A. Total Cost of Ownership Evaluation of Alternative Fuel Vehicles in Morocco. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Innovative Research in Applied Science, Engineering and Technology (IRASET), Fez, Morocco, 16–17 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Anet, J.D. Africa Housing Finance Yearbook 2022; CAHF: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Eisinga, R.; Grotenhuis, M.T.; Pelzer, B. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gower, T.; Pham, J.; Jouriles, E.N.; Rosenfield, D.; Bowen, H.J. Cognitive biases in perceptions of posttraumatic growth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 94, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, G.; Kara, A.; Spillan, J.E. Involvement matters: Navigating the value–action gap in business students’ sustainability transformation expectations—A cross-country Kano study. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 2035–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Policy Initiative; CDG Capital; MCE. Stratégie de Développement de la Finance Climat à L’horizon 2030; Sustainable Banking and Finance Network: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tamwilcom. Rapport Annuel 2023; Tamwilcom: Rabat, Morocco, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Autorité Marocaine Du Marché des Capitaux (AMMC). Guide Sur Les Green Bonds; Autorité Marocaine Du Marché des Capitaux: Rabat, Morocco, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Transition Énergétique et du Développement Durable. Plan de la Stratégie Nationale de Développement Durable (SNDD); Ministère de la Transition Énergétique et du Développement Durable: Rabat, Morocco, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cincotta, C.; Thomassen, Ø. Evaluating Norway’s electric vehicle incentives. Energy Econ. 2025, 146, 108490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. No. | Theme | Key Finding from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| [5,6,19,20,27] | Economic and Financial Barriers | High upfront cost, limited financial incentives, cost of battery replacement concerns, and scarce second-hand market. |

| [5,6,17,21,22,28,29,30,31,32,33] | Infrastructural and Energy Barriers | Limited charging stations, urban-centered deployment, long charging times, grid limitations, and insufficient integration of smart charging and renewable energy. |

| [21,22] | Policy and Institutional Barriers | Fragmented policies, decentralized governance, lack of centralized EV strategy, and weak incentives. |

| [16,23,24,35,37,38] | Behavioral Barriers | Consumer habits, risk perception, range anxiety, and prioritization of upfront cost over long-term savings. |

| [5,6,24,39,40] | Social Barriers | Cultural attitudes, peer influence, societal norms, environmental awareness, and perceived EV social status. |

| Barriers Theme | Survey Finding | Secondary Data |

|---|---|---|

| Financial Barriers | 70% reported high upfront cost | TCO Analysis [42]: BEVs have 55% higher lifetime cost than ICEs Household incomes distribution [43]: Median households’ income fall below thresholds required to afford EVs. |

| Infrastructural Barriers | 64% reported limited charging stations 39.1% reported interest in home charging | Homeownership rate [43]: 66.4% in urban regions; apartment living limits home charger installations. Lease rate [43]: 25.7% of household rent, making charger installation legally and logistically inconvenient. |

| Market Volume and Availability | 39.1% reported limited EV availability, and scarce second-hand market | Market Dynamics [4]: |

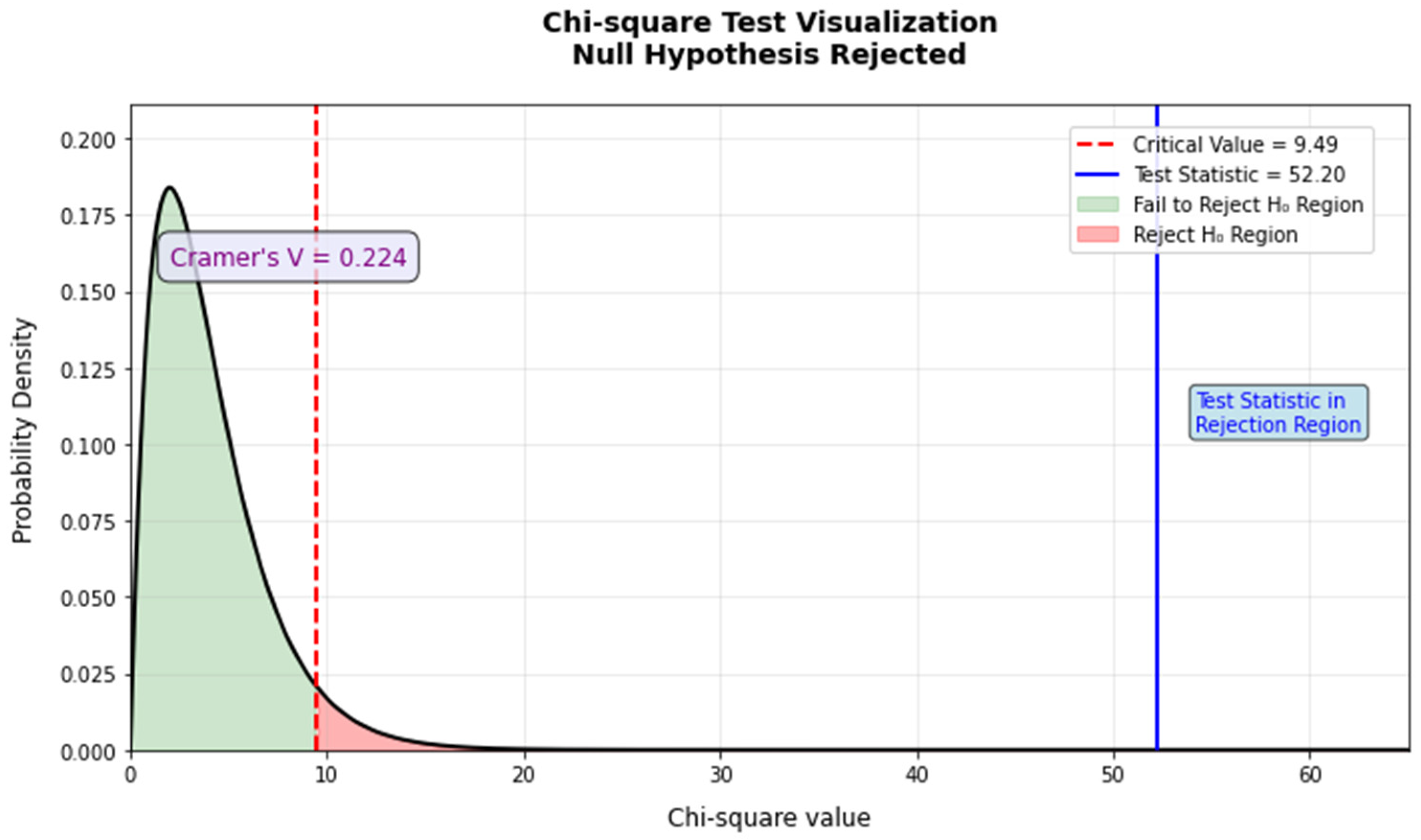

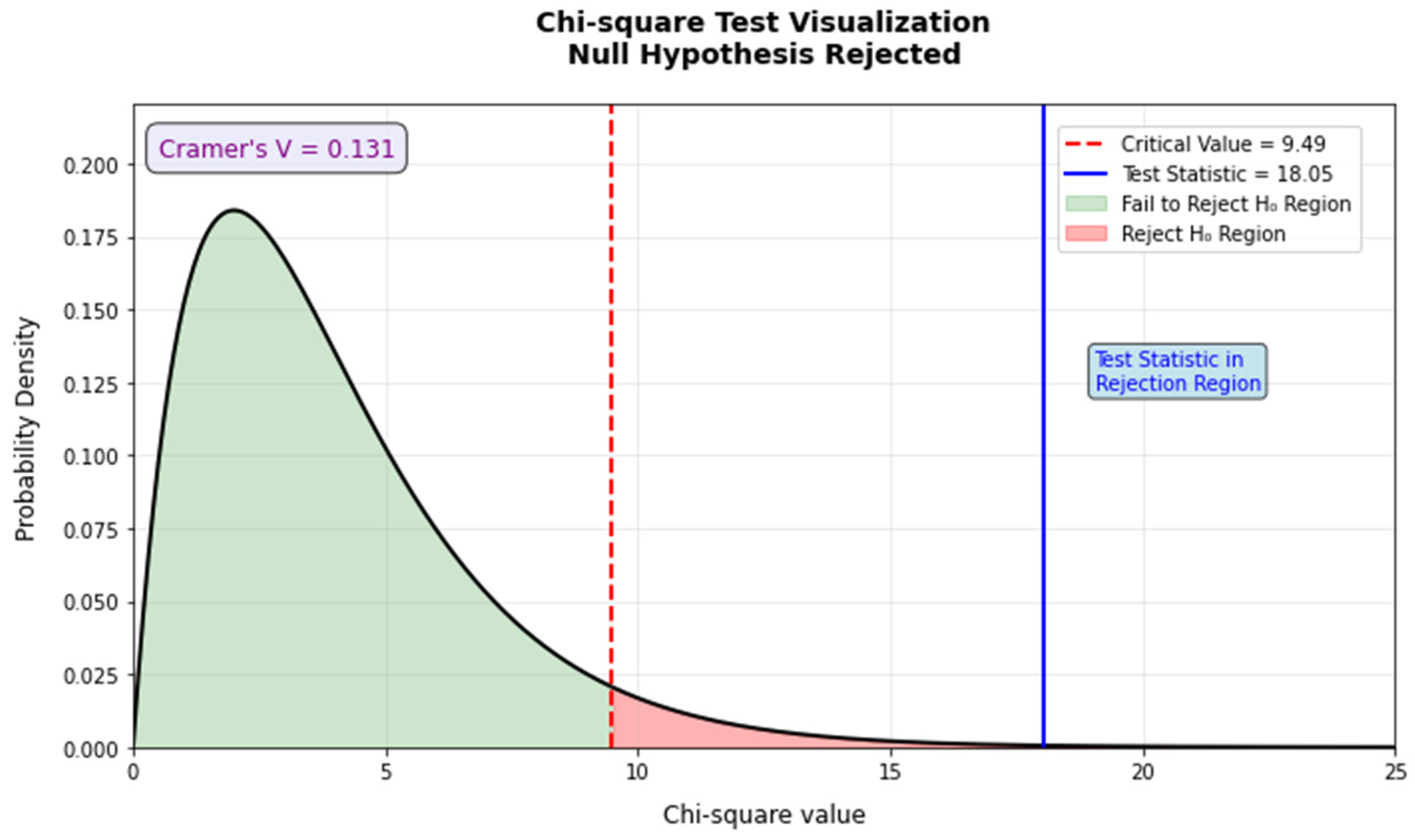

| Barriers | Low Infrastructure Concern | High infrastructure Concern | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Cost Concern | 60 | 114 | 174 |

| High-Cost Concern | 78 | 270 | 348 |

| Total | 138 | 384 | 522 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meskine, S.; El Asri, H.; Al-Majeed, S. Investigating Barriers to EV Adoption in Morocco: Insights from an Emerging Economy. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120672

Meskine S, El Asri H, Al-Majeed S. Investigating Barriers to EV Adoption in Morocco: Insights from an Emerging Economy. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):672. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120672

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeskine, Sara, Hayat El Asri, and Salah Al-Majeed. 2025. "Investigating Barriers to EV Adoption in Morocco: Insights from an Emerging Economy" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120672

APA StyleMeskine, S., El Asri, H., & Al-Majeed, S. (2025). Investigating Barriers to EV Adoption in Morocco: Insights from an Emerging Economy. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 672. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120672